1. Background

Countries worldwide face challenges in preparing health and social systems for demographic transitions. By 2050, approximately 80% of the global older adult population will reside in low- and middle-income countries. Moreover, population aging is accelerating. In 2020, the number of individuals aged 60 years and older surpassed that of children under five. The share of this population is projected to rise from 12% to 22% between 2015 and 2050 (1). Thailand is experiencing rapid population aging, with the proportion of older adults and the old-age dependency ratio steadily increasing. By 2031, it is projected to become a super-aged society (2). According to the Institute for Population and Social Research, life expectancy rose to 77 years in 2021 (men 73.5; women 80.5), reflecting population growth and longevity. These shifts are associated with age-related health problems such as hypertension, diabetes, cardiovascular disease, hyperlipidemia, and osteoarthritis, which affect mental health, leading to stress, anxiety, depression, and reduced psychological well-being (3-5). Similarly, according to the mental health check-in system of the Department of Mental Health (2020 - 2024), 0.67% of older adults reported high stress; 0.92% and 0.28% were at risk of depression and suicide, respectively (6). Prevalent noncommunicable diseases (NCDs) in older adults often require long-term treatment and impose physical and psychological burdens. Such individuals are at increased risk of depression due to stress, neurological changes, medication effects, or a history of mood disorders or suicide (7).

Depression is a major global public health problem with a rising prevalence and profound health, social, and economic impacts. Left untreated, it often becomes chronic, recurrent, and strongly associated with suicide risk. Although not all individuals attempt suicide, mood disorders, including depression and bipolar disorder, are associated with a 60% higher risk of suicide (8). Evidence from Thailand and internationally shows a strong association between depression, suicide risk, and NCDs in older adults. Similarly, the 2023 National Mental Health Survey estimated depression among 961,000 Thais, with a higher prevalence among women and young adults (7). Furthermore, NCDs, particularly diabetes, increase susceptibility to depression and suicidal behavior, highlighting the need for integrated mental health screening and care in primary settings (9, 10). Studies on the prevalence of depression and suicide risk among older adults with NCDs have reported variations by disease type. Depression was found in 42.1% of those with such conditions, 25 - 43.3% in cancer, 25 - 39.6% in diabetes, 17.6% in end-stage renal disease, 14.5 - 20% in ischemic heart disease, and 10 - 27% in stroke (11-13). In Thailand, depression among older adults with chronic NCDs varies regionally: 28.6% in Roi Et province (14); 29.7% in Saensuk Municipality, Chonburi (15); 22.3% in community hospitals in Chiang Rai (16); and 17.2% (mild), 6.3% (moderate), and 3.1% (severe) in Bueng Kha Phroi Subdistrict Health Promoting Hospital, Lam Luk Ka, Pathum Thani (17). Prior studies indicate that the prevalence and associated factors of depression and suicide risk among older adults with NCDs vary by regions, data, samples, study periods, assessment tools, disease conditions, illness duration, and individual factors. Therefore, this study aimed to examine the prevalence and associated factors of depression and suicide risk among older adults with NCDs in Nakhon Chai Burin, Thailand. The findings should highlight their mental health challenges and inform appropriate prevention and management strategies.

2. Objectives

The objective of this study is to examine the prevalence and associated factors of depression and suicide risk among older adults with NCDs in the Nakhon Chai Burin region of Thailand.

3. Methods

This cross-sectional survey included older adults with NCDs in Nakhon Ratchasima, Chaiyaphum, Buriram, and Surin provinces, recruited from NCD clinics at subdistrict health-promoting and community hospitals. The sample of 400 was calculated using Krejcie and Morgan’s formula (18), with inclusion criteria: Age ≥ 60, residence ≥ 1 year, TMSE score ≥ 23, ability to communicate, and consent. Multi-stage cluster sampling selected two districts, each with two subdistricts, per province, and data were obtained from April 2019 to March 2020.

3.1. Research Tools

1. A 16-item sociodemographic questionnaire developed by the researcher on age, sex, marital status, education, income, residence, children, occupation, underlying diseases, illness duration, disease management, family relationships, and community engagement.

2. A 35-item questionnaire by Yodsud, (19) on mental self-care, involving self-awareness, communication, time management, problem-solving, social support, and religious activities. A 4-point Likert scale was used: Low (1.00 - 1.75), moderately low (1.76 - .50), moderately high (2.51 - 3.25), and high (3.26 - 4.00).

3. Depression assessment by the Department of Mental Health Scale (Phra Sri Maha Bodhi Hospital, 2017) (20), with 2 screening questions and 9 items on psychological (6) and somatic (3) symptoms. They were rated 0 - 3, with scores of < 7 = no depression, 7 - 12 = mild, 13 - 18 = moderate, ≥ 19 = severe.

4. An 8-item suicide risk assessment (Phra Sri Maha Bodhi Hospital, 2017) (20) on suicidal thoughts, self-harm, planning, and past attempts, rated 0 - 10; total scores: Zero = no risk, 1 - 8 = low, 9 - 16 = moderate, ≥ 17 = high risk.

5. Quality of life using the Thai EQ-5D-5L [Pattanaphesaj (21)], covering mobility, self-care, usual activities, pain/discomfort, and anxiety/depression, rated from 1 (no problems) to 5 (extreme problems).

3.2. Instrument Validation

Content validity was assessed by three experts, and the questionnaires were revised accordingly. Reliability was assessed with 30 non-participant older adults attending an NCD clinic, resulting in a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.83.

3.3. Data Collection and Participant Protection

This study, part of a project in Nakhon Chai Burin, was approved by the Human Research Ethics Committee of Suranaree University of Technology (COA No. 16/2562, March 13, 2019; renewed, valid until March 12, 2021). Data were collected by researchers and trained local assistants, including nurses and public health officers. Confidentiality was maintained by coding identifiers, securely storing data, destroying records after completion, and reporting results in aggregate without personal information.

3.4. Data Analysis

Quantitative data were analyzed using frequencies, percentages, means, and standard deviations. Associations between factors and depression and suicide risk were assessed using odds ratios (OR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI).

4. Results

4.1. Sociodemographic and Health Characteristics

A total of 400 participants took part in the study, with the majority being female (54.8%) and aged between 60 and 70 years (59.3%; 68.75 ± 10.25). Most participants were married (73.5%), identified as Buddhist (95.0%), and had an education level below high school (75.5%). The majority were unemployed (72.3%) but reported having sufficient household income (71.5%), engaged in community activities (61.5%), and maintained strong family relationships (63.8%). Hypertension was the most prevalent condition (68.3%), followed by hyperlipidemia (30.5%) and diabetes (29.0%). Nearly half of the participants (47.5%) had two or more comorbidities, with a mean illness duration of 9.42 ± 6.93 years, and 68.0% had an illness duration of 10 years or less (Table 1).

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Sex | |

| Male | 45.3 |

| Female | 54.8 |

| Age (y) | |

| 60 - 70 | 59.3 |

| > 70 | 40.8 |

| Marital status | |

| Married | 73.5 |

| Single | 8.8 |

| Widowed/divorced | 17.8 |

| Religion | |

| Buddhist | 95.0 |

| Other | 5.0 |

| Education | |

| Below high school | 75.5 |

| High school or above | 24.5 |

| Employment | |

| Employed | 27.8 |

| Unemployed | 72.3 |

| Chronic conditions | |

| Hypertension | 68.3 |

| Hyperlipidemia | 30.5 |

| Diabetes | 29.0 |

| Heart disease | 6.5 |

| Cancer | 1.5 |

| CVA | 0.5 |

| Other | 3.8 |

| Comorbidity | |

| Single condition | 52.5 |

| ≥ 2 conditions | 47.5 |

| Illness duration (y) | |

| ≤ 10 | 68.0 |

| > 10 | 32.0 |

| Sufficient income | |

| Yes | 71.5 |

| No | 28.5 |

| Community participation | |

| Yes | 61.5 |

| No | 38.5 |

| Family relationships | |

| Good | 63.8 |

| Poor | 36.3 |

a Values are expressed as percentage.

4.2. Self-care, Depression, Suicide Risk, and Quality of Life

A total of 73.5% of participants demonstrated moderately high to high overall mental self-care. In the past two weeks, 38.8% of participants felt sad or hopeless, and 35.8% experienced anhedonia. Depression was identified in 35.3% of participants, with 28.8% experiencing mild depression, 6.0% moderate, and 0.5% severe. Additionally, 12.8% were at risk of suicide, with 10.5% at low risk and 2.3% at moderate risk. Regarding quality of life, many participants most commonly experienced pain/discomfort (46.8%), mobility issues (33%), and anxiety/depression (25.3%, Table 2).

| Assessment Domain | No. (%) |

|---|---|

| Self-care ability (mental health) | |

| Low (low-moderately low) | 106 (26.5) |

| High (moderately high-high) | 294 (73.5) |

| Depression: 2Q | |

| Sad/hopeless | 155 (38.8) |

| Anhedonia | 143 (35.8) |

| Depression: 9Q | |

| No depression | 259 (64.8) |

| Mild | 115 (28.8) |

| Moderate | 24 (6.0) |

| Severe | 2 (0.5) |

| Suicide risk: 8Q | |

| No risk | 349 (87.3) |

| Low | 42 (10.5) |

| Moderate | 9 (2.3) |

| High | 0 (0) |

| Quality of life: EQ-5D-5L | |

| Mobility (problem) | 132 (33.0) |

| Self-care (problem) | 58 (14.5) |

| Daily activities (problem) | 63 (15.8) |

| Pain/discomfort (problem) | 187 (46.8) |

| Anxiety/depression (problem) | 101 (25.3) |

4.3. Factors Associated with Depression

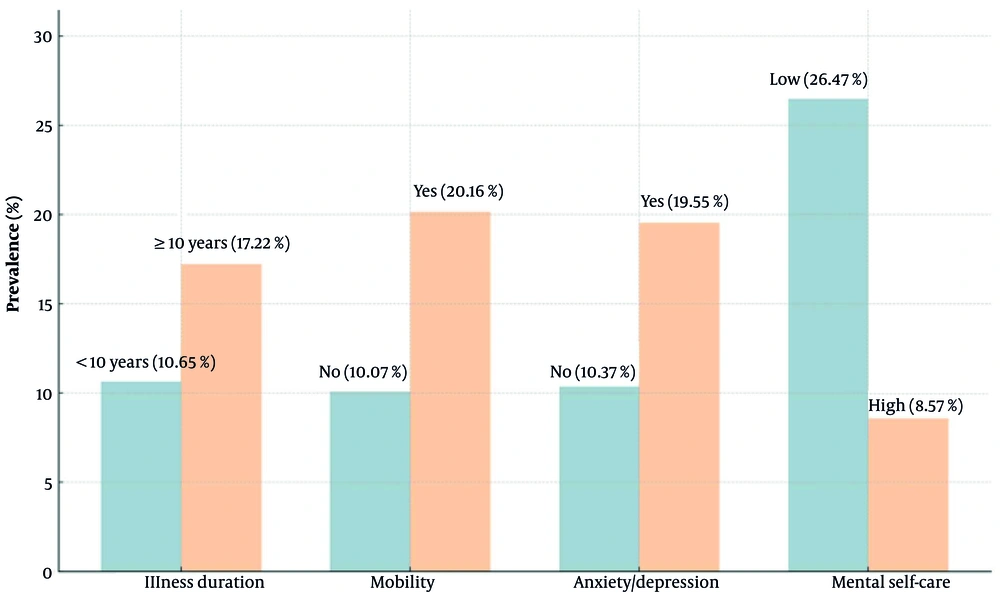

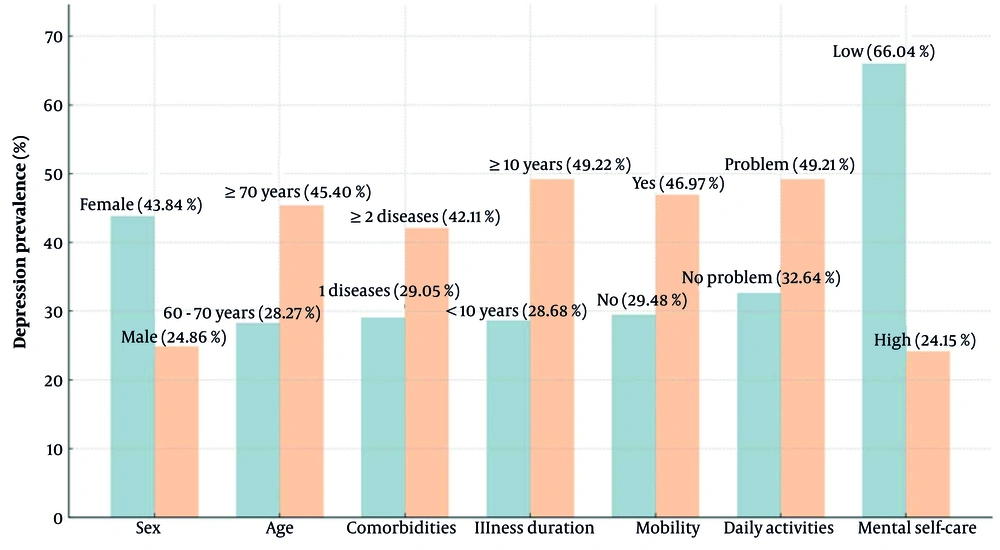

Depression was most prevalent among females, older adults, those with multimorbidity, long illness duration, functional limitations, and low mental self-care, with a prevalence of 66.04% (Figure 1). Similarly, suicide risk was clustered in vulnerable groups, particularly those with an illness duration of 10 years or more, mobility or anxiety problems, and poor mental self-care, with a prevalence of 26.47%. Both outcomes emphasize psychosocial vulnerability as the strongest determinant (Figure 2).

The analysis showed that significant factors associated with depression included female sex (OR = 2.36, 95% CI = 1.53 - 3.63, P < 0.001), age ≥ 70 (OR = 2.11, 95% CI = 1.39 - 3.21, P < 0.001), having two or more comorbidities (OR = 1.77, 95% CI = 1.16 - 2.70, P = 0.008), illness duration of 10 years or more (OR = 2.42, 95% CI = 1.55 - 3.78, P < 0.001), mobility limitations (OR = 2.59, 95% CI = 1.65 - 4.06, P < 0.001), difficulties in daily activities (OR = 2.00, 95% CI = 1.08 - 3.69, P = 0.027), and poor mental self-care (OR = 6.08, 95% CI = 3.60 - 10.30, P < 0.001). Meanwhile, other factors were not significantly associated (Table 3).

| Factors | No. | Depression | OR | 95% CI | P-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | 1.54 - 3.62 | < 0.001 a | |||

| Female | 219 | 96 | 2.36 | ||

| Male | 181 | 45 | Ref | ||

| Age (y) | 1.39 - 3.21 | < 0.001 a | |||

| 60 - 70 | 237 | 67 | Ref | ||

| ≥ 70 | 163 | 74 | 2.11 | ||

| Comorbidities | 1.16 - 2.70 | 0.008 b | |||

| 1 disease | 210 | 61 | Ref | ||

| ≥ 2 diseases | 190 | 80 | 1.77 | ||

| Illness duration (y) | 1.55 - 3.78 | < 0.001 a | |||

| < 10 | 272 | 78 | Ref | ||

| ≥ 10 | 128 | 63 | 2.42 | ||

| Mobility limitations | 1.65 - 4.06 | < 0.001 a | |||

| No | 268 | 79 | Ref | ||

| Yes | 132 | 62 | 2.59 | ||

| Daily activities | 1.08 - 3.69 | 0.027 c | |||

| No problem | 337 | 110 | Ref | ||

| Problem | 63 | 31 | 2.00 | ||

| Mental self-care | 3.60 - 10.30 | < 0.001 a | |||

| Low | 106 | 70 | 6.08 | ||

| High | 294 | 71 | Ref |

Abbreviations: OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence interval; Ref, reference group.

a P < 0.001.

b P < 0.01.

c P < 0.05.

4.4. Factors Associated with Suicide Risk

Multivariate analysis revealed that factors significantly associated with suicide risk included an illness duration of 10 years or more (OR = 1.86, 95% CI = 1.00 - 3.46, P < 0.05), mobility limitations (OR = 1.91, 95% CI = 1.05 - 3.46, P < 0.05), anxiety/depression (OR = 2.12, 95% CI = 1.14 - 3.93, P < 0.05), and inadequate mental self-care (OR = 3.50, 95% CI = 1.92 - 6.40, P < 0.001). Meanwhile, other variables were not significantly associated (Table 4).

Abbreviations: OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence interval; Ref, reference group.

a P < 0.05.

b P < 0.001.

5. Discussion

This study highlights the substantial burden of depression and suicide risk among older adults with NCDs in Thailand, consistent with global trends of accelerated population aging and increasing multimorbidity (1, 2). The prevalence of depression (35.3%) and suicide risk (12.8%) aligns with previous studies reporting high psychological distress in this population (11-17). Importantly, our findings contribute region-specific insights, showing that the prevalence of depression in this Thai cohort is nearly double the global estimate from a recent meta-analysis, which reported a pooled prevalence of 19.2% (95% CI: 13.0 - 27.5%) (22). Older adults with NCDs often face progressive physical decline, emotional strain, and social isolation, compounded by long-term treatment demands and caregiver dependence. These factors contribute to anxiety, stress, low self-worth, and hopelessness — core drivers of depression and suicidal ideation (23).

Bunloet (24) similarly reported a 36.9% prevalence of depression, while Jaihan (25) highlighted higher rates among females and those with diabetes or hypertension. Our subgroup analysis extends this evidence, showing that female sex, advanced age (≥ 70 years), multiple comorbidities, prolonged illness, mobility limitations, daily activity difficulties, and poor mental self-care significantly elevate depression risk. Notably, poor self-care was the strongest determinant (OR = 6.08), echoing findings by Tupanich et al. (26), who reported that psychological well-being protects older adults against depression. This can be explained by the fact that low mental self-care weakens coping capacity and increases vulnerability to depression and suicide, while strong self-care enhances resilience and prevention. Similarly, studies (27, 28) highlight that low self-efficacy or poor self-care increases vulnerability, underscoring the importance of strengthening coping strategies, social support, and resilience to improve mental health outcomes. Na-Wichian et al. (29) also emphasized its close link with quality of life, reinforcing the need to embed self-care and resilience-building within chronic disease care.

Suicide risk showed parallel patterns, being significantly higher among individuals with an illness duration of 10 years or more, mobility limitations, comorbid anxiety/depression, and poor mental self-care. These findings illustrate how cumulative disease burden, physical impairment, and psychosocial distress converge to heighten suicidal ideation (7, 8). Koo et al. (30) observed that somatic disease burden among individuals who died by suicide increases with age, while Khamseeon et al. (31) and Juntapim (32) reported that family conflict and social withdrawal further exacerbate vulnerability. Our findings highlight poor self-care as a particularly strong predictor (OR = 3.50), underscoring the urgent need for interventions enhancing coping skills, resilience, and access to psychosocial support.

This study is limited by its geographic focus on the Nakhon Chai Burin region, which restricts the generalizability of the findings to other Thai regions with diverse socioeconomic and healthcare contexts. Demographic variables such as sex, marital status, and income were not significant for suicide risk, suggesting that disease-related and psychosocial factors exert stronger effects. Future research should adopt multi-regional or longitudinal designs to strengthen external validity. Additionally, integrating routine mental health screening into primary care, strengthening social support systems, and tailoring interventions for high-risk groups, particularly those with functional limitations, prolonged illness, or poor self-care, could mitigate the dual burden of depression and suicide risk in older adults.

5.1. Conclusions

About one-third of older adults with NCDs experienced depression, and one in nine were at risk of suicide, with a higher prevalence among women and those with mobility limitations. These findings highlight the urgent need for prevention and care strategies tailored to this population. Further research should examine longitudinal patterns and evaluate interventions to strengthen evidence-based policy and practice.