1. Background

Obesity, defined as excess body fat mass, has emerged as a global epidemic. High fructose consumption is associated with decreased resting energy expenditure, elevated blood lipid levels, impaired fat oxidation, insulin resistance, increased body fat percentage, and inflammation (1). The excessive intake of fatty and high-fructose foods is a principal driver of the current obesity epidemic and related metabolic disorders. Obesity and excessive fat accumulation result from an imbalance between energy intake and expenditure (2, 3). Obesity and increased adiposity are known risk factors for chronic diseases such as diabetes and cardiovascular diseases, which have become the leading causes of sudden death in recent years (4). In addition to genetic predisposition, disrupted lipid profiles and cardiovascular risk factors in obese (OB) individuals contribute to a higher susceptibility to cardiovascular diseases (5). Hormonal and metabolic disturbances, as well as alterations in signaling pathways, are critical for optimal cardiac function. Disruption of cardiac signaling pathways due to obesity or related conditions can result in heart failure, myocardial infarction, and pathological cardiac hypertrophy. Cardiac hypertrophy is recognized as an independent risk factor that significantly increases mortality associated with cardiovascular diseases (6).

Exercise (EX) training is widely recommended as a safe and effective non-pharmacological strategy to prevent cardiac diseases and even restore cardiac function. Understanding the molecular mechanisms underlying physiological cardiac adaptation to EX could reveal new therapeutic targets for cardiovascular dysfunction. Among these, the modulation of gene expression appears to be a powerful therapeutic approach. However, little is known about the regulatory networks among different gene classes or the mechanisms by which EX -induced gene modulation influences physiological cardiac remodeling. For instance, Liu et al. identified microRNA (miRNA) signatures in physiological cardiac hypertrophy induced by voluntary wheel running and ramp swimming models, while Fish et al. explored the role of miRNA-126 in cardiac angiogenesis following swimming training. The EX increased miRNA-126 expression and suppressed target genes involved in vessel growth (7, 8).

The mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) signaling pathway, comprising rapidly accelerated fibrosarcoma (RAF), mitogen-activated protein kinase (MEK: also MAP2K), and extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK), is integral to these processes (8, 9). Several studies have shown that intense EX can lead to increased left ventricular wall thickness and chamber size, considered pathological changes resulting from excessive training (10). Conversely, human and animal studies have identified the responsiveness of various signaling pathways to acute EX (11). Nevertheless, the effect of interval training on transcription factors involved in physiological cardiac hypertrophy, particularly the RAF, MEK, and ERK complex, has received less attention. Intermittent EX can elicit rapid physiological adaptations. Few studies have assessed the signaling pathway involving RAF, MEK, and ERK in cardiac hypertrophy, especially concerning obesity and aerobic EX (12).

2. Objectives

This study aimed to investigate the impact of obesity induction on RAF, MEK, and ERK gene expression and cardiac hypertrophy, as well as the potential of aerobic EX to prevent cardiac hypertrophy in a rat model of obesity induced by a high-fat/fructose diet.

3. Methods

3.1. Animals

Twenty-four Wistar rats were obtained from Ahvaz Jundishapur University of Medical Sciences, Iran, weighing 220 ± 14.1 g. The rats were randomly divided into three groups (n = 8 per group) based on previous studies (13, 14): Control, OB, and obese with aerobic exercise (OB+EX). Animals were housed in a controlled environment (25 ± 2°C, 50% humidity measured by hygrometer) with a 12/12-hour light/dark cycle and had free access to food and water. The OB groups received a high-fat/fructose diet, while the control group received standard chow (ethics code: IR.IAU.AHVAZ.REC.1402.025).

3.2. Induction of Obesity Model

Obesity was induced by administering a high-fat, high-fructose diet for eight weeks. This model is commonly used to simulate human obesity and to study metabolic disorders such as insulin resistance, fatty liver disease, and cardiovascular complications. The diet was provided continuously for eight weeks, a sufficient period to significantly alter body weight, fat mass, and metabolic parameters in rodents. High-fat pellets were sourced from Isfahan Royan Biotech Company. The ingredients consisted of 45 kg of standard pellet powder (composed of grains, vitamins, and minerals), 30 kg of animal fat (extracted from melted cow tail), and added soybean oil as a fat source. The final composition contained 60% fat, much higher than standard rodent chow (10 - 15% fat). Ingredients were thoroughly mixed and processed into pellets for consumption. The high-fat content increased caloric density, promoting weight gain.

A fructose solution was prepared by dissolving 250 mL of liquid fructose in 750 mL of water to yield 1 L of a 25% fructose solution, freshly prepared daily for stability and palatability and provided in 500 mL bottles ad libitum. This mimicked sugary beverage consumption in humans, promoting insulin resistance, hepatic steatosis, and visceral fat accumulation.

3.3. Aerobic Exercise Protocol

The aerobic EX protocol spanned eight weeks and was designed to achieve moderate to intense levels. The EX was progressively intensified using the principle of gradual overload, with incremental increases in speed and duration to enhance endurance and avoid overtraining. Training occurred daily from 16:00 to 18:00 (4:00 - 6:00 PM), corresponding to the end of the rats’ sleep cycle, given their nocturnal activity, to ensure consistency and maximize physiological response. Each week, speed, duration, or both were increased until week 5, after which intensity plateaued through week 8 to maintain a consistent training load. All variables remained unchanged during the eighth week to stabilize outcomes for final assessments (Table 1).

| Weeks | Speed (m/min) | Duration (min) |

|---|---|---|

| Week 1 | 10 | 10 |

| Week 2 | 10 | 20 |

| Week 3 | 14 - 15 | 20 |

| Week 4 | 14 - 15 | 30 |

| Week 5 - 8 | 17 - 18 | 30 |

3.4. Cardiac Hypertrophy Measurement

At the end of the experiment, rats were anesthetized with an intraperitoneal injection of xylazine (10 mg/kg) and ketamine (90 mg/kg). Hearts were excised and rinsed in physiological saline to remove blood, then blotted on filter paper to remove excess moisture before weighing on a digital scale accurate to 0.001 g. Cardiac hypertrophy was assessed using the ratios of heart weight to body weight and left ventricle weight to body weight.

3.5. Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay Measurement of Cardiac Hypertrophy Biomarkers

Following anesthesia, blood samples were collected and centrifuged. The supernatant was used to determine vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) and NAD-dependent deacetylase sirtuin-3 (SIRT3) concentrations as cardiac hypertrophy biomarkers, using manufacturer-supplied kits and following the provided protocols.

3.6. Real-time Polymerase Chain Reaction Analysis of Rapidly Accelerated Fibrosarcoma/MEK/Extracellular Signal-Regulated Kinase Gene Expression

After eight weeks of EX, cardiac tissue samples were collected post-anesthesia. Total RNA was extracted using the RNeasy Plus Mini Kit. Complementary DNA (cDNA) synthesis was performed using the Quantitate Reverse Transcriptase Kit. For the real-time PCR reaction, 1 mL of cDNA, reverse primers, 10 mL of master mix real-time, and RNase-free water were combined. Gene expression levels for RAF, MEK, and ERK were quantified relative to glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) as the control gene, using the real-time RT-PCR method.

3.7. Statistical Methods

Data analysis was performed using SPSS software (version 22). Group comparisons were conducted using one-way ANOVA with post hoc testing. Data are presented as mean ± SEM, with statistical significance defined as P < 0.05.

4. Results

4.1. Exercise Decreased Cardiac Hypertrophy Indices in Obese Rats

As shown in Figure 1, obesity significantly increased the ratios of heart weight/body weight and left ventricle weight/body weight, indicating cardiac hypertrophy compared to the control group. Eight weeks of EX significantly reduced these indices in OB rats compared to the OB group.

Comparison of Cardiac Hypertrophy indices: Heart/body weight (A) and left ventricle/body weight (B) among the control, obese (OB, high-fat/fructose diet), and obese with aerobic exercise [OB+EX, high-fat/fructose diet plus exercise (EX)] groups (data are presented as mean ± SEM; group comparisons were performed using one-way ANOVA and HSD; * P < 0.05 and ** P < 0.01 vs. control; # P < 0.05 vs. OB group).

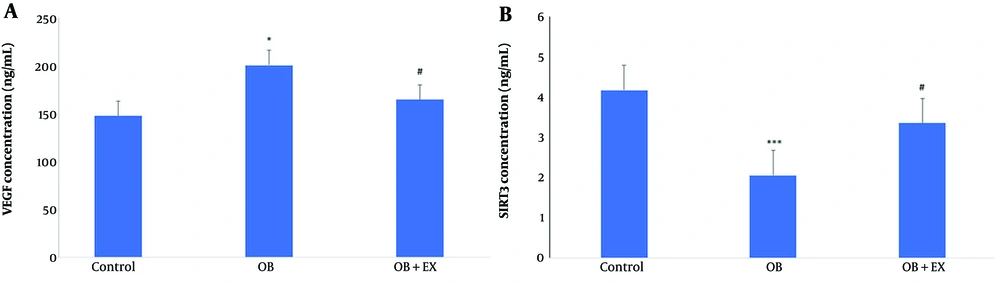

4.2. Exercise Improved Cardiac Hypertrophy Biomarkers in Obese Rats

As illustrated in Figure 2A, obesity significantly increased VEGF levels compared to controls, whereas eight weeks of EX significantly decreased VEGF in serum samples compared to the OB group. Conversely, NAD‐dependent deacetylase SIRT3 levels were significantly reduced in the OB group compared to controls, while eight weeks of EX increased SIRT3 levels relative to the OB group (Figure 2B).

Comparison of VEGF (A) and sirtuin-3 (SIRT3) (B) concentrations among the control, obese (OB), and obese with aerobic exercise (OB+EX) groups (data are presented as mean ± SEM; group comparisons were performed using one-way ANOVA and HSD; * P < 0.05 and *** P < 0.001 vs. control; # P < 0.05 vs. OB group).

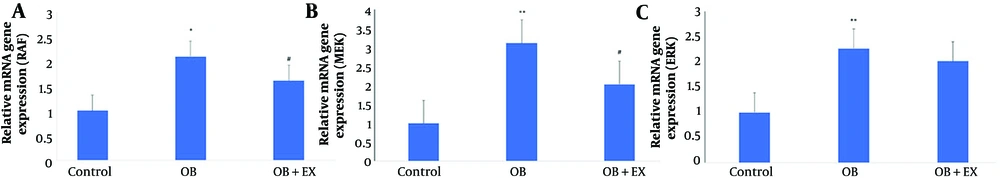

4.3. Exercise Improved Cardiac Hypertrophy Central Genes in Obese Rats

As shown in Figure 3, obesity significantly increased the expression of RAF and MEK genes compared to controls. Eight weeks of EX significantly reduced RAF (Figure 3A) and MEK (Figure 3B) gene expression in cardiac tissue compared to the OB group. Obesity also significantly increased ERK gene expression compared to controls (Figure 3C); however, ERK gene expression did not significantly differ between the OB and OB+EX groups.

Comparison of rapidly accelerated fibrosarcoma (RAF) (A), mitogen-activated protein kinase (MEK) (B), and extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK) (C) gene expression levels among the control, obese (OB), and obese with aerobic exercise (OB+EX) groups (data are presented as mean ± SEM; group comparisons were performed using one-way ANOVA and HSD; * P < 0.05 and ** P < 0.001 vs. control; # P < 0.05 vs. OB group).

5. Discussion

Our findings demonstrate that obesity leads to cardiac hypertrophy, as indicated by increased cardiac hypertrophy indices and altered biomarker levels. Changes in the RAF/MEK/ERK signaling pathway were closely associated with these outcomes, underscoring its central role in cardiac hypertrophy. Notably, eight weeks of treadmill EX mitigated cardiac hypertrophy indicators by modulating the RAF/MEK/ERK pathway.

Excessive carbohydrate intake, especially fructose and sugary beverages, contributes to increased obesity, LDL cholesterol, and triglyceride levels (15). In a rat study, fructose-fed animals gained more weight than those fed sucrose after eight weeks (16). High fructose diets promote fat accumulation and elevate blood triglycerides. Namekawa et al. reported that both high-fat and fructose-rich diets induce hyperlipidemia in rodents (17). Thus, high-fat/high-fructose diets are widely used for inducing obesity in laboratory animals (18).

Obesity or overweight status elevates the risk of cardiovascular diseases (19). Increased left ventricular thickness, or cardiac hypertrophy, is a well-established marker of cardiac pathology resulting from excessive cardiac workload (17). Cardiac hypertrophy involves enlarged myocytes due to overload. Addressing obesity is crucial for preventing early-onset cardiovascular disease; research shows a strong relationship between elevated Body Mass Index and cardiac hypertrophy as well as hypertension (20-22).

Previous research has shown that VEGF-B and SIRT3 are key regulators in the metabolism underlying cardiac hypertrophy; thus, targeting them may provide cardioprotection in heart failure (23). In the present study, eight weeks of aerobic EX effectively reduced the risk of cardiac hypertrophy and improved VEGF-B and SIRT3 levels.

The current results also revealed significantly increased expression of RAF, MEK, and ERK genes in the cardiac tissue of OB rats relative to controls. Yu et al. demonstrated that modulating RAF expression improved hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, as evidenced by normalized end-diastolic lumen dimensions, cardiomyocyte morphology, and heart wall thickness (24). Additionally, studies in children with Noonan syndrome and hypertrophic cardiomyopathy showed that off-label treatment with the oral MEK inhibitor trametinib resulted in improved cardiac function, reduced heart failure biomarkers, and favorable echocardiographic changes (25).

The MAPK pathway, consisting of RAF, MEK, and ERK, is a major cascade activated by receptor tyrosine kinases (RTKs) upon ligand binding. Therapeutic modulation of this pathway presents an opportunity to treat cardiac hypertrophy (26). Our findings are consistent with those of Mathieu et al. (27), who observed an association between obesity and structural and functional cardiac alterations, as well as increased cardiovascular risk factors such as hypertension, dyslipidemia, and inflammation. Obesity exacerbates chronic inflammation, causing cellular damage and stress (28), and activates the I kappa B kinase (IKK), nuclear factor kappa B (NF-kB), and MAPK pathways (27). The MAPK family includes at least four pathways: The ERK1/2, ERK5, p38-MAPK, and c-Jun N-terminal kinases (JNK1/2/3) (29). The MAPK/ERK pathway is implicated in numerous deleterious cellular processes (30), and is activated via a phosphorylation cascade involving three protein kinases: The MAPK kinase, MEK, and MAPK. The MAPK/RAF-MEK-ERK complex is a developmental module involved in inflammatory and oxidative stress processes (31). Matoba et al. demonstrated that elevated plasma free fatty acids increased cell proliferation and p70S6K phosphorylation by activating the MEK/ERK pathway in OB subjects (32). Wang et al. reported that high-fat diets abnormally activate the MAPK pathway in adipocytes. Our results are in agreement, showing that an eight-week high-fat/high-fructose diet increases expression of MAPK downstream genes associated with cardiac hypertrophy indices and biomarkers (33).

We observed significant suppression of RAF and MEK gene expression in OB rats subjected to EX, while ERK gene expression remained unchanged. This suggests that EX may primarily regulate the RAF/MEK/ERK pathway via transcriptional modulation of RAF and MEK. The ERK activity is often modulated post-translationally by phosphorylation rather than transcriptional changes, so unchanged ERK mRNA levels do not necessarily indicate unaltered pathway activity. Compensatory feedback mechanisms or selective targeting of upstream kinases by EX may maintain ERK transcript levels. These findings highlight the complex regulation of the MAPK pathway and the need for further research into ERK phosphorylation status to fully elucidate EX’s effects in obesity. Additionally, gene subfamilies (ERK1: MAPK3 and ERK2: MAPK1) may play roles, as full ERK activation requires phosphorylation at threonine 202 and tyrosine 204 (ERK1) or threonine 185 and tyrosine 187 (ERK2) (31). Longer EX durations might influence ERK expression, warranting further study of isoform-specific roles in EX-induced MAPK modulation.

AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK), a cellular energy sensor activated by EX, has been shown to inhibit the RAF/MEK/ERK pathway and reduce cardiac hypertrophy. This may partly explain the observed effects of aerobic EX. Pharmacological agents such as hydroxyurea, used in conditions like sickle cell disease, can also modulate MAPK signaling indirectly by altering nitric oxide and oxidative stress, highlighting the complexity of cardiac remodeling regulation (34).

Aerobic EX significantly suppressed the RAF-MEK-ERK complex and decreased VEGF-B and SIRT3 concentrations, both biomarkers of cardiac hypertrophy. Further molecular research is needed to clarify the precise mechanisms by which aerobic EX prevents cardiac hypertrophy. Nonetheless, our results suggest that aerobic EX is a promising therapy for obesity-related cardiac disorders.

While our study demonstrates that aerobic EX impacts the RAF/MEK/ERK pathway in obesity-related cardiac hypertrophy, other signaling pathways, such as AMPK and phosphoinositide 3-kinase/protein kinase B (PI3K/AKT), may also be involved. AMPK, an energy sensor activated by EX, exerts antihypertrophic effects by reducing protein synthesis and controlling oxidative stress, and can inhibit MAPK signaling. Thus, reductions in cardiac hypertrophy may be indirectly mediated by AMPK activation. The PI3K/AKT pathway also plays a complex role in cardiac hypertrophy, with both physiological and pathological remodeling depending on upstream signals and activation duration. Interactions between the PI3K/AKT and MAPK pathways may contribute to hypertrophic signaling (35). Therefore, the effect of aerobic EX on RAF and MEK expression may be partially mediated by these additional pathways. Future research should include protein-level analyses and pathway inhibition studies to further clarify these interactions.

The aerobic EX regimen — moderate-speed treadmill running for eight weeks — represents a moderate-intensity EX analogous to 3 - 6 metabolic equivalents (METs) in humans. According to established scaling models (35, 36), this treadmill intensity in rodents is equivalent to brisk walking or light jogging in humans. This aligns with World Health Organization and American Heart Association recommendations for at least 150 minutes of moderate-intensity aerobic EX weekly to promote cardiovascular health. Thus, our results support the use of clinically relevant doses of aerobic EX to mitigate obesity-associated cardiac hypertrophy.

5.1. Conclusions

In summary, our findings indicate that aerobic EX can regulate cardiac hypertrophy in obesity by attenuating or modulating activation of the RAF/MEK/ERK pathway. This effect was clearly demonstrated in a high-fat/high-sugar diet model of obesity in male rats, suggesting a central role for this pathway in EX-induced cardiac hypertrophy responses. While our results are consistent with the literature, further studies are necessary to precisely define the underlying mechanisms and to clarify interactions between the RAF/MEK/ERK pathway and other cardiovascular signaling molecules and physiological parameters. Considering the study’s design, appropriate control groups, and use of an animal model, our results show that a high-fat/high-sugar diet and obesity can modify cardiovascular responses to aerobic EX. These findings have clinical implications for developing personalized EX programs for individuals with overweight or obesity to improve cardiac health, though clinical trials and longitudinal studies in humans are required to confirm applicability. Future studies should explore sex differences, combined dietary effects, and age-related responses to aerobic EX for optimal clinical intervention strategies.

5.2. Limitations

This study has several important limitations. First, the exclusive use of a male rat model limits generalizability to females; sex differences in cardiovascular and metabolic responses to obesity and EX may differentially affect the RAF/MEK/ERK signaling pathway. Second, translational relevance is constrained by species differences and controlled laboratory conditions (diet, housing, and activity) that do not replicate human lifestyle diversity. Third, reliance on a high-fat/high-sugar diet to induce obesity may not represent other obesity etiologies in humans, potentially limiting generalizability to non-diet-induced obesity. Fourth, while the mechanistic links to the RAF/MEK/ERK pathway are supported by the data, causality requires more targeted interventions (e.g., pathway-specific inhibitors or activators) to exclude off-target effects and confirm directionality. Fifth, study duration and EX protocol may influence results; longer-term or varied-intensity regimens might yield different cardiac remodeling insights. Sixth, potential confounders such as baseline metabolic status, physical activity, and circadian influences were not exhaustively controlled. Finally, while our findings align with existing research, replication in independent cohorts and alternative models is needed to strengthen the conclusions’ robustness and generalizability.

![Comparison of Cardiac Hypertrophy indices: Heart/body weight (A) and left ventricle/body weight (B) among the control, obese (OB, high-fat/fructose diet), and obese with aerobic exercise [OB+EX, high-fat/fructose diet plus exercise (EX)] groups (data are presented as mean ± SEM; group comparisons were performed using one-way ANOVA and HSD; * P < 0.05 and ** P < 0.01 vs. control; # P < 0.05 vs. OB group). Comparison of Cardiac Hypertrophy indices: Heart/body weight (A) and left ventricle/body weight (B) among the control, obese (OB, high-fat/fructose diet), and obese with aerobic exercise [OB+EX, high-fat/fructose diet plus exercise (EX)] groups (data are presented as mean ± SEM; group comparisons were performed using one-way ANOVA and HSD; * P < 0.05 and ** P < 0.01 vs. control; # P < 0.05 vs. OB group).](https://services.brieflands.com/cdn/serve/31710/719ef96e7b4832f267b9c5ec8412aa02b3eddde5/jjcmb-17-1-164376-i001-preview.webp)