1. Background

Chronic migraine is defined as more than fifteen migraine headache days per month. Epidemiological research indicates that the prevalence of headaches in children varies widely, ranging from 5.9% to 82% (1). The International Headache Society (IHS) criteria are the most important diagnostic tools for primary headaches (2, 3). While these criteria have some limitations when applied to younger children, the latest version (ICHD-3) incorporates specific characteristics of migraine in children, such as shorter pain duration and bilateral or unilateral pain location (4, 5). Regarding therapeutic approaches for pediatric migraine, there is a paucity of clinical research on both acute and prophylactic treatments (6). This is partly attributed to variations in treatment methods influenced by political and cultural factors across different countries (7). Clinical trials in children are few and often yield conflicting results (5). While valuable, the placebo effect can paradoxically act as a barrier in controlled trials comparing non-pharmacological and pharmacological therapies against a placebo (8, 9). The primary goal of migraine prophylaxis is to reduce the impact of migraine by decreasing the intensity and frequency of attacks (10). In children and adolescents, prophylaxis is generally considered when attacks occur more than four times per month or when symptomatic treatment provides unsatisfactory relief (9). Pediatric migraine causes substantial disability and school absence, and preventive treatment is recommended for children with frequent or disabling attacks. Recent systematic reviews and meta-analyses summarize a heterogeneous evidence base for preventive medications in children and adolescents, with propranolol among the most commonly used agents but with mixed results across randomized trials and high placebo responses in pediatric populations (11, 12). At the same time, nutritional approaches, including B-vitamin supplementation such as pyridoxine (vitamin B6), have shown promising but inconsistent effects in adults and small pediatric series, and systematic reviews highlight the need for better-powered trials in children (13, 14). Although propranolol is commonly used for pediatric migraine prophylaxis, evidence from randomized trials is limited and responses are variable, with notable placebo effects. Pyridoxine (vitamin B6) has been only preliminarily studied, and its comparative efficacy against established drugs remains unclear.

2. Objectives

This study therefore aimed to compare the efficacy and safety of pyridoxine and propranolol in children, providing insight into potential low-risk alternatives for migraine prevention.

3. Methods

3.1. Study Setting and Population

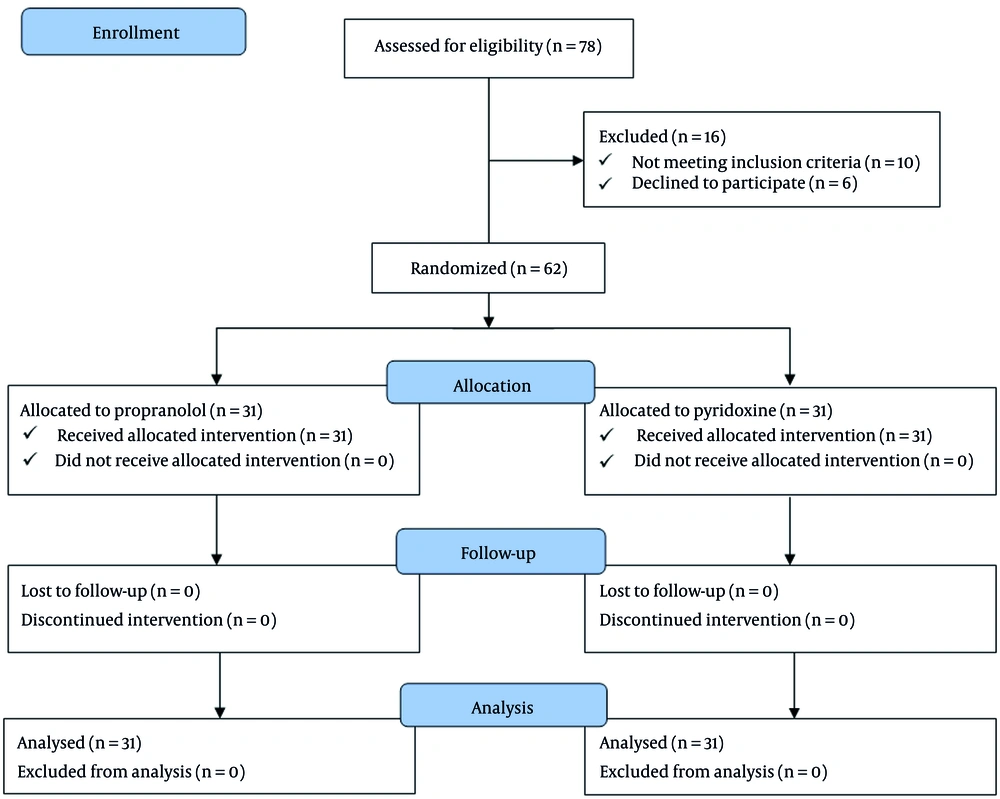

This prospective clinical trial was conducted at Amir Kabir Hospital in Arak, Iran. The study enrolled pediatric patients diagnosed with migraine headaches. The sample size was calculated to detect a clinically meaningful difference in headache duration and Ped MIDAS scores between the propranolol and pyridoxine groups. Assuming a two-sided significance level of α = 0.05, 80% power (β = 0.20), and a moderate effect size (Cohen’s d ≈ 0.7), the required sample size was 28 participants per group. To allow for potential dropouts, 31 participants were enrolled in each group. This sample size ensures adequate power to detect differences in the primary outcomes. A total of 62 pediatric participants were required for the study. However, 10 potential participants were excluded based on the exclusion criteria, and 6 declined to participate. Consequently, 78 cases were initially assessed, and 62 participants (31 in each treatment group) were ultimately enrolled and followed up in the study (Figure 1).

3.2. Randomization and Allocation Concealment

Participants were randomly assigned to treatment groups in a 1:1 ratio using a computer-generated random number sequence created by an independent statistician who was not involved in participant recruitment or assessment. Allocation codes were placed in sequentially numbered, opaque, sealed envelopes to ensure concealment. Also, the present study employed a double-blind design. Both participants and the investigator responsible for outcome assessment were blinded to group assignments. To maintain blinding, study medications were provided in identical-appearing containers, and instructions were standardized to prevent unblinding. All clinical evaluations and Ped-MIDAS questionnaire scoring were conducted by a blinded investigator.

3.3. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

3.3.1. Inclusion Criteria

- Pediatric patients diagnosed with migraine headaches.

- Definitive diagnosis of migraine by a pediatric neurologist according to International Classification of Headache Disorders, 3rd edition (ICHD-3) criteria.

- Exclusion of other potential etiologies for headaches.

- Age between 7 and 17 years.

- Informed consent obtained from both patient (if age-appropriate) and their parents/legal guardians.

3.3.2. Exclusion Criteria

- Documented allergic reactions to either propranolol or pyridoxine based on previous exposure.

- Known contraindications to propranolol use.

- Presence of severe kidney or liver failure.

- Inability to correctly adhere to medication regimen, as assessed through parental reporting.

- Withdrawal of consent by patient or their parents/legal guardians at any point during the study.

3.4. Study Procedures

Participants were randomized to one of two groups: (1) Propranolol group (n = 31): 10 mg orally, three times daily; (2) pyridoxine group (n = 31): 40 mg orally, once daily.

Doses were selected based on pediatric migraine prophylaxis guidelines and prior studies. ECG monitoring was performed for all patients in the propranolol group, initially weekly and then monthly. Medications were prescribed by a pediatric neurologist, and parents received detailed instructions on administration and potential side effects.

3.5. Measurements and Outcome Assessment

Outcome measures were assessed at baseline and after three months: (1) Headache frequency: Number of migraine attacks per week; (2) headache duration: Average hours per attack; (3) headache-related disability: Assessed using the pediatric migraine disability assessment (Ped-MIDAS) questionnaire

The Persian version of the adult MIDAS instrument has documented validity in Iranian populations (Cronbach α ≈ 0.80; test-retest ρ = 0.54 - 0.71) (15). A preliminary forward/back translation of Ped-MIDAS was performed, and pilot testing in 20 children demonstrated acceptable internal consistency (Cronbach α = 0.83) and test-retest reliability (ICC = 0.79). Full construct validity remains to be formally established. Adverse events were monitored throughout the study. Participants experiencing complications were referred to appropriate specialists, with costs covered by the study team.

3.6. Ethical Considerations

This study protocol was reviewed and approved by the Research Ethics Board of Arak University of Medical Sciences. The research was conducted in compliance with ethical principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki. The study received ethical approval with code IR.ARAKMU.REC.1398.186 and was registered in the Iranian Registry of Clinical Trials (IRCT) under code IRCT20191104045328N2.

3.7. Statistical Analysis

Data were analyzed using SPSS version 19.0. Continuous variables are presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD) and categorical variables as counts and percentages. Independent samples t-tests were used to compare baseline continuous variables (age, Ped-MIDAS scores, headache frequency, and duration) between propranolol and pyridoxine groups to ensure baseline comparability. Paired t-tests assessed within-group changes in Ped-MIDAS scores, headache frequency, and headache duration from baseline to three months. Analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) was applied for between-group comparisons of post-treatment outcomes, adjusting for baseline values, age, and sex to control for potential confounding. Fisher’s exact test compared categorical variables, including sex distribution, adverse events, and disability severity categories, between treatment groups. Effect sizes (Cohen’s d) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were calculated to quantify the magnitude and precision of between-group differences. A two-sided P-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. This analytical approach allowed evaluation of both statistical significance and clinical relevance of treatment effects.

4. Results

4.1. Demographics and Baseline Characteristics

A total of 62 pediatric participants were included, with 31 in each treatment group. The mean age of participants was 9.80 ± 2.47 years (propranolol: 9.71 ± 2.41; Pyridoxine: 9.90 ± 2.53; P = 0.954). Gender distribution was comparable between groups (propranolol: 19 males [61.29%], 12 females [38.71%]; Pyridoxine: 18 males [58.06%], 13 females [41.94%]; P = 0.817) (Table 1).

| Variables | Propranolol (n = 31) | Pyridoxine (n = 31) | Total (N = 62) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 9.71 ± 2.41 | 9.90 ± 2.53 | 9.80 ± 2.47 |

| Male | 19 (61.29) | 18 (58.06) | 37 (59.67) |

| Female | 12 (38.71) | 13 (41.94) | 25 (40.33) |

a Values are presented as No. (%) or mean ± SD.

b Tests used: Independent samples t-test for age

c Fisher’s exact test for sex distribution.

4.2. Primary Outcomes

4.2.1. Pediatric Migraine Disability Assessment Scores

Baseline Ped-MIDAS scores were similar between propranolol and pyridoxine groups (33.03 ± 6.11 vs. 33.26 ± 5.83; P = 0.963). After three months, both groups showed significant reductions (propranolol: 20.35 ± 8.89; pyridoxine: 20.58 ± 8.94; P < 0.001 for within-group change). ANCOVA-adjusted analyses, controlling for baseline Ped-MIDAS score, age, and sex, confirmed significant improvements in both groups (P < 0.001), with no statistically significant difference between groups post-treatment (P = 0.921). Between-group effect size was negligible (Cohen’s d = -0.026; 95% CI: -0.524, 0.472), confirming comparable efficacy (Table 2).

| Variables and Group | Before | After | P-Value (Within) | Between-Group Comparison, Adjusted by ANCOVA | Cohen’s d (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ped-MIDAS | 0.921 | -0.026 (-0.524, 0.472) | |||

| Propranolol | 33.03 ± 6.11 | 20.35 ± 8.89 | < 0.001 | ||

| Pyridoxine | 33.26 ± 5.83 | 20.58 ± 8.94 | < 0.001 | ||

| Headache Duration (hrs) | 0.932 | 0.020 (-0.478, 0.518) | |||

| Propranolol | 6.03 ± 0.95 | 3.03 ± 1.44 | < 0.001 | ||

| Pyridoxine | 6.10 ± 0.91 | 3.00 ± 1.55 | < 0.001 | ||

| Headache frequency (per week) | 0.743 | -0.087 (-0.585, 0.412) | |||

| Propranolol | 4.42 ± 0.85 | 1.87 ± 1.17 | < 0.001 | ||

| Pyridoxine | 4.55 ± 0.77 | 1.97 ± 1.14 | < 0.001 |

Abbreviation: Ped-MIDAS, pediatric migraine disability assessment.

a Values are presented mean ± SD.

b Tests used: Paired t-tests for within-group comparisons (baseline vs. 3 months); ANCOVA for between-group post-treatment comparisons adjusting for baseline values, age, and sex.

4.2.2. Headache Duration

Mean baseline duration was similar (propranolol: 6.03 ± 0.95 hours; pyridoxine: 6.10 ± 0.91 hours; P = 0.954). Both groups experienced significant reductions after treatment (propranolol: 3.03 ± 1.44 hours; pyridoxine: 3.00 ± 1.55 hours; P < 0.001). ANCOVA-adjusted comparisons showed no significant difference between groups (P = 0.932) with Cohen’s d = 0.020 (95% CI: -0.478, 0.518) (Table 2).

4.2.3. Headache Frequency

Baseline weekly attacks were comparable (propranolol: 4.42 ± 0.85; pyridoxine: 4.55 ± 0.77; P = 0.895). After treatment, both groups experienced significant reductions (propranolol: 1.87 ± 1.17; pyridoxine: 1.97 ± 1.14; P < 0.001). No significant difference was observed between groups after ANCOVA adjustment (P = 0.743), and effect size was negligible (Cohen’s d = -0.087; 95% CI: -0.585, 0.412) (Table 2).

4.2.4. Disability Severity

At baseline, most participants had moderate disability (propranolol: 70.97%; pyridoxine: 67.74%). After three months, there was a shift toward milder disability in both groups: (1) propranolol: Very mild 25.81%, mild 48.39%, moderate 25.81%; (2) pyridoxine: Very mild 29.03%, mild 48.39%, Moderate 22.58% (Table 3).

| Disability Severity and Group | Before | After |

|---|---|---|

| Very mild | ||

| Propranolol | 0 (0) | 8 (25.81) |

| Pyridoxine | 0 (0) | 9 (29.03) |

| Mild | ||

| Propranolol | 9 (29.03) | 15 (48.39) |

| Pyridoxine | 10 (32.26) | 15 (48.39) |

| Moderate | ||

| Propranolol | 22 (70.97) | 8 (25.81) |

| Pyridoxine | 21 (67.74) | 7 (22.58) |

a Values are presented as No. (%).

b Tests used: Fisher’s exact test for categorical comparisons; paired analyses for within-group change in disability categories.

4.3. Secondary/Subgroup Analyses

4.3.1. Age-Stratified Outcomes

Participants were stratified into 7 - 12 years (n = 33) and 13 - 17 years (n = 29). Both age groups showed significant reductions in Ped-MIDAS scores, headache duration, and frequency after treatment (P < 0.001 within each age group). ANCOVA-adjusted comparisons revealed no significant differences between age groups for any outcome (Ped-MIDAS: P = 0.546; duration: P = 0.560; frequency: P = 0.654). Effect sizes for between-age comparisons ranged from -1.26 to -0.36, with confidence intervals crossing zero, indicating similar responses across age groups (Table 4).

| Variables and Age Group | n | Before | After | P value (Within) | Between-Group Comparison, Adjusted by ANCOVA | Cohen’s d (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ped-MIDAS | 0.546 | - 0.359 (- 0.829, 0.111) | ||||

| 7 - 12 | 33 | 33.12 ± 5.22 | 18.85 ± 8.74 | < 0.001 | ||

| 13 - 17 | 29 | 33.15 ± 5.65 | 21.87 ± 8.85 | < 0.001 | ||

| Headache duration (hrs) | 0.560 | - 0.628 (- 1.125, - 0.131) | ||||

| 7 - 12 | 33 | 6.06 ± 0.94 | 2.54 ± 1.48 | < 0.001 | ||

| 13 - 17 | 29 | 6.08 ± 0.92 | 3.45 ± 1.56 | < 0.001 | ||

| Headache frequency (per week) | 0.654 | - 1.26 (- 1.79, - 0.73) | ||||

| 7 - 12 | 33 | 4.45 ± 0.86 | 1.12 ± 1.11 | < 0.001 | ||

| 13 - 17 | 29 | 4.54 ± 0.80 | 2.50 ± 1.13 | < 0.001 |

Abbreviation: Ped-MIDAS, pediatric migraine disability assessment.

a Tests used: Paired t-tests for within-age group comparisons; ANCOVA for between-age group comparisons adjusting for baseline values.

4.3.2. Sex-Stratified Outcomes

Both males and females exhibited significant improvements in all primary outcomes (P < 0.001). Post-treatment ANCOVA-adjusted comparisons demonstrated no significant sex-related differences (Ped-MIDAS: P = 0.812; duration: P = 0.779; frequency: P = 0.841) (Table 4).

4.3.3. Adverse Events

Both treatments were generally well tolerated. Mild adverse events were observed in 3 participants in the propranolol group (fatigue 2, bradycardia 1) and 1 participant in the pyridoxine group (gastrointestinal discomfort). No serious adverse events occurred, and no participants discontinued treatment due to side effects. Fisher’s exact test indicated no statistically significant difference in adverse events between the groups (P = 0.301) (Table 5).

| Group | Participants (n) | Fatigue | Bradycardia | GI Discomfort | Any AE | P value (Fisher) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Propranolol | 31 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 3 | 0.301 |

| Pyridoxine | 31 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

a Tests used: Fisher’s exact test to compare frequency of adverse events between treatment groups.

5. Discussion

Migraine attacks are a common neurologic condition in pediatric populations, affecting approximately 5 - 10% of adolescents. Severe migraine headaches can substantially reduce quality of life, leading to school absenteeism in up to 30% of affected children (15). Migraines are often misattributed to other causes such as attention-related behaviors, sinusitis, or refractive errors (8). Prevalence increases in adolescence, with a notable shift from male to female predominance (5). The mean age of migraine onset is 7 years in females and 10.9 years in males. Migraines are characterized by recurrent, throbbing, temporal or frontal headaches, often accompanied by nausea, lasting several hours (8). Preventive treatment should be considered in pediatric patients experiencing two or more attacks per month, intolerable or disabling headaches, hemiplegic migraine, inadequate response to acute therapy, or long-term aura (16). Conventional prophylactic agents include calcium channel blockers, antiepileptic drugs, and antidepressants/adrenergic inhibitors (15).

In this study, we directly compared propranolol and pyridoxine for migraine prophylaxis in children. Our results demonstrate that both interventions significantly reduced Ped-MIDAS scores, headache duration, and headache frequency, confirming their clinical efficacy. Importantly, after adjustment for baseline values, age, and sex using ANCOVA, no statistically significant differences were observed between the two treatment groups, suggesting comparable effectiveness.

Compared with previous studies, our findings align with earlier reports on propranolol’s efficacy. For instance, in another studt first reported propranolol effectiveness in pediatric migraine prophylaxis in 1966, while antiepileptic drugs such as carbamazepine were introduced in the 1970s (17). Similarly, Bali et al. observed reductions in monthly headache frequency with pregabalin and propranolol, consistent with our findings (8). However, unlike most prior studies, our trial demonstrates that pyridoxine provides comparable prophylactic efficacy, which has been less extensively studied in pediatric populations. This highlights a potential safe and accessible alternative to conventional pharmacologic treatments.

Nutraceutical interventions are gaining support. A 2024 review reported that pyridoxine (80 mg/day over 12 weeks) significantly reduced headache severity and duration (14), consistent with our findings in a pediatric population. These results indicate that pyridoxine is a viable, low-risk alternative for children who may be unable to tolerate conventional drugs.

In comparing effect sizes, our study observed reductions in Ped-MIDAS scores and headache frequency similar to those reported in one study (propranolol: 69%, sodium valproate: 72%) (14). However, unlike Hajhashemy et al. (14), we included pyridoxine as a comparator, demonstrating equivalent benefit and expanding the scope of prophylactic options. This direct head-to-head comparison strengthens the evidence for pyridoxine’s role in pediatric migraine prevention.

While other prophylactic agents, such as cyproheptadine, amitriptyline, topiramate, gabapentin, and levetiracetam, have demonstrated efficacy in pediatric and adolescent populations (18-20), our study uniquely contextualizes these findings by comparing a pharmacologic agent (propranolol) with a vitamin-based approach (pyridoxine), providing insight into both efficacy and tolerability for clinical decision-making.

Notably, the safety profile in our study was acceptable, with only mild adverse events reported in a few participants, and no serious adverse events observed. This reinforces the potential clinical utility of both propranolol and pyridoxine as well-tolerated options for pediatric migraine prophylaxis and supports their consideration in cases where conventional medications may be contraindicated or poorly tolerated.

From a health policy perspective, our results have practical relevance: Pyridoxine, as a low-cost and safe alternative, could be considered in pediatric migraine management guidelines, particularly in resource-limited settings. Broader adoption of such interventions may reduce school absenteeism, improve quality of life, and decrease societal costs associated with pediatric migraine.

From a clinical perspective, these findings provide practical guidance for individualized treatment selection: Pyridoxine may be preferred in children with asthma, bradycardia, or other contraindications to β-blockers, and it may also be advantageous in resource-limited settings due to low cost and minimal monitoring requirements. Conversely, propranolol may be favored when a more rapid clinical response is desired and adequate cardiovascular monitoring is available.

Strengths of this study include its randomized design, use of ANCOVA to control for confounding, and inclusion of age- and sex-stratified analyses. The direct comparison of propranolol and pyridoxine provides novel insight into comparative efficacy. Limitations include the relatively short follow-up period, moderate sample size, lack of placebo control, partial blinding, and limited psychometric validation of the Persian Ped-MIDAS instrument. These factors may restrict generalizability and limit detection of long-term or subtle differences. Future research should evaluate different pyridoxine dosages, explore combined nutraceutical-pharmacologic strategies, and investigate long-term safety and efficacy over extended follow-up periods. Larger multicenter studies and analyses of specific subgroups, such as different age ranges, comorbid conditions, or migraine phenotypes, are warranted to refine treatment guidelines and clarify pyridoxine’s role in pediatric migraine prophylaxis.

5.1. Conclusion

This study demonstrates that both pyridoxine and propranolol are effective and well-tolerated options for prophylactic management of pediatric migraine, significantly reducing headache frequency, duration, and disability as measured by Ped-MIDAS. No significant differences were observed between the two treatment groups, indicating comparable efficacy. Clinically, pyridoxine provides a safe, low-cost alternative for children who cannot tolerate conventional pharmacologic therapy, offering flexibility for individualized treatment decisions. Future research should focus on evaluating optimal pyridoxine dosing ranges, assessing the long-term safety and durability of treatment effects over extended follow-up periods, and exploring combined nutraceutical-pharmacologic strategies that may offer synergistic benefit. Additionally, larger multicenter trials and analyses across specific subgroups — such as different age ranges, comorbid conditions, or migraine phenotypes — are warranted to refine treatment algorithms and further clarify pyridoxine’s role in pediatric migraine prophylaxis.