1. Background

Multiple sclerosis (MS) is a chronic, immune-mediated disease of the central nervous system and a leading cause of non-traumatic neurological disability in young adults. Recent global surveillance indicates a rising burden, with an estimated 2.8 - 2.9 million people now living with MS worldwide; this upward trend across regions underscores the need for scalable, patient-centered interventions that target outcomes beyond motor impairment, including quality of life (QoL) (1).

QoL in people with MS is multidimensional, spanning physical functioning, vitality/fatigue, psychological well-being, sleep, and role/social participation, and is consistently lower than in the general population. In Middle Eastern health systems, including Iran, limited access to comprehensive neuropsychological and rehabilitative services may widen these QoL gaps and amplify day-to-day disease burden. When headache is a prominent comorbidity, the Headache Impact Test-6 (HIT-6) offers a brief, validated index of headache-related QoL/impact; higher scores indicate worse impact. The Persian HIT-6 has shown acceptable reliability and validity, supporting its use in Iranian cohorts (2).

Progressive muscle relaxation (PMR) is a structured behavioral technique involving systematic tension–release of major muscle groups with diaphragmatic breathing. Grounded in the biopsychosocial model, which integrates biological, psychological, and social determinants of illness experience, PMR aims to reduce somatic hypervigilance and sympathetic arousal, enhance autonomic balance, and improve sleep and affect regulation (3, 4). PMR is inexpensive, equipment-free, culturally adaptable, and deliverable by nurses with home-practice reinforcement. Contemporary consensus in headache care recognizes relaxation-based therapies (including PMR) as effective adjuncts that can improve patient-reported outcomes (5). Evidence from randomized and pragmatic trials in primary headache populations, including smartphone-delivered PMR, demonstrates clinically meaningful improvements and supports feasibility and scalability (6). Early nursing-led studies in MS populations further suggest benefits of relaxation training for stress and related symptoms, and at least one quasi-experimental study reported QoL gains with PMR in people with MS (7, 8).

Despite accumulating evidence for relaxation-based care in primary headache, controlled evaluations of nurse-delivered PMR that target headache-related QoL in people with MS using a validated instrument such as HIT-6 remain scarce in Middle Eastern settings. Prior MS studies have often focused on stress, fatigue, or general well-being rather than a headache-specific QoL endpoint; baseline-adjusted analyses are not consistently employed; and region-specific data remain limited. Our earlier regional report established the feasibility of a brief PMR program in people with MS within routine services but did not isolate HIT-6-defined QoL as the primary outcome (9). Filling this gap would yield implementation-ready evidence for nurse-led, low-cost strategies to enhance QoL in MS clinics.

2. Objectives

We conducted a quasi-experimental, parallel-group evaluation of a six-week PMR program (three supervised sessions plus daily home practice) delivered by nurses in Zahedan, Iran. We hypothesized that, compared with usual care, PMR would produce significantly lower follow-up HIT-6 scores (better headache-related QoL) after adjustment for baseline HIT-6 and disease duration.

3. Methods

3.1. Study Design

We conducted a controlled quasi-experimental study with a pretest–posttest design and a parallel control group. Participants were recruited through consecutive convenience sampling from the Zahedan MS Society and affiliated neurology clinics.

3.2. Sampling and Allocation and Blinding

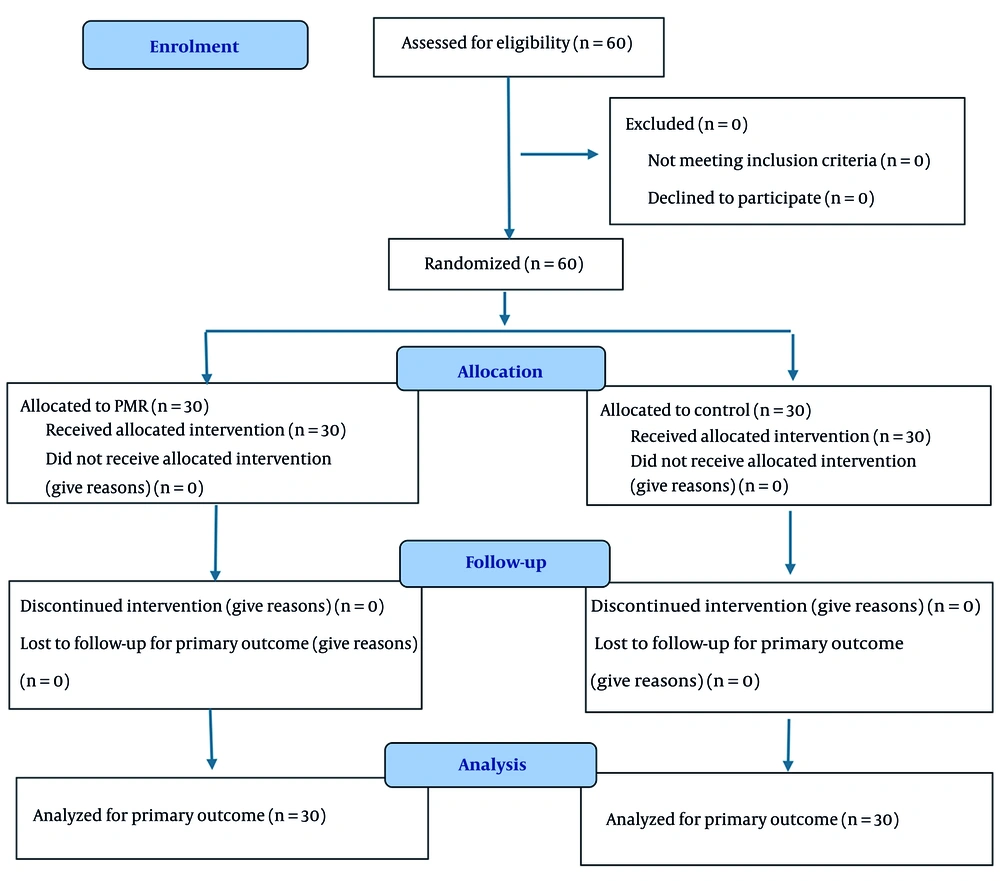

After confirming eligibility and completing baseline assessments, enrolled individuals were randomly allocated (1:1) to the PMR intervention or usual care using a computer-generated random sequence and sequentially numbered, opaque, sealed envelopes (SNOSE) prepared by an independent researcher. Given the behavioral nature of the intervention, blinding of participants and facilitators was not feasible; outcomes (primary outcome: HIT-6) were self-reported at baseline and at the 3-month follow-up. To minimize analytical bias, group codes were masked to the data analyst until the primary analyses were completed. Although random allocation was implemented, we classify this study as controlled quasi-experimental rather than a registered clinical trial due to the use of convenience sampling, the absence of prospective trial registration, and the infeasibility of participant/facilitator blinding. Where applicable, we adhered to CONSORT-aligned reporting (Figure 1).

3.3. Setting and Study Period

The study was conducted at the Zahedan MS Society and neurology clinics across Zahedan, Iran, in 2023 (May - August 2023).

3.4. Population and Sampling

The study population included all patients with neurologist-confirmed MS who were members of the Zahedan MS Society or attended collaborating neurology clinics in Zahedan during the study period. Using consecutive convenience sampling, potentially eligible adults were approached and enrolled until the target sample size (N = 60) was reached. Eligible participants were ≥ 18 years old, had a definite MS diagnosis, reported recurrent headaches, and provided written informed consent. Individuals were excluded if they had a substance use disorder or an active psychiatric condition that could interfere with the intervention or outcome assessment. Participants were withdrawn post-enrollment if they withdrew consent, missed ≥ 1 PMR training session, were unable to perform or maintain the technique for two consecutive days, experienced an MS relapse or clinical deterioration during follow-up, or initiated any new headache-specific intervention (behavioral, educational, rehabilitative, or similar) during the study.

3.5. Sample Size

The required sample size was calculated using a two-sample means formula for quasi-experimental designs. Given the lack of prior data on HIT-6 in MS, we assumed an effect size of d = 0.80 based on a similar study of PMR’s impact on pain-related disability (9). The following values were used: A two‑sided significance level (α) of 0.05 (Z₁‑α/₂ = 1.96), statistical power of 80% (β = 0.20, Z₁‑β = 0.84), and an effect size (d) of 0.80. Applying these values yielded a requirement of 25 participants per group. To account for an anticipated attrition rate of 15%, the sample size was adjusted to 30 participants per group, resulting in a total sample of 60 participants.

3.6. Participant Information and Consent

All participants received oral and written information about the study’s aims, procedures, potential benefits/risks, the voluntary nature of participation, data confidentiality, and their right to withdraw at any time without penalty. Those agreeing to participate provided written informed consent. Before any allocation or intervention, participants in both groups completed a demographic/clinical information form and the HIT-6 questionnaire.

3.7. Intervention

Participants in the PMR group (accompanied by a family caregiver) received three nurse-led group training sessions of 20 - 30 minutes on three consecutive days. In these sessions, they were taught Jacobson’s PMR technique under standardized conditions (quiet room, dim lighting, semi-sitting posture, comfortable clothing). The PMR protocol involved guided tension–release exercises across 14 muscle groups (forehead, eyes, jaw, lips; neck; fingers and palms; forearms; upper arms; shoulders; upper back; lower back; chest; abdomen; buttocks; thighs; calves; feet), paired with diaphragmatic breathing. Participants were instructed to inhale (~4 seconds) while tensing each muscle group (~5 seconds), then exhale (~6 seconds) and relax (~10 seconds) before moving to the next group (7). Each session concluded with whole-body relaxation and several deep breaths. Session 1 included brief education on MS, primary and chronic headaches, and an introduction to PMR. Session 2 followed the scripted PMR sequence with supervised practice. Session 3 emphasized reinforcement, Q&A, and troubleshooting. After the training, participants were instructed to practice PMR at home for 20 minutes daily over the next 6 weeks. Adherence was supported through weekly telephone follow-up calls, and participants received a Persian-language booklet and an audio CD to guide home practice. Because training took place in the presence of a caregiver, family members were encouraged to prompt and supervise the patient’s daily practice using a provided checklist. The control group received usual care during the study period (standard medical management and any existing supportive therapies, but no PMR training). For ethical reasons, after the 3-month follow-up was completed, control group participants were offered the PMR educational materials.

3.8. Follow-up Assessments

The post-intervention assessment at 3 months consisted of repeating the HIT-6 questionnaire in both groups. No participants were lost to follow-up for the primary outcome.

3.9. Instruments and Outcome Measures

Introducing HIT-6: The HIT-6 is a brief, condition-specific instrument for assessing the impact of headaches on QoL and daily functioning. It contains 6 items covering pain severity, role/social functioning, fatigue, cognition, and mood effects of headaches. Each item has five frequency-based response options scored as follows: Never = 6, Rarely = 8, Sometimes = 10, Very Often = 11, Always = 13. The total HIT-6 score is the sum of item scores, ranging from 36 to 78, with higher scores indicating greater headache impact and worse QoL (10, 11). The Persian version of HIT-6 was validated by Zandifar et al. (2) in migraine and tension-type headache patients, demonstrating acceptable psychometric properties. In their evaluation, internal consistency (Cronbach’s α) was approximately 0.74 and test-retest reliability showed a moderate correlation (r ~0.50); convergent validity with the SF-36 QoL subscales was acceptable (2). In this study, baseline assessments included the demographic/clinical form and the HIT-6. The PMR intervention was then delivered as described, while the control group continued with usual care. Follow-up at 3 months involved re-administering the HIT-6. All questionnaire responses were confidential, and participants were reminded that they could withdraw at any time.

3.10. Statistical Analysis

Data were analyzed using SPSS version 24. Descriptive statistics (mean, standard deviation for continuous variables; frequency, percentage for categorical variables) were used to summarize sample characteristics and outcomes. The Shapiro–Wilk test was used to examine normality of continuous data, and Levene’s test was used to assess homogeneity of variance. Between-group comparisons at baseline were performed using independent-samples t-tests for continuous variables and χ² tests for categorical variables. The primary analysis compared post-intervention HIT-6 scores between groups using analysis of covariance (ANCOVA), with baseline HIT-6 score and MS duration entered as covariates. ANCOVA diagnostics (normality of residuals, homogeneity of variances, homogeneity of regression slopes, and linearity) are summarized in Appendix 1, in the Supplementary File. Effect size was reported as partial eta-squared (η²), interpreted as ~0.01 small, 0.06 medium, and 0.14 large. We report Adjusted Mean Difference (AMD) with 95% CI. Two-sided α = 0.05 (10-12). For clinical interpretability, we referenced the minimally important difference (MCID) for the HIT-6, commonly cited as ≥ 3 points in primary-care headache populations. We compared our AMD against this threshold (13).

3.11. Trial Transparency and Ethics

The study received ethics approval (IR.ZAUMS.REC.1402.439). We appreciate the request for clarity regarding trial registration. During proposal review, our institutional committee determined that the project does not constitute a clinical trial because recruitment used consecutive convenience sampling and random allocation SNOSE was applied only after recruitment to balance groups, rather than implementing random sampling with prospective trial registration.

4. Results

4.1. Participants

Sixty participants were enrolled and analyzed (PMR = 30; Control = 30). Table 1 summarizes baseline characteristics. Groups did not differ in age (35.2 ± 6.4 vs 31.9 ± 6.6 years; P = 0.057) or sex distribution (female: 83.3% vs 73.3%; P = 0.531). The PMR group had a longer MS duration (7.0 ± 4.3 vs 4.4 ± 3.4 years; P = 0.014). Baseline headache impact HIT-6 was similar (58.2 ± 9.9 vs 59.5 ± 6.1; P = 0.552).

| Variables | PMR (n = 30) | Control (n = 30) | Test Statistic | P-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (y) | 35.2 ± 6.4 | 31.9 ± 6.6 | t = 1.94 | 0.057 |

| Gender | χ² = 0.39 | 0.531 | ||

| Female | 25 (83.3) | 22 (73.3) | ||

| Male | 5 (16.7) | 8 (26.7) | - | - |

| MS duration (y) | 7.0 ± 4.3 | 4.4 ± 3.4 | t = 2.54 | 0.014 |

| HIT-6 (baseline) | 58.2 ± 9.9 | 59.5 ± 6.1 | t = 0.60 | 0.552 |

Abbreviation: PMR, progressive muscle relaxation; HIT-6, the Headache Impact Test-6.

a Values are expressed as Mean ± SD or No. (%).

bContinuous: Independent-samples t-test. Categorical: χ² test. Means ± SD to 1 decimal; P-values to 3 decimals.

4.2. Unadjusted Outcomes

At 3 months, mean HIT-6 decreased in PMR (58.2 → 56.0) and increased in Control (59.5 → 62.0). The between-group difference at 3 months was significant (unadjusted difference = -6.0; P = 0.002). Within-group changes did not reach significance (PMR: -2.3, P = 0.330; Control: +2.5, P = 0.070). See Table 2.

| Timepoint/Analysis | PMR | Control | Unadjusted Difference (PMR-Control) | P-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | 58.2 ± 9.9 | 59.5 ± 6.1 | -1.3 | 0.552 |

| 3 Months | 56.0 ± 8.9 | 62.0 ± 4.9 | -6.0 | 0.002 |

| Within-group change (3m - baseline) | -2.3 (PMR) | +2.5 (control) | - | PMR: 0.330; control: 0.070 |

Abbreviation: PMR, progressive muscle relaxation.

a Values are expressed mean ± SD.

b Between-group (each timepoint): t-test, unadjusted. Within-group: Paired t-test (descriptive; not for treatment inference). Lower HIT-6 indicates lower headache impact.

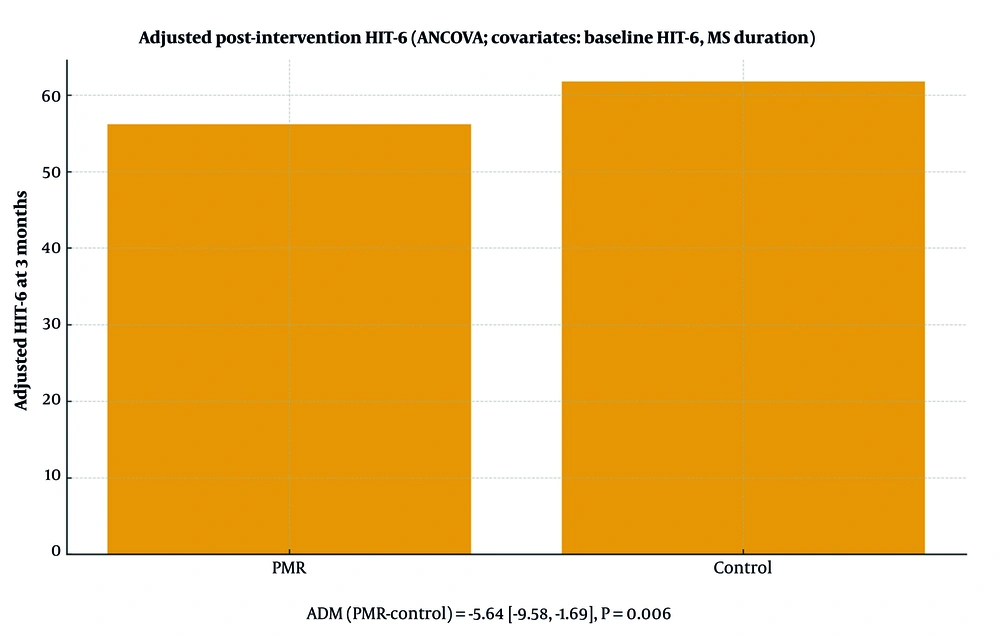

4.3. Adjusted Comparison (Primary Analysis)

In ANCOVA adjusting for baseline HIT-6 and MS duration, the group effect was significant (F = 8.20, P = 0.006; partial η² = 0.128). Adjusted means were 56.15 (PMR) vs 61.78 (Control), yielding AMD (PMR-Control) = -5.64 (95% CI -9.58 to -1.69; P = 0.006). In a sensitivity model (covariate: Baseline HIT-6 only), the result was consistent (AMD = -5.86; 95% CI -9.58 to -2.15; P = 0.003; partial η² = 0.149). Model assumptions (normality, homoscedasticity, linearity, homogeneity of regression slopes) were checked and met; conclusions were unchanged in complete-case analyses. Figure 2 presents adjusted group means with 95% CIs from the primary ANCOVA model (lower HIT-6 indicates better outcomes).

4.4. Interpretation

The adjusted between-group difference (~5.6 points on the 36 - 78 HIT-6 Scale) indicates a directionally favorable, clinically interpretable reduction in headache impact associated with PMR.

In the context of HIT-6 interpretability, between-group minimal important difference (MID) thresholds of approximately -1.5 (primary-care migraine) and ≈-2.3 have been reported, while within-person minimal important change (MIC) typically ranges -2.5 to -6 points and may be larger in chronic tension-type headache ≈-8 (13). Our adjusted effect—AMD (PMR-Control) = -5.64 (95% CI -9.58 to -1.69)—exceeds these MID thresholds, indicating a clinically interpretable reduction in headache impact associated with PMR at 3 months.

Adjusted mean HIT-6 at 3-month follow-up (ANCOVA adjusted for baseline HIT-6 and MS duration); error bars indicate 95% confidence intervals (lower scores = better) (Table 3).

| Model | Adjusted Mean (PMR) | Adjusted Mean (Control) | AMD | 95% CI for AMD | P-Value | Partial η² |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Primary ANCOVA (baseline HIT-6 + MS duration) | 56.15 | 61.78 | -5.64 | (-9.58, -1.69) | 0.006 | 0.128 |

| Sensitivity (baseline HIT-6 only) | - | - | -5.86 | (-9.58, -2.15) | 0.003 | 0.149 |

Abbreviation: AMD, Adjusted Mean Difference; HIT-6, the Headache Impact Test-6; MS, Multiple sclerosis.

a Covariates in primary model: Baseline HIT-6, MS duration.

5. Discussion

In adults with MS and recurrent headaches, a brief, nurse-delivered PMR program plus six weeks of home practice was associated with lower headache impact at 3 months versus usual care. The primary analysis (ANCOVA adjusted for baseline HIT-6 and MS duration) indicated a statistically significant difference between groups with a moderate effect magnitude.

After adjustment, the PMR group showed a lower HIT-6 than controls (AMD ≈ -5.64; 95% CI -9.58 to -1.69). The observed adjusted difference on HIT-6 (-5.64 points) is larger than commonly cited between-group MID thresholds (≈-1.5 to -2.3) and falls within or above reported within-person MIC ranges (-2.5 to -6), suggesting that the between-group effect is not only statistically significant but also clinically meaningful for patients’ daily functioning. This strengthens the practical relevance of the finding beyond P-values.

Ailani et al. (5) and other experts have advocated integrating behavioral therapies including relaxation training into routine headache care to improve patient-centered outcomes. Our findings align with these recommendations by demonstrating a measurable quality-of-life benefit with a low-risk behavioral adjunct in an MS population. In a controlled trial, Meyer et al. (12) showed that PMR reduced migraine burden and even normalized certain electrophysiological markers (contingent negative variation) associated with cortical excitability (12). Our results are consistent in direction and clinical benefit: Supervised PMR plus sustained home practice improved a patient-reported outcome (HIT-6) in the MS headache cohort. Any differences in magnitude likely reflect methodological and population differences: Meyer et al. (12) focused on migraine patients in a neurophysiology study, whereas we targeted a functional quality-of-life outcome (HIT-6) in an MS sample. Two pragmatic studies by Minen et al. (6, 14) – a randomized trial in primary care and a single-arm feasibility study – reported that smartphone-delivered PMR can reduce migraine-related disability and is feasible for outpatient use (6, 14). We observed a similar clinical signal using in-person delivery. Where our effect size appears comparatively large (in the context of behavioral trials), likely contributing factors include a clearly defined “dose” of the intervention (three supervised sessions plus six weeks of daily practice), active adherence support via weekly calls, and our choice of a quality-of-life outcome (HIT-6) that may be more sensitive to behavioral change than headache frequency alone. Systematic reviews of digital self-management for headaches (e.g., Chen and Luo) indicate heterogeneity in outcomes, with some trials showing modest or null between-group differences (15). Our moderate effect, relative to some digital interventions, likely reflects the structured format, adherence monitoring, and our focus on headache impact (which can capture improvements in coping and daily functioning even when headache frequency changes are small).

Turning to MS-specific literature, studies by Adamczyk et al., Souissi et al., and Gebhardt et al. have documented that headaches, especially migraine and tension-type, are common in MS and are intertwined with mood disturbances, autonomic dysregulation, and musculoskeletal tension. While those reports did not evaluate PMR, they support our rationale that behavioral approaches targeting muscle tension and arousal can be beneficial in this population (16-18). Our work extends this concept by providing controlled evidence that a relaxation intervention can improve a patient-reported quality-of-life metric in MS patients with headaches.

The PMR may act through convergent pathways—reducing skeletal muscle tension, attenuating autonomic arousal, normalizing breathing patterns, and enhancing self-regulatory confidence—consistent with biopsychosocial models of headache and central sensitization.

5.1. Strengths and Limitations

5.1.1. Strength

Strengths include a standardized, low-cost, nurse-led protocol; explicit dose (three supervised sessions plus structured home practice); high retention; and use of a validated, patient-reported outcome with baseline adjustment.

5.1.2. Limitations

First, the design was controlled quasi-experimental with convenience sampling and post-recruitment random allocation SNOSE to balance groups; therefore, causal inference is limited, and residual confounding cannot be excluded. Second, participant/facilitator blinding was not feasible for a behavioral intervention, which may introduce performance bias, although analyst masking was applied. Third, this was a single-center pilot with a modest sample size and short follow-up, limiting generalizability and precluding conclusions about durability of effects. Fourth, the project was not prospectively registered as a clinical trial, consistent with the institutional protocol-review determination that convenience sampling with post-recruitment allocation constitutes a quasi-experimental service evaluation rather than a clinical trial; nonetheless, non-registration is acknowledged as a methodological limitation. Fifth, outcomes relied on self-reported HIT-6, which is subject to reporting variance; objective headache diaries and longer follow-up should be incorporated in future work.

5.2. Implications for Practice and Research

The PMR appears feasible and scalable as an adjunct within multidisciplinary MS care. Larger, multicenter randomized trials with longer follow-up, blinded outcome assessment, objective adherence monitoring, and active control conditions are warranted. Subgroup analyses (e.g., migraine-like vs tension-type headache; MS subtypes) may refine targeting. Establishing an anchor-based MCID for HIT-6 specifically in MS would further strengthen clinical interpretability. Comparative-effectiveness and cost-effectiveness evaluations of PMR versus other behavioral options (e.g., mindfulness, biofeedback) are also indicated.

5.3. Conclusions

A brief, nurse-led PMR program, reinforced by structured home practice, was associated with a clinically interpretable reduction in headache impact (HIT-6) at three months versus usual care. Given its low cost, safety, and feasibility for routine nursing workflows, PMR is a pragmatic adjunct for MS services. Larger, multicenter randomized trials with longer follow-up and objective adherence tracking are warranted.