1. Background

Stroke is a rapidly progressive focal or generalized neurological disorder of the cerebrovascular system that disrupts brain function (1). Stroke can occur either as a blockage or reduction of blood supply to the brain (ischemia) or as intracerebral bleeding (hemorrhage), which account for approximately 85% and 15% of stroke cases, respectively. Ischemic stroke (IS) is a consequence of inadequate oxygen and nutrient supply to the brain (2). Stroke is the second leading cause of death and disability worldwide (3).

In Iran, the absolute frequency of strokes in 2019 was 963,512 cases (53.6% females), of which 88.1% were ischemic, 12% were intracerebral hemorrhage, and 4.7% were subarachnoid hemorrhage. Additionally, the number of deaths due to stroke was 40,912 (4). Strokes are among the most common causes of physical and mental disabilities in societies, imposing significant challenges and economic burdens on healthcare systems and individuals (1, 5). Identifying the risk factors for stroke is one of the most important epidemiological aspects of preventive strategies and has led to a significant reduction in stroke incidence and increased life expectancy in developed countries (6).

Despite these advances, the incidence of stroke continues to rise in the Middle East and North Africa, making it a major health problem in these regions (7). It is well established that chronic disorders are major risk factors for the development of stroke (8, 9). Furthermore, the coexistence of stroke with underlying chronic disorders is associated with a considerable financial burden (10). It has also been shown that underlying disorders directly influence survival rates following stroke (11, 12). Vascular abnormalities in patients with chronic diseases, such as diabetes, are major pathogenic risk factors (13, 14).

Since the incidence of IS has increased among younger individuals, recent literature has focused on identifying its risk factors and predictors (15, 16). Moreover, it has been reported that mortality due to IS is projected to reach 4.90 million by 2030 (17). Factors such as behavioral factors, smoking, high-sodium diet, high systolic blood pressure, elevated low-density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol, kidney dysfunction, high fasting plasma glucose, and high Body Mass Index are major risk factors, particularly among younger people in regions with a low sociodemographic index (17).

However, other factors such as age, sex, family history, and race/ethnicity are non-modifiable (16, 18, 19). In contrast, various identified risk factors, including comorbidities, can contribute to the development of hemorrhagic transformation following thrombolytic therapy (20, 21). Given that stroke is, to some extent, preventable, recognizing its risk factors and predictors of adverse outcomes can help reduce the burden of disease in the country.

2. Objectives

This study aims to further investigate the risk factors for IS and the predictors of mortality in patients with IS.

3. Methods

3.1. Study Design

This retrospective cross-sectional study was conducted on patients with IS who were referred to the emergency department of Golestan Hospital in Ahvaz during 2022 - 2023. All procedures involving human participants were performed in accordance with the ethical standards of the National Research Committee and with the 2008 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

3.1.1. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

Non-random sampling was conducted based on predefined inclusion and exclusion criteria.

3.1.1.1. Inclusion Criteria

Patients with IS who were referred to the emergency department with symptoms such as dizziness, diplopia, confusion, severe headache, hemiparesis, paraparesis, ataxia, drowsiness, and/or Bell's palsy were evaluated. The National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale (NIHSS) was used to assess patients. Definitive diagnosis of IS was made based on computed tomography (CT) scan findings (22). In patients with suspected IS and a normal CT scan, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) was performed (22). The CT scan and MRI results were evaluated by an emergency medicine specialist, and the final diagnosis was confirmed by a neurosurgeon.

3.1.1.2. Exclusion Criteria

Patients were excluded if they had hemorrhagic stroke, blood clots or vessel narrowing diagnosed by cerebral angiography, cerebral hemorrhage caused by trauma, brain tumors, those who died before initial laboratory tests could be performed, or those with incomplete documentation.

3.2. Data Collection

Data collected included demographic information, underlying disorders, length of hospitalization, and final outcome. Blood samples were collected from all patients upon emergency admission for laboratory evaluation. Laboratory tests included complete blood count (CBC), prothrombin time (PT; Fisher PT 4 mL, Iran), partial thromboplastin time (PTT; Fisher PTT 4 mL, Iran), international normalized ratio (INR), fasting blood sugar (FBS) (ENZYMATIC/GOD-PAP, PARS PEYVAND, Iran), triglyceride, high-density lipoprotein (HDL), LDL, and cholesterol (ZiestChem Diagnostics, Iran). All laboratory examinations were performed in the hospital laboratory. Hyperglycemia was defined as a blood glucose level greater than 125 mg/dL. Additionally, data regarding blood pressure, comorbidities, length of hospitalization, and survival status were extracted from medical records for analysis.

3.3. Sample Size

The sample size was calculated based on the recent prevalence report of IS in Iran (88.1%) (4), with d = 0.08 and α = 0.05. The minimum sample size of 64 patients was calculated using the following formula:

Nevertheless, to better elucidate the exact relationship between variables, the maximum number of patients referred to the hospital during the study period was recruited.

3.4. Statistical Analysis

Variables were expressed as mean and standard deviation (SD) and/or frequency, depending on their statistical nature. The normality of data was assessed using the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test. The t-test or Mann-Whitney U test was used to investigate the impact of quantitative parameters in IS. Additionally, the univariate Cox proportional hazards model was used to identify independent prognostic factors. Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS version 26 statistical software (SPSS, Inc., IL, USA). A P-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

4. Results

4.1. Baseline Characteristics of Patients

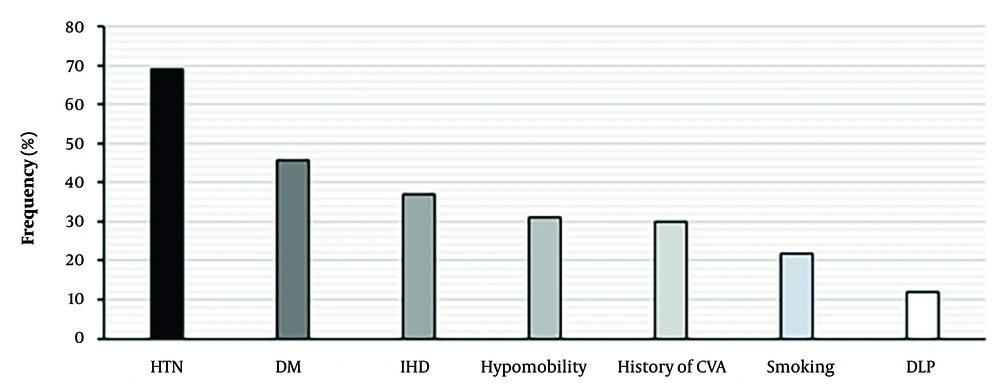

A total of 270 patients with IS were assessed, including 157 men and 113 women. The mean age of participants was 65.17 ± 12.71 years. There was no significant difference in average age between the two sexes (P = 0.27). The incidence of IS was significantly higher in men [P = 0.0002, OR (95% CI): 1.93 (1.371 - 2.718)] and in patients aged 60 years and older (P = 0.0001). A substantial proportion of patients had a history of stroke (30%). The most common comorbidities among patients were hypertension (68.9%), diabetes (45.6%), ischemic heart disease (37%), smoking (21.9%), and dyslipidemia (11.9%; Table 1, Figure 1).

| Variables | IS (N = 270) | P-Value |

| Age (y) | 65.17 ± 12.71 | 0.27 |

| Male | 66.24 ± 11.66 | |

| Female | 63.91 ± 13.87 | |

| Age groups (y) | < 0.0001 | |

| 25 - 39 | 13 (4.8) | |

| 40 - 59 | 73 (27) | |

| ≥ 60 | 184 (68.2) | |

| Gender | 0.0002 | |

| Male | 157 (58.1) | |

| Female | 113 (41.9) | |

| History | 0.36 | |

| CVA | 81 (30) | |

| Hypomobility | 84 (31.1) | |

| Smoking | 59 (21.9) | |

| DM | 123 (45.6) | |

| IHD | 100 (37) | |

| HTN | 186 (68.9) | |

| DLP | 32 (11.9) | |

| Length of hospitalization (d) | 4.67 ± 3.04 | 0.03 |

| Deceased cases | 3.58 ± 1.85 | |

| Alive cases | 4.81 ± 3.14 | |

| Mortality rate | 31 (11.5) | - |

Abbreviations: IS, ischemic stroke; CVA, cerebrovascular accident; DM, diabetes mellitus; IHD, ischemic heart disease; HTN, hypertension; DLP, dyslipidemia.

a Values are expressed as mean ± standard deviation (SD) or No. (%).

The mean length of hospitalization was 4.67 ± 3.04 days, which was significantly shorter in deceased patients than in surviving patients (P = 0.03). In total, 31 patients died (Table 1).

4.2. Laboratory Findings

The results of laboratory tests upon admission showed that, among all biomarkers, the hemoglobin level was abnormally low in a significant percentage of patients with IS (63.7%), and anemia was significantly associated with the incidence of IS (P = 0.0001). Additionally, the level of FBS was abnormally high in a substantial proportion of patients (88.5%), and this hyperglycemia was correlated with IS (P = 0.0001). The levels of PT and PTT were abnormally high in 22 - 25% of patients, although their levels were within the normal range in more than 70% of patients. The levels of other biomarkers were within normal ranges in most patients (Table 2).

| Biomarkers | IS (N = 270) |

|---|---|

| WBC (103 μL) | 11.1 ± 4.14 |

| Hb (g/dL) | 11.39 ± 2.18 |

| Patients with normal range | 98 (36.3) |

| Patients with low abnormal range | 172 (63.7) |

| P-value | < 0.0001 |

| PLT (109/L) | 247.51 ± 96.46 |

| Patients with normal range | 233 (86.3) |

| Patients with low abnormal range | 37 (13.7) |

| PT (s) | 12.91 ± 1.18 |

| Patients with normal range | 202 (74.8) |

| Patients with high abnormal level | 68 (25.2) |

| PTT (s) | 36.41 ± 8.66 |

| Patients with normal range | 210 (77.8) |

| Patients with high abnormal level | 60 (22.2) |

| INR | 1.49 ± 1.89 |

| Patients with INR < 1.5 | 239 (88.5) |

| Patients with INR > 1.5 | 31 (11.5) |

| Triglyceride (mg/dL) | 119.72 ± 42.39 |

| Patients with normal range | 207 (76.7) |

| Patients with borderline high range | 56 (20.7) |

| Patients with high range | 7 (2.6) |

| Total cholesterol (mg/dL) | 164.35 ± 59.55 |

| Patients with normal range | 219 (81.1) |

| Patients with borderline high range | 25 (9.3) |

| Patients with high range | 26 (9.6) |

| HDL (mg/dL) | 56.19 ± 17.77 |

| Patients with normal range | 261 (96.7) |

| Patients with low abnormal range | 9 (3.3) |

| LDL (mg/dL) | 94.5 ± 40.61 |

| Patients with normal range | 249 (92.2) |

| Patients with high abnormal range | 21 (7.8) |

| FBS (mg/dL) | 174.76 ± 87.64 |

| Patients with normal range | 31 (11.5) |

| Patients with high abnormal range | 239 (88.5) |

| P-value | < 0.0001 |

Abbreviations: IS, ischemic stroke; PT, prothrombin time; PTT, partial thromboplastin time; INR, international normalized ratio; HDL, high-density lipoprotein; LDL, low-density lipoproteins; FBS, fasting blood sugar.

a Values are expressed as mean ± standard deviation (SD) or No. (%).

4.3. Association of Different Factors with Mortality Risk

Univariate Cox analyses were performed, adjusting for all variables, to identify possible predictors of mortality in patients with IS. The results indicated that none of the demographic, clinical, or laboratory factors had a significant association with mortality in these patients (P > 0.05, Table 3).

| Variables | Univariate Analysis | Multivariate Analysis with all Significant Variables | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR (95% CI) | P-Value | Adjusted HR (95% CI) | P-Value | |

| Gender (M:1) | 1.250 (0.605 - 2.582) | 0.54 | - | - |

| Age (y) | 0.978 (0.953 - 1.005) | 0.1 | - | - |

| History of CVA | 1.259 (0.610 - 2.598) | 0.53 | - | - |

| Hypomobility | 1.121 (0.537 - 2.342) | 0.76 | - | - |

| Smoking | 0.627 (0.241 - 1.636) | 0.34 | - | - |

| DM | 0.813 (0.398 - 1.663) | 0.57 | - | - |

| IHD | 0.655 (0.301 - 1.426) | 0.28 | - | - |

| HTN | 1.326 (0.593 - 2.964) | 0.49 | - | - |

| DLP | 1.471 (0.565 - 3.834) | 0.43 | - | - |

| WBC (103 μL) | 1.025 (0.949 - 1.108) | 0.53 | - | - |

| Hb (g/dL) | 1.019 (0.865 - 1.2) | 0.82 | - | - |

| PLT (109/L) | 0.999 (0.996 - 1.003) | 0.66 | - | - |

| PT (s) | 0.979 (0.72 - 1.329) | 0.89 | - | - |

| PTT (s) | 1.029 (0.997 - 1.062) | 0.08 | - | - |

| INR | 0.799 (0.420 - 1.52) | 0.49 | - | - |

| TG (mg/dL) | 0.996 (0.988 - 1.005) | 0.38 | - | - |

| Total cholesterol (mg/dL) | 1 (0.994 - 1.006) | 0.97 | - | - |

| HDL (mg/dL) | 0.997 (0.977 - 1.017) | 0.77 | - | - |

| LDL (mg/dL) | 1.003 (0.996 - 1.011) | 0.36 | - | - |

| Blood sugar (mg/dL) | 1.001 (0.997 - 1.005) | 0.55 | - | - |

Abbreviations: CVA, cerebrovascular accident; DM, diabetes mellitus; IHD, ischemic heart disease; HTN, hypertension; DLP, dyslipidemia; PT, prothrombin time; PTT, partial thromboplastin time; INR, international normalized ratio; HDL, high-density lipoprotein; LDL, low-density lipoproteins.

5. Discussion

The present study demonstrated that IS was more prevalent among men and in elderly patients aged 60 years and older. The laboratory profiles of patients can reflect their overall health status and provide valuable insights for treatment decisions (6, 7). According to a systematic review and meta-analysis by Misra et al., matrix metalloproteinase-9, brain natriuretic peptide, and D-dimer significantly differentiate IS from intracerebral hemorrhage, stroke mimics, and healthy individuals (23). In 2021, Bustamante et al. evaluated the laboratory profiles of 154 patients with IS and 35 with intracerebral hemorrhage upon admission. Their results indicated that a biomarker panel consisting of N-terminal proB-type natriuretic peptide, retinol binding protein 4, and glial fibrillary acid protein had sufficient power to distinguish IS from intracerebral hemorrhage (24). In this context, our results showed that abnormally low levels of hemoglobin (anemia) and elevated FBS (hyperglycemia) appear to be strong diagnostic markers of IS.

Zhong et al. assessed 3,405 patients with IS and reported that elevated complement C3, high-sensitivity C-reactive protein, hepatocyte growth factor, matrix metalloproteinase-9, and anti-phosphatidylserine antibodies were each associated with adverse outcomes (death and major disability) in patients with IS (25). In this regard, we analyzed the prognostic significance of multiple biomarkers, including white blood cell count, hemoglobin, platelet count, PT, PTT, INR, triglyceride, total cholesterol, HDL, LDL, and blood sugar. Our findings did not reveal any predictive factors for mortality rate in IS patients; however, previous studies have shown that factors such as statin use, history of cardiac failure, and NIHSS score can predict the mortality rate up to three years following IS (26). In our study, we found that age greater than 60 years was associated with higher mortality. Among the inflammatory cells, we evaluated only the total white blood cell count. Recently, the Systemic Inflammation Response Index has been introduced as a valuable prognostic marker for 30- and 90-day survival in patients with acute IS (27). The Systemic Inflammation Response Index is calculated by the composite ratio of peripheral neutrophil, monocyte, and lymphocyte counts, and a value ≥ 4.57 is associated with higher mortality in acute IS, particularly in diabetic patients (27). Similarly, another predictor, the Alberta Stroke Program Early CT score, has shown an inverse correlation with IS survival. The Alberta Stroke Program Early CT score is associated with age, monocyte values, and high-sensitivity cardiac troponin I in diabetic patients (28).

Our results indicated that diabetes could not predict survival in IS patients, but fasting blood glucose levels were higher in deceased patients. Consistent with our findings, Ilut et al. have shown that diabetes was not correlated with mortality in IS (29). However, the level of dependency in patients is an essential factor in the final outcome of IS. Patients with moderate dependency have a relatively favorable prognosis, while three-month and three-year mortality rates are higher in patients with severe and moderately severe dependency prior to stroke (30). These findings may explain the contradictory results observed in different studies.

Contrary to expectations, we did not find an association between hypertension and mortality in IS. These results may be attributed to the relatively small sample size, heterogeneous patient population, and short follow-up period. Although hypertension is considered a predictive factor for recurrent IS (31), our findings did not confirm its association with mortality.

The pathophysiological roles of underlying disorders, advanced age, and high NIHSS scores are well established and recognized as influential risk factors for mortality in patients with IS. The heterogeneity observed among study results can largely be attributed to the selection of patients with varying stroke severities and individual immune system statuses. To address this inconsistency and mitigate confounding outcomes, predictive prognostic models have been developed. These prognostic models are essential tools for predicting clinical outcomes in patients with IS by integrating a combination of clinical, imaging, and laboratory variables (32). Unlike the isolated assessment of individual risk factors such as age, hypertension, or diabetes, which primarily focus on the probability of stroke occurrence, integrated prognostic models provide a significantly more accurate and personalized prediction of disease outcomes through the quantitative combination of these factors with acute data points, including neurological severity, imaging findings, and acute blood glucose levels (33). This comprehensive approach accounts for the complex interactions between various variables and calculates the statistical weight of each in the final outcome (34). Consequently, these models are not only superior in predicting outcomes such as functional disability, mortality, or stroke recurrence, but also serve as a guide for clinical decision-making, selection of optimal treatment strategies, and providing personalized counseling to patients and their families (35). While risk factors indicate the "causes", prognostic models predict the "consequences", highlighting their invaluable role in personalized medicine and clinical management. Therefore, to eliminate contradictory results across studies, it is recommended that future efforts focus on enhancing existing prognostic models, which demonstrate higher efficacy than conventional risk factors alone (35).

5.1. Conclusions

The present study suggests that male gender, older age, hypertension, diabetes, ischemic heart disease, previous stroke, hyperglycemia, and anemia are risk factors for IS. However, none of these factors showed a significant association with mortality risk. The absence of risk factors alone does not guarantee a favorable outcome for IS patients. Therefore, the cumulative effect of risk factors and other variables should be incorporated into the development of current prognostic models. In addition, consistent with previous studies, the present data highlight the importance of implementing educational interventions to increase awareness. These findings can be useful for healthcare providers.

5.2. Study Strengths and Limitations

The main strength of this study is the assessment of a broad panel of demographic, clinical, and laboratory factors in all patients. However, the retrospective nature of the study limited the statistical accuracy of the results. Additionally, this single-center study is prone to selection bias and restricts the generalizability of the findings. Accurate identification of all prognostic factors for adverse outcomes requires a larger-scale study. Furthermore, data recording errors, incomplete records, and potential selection bias due to the study being conducted at a single public hospital are additional limitations.