1. Context

Type 1 diabetes mellitus (T1DM) is a chronic autoimmune disease predominantly diagnosed in childhood or adolescence, and it requires daily and precise management. This condition relies on insulin to control blood glucose levels, which creates various challenges for both patients and their families. Globally, the incidence of type 1 diabetes among children and adolescents is increasing by approximately 3 - 4% annually, with over 1.2 million individuals under the age of 20 currently living with the disease (1, 2). Poorly controlled T1DM in this age group is associated with serious complications such as diabetic ketoacidosis, growth retardation, cognitive impairment, reduced school performance, and long-term risks like retinopathy, nephropathy, and cardiovascular diseases (3, 4).

Since T1DM can lead to both physical and psychological complications in children and adolescents, effective self-management is crucial for maintaining control of the disease (5). Self-management includes regular glucose monitoring, insulin administration, following a specific diet, and engaging in physical activity, all of which are governed by national treatment guidelines such as those from the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) (6). However, managing the disease in children and adolescents can be particularly challenging due to the need for additional social, psychological, and educational support.

Identifying barriers and facilitators to self-management in children and adolescents with T1DM is of significant importance. Various barriers, such as insufficient awareness, psychological issues, social pressures, and lack of family and educational support, can disrupt the self-management process. On the other hand, facilitators such as effective education, family support, and the use of modern technologies can aid in overcoming these barriers and improving self-management (7).

2. Objectives

The aim of this systematic review is to evaluate interventional studies on children and adolescents with type 1 diabetes, comparing self-management interventions with standard care, to identify and synthesize the facilitators and barriers of self-management and their impact on health outcomes.

3. Methods

3.1. Reporting Guidelines

This systematic review was conducted following the preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses (PRISMA) 2020 guidelines (8).

3.2. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

3.2.1. Eligibility Criteria

Studies were included if they met the following criteria:

- Participants: Children and adolescents with T1DM, aged 3 - 19 years, or studies referring to the target population as "children" or "pediatric".

- Interventions: Behavioral interventions aimed at improving self-care, including self-monitoring of blood glucose, insulin administration, physical activity, dietary management, psychological support, or metabolic outcomes such as hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c).

- Comparators: Presence of a control or comparator group was not mandatory.

- Outcomes: Changes in self-care behaviors, psychosocial factors, and clinical outcomes such as HbA1c.

- Study Design: Interventional studies including randomized controlled trials (RCTs), cluster RCTs, crossover RCTs, prospective interventional studies, pilot studies, and quasi-experimental studies.

3.2.2. Exclusion Criteria

Studies were excluded if they: (1) Were observational (cross-sectional, cohort, case-control) or qualitative; (2) were narrative reviews, previous systematic reviews, meta-analyses, protocols, theoretical articles, letters, or editorials; (3) focused solely on digital tools without accompanying behavioral interventions; (4) targeted type 2 or gestational diabetes, or adult populations; (4) evaluated only pharmacological treatments without behavioral or educational interventions.

In cases of ambiguity regarding study design, final decisions were made by consensus between two independent reviewers.

3.3. Search Strategy

A comprehensive literature search was conducted across twelve international electronic databases, including PubMed, Scopus, and Web of Science, from inception to August 10, 2025. Keywords and Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) terms related to self-care, self-management, type 1 diabetes, children, and adolescents were combined using Boolean operators (AND, OR). No language restrictions were applied, and only studies with full-text availability were included. Filters were applied to select interventional study designs, including RCTs, quasi-experimental, and controlled clinical trials. The initial number of records retrieved from each database is summarized in Table 1.

| Database | Search Terms (Keywords+Boolean Operators) | Filters Applied | Initial Results (Number) |

|---|---|---|---|

| PubMed | ((“Diabetes Mellitus” [Mesh terms] OR “Type 1 Diabetes” [Title/Abstract] OR “Insulin-Dependent Diabetes Mellitus” [Title/Abstract] OR “Insulin Dependent Diabetes Mellitus” [Title/Abstract] OR “Type 1 Diabetes Mellitus” [Title/Abstract] OR “Juvenile-Onset Diabetes Mellitus” [Title/Abstract] OR “IDDM” [Title/Abstract] OR “Juvenile Onset Diabetes” [Title/Abstract] OR “Autoimmune Diabetes” [Title/Abstract] OR “Ketosis-Prone Diabetes Mellitus” [Title/Abstract]) AND (“self-care” [Mesh terms] OR “self-care” [Title/Abstract] OR “self -management” [Mesh terms] OR “self-management” [Title/Abstract] OR “self-management” [Title/Abstract]) AND (“Child” [Mesh terms] OR “children” [Title/Abstract]) AND (“Adolescent” [Mesh terms] OR “Adolescent” [Title/Abstract] “Adolescence” [Title/Abstract] OR “Female Adolescent” [Title/Abstract] OR “Female- Adolescent” [Title/Abstract] OR “Male Adolescent” [Title/Abstract] OR “Male- Adolescent” [Title/Abstract] OR “Youth” [Title/Abstract] OR “Teen” [Title/Abstract] OR “Teenager” [Title/Abstract])) | - | 560 |

| Scopus | (( TITLE-ABS-KEY ( "Diabetes Mellitus" ) OR TITLE-ABS-KEY ( "Type 1 Diabetes" ) OR TITLE-ABS-KEY ( "Insulin-Dependent Diabetes Mellitus" ) OR TITLE-ABS-KEY ( "Insulin Dependent Diabetes Mellitus" ) OR TITLE-ABS-KEY ( "Type 1 Diabetes Mellitus" ) OR TITLE-ABS-KEY ( "Juvenile-Onset Diabetes Mellitus" ) OR TITLE-ABS-KEY ( "IDDM" ) OR TITLE-ABS-KEY ( "Juvenile Onset Diabetes" ) OR TITLE-ABS-KEY ( "Autoimmune Diabetes" ) OR TITLE-ABS-KEY ( "Ketosis-Prone Diabetes Mellitus" ) AND TITLE-ABS-KEY ( "self-care" ) OR TITLE-ABS-KEY ( "self-care" ) OR TITLE-ABS-KEY ( "self-management" ) OR TITLE-ABS-KEY ( "self-management" ) AND TITLE-ABS-KEY ( "Child " ) OR TITLE-ABS-KEY ( "Children " ) AND TITLE-ABS-KEY ( "Adolescent" ) OR TITLE-ABS-KEY ( "Adolescence" ) OR TITLE-ABS-KEY ( "Female Adolescent" ) OR TITLE-ABS-KEY ( "Female- Adolescent" ) OR TITLE-ABS-KEY ( "Male Adolescent" ) OR TITLE-ABS-KEY ( "Male- Adolescent" ) OR TITLE-ABS-KEY ( "Youth" ) OR TITLE-ABS-KEY ( "Teen" ) OR TITLE-ABS-KEY ( "Teenager" ))) | - | 1461 |

| Web of Science | ((TS=("Diabetes Mellitus") OR TS=("Type 1 Diabetes") OR TS=("Insulin-Dependent Diabetes Mellitus") OR TS=("Insulin Dependent Diabetes Mellitus") OR TS=("Type 1 Diabetes Mellitus") OR TS=("Juvenile-Onset Diabetes Mellitus") OR TS=("IDDM") OR TS=("Juvenile Onset diabetes") OR TS=("Autoimmune Diabetes") OR TS=("Ketosis-Prone Diabetes Mellitus")) AND (TS=("self-care") OR TS=("self-care") OR TS=("self-management") OR TS=("self-management")) AND (TS=("Child") OR TS=("Children")) AND (TS=("Adolescent") OR TS=("Adolescence") OR TS=("Female Adolescent") OR TS=("Female-Adolescent") OR TS=("Male Adolescent") OR TS=("Male-Adolescent") OR TS=("Youth") OR TS=("Teen") OR TS=("Teenager"))) | - | 863 |

Abbreviation: MeSHs, Medical Subject Headings.

3.4. Screening Process

The screening process included:

- Initial screening based on article titles, conducted by A. R., A. S., and H. A.

- Removal of duplicates, performed by A. R., A. S., and H. A.

- Abstract screening performed independently by A. R. and E. L. M., with disagreements resolved through discussion or by consulting a third reviewer (A. S.) when necessary.

- Full-text screening conducted independently by A. R. and E. L. M., with disagreements resolved through discussion or by consulting a third reviewer (A. S.)

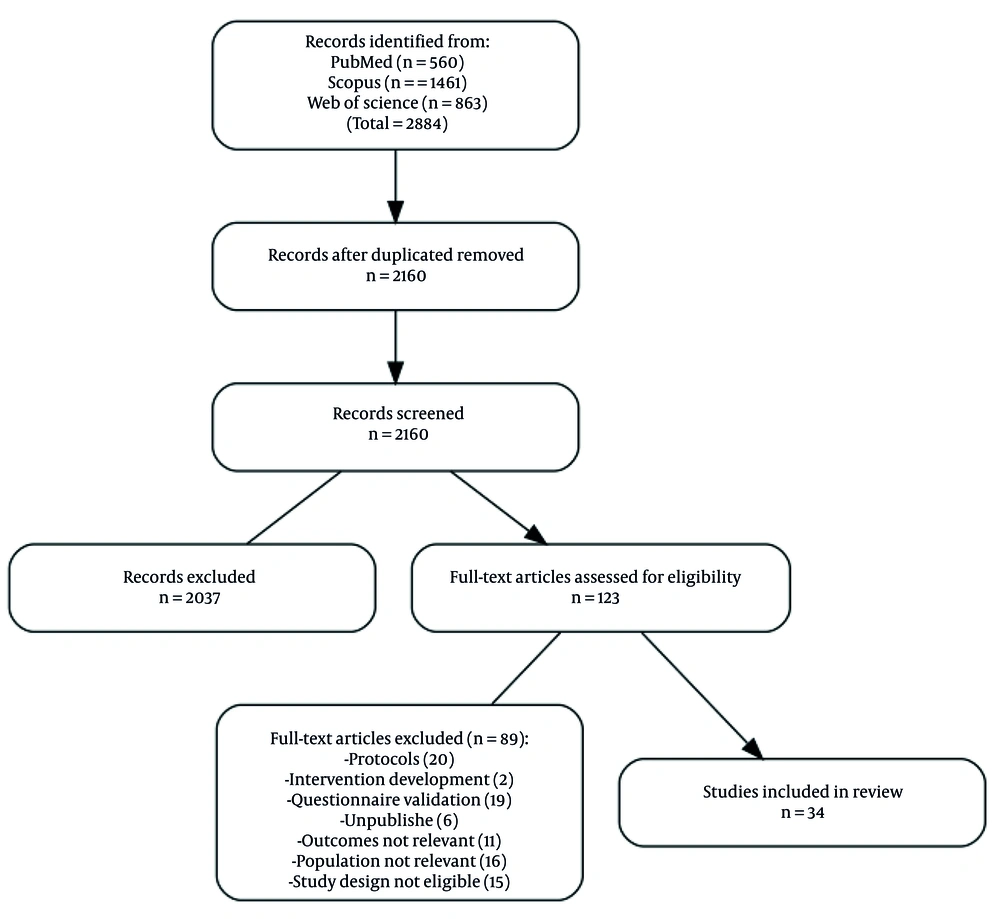

The initial agreement rate between the two reviewers was 76%, as measured by Cohen’s Kappa coefficient, which increased to 100% after discussion and clarification of the inclusion criteria (Figure 1).

3.5. Data Extraction and Quality Assessment

Data extraction was performed independently by two reviewers (A. R. and E. L. M.) using a standardized form. Disagreements were resolved through discussion or adjudicated by a third reviewer (H. A.) Extracted information included the first author’s name, year of publication, study design, age range of participants, sample size, type of self-care intervention, presence of a control group, reported facilitators and barriers, and measured outcomes. In cases of missing or unclear data, study authors were contacted for clarification.

3.6. Outcome Measurement

Given the focus of the review on identifying barriers and facilitators of self-care behaviors in children and adolescents with type 1 diabetes, the findings were synthesized descriptively based on the qualitative data reported in the included studies (Table 2). A meta-analysis was not conducted due to insufficient quantitative data and considerable heterogeneity in study designs and outcome reporting, consistent with PRISMA 2020 guidelines.

| Authors, y | Study Design | Age Range (y) | N | Type of Self-care Intervention | Control Group | Reported Facilitators | Reported Barriers | Measured Outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gunes Kaya et al., 2025 (9) | Prospective quantitative study | 8 - 18 | 47 | Recurrent individualized diabetes self-management education (insulin therapy, carbohydrate counting, blood glucose monitoring, hypoglycemia management) | - | Continuity of educational content, use of standardized module, repeated educational sessions, trained nurses and dietitians | Not reported | Hypoglycemia self-treatment, hypoglycemia awareness, TIR, GV, (FOH) |

| Sarteau et al., 2025 (10) | Pilot RCT | 13 - 16 | 44 | MyPlan: Individualized eating strategy focusing on meal timing, frequency, and carbohydrate distribution; dietitian counseling sessions | - | Counseling sessions by dietitian, food logging, family support | No reported | HbA1c, dietary goals |

| Jacobson Vann et al., 2025 (11) | Pilot RCT | 8 - 17 | 12 | Nurse-led care management: Telehealth visits, emails, MyChart messages; Motivational interviewing and unconditional positive regard | - | Low-cost and effective interventions in pediatric and adolescent populations | No reported | HbA1c |

| Sigley et al., 2025 (12) | Mixed-methods pre-post | 7 - 13 | 27 | Three-day diabetes camp with education on carbohydrate counting, insulin adjustment, injection technique, CGM use, hypoglycemia/hyperglycemia management, physical activity | - | Experienced healthcare staff and youth leaders, structured hands-on activities, supportive environment | Non-English speaking, severe developmental disorders, serious ongoing mental health disorders | Self-care behaviors, self-efficacy, quality of life |

| Malik et al., 2024 (13) | Crossover RCT | 12 - 18 | 39 | Financial incentives (up to $180 per 12-week period for achieving self-care goals | Usual care | Reduced impact of financial incentives after program completion | Financial incentives), personal choice of treatment goals | SMOD-A, TIR, HbA1c |

| Pabedinskas et al., 2023 (14) | Longitudinal educational program | 13 - 17 | 232 (phase 1) 215 (phase 2) 91 (phase 3) | Self-care skills education (blood glucose control, insulin dose adjustment, physical activity, and diet management) | - | Low confidence in basic skills (e.g., ketone management, insulin dose adjustment) | Increased self-confidence in self-care skills, structured and repetitive education, availability of diabetes consultants | SMOD-A, HbA1c |

| Zarifsaniey et al., 2022 (15) | Pilot RCT | 12 - 18 | 66 | Self-care education through digital storytelling and telephone follow-up | Usual care | Engagement with the story, motivational messages, telephone follow-up, combination of formal and digital education | Time constraints, lack of real-time interaction with healthcare providers, motivational challenges | SMOD-A, HbA1c |

| Temmen et al., 2022 (16) | RCT | 9 - 15 | 390 | Parental involvement in daily diabetes tasks, problem-solving, planning, and emotional support | Usual care | Collaborative parental involvement, low level of parent-adolescent conflict, emotional support | High conflict between parents and adolescents, low parental involvement in diabetes management | HbA1c, Peds QL, CDI, DSMP, parent-child conflict |

| Al Ksir et al., 2022 (17) | RCT | 13 - 16 | 66 | Education on general and disease-specific self-management skills (e.g., blood sugar management, insulin usage) | Usual care | Motivational interviewing, nursing support, continuous communication with the healthcare team | No specific barriers mentioned in the article | HbA1C, TRAQ |

| Lertbannaphong et al., 2021 (18) | RCT | 10 - 18 | 35 | Receiving self-management education sessions combined with motivational interviewing | Usual care | Family support, psychological counseling, motivation enhancement through MI | Motivational challenges and limited self-care knowledge/skills | Knowledge, self-care |

| La Banca et al., 2021 (19) | Pilot RCT | 7 - 12 | 20 | Insulin injection technique education using play therapy intervention | Usual care | Interactive education, parental involvement, use of storytelling for better understanding by children | No change in insulin injection levels after 30 days, challenges in changing children's behavioral habits | Insulin injection technique and self-injection of insulin |

| Kichler and Kaugars 2021 (20) | Semi-structured group Intervention | 10 - 17 | 20 | Parental and adolescent participation in multi-family group therapy for diabetes management | - | Peer support, family interaction, focus on behavior change and problem-solving skills | High dropout rate, differences in parental participation, challenges in transferring responsibility to adolescents | SMOD-A, HbA1c |

| McGill et al., 2020 (21) | RCT | 13 - 17 | 301 | BG monitoring and bolus insulin dose adjustment | Usual care | Receiving regular SMS messages and responding to them enhances adolescents' engagement with diabetes management | Lack of response from some participants to SMS messages and the need for long-term engagement | BG monitoring, SMOD-A HbA1c |

| Wagner et al., 2019 (22) | RCT | 10 - 19 | 60 | SMBG with adherence to recommended testing frequency | Usual care | Financial rewards for regular monitoring, reminder SMS for blood glucose checks, and use of automatic upload systems for glucose management | Need for internet access and digital devices; Potential drop in motivation after financial rewards are discontinued | HbA1c, SMBG |

| Pramanik et al., 2019 (23) | Self-controlled case series SCCS | 11 - 18 | 28 | Mobile reminders for insulin injections, meals, and physical activity management | - | Scheduled reminders, no need for internet access, ability to record blood glucose levels | Lack of access to a smartphone, technical issues with the app’s functionality | HbA1c |

| Fiallo-Scharer et al., 2019 (24) | RCT | 8 - 16 | 214 | Blood glucose control, adherence to diet, family involvement, and self-management motivation | Usual care | Family support, increased motivation, personalized educational resources, positive family interactions | Lack of motivation, difficulties in understanding and organizing care, negative family interactions | QOL, HbA1c |

| Emiliana et al., 2019 (25) | Quasi-experimental | 6 - 18 | 31 | Diet management, physical activity, treatment, stress management, and blood glucose control | - | Family support, access to quality education, use of multimedia educational content (animated videos) | Economic challenges, lack of family support, limited access to blood glucose test strips, insufficient insulin dosage through national insurance | Self-management, family support and adherence level |

| Doger et al., 2019 (26) | Quasi-experimental (single group pretest-posttest) | 2 - 18 | 82 | Counseling and follow-up through a telehealth system, including phone calls, SMS, and WhatsApp | - | Continuous communication with the diabetes team, quicker access to treatment guidance, reduced need for in-person visits | Lack of 24-hour system coverage, time limitations for contacting the medical team | HbA1c, self-management, DKA |

| Chatzakis et al., 2019 (27) | RCT | 7 - 17 | 80 | Insulin management, glucose control, carbohydrate and lipid counting, insulin dose adjustment based on an app | Usual care | Use of an app to simplify insulin calculations, quick access to nutritional information, and patient education and awareness about blood glucose control | Need for an Android smartphone, skill in using the app, and adapting personal settings to individual needs | HbA1c, hypoglycemia, hyperglycemia, treatment satisfaction (DTS) |

| Brorsson et al., 2019 (28) | RCT | 12 - 18 | 71 | The GSD-Y model (guided self-determination-Young), an individual-centered educational approach based on communication and reflection | Usual care | Group education and the GSD-Y model, parental involvement in the learning process, and structured intervention sessions | Family conflicts and differences in the effectiveness of education between girls and boys | HbA1c, QOL, family conflicts, self-efficacy, self-perceived health |

| Stanger et al., 2018 (29) | RCT | 13 - 17 | 61 | Self-monitoring of blood glucose levels, parental supervision of diabetes management, and working memory exercises | Usual care | Regular reminders for blood glucose monitoring, parent education for supervising diabetes management, financial incentives for encouraging self-management, and working memory exercises to improve executive skills | Limited access to high-speed internet for some families, technical issues with the app, family conflicts over diabetes management, and non-adherence of some adolescents to blood glucose monitoring | HbA1c, SMBG, family conflicts |

| Klee et al., 2018 (30) | Randomized double-crossover study | 10 - 18 | 55 | Diabetes management through a mobile app, including blood glucose monitoring, monthly feedback, and treatment adjustments | Usual care | Use of a simple mobile app designed by patients, monthly feedback and treatment adjustments, and good acceptance of the program by users | Insufficient use of the app | HbA1c, QOL, hypoglycemia, |

| Cai et al., 2017 (31) | Pilot RCT | 8 - 16 | 22 | Workshop on glucose control, HbA1c outcomes, managing hypo/hyperglycemia, self-management skills, and diabetes communication | - | Family involvement, peer groups, and experience sharing. | Low family participation | HbA1c, QOL, FOH |

| Joubert et al., 2016 (32) | Pilot multicenter RCT | 11 - 18 | 38 | Flexible insulin therapy, carbohydrate counting, and insulin dose adjustment | Usual care | Problem-based learning, simulated scenarios, interaction with the digital environment | Low engagement in play by some children, limited interaction with the medical team | HbA1c, DSMP |

| Price et al., 2013 (33) | Cluster-RCT | 11 - 16 | 560 | Structured education program (insulin management, blood glucose control, nutrition, and social conditions) | Usual care | Parental involvement, group-based education, online support, and workshop sessions | Challenges in maintaining adolescent motivation, potential changes in insulin regimen to a pump, which may affect outcomes | HbA1c, QOL, DKA, hypoglycemia |

| Santiprabhob et al., 2012 (34) | Prospective interventional study | 12 - 18 | 27 | Diabetes self-care education (insulin management, nutrition, blood glucose control, and addressing disease-related issues) | - | Interactive education, psychosocial support, and follow-up sessions after the camp | Difficulty adhering to the diet, inability to maintain intervention effects in the long term | Knowledge, DSMB HbA1c, QOL |

| Robling et al., 2012 (35) | RCT | 4 - 16 | 693 | Participation in counseling sessions with the pediatric diabetes team to improve self-management skills | Usual care | Team meetings, guiding communication style, and setting a shared agenda | Team meetings, guiding communication style, and setting a shared agenda | HbA1c, QOL DSMB |

| Mulvaney et al., 2010 (36) | RCT | 13 - 17 | 72 | Use of an online program to improve problem-solving skills and diabetes management | Usual care | Peer interaction, sending motivational emails, availability of problem-solving solutions | Need for internet access, variable adolescent participation in program activities | HbA1c, DSMB |

| Franklin et al., 2005 (37) | Educational intervention study | 7 - 19 | 11 | Use of the Librae digital simulator to predict the effects of dietary, activity, and insulin regimen changes on blood glucose levels | - | Learning through digital simulation, the ability to experience treatment changes without real risk, continuous glucose monitoring | Modeling errors at high blood glucose levels, time-consuming data entry, challenges in accurately recording dietary intake | Diabetes self-care skills |

| Franklin et al., 2006 (38) | RCT | 8 - 18 | 126 | Receiving personalized supportive text messages to remind self-management goals | Usual care | Personalization of messages, tailored based on age, gender, and insulin regimen, motivation enhancement | Some adolescents were dissatisfied with receiving repetitive messages, need for constant reminders | Self-efficacy, treatment adherence |

| Schiel et al., 2005 (39) | RCT | 9 - 18 | 551 | Blood glucose management, insulin adjustment, hypoglycemia detection and management, increasing diabetes awareness | Usual care | Parental support, continuous education, structured follow-ups, psychological involvement | Long intervals between educational sessions, motivational challenges in some patients | HbA1c, knowledge, QOL, DSMB, hypoglycemia |

| Wysocki et al., 2003 (40) | RCT | 6 - 16 | 142 | Self-management competence includes diabetes knowledge, treatment adherence, and the quality of interactions with the healthcare team. | Usual care | Knowledge, treatment adherence quality of physician interactions | Lack of sufficient diabetes knowledge, Poor treatment adherence, Inadequate interactions with the healthcare team, Socioeconomic status | HbA1c, knowledge, treatment adherence (SMC) |

| Delamater et al., 1990 (41) | RCT | 3 - 16 | 36 | Using blood glucose monitoring data for daily diabetes management | Usual care | Continuous education by the healthcare team, use of glucose monitoring for decision-making in diet and exercise | Motivational challenges, treatment adherence issues, need for continuous support | HbA1c, DSMB, hypoglycemia |

| Kohler et al., 1982 (42) | Educational intervention study | 5 - 16 | 209 | Gradual education of self-care skills including insulin injection, glucose monitoring, and dietary management | - | Multidisciplinary team including physicians, nurses, dietitians, and social workers | Decreased motivation in adolescents, reduced willingness to self-monitor at older ages | DSMB |

Abbreviations: TIR, time in range; GV, glycemic variability; FOH, fear of hypoglycemia; HbA1c, hemoglobin A1c; BG, blood glucose; SMBG, self-monitoring of blood glucose; QOL, quality of life.

3.7. Risk of Bias Assessment

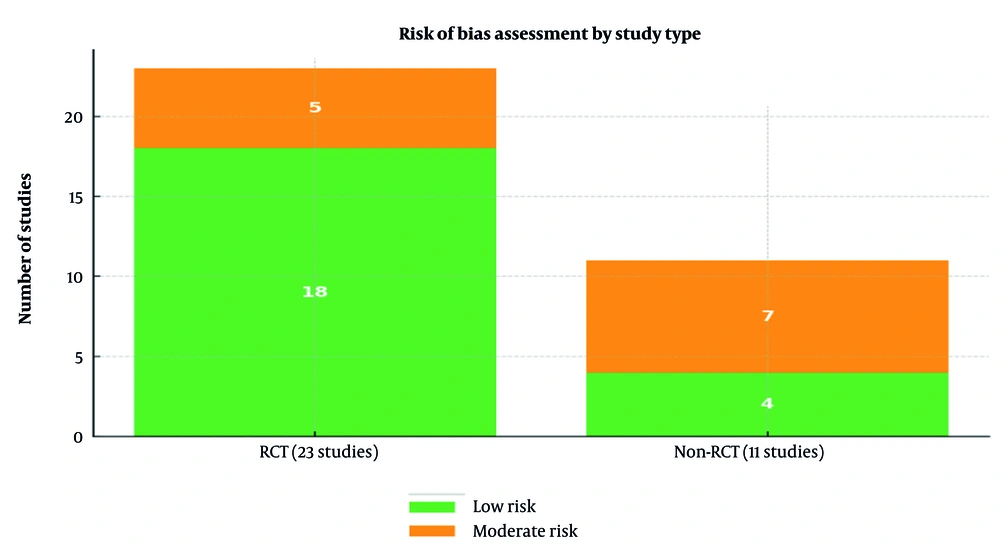

The quality and risk of bias of the included studies were systematically assessed according to study design. The RCTs were evaluated using the Cochrane risk of bias 2 (RoB 2) tool, which examines five key domains: The randomization process, deviations from intended interventions, missing outcome data, measurement of outcomes, and selection of reported results. Each domain was rated as low risk, some concerns, or high risk.

Non-randomized studies (non-RCTs) were assessed using the Risk of Bias in non-RCTs of interventions (ROBINS-I) tool, which considers seven domains, including confounding, participant selection, intervention classification, deviations from intended interventions, missing data, outcome measurement, and selective reporting. Domains were rated as low, moderate, serious, or critical risk. A comprehensive evaluation was performed for all included studies to ensure an accurate assessment of evidence quality and to support the interpretation of the findings.

4. Results

4.1. Characteristics of Included Studies

A total of 34 interventional studies met the inclusion criteria and were included in this systematic review. Most interventions were conducted in the adolescent age group (13 - 17 years) and in combined age groups of 8 - 18 years. Six studies (17.6%) focused specifically on adolescents aged 13 - 17 years (14, 17, 20, 21, 29, 36), and ten studies (29.4%) targeted combined age groups of 8 - 18 years (9, 11, 13, 15, 18, 25, 26, 30, 38, 40). Fewer studies were conducted in younger children (6 - 12 years) or broader age ranges (12, 19). All included studies met the inclusion criteria of 5 - 19 years (Table 2).

4.2. Risk of Bias Assessment

A quality assessment was conducted for the 34 included interventional studies. Among the 23 RCTs, 18 studies were rated as having a low risk of bias, and 5 as moderate risk. Among the 11 non-randomized studies, 4 were classified as low risk, and 7 as moderate risk. Overall, 22 studies (65%) were considered low risk, and 12 (35%) moderate risk; none were rated as high risk (Figure 2).

Regarding specific domains, in RCTs, approximately 65% had issues related to blinding, 50% reported incomplete outcome data, and 10% showed selective outcome reporting. In non-randomized studies, 55% had moderate risk due to confounding, and 40% due to participant selection. These findings indicate that the majority of included studies were of acceptable quality, supporting the reliability of the synthesized evidence (Figure 2).

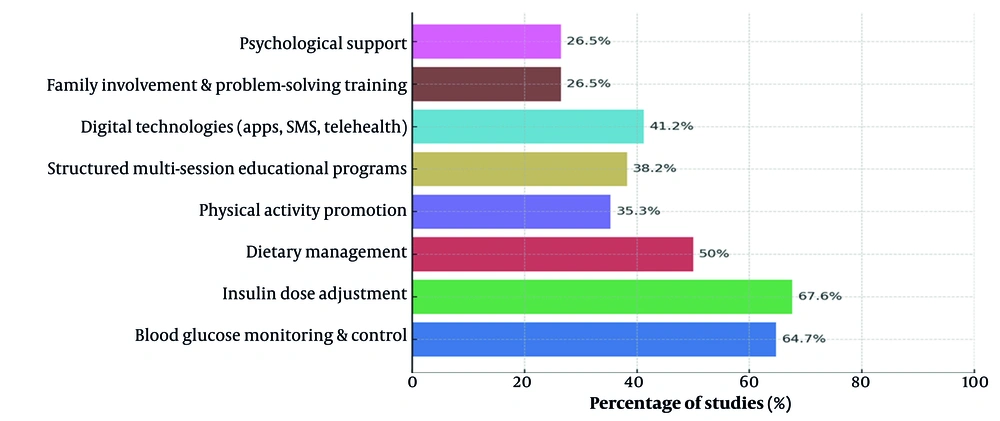

4.3. Types of Self-management Interventions

In the self-management interventions reviewed across 34 studies, the content of self-care education was highly diverse. As shown in Figure 3, the main components of self-management interventions and their frequency across studies are summarized. Some common components included blood glucose monitoring and control, which was reported in most studies (64.7% of studies) (9-24, 26, 28-32). Insulin dose adjustment was addressed in approximately 67.6% of studies (9, 11, 13-17, 22-29, 31-36, 38, 39). Dietary management was included in about 50% of studies (10, 13, 14, 16, 17, 24-35, 39). Physical activity promotion was applied in 35.3% of studies (12-14, 16, 24, 25, 27, 30, 31, 33, 35, 36). Additionally, structured multi-session educational programs, present in approximately 38.2% of studies, were implemented in (9, 12, 14, 16, 17, 24, 25, 27, 29, 31, 33, 36, 38). The use of digital technologies, including mobile apps, text messaging, and telehealth systems, was incorporated in 41.2% of studies (13, 15, 16, 23-27, 29-32, 36). Some studies also emphasized family involvement and problem-solving skill training. Psychological support was included in approximately 26.5% of interventions to improve self-efficacy and quality of life (Figure 3) (10- 12, 14, 17, 18, 20, 25, 27, 29).

4.4. Use of Technology

Among the 34 included studies, 24 studies (70.58%) utilized some form of technology to enhance self-management, including (13, 15, 16, 21-31, 33, 35-39). The most commonly used technologies included continuous glucose monitoring devices, which were used in 20.58% of the studies, such as (12, 13, 16, 22, 26, 27, 29); mobile applications, noted in 16.6% of the studies, including (15, 23, 27, 30, 35); and reminder text messages, also utilized in 16.6% of the studies, such as (21, 22, 36, 38). In contrast, 10 studies (29.41%) (9-11, 14, 17, 18, 19, 25, 31, 34) did not use any specific technology and relied solely on traditional face-to-face methods for education delivery.

4.5. Facilitators of Self-management

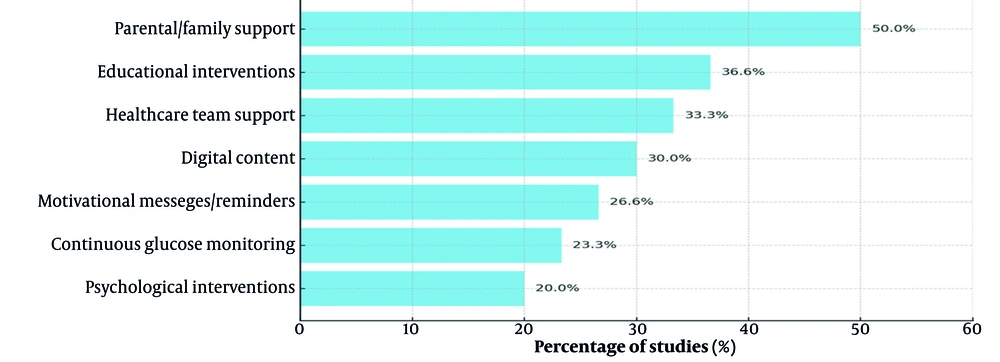

As shown in Figure 4, several key facilitators of self-management were identified across the included studies. Parental and family support emerged as the most frequently reported facilitator, found in approximately 50% of the studies, such as (10, 13, 16, 20, 24, 25, 27, 28, 29, 31-33, 35, 39). Interactive and structured educational interventions were highlighted in 36.6% of the studies, including (9 ,12, 14, 17, 24, 25, 27, 29, 31, 33, 35, 37). Support provided by the healthcare team was identified as a facilitator in 33.3% of the studies, such as (11 ,14, 17, 24, 25, 27, 29, 31, 33, 35). The use of digital content, including mobile applications, online platforms, and telehealth, was noted in 30% of the studies, including (11, 15, 21, 23, 26, 27, 29, 30, 35). Motivational messages and reminders contributed to improved self-management in 26.6% of the studies, such as (21, 22, 36, 38). Continuous glucose monitoring was identified as a facilitating factor in 23.3% of the studies, including (9, 12, 13, 16, 22, 26, 29). Finally, psychological interventions, particularly motivational interviewing, were effective facilitators in 20% of the studies, such as (11, 17, 18, 27, 29, 31).

4.6. Barriers to Self-management

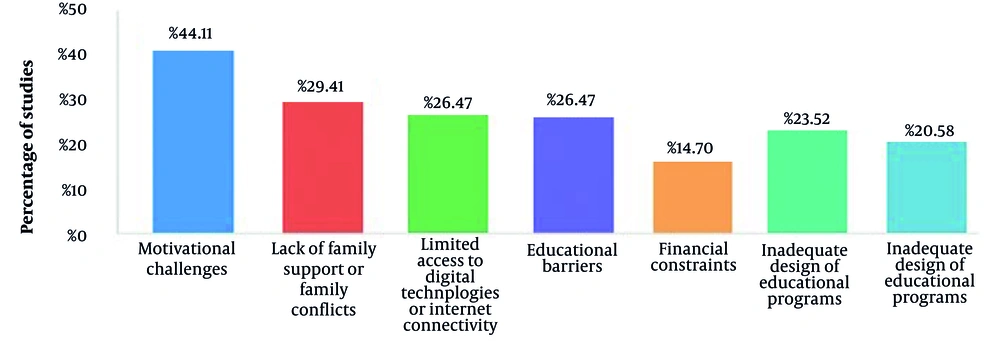

The most commonly reported barriers to effective self-management included motivational challenges, observed in 44.11% of the studies, such as (9-12, 15, 16, 20, 24, 25, 27, 29, 31, 33, 35, 36). Lack of family support or family conflicts was noted in 29.41% of the studies, including (10, 12, 16, 20, 24, 28, 29, 31, 33, 35). Limited access to digital technologies or internet connectivity was identified in 26.47% of the studies, such as (9, 11, 15, 23, 26, 27, 30, 35, 36). Educational barriers, including low knowledge or poor understanding of self-care, were mentioned in 26.47% of the studies, like (9, 10, 12, 14, 17, 24, 25, 27, 29). Financial constraints were found in 14.70% of the studies, including (13, 22, 25, 27, 30), and poor communication with the healthcare team was reported in 23.52% of the studies, such as (9-11, 14, 17, 24, 25, 31). Finally, inadequate design of educational programs was identified in 20.58% of the studies, including (Figure 5) (9, 12, 14, 25, 31, 35, 37).

4.7. Primary Health Outcomes

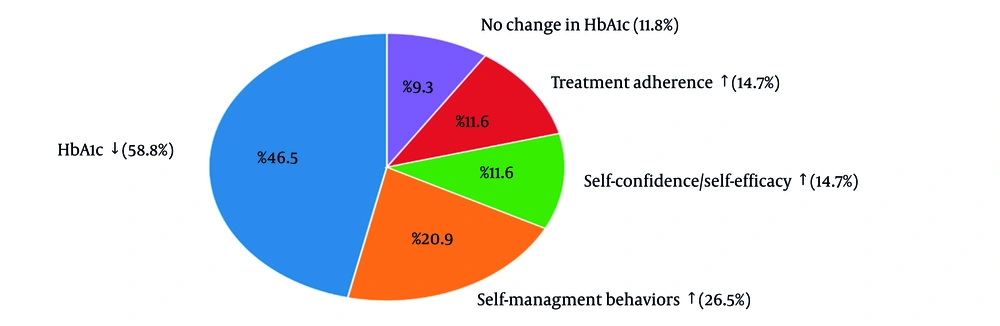

As illustrated in Figure 6, the most frequently reported primary outcome was a significant reduction in HbA1c, observed in 58.8% of studies (13-17, 24, 21-23 , 26-30, 32-35). Improvements in self-management behaviors were reported in 26.5% (14, 16, 20, 24, 25, 27, 29, 31, 33), while increased self-confidence and self-efficacy, as well as enhanced treatment adherence, were each reported in 14.7% (14, 16, 20, 21, 25, 27, 29, 35). Additional primary outcomes included better hypoglycemia self-management, greater hypoglycemia awareness, improved time in range (TIR) and glycemic variability (GV), and reduced fear of hypoglycemia (FOH) (9). Nevertheless, 11.8% of studies reported no significant change in HbA1c (Figure 6) (15, 26, 35, 37).

4.8. Secondary Health Outcomes

Secondary outcomes focused on broader behavioral, psychosocial, and educational effects. Improvements in quality of life were reported in 29.4% of studies (13, 14, 16, 24, 28, 9, 12, 29, 30, 33), increased diabetes knowledge in 17.6% (10, 14, 17, 24, 27, 29), reductions in hypoglycemic or hyperglycemic events and hospitalizations in 17.6% (9, 13, 27, 29, 30, 33), improvements in parent–child relationships in 14.7% (12, 16, 20, 24, 29), and increased patient satisfaction with educational programs in 14.7% (10, 17, 27, 29, 31). Additionally, some studies reported improvements in cognitive function (12) and adolescent affiliation with peer groups (12). However, in certain studies, no significant changes were observed in quality of life or diabetes management scores.

5. Discussion

This systematic review of 34 interventional studies examined self-management in children and adolescents with type 1 diabetes, focusing on key facilitators and barriers. Findings indicate that successful interventions are multidimensional, combining education, family support, digital tools, and psychological strategies, which collectively enhance self-care skills, confidence, and engagement with both family and healthcare teams (9-42).

5.1. Facilitators

Structured and repeated education, reported in 11 studies (9, 14), improved adolescents’ ability to manage hypoglycemia and adhere to dietary recommendations. Individualized programs, such as MyPlan, and nurse-led telehealth interventions (10, 11) supported personal skill development and sustained behavior. Family involvement, reported in 10 studies (16, 24), played a critical role in reducing parent–child conflict and enhancing adherence. Digital tools, including mobile applications and short message service reminders, were effective in 7 studies (11, 23, 30), promoting daily engagement. Supportive environments, such as camps and practical group activities, were reported in 5 studies (12, 20) and strengthened practical skills and peer interaction. Targeted psychological interventions, including motivational interviewing, Acceptance and Commitment Therapy, and spiritual therapy, reported in 6 studies (17, 18, 43), enhanced adherence and self-efficacy.

5.2. Barriers

Economic constraints and limited access to diabetes supplies, reported in 6 studies (13, 25), reduced adherence to blood glucose monitoring and insulin administration. Technological limitations in 5 studies (29, 30) hindered consistent application use. Family-related and motivational challenges, including low parental involvement or interest and parent-child conflict, were reported in 7 and 5 studies (12, 16, 38, 42). Environmental factors, such as exposure to organochlorine pesticides, also influenced diabetes management (44).

These findings indicate that multidimensional, developmentally tailored, family-centered interventions with digital and psychological support have the greatest potential to improve self-management behaviors. Facilitators strengthen confidence and adherence, whereas economic, technological, and family-related barriers can limit effectiveness. Addressing psychological and environmental factors is essential for sustainable and equitable support for adolescents (43, 44).

5.3. Conclusions

Self-management interventions in children and adolescents with type 1 diabetes are most effective when they target behavioral, cognitive, and psychosocial mechanisms simultaneously. Structured education, individualized nutrition plans, digital health tools, and supportive environments enhance self-efficacy, motivation, and adherence, while family and contextual factors modulate outcomes. Multifaceted, flexible, and developmentally appropriate strategies are recommended to achieve sustainable improvements, and future longitudinal studies should explore the long-term effectiveness and identify the most impactful components.

5.4. Limitations

The included studies in this systematic review have several limitations that may affect the validity and generalizability of the findings. Many studies had relatively small sample sizes, with several including fewer than 50 participants (11, 19, 20, 31), which may limit statistical power and generalizability. Follow-up periods were often short, with some interventions lasting only a few weeks or months (12, 19, 37), restricting the assessment of long-term sustainability of improvements in self-care behaviors and glycemic outcomes.

A substantial proportion of studies relied on self-reported measures of adherence, self-efficacy, or quality of life (10, 14, 25), which may be subject to reporting or social desirability bias. Variability in intervention content, delivery methods, and outcome measures across studies limits direct comparability and contributes to heterogeneity in reported effects. Some studies used digital technologies, such as mobile applications or telehealth (13, 15, 16, 21-23), whereas others relied solely on traditional face-to-face education (9, 11, 14, 17, 18), making it difficult to isolate the specific impact of technological components.

Although the overall risk of bias was low to moderate, incomplete outcome data (50% of studies) and limited blinding in RCTs (65% of trials) may affect internal validity. Contextual factors, including socioeconomic status, family support, and healthcare system differences, were not consistently controlled, potentially influencing intervention effectiveness and limiting generalizability.

Considering these limitations, while the reviewed interventions show promising effects on self-care, glycemic control, and psychosocial outcomes in children and adolescents with type 1 diabetes, larger, longer-term, and methodologically rigorous studies are needed to confirm and extend these findings.