1. Background

Inflammation is often treated using NSAIDs and corticosteroids; however, long-term use of these drugs can lead to serious side effects such as gastrointestinal ulcers, kidney damage, and immune suppression (1-3). Due to these risks, there is growing interest in plant-based alternatives that may offer similar benefits with fewer adverse effects. Avicennia marina, a mangrove plant rich in flavonoids and phenolic compounds, has shown promising anti-inflammatory and antioxidant activities. In cell-based studies, A. marina extracts have reduced the release of inflammatory cytokines in immune cells (4). In animal models, oral doses of 200 - 400 mg/kg reduced joint swelling and inflammatory markers in arthritis (5), and improved liver function and oxidative stress in diabetic rats (6). However, few studies have explored its effects in acute inflammation, especially using dose–response designs in models like carrageenan-induced paw edema. This study addresses this gap by testing A. marina extract at 200, 400, and 600 mg/kg in a standard acute inflammation model.

2. Objectives

This study aims to evaluate the anti-inflammatory effects of the hydroalcoholic extract of A. marina in a carrageenan-induced paw edema model in male Albino Wistar rats. The objective is to determine the dose-dependent efficacy of the extract in reducing inflammation and compare its effects with the standard anti-inflammatory drug indomethacin, providing a scientific basis for its traditional use.

3. Methods

3.1. Plant Collection and Extraction

Samples of A. marina leaves were collected from the mangrove forests in Bushehr province. After identifying the plant and obtaining a herbarium voucher code, approximately 200 g of the leaves were extracted using 80% ethanol by the maceration method. This extraction process was repeated at least three times. To increase the concentration of polar compounds, defatting was carried out in several stages using n-hexane as the solvent (7). The extract was fully dried to eliminate residual ethanol, so a separate vehicle control was not used. Including a vehicle control group is recommended in future studies to rule out solvent effects.

3.2. Isolation Procedure

To provide a comprehensive explanation of the maceration method, the hydroalcoholic extract of A. marina leaves was prepared using the maceration method. Freshly collected leaves were washed, air-dried in a shaded area at room temperature, and ground into a fine powder. Approximately 200 g of this powder was soaked in 80% ethanol (v/v) in a ratio of 1:10 (w/v) at room temperature. The mixture was stirred intermittently and allowed to macerate for 72 hours. After this period, the extract was filtered through Whatman No. 1 filter paper, and the residue was re-extracted under the same conditions twice to ensure maximum extraction of bioactive compounds. The combined filtrates were concentrated under decreased pressure using a rotary evaporator at 40°C until a semi-solid crude extract was obtained (6).

3.3. Determination of Phenolic Content by the Folin-Ciocalteu Method

To determine the phenolic content of the extracts, the Folin-Ciocalteu reagent was used. Gallic acid was used as a standard polyphenol to create a calibration curve. For this, 1 mL of different concentrations of gallic acid solution (25, 50, 75, 100, 125, and 150 mg/L) was mixed with 5 mL of 10% Folin-Ciocalteu reagent and incubated at room temperature (25°C). After 10 minutes, 4 mL of 7.5% sodium bicarbonate solution was added, and the mixture was incubated for 60 minutes at room temperature, away from light. After blanking the UV spectrophotometer at 760 nm, the absorbance of each gallic acid sample was measured. This test was repeated three times for each concentration, and based on the results, a calibration curve of gallic acid (absorbance vs. concentration) was created. The same procedure was applied to the extracts. Finally, the phenolic content was reported as milligrams of gallic acid equivalent per gram of extract (8).

3.4. Determination of Total Flavonoid Content

The total flavonoid content was determined using the aluminum chloride colorimetric method, with quercetin as the standard. For this, 1 mL of quercetin solution (at concentrations of 20, 40, 60, 80, and 100 µg/mL) was mixed with 4 mL of distilled water and 0.3 mL of 5% sodium nitrite. After 5 minutes, 0.5 mL of 10% aluminum chloride was added, and the mixture was incubated at room temperature for another 5 minutes. Then, 2 mL of 1 M sodium hydroxide was added, and the volume was adjusted to 10 mL with distilled water. The UV spectrophotometer was zeroed at a wavelength of 510 nm using a blank, and the absorbance of the samples was measured. This procedure was repeated three times for each concentration, and a calibration curve was generated based on the results. The same procedure was applied to the extracts. Finally, the flavonoid content was expressed as milligrams of quercetin equivalent per 100 g of extract (9).

3.5. Animal Studies

3.5.1. in vivo Anti-Inflammatory Assay

Male Albino Wistar rats (200 - 250 g) were randomly divided into five groups of six animals each. Groups 1 - 3 received A. marina extract at doses of 200, 400, and 600 mg/kg, respectively. The positive control group (group 4) was treated with 10 mg/kg of the NSAID indomethacin, while the negative control group (group 5) received an equivalent volume of normal saline. Inflammation was induced by a subcutaneous injection of 100 µL of 1% carrageenan solution into the plantar surface of the paw. Paw volume was measured at baseline (time 0) and at 1, 2, 3, 4, and 5 hours post-carrageenan injection using a plethysmometer. The change in paw volume relative to baseline was used to evaluate the anti-inflammatory activity (5, 10, 11). Randomization was conducted using a simple random method to assign rats to treatment groups. The investigator responsible for paw volume measurement and biochemical assays was blinded to the group allocations to minimize measurement bias.

3.6. Dosage Justification

We chose 200, 400, and 600 mg/kg based on both efficacy and safety data from prior studies. Doses of 200 and 400 mg/kg were most effective in chronic models — reducing paw swelling and cytokines in adjuvant-induced arthritis (5) and improving oxidative markers in diabetic liver injury (6). The upper limit of 600 mg/kg remains well below reported acute LD50 values (> 8 g/kg) for A. marina extracts in rodents (12), ensuring a wide therapeutic window. Moreover, 400 mg/kg corresponds to the midpoint of the effective range, allowing dose–response evaluation for both sub-maximal and near-maximal anti-inflammatory effects in an acute carrageenan model. These data-driven doses thus provide a robust framework to assess potency, safety, and mechanism in our acute inflammation assay.

3.7. Blood Sampling and Serum Preparation

Blood samples were collected 5 hours after carrageenan injection, immediately following the final paw volume measurement. Under deep ether anesthesia, approximately 1.0 mL of blood was obtained via cardiac puncture using a sterile syringe and needle. The blood was transferred into plain microtubes and allowed to clot at room temperature for 30 minutes. Samples were then centrifuged at 3000 rpm for 20 minutes at 4°C (Hettich, Germany), and the serum was carefully separated and stored at -20°C until biochemical analysis (13).

3.8. Lipid Peroxidation Study

Serum malondialdehyde (MDA) levels were measured using the thiobarbituric acid reactive substances (TBARS) assay as described by Kei (1978). Briefly, 100 µL of serum was mixed with 200 µL of 20% (w/v) trichloroacetic acid and 100 µL of 0.375% (w/v) thiobarbituric acid. The mixture was incubated in a boiling water bath for 15 minutes, then cooled and centrifuged (Hettich, Germany) at 5000 rpm for 10 minutes. The absorbance of the resulting supernatant was measured at 532 nm using a spectrophotometer (BioTek SP2, USA). The MDA concentrations were calculated based on a standard curve prepared from 1,1,3,3-tetramethoxypropane and expressed as nmol/ml of serum (14).

3.9. Measurement of IL-6

Serum IL-6 levels were measured using a commercial ELISA kit (Catalogue No. SL0411Ra; SunLong Biotech Co., Ltd, China) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The assay range was 8 - 150 ng/L. Blood samples were collected 5 hours after treatment, centrifuged at 3000 rpm for 20 minutes (Hettich, Germany), and the serum was stored at -20°C until analysis (15). The results of paw edema were expressed as the change in paw volume at each time point relative to the baseline volume recorded at time zero.

4. Results

4.1. Evaluation of Phenolic Content

The total phenolic content of the extracts was quantified using the Folin-Ciocalteu method. The calibration curve for gallic acid demonstrated a linear correlation between absorbance and gallic acid concentration (R2 = 0.9816). Using this calibration curve, the phenolic content of the extracts was calculated and expressed as milligrams of gallic acid equivalents per gram of extract (mg GAE/g). The phenolic content of the extracts was determined to be 27 mg GAE/g, suggesting a significant concentration of phenolic compounds within the extracts.

4.2. Evaluation of Flavonoid Content

The flavonoid content of the A. marina plant sample was calculated to be 36.7 mL of rutin equivalent per gram of extract (mg QE/g) based on the calibration curve. The total flavonoid content of the extracts was determined using the aluminum chloride colorimetric method, with rutin as the standard. The calibration curve showed a strong linear relationship between rutin concentration and absorbance (R2 = 0.9985). Using this curve, the flavonoid content of the extracts was calculated and expressed as milligrams of rutin equivalent per gram of extract (mg QE/g). The total flavonoid content of the extract was found to be 36.7 mg QE/g, indicating a high concentration of flavonoids in the extract.

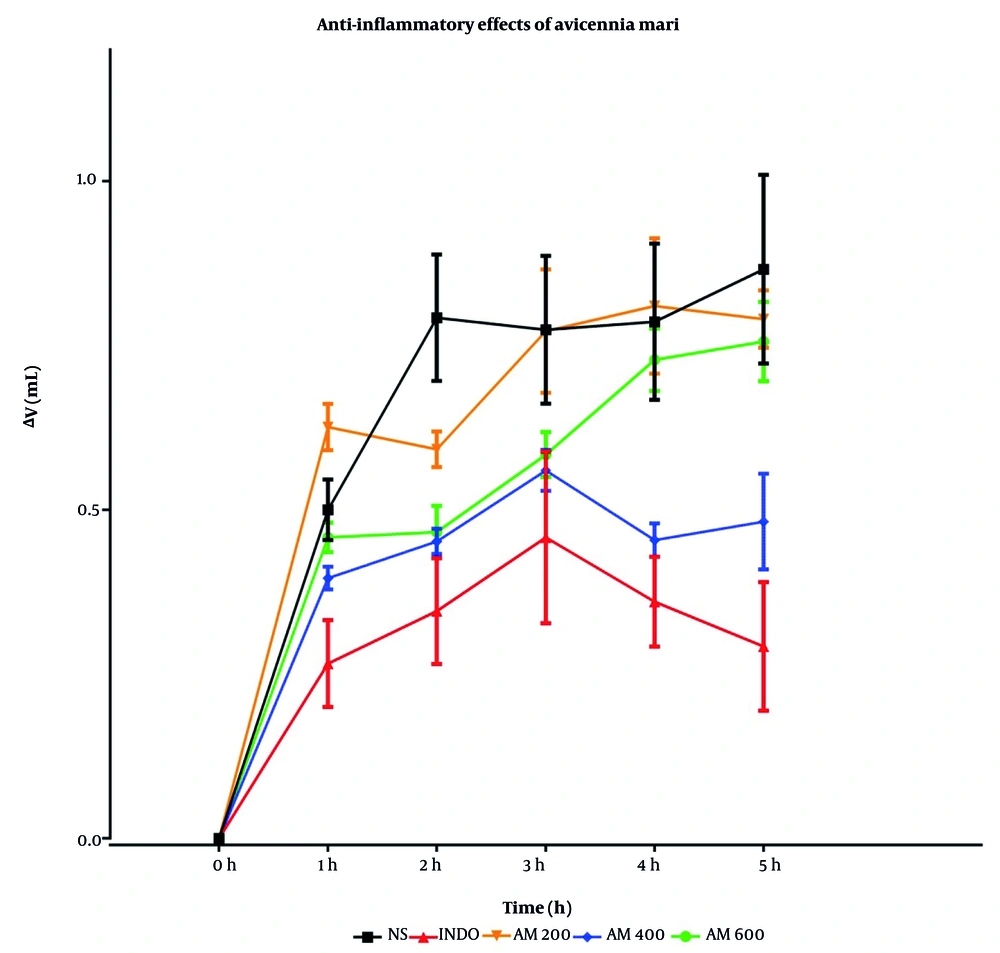

4.3. Evaluation of Mean Changes in Rat Paw Volume in Experimental Groups

After preparation of the A. marina extract, different doses of the extract, indomethacin, and normal saline were administered intraperitoneally to groups of six male rats. Half an hour later, a 1% carrageenan solution was injected subcutaneously into the plantar surface of the rats' paws. Paw volume changes were measured using a plethysmometer at 20-minute intervals during the first hour (and averaged) and then at 2, 3, 4, and 5 hours, as shown in Table 1 and Figure 1. Therefore, time zero in the graphs corresponds to the carrageenan injection time, as shown in Figure 1.

Comparison of the anti-inflammatory effects of hydroalcoholic extract of Avicennia marina (200, 400, and 600 mg/kg) with groups receiving normal saline (5 mL/kg) and indomethacin (10 mg/kg) via intraperitoneal administration; inflammation was induced using carrageenan (n = 6). (Abbreviations: NS, normal saline; INDO, indomethacin; AM, A. marina extract)

The changes in paw volume (mL) were measured 1 - 5 hours post subcutaneous injection of carrageenan following intraperitoneal injection of indomethacin (10 mg/kg), A. marina extract (200, 400, and 600 mg/kg), and normal saline (5 mL/kg), as shown in Table 1 and Figure 1.

| Hours | Normal Saline | Indomethacin | Avicennia marina (200 mg/kg) | Avicennia marina (400 mg/kg) | Avicennia marina (600 mg/kg) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 h | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 1 h | 0.50 ± 0.04 | 0.26 ± 0.07 | 0.62 ± 0.03 # | 0.39 ± 0.02 | 0.45 ± 0.02 |

| 2 h | 0.79 ± 0.09 | 0.34 ± 0.08 *** | 0.59 ± 0.03 | 0.45 ± 0.02 * | 0.46 ± 0.04 |

| 3 h | 0.77 ± 0.11 | 0.45 ± 0.13 | 0.77 ± 0.09 | 0.56 ± 0.03 | 0.58 ± 0.03 |

| 4 h | 0.78 ± 0.12 | 0.36 ± 0.07 ** | 0.81 ± 0.10 ### | 0.45 ± 0.02 # | 0.72 ± 0.05 ## |

| 5 h | 0.86 ± 0.14 | 0.29 ± 0.09 *** | 0.79 ± 0.04 ### | 0.48 ± 0.07 ** | 0.75 ± 0.06 ### |

a Values are expressed as mean ± SD.

b Significant difference compared to the normal saline group (*: P < 0.05, **: P < 0.01, ***: P < 0.001)

c Significant difference compared to the indomethacin group (#: P < 0.05, ##: P < 0.01, ###: P < 0.001).

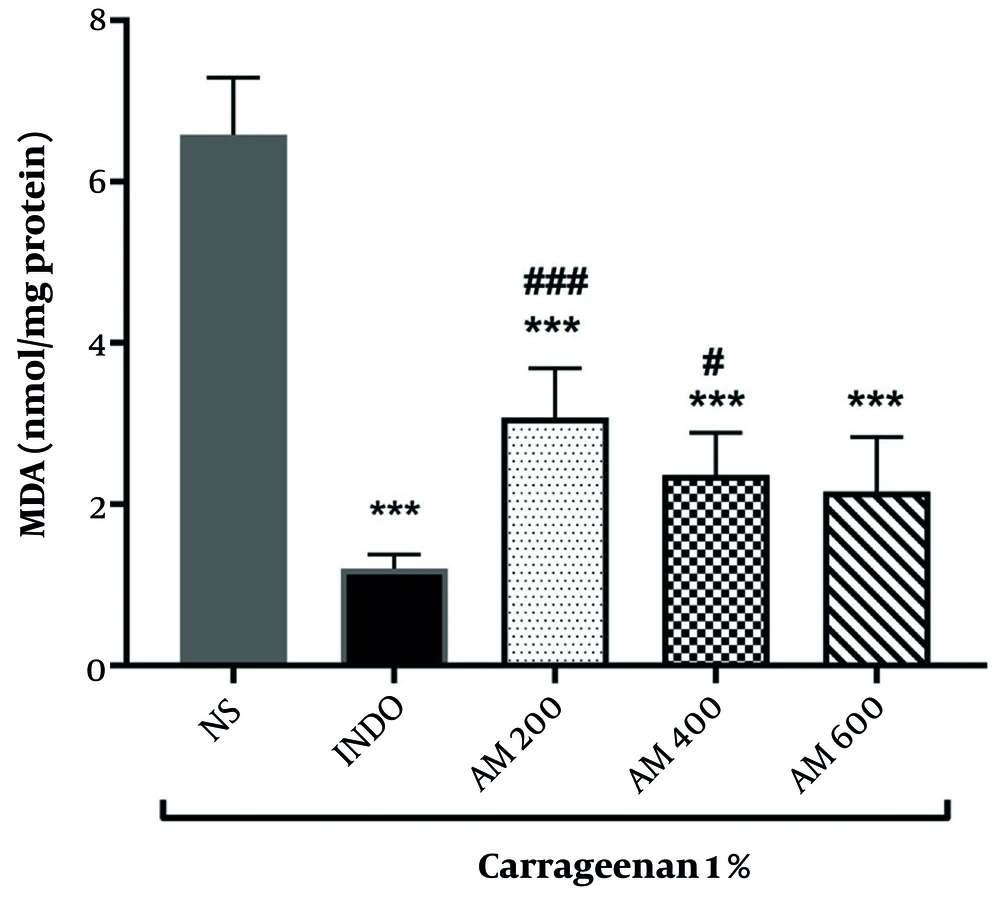

4.4. Evaluation of Malondialdehyde Levels in Rat Paw Serum in Experimental Groups

The results of MDA measurement in different groups are presented in Figure 2. The findings showed that indomethacin administration significantly decreases MDA levels compared to the normal saline group (P < 0.001).

Mean malondialdehyde (MDA) levels in rat paw tissue across experimental groups (significant difference compared to the normal saline group, *** P < 0.001; significant difference compared to the indomethacin group, # P < 0.05 and ### P < 0.001). (Abbreviations: NS, normal saline; INDO, indomethacin; AM, Avicennia marina extract)

The administration of the hydroalcoholic extract of A. marina at doses of 200, 400, and 600 mg/kg decreases MDA levels in rat paw serum compared to the normal saline group, indicating the extract's efficacy in decreasing oxidative damage induced by carrageenan injection. This reduction was significant at all extract doses (P < 0.001). Additionally, the MDA levels in groups receiving 200 and 400 mg/kg of the hydroalcoholic extract of A. marina were significantly different from the indomethacin group (P < 0.001 and P < 0.05, respectively). However, no statistically significant differences were observed between the groups receiving different doses of the extract.

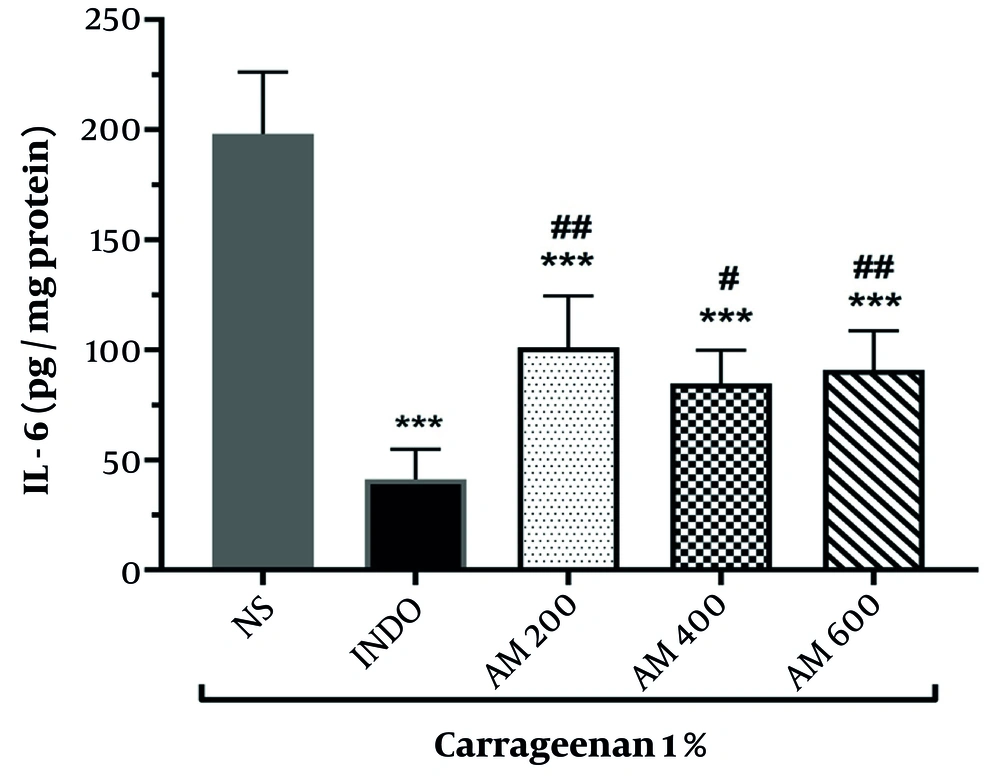

4.5. Measurement of IL-6 Levels in the Paws of Mice Across the Study Groups

The results of IL-6 measurements in different groups are presented in Figure 3. The findings demonstrated that indomethacin administration significantly decreases IL-6 levels compared to the normal saline group (P < 0.001).

Administration of the hydroalcoholic extract of A. marina at doses of 200, 400, and 600 mg/kg also significantly decreased IL-6 levels in rat paw serum compared to the normal saline group (P < 0.001), highlighting the extract’s anti-inflammatory effects against carrageenan-induced inflammation. Furthermore, IL-6 levels in groups receiving 200, 400, and 600 mg/kg of the hydroalcoholic extract of A. marina showed significant differences when compared to the indomethacin group (P < 0.01, P < 0.05, and P < 0.01, respectively). No statistically significant differences were observed among the groups receiving different doses of the extract.

5. Discussion

This study primarily focused on IL-6 and MDA as key markers of inflammation and oxidative stress. Although TNF-α and IL-1β were not directly measured in this acute model, their modulation by A. marina has been demonstrated in previous studies using chronic inflammation models. For instance, Zamani Gandomani and Forouzandeh Malati reported that oral administration of A. marina extract at doses of 200 and 400 mg/kg significantly reduced ankle swelling and normalized serum IL-1β, IL-6, and TNF-α levels in rats with adjuvant-induced arthritis. Notably, the 400 mg/kg dose produced the most substantial cytokine reduction, which aligns with the optimal dose observed in our current model (5). Similarly, Sadoughi and Hosseini demonstrated a dose-dependent decrease in TNF-α, IL-1β, and IL-6 levels in type 1 diabetic rats treated with A. marina extract at 100 and 200 mg/kg, along with improvements in oxidative stress markers and liver histology (6).

Studies in both arthritis and diabetes models suggest that the potent anti-inflammatory effects of A. marina are primarily attributed to its high phenolic and flavonoid content. These compounds modulate key intracellular signaling pathways responsible for inflammation. Specifically, they inhibit the NF-κB signaling pathway — a central regulator of pro-inflammatory gene expression — by preventing the phosphorylation and nuclear translocation of the p65 subunit (4, 11). Concurrently, they suppress the MAPK cascade (including JNK, ERK, and p38), which contributes to the amplification of inflammatory and oxidative signals (16). Through this dual inhibition of NF-κB and MAPK pathways, A. marina reduces the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines and limits the generation of reactive oxygen species (ROS), thereby alleviating tissue damage and edema (16, 17). Given these mechanisms, A. marina may also offer therapeutic value in other inflammation-related diseases such as sickle cell disease, where oxidative stress and vascular inflammation play central roles in disease progression (18).

In summary, our findings not only support previous studies by confirming the extract’s ability to reduce oxidative stress (as indicated by MDA) and inflammatory cytokine levels in chronic and metabolic disease models but also extend the current understanding by demonstrating its efficacy in an acute inflammation model (19, 20). Although intraperitoneal administration was chosen for better experimental control, oral delivery should be evaluated in future studies for clinical relevance.

These collective data reinforce the therapeutic potential of A. marina as a plant-based anti-inflammatory agent with multi-targeted efficacy across diverse pathological conditions. Similar anti-inflammatory outcomes have also been reported using other natural extracts in carrageenan-induced inflammation models. For example, recent findings show that certain lichen species significantly reduced paw edema in rats, demonstrating comparable effects to indomethacin in acute inflammation (21). Although the current study focused on in vivo evaluation, future research should incorporate in vitro assays using immune cell models to better elucidate the specific molecular pathways modulated by the extract. Such studies will further clarify the mechanisms underlying its anti-inflammatory effects and may guide the development of targeted phytotherapeutic agents. However, the small sample size, while acceptable for an exploratory study, may have limited the ability to detect subtle differences between extract dosages. Larger studies are needed to confirm the observed trends.

Overall, the results of this study show that A. marina has strong anti-inflammatory effects. The extract was able to reduce swelling in the paw and lower important inflammatory markers like IL-6 (22). It also reduced oxidative stress, which plays a key role in worsening inflammation (23). These effects are likely related to the plant’s natural compounds, such as flavonoids and phenolic substances, which can block important signaling pathways like NF-κB and MAPK that usually increase inflammation in the body (24). Since the extract worked well in an acute inflammation model, it might also be useful for other inflammatory conditions in the future. Natural treatments like this are especially valuable because many synthetic anti-inflammatory drugs can cause side effects when used long-term (25). Therefore, more research is needed to understand exactly how A. marina works, which compounds are responsible for its effects, and whether it can be used safely and effectively in humans. This study provides a useful first step in exploring the medical benefits of this plant and supports its potential as a natural option for controlling inflammation.

5.1. Conclusions

The hydroalcoholic extract of A. marina with 400 mg/kg showing the most consistent reduction across all markers, carrageenan-induced paw edema, MDA, and IL-6 levels in rats. Although indomethacin exhibited superior efficacy, A. marina showed meaningful anti-inflammatory activity with a potentially better safety profile. Notably, in addition to its effectiveness in acute inflammation, previous evidence highlights its therapeutic potential in chronic inflammatory models as well, reinforcing its relevance as a dual-action, plant-based alternative to conventional NSAIDs. Further studies are warranted to better elucidate its mechanisms and support clinical translation.