1. Background

Complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) refers to a broad range of health practices and systems not typically included in conventional medicine. While modern biomedical knowledge is grounded in empirical evidence and validated through rigorous experimentation, CAM often relies on diverse theories and practices that lack sufficient scientific scrutiny to conclusively establish their safety and efficacy (1).

A hallmark of CAM is its holistic, patient-centered philosophy that prioritizes internal healing processes and emphasizes psychological and emotional well-being. Proponents argue that the human body possesses innate mechanisms for maintaining health and combating illness (2). The CAM interventions seek to activate these capabilities by aligning therapeutic efforts with patients' lifestyle, diet, physical activity, and stress levels. The therapeutic alliance — defined by trust and collaboration between patient and practitioner — is central to CAM care (3).

Increasingly, cancer patients are drawn to CAM for its perceived naturalness, minimal invasiveness, and personalized approach. Multiple studies indicate that between 56% and 72% of individuals undergoing cancer treatment use CAM concurrently with conventional therapies (4, 5). In Australia, estimates suggest that between 17% and 87% of cancer patients engage in at least one type of CAM (6). Motivations include the desire to manage treatment side effects, enhance quality of life, and address dissatisfaction with conventional medical care — especially in cases involving high toxicity or limited efficacy (7).

To address the proliferation of CAM use, the United States National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health (NCCIH) has initiated research using controlled methodologies to evaluate the effectiveness and safety of these practices. The NCCIH classifies CAM into five major categories: Alternative medical systems, mind-body interventions, biologically based therapies, manipulative techniques, and energy therapies (8). Of these, herbal medicine plays a particularly prominent role in both traditional and modern applications. With growing interest in plant-derived compounds for 21st-century pharmacology, researchers are increasingly focused on the clinical implications of phytotherapy.

According to the World Health Organization (WHO), over 80% of the global population relies on medicinal plants for primary healthcare needs. However, only around 200 species are routinely used in medical practice, and fewer than one-third are recognized for standardized medicinal properties (9). The WHO has consistently advocated for the responsible integration of herbal medicine into public health strategies, formally recognizing its role in national systems as early as 1987 (10).

Cancer patients often utilize CAM approaches alongside conventional treatments, motivated by goals such as alleviating adverse effects, slowing disease progression, preventing metastasis, or seeking a cure (11-13). Recent systematic reviews (11-13), including a 2023 study, have reinforced this trend that CAM use among cancer patients remains widespread, with over 50% prevalence globally, and highlighted the need for improved communication between patients and healthcare providers (12). Another 2024 study revealed that 41% of Dutch cancer patients used CAM while receiving anticancer treatment, and 10% experienced clinically relevant drug-herb interactions, underscoring the importance of routine screening and disclosure (13). Furthermore, evidence from a 2023 narrative review supports the role of mind-body therapies — such as meditation, yoga, and hypnosis — in improving depression, fatigue, and immune function among oncology patients (12).

Despite extensive global research, CAM use among Iranian cancer patients remains underexplored. In Iran, traditional herbal remedies are deeply embedded in cultural and religious practice, readily accessible through Attari shops and informal vendors. However, little data exists regarding clinical safety, particularly the potential for drug-herb interactions, which may compromise oncology care (14). Cultural beliefs, lack of patient-provider communication, and unregulated access pose unique challenges within this context.

2. Objectives

This study aims to address this critical gap by assessing the prevalence, patterns, motivations, and safety considerations — including interaction risks — of CAM use among Iranian cancer patients.

3. Methods

This study utilized a prospective cross-sectional, descriptive-analytical design to examine the frequency and usage patterns of CAM and medicinal herbs, alongside assessing potential drug interactions caused by herbal remedies in cancer patients referred to Omid Hospital in Isfahan, Iran, during 2019.

Omid Hospital serves as a tertiary, university-affiliated center specializing in the treatment of cancer and its associated complications. Participants included both metastatic and non-metastatic cancer patients recruited from specialized cancer hospitals, oncology departments within general hospitals, outpatient day clinics, and radiotherapy centers. All patients were provided with detailed information about the study prior to participation.

Eligibility criteria required that participants be Persian-speaking adults of any gender with a confirmed cancer diagnosis. They had to be aware of their diagnosis and either undergoing anticancer treatment — such as antiblastic chemotherapy, endocrine therapy, radiotherapy, or surgery — at the time of the survey, or have completed such treatment within the preceding three years. Additional requirements included the ability to comprehend the survey questions, absence of any condition that would render questionnaire completion inappropriate or excessively burdensome, and a willingness to participate in the study. Patients unwilling to participate or without a history of CAM usage were excluded. Ethical approval for the research was granted by the Ethics Committee (ID: IR.MUI.RESEARCH.REC.1398.359), and all enrolled participants provided written informed consent at the start of data collection.

3.1. Data Collection

In this study, CAM was defined according to the NCCIH (15) as medical products and practices that are not part of standard medical care. This encompasses herbal remedies, spiritual healing practices such as prayer, recitation of religious texts or spiritual rituals, traditional Persian medicine, and other culturally embedded therapies commonly used in Iran.

Patients were selected through simple random sampling from oncology clinics, including both inpatient and outpatient settings. Eligible individuals were those with a confirmed cancer diagnosis who had visited the clinic within a specified timeframe. Participants were invited to complete a structured checklist administered by trained researchers, either during treatment sessions or follow-up visits. Patients completed the checklist with the assistance of an investigator, ensuring clarity and support throughout the process. The checklist was administered to patients after they received detailed information about the study, provided informed consent, and signed the consent form. Completion of the checklist was voluntary and did not interfere with medical treatment.

Before final patient sampling, researchers conducted one-on-one introductions with all patients, aligning with a strategy to minimize sampling errors. During this process, the project title was not disclosed; instead, a general discussion on the study topic was initiated. Patients willing to participate received further information about the study, including detailed explanations of CAM concepts and objectives. Data was gathered through private interviews conducted by a trained student researcher using pre-designed forms adapted from prior studies (5). To maintain privacy during interviews, sessions were held in private spaces, each lasting approximately 10 - 15 minutes. To enhance accuracy, responses were cross-checked with participants. However, we acknowledge the potential for self-reporting bias, which may affect the reliability of reported data due to recall errors or personal biases. Efforts to minimize this included training the student researcher to probe for consistent responses and providing clear instructions to participants. The student researcher also extracted disease-related information from patient medical records available in hospital wards or clinics. Training sessions focused on interview techniques and clinical data extraction ensured the quality and consistency of this process.

3.2. Complementary and Alternative Medicine Data Collection Description

Data collection was conducted over several months, with researchers present at least three days per week to ensure consistent engagement. Patient information was gathered through interviews and medical records, including treatment charts and medication histories.

For data collection, a standardized checklist was employed to achieve the study's objectives. It featured two main sections: Demographic and social characteristics (e.g., age, sex, marital status, education level, occupation, income) and questions related to CAM usage.

To assess the use of CAM among participants, we utilized the International Questionnaire to Measure Use of Complementary and Alternative Medicine (I-CAM-Q), a standardized instrument originally developed by Quandt et al. (16) and later translated and culturally adapted into Farsi by Rostami Chijan et al. (17) for use in Iranian populations. The Farsi version, known as I-CAM-IR, was designed to capture culturally relevant CAM practices and terminology, including references to traditional Persian medicine. The questionnaire covers several key domains: Types of CAM therapies used (such as herbal remedies, acupuncture, and yoga), frequency and duration of use, motivations for CAM use (e.g., symptom management or general wellness), sources of recommendation (including healthcare professionals, family members, or media), perceived effectiveness and satisfaction with CAM modalities, and whether CAM use was disclosed to conventional healthcare providers. This comprehensive tool enabled systematic and culturally sensitive data collection on CAM usage patterns within the study population. The data checklist also included specific items asking patients to list any prescription medications they were taking alongside herbal remedies.

Psychological distress was assessed using the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) (18), a validated self-report instrument designed to detect states of anxiety and depression in patients with physical health conditions. The HADS consists of 14 items, divided equally into two subscales: Anxiety (HADS-A) and depression (HADS-D). Each item is scored on a 4-point Likert scale (0 - 3), yielding subscale scores ranging from 0 to 21. Scores were interpreted as follows: Zero - seven indicating mild symptoms, 8 - 10 moderate, and 11 - 21 severe. Participants completed the Farsi version of the HADS Questionnaire (19) just before the interview during their clinical visit, and responses were analyzed to determine the prevalence and severity of anxiety and depression within the study.

Logistic regression was employed to assess the likelihood of CAM use based on various demographic and clinical predictors. We conducted both univariate and multivariate logistic regression analyses to examine the associations between these factors and the utilization of four major CAM categories among Iranian cancer patients: (1) Commonly used herbs, (2) mental methods such as prayer and spiritual healing, (3) alternative medicine including homeopathy, and (4) other traditional practices such as sacrifice, special diets, and blood cupping.

3.3. Drug-Herb Interaction

Patients were asked about their use of prescription medications and potential interactions through structured interviews conducted by trained researchers. These interviews typically involved the use of standardized checklists or semi-structured questionnaires designed to capture detailed information on all medications currently being taken, including prescription drugs, over-the-counter products, and herbal supplements. To ensure clarity and completeness, interviewers probed for specific drug names, dosages, frequency of use, and any concurrent use of herbal remedies. Patients were also asked whether they had experienced any side effects or changes in treatment efficacy that might suggest an interaction.

To evaluate potential drug-herb interactions among cancer patients, the study utilized a structured checklist and cross-referenced responses with established pharmacological databases and peer-reviewed literature (20, 21). This approach enabled the identification of commonly reported drug-herb combinations and assessment of possible interaction mechanisms, including pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic effects. Data were collected during patient interviews and supplemented by medical record reviews to enhance accuracy and contextual relevance.

3.4. Statistical Approaches

3.4.1. Sample Size Calculation

The sample size was determined using a standard formula based on a 95% confidence level and a 5% margin of error, resulting in a target of approximately 400 participants. To estimate the sample size, the following formula was employed:

In which N represents the sample size, Z is the reliability coefficient (80%), p1 is the probability observed in a similar study (52%, based on Jermini et al. (5), and d is the allowable margin of error.

3.4.2. Data Analyses

The descriptive analysis incorporated the use of median values, ranges, and relative frequency distributions. Frequency analysis and cross-tabulations were performed using chi-square (χ2) tests. Logistic regression was employed to assess the likelihood of CAM use based on various demographic and clinical predictors. We conducted both univariate and multivariate logistic regression analyses to examine the associations between these factors and the utilization of four major CAM categories among Iranian cancer patients. Univariate models were used to identify individual predictors of CAM use, while multivariate models adjusted for potential confounders to determine independent associations. Odds ratios (ORs) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were calculated for each variable, and statistical significance was defined as a P-value less than 0.05. All analyses were performed using Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) version 23.

4. Results

The study population consisted of 400 individuals, with a slight male predominance (54%). The majority of participants were aged between 60 and 80 years (43.75%), reflecting an older demographic profile. Educational attainment varied, with most individuals holding a diploma (29%) or bachelor's degree (22.5%). Marital status was predominantly married (77.5%). A substantial proportion of participants reported underlying health conditions, notably hypertension (21%) and cardiovascular disease (19.25%). Most patients were diagnosed with non-metastatic cancer (75.75%) and had been receiving treatment for 1–3 years (52.25%). Skin (20.75%), breast (18.75%), and colorectal (14.75%) cancers were the most prevalent tumor types. Psychological assessment revealed that 44% of participants experienced severe anxiety, while 60% reported mild depressive symptoms, indicating a significant mental health burden within this population. Baseline, clinical, and socioeconomic characteristics of patients have been summarized in Table 1.

| Characteristics | No. (%) |

|---|---|

| Sex | |

| Male | 216 (54) |

| Female | 184 (46) |

| Median age (y) | |

| Range 0 - 20 | 13 (3.25) |

| 21 - 40 | 41 (10.25) |

| 41 - 60 | 115 (28.75) |

| 60 - 80 | 183 (43.75) |

| > 80 | 56 (14) |

| Education status | |

| No education | 7 (1.75) |

| Middle school diploma | 62 (15.5) |

| Diploma | 116 (29) |

| Associate degree | 68 (17) |

| Bachelor | 90 (22.5) |

| Master | 42 (10.5) |

| Doctoral | 15 (3.75) |

| Marital status | |

| Single | 40 (10) |

| Married | 310 (77.5) |

| Divorced | 29 (7.25) |

| Widowed | 21 (5.25) |

| History of underlying disease | |

| Hypertension | 84 (21) |

| CVD | 77 (19.25) |

| Chronic constipation | 57 (14.25) |

| Hypothyroidism | 42 (10.5) |

| Diabetes mellitus | 41 (10.25) |

| Pulmonary disease | 33 (8.25) |

| Hemorrhoids | 18 (4.5) |

| Chronic hepatitis | 15 (3.75) |

| Kidney stone | 13 (3.25) |

| Other diseases | 20 (5) |

| Cancer stage | |

| Metastatic | 97 (24.25) |

| Non-metastatic | 303 (75.75) |

| Duration of treatment (y) | |

| Less than 1 | 131 (32.75) |

| 1 - 3 | 209 (52.25) |

| More than 3 | 60 (10) |

| Time of diagnosis (y) | |

| Less than 1 | 101 (25.25) |

| 1 - 3 | 222 (55.5) |

| More than 3 | 77 (19.25) |

| Primary tumors | |

| Skin | 83 (20.75) |

| Breast | 75 (18.75) |

| Colorectal | 59 (14.75) |

| Hematological | 41 (10.25) |

| Gastric | 31 (7.75) |

| Prostate | 28 (7) |

| Bladder | 25 (6.25) |

| Brain | 22 (5.5) |

| Thyroid | 18 (4.5) |

| Others | 18 (4.5) |

| HADS anxiety score | |

| Severe | 176 (44) |

| Moderate | 76 (19) |

| Mild | 148 (37) |

| HADS depression score | |

| Severe | 60 (15) |

| Moderate | 100 (25) |

| Mild | 240 (60) |

Abbreviations: CVD, cardiovascular disease; HADS, The Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale.

Among the 400 participants, a variety of complementary and alternative products and practices were reported following cancer diagnosis. Analysis of medicinal plant usage at the onset of cancer showed that Mentha had the highest consumption rate (30%), followed by Salix aegyptiaca (Persian or Musk Willow) at 23.5%, and licorice at 22%. Prayer and spiritual healing were the most commonly adopted mental methods (188; 47%), followed by psychotherapy and counseling (34; 8.5%). Sacrificial rituals were practiced by 179 individuals (44.75%), and special diets were followed by 94 (23.5%). Bloodletting or blood cupping was used by 34 (8.5%), and votive offerings were reported by 25 (6.25%, Table 2).

| Products/Modalities | Patients |

|---|---|

| Commonly used herbs | |

| Musk willow | 94 (23.5) |

| Sisymbrium | 87 (21.75) |

| Orange blossom | 73 (18.25) |

| Thymus | 80 (20) |

| Mentha | 122 (30.5) |

| Liquorice | 88 (22) |

| Garlic | 40 (10) |

| Mental methods | |

| Prayer and spiritual healing | 188 (47) |

| Psychotherapy and counseling | 34 (8.5) |

| Meditation and yoga | 10 (2.5) |

| Witchcraft | 19 (4.75) |

| Alternative medicine | |

| Acupuncture | 20 (5) |

| Homeopathy | 116 (29) |

| Others | |

| Sacrifice | 179 (44.75) |

| Votive offerings | 25 (6.25) |

| Blood cupping | 34 (8.5) |

| Special diet b | 94 (23.5) |

a Values are expressed as No. (%).

b This diet includes nutritional therapy, slimming diets, etc.

Table 3 highlights the reasons and perceived benefits of CAM use among participants. Notably, 78.5% (314 patients) reported utilizing any method that could potentially assist in treating their disease, often supplementing conventional treatments with CAM. Meanwhile, 23% (92 participants) cited CAM’s perceived safety and its appeal as an alternative to chemotherapy's side effects. Another 10.25% opted for CAM due to dissatisfaction or lack of adequate response to conventional treatments, while 8.5% indicated alignment between CAM practices and their personal beliefs. A small proportion (only 3%) believed they could independently manage their care through CAM, and 1.25% chose CAM due to its less technological nature, fostering a closer relationship between patient and therapist.

| Factors | Patients |

|---|---|

| Reasons | |

| Desire to do everything possible to fight the disease | 314 (78.5) |

| Safety of complementary medicine | 92 (23) |

| To improve emotional well-being, provide hope, and increase optimism | 41 (10.25) |

| Match complementary medicine more with our thoughts and ideas | 34 (8.5) |

| Self-control treatment | 12 (3) |

| Improving the patient-therapist relationship | 5 (1.25) |

| Expected advantages | |

| To strengthen the fight against cancer | 254 (63.5) |

| To increase mental strength in the fight against cancer | 128 (32) |

| To increase the body’s ability to fight the cancer | 73 (18.25) |

| Improves cancer symptoms | 52 (13) |

| Directly improves treatment | 18 (4.5) |

| Improves the side effects of conventional cancer treatments | 14 (3.5) |

| To improve physical well-being | 12 (3) |

a Values are expressed as No. (%).

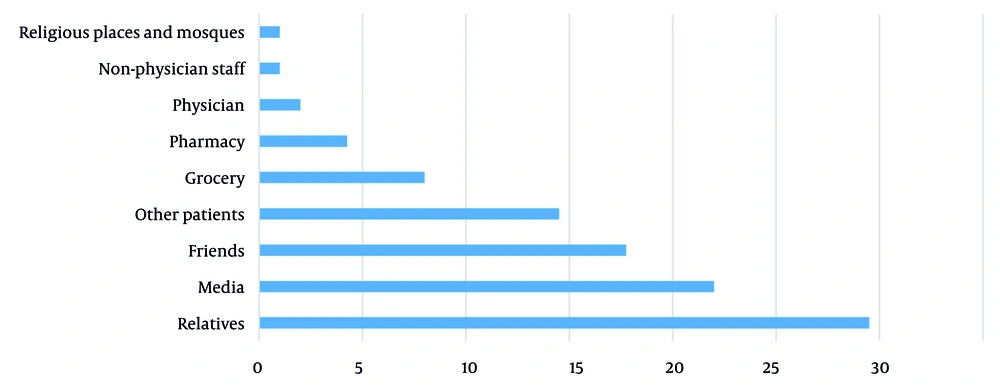

Despite widespread CAM use, 91.5% (366 patients) did not inform their physicians about concurrent CAM use alongside conventional medicine. Only 6.5% (26 participants) disclosed their CAM usage to their healthcare providers, while just 2% stated that their physician encouraged CAM adoption. Reasons for non-disclosure included physician recommendations to rely solely on conventional medicine (41%), the perception that physicians were skeptical about CAM (22.25%), the belief that discussing CAM was irrelevant to the treating physician (13.75%), and the view that sharing this information was unimportant (14.5%). Among those who communicated their CAM usage (8.5%), advice mainly came from relatives or various media sources (Figure 1). Pharmacies and perfumeries were also identified as significant CAM information resources.

As shown in Table 4, a total of 221 herb-drug interactions were identified among the 400 participants, involving various medicinal plants and pharmacological agents. The most frequently reported interactions were associated with increased bleeding risk, altered drug metabolism, and cardiovascular effects. For example, garlic interacted most frequently with aspirin (16; 7.24%) and warfarin (8; 3.62%), both leading to elevated international normalized ratio (INR) and increased bleeding risk. These kinds of interactions were primarily associated with garlic, ginkgo, curcumin, and their concurrent use with warfarin or aspirin.

| Medicinal Plants; Drugs/Pharmacological Classes | Consequence of Interaction | No. (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Garlic | ||

| Warfarin | Increase INR and risk of bleeding | 8 (3.62) |

| Aspirin | Increase INR and risk of bleeding | 16 (7.24) |

| Glibenclamide | Increase risk of hypoglycemia | 3 (1.35) |

| Losartan | Hypotension | 7 (3.17) |

| Curcumin | ||

| Warfarin | Increase INR and risk of bleeding | 12 (5.43) |

| Aspirin | Increase INR and risk of bleeding | 21 (9.50) |

| Ginkgo | ||

| Warfarin | Increase INR and risk of bleeding | 4 (1.81) |

| Aspirin | Increase INR and risk of bleeding | 6 (2.71) |

| Acetaminophen | Subarachnoid hemorrhage, hematoma | 3 (1.36) |

| Liquorice | ||

| Digoxin | Hypocalcemia, Digoxin toxicity | 2 (0.90) |

| Hydrochlorothiazide | Hypocalcemia, sodium retention, and high blood pressure | 7 (3.17) |

| Laxative | Risk of hypokalemia | 5 (2.26) |

| Antibiotics | Intestinal bacterial flora is inhibited by antibiotics and then the herb effect decreases. | 4 (1.80) |

| Fennel | ||

| ACEIs | Risk of increase in blood pressure | 6 (2.71) |

| TCAs | Risk of arrhythmia and high blood pressure | 2 (0.9) |

| β-blockers | Arrhythmia and high blood pressure | 9 (4.07) |

| Ginseng | ||

| Warfarin | Risk of bleeding time prolongation, drug antagonistic and decrease in INR | 3 (1.36) |

| Heparin | Risk of bleeding time prolongation, drug antagonistic and decrease in INR | 4 (1.81) |

| Antipsychotics | Risk of central nervous system stimulation, insomnia, headache and Tremor | 3 (1.36) |

| Digoxin | Increase in drug level and toxicity | 1 (0.45) |

| TCAs, MAOIs, and SSRIs | Increase in risk of serotonin syndrome | 5 (2.26) |

| Psyllium | ||

| Insulin | Decrease in drug level | 3 (1.36) |

| Iron | Decrease in iron absorption | 14 (6.33) |

| Valerian | ||

| Iron | Decrease in iron absorption | 17 (7.69) |

| β-blockers | Increasing valerian sedation effect | 7 (3.17) |

| Eucalyptus | ||

| All medications | Decrease in drug effect | 15 (6.79) |

| Alcea | ||

| All medications | Decrease in drug effect | 18 (8.14) |

| Ginger | ||

| H2-blockers | Increase in drug effect | 13 (5.88) |

| CCBs | Increase in calcium absorption, causes an increase or decrease in drug effect | 3 (1.36) |

Abbreviations: INR, international normalized ratio; ACEIs, angiotensin-converting-enzyme inhibitors; TCAs, tricyclic antidepressants; MAOIs, monoamine oxidase inhibitors; SSRIs, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors; CCBs, calcium channel blockers.

Table 5 presents the results of univariate and multivariate logistic regression analyses examining the association between demographic and clinical factors and the use of four major categories of CAM among Iranian cancer patients: Commonly used herbs, mental methods (e.g., prayer, spiritual healing), alternative medicine (e.g., homeopathy), and other practices (e.g., sacrifice, special diet, blood cupping).

| Variables | Crude | Adjust | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR | 95% CI (Lower - Upper) | P-Value | OR | 95% CI (Lower - Upper) | P-Value | |

| Commonly used herbs | ||||||

| Age | 0.817 | 0.70 - 0.954 | 0.011 | 0.358 | 0.216 - 0.593 | < 0.001 |

| Gender (male vs. female) | 57.71 | 17.83 - 186.740 | < 0.001 | 2.613 | 1.570 - 11.97 | 0.016 |

| Education level | 0.448 | 0.367 - 0.545 | < 0.001 | 0.193 | 0.106 - 0.353 | < 0.001 |

| Cancer stage (metastatic vs. non-metastatic) | 13.23 | 4.08 - 42.89 | < 0.001 | 14.77 | 2.99 - 72.89 | < 0.001 |

| Duration of treatment | 0.01 | 0.003 - 0.033 | < 0.001 | 0.030 | 0.010 - 0.034 | < 0.001 |

| Mental methods | ||||||

| Age | 0.873 | 0.747 - 1.021 | 0.088 | 0.939 | 0.687 - 1.284 | 0.694 |

| Gender (male vs. female) | 44.88 | 13.85 - 145.41 | < 0.001 | 1.125 | 0.493 - 2.569 | 0.780 |

| Education level | 0.548 | 0.455 - 0.660 | < 0.001 | 0.717 | 0.554 - 0.926 | 0.011 |

| Cancer stage (metastatic vs. non-metastatic) | 10.86 | 3.34 - 35.27 | < 0.001 | 0.071 | 0.011 - 0.449 | 0.005 |

| Duration of treatment | 0.005 | 0.001 - 0.020 | < 0.001 | 0.022 | 0.007 - 0.068 | < 0.001 |

| Alternative medicine | ||||||

| Age | 0.637 | 0.524 - 0.774 | < 0.001 | 0.738 | 0.523 - 1.042 | 0.084 |

| Gender (male vs. female) | 0.875 | 0.401 - 1.913 | 0.739 | 0.392 | 0.150 - 1.020 | 0.055 |

| Education level | 0.889 | 0.675 - 1.170 | 0.401 | 0.714 | 0.510 - 0.999 | 0.049 |

| Cancer stage (metastatic vs. non-metastatic) | 38.57 | 11.37 - 130.75 | < 0.001 | 13.74 | 2.048 - 92.27 | 0.007 |

| Duration of treatment | 0.065 | 0.016 - 0.269 | < 0.001 | 0.385 | 0.059 - 2.539 | 0.322 |

| Others | ||||||

| Age | 0.728 | 0.633 - 0.838 | < 0.001 | 0.821 | 0.558 - 1.208 | 0.317 |

| Gender (male vs. female) | 49.0 | 23.51 - 102.09 | < 0.001 | 12.45 | 5.137 - 30.20 | < 0.001 |

| Education level | 0.691 | 0.598 - 0.799 | < 0.001 | 0.513 | 0.355 - 0.741 | < 0.001 |

| Cancer stage (metastatic vs. non-metastatic) | 19.96 | 7.15 - 55.71 | < 0.001 | 2.434 | 0.419 - 14.14 | 0.322 |

| Duration of treatment | 0.034 | 0.017 - 0.071 | < 0.001 | 0.119 | 0.039 - 0.364 | < 0.001 |

Abbreviations: OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence interval.

In the adjusted model, several factors emerged as significant independent predictors of CAM use. Older age was negatively associated with the use of commonly used herbs [adjusted odds ratio (aOR) = 0.358, 95% CI: 0.216 - 0.593, P < 0.001], suggesting that younger patients were more likely to use herbal remedies. Similarly, a higher education level was linked to lower herb use (aOR = 0.193, 95% CI: 0.106 - 0.353, P < 0.001). Notably, male patients were significantly more likely than females to use herbs in univariate analysis (crude OR = 57.71), but after adjustment, this association was attenuated though still significant (aOR = 2.613, 95% CI: 1.570 - 11.97, P = 0.016). Patients with metastatic cancer were far more likely to use herbal remedies (aOR = 14.77, P < 0.001), and longer treatment duration was also strongly associated with herb use (aOR = 0.003, P < 0.001), indicating higher utilization over time.

Regarding mental methods, only education level remained a significant predictor after adjustment: Patients with higher education were less likely to use prayer or spiritual healing (aOR = 0.717, 95% CI: 0.554 - 0.926, P = 0.011). In contrast, having metastatic disease was no longer positively associated in the adjusted model; instead, it showed a strong inverse relationship (aOR = 0.071, P = 0.005), suggesting that non-metastatic patients were more likely to use mental CAM methods. Treatment duration remained significantly associated (aOR = 0.022, P < 0.001).

For alternative medicine (e.g., homeopathy), metastatic cancer was a strong independent predictor (aOR = 13.74, 95% CI: 2.05 - 92.27, P = 0.007), while a higher education level was negatively associated (aOR = 0.714, P = 0.049). Age and gender showed borderline significance after adjustment. Finally, in the "Others" category (including sacrifice, special diet, votive offerings), male gender was a strong independent predictor (aOR = 12.45, 95% CI: 5.14 - 30.20, P < 0.001), and higher education was protective (aOR = 0.513, P < 0.001). Longer treatment duration was also significantly associated with greater use (aOR = 0.119, P < 0.001).

In summary, this multivariate analysis reveals that younger age, male gender, lower education, metastatic disease, and longer treatment duration are key independent factors associated with increased use of specific CAM modalities, particularly herbal and ritual-based practices. These findings highlight the complex interplay between clinical status, sociodemographic factors, and patient choices in CAM utilization, underscoring the need for personalized, culturally informed communication in oncology care.

5. Discussion

This study provides a novel contribution by combining a culturally specific analysis of CAM usage with a focused evaluation of potential drug-herb interactions among Iranian cancer patients — an area that has been underrepresented in the existing literature.

Herb consumption is on the rise in Iran, especially among patients with chronic diseases. Cancer management has become a primary focus of public health policies, claiming considerable healthcare resources. Despite advancements in conventional medical treatments, they often fail to fully address patients' needs. As a result, there has been a growing trend among cancer patients toward using medicinal plants (22). These are available either as unprocessed herbs (sold in traditional perfumeries) or as formulated herbal medicines (distributed in pharmacies). The use of CAM, including herbal remedies, varies significantly across cultures and regions due to differing perspectives and practices. Physicians' approaches to CAM also range widely, from active encouragement to skepticism or outright criticism (23).

Our study found that the most frequently used herbs during the early stages of cancer included mint, musk willow, and licorice. The selection of medicinal plants often depends on local beliefs, geographic conditions, and the prevalence of particular diseases in a given area. For instance, a study by Ashayeri et al. (24) explored the commonly purchased medicinal plants from perfumeries in Tehran, Iran. The findings uncovered seasonal variations: In spring, the most bought plants were Viper's-buglosses, valerian, Descurainia sophia, and violet; in summer, D. sophia, chicory, common fumitory, and chia; in autumn, thyme, mallow, hollyhocks, and violet; and in winter, cinnamon, ginger, "four flowers", and thyme.

Similarly, Paryab and Raeeszadeh (25) evaluated the usage patterns and motivations behind medicinal plant consumption among patients visiting specialized medical centers in Fars province. The study revealed that skin diseases accounted for the highest use of medicinal plants (30%), followed by respiratory ailments (21.5%), urinary conditions (20%), endocrine issues (18.5%), and gastrointestinal disorders (10%). Popular herbs included licorice, thyme, musk willow, and "four seeds". Differences in the types of herbs consumed can be attributed to varying cultural practices, socioeconomic factors, environmental diversity, regional vegetation, and the availability of medicinal plants.

Another study by Ameri (26) investigated the forms in which herbal remedies were consumed. Their findings showed that 41.8% of medicinal plants were brewed into teas or infusions, while 29.8% were consumed raw (directly used as food or for external applications), 24.5% were utilized as herbal liqueurs, and 3.9% were prepared in other ways (e.g., smoking, soaking, or extracting plant leachates). Additionally, they explored spiritual practices among cancer patients, revealing that many relied on prayers, vows, and sacrificial rituals as complementary healing methods.

Similarly, Sajadian et al. (27) studied 625 cancer patients and found that 219 of them had turned to a minimum of one CAM approach. Among these, prayer was the most common method, used by 179 respondents. The remaining participants utilized other methods such as energy therapy (20 individuals), homeopathy (26 individuals), and herbal medicine or phytotherapy (7 individuals). Furthermore, Sedighi et al. (23) researched 4,123 individuals, concluding that 83.2% had adopted at least one CAM practice. In this study, the breakdown of CAM usage was as follows: Herbal medicine (38.4%), energy therapy (3.4%), yoga (3%), acupuncture (2.7%), meditation (1.3%), hypnosis (1.2%), and homeopathy (0.4%). Notably, a study conducted by Jermini et al. (5) revealed that commonly used CAM modalities included herbal medicines (35%), dietary supplements (27%), and homeopathy (27%).

These findings align with broader international evidence. For example, a study on CAM use among patients with chronic viral hepatitis in Somalia revealed widespread reliance on culturally-informed therapies, underscoring the global and cross-disease relevance of CAM as a patient-driven phenomenon. This reinforces the need for clinician awareness and open communication about CAM across diverse medical contexts (28). In Iran, CAM usage is not limited to oncology. A cross-sectional study conducted at a Shiraz diabetes clinic found that CAM use was highly prevalent among patients with diabetic foot ulcers. This supports the argument that CAM is a systemic health behavior in Iran, warranting routine clinical screening and integration into broader healthcare strategies (29). Moreover, ethical considerations in CAM research are critical. A recent investigation into clinical trials involving herbal and complementary medicines revealed that 24% of studies failed to mention informed consent. This gap highlights the need for ethical oversight and documentation, especially in oncology care where patients may be vulnerable and seeking alternative therapies (30).

The variation in spiritual or mental healing methods across populations is largely shaped by cultural and social factors. These differences likely account for the varying findings across studies on CAM usage among cancer patients. Understanding these diverse approaches is essential in designing culturally sensitive healthcare strategies that accommodate different patient needs and preferences. Although this study did not directly assess clinical outcomes such as symptom relief or quality-of-life metrics, patients’ perceptions of benefit were substantial. The majority of patients (78.5%) indicated that their primary motivation for using complementary medicine was exploring any option that might assist in treating their illness. Another commonly cited reason was their belief in the minimal side effects associated with complementary medicine.

Similarly, in the study conducted by Sajadian et al. (27), the main motivations for patients seeking CAM included its perceived safety, its potential to enhance physical well-being, and the possibility of extending life expectancy. Other studies have pointed out that patients often turn to CAM for benefits such as psychosomatic improvements, immune system strengthening, faster recovery, and reduced complications from illnesses (31-33). Research also suggests that cancer patients frequently pursue complementary treatments to enhance their quality of life and alleviate stress or fears of cancer recurrence (7, 11, 34). In less developed countries, economic constraints prevent some patients from accessing conventional medical services. Thus, the affordability and availability of complementary medicine make it a more attractive solution in these areas (35-37). However, more randomized controlled trials are needed to establish scientific evidence for CAM efficacy in cancer care. Future studies should employ validated tools to quantify these outcomes and further clarify the therapeutic value of CAM in oncology care.

Notably, 91.5% of the patients in our study did not inform their physicians about using CAM alongside conventional medicine. There are several reasons for this lack of transparency. Many patients believe their queries and concerns are not taken seriously by physicians. Additionally, some perceive that physicians lack adequate knowledge about CAM, leading to opposition to its use. Most physicians argue that there is insufficient scientific evidence to substantiate CAM's effectiveness. They also believe that promoting CAM could foster false hopes among patients and potentially discourage them from pursuing scientifically validated treatments, which could ultimately harm their health. This skepticism from physicians discourages patients from discussing their use of CAM.

To address this issue, there is a pressing need to improve physician-patient communication and provide physicians with proper training in complementary medicine. With meticulous planning and education efforts, the use of effective and informed complementary medicine practices could become more prevalent in Iran in the future. The study also revealed that most patients learned about various types of CAM through informal networks such as friends, acquaintances, and media outlets before incorporating them into their treatment plans. A significant number of participants purchased herbal medicines or plants from local markets (e.g., perfumeries) and pharmacies. Across studies, perfumeries and pharmacies consistently emerge as the primary sources of complementary medicine. For instance, Paryab and Raeeszadeh (25) reported that in Fars province, 70% of medicinal plant purchases were made through perfumeries. Such findings suggest a high level of trust among people toward perfumeries as suppliers of medicinal plants.

Jones et al. (6) proposed that additional research is essential to deepen our understanding of the factors impacting cancer patients' utilization of CAM. Furthermore, they emphasized the significance of exploring how healthcare professionals can effectively support patients in this domain, given that the use of CAM is a multifaceted issue shaped by numerous influencing variables. This highlights an essential need to ensure that perfumeries are adequately educated about medicinal plants through systematic training programs. Moreover, regular oversight by the Ministry of Health is necessary to regulate the preparation and distribution processes in these establishments.

Another aspect of our study focused on potential drug-herb interactions that may have occurred during data collection. As the use of CAM continues to rise, particularly among patients with critical illnesses such as cancer, the likelihood of herb-drug interactions within oncology increases significantly. However, the precise mechanisms underlying these interactions — such as how CAM may induce metabolizing enzymes or drug transporters — remain largely unclear. These potential interactions could diminish the therapeutic effects of conventional treatments by inducing metabolic enzymes and drug transporters. Therefore, it is crucial for treating physicians to recognize the risks associated with these interactions.

While many patients report satisfaction with CAM and would recommend it to others (4), another study identified concerns regarding potential interactions between herbal remedies and conventional drugs, highlighting the necessity for improved communication between patients and oncologists (5). Our study underscores several likely drug-herb interactions commonly observed in cancer patients to draw the attention of healthcare professionals to these potential risks and ensure better patient safety in oncology care.

Younger patients and those with lower levels of formal education were significantly more likely to engage in CAM, particularly herbal remedies and ritual-based practices. These findings align with global trends, where younger and less formally educated patients often report higher CAM engagement, particularly for symptom relief and spiritual support (38, 39). For instance, a multicenter study in Germany (39) found that CAM users were typically younger and more distressed, with longer disease duration and more advanced cancer stages — paralleling our observation that metastatic disease and extended treatment duration strongly predicted CAM use.

Interestingly, while mental methods such as prayer and spiritual healing were commonly used, their association with metastatic disease reversed after adjustment, suggesting that patients in earlier stages may turn to these practices for emotional coping. This nuance reflects broader cultural and psychological dimensions of CAM use, as highlighted in a study from Saudi Arabia (35), which noted shifting CAM motivations over time — from cancer treatment to symptom management and spiritual well-being. The strong association between metastatic disease and alternative medicine (e.g., homeopathy) use may reflect a search for hope or control in the face of limited conventional options. However, the inverse relationship between education and CAM use — particularly for herbs and alternative therapies — suggests that awareness of evidence-based medicine may temper reliance on unproven modalities. These patterns emphasize the importance of culturally sensitive, individualized communication in oncology settings, where understanding patients’ beliefs and motivations can guide safer, more integrated care strategies.

While this study has provided valuable insights, it is essential to reflect on the challenges faced and their potential impact on the results. Research on CAM faces numerous methodological and conceptual challenges. A notable limitation of the present study is that, although scientific inquiry provides essential tools for evaluating CAM, prevailing scientific paradigms and researcher biases may inadvertently hinder objective and meaningful assessment. Most of the initial clinical trials on CAM have serious methodological flaws such as low statistical power, including poor controls and no comparisons. In this study, we faced more constraints than other studies due to variations in treatments and non-standardized herbal medicines.

The results underscore the importance of oncologists and pharmacists actively asking patients about CAM, particularly herbal medicine, during routine visits. Because of the risk of significant drug-herb interactions when using these CAM modalities, the inclusion of CAM education in cancer care is important. Finally, regulation of vendors of herbal products and public education campaigns may reduce risks and at the same time encourage informed decision-making by cancer patients.

5.1. Conclusions

This study underscores the widespread and multifaceted use of CAM among cancer patients in Iran, revealing a complex interplay between clinical status, sociodemographic factors, and personal beliefs. Despite the high prevalence of CAM — particularly herbal remedies and ritual-based practices — most patients do not disclose their usage to healthcare providers, raising significant concerns about potential drug-herb interactions and compromised treatment safety. The identification of key predictors such as younger age, male gender, lower education, metastatic disease, and longer treatment duration provides valuable insight into patient behavior and decision-making.

These findings highlight the urgent need for improved communication between oncology teams and patients regarding CAM use. Routine screening for herbal and alternative therapies should be integrated into clinical practice to ensure safe, coordinated care. Moreover, culturally sensitive education and engagement strategies are essential to bridge the gap between conventional medicine and CAM, fostering trust and informed decision-making. Future research should explore interventions that promote transparency and evaluate the clinical impact of CAM integration in cancer care.