1. Context

Cancer remains a significant global public health issue, with its incidence steadily increasing (1). Patients with cancer, particularly in advanced stages, commonly face complex, persistent, and multidimensional symptoms that adversely affect their quality of life (QoL) (2, 3). Palliative care (PC), as a holistic and interdisciplinary approach, aims to alleviate suffering in individuals with chronic, progressive, or terminal illnesses (4, 5). According to the World Health Organization, PC enhances QoL by addressing physical, psychological, social, and spiritual problems through early identification and comprehensive management (6). In oncology nursing, PC has become an integral part of symptom management throughout the disease course (7, 8). The main goals of PC include improving QoL, reducing symptom burden, and reducing hospital utilization and healthcare costs, while providing support to both patients and families (9).

Nurses play a critical role in the delivery of palliative care. They provide not only symptom management but also communication, emotional support, and coordination across multidisciplinary teams for more effective care (10, 11). Despite their essential role, limited access to PC services persists in many countries (12, 13). Consequently, oncology nurses must be adequately equipped to address evolving cancer care needs (7).

Despite the multidimensional role of oncology nurses in PC, there is a significant knowledge gap regarding their specific contributions, challenges, and educational needs in Iran, particularly in the management of multidimensional cancer-related symptoms. This gap highlights the need for a comprehensive review to incorporate nursing perspectives and guide future PC development in Iran. The aim of this review is to provide a comprehensive view of the promotion of PC by oncology nurses for symptom management, while also identifying the current status of PC and its existing barriers in Iran.

1.1. Context of Iran

It is predicted that by 2025, the rate of cancer in Iran will exceed 130,000 new cases, which represents an increase of more than 35% compared to the current rate (14). Addressing this growing burden requires not only more resources but also a greater focus on the development of PC services. Despite this need, PC is not sufficiently integrated into the Iranian healthcare system and access to it remains limited (10, 12).

2. Evidence Acquisition

2.1. Design

This study employed a state-of-the-art (SotA) review methodology to provide a comprehensive and analytical up-to-date view of the current state of knowledge on PC in oncology nursing. Unlike systematic reviews that focus on answering specific research questions through structured data aggregation, the SotA approach critically examines the development of a field, highlights scientific advances, addresses existing challenges, and suggests future research directions, rather than simply collecting and integrating studies (15).

2.2. Search Strategy and Source Selection

This study included a review of studies published between 2014 and 2025. The last database search was conducted in June 2025. Language restrictions were limited to English and Persian studies to ensure both international and national perspectives were captured. Selected articles focused on nursing experiences, palliative care, symptom dimensions, and challenges related to PC in patients with cancer. Inclusion criteria included peer-reviewed articles, original and review studies that addressed PC for adult cancer patients. Exclusion criteria included non-peer-reviewed sources and studies that focused solely on pediatric or non-cancer populations. The screening process included an initial review of the title and abstract and then an assessment of the full text for relevance. Two reviewers independently reviewed all articles.

Databases searched included PubMed, Scopus, Web of Science, Google Scholar, SID, Magiran, and the Islamic World Science and Technology Monitoring and Citation Institute (ISC). Keywords used in the search strategy included: “Palliative care”, "Symptom management", "Cancer", "Palliative nursing", "Cancer-related symptoms", "Spiritual care", "Iran", "End-of-life care", "Oncology", and "Palliative medicine". Keyword combinations using Boolean operators (AND to limit results to articles related to nursing and PC in cancer, and OR to expand the scope to related topics such as symptom management and spiritual care) were used to search the databases comprehensively and accurately. Articles were reviewed through a conceptual, integrative, and analytical perspective and organized into thematic categories within the results section.

3. Results

This review clarifies key themes related to the roles, challenges, barriers, and opportunities of PC in oncology nursing. The results are organized into four main areas. These categories provide a comprehensive understanding of the current landscape and provide strategies for improving palliative nursing practices in the oncology setting.

3.1. The Roles of Nurses in Palliative Care

Symptom clusters are defined as the simultaneous occurrence of several related symptoms, and their management is a major challenge in the nursing care of patients with cancer (2). Oncology nurses with PC expertise are uniquely positioned to address this multidimensional burden (16). Palliative nursing, which is based on a comprehensive and patient-centered approach, includes the control of physical symptoms along with psychological, social, and spiritual support. Key nursing strategies include ongoing assessment using validated tools, prioritizing patient and family needs, individualized care planning, education about the course of the disease and coping with it, implementation of nonpharmacological interventions, and participation in multidisciplinary care planning. Therefore, symptom management remains one of the main tasks of oncology nurses in PC (13, 17).

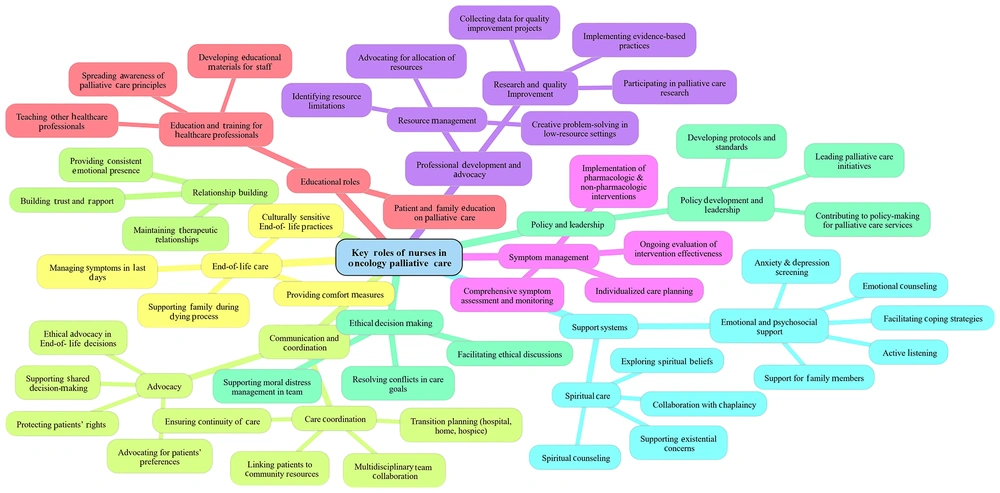

The role of nurses is critical in delivering integrated, high-quality PC that improves symptom relief, enhances QoL, and increases satisfaction among patients and families (9, 18). Oncology nurses also play a central role in educating patients and families about PC, actively engaging in care from diagnosis through end-of-life. They are often the most trusted source of information for patients, strengthening therapeutic relationships and building trust (18). Additionally, nurses contribute to care planning and ethical decision-making, particularly in complex or end-of-life scenarios, by mediating family preferences and supporting the resolution of conflicts (9, 19). Figure 1 illustrates the key roles of nurses in oncology palliative care.

3.2. Challenges Facing Nurses in Palliative Care (Focusing on Iran)

3.2.1. Educational and Training Gaps

Despite their pivotal role, nurses in oncology PC encounter numerous barriers. A major issue is the lack of specialized training. Many nurses lack competencies in complex symptom assessment, multidimensional management, and psychosocial-spiritual interventions (18). In Iran, oncology nurses rarely receive formal PC education and are often unfamiliar with essential care models such as early integration, home-based care, outpatient PC clinics, hospital PC units, multidisciplinary teams, and telemedicine (10, 14, 20). This educational gap, compounded by limited continuing professional development and inadequate PC content in nursing curricula, critically impairs care quality (21). Therefore, the lack of structured education and continuous education does not prepare nurses to provide comprehensive palliative care.

3.2.2. Nursing Shortage and Workload

Nursing shortage and high workloads further restrict holistic PC delivery (22, 23). Nursing shortages lead to time constraints, task-based care rather than comprehensive care, and reduced opportunities for psychosocial and spiritual support. Adequate nursing staffing is associated with better symptom management and improved patient outcomes (24), and this requires workforce planning at the policy level and institutional strategies to support nurses’ well-being.

3.2.3. Cultural and Ethical Barriers

Cultural sensitivities surrounding death and end-of-life care prevent patient and family engagement with PC, placing nurses in ethical dilemmas when families oppose prognosis disclosure or patient involvement in decision-making (19, 25, 26).

3.2.4. Policy and Infrastructure Limitations

Lack of infrastructure, including the absence of dedicated PC units, multidisciplinary teams, and national policies, is a challenge common in Iran and other countries, limiting effective palliative nursing (13). While Iranian nurses generally hold positive attitudes toward PC, restrictions on training, staffing, and decision-making authority curtail their full potential within PC teams (10, 20, 27, 28). There is a critical policy gap and no coherent national framework for integrating PC into oncology nursing, leading to unequal access to services and a lack of standard clinical guidelines related to PC (10, 13). Moreover, inadequate digital infrastructure and limited telemedicine implementation restrict home-based care and continuous follow-up (21). In conclusion, lack of policies, poor infrastructure, and limited digital tools restrict effective integration of PC in oncology in Iran.

3.3. Research Gaps in Palliative Care and Nursing Oncology

Despite advances in the integration of PC into oncology nursing, key research gaps remain. Most studies on the impact of interventions focus on physical symptoms, while psychological, social, and spiritual dimensions have not received as much attention as they should (29). Few studies on PC are available that are based on Iran's cultural, religious, and social contexts, and existing models are often taken from other countries without adequate adaptation (13, 21, 27). Interdisciplinary investigations, particularly involving telemedicine, artificial intelligence (AI), and machine learning in PC nursing, are rare despite their growing global relevance (30). Additionally, the management of symptom clusters remains inadequately studied in Iran, with most research addressing single symptoms rather than their complex interrelations (2, 31).

3.4. Emerging Frontiers in Oncology Palliative Care from a Nursing Perspective

3.4.1. Digital Health, Telemedicine, and Artificial Intelligence-Assisted Nursing

Recent advances in digital health, including telemedicine platforms, remote patient monitoring, and AI-based clinical decision support, offer new opportunities for oncology nurses. These technologies can improve access to PC, particularly in underserved Iranian regions, support early detection of symptom clusters, and help develop personalized care plans. Integrating such tools into nursing practice can enhance continuity of care, optimize workload distribution, and enhance evidence-based decision-making (21, 30).

3.4.2. Multidimensional Approaches: Symptom Clusters and Spiritual Care

Emphasizing symptom clusters rather than individual symptoms enables more comprehensive interventions and enhances patient QoL (2). Furthermore, spiritual care has gained increased recognition as an integral component of oncology PC programs. By integrating multidimensional symptom management with spiritual care, oncology nurses can play a key role in advancing PC delivery (32).

4. Discussion

This SotA review examined the current state of PC in symptom management from the perspective of oncology nursing, emphasizing challenges and opportunities within Iran. The findings confirm that oncology nurses’ roles extend beyond physical symptom control to include psychological, social, and spiritual care. However, substantial gaps exist between global evidence and Iran’s current PC practices. Early integration of PC into oncology nursing notably improves patient QoL (32), yet in Iran, barriers such as inadequate specialized training, nursing shortages, and cultural constraints limit nurses’ capacity to implement early PC effectively (10, 20, 23, 27).

A notable limitation in Iranian palliative oncology research is its focus on individual symptoms rather than symptom clusters and their interactions, which dominate international discourse (2). This underscores the urgent need for culturally contextualized, multidimensional research to develop PC strategies aligned with Iran’s healthcare system and sociocultural context.

Emerging technologies such as AI, telemedicine, and machine learning present significant potential to enhance PC accessibility and quality, particularly in underserved regions. Applications of AI, such as machine learning algorithms for analyzing patient-reported outcome measures (PROMs) and predicting the severity of symptom clusters, can improve early diagnosis and personalized interventions. For example, AI-based clinical decision support systems (CDSS) can analyze multidimensional patient data and provide nurses with evidence-based treatment recommendations, which is particularly useful in managing complex symptoms related to cancer (2, 30). However, Iran’s lack of specialized PC centers, digital infrastructure, and supportive policies hampers such advances. In Iran, barriers to implementing digital health include limited access to high-speed internet in rural areas and a lack of funding to develop information technology (IT) infrastructure in health centers. In addition, the lack of adequate training for nurses in the use of digital tools limits the adoption of new technologies (12, 33). Addressing geographic disparities requires establishing a national telemedicine platform tailored for oncology and PC services. Pilot implementation of virtual symptom monitoring tools like PROMs at major cancer centers is recommended. Integrating AI-based CDSS within nursing workflows could improve symptom cluster detection and guide personalized care plans, especially in complex cases.

Future research should prioritize policy development for PC integration in oncology nursing, creation of culturally relevant symptom assessment tools, and formulation of national PC protocols for nurses. Given the lack of independent PC education in Iranian curricula, it is very important to improve nursing education by providing dedicated PC units including symptom cluster assessment, spiritual care, communication, and end-of-life decision-making. To strengthen the capabilities of oncology nurses in PC, effective educational strategies such as simulation-based training and interdisciplinary workshops should be prioritized to improve symptom management skills.

Future research should focus on developing evidence-based clinical protocols and algorithms tailored to the Iranian health context to guide nurses in managing complex symptom clusters. Furthermore, establishing a national certification program for PC nursing, modeled after initiatives like ELNEC, could standardize competencies and elevate the quality of care (34). Finally, limited nurse knowledge often limited to death and dying may foster disinterest or negative attitudes toward end-of-life care, emphasizing the need for comprehensive education to improve both nurse preparedness and patient outcomes (35).

The lack of national policies and specialized training hinders the scalability of PC and places the Iranian health system at a disadvantage compared to global standards that have shown early integration of PC to be effective. In contrast to Iran’s limited and fragmented PC services, countries with established systems (e.g., the United States, Canada, and the Netherlands) offer multidimensional, community-based care, while middle-income countries such as Turkey and Egypt face similar barriers, including hospital-based services and a lack of formal education. These similarities suggest that Iran’s challenges are regionally shared but require policy and educational reforms tailored to specific circumstances, local culture, religion, and other influential factors (20).

To advance palliative nursing in Iran, several practical reforms are needed. First, a national roadmap for integrating telemedicine should be developed, starting with pilot projects in major cancer centers and expanding to underserved areas. Second, the establishment of a national standard nursing certification in PC that ensures competency and improves the quality of care. Initial investment in digital infrastructure and training will lead to improved PC, ultimately reducing hospital costs and improving patients’ QoL, making them cost-effective in the long term (9). Table 1 summarizes the barriers and suggested solutions for PC in oncology nursing in Iran.

| Barriers | Proposed Solutions |

|---|---|

| Lack of specialized nurse training | Designing and implementation of national educational programs and dedicated PC modules in nursing curricula |

| Nursing shortage and high workload | Increasing the employment of trained nurses in the field of PC and optimizing human resource management in oncology centers |

| Cultural barriers in end-of-life care | Training nurses in communication skills to manage cultural sensitivities in end-of-life care |

| The lack of coherent national policies in palliative care | Development of national policies and guidelines for PC integration, establish PC units, and multidisciplinary teams |

| Inadequate digital infrastructure and telemedicine | Implementation of artificial and medical intelligence platforms in oncology palliative medicine care |

Abbreviation: PC, palliative care.

4.1. Conclusions

Oncology nurses in Iran play a critical role in managing cancer-related symptoms across physical, psychological, social, and spiritual domains, but face barriers including limited specialized training in palliative care, workforce shortages, cultural sensitivities, and policy gaps. To increase the quality and access to palliative care, this review advocates a multifaceted approach that incorporates evidence-based strategies such as advanced nurse education through national certification programs, implementation of structured telemedicine systems, and adoption of AI-based clinical decision support tools. Establishing coherent national policy frameworks to support multidisciplinary collaboration and home-based care is essential. By aligning these culturally sensitive strategies with global advances, Iran can significantly improve the effectiveness and accessibility of PC services for cancer patients.