1. Background

Doxorubicin (DOX) is an anthracycline antineoplastic agent widely used in the treatment of solid tumors and certain leukemias; however, its clinical application is limited due to the development of acute and chronic cardiotoxicity (1). Experimental and review studies indicate that the molecular mechanisms underlying DOX-induced cardiac toxicity include increased production of reactive oxygen species (ROS), mitochondrial dysfunction, nuclear and mitochondrial DNA damage, and activation of programmed cell death pathways (apoptosis), ultimately leading to functional impairment and heart failure (2). In response to DNA damage, the DNA damage response (DDR) system is activated, with two central kinases — ATM and ATR — mediating the activation of downstream pathways (ATM-CHK2 and ATR-CHK1) depending on the type and stage of damage, thereby facilitating cell cycle arrest, DNA repair, or induction of cell death (3). ATR is particularly critical in responding to replication stress and single-stranded DNA (ssDNA) lesions. Alterations in DDR factor activity and expression can decisively influence cardiomyocyte fate following DOX exposure (4). The tumor suppressor protein p53 functions as a cellular gatekeeper and is activated in response to oxidative stress and DNA damage induced by DOX. By mediating cell cycle arrest, regulating repair mechanisms, and/or inducing apoptosis, p53 plays a pivotal role in determining cardiomyocyte survival (5). Multiple studies have shown that DOX-induced upregulation and activation of p53 are associated with cardiomyocyte apoptosis, mitochondrial dysfunction, and exacerbated cardiotoxicity, suggesting that modulation of p53 expression and activity may represent a key cardioprotective target (2).

Beyond pharmacological interventions, exercise has emerged as a non-pharmacological strategy capable of modulating multiple physiological pathways — including enhancement of antioxidant capacity, improvement of mitochondrial function, attenuation of inflammation, and promotion of cellular repair networks — thereby providing protection against DOX-induced cardiotoxicity (6, 7). Animal and review studies indicate that diverse exercise regimens (voluntary or forced, short- or long-term) can reduce ROS, improve mitochondrial homeostasis, and modulate apoptotic signaling, collectively preserving cardiac function under DOX stress (8, 9). Nevertheless, precise molecular mechanisms, particularly at the level of DDR gene expression (e.g., ATR) and apoptotic signaling factors such as p53, remain incompletely understood.

Regarding exercise modality, swimming and treadmill running elicit distinct physiological profiles: Swimming is a non-weight-bearing activity with buoyancy effects and unique hemodynamic responses (10), whereas treadmill running is a weight-bearing exercise with distinct mechanical and metabolic patterns (11). Comparative studies suggest that swimming, particularly endurance swimming, effectively mitigates DOX-induced oxidative cardiac damage and enhances antioxidant indices (12). Conversely, treadmill training, depending on intensity and duration, also confers protective effects but may differentially influence cardiomyocyte structure and function (13). These biomechanical and metabolic differences may translate into distinct patterns of DDR gene regulation, including ATR, and apoptotic regulators such as p53. Despite supportive evidence, systematic comparisons of how these two exercise modalities affect ATR and p53 expression under DOX exposure are limited.

Studies directly examining exercise-mediated modulation of p53 indicate that physical activity can regulate p53 activity and expression across tissues, including the heart. In some models, exercise attenuates pro-apoptotic p53 features and enhances mitochondrial protection; however, responses are context-dependent, influenced by baseline health status, exercise type/intensity, and timing relative to drug administration (14-17). In contrast, investigations of ATR and the ATR-CHK1 pathway under genotoxic stress, including DOX, reveal a dual role: Promoting DNA repair and cell survival on one hand, while chronic activation may contribute to maladaptive cellular responses on the other (18-20). Therefore, it remains unclear whether exercise “enhances” protective ATR signaling or merely “modulates” it, and how these effects ultimately impact p53 and apoptotic outcomes.

Key knowledge gaps include: (1) A lack of direct, comparative evidence on how two common endurance exercise modalities (swimming and treadmill running) differentially influence critical DDR molecules such as ATR and the genomic guardian p53 in the DOX-stressed heart; (2) uncertainty regarding the dependence of responses on exercise parameters (intensity, duration, timing relative to DOX); and (3) limited integrated data linking molecular alterations (gene/protein expression) with functional and morphological cardiac indices in a unified model.

Doxorubicin remains a cornerstone in cancer chemotherapy; however, its cumulative cardiotoxic effects are a major clinical concern. The cardiotoxicity of DOX is primarily mediated by the overproduction of ROS, mitochondrial DNA damage, and activation of pro-apoptotic signaling cascades. Aerobic exercise has been reported to upregulate antioxidant defenses and maintain mitochondrial integrity, thereby counteracting oxidative and apoptotic pathways induced by DOX. Recent evidence also supports the cardioprotective role of aerobic training in combination with bioactive compounds such as crocin or berberine against methamphetamine-induced cardiac injury (21). Similarly, aerobic exercise with curcumin has been shown to attenuate necroptosis pathways in the liver following cadmium exposure (22). These findings collectively highlight the potential of exercise to modulate cell death and DNA damage mechanisms across tissues.

2. Objectives

Accordingly, the present study aimed to determine whether continuous or interval aerobic exercise could modulate the expression of key DNA damage-response proteins (ATR, p53) in the cardiac tissue of DOX-treated mice. The present study was designed to compare the effects of two aerobic exercise modalities — swimming and treadmill running — on ATR and p53 gene expression in the hearts of healthy mice exposed to DOX. We hypothesize that both exercise types, relative to sedentary controls, will attenuate DOX-induced cardiotoxicity via modulation of antioxidant defenses and DDR pathways; however, the patterns of ATR and p53 expression and the magnitude of protective effects are expected to differ between modalities. For instance, swimming may exert greater influence on antioxidant indices and ATR regulation, whereas treadmill running may differentially affect p53-mediated apoptotic pathways. Findings from this study may provide mechanistic insights into exercise-mediated mitigation of drug-induced cardiotoxicity and inform the optimization of rehabilitation and prophylactic strategies for patients undergoing chemotherapy.

3. Methods

3.1. Animals and Experimental Design

In this experimental study, 48 adult male Wistar rats (8 weeks old, 200 - 220 g) were obtained from the Animal Center of Shahid Chamran University of Ahvaz, Iran. Animals were housed under controlled conditions with a temperature of 25 ± 2°C, relative humidity of 55 ± 15%, and a 12-hour light/dark cycle. Standard rodent chow (Parsfeed, Iran) and water were provided ad libitum. Rats were acclimated to laboratory conditions for two weeks prior to the experiment. Thirty-two adult male mice (8 weeks old) were housed under controlled temperature (22 ± 2°C), 12:12 h light-dark cycles, and ad libitum access to standard chow and water. Mice were randomly divided into four groups (n = 8 each): Control (C), DOX (D), DOX+moderate continuous training (D+MCT), and DOX+interval training (D+IT). Randomization was performed using a computer-generated random sequence. The sample size was estimated using GPower 3.1 software (effect size = 0.8, α = 0.05, power = 0.8) based on prior studies of DOX cardiotoxicity. Animals were randomly assigned to six groups: C (negative control), D (positive control), swimming exercise (S), swimming+DOX (DS), treadmill exercise (T), and treadmill+DOX (TD). Control animals received intraperitoneal (IP) injections of saline, whereas DOX-treated groups received DOX (4 mg/kg, IP) once weekly for five consecutive weeks (23). Injections were administered 24 hours after the last weekly exercise session.

3.2. Swimming Exercise Protocol

Swimming training was conducted in a glass tank (100 × 50 × 70 cm) filled with water to a depth of 40 cm at 35°C. The swimming program included an initial familiarization phase followed by a training phase. During the first week, rats swam for 10 minutes on day 1, with daily increments of 10 minutes until reaching 60 minutes per session. The training phase consisted of 60 minutes per day, 5 days per week, for 6 weeks (24). To eliminate the acute effects of the final exercise session, the swimming program ended 48 hours prior to tissue sampling. The MCT were performed in swimming protocol for 6 weeks, 5 days/week. The MCT program consisted of continuous running at 60 - 70% VO2max intensity bouts.

3.3. Treadmill Exercise Protocol

Rats were acclimated to treadmill running for 5 days (10 minutes/day at 10 m/min, 0° incline). To accommodate nocturnal activity patterns, the front of the treadmill lanes was covered with a dark paper, while a shock grid was placed at the rear. A mild electrical stimulus (30 V, 0.5 A) was applied manually for less than 2 seconds if animals remained on the grid for over 10 seconds. Following acclimation, treadmill training was conducted for 25 - 54 minutes per session at 15 - 20 m/min, 5 days per week, for 6 weeks (25). The MCT were performed on a motorized treadmill for 6 weeks, 5 days/week. The MCT program consisted of continuous running at 60 - 70% VO2max intensity bouts.

3.4. Sample Collection

At the end of the experimental period, rats were anesthetized with ketamine hydrochloride (100 mg/kg) and xylazine (10 mg/kg). Blood samples were collected via cardiac puncture, and hearts were excised and stored at -80°C for further analysis.

3.5. Western Blot Analysis

Protein expression of ATR and p53 was assessed using western blotting. Briefly, heart tissues were homogenized in 250 µL RIPA buffer containing 150 mM NaCl, 0.1% SDS, 25 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.4), 1 mM NaF, 1 mM PMSF, and protease/phosphatase inhibitors (Sigma, USA) using a Heidolph homogenizer (Germany). Homogenates were centrifuged at 10,000 × g for 15 minutes at 4°C. Supernatants were collected, aliquoted, and stored at -70°C until analysis. Protein concentrations were determined using the Bradford assay. Samples (20 µg) were separated on 10% SDS-PAGE gels and transferred to PVDF membranes (Amersham, USA). Membranes were blocked with 5% nonfat milk and incubated overnight at 4°C with primary antibodies against ATR (E1S3S) Rabbit mAb (#13934, Cell Signaling Technology, USA) and p53 (1C12) Mouse mAb (#2524, Cell Signaling Technology, USA). After three washes with TPBS (PBS + 0.1% Tween 20), membranes were incubated with HRP-conjugated secondary antibodies (anti-rabbit IgG, #2790, Cell Signaling Technology, USA) at room temperature for 1 hour and washed again three times with TPBS. Protein signals were visualized using an ECL detection kit (ParsTos, Iran) and imaged with a Fusion X chemiluminescence system (Vilber, USA). Densitometric analysis was performed using Fusion X software and normalized to the control group.

3.6. Molecular Analysis

Cardiac tissues were collected 48 h after the final training session. Expression levels of ATR and p53 were analyzed by quantitative RT-PCR using β-actin as the reference gene. The ΔΔCt method was used for relative quantification.

3.7. Statistical Analysis

Data were analyzed using one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s post-hoc test (GraphPad Prism 9). Data are expressed as mean ± SEM. Normality was confirmed using the Shapiro-Wilk test, and statistical significance was set at P < 0.05.

4. Results

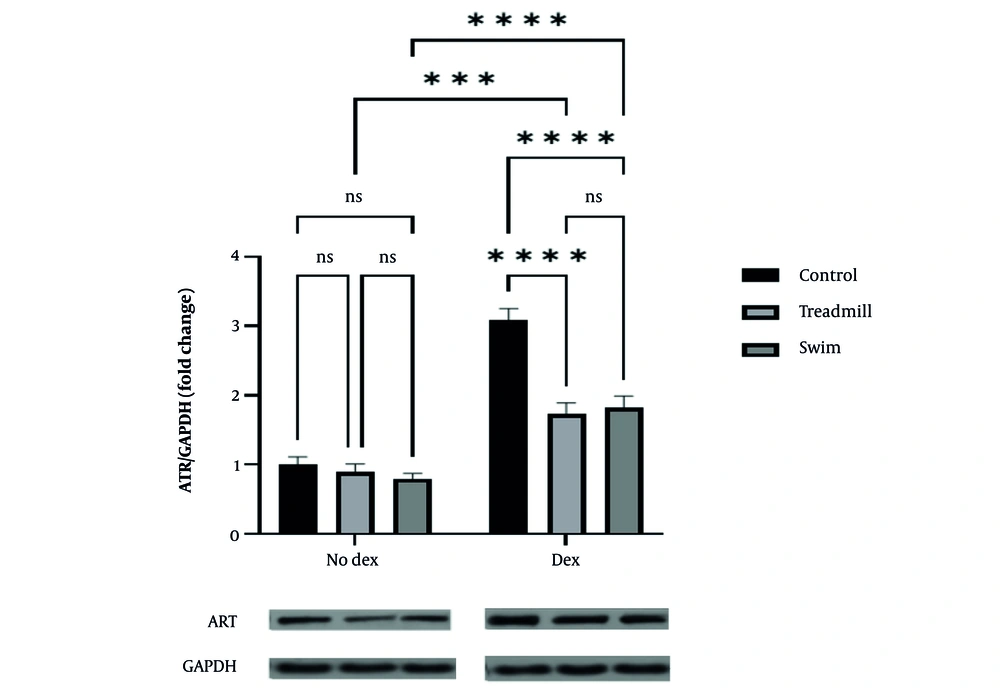

Analysis of ATR and p53 gene expression in rat cardiac tissue revealed that DOX administration significantly upregulated both genes in the control group. For ATR, under no-doxorubicin conditions (No Dex), there were no significant differences among the control, treadmill, and swimming groups. However, in the doxorubicin-treated groups (Dex), ATR expression was markedly elevated in the control group (P < 0.0001). Both aerobic exercise modalities, treadmill and swimming, significantly attenuated ATR expression compared to the control+DOX group (treadmill: P < 0.001; swimming: P < 0.0001), with no significant difference between the two exercise types (Figure 1).

Effect of two aerobic exercise modalities (swimming and treadmill) on ATR gene expression in cardiac tissue of healthy mice treated with doxorubicin (DOX). Fold change of ATR expression relative to GAPDH is shown for control, treadmill, and swimming groups under no-doxorubicin (No Dex) and Dex conditions. Doxorubicin administration significantly increased ATR expression in the control group (**** P < 0.0001). Both aerobic exercise interventions significantly attenuated ATR expression compared to the control+DOX group (treadmill: *** P < 0.001; swimming: **** P < 0.0001), with no significant (ns) difference observed between the two exercise types. Representative western blot images of ATR and GAPDH proteins are shown below the graph. Data are presented as mean ± SEM.

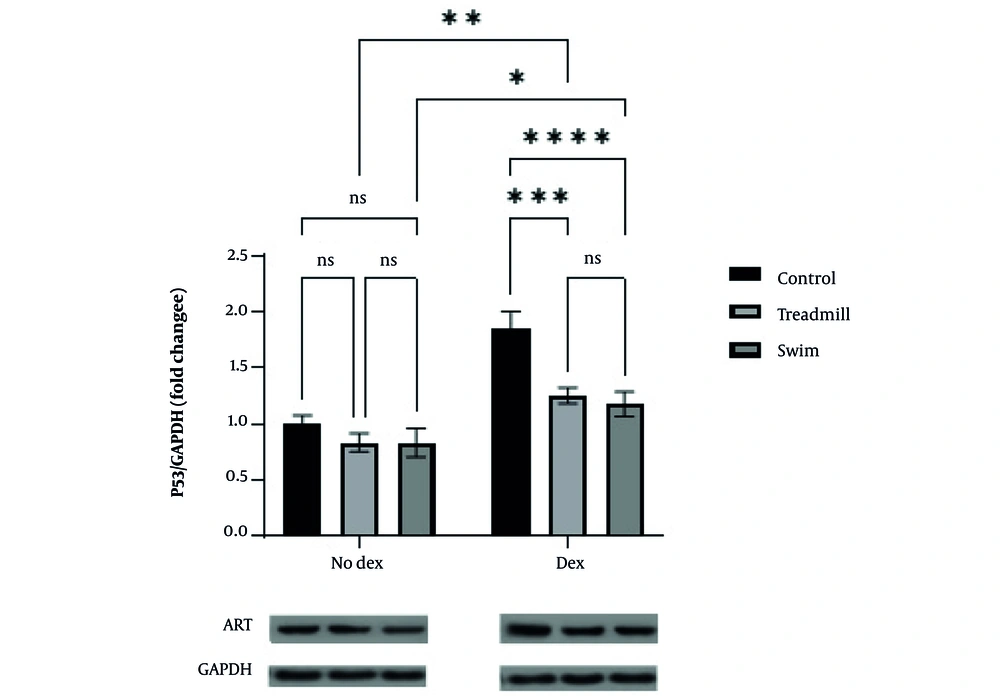

A similar pattern was observed for p53. In the No Dex condition, p53 expression did not differ significantly among control, treadmill, and swimming groups. Doxorubicin administration significantly increased p53 expression in the control group (P < 0.05, P < 0.01, P < 0.001, P < 0.0001). Both treadmill and swimming exercise significantly reduced p53 expression relative to the control+DOX group (treadmill: P = 0.0002; swimming: P < 0.0001), with no significant difference observed between exercise modalities (Figure 2).

Effect of two aerobic exercise modalities (swimming and treadmill) on p53 gene expression in cardiac tissue of healthy mice treated with doxorubicin (DOX). Fold change of p53 expression relative to GAPDH is shown for control, treadmill, and swimming groups under no-doxorubicin (No Dex) and Dex conditions. Doxorubicin administration significantly increased p53 expression in the control group (* P < 0.05, ** P < 0.01, *** P < 0.001, **** P < 0.0001). Both aerobic exercise interventions significantly attenuated p53 expression compared to the control+DOX group, with no significant (ns) difference between the two exercise modalities. Representative western blot images of p53 and GAPDH proteins are shown below the graph. Data are presented as mean ± SEM.

Doxorubicin administration significantly increased cardiac ATR and p53 expression compared with controls (P < 0.001). Both exercise regimens attenuated these effects, with interval training showing greater downregulation (P < 0.05). Fold changes in ATR and p53 expression were clearly reported for all groups, demonstrating a marked reduction in DNA damage signaling after exercise training. Overall, these findings indicate that DOX induces upregulation of ATR and p53 in cardiac tissue, whereas aerobic exercise (swimming and treadmill) effectively mitigates this increase. These results highlight the protective role of aerobic training against DOX-induced deleterious effects on the heart.

5. Discussion

The present study demonstrated that DOX administration significantly upregulated ATR and p53 protein expression in cardiac tissue, consistent with the well-established role of DOX in activating DDR and apoptotic pathways. Both aerobic exercise modalities, swimming and treadmill, effectively attenuated this upregulation, with no significant differences observed between the two exercise types. These findings suggest that the cardioprotective effects of aerobic exercise against DOX-induced toxicity are more dependent on the general physiological benefits of exercise — such as reducing oxidative stress, improving mitochondrial homeostasis, and modulating cell death pathways — than on the specific type of activity.

Previous studies have also reported the protective effects of aerobic training against DOX-induced cardiotoxicity. For instance, swimming exercise in animal models reduced oxidative damage and cardiac fibrosis while activating NRF2-dependent antioxidant pathways (26). Similarly, treadmill training preserved cardiac function and reduced cardiac accumulation of DOX in mice (27). These results align with our findings, indicating that both aerobic exercise modalities, despite biomechanical differences, can exert similar cardioprotective effects.

A key observation of this study was the reduction of p53 expression following exercise. The DOX-induced p53 upregulation in the heart has been directly linked to apoptosis and mitochondrial dysfunction (28). Recent evidence suggests that modulation of the p53 pathway can mitigate cardiotoxicity by reducing oxidative stress and apoptosis (29). Our results indicate that aerobic exercise, akin to pharmacological interventions, can regulate p53 expression and prevent cardiomyocyte death.

Regarding ATR, aerobic exercise attenuated DOX-induced increases. ATR plays a dual role in response to DNA damage: Facilitating DNA repair while, when overactivated, potentially leading to cell cycle arrest and apoptosis (30). Exercise appears to modulate DDR intensity, balancing DNA repair and apoptosis prevention, which may explain the concurrent reduction of ATR and improvement in apoptotic indices (p53) observed in this study.

Despite physiological differences between swimming and treadmill exercise, no significant differences in the expression of the investigated genes were observed between the two modalities. This may reflect shared metabolic adaptations that enhance antioxidant capacity and mitochondrial function. Nonetheless, some studies suggest swimming may more effectively reduce oxidative cardiac stress (31), whereas treadmill exercise may exert stronger effects on functional cardiac indices (27), indicating potential subtle molecular or physiological differences not captured in this study.

Collectively, these findings underscore aerobic exercise as a non-pharmacological strategy to mitigate DOX-induced cardiotoxicity. Considering the limitations cancer patients often face during DOX treatment, exercise interventions may serve as valuable components of rehabilitation and preventive programs. Future studies should simultaneously examine molecular markers (ATR, p53) and functional cardiac pathways, and explore potential differences among exercise types using longer-term and varied-intensity protocols.

The present study demonstrates that aerobic exercise, particularly interval training, mitigates DOX-induced cardiotoxicity by downregulating ATR/p53-mediated DNA damage pathways. Our findings align with previous studies showing that exercise training exerts antioxidant and anti-apoptotic effects through modulation of mitochondrial dynamics and DNA repair mechanisms. Consistent with previous reports (21, 22, 32), aerobic training may activate convergent protective signaling pathways that suppress cell death responses to oxidative injury.

5.1. Conclusions

Doxorubicin administration significantly increased ATR and p53 expression in rat cardiac tissue, and these alterations were markedly attenuated by aerobic exercise. Both treadmill and swimming exercise effectively mitigated DOX-induced adverse effects, with no significant differences observed between the two modalities. These findings suggest that regular aerobic activity, regardless of type, may serve as an effective non-pharmacological intervention to reduce DOX-induced cardiotoxicity.

5.2. Study Limitations

This study was conducted in male mice only, which may limit generalizability to females or humans. Additionally, functional cardiac assessments (e.g., echocardiography) were not performed, and the focus was on molecular markers. Future studies should include both sexes and integrate functional and histological analyses to enhance translational relevance.