1. Background

Multiple sclerosis (MS) is a chronic, neurodegenerative, and inflammatory disorder of the central nervous system (CNS) marked by immune-related injury to the myelin sheaths that encase axons, leading to the formation of lesions known as plaques that hinder signal transmission vital for normal neurological function (1). Demyelinating conditions like MS are marked by damage to myelin, the protective layer encasing axons, which facilitates the effective transmission of nerve signals (2). Oxidative stress and persistent inflammation are key factors in the neurodegenerative processes of MS, causing additional harm to sensitive neuronal groups that are already compromised due to lack of metabolic support after demyelination (3). Axons that lack myelin forfeit the metabolic assistance previously given by oligodendrocytes, jeopardizing neuronal wellbeing due to oxidative stress and mitochondrial dysfunction (4). Reactive oxygen species (ROS) leading to oxidative stress, along with other ROS like malondialdehyde (MDA) and hydroxyl radical (HO•), have been identified. Increased lipid peroxidation products also lowered antioxidants such as glutathione peroxidase (GPx) and glutathione disulfide (GSSG) are frequently documented in these scenarios (4, 5). Recent research has concentrated on increased immunological markers in MS as the primary element in MS pathology to enhance patient care and assess clinical trials (1, 6). Moreover, the equilibrium between pro- and anti-inflammatory responses like Interleukin-1 and 4 (IL-1 & IL-4) is essential for the prognosis of patients with sepsis, since a significant anti-inflammatory response can make patients susceptible to secondary infections (7). Additionally, exposure to mixtures of environmental chemicals has been demonstrated to enhance lymphocyte (Lym) levels throughout the immune-inflammatory spectrum, likely via the activation of the IL-6 amplifier due to concurrent exposure to these chemicals (8). In addition, demyelination disrupts neurological functions, leading to issues such as cognitive impairments, particularly in memory, attention, processing speed, and executive functions (9). As a result, learning and memory difficulties, along with cognitive impairments, are frequently observed symptoms in patients with MS (10). This might also be connected to the decrease in neurotrophins in the brain, such as brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) and nerve growth factor-1 (NGF-1), which are crucial for encouraging the proliferation of neural stem cells (NSC) and their differentiation, especially into the oligodendroglial lineage (11). Recent studies have emphasized the therapeutic benefits of water-based exercise and antioxidant supplements in mitigating issues associated with demyelination, including motor coordination, strength, oxidative levels, and myelin synthesis in MS (12, 13). Coenzyme Q10 (CoQ10), also known as Ubiquinone, is an endogenous lipid. It is mainly synthesized intracellularly, while small amounts are obtained from foods such as fish, whole grains, and organ meats (14). Coenzyme Q10, as a lipid-soluble antioxidant within the mitochondrial respiratory chain, demonstrates the capability to enhance remyelination processes in cuprizone models and potentially similar effects in MS patients (15). The study by Khalilian et al. demonstrated that CoQ10 plays a role for the first time in preventing and treating demyelination through reducing oxidative stress and inflammation in the corpus callosum in chronic MS models (15). Randomized controlled trials have shown that CoQ10 supplementation at a dose of 500 mg is capable of reducing inflammatory markers including TNF-α, IL-6, and MMP-9 in MS patients (16, 17). Although direct studies on memory improvement in MS are limited, randomized double-blind clinical trial research has demonstrated that CoQ10 supplementation at a dose of 500 mg daily can improve fatigue and depression in MS patients (18, 19). Additionally, CoQ10 at a dose of 500 mg daily is capable of reducing oxidative stress and increasing antioxidant enzyme activity in relapsing-remitting MS patients (20). Other studies have confirmed that CoQ10 supplementation improves scavenging activity, reduces oxidative damage, and creates a shift toward an anti-inflammatory environment in the peripheral blood of relapsing-remitting MS patients (13). Although these interventions individually demonstrate potential, limited research has assessed their effects when combined. Water-based exercises might influence myelin repair in individuals with MS. Proposed that moderate continuous physical activity might help boost myelin sheath repair and increase the levels of proteins associated with myelination (21). Jin et al. demonstrated that water-based exercise improves short-term memory deficits caused by MS by reducing apoptosis and enhancing the count of caspase-3-positive cells in the hippocampus of rats (22). Aquatic exercise programs have demonstrated the ability to enhance the inflammatory profile of individuals, resulting in reduced levels of pro-inflammatory markers and an overall better inflammatory profile (23). Although the direct impact of aquatic exercise on oxidative stress in MS patients is not fully understood, studies in similar conditions, like Parkinson's disease, have indicated that aquatic exercise can influence oxidative factors by reducing lipid oxidative damage and increasing the function of antioxidant enzymes such as GPx, superoxide dismutase activity (SOD), and catalase (CAT) (24). In the meantime, supplementary exogenous CoQ10 in EAE rats stabilizes mitochondrial function and membrane potential, enhances endogenous antioxidant systems for neuroprotection, alleviates symptoms, and diminishes CNS inflammation, even stopping disease progression in certain groups (13, 19).

2. Objectives

Therefore, using the dependable EAE rat model that replicates key immune and neuropathological features of MS (6), this research intends to evaluate the effects of water-based aerobic exercise combined with CoQ10 supplementation, focusing on memory deficits, oxidative stress, neuroinflammation, and remyelination processes often impaired in MS.

3. Methods

3.1. Animals and Grouping

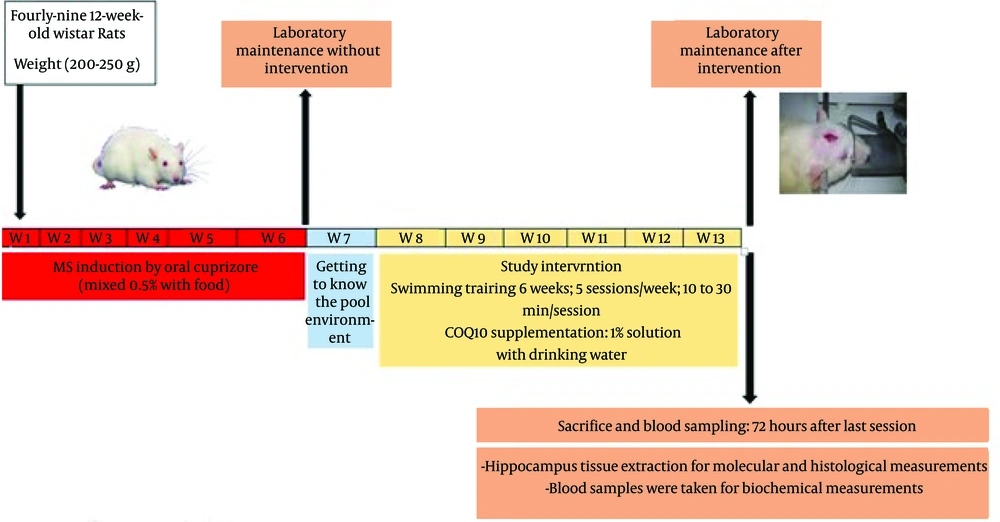

This study was approved by the Ethical Committee of Shahid Chamran University of Ahvaz, Iran (registration code: IR.SCU.REC.1402.042) under the NIH Guidelines for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals (NIH publication, 1996). Forty-nine 12-week-old male Wistar rats with a body weight of 250 ± 50 g were randomly assigned into 7 groups (n = 7): C: Healthy control group; EX: Healthy exercise group; COQ10: Healthy CoQ10 Supplement group; MS: Multiple sclerosis group. Then, the patient groups were induced with MS by using Cuprizone for 6 weeks. After that, the 6-week interventions including aerobic training and COQ10 supplementation were applied. Animals were divided into groups of four rats in transparent polycarbonate cages. Animals were kept four-per-cage with a 12 h light/12 h dark cycle, at a temperature of 25°C, with free access to water and food for seven days for adaptation to the new environment. (Figure 1).

3.2. Multiple Sclerosis Induction

To induce the MS model, animals received a diet containing 0.2% (w/w) CPZ (bis-cyclohexanone oxaldihydrazone, Sigma-Aldrich). CPZ was incorporated into a standard ground rodent diet. Prior to CPZ administration, all rats involved in the study were acclimated to powdered standard chow for 1 week. The CPZ diet was sustained for a duration of 6 weeks until full demyelination occurred (25).

3.3. Coenzyme Q10 Supplementation

Coenzyme Q10 powder was obtained from Sigma Chemical Com Company, USA. Coenzyme Q10 was given daily mixed with drinking water (1% COQ10) throughout 6 weeks of training (26). According to previous studies (14, 26), CoQ10 powder was obtained from sigma chemical com company, USA. COQ10 was administered daily with a dosage of 150 mg/kg/day of CoQ10 mixed in chow during 6 weeks of training.

3.4. Aquatic Exercise Protocol

The rodent pool was used for the aquatic training program. In the swimming exercise group, animals swam daily for 30 minutes, five days a week over a period of 6 weeks. To help the animals in the swimming training group adapt, the training duration was raised from 10 minutes on day one to 30 minutes by the sixth week (Figure 1) (27).

3.5. Spatial Memory Test Using Morris Water Maze

The Morris water maze (MWM) was utilized to examine the spatial memory of the animals. Morris water maze is a circular tank made of Plexiglas featuring a black wall, measuring 140 cm in diameter and 60 cm in height, filled with water to a level of 32 cm. The ideal water temperature is 25 ± 2 degrees Celsius. A dark metallic platform with a diameter of 10 cm is positioned at a distance of 1 to 5 cm under the water surface in the center of the southwest quadrant. During every trial, the rat had 60 seconds to locate the platform's position. After each attempt, the rat was allowed a 30-second break to investigate its surroundings. The rat was removed from the water for approximately 10 minutes and rested in the cage between two blocks. Then animals underwent training four times daily for four days, with the fifth day designated as the probe day, and it was conducted without the platform. Our protocol measured the distance traveled by animals and the time they spent in the target quarter (3).

3.6. Nerve Growth Factor-1, Interleukins Assay and Stress Oxidative Markers Assay

Concentrations of NGF1, IL-1, and IL-4 were determined using ELISA Kits for rats supplied by Sigma Aldrich Co. USA.

3.7. Evaluation of Oxidative Stress Index (OSI) in Hippocampal Tissue Using the Ferric Reducing Ability of Plasma (FRAP) Biochemical Assay

To assess the levels of MDA, GPX, GSH, and GSSG, standard kits were utilized in accordance with the manufacturer's guidelines (RANDOX RANSOD, United Kingdom).

3.8. Immunofluorescence Staining and Morphometric Analysis of Isolated Hippocampus

The brain was carefully removed from the skull for histopathological evaluation of the hippocampus. The brains were dissected and were then processed for histological studies as follows. Then, using a light microscope and with x40 magnification, parameters such as cytoplasm staining and necrosis were prepared in 5 fields of each slide, which contains 5 slices from the area CA1 of the hippocampus were isolated and stained with H&E (hematoxylin and eosin). The physical dissector technique was employed for the quantitative assessment of neuronal populations. We quantified the number of neurons within a counting frame of 10,000 µm², subsequently deriving the mean neuronal density (NA) in distinct subdivisions of the hippocampus utilizing the following formula: NA = ∑Q/∑P×AH, where NA represents cell density, ΣQ denotes the cumulative count of particles identified within the sections, ΣP signifies the number of samples collected within a single observation, A indicates the area of the sampling frame, and H represents the inter-slice distance, or the thickness of each individual slice (28).

3.9. Evaluation of Protein Expression Using Western Blot Method (Klotho & NeuN Assay)

To prepare 20 mL of lysing buffer, Tris base 50 mM (0.3 g), sodium chloride 150 mM (0.43 g), Triton X100 0.1% (0.02 mL), sodium deoxycholate 0.25 percent (0.05 g), SDS 0.1 percent (0.02 g) and EDTA (5.84 g), 1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride (0.009 g) in 20 mL of distilled water. The mixture and its pH was adjusted to 7.4. After adding the mentioned ingredients, the final volume was brought to 50 mL using distilled water. For every 10 mL of solution, 100 μL of protease inhibitor mixture (Sigma, America) was used. Then, 0, 2, 4, 6, 10, 15, and 20 microliters of BSA standard and 20 microliters of tissue homogenous sample were added to the wells of the 96-well plate. 40 microliters of Bradford's reagent was added to each well and pipetting was done. Then 200 microliters of distilled water was added to each well and kept at room temperature for 5 minutes. The optical density of the specimens was measured at a wavelength of 595 nm employing a BioTek ELX800 (USA) microplate reader. The concentration of samples was calculated based on drawing the standard curve of absorbance changes against the concentration of standard samples. By multiplying the number obtained from the number of the standard curve by 50, the amount of protein in tissue homogenous samples was obtained in terms of ug/mL (28).

3.10. Statistical Analyses

The data were expressed as mean ± standard deviation (SD). The Shapiro-Wilk normality test was employed to assess the normal distribution of the data. The Levene's test was utilized to evaluate the homogeneity of variances. A one-way ANOVA, followed by Tukey's post hoc test, was conducted to analyze the data. All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS software version 21 for Windows (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA), with a significance level set at P < 0.05.

4. Results

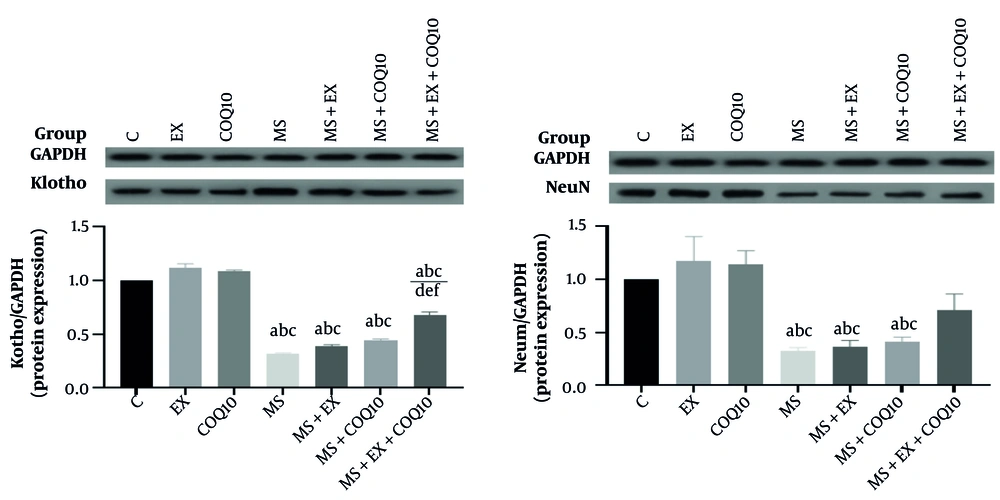

The mean and SD of the animals' weight was 224 ± 18 g. Protein expression results showed a significant difference between groups in Klotho (P ≤ 0.001) and NeuN (P = 0.001). Post-hoc comparisons for Klotho protein showed a significant decrease in MS, MS+EX, MS+COQ10, and MS+EX+COQ10 groups compared to C, EX, and COQ10 groups (P ≤ 0.05). Additionally, there was a significant increase in the MS+EX+COQ10 group compared to MS, MS+EX, and MS+COQ10 groups (P ≤ 0.05). Post-hoc comparisons for NeuN protein showed a significant decrease in MS, MS+EX, and MS+COQ10 groups compared to C, EX, and COQ10 groups (P ≤ 0.05) (Figure 2).

Protein expression in study groups. C: Healthy control group; EX: Healthy exercise group; COQ10: Healthy coenzyme Q10 Supplement group; MS: Multiple sclerosis group. a, a significant decrease compared to the C group; b, a significant decrease compared to the EX-group; c, a significant decrease compared to the COQ10 group; d, a significant increase compared to the MS group; e, a significant increase compared to the MS+EX group; f, a significant increase compared to the MS+COQ10 group.

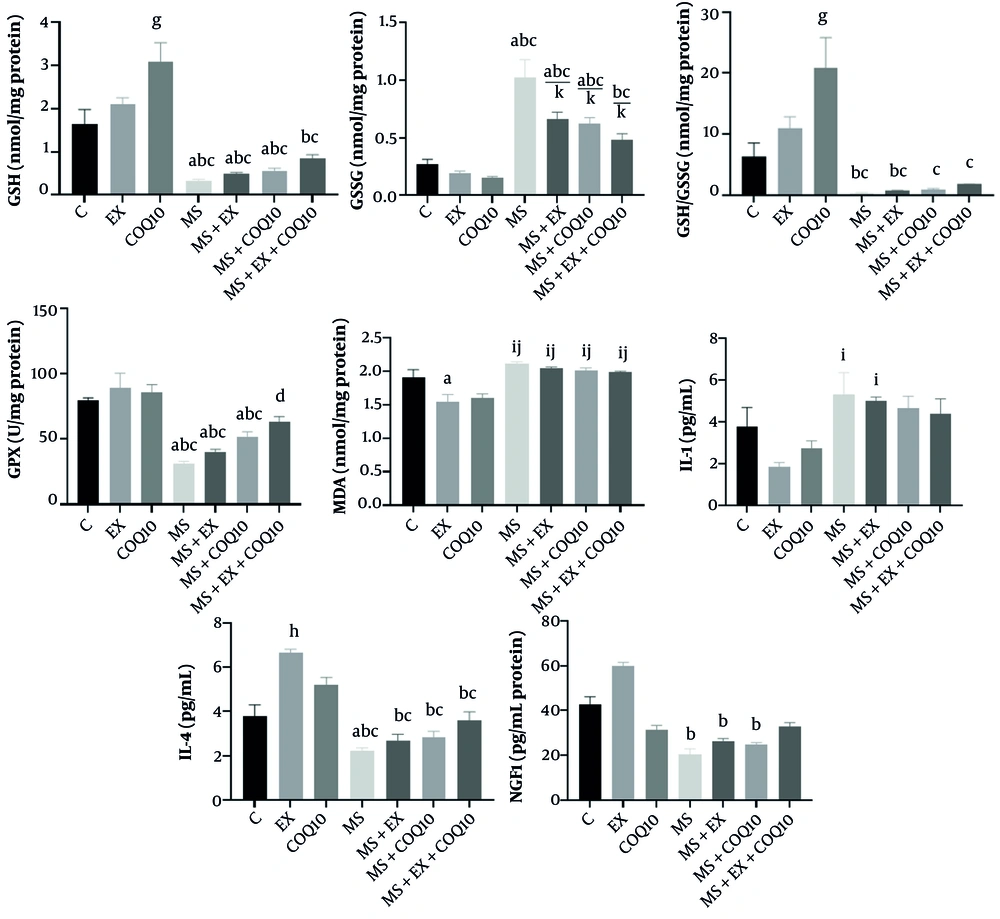

Oxidant/antioxidant analyses revealed considerable intergroup variations in GSH, GSSG, GSH/GSSG ratio, GPX, and MDA (all, P ≤ 0.001). Subsequent post-hoc assessments for GSH indicated a notable enhancement in the COQ10 cohort relative to the control group (P ≤ 0.05). Furthermore, a statistically significant reduction was noted in the MS, MS+EX, and MS+COQ10 groups in comparison to the C, EX, and COQ10 groups (P ≤ 0.05). Additionally, a significant decline was detected in the MS+EX+COQ10 group when compared to the EX and COQ10 groups (P ≤ 0.05).

Post-hoc evaluations for GSSG demonstrated a significant increase in the MS, MS+EX, and MS+COQ10 groups relative to the C, EX, and COQ10 groups (P ≤ 0.05). A significant rise was also observed in the MS+EX+COQ10 group compared to the EX and COQ10 groups (P ≤ 0.05). Moreover, a significant reduction was exhibited in the MS+EX, MS+COQ10, and MS+EX+COQ10 groups when contrasted with the MS group (P ≤ 0.05).

Post-hoc evaluations for the GSH/GSSG ratio revealed a significant increase in the COQ10 group in relation to the C group (P ≤ 0.05). A significant decrease was also noted in the MS and MS+EX groups when compared to the EX and COQ10 groups (P ≤ 0.05). Furthermore, significant reductions were observed in the MS, MS+EX, MS+COQ10, and MS+EX+COQ10 groups in comparison to the COQ10 group (P ≤ 0.05).

Post-hoc evaluations for GPX indicated a significant decline in the MS, MS+EX, and MS+COQ10 groups compared to the C, EX, and COQ10 groups (P ≤ 0.05). A significant increase was also recorded in the MS+EX+COQ10 group relative to the MS group (P ≤ 0.05).

Post-hoc evaluations for MDA demonstrated a significant decrease in the EX group compared to the C group (P ≤ 0.05). Furthermore, a significant increase was observed in the MS, MS+EX, MS+COQ10, and MS+EX+COQ10 groups in comparison to the EX and COQ10 groups (P ≤ 0.05) (Figure 3).

Oxidant/antioxidant factors, IL-1 (interleukin), IL-4, and NGF1 in study groups. C: Healthy control group; EX: Healthy exercise group; COQ10: Healthy coenzyme Q10 Supplement group; MS: Multiple sclerosis group. a, a significant decrease compared to the C group; b, a significant decrease compared to the EX group; c, a significant decrease compared to the COQ10 group; d, a significant increase compared to the MS group; g, a significant increase in the COQ10 compared to the C group; h, a significant increase in the EX compared to the C group; i, a significant increase compared to the EX group; j, a significant increase compared to the COQ10 group; k, a significant decrease compared to the MS group.

In addition, IL-1 exhibited significant intergroup discrepancies (P = 0.009). Post-hoc evaluations revealed a significant increase in the MS and MS+EX groups relative to the EX group (P ≤ 0.05) (Figure 3). Interleukin-4 demonstrated significant intergroup differences (P ≤ 0.001). Subsequent post-hoc analyses indicated a significant increase in the EX group compared to the control group (P ≤ 0.05). Moreover, a significant decrease was noted in the MS group relative to the control group (P ≤ 0.05). Additionally, significant reductions were observed in the MS, MS+EX, MS+COQ10, and MS+EX+COQ10 groups when compared to the EX and COQ10 groups (P ≤ 0.05) (Figure 3).

Nerve growth factor-1 revealed a significant intergroup discrepancy (P = 0.011). Post-hoc evaluations demonstrated a significant decrease in the MS, MS+EX, and MS+COQ10 groups in comparison to the EX group (P ≤ 0.05) (Figure 3).

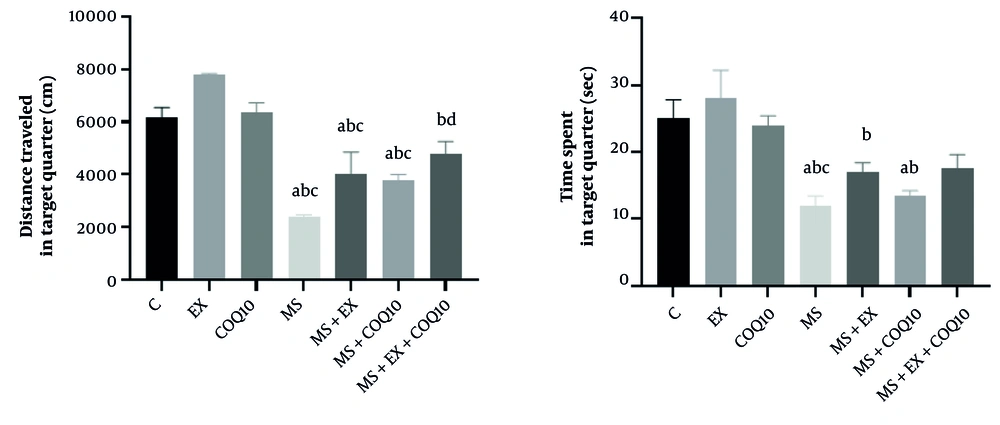

The results of the MWM to assess spatial memory were evaluated, and the results showed that both distances traveled (P ≤ 0.001) and time spent (P = 0.001) in target quarter domains showed significant between-group differences. Post-hoc comparisons for distance traveled showed a significant decrease in MS, MS+EX, and MS+COQ10 groups compared to C, EX, and COQ10 groups (P ≤ 0.05). Also, a significant decrease was observed in the MS+EX+COQ10 group compared to the EX group (P ≤ 0.05). On the other hand, a significant increase was shown in the MS+EX+COQ10 group compared to the MS group (P ≤ 0.05). Post-hoc comparisons for time spent showed a significant decrease in MS and MS+COQ10 groups compared to the C group (P ≤ 0.05). Also, a significant decrease was observed in the MS, MS+EX, and MS+COQ10 groups compared to the EX group (P ≤ 0.05). As well as a significant decrease shown in the MS group compared to the COQ10 group (P ≤ 0.05) (Figure 4).

Distance traveled and time spent in target quarter in Morris water maze (MWM) Test for study groups. C: Healthy control group; EX: Healthy exercise group; COQ10: Healthy coenzyme Q10 supplement group; MS: Multiple sclerosis group. a, significant decrease compared to C; b, significant decrease compared to EX; c, significant decrease compared to COQ10; d, a significant increase compared to the MS group.

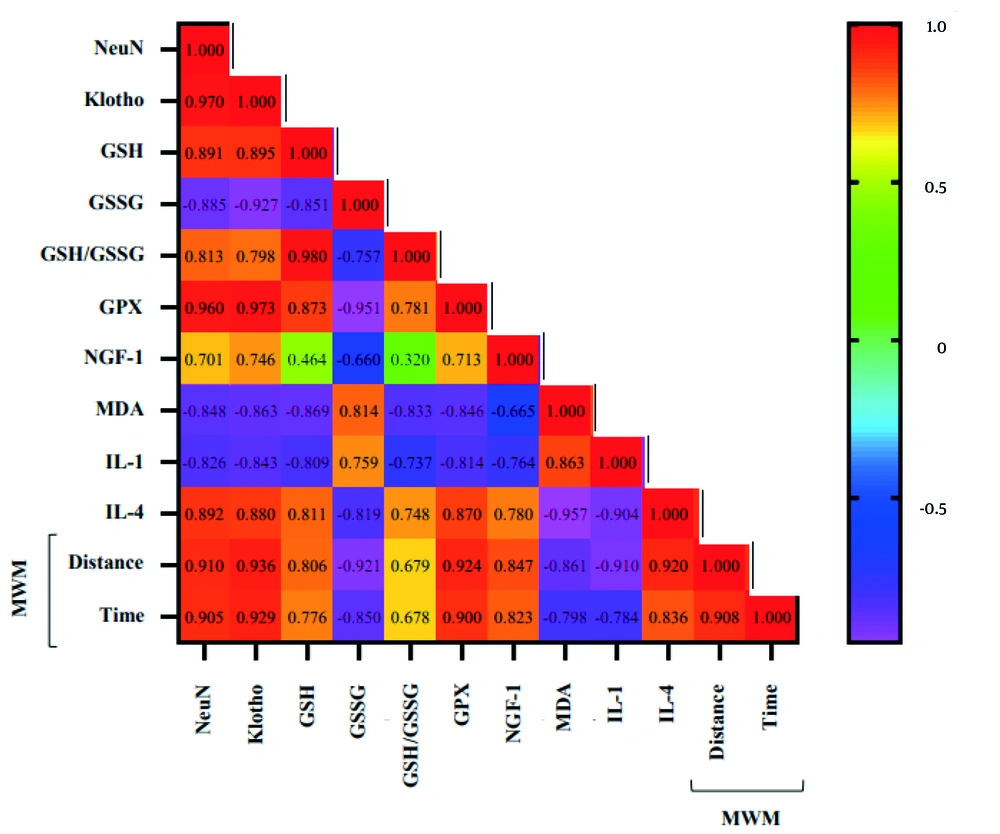

Finally, the result of the Pearson correlation showed a significant direct correlation between NeuN with Klotho, GSH, GSH/GSSG ratio, GPX, NGF-1, IL-4, and distance and time of the MWM test (all, P ≤ 0.05), and a significant inverse correlation with GSSG, MDA, and IL-1 (all, P ≤ 0.05). Also, we found a significant direct correlation between Klotho with GSH, GSH/GSSG ratio, GPX, NGF-1, IL-4, and distance and time of the MWM test (all, P ≤ 0.05), and a significant inverse correlation with GSSG, MDA, and IL-1 (all, P ≤ 0.05). A significant direct correlation was observed between GSH with GSH/GSSG ratio, GPX, IL-4, and distance and time of the MWM test (all, P ≤ 0.05), and a significant inverse correlation with GSSG, MDA, and IL-1 (all, P ≤ 0.05). A significant direct correlation was observed between GSSG with MDA and IL-1 (both, P ≤ 0.05), and a significant inverse correlation with GSH/GSSG ratio, GPX, NGF-1, IL-4, and distance and time of the MWM test (all, P ≤ 0.05). A significant direct correlation was observed between GSH/GSSG ratio with GPX, IL-4, and distance and time of the MWM test (all, P ≤ 0.05), and a significant inverse correlation with MDA and IL-1 (both, P ≤ 0.05). A significant positive correlation was found between GPX with NGF-1, IL-4, and distance and time of the MWM test (all, P ≤ 0.05), and a significant inverse correlation with MDA and IL-1 (both, P ≤ 0.05). A significant direct correlation was observed between NGF-1 with IL-4 and distance and time of the MWM test (all, P ≤ 0.05), and a significant inverse correlation with MDA and IL-1 (both, P ≤ 0.05). A significant direct correlation was observed between MDA with IL-1 (P ≤ 0.001), and a significant inverse correlation with IL-4 and distance and time of the MWM test (all, P ≤ 0.05). A significant inverse correlation was observed between IL-1 with IL-4 and distance and time of the MWM test (all, P ≤ 0.05). A significant direct correlation was observed between IL-4 with distance and time of the MWM test (both, P ≤ 0.05). Finally, a significant direct correlation was observed between distances with time in the MWM test (P ≤ 0.001) (Figure 5).

5. Discussion

The aim of the present study was to investigate the effects of six weeks of aerobic aquatic exercise and COQ10 supplementation on memory impairment and myelin repair in cuprizone-induced MS. The results showed that while cuprizone-induced demyelination led to a significant decrease in the relative protein expression of Klotho in the hippocampus of rats, data analysis showed that compared to the MS group, a significant increase was found in the relative protein expression of Klotho only in the EX+COQ10 group. Although other groups showed some increase in the expression of Klotho, these were not significant. Regarding the NeuN gene, however, we found some increase in the relative protein expression of NeuN, especially in the EX+COQ10 group after interventions, but these changes are not statistically significant. Based on our knowledge, this is the first investigation assessing the effects of the combination of aquatic exercise and COQ10 on the relative protein expression of NeuN and Klotho in an animal model of demyelination. However, some studies have shown the positive effects of combining aerobic exercise with COQ10 supplementation on the myelination of nerve fibers in animal models of demyelination. In a study by Khalilian et al. (15), COQ10 supplementation enhances remyelination and regulates the inflammation effects of cuprizone in patients with MS. Another recent study found that rats exposed to cuprizone and subjected to aerobic exercise and probiotic consumption showed increased levels of myelin basic protein (MBP) compared to the demyelination group (29). Combined exercise training with COQ10 supplementation led to improved muscular function, including walking, in patients with MS (29). However, there is no specific mention of the relative protein expression of Klotho in the animal models of demyelination in the studies provided. A systematic review and meta-analysis suggest that exercise training, including aerobic training, may stimulate Klotho expression, and circulating S-Klotho protein is altered after chronic exercise training, indicating that Klotho may be considered an exercise (30). Additionally, continuous aerobic exercise increased Klotho mRNA and protein expression in the brain and kidneys compared to the control group (31). Therefore, it can be inferred that aquatic aerobic exercise may have a similar effect on Klotho protein expression as other forms of aerobic exercise, but further specific studies on aquatic aerobic exercise are needed to confirm this. It seems that higher levels of oxidative stress and stressful conditions lead to S-Klotho production (30) and exercise can reverse this blunt (31). This may be related to the attenuation in the stress oxidative loads by aerobic exercise (32). Another potential rationale for the exercise-induced fluctuations in Klotho levels could be associated with the exercise's anti-inflammatory properties; as we observed in our results (33). It is recognized that inflammation diminishes the expression of Klotho, resulting in premature aging and age-related complications. Consequently, it is notable to assert that the regulation of inflammation through exercise may have a significant influence on augmenting Klotho levels in individuals (34). While aquatic exercise and COQ10 did not significantly alter NeuN protein expression in this study, they may still mitigate MS risk through other mechanisms. For instance, COQ10 enhances electron transport chain function (35), which could improve neuronal metabolism. Exercise can also stimulate neurotrophic factors like BDNF, synaptogenesis, and cerebral blood flow (36). Further research into these pathways could elucidate the neuroprotective potential of non-pharmacological therapies for MS disease prevention. Some possible factors may explain the lack of a significant effect of our interventions on NeuN expression. The intensity or duration of the aquatic exercise may have been insufficient to drive neuronal proliferation. Prior studies indicate that longer or more vigorous aquatic training can increase NeuN expression and hippocampal neurogenesis in animal models (37). Furthermore, the amount and bioavailability of supplemental COQ10 might not have been sufficient to enhance neuronal survival. Exploration of higher doses, different formulations, or combined antioxidants such as COQ10 and vitamin E may be considered (38). Ultimately, because exercise temporarily raises oxidative stress (39), an extended intervention might be required for antioxidant adjustments to occur. Concerning the oxidative stress levels, our findings indicated that MS induction caused a notable rise in hippocampal MDA levels, while aquatic exercise and COQ10 supplementation resulted in a minor decrease in hippocampal MDA levels; however, this decrease was not statistically significant. Concerning GPX, MS induction resulted in a notable reduction in hippocampal GPX levels, and in comparison to the MS group, only EX + COQ10 resulted in a considerable increase in GPX levels. Other treatments (EX or COQ10) also resulted in a few non-significant increases. For GSH, GSSG, and the GSH/GSSG ratio, we observed a notable decrease in the levels of all variables following MS induction (in comparison to the healthy group). Additionally, concerning the interventions, within the GSH, all three interventions (EX, COQ10, and EX+COQ10) led to a notable increase. In the other two variables, none of the interventions produced a notable change, although a minor increase was observed. Oxidative stress likely has the most significant impact on the development of neurodegenerative diseases (9). Exercise, however, can increase oxygen consumption in muscles and result in exercise-induced oxidative stress, but also, regular exercise such as aquatic training can reduce oxidative stress load in neurodegenerative diseases (40). There is limited research on the effects of aquatic exercises on stress oxidative load in MS cases, but some recent studies have shown the benefits of exercise in water for people with neurodegenerative disorders. Exercising in water provides physical and mental benefits while minimizing stress on the body. A study by Dani et al. (41) showed that aquatic exercises modulate antioxidant enzyme activity via decreasing CAT activity, increasing SOD, and increasing the ratio of CAT/SOD in patients with Parkinson's disease immediately and 30 days after the first session. Aquatic exercise places less mechanical stress on the body than land-based exercise, while providing resistance that can improve strength and cardiorespiratory fitness. This type of exercise stimulates the production of GPx and GSS, which neutralize free radicals and reduce oxidative damage to cells and tissues. Aquatic exercises may also modulate stress oxidative in MS through enhancing oxygenated hemoglobin (O2Hb), as demonstrated by Pollock et al. (42). Our research indicated that COQ10 slightly lowered MDA levels in the hippocampus, which is a marker of lipid peroxidation caused by oxidative stress. An increase in the antioxidant enzymes GPx and GSS was observed following the COQ10 intervention or the combination of aquatic exercise with COQ10, suggesting enhanced antioxidant capacity. Sanoobar et al. examined the impact of CoQ10 supplementation on oxidative stress and antioxidant enzyme activity in individuals with MS and determined that a daily dose of 500 mg of CoQ10 can lower oxidative stress and enhance antioxidant enzyme activity in patients with relapsing-remitting MS, as evidenced by reduced MDA levels, elevated serum TAC, and increased SOD and GPx activity in comparison to the control group (20). Nonetheless, we did not observe any notable changes in the level of MDA following exercise, CoQ10, or their combination. Certain studies have shown that CoQ10 supplementation results in an increase in GSH levels (43-45). GSH and GPx are essential in the defense system against oxidative stress due to their antioxidative characteristics (46). It is well recognized that ROS can deactivate GPx and glutathione reductase (47). Q10 efficiently hinders the formation of ROS and the overproduction of NO, thus stopping the inactivation of GPx and the reduction of GSH (48). Consistent physical exercise, along with vitamins and oligomolecules, leads to reduced IL-6 levels and elevated IL-10, impacting the oxidative metabolism ability (40). Concerning NGF1 and spatial memory, our findings indicated a notable decline in both spatial memory and NGF1 levels following the induction of demyelination in rats. Additionally, the results from the MWM used to evaluate spatial memory indicated a notable decrease in both the distance covered and the time spent in the target area for the MS group when compared to the healthy control groups. Outcomes of the interventions indicated that solely EX+ COQ10 led to the distance covered in the target zone by the animals. No notable changes occurred in other groups or variables following the interventions. NGF1 plays a role in biological functions like protecting neurons, enhancing plasticity, promoting neuron regeneration, and improving memory, with its secretion influenced by consistent aerobic exercise. It has been reported that there is a reduction in neuron death and demyelination following the administration of NGF into the white matter of spinal cord samples (49). Radak et al. state that consistent swimming boosts NGF levels in rats' brains, which correlates positively with enhanced memory in mice while negatively correlating with oxidative stress (39). Activity and training in water can enhance neurogenesis in the subventricular zone by raising NGF and synapsin I levels (50). This study has several limitations. First, the use of the CPZ animal model may not fully reflect the pathophysiology of human MS, as this model focuses more on demyelination rather than autoimmune inflammation. Second, the small sample size (n = 7 per group) may have limited the statistical power of the study. Third, the intervention duration (6 weeks) may not be sufficient to assess long-term effects. Also, the lack of assessment of stress markers may have affected the results. Additionally, measurement techniques such as Western blot and immunofluorescence may be influenced by technical variables such as sample quality or method sensitivity. These limitations should be considered in interpreting results and designing future studies.

5.1. Conclusions

Although MS induction caused a notable decrease in NGF1, GSSG, GPX, IL-1, and IL-4 levels and an increase in MDA levels, aquatic exercise supplemented with COQ10 may enhance memory impairments and oxidative stress by boosting Klotho Protein expression, improving the distance traveled in the MWM, and raising GPX and GSSG levels in a demyelination animal model. Collectively, these results indicate that aquatic exercise and COQ10 may function as antioxidant and neuroprotective treatments for rat models of MS.