1. Background

Dysregulation of serum phosphorus, calcium, blood urea nitrogen (BUN), and creatinine is a central driver of disease burden in patients receiving maintenance hemodialysis and is associated with secondary hyperparathyroidism, vascular calcification, recurrent hospitalization, and mortality. The KDIGO 2017 guideline emphasizes serial monitoring and trend-based clinical decision-making for the control of calcium, phosphorus, and iPTH, noting that reliance on single time-point measurements can be misleading (1). In a classic analysis, higher serum phosphorus as well as the calcium-phosphorus product (Ca × P) were each linked to a significantly increased risk of death among hemodialysis patients (2). Nutritional studies likewise indicate that higher dietary phosphorus intake and an elevated phosphorus-to-protein ratio are associated with greater mortality (3), and that simultaneous out-of-range values for iPTH, calcium, and phosphorus further compound risk (4).

Despite broad consensus on the importance of these biochemical targets, traditional information-transfer education alone is insufficient to produce sustained changes in home behaviors such as the timing of phosphate-binder intake, food selection, and fluid/sodium control; “dietary knowledge” does not reliably translate into adherence (5). Conversely, behavioral/biological markers including fluctuations in BUN and phosphorus and interdialytic weight gain do reflect adherence, but passively tracking them without a structured family-level intervention rarely converts potential into actual behavior change (6). The literature on phosphorus-focused educational interventions is heterogeneous: Some trials have shown no definitive effect on Ca × P or phosphorus, whereas more intensive programs that stress binder timing and practical skills have reported meaningful improvements in phosphorus control and adherence (7, 8).

The family-centered empowerment model (FCEM) comprises four phases: Perceived threat, self-efficacy/problem-solving, self-esteem through participatory education, and evaluations designed to shift the locus of change from one-way teaching to the redesign of everyday decisions within the family context. Empowerment-based studies in chronic illness — including ESRD — have reported improved adherence and favorable movement in selected clinical/laboratory indices (9). The innovation of this approach lies in explicitly mapping intervention components to target behaviors (e.g., precise binder timing relative to meals, low-phosphorus substitutions that preserve adequate protein intake, and strategies for fluid/sodium control). The present study’s added value is its exclusive focus on laboratory endpoints (calcium, phosphorus, BUN, creatinine) and short-interval repeated assessments (baseline, 1 month, 2 months) to test time × group interactions and more credibly attribute biologic change to FCEM’s behavioral components (1, 10).

Even small but sustained reductions in phosphorus or BUN can decrease expenditures on binders, reduce metabolically driven adverse events and related hospitalizations, and improve dialysis unit performance metrics (2, 11).

2. Objectives

This work aligns with current unit-level needs to achieve measurable laboratory outcomes and offers practical utility for nurses and managers (implementation and trend monitoring), researchers (generalization and mechanism testing), policymakers (integration into education/quality bundles), and patients/families (actionable, day-to-day tools) (3, 5, 12). Overall, the existing literature has assessed empowerment/education largely through psychometric or knowledge-based outcomes, with inconsistent laboratory results. The principal gap remains the scarcity of structured, family-centered evaluations that use exclusively laboratory endpoints and longitudinal time × group analyses — a gap that the present study is designed to address (1, 7-9).

3. Methods

3.1. Study Design and Setting

We conducted a two-arm, quasi-experimental study in the hemodialysis unit of Imam Ali Hospital (Zahedan University of Medical Sciences, Zahedan, Iran).

3.2. Participants and Sample Size

Adult patients receiving maintenance hemodialysis were eligible. The required sample size per group was calculated for a two-sample comparison of means (α = 0.05, power = 0.90) using prior variance/effect estimates; to accommodate attrition, we targeted n = 50 per group (n = 100) (13).

3.3. Eligibility Criteria

1. Inclusion: No cognitive disability; intact hearing/speech/communication; 2 - 3 hemodialysis sessions per week; ≥ 6 months on hemodialysis; neither the patient nor the primary family caregiver affiliated with healthcare staff; no recent or concurrent formal self-care training.

2. Exclusion: Incident/worsening comorbidity precluding participation; > 1 session absence by the patient or caregiver.

3.4. Allocation and Blinding

Allocation was based on dialysis shift (intervention = afternoon; control = morning), classifying the design as quasi-experimental. Baseline comparability was examined; an imbalance in the primary caregiver relationship is reported and treated as a potential confounder. Blinding of participants and facilitators was not feasible. Laboratory outcomes were abstracted from routine records, and data entry/analysis were conducted without formal blinding.

3.5. Intervention (Family-Centered Empowerment Model)

The intervention comprised four weekly 90-minute small-group sessions attended by each patient with a primary family caregiver.

1. Perceived threat: Disease course/complications; diet/physical activity; laboratory targets/testing.

2. Problem-solving/self-efficacy: Barrier mapping; precise phosphate-binder timing; low-phosphorus/adequate-protein substitutions; fluid/sodium restriction; dialysis tips.

3. Participatory education/self-esteem: Patient-to-family teach-back.

4. Evaluation: Brief Q&A at the start of each session; reinforcement of home routines.

Sessions were delivered on-site using slides/whiteboard. Brief telephone support was available between sessions (14)

3.6. Intervention Fidelity

All sessions were delivered by the same nurse-researcher using standardized slides and a written booklet. Attendance was monitored; participants with more than one absence would be excluded.

3.7. Control Condition

Controls received usual care and no study education during the 2-month follow-up. To minimize contamination, a single 2-hour education session and the booklet were provided after the final assessment.

3.8. Outcomes and Data Collection

Demographics (age, sex, chronic kidney disease (CKD) duration, dialysis vintage, primary caregiver relationship) and laboratory indices (serum calcium, phosphorus, BUN, creatinine) were abstracted at baseline, 1 month, and 2 months.

3.9. Laboratory Measurements and Timing

Measurements were performed according to hospital laboratory protocols. Timing relative to dialysis was not fully standardized across participants and is acknowledged as a study limitation.

3.10. Statistical Analysis

Analyses were conducted in SPSS v22. Descriptive statistics (frequency, percentage, mean ± SD, range) were reported. Baseline comparisons used independent t-tests and chi-square tests. Longitudinal effects (time, group, and time × group interaction) were tested with repeated-measures ANOVA. Normality was assessed by Shapiro-Wilk; when sphericity was violated, Greenhouse-Geisser corrections were applied. Two-sided α = 0.05.

3.11. Ethics and Trial Registration

The study was approved by the Zahedan University of Medical Sciences Ethics Committee (IR.ZAUMS.REC.1395.237), and written informed consent was obtained. The trial was not prospectively registered in a public registry; this is acknowledged as a limitation.

4. Results

4.1. Assumption Checks

Normality was assessed using the Shapiro-Wilk test. When sphericity was violated, Greenhouse-Geisser corrections were applied. Between-group P-values at each time point reflect independent t-tests; longitudinal time × group effects were tested with repeated-measures ANOVA (two-sided α = 0.05).

4.2. Demographic Characteristics

At enrollment, the intervention and control groups were comparable for age, sex, CKD duration, and dialysis vintage, with no significant differences. A single imbalance was observed for the primary caregiver relationship (P = 0.006). Full baseline data are presented in Table 1.

| Variables | Control (N = 50) | Intervention (N = 50) | Test | P-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (y) | 47.24 ± 16.14 | 48.18 ± 15.78 | 0.294 b | 0.76 |

| CKD duration (mo) | 21.14 ± 27.88 | 34.56 ± 26.79 | 0.592 b | 0.55 |

| Dialysis vintage (mo) | 46.68 ± 33.56 | 52.08 ± 55.04 | 2.454 b | 0.16 |

| Sex | 0.041 c | 0.84 | ||

| Male | 28 (56.0) | 29 (58.0) | ||

| Female | 22 (44.0) | 21 (42.0) | ||

| Primary caregiver | 14.52 c | 0.006 | ||

| Spouse | 7 (14.0) | 17 (34.0) | ||

| Mother | 2 (4.0) | 1 (2.0) | ||

| Child | 24 (48.0) | 25 (50.0) | ||

| Sibling | 17 (34.0) | 7 (14.0) |

Abbreviation: CKD, chronic kidney disease.

a Values are expressed as mean ± SD or No. (%).

b Independent t-test.

c Chi-square test.

4.3. Longitudinal Laboratory Outcomes

Repeated-measures analyses demonstrated significant time × group interactions for all four laboratory endpoints — serum calcium, phosphorus, BUN, and creatinine — favoring the intervention arm (all P < 0.001; Table 2).

| Laboratory Indices (mg/dL) | Groups | Between Groups P- Value (Baseline/1 mo/2 mo) b | Time × Group P-Value c | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | 1 mo | 2 mo | |||

| Calcium | 0.93/< 0.001/< 0.001 | < 0.001 | |||

| Intervention | 8.10 ± 0.48 | 8.90 ± 0.46 | 9.50 ± 0.45 | ||

| Control | 8.30 ± 0.66 | 8.30 ± 0.62 | 8.40 ± 0.63 | ||

| Phosphorus | 0.80/< 0.001/< 0.001 | < 0.001 | |||

| Intervention | 5.10 ± 0.38 | 5.10 ± 0.38 | 3.90 ± 0.40 | ||

| Control | 5.10 ± 0.35 | 5.20 ± 0.44 | 5.40 ± 0.48 | ||

| BUN | 0.70/0.01/< 0.001 | < 0.001 | |||

| Intervention | 69.14 ± 16.90 | 57.15 ± 14.17 | 48.95 ± 12.40 | ||

| Control | 67.41 ± 29.61 | 66.39 ± 21.82 | 68.98 ± 24.91 | ||

| Creatinine | 0.20/0.009/< 0.001 | < 0.001 | |||

| Intervention | 8.47 ± 2.05 | 7.64 ± 2.41 | 7.34 ± 2.49 | ||

| Control | 8.84 ± 2.06 | 7.94 ± 2.57 | 7.94 ± 2.57 | ||

Abbreviation: BUN, blood urea nitrogen.

a Values are expressed as mean ± SD.

b Between-group P-values at each time point are from independent t-tests.

c Time × group P-values are from repeated-measures ANOVA with Greenhouse-Geisser correction when sphericity was violated.

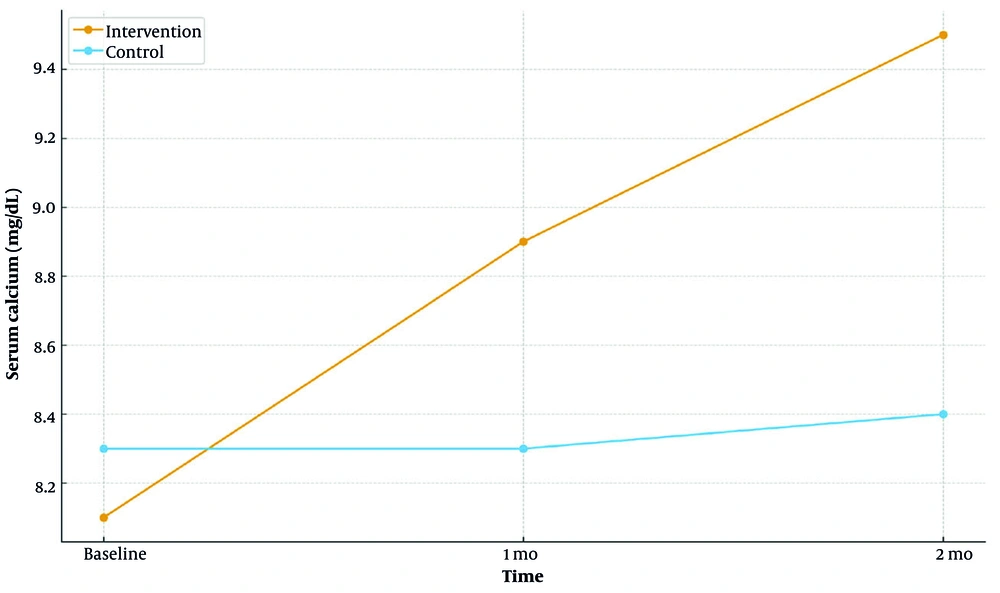

4.3.1. Calcium

Mean calcium increased at 1 and 2 months in the intervention group, whereas the control group showed a decrease or stability. Between-group differences were not significant at baseline but became significant at 1 and 2 months (both P < 0.001, independent t-tests).

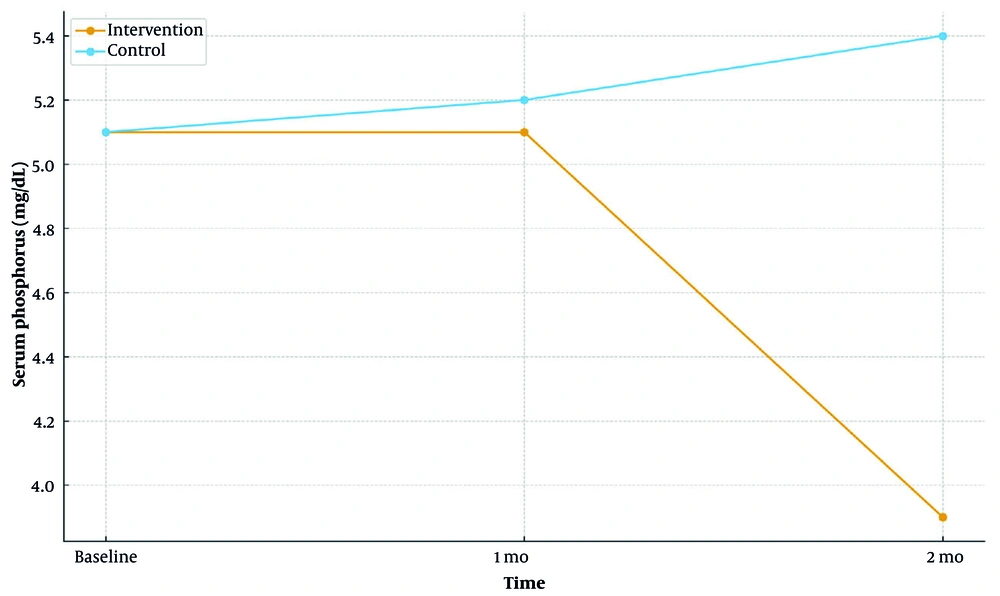

4.3.2. Phosphorus

Mean phosphorus declined over time in the intervention arm and rose in controls. Groups did not differ at baseline; between-group differences were significant at 1 and 2 months (both P < 0.001).

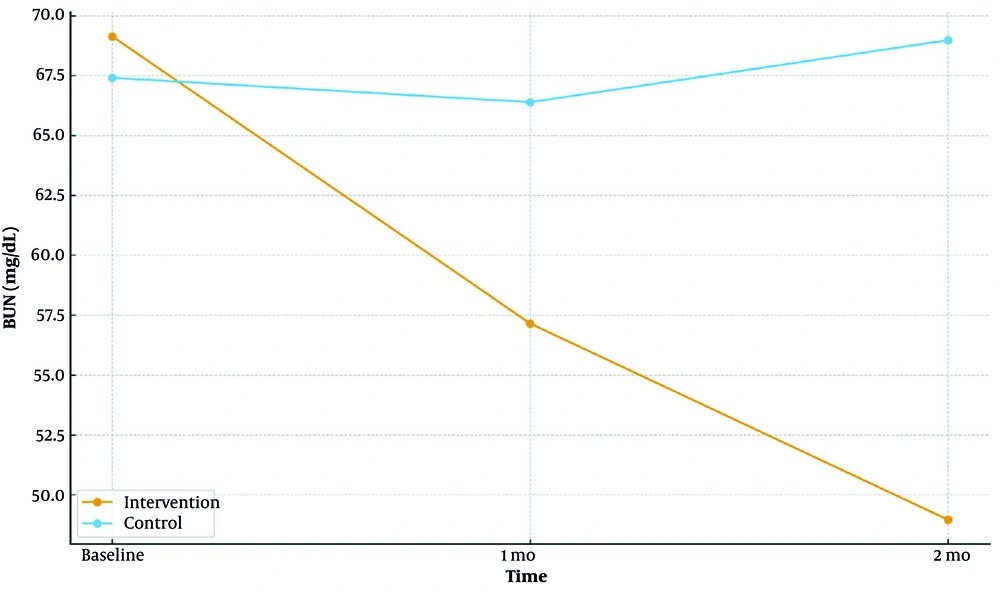

4.3.3. Blood Urea Nitrogen

The intervention group exhibited a reduction in BUN, while the control group showed an increase. Between-group differences were non-significant at baseline but became significant at 1 month (P = 0.01) and 2 months (P < 0.001).

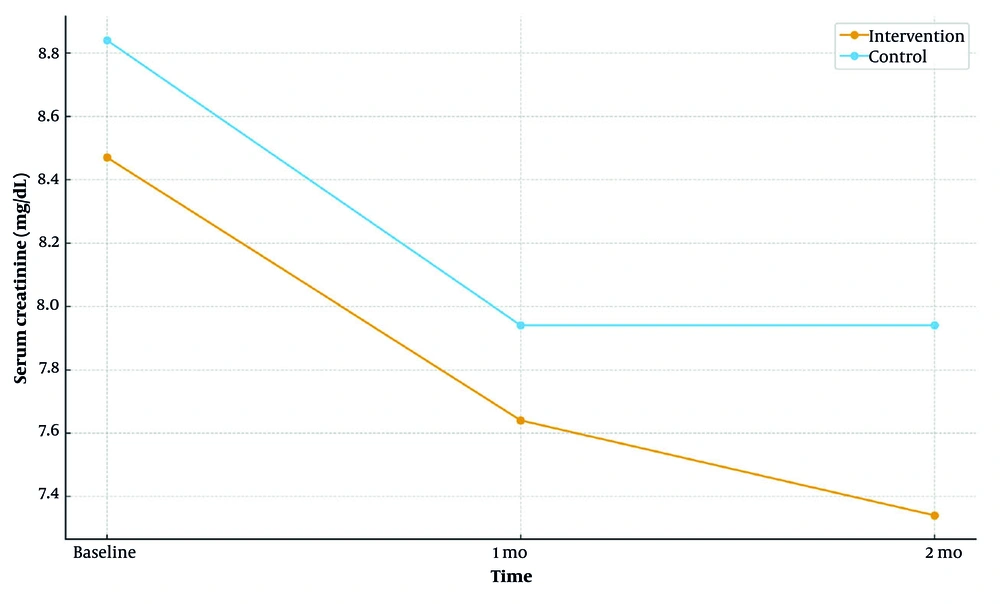

4.3.4. Creatinine

Serum creatinine decreased at 1 and 2 months in the intervention arm but increased or was stable in controls; between-group differences were significant at 1 month (P = 0.009) and 2 months (P < 0.001).

Consistent with trend-based recommendations, longitudinal trajectories for calcium, phosphorus, BUN, and creatinine at baseline, 1 month, and 2 months are depicted in Figures 1 - 4, complementing the estimates reported in Table 2.

Longitudinal mean serum creatinine at baseline, 1 month, and 2 months by group (intervention vs control; Table 2)

Longitudinal mean blood urea nitrogen (BUN) at baseline, 1 month, and 2 months by group (intervention vs control; Table 2)

Longitudinal mean serum phosphorus at baseline, 1 month, and 2 months by group (intervention vs control; Table 2)

Longitudinal mean serum calcium at baseline, 1 month, and 2 months by group (intervention vs control; Table 2)

5. Discussion

The FCEM was associated with more favorable longitudinal trends across all laboratory outcomes: Serum calcium increased, whereas phosphorus, BUN, and creatinine decreased compared with usual care (Table 2 and Figures 1 - 4). These trajectories are consistent with literature indicating that targeted education and empowerment can improve calcium/phosphorus control and enhance adherence to diet and phosphate-binder timing (15-18). By contrast, studies without an explicit family-anchored framework or with brief follow-up have sometimes failed to show calcium gains, often attributing null results to short intervention windows, baseline values within normal ranges, or adherence barriers (14, 19). Guideline statements also emphasize trend-based management of mineral metabolism rather than single measurements (1).

5.1. Calcium

5.1.1. Interpretation

The upward trend in calcium among FCEM participants may reflect better binder timing, improved vitamin D adherence, and dietary counseling that preserved adequate protein while moderating phosphorus density. Such patient-caregiver behaviors are precisely what FCEM targets through problem-solving and teach-back.

5.1.2. Comparison with Literature

Prior empowerment/education interventions have variably influenced calcium, with null effects more likely when baseline values are normal, follow-up is short, or treatment intensity is low (19, 20). Our pattern aligns with reports where structured, behavior-focused training produced movement toward recommended ranges (15).

5.1.3. Clinical Relevance

From a practice standpoint, sustained calcium normalization supports KDIGO’s trend-based management of CKD-MBD (1).

5.2. Phosphorus

5.2.1. Interpretation

The FCEM was associated with declining phosphorus over 1 - 2 months. Mechanistically, this likely reflects precise phosphate-binder timing, food substitutions with lower phosphorus-to-protein ratios, and caregiver-supported meal planning.

5.2.2. Comparison with Literature

Multiple reports link phosphorus-focused education to improved serum control and adherence (17, 18, 21, 22), whereas non-family-anchored or low-dose programs often show attenuated effects (19, 20). Our findings are congruent with the former body of evidence.

5.2.3. Clinical Relevance

Even modest, sustained reductions in phosphorus may reduce CKD-MBD risk and downstream events, consistent with guideline priorities (1) and nutrition literature (18).

5.3. Blood Urea Nitrogen

5.3.1. Interpretation

The decline in BUN among FCEM participants suggests improvement in day-to-day diet/fluid decisions and self-efficacy — core behaviors targeted by FCEM.

5.3.2. Comparison with Literature

Prior studies relate better education/adherence to lower BUN and fewer uremic symptoms (17, 23, 24). Our pattern (decline under FCEM vs. rise/stability in usual care) mirrors these associations.

5.3.3. Clinical Relevance

Reducing uremic burden can translate into fewer metabolically driven events and improved well-being (23, 24).

5.4. Creatinine

5.4.1. Interpretation

The downward trend in creatinine under FCEM likely reflects broader adherence (diet/fluid, dialysis tips) and caregiver engagement that extends beyond knowledge acquisition.

5.4.2. Comparison with Literature

Empowerment-based approaches have reported favorable movement in clinical markers when behavioral components are explicit and supported by families (15, 20).

5.4.3. Clinical Relevance

While creatinine is multifactorial, parallel improvements across phosphorus and BUN strengthen the interpretation that household routines shifted in a clinically meaningful direction.

5.5. Caregiver Role and Internal Validity

A baseline imbalance in the primary caregiver relationship may have influenced adherence-related behaviors; a higher proportion of spouses in the intervention arm could enhance daily oversight, acting as an effect modifier. Although the longitudinal trends favor FCEM, this imbalance limits internal validity and motivates adjusted or randomized/cluster-randomized designs in future studies (see also (19, 20) for sensitivity to design features).

5.6. Conclusions

In this quasi-experimental evaluation, the FCEM was associated with clinically meaningful improvements across core laboratory indices in maintenance hemodialysis — higher calcium and lower phosphorus, BUN, and creatinine over two months — relative to usual care. These findings support the premise that structured, family-centered education, when coupled with practical problem-solving and teach-back, can translate knowledge into day-to-day adherence and more favorable biochemical trajectories. From a practice standpoint, FCEM is feasible to implement within routine nursing workflows using brief small-group sessions per shift, standardized slides/checklists, and deliberate engagement of a primary caregiver. Incorporating trend-based monitoring and feedback (serial review of calcium, phosphorus, BUN, creatinine) can reinforce behavior change and help dialysis units move toward recommended biochemical targets while potentially reducing care burden.

At the same time, interpretation should remain cautious given the quasi-experimental, single-center design, baseline caregiver imbalance, short follow-up, lack of blinding, and non-standardized timing of laboratory sampling. Future multi-center studies with 6 - 12-month follow-up, adjustment for caregiver role and dialysis dose, and full reporting of effect sizes with confidence intervals (CIs) are warranted to confirm durability, estimate the magnitude of benefit, and clarify mechanisms.

5.7. Practical Implications for Nursing Practice

The FCEM can be embedded into routine care through brief small-group sessions per shift, utilizing standardized slides/checklists and incorporating teach-back with a primary caregiver. This approach can lead to modest, sustained reductions in phosphorus and BUN, thereby lowering metabolically driven events, medication needs, and hospitalizations, which supports dialysis-unit performance goals (1, 18, 23, 24). Dialysis units seeking pragmatic quality-improvement strategies may consider adopting FCEM as a nurse-led education bundle. This would involve scheduled caregiver participation and routine trend reviews, with a focus on binder timing, phosphorus-aware meal planning, and fluid/sodium management to maintain laboratory control.

5.8. Future Directions

Multi-center studies with 6 - 12-month follow-up are needed to assess durability and generalizability. Designs enabling adjustment for caregiver role and dialysis dose (e.g., mixed-effects models) are encouraged. To aid clinical interpretation, future reports should include effect sizes with 95% CIs and provide model-level outputs to report partial η2 for time × group.

5.9. Strengths

Strengths include the focus on objective laboratory endpoints, explicit mapping of FCEM components to target behaviors, and short-interval assessments capturing the slope of change.

5.10. Limitations

This study has several limitations. First, the quasi-experimental, shift-based allocation and the baseline imbalance in the primary caregiver relationship limit internal validity and raise the possibility of residual confounding. Second, the single-center setting and relatively short, 2-month follow-up constrain generalizability and preclude conclusions about durability. Third, blinding of participants and facilitators was not feasible, and the timing of laboratory measurements relative to dialysis sessions was not fully standardized, which may introduce measurement variability. Fourth, the trial was not prospectively registered. Fifth, model-level statistics were not retained, and post-hoc re-analysis was not permitted; therefore, effect sizes and 95% CIs could not be reported. Furthermore, although intervention fidelity was supported by a single facilitator and standardized materials, detailed session-level attendance logs and potential covariates such as dialysis dose and vitamin D or binder regimens were not analyzed. These limitations, including the single-center setting, shift-based allocation, caregiver-relationship imbalance at baseline, lack of blinding, non-standardized timing of laboratory sampling relative to dialysis, and the 2-month follow-up that precludes durability claims, should be addressed in future, preferably randomized or cluster-randomized, multi-center studies with longer follow-up.