1. Background

Peptic ulcer (PU) is a common and multifactorial gastrointestinal disorder with significant global prevalence and the potential for serious complications such as bleeding and perforation. It results from an imbalance between aggressive factors (e.g., acid, pepsin, NSAIDs, ethanol, Helicobacter pylori) and the protective mechanisms of the gastric mucosa (e.g., mucus, bicarbonate, prostaglandins, antioxidant enzymes) (1-4). Despite the availability of standard treatments like proton pump inhibitors and antibiotics, challenges such as drug resistance, side effects, and frequent recurrence persist, emphasizing the need for alternative, more effective therapies (5, 6).

In recent years, interest has grown in plant-based remedies due to their multifaceted therapeutic properties and lower toxicity. Among these, Pistacia atlantica Desf. subsp. mutica, a native medicinal plant of Iran, has been traditionally used for alleviating gastrointestinal disorders, particularly gastric ulcers. The oleoresin extracted from the tree’s trunk contains bioactive constituents such as α-pinene, flavonoids, and phenolic compounds, which exhibit antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, antimicrobial, and gastroprotective effects (6-8). Previous studies have demonstrated its ability to protect the gastric mucosa against ethanol-induced injury and inhibit the growth of H. pylori, supporting its potential as an ulcer-preventive agent (6).

However, like many herbal extracts, P. atlantica oleoresin suffers from certain pharmacological limitations, including poor aqueous solubility, low bioavailability, and degradation in acidic environments. These factors can reduce its clinical effectiveness and limit its gastroprotective application (9, 10).

To overcome these limitations, nanoparticle-based drug delivery systems have gained considerable attention. Polymeric nanoparticles can encapsulate unstable phytochemicals, enhance their chemical stability, improve gastric retention, and promote localized delivery to ulcerated tissues (11-15). Furthermore, these carriers protect active compounds from enzymatic and acidic degradation, facilitate better mucosal adhesion, and increase cellular uptake, thereby amplifying their protective efficacy (16-18).

In the context of ulcer management, these properties are particularly advantageous. Nanoparticles may act as both carriers and gastroprotective agents, creating a physical barrier over the ulcer site while delivering phytochemicals directly to damaged tissue. This dual function offers a promising strategy to enhance the healing rate, reduce inflammation, and minimize oxidative stress in the ulcerated gastric mucosa (19-21).

Therefore, the combination of P. atlantica oleoresin with nanocarrier systems is expected to produce a synergistic effect, improving both the bioavailability and gastroprotective activity of the plant extract.

2. Objectives

This study was conducted to develop and optimize a nanoparticulate formulation of P. atlantica oleoresin and evaluate its protective effects in the form of P. atlantica oleoresin nanoparticles (PAONPs) in an ethanol-induced gastric ulcer model in rats.

3. Methods

3.1. Plant Material

The oleoresin of P. atlantica was harvested from the Kermanshah province in western Iran. It was collected by making shallow incisions on the trunks and branches of mature trees, allowing the resinous exudate to naturally ooze and solidify over several days. After collection, the oleoresin was stored at room temperature in clean, amber-colored glass containers. Prior to use, the resin was passed through a fine mesh filter to remove any dust or physical impurities. No further chemical purification or extraction was applied.

The plant material was authenticated from the Department of Pharmacognosy, Faculty of Pharmacy, Tehran University of Medical Sciences. A voucher specimen (No. PMP-818) is preserved in the Herbarium of the Faculty of Pharmacy. (22).

3.2. Preparation of Nanoparticles

The experimental design software was used to determine the appropriate variables, which included the solvent, oleoresin concentration, and aqueous/organic volume ratio. The PAONPs were synthesized using two solvents: Absolute ethanol and acetone. The oleoresin concentration ranged from 2 to 5% (w/v), and the aqueous/organic volume ratio varied from 1/5 to 1/15. These were input variables for the Design Expert software, which arranged 26 experimental setups. Nanoprecipitation was employed for PAONP synthesis (23). Pistacia atlantica oleoresin was dissolved in ethanol and acetone at concentrations of 2, 3.5, and 5% (w/v), stirred for 30 minutes at room temperature, and slowly introduced into the aqueous phase under rapid stirring to achieve aqueous/organic volume ratios of 1/5, 1/10, and 1/15. The solution was centrifuged at 15,000 RPM for 20 minutes, leading to PAONP precipitation, which was washed and dispersed in distilled water and processed with an ultrasonic bath for 11 minutes. This PAONP suspension was then used for subsequent analyses.

3.3. Characterization of Nanoparticles of Pistacia atlanticaitalic>

3.3.1. Zetasizer Analyzer

The fabricated PAONPs’ average size, distribution, and zeta potential were measured with the Zetasizer Nano ZS (Malvern, UK) in water at ambient temperature.

3.3.2. Transmission Electron Microscopy

The morphology of the synthesized PAONPs was examined under optimal conditions using a Philips CM120 transmission electron microscope.

3.3.3. Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy

Fourier-transform infrared (FT-IR) spectroscopy (IRPrestige-21, Shimadzu, Japan) was used to identify and analyze the functional groups of the synthesized PAONPs.

3.4. Experimental Animals

Experiments were conducted on mature female albino Wistar rats (190 - 230 g), maintained under standard laboratory conditions with a 12-hour light/dark cycle and a temperature of 23 ± 2°C, with free access to food and water, in accordance with established guidelines for laboratory animal care (24). Rats were fasted for 24 hours before the experiments, as previously described (6). All procedures adhered to ethical guidelines and were approved by the Institutional Ethics Committee of Kermanshah University of Medical Sciences [ethics code: (IR.KUMS.REC.1396.719)].

3.5. Ethanol-Induced Gastric Ulcers

Forty female Wistar rats were randomly divided into nine groups (n = 5 per group) as follows (Table 1):

• Group 1 [normal control (NC)]: Received distilled water (1 mL orally), no ulcer induction.

• Group 2 [ulcer control (UC)]: Received distilled water (1 mL orally), followed by ethanol-induced ulcer.

• Group 3 [omeprazole (OMP)]: Received OMP (10 mg/kg body weight) orally before ethanol administration.

• Group 4 [oleoresin 50 (OL50)]: Received P. atlantica oleoresin at 50 mg/kg orally.

• Group 5 [oleoresin 100 (OL100)]: Received P. atlantica oleoresin at 100 mg/kg orally.

• Group 6 [oleoresin 200 (OL200)]: Received P. atlantica oleoresin at 200 mg/kg orally.

• Group 7 [PAONPs 50 (NP50)]: Received PAONPs at 50 mg/kg orally.

• Group 8 [PAONPs 100 (NP100)]: Received PAONPs at 100 mg/kg orally.

• Group 9 [PAONPs 200 (NP200)]: Received PAONPs at 200 mg/kg orally.

One hour after treatment administration, all groups except the NC (group 1) were given 80% ethanol (1 mL/200 g body weight) via oral gavage to induce gastric ulcers (25). One-hour post-ethanol administration, animals were euthanized, and their stomachs were excised for macroscopic and microscopic evaluations.

| Groups | Group Name | Abbreviation | Treatment Administered | Ulcer Induction a |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Normal control | NC | Distilled water (1 mL orally) | No ethanol |

| 2 | Ulcer control | UC | Distilled water (1 mL orally) | 80% ethanol |

| 3 | Omeprazole (reference) | OMP | Omeprazole 10 mg/kg orally | 80% ethanol |

| 4 | Oleoresin 50 mg/kg | OL50 | Pistacia atlantica oleoresin, 50 mg/kg orally | 80% ethanol |

| 5 | Oleoresin 100 mg/kg | OL100 | P. atlantica oleoresin, 100 mg/kg orally | 80% ethanol |

| 6 | Oleoresin 200 mg/kg | OL200 | P. atlantica oleoresin, 200 mg/kg orally | 80% ethanol |

| 7 | PAONPs 50 mg/kg | NP50 | PAONPs, 50 mg/kg orally | 80% ethanol |

| 8 | PAONPs 100 mg/kg | NP100 | PAONPs, 100 mg/kg orally | 80% ethanol |

| 9 | PAONPs 200 mg/kg | NP200 | PAONPs, 200 mg/kg orally | 80% ethanol |

Abbreviation: PAONPs, Pistacia atlantica oleoresin nanoparticles.

a 1 mL/200 g

3.6. Measurement of Ulcer Index

Gastric ulcers were assessed under a dissecting microscope, with lesions graded as follows (6): Score 1 (every fifth petechia as 1 mm), Score 2 (lesion 1 - 2 mm), Score 3 (lesion 2 - 4 mm), Score 4 (lesion 4 - 6 mm), and Score 5 (lesion > 6 mm). The Ulcer Index was calculated using the formula:

Ulcer Index = 1 × (Score 1) + 2 × (Score 2) + 3 × (Score 3) + 4 × (Score 4) + 5 × (Score 5) (1)

The protection rate (%) was determined using:

Protection rate (%) = [(UC Ulcer Index - Test group Ulcer Index) / (UC Ulcer Index)] × 100 (2)

Where UC refers to the UC group, and the test groups include OMP, OL50 - OL200, and NP50 - NP200, representing OMP, oleoresin, and PAONPs at various doses, respectively.

3.7. Microscopic Evaluation of Gastric Ulcer

For microscopic evaluation, gastric segments fixed in 10% formalin were embedded in paraffin and sectioned at 5 μm using an automated microtome. Sections were stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E), and histopathological changes were assessed by individuals blinded to group assignments (6). Evaluation focused on mucosal integrity, presence of erosion, necrosis, inflammation, and structural preservation, comparing results across all experimental groups, including NC, UC, OMP, OL50 OL200, and NP50 - NP200.

3.8. Statistical Analysis

Data analysis was conducted using Design Expert software (Version 8.0.7.1, Stat-Ease, Inc., USA), and differences between groups were evaluated using one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s post-hoc test, using GraphPad Instat 3 Software (GraphPad Instat 3 Software, Inc., USA). Results are reported as mean ± SD, with P < 0.05 considered statistically significant (26).

4. Results

4.1. Particle Size and Nanoparticle Dispersion Index Assay

The pre-designed tests were meticulously conducted to record the PAONPs' size and corresponding nanoparticle Polydispersity Index (nPDI) values. As detailed in Table 2, the sizes of the PAONPs varied from 155.1 to 288.4 nm, while the nPDI values ranged between 0.064 and 0.315. The resulting PAONPs exhibited homogeneity and uniformity in both size and distribution. Such uniformity is crucial for drug delivery applications (13, 27), suggesting that the synthesized PAONPs possess optimal characteristics for pharmaceutical purposes.

| Run | A a | B b | C c | Size (nm) | nPDI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 3.5 | 10 | Ethanol | 243.3 | 0.201 |

| 2 | 5 | 15 | Acetone | 193 | 0.239 |

| 3 | 3.5 | 10 | Ethanol | 240.5 | 0.211 |

| 4 | 5 | 5 | Acetone | 185.2 | 0.222 |

| 5 | 2 | 15 | Ethanol | 155.1 | 0.121 |

| 6 | 2 | 15 | Acetone | 247.2 | 0.194 |

| 7 | 3.5 | 15 | Ethanol | 210.8 | 0.064 |

| 8 | 3.5 | 15 | Acetone | 221.8 | 0.091 |

| 9 | 3.5 | 10 | Acetone | 222.2 | 0.145 |

| 10 | 2 | 10 | Ethanol | 183.4 | 0.218 |

| 11 | 3.5 | 5 | Ethanol | 191.5 | 0.220 |

| 12 | 3.5 | 10 | Acetone | 242.6 | 0.228 |

| 13 | 3.5 | 10 | Ethanol | 173.2 | 0.111 |

| 14 | 5 | 10 | Acetone | 288.4 | 0.315 |

| 15 | 2 | 5 | Ethanol | 200 | 0.202 |

| 16 | 3.5 | 10 | Acetone | 221.2 | 0.150 |

| 17 | 5 | 10 | Ethanol | 179.9 | 0.254 |

| 18 | 3.5 | 10 | Acetone | 240 | 0.220 |

| 19 | 3.5 | 10 | Acetone | 242 | 0.226 |

| 20 | 3.5 | 5 | Acetone | 239.8 | 0.225 |

| 21 | 2 | 10 | Acetone | 267.9 | 0.192 |

| 22 | 5 | 15 | Ethanol | 167 | 0.149 |

| 23 | 3.5 | 10 | Ethanol | 242 | 0.215 |

| 24 | 2 | 5 | Acetone | 211.2 | 0.160 |

| 25 | 5 | 5 | Ethanol | 205.8 | 0.278 |

| 26 | 3.5 | 10 | Ethanol | 251 | 0.220 |

Abbreviation: nPDI, nanoparticle Polydispersity Index.

a Concentration of Pistacia atlantica oleoresin (v/w).

b Aqueous/organic volume ratio.

c Solvent type.

Upon introducing the response variables — namely, PAONP size and nPDI — into the Design Expert software, we assessed the correlation between these responses and the experimental variables by fitting the data to a quadratic equation. The specific equations for PAONP size and nPDI are presented below:

Size (ethanol) = +191.88 - 12.68A + 7.93B - 1.34AB + 3.50A2 - 0.468B2 (3)

Size (acetone) = +207.97 - 2.84A - 11.96B - 1.34AB + 3.50A2 - 0.468B2 (4)

The nPDI (ethanol) = +0.46212 - 0.22384A + 0.014836B - 0.001583AB + 0.037096A2 - 0.000991B2 (5)

The nPDI (acetone) = +0.35596 - 0.21495A + 0.025803B - 0.001583AB + 0.037096A2 - 0.000991B2 (6)

Where A represents the concentration of P. atlantica oleoresin in the organic phase, and B denotes the aqueous/organic volume ratio.

These equations demonstrate that not only do individual variables have significant effects, but interactions between pairs of variables also play a critical role in influencing both PAONP size and nPDI. The statistical significance of the modeled equations was further validated through analysis of variance, indicating that the quadratic regression model is statistically robust, with a confidence level of 95% and P < 0.0001 (detailed results are available in Appendix 1 of the Supplementary Material).

The model’s efficacy is quantified by the coefficient of determination (R2), with values of 0.9932, 0.9900, and 0.9827 for PAONP size, and 0.9533, 0.9314, and 0.8729 for nPDI, respectively. The P-values from the lack-of-fit test were 0.5543 for PAONP size and 0.1354 for nPDI, indicating no significant difference between the lack of fit and pure error. This suggests that the model holds considerable merit.

Table 2 further outlines that variables A, B, and C, as well as interaction terms AC, BC, AB, and quadratic terms B2 and A2, are critical for accurately modeling PAONP size and nPDI. The insignificant lack of fit indicates that the model is appropriate for the data.

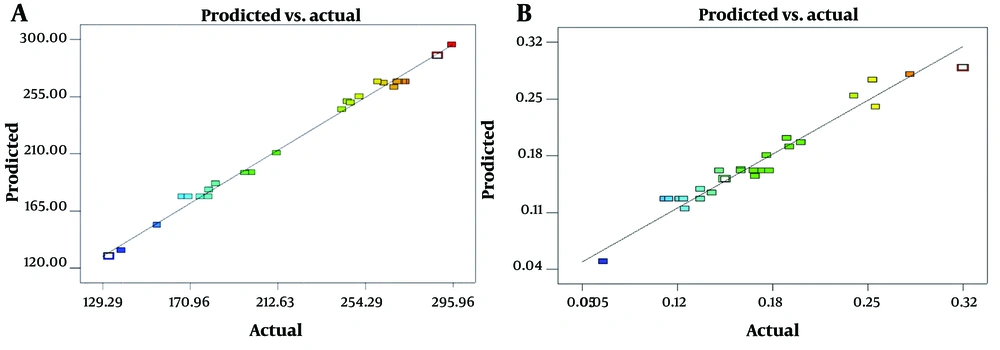

Figure 1 presents plots comparing predicted versus actual values for both PAONP size and nPDI, illustrating a strong alignment with a 45° diagonal line. This alignment validates the estimates produced by the Response Surface Methodology (RSM) Model, confirming its capability to accurately fit the data.

4.2. Optimization and Validation of the Proposed Model

Optimization was conducted following the correlation of PAONP size and nPDI with experimental variables, ensuring the model’s accuracy and validity. Initially, optimization criteria were established within the software, focusing on achieving the smallest possible PAONP size and the lowest nPDI. The results summarized in Table 3 highlight that the optimal conditions for these parameters were achieved with a concentration of P. atlantica oleoresin at 3.18% (w/v), an aqueous/organic volume ratio of 1/14.85, and ethanol as the solvent. Under these conditions, the resultant PAONP size was measured at 141.5 nm, and the nPDI reached 0.069.

Abbreviations: nPDI, nanoparticle Polydispersity Index; PAONP, Pistacia atlantica oleoresin nanoparticle.

a Predicted PAONP size (nm).

b Predicted PAONP nPDI.

c Concentration of P. atlantica oleoresin (% w/v).

d Aqueous/organic phase ratio.

e Solvent type.

To further confirm the model’s predictive accuracy, PAONPs were synthesized under optimal conditions through three repeated experiments. The average PAONP size and nPDI observed were 173.63 ± 8.83 nm and 0.066 ± 0.018, respectively. A comparison between the experimentally obtained values and those predicted by the model indicates the model’s validity in optimizing the variables necessary for generating desirable PAONPs. Statistical analysis showed no significant difference between the experimentally determined optimal values and the predicted values from the model, with a P-value of less than 0.05.

After the optimization and validation process, the yield of PAONP fabrication was calculated by dividing the number of PAONPs produced by the initial amount of oleoresin used in the fabrication. Under optimal conditions, the yield was determined to be 64%, demonstrating an efficient fabrication process.

4.3. Characterization of Pistacia atlantica Oleoresin Nanoparticles

The size distribution of the PAONPs fabricated under optimal conditions is depicted in Figure 2. The findings confirm that the PAONPs exhibit uniform size, validating the proposed model’s optimization and ensuring its accuracy.

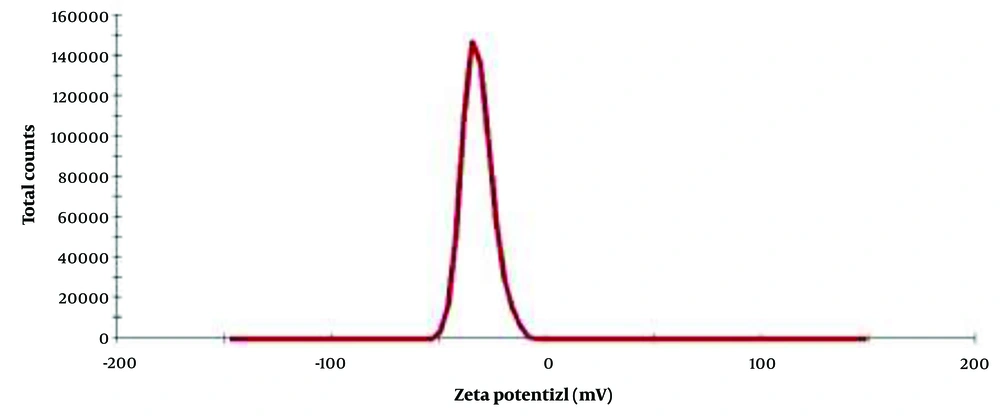

The Zeta potential analysis, shown in Figure 3, indicates that the optimal PAONPs possess a Zeta potential of -31.9 mV. This negative charge is attributed to the OH groups of terpenoids present on the particle surfaces. Zeta potential is a crucial factor affecting the stability of drugs in the bloodstream. Studies (28, 29) suggest that positively charged nanoparticles are more likely to interact with circulating proteins or be cleared by the reticuloendothelial system. The negative charge of these PAONPs suggests they are likely to remain stable within the circulatory system.

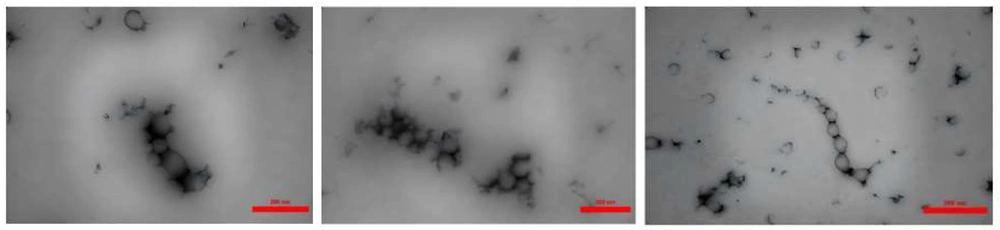

Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) analysis, illustrated in Figure 4, reveals that the PAONPs are predominantly spherical and exhibit an acceptable size distribution. While some variations in electron transparency were observed, which are characteristic of plant-based nanoparticles, no definitive internal structure can be concluded from the current images. The average particle size was estimated to be 107.573 nm.

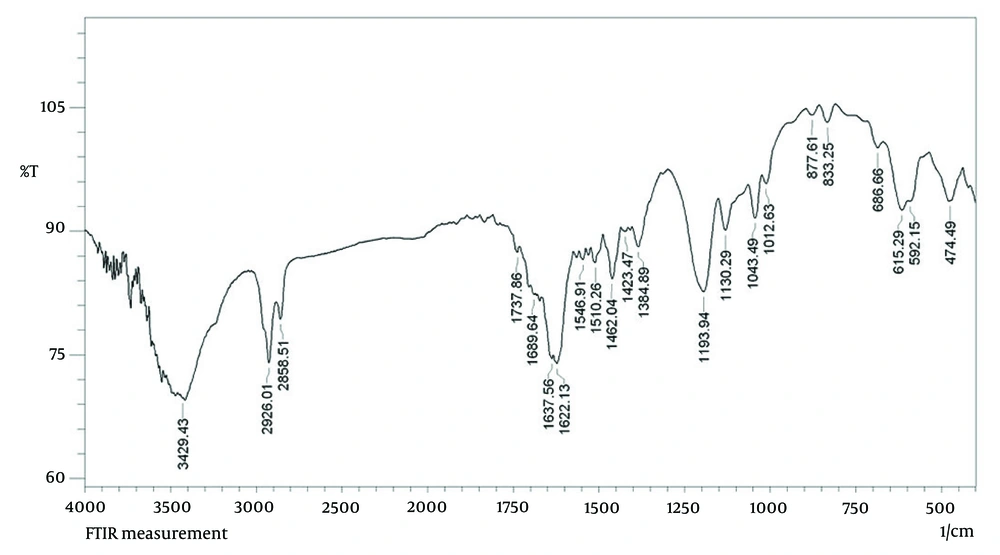

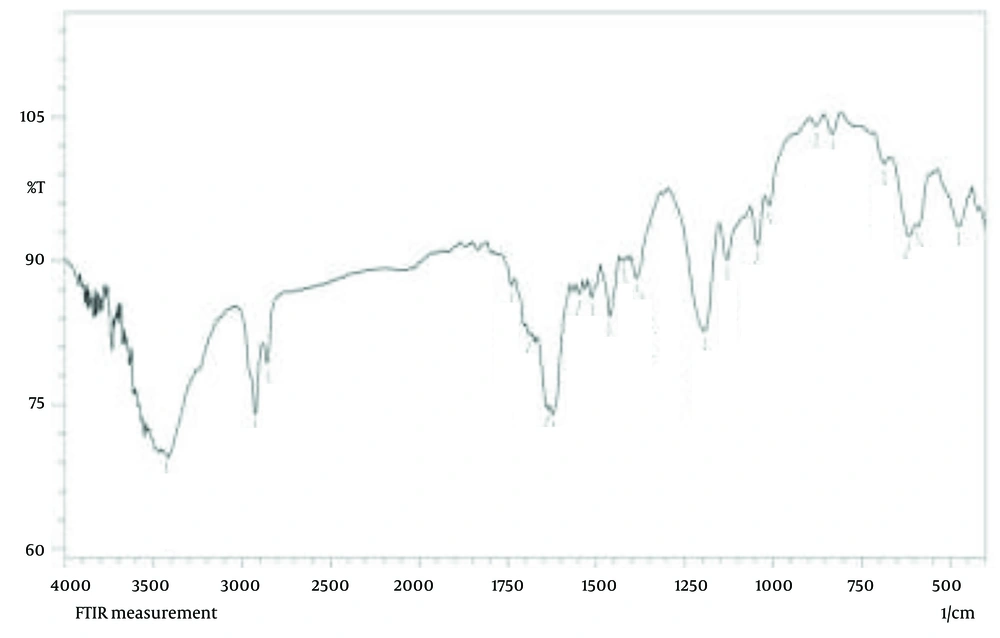

The FT-IR was used to analyze the functional groups of the biomolecules present in the PAONPs (Figure 5). The FT-IR spectrum identified characteristic infrared bands associated with phenolic compounds at 3429, 1737, 1622, 1384, 1193, 1043, 686, and 474 cm-1, corresponding to the -OH stretching vibration, C=O stretching, O=C–O⁻ asymmetric stretching, O=C–O⁻ symmetric stretching, C–O stretching, C–O–C bending, O–C=O bending, and C–C=O bending of phenolic compounds (31). Additional peaks for the oleoresin extract were observed at 2926 cm-1 (C–H stretching), 2858 cm-1 (N–H stretching vibration of amide II), 1510 cm-1 (amide II), 1462 cm-1 (amine I bands), 1130 cm-1 (C–N of amines), 833 cm-1 (N–H out-of-plane bending), and 615 cm-1 (N–C=O bending) (30, 31). These peaks confirm the presence and integrity of terpenoid functional groups within the PAONPs.

4.4. Gastroprotective Activity of Pistacia atlantica Oleoresin Nanoparticles

4.4.1. Macroscopic Evaluation

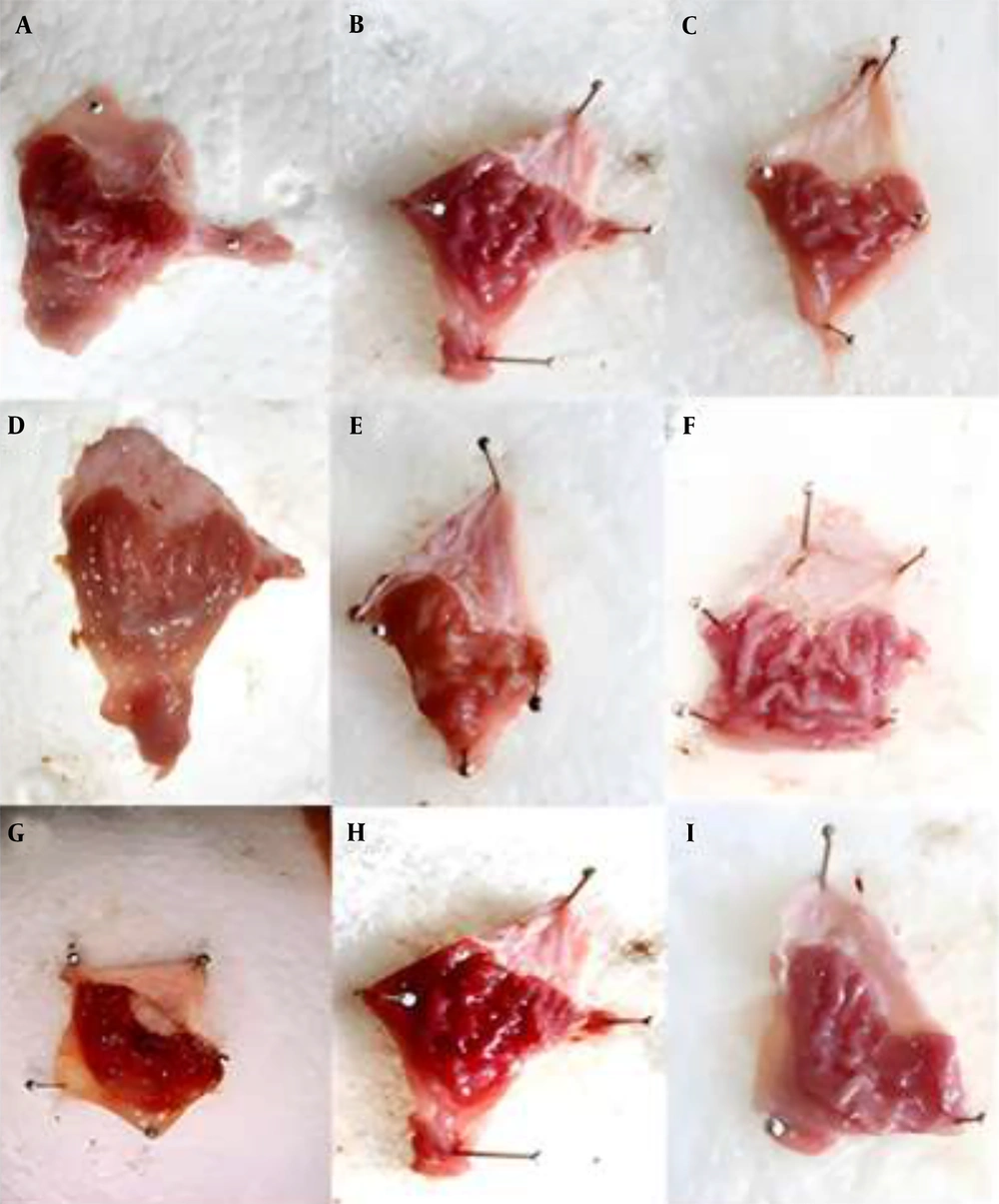

Figure 6 displays the stomach photographs of different rat groups following ethanol administration. For macroscopic assessment, we examined the impact of orally administered ethanol, which induced longitudinal gastric ulcers in the glandular region of the stomach, as shown in Figure 7.

Representative photographs of the gastric mucosa from each experimental group: A-C, PAONPs 50, 100, and 200 mg/kg (NP50, NP100, and NP200), respectively; D-F, oleoresin 50, 100, and 200 mg/kg (OL50, OL100, and OL200), respectively; G, ulcer control (UC); H, omeprazole (OMP)-treated group; I, normal control (NC).

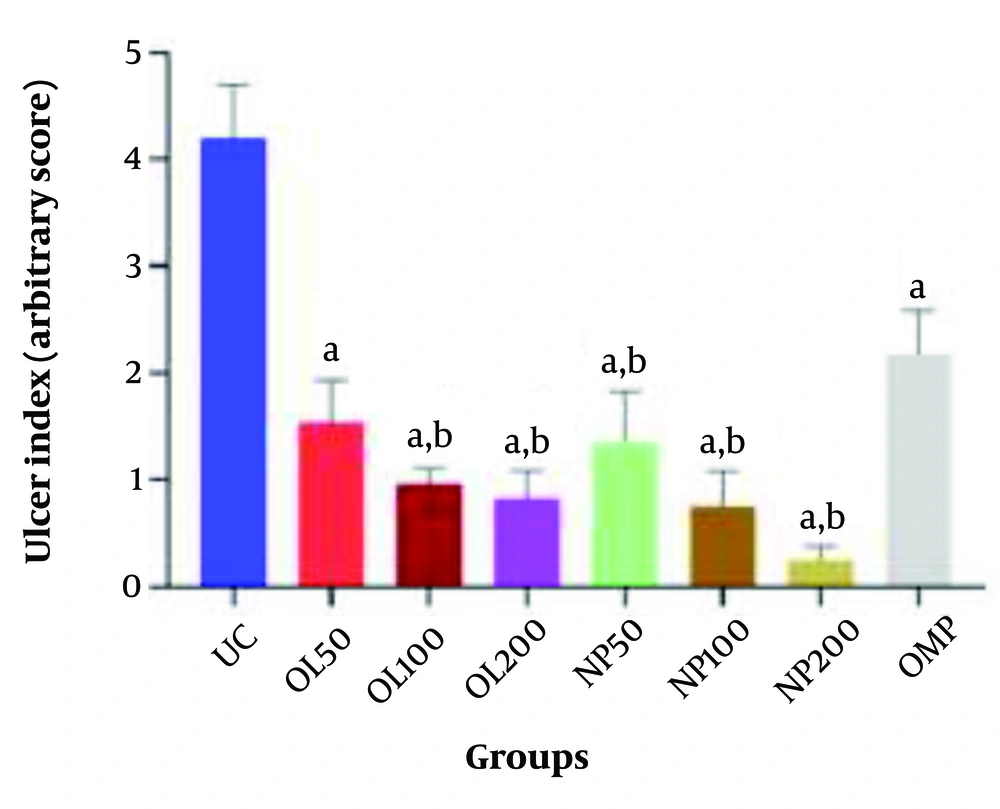

Comparison of Ulcer Index among experimental groups. Values are presented as mean ± SEM (n = 5). Groups: Oleoresin 50 (OL50), oleoresin 100 (OL100), oleoresin 200 (OL200) = Pistacia atlantica oleoresin nanoparticles (PAONPs) at 50, 100, and 200 mg/kg; NP50, NP100, NP200 = PAONPs at 50, 100, and 200 mg/kg; omeprazole (OMP) = 10 mg/kg; ulcer control (UC) = ethanol-induced ulcer, untreated. Statistical analysis: One-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s test. Symbols: (a) P < 0.05 vs. UC group; (b) P < 0.05 vs. OMP group.

The UC group exhibited the highest Ulcer Index at 4.69 cm. In comparison, the oral administration of varying doses of PAONPs (NP50, NP100, and NP200) resulted in a significant reduction of ethanol-induced gastric ulcers in a dose-dependent manner. All PAONP-treated groups demonstrated a markedly lower Ulcer Index than the UC group (P < 0.05) (Figure 7).

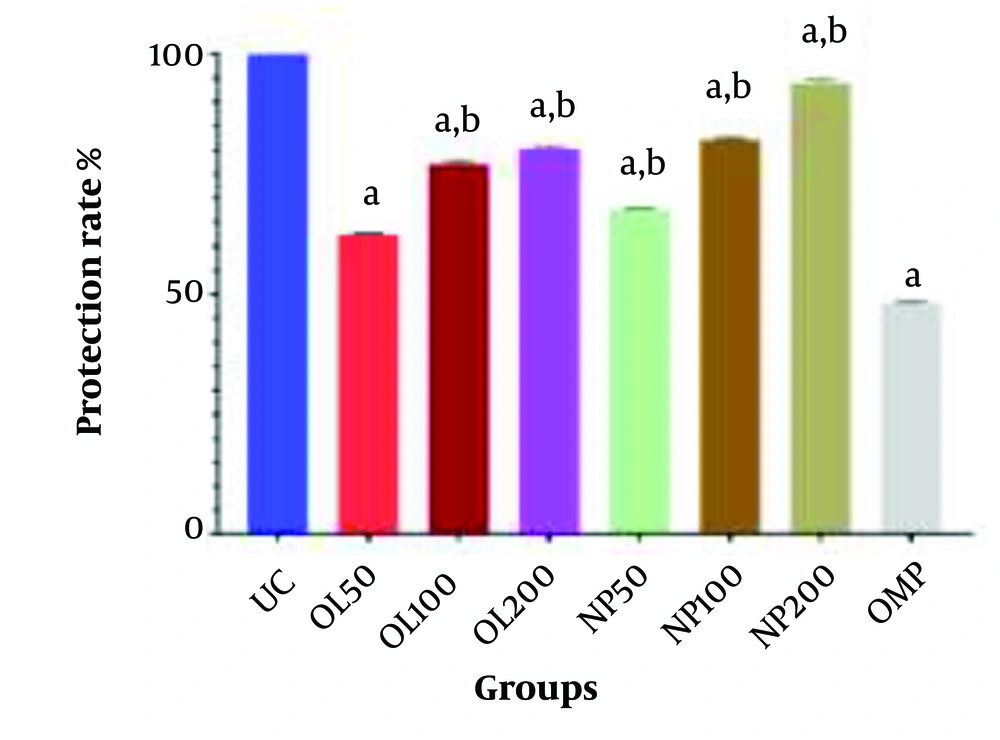

Notably, the group receiving NP200 exhibited the lowest Ulcer Index compared to other experimental groups, which was significantly lower than that of the standard drug group, OMP (P < 0.05). Moreover, groups treated with PAONPs showed superior gastroprotective effects compared to those treated with the oleoresin alone (OL50 - OL200). Additionally, the highest dose of PAONPs (NP200) demonstrated a significantly greater protective effect against PUs than the OMP group (P < 0.05) (Figures 7 and 8).

Protection rate (%) against ethanol-induced gastric ulcer in different treatment groups. Values are presented as mean ± SEM (n = 5). Group definitions as in Figure 7. Statistical analysis: One-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s test. Symbols: (a) P < 0.05 vs. ulcer control (UC) group; (b) P < 0.05 vs. omeprazole (OMP) group.

4.4.2. Microscopic Evaluation

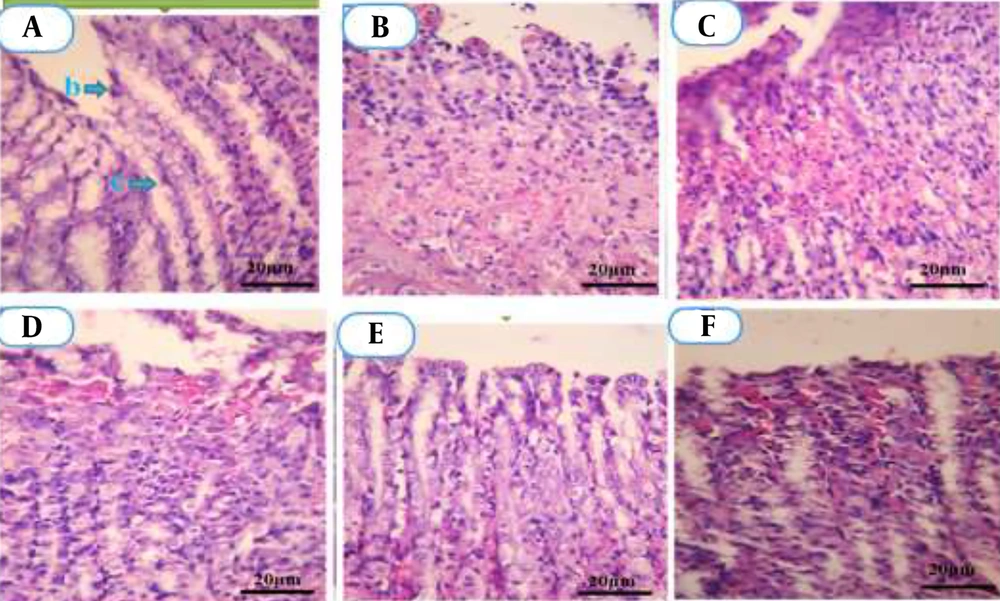

Histopathological analysis of gastric tissue is illustrated in Figure 9. The NC group (A) exhibited typical tubular gland structures. In contrast, microscopic evaluation of gastric lesions induced by ethanol in the UC group (B) revealed atypical tubular glands. Severe damage was noted, including extensive bleeding, diffuse necrosis, infiltration of leukocytes and red blood cells, erosions, destruction of epithelial and glandular tissues, as well as cellular irregularity.

Microscopic images of gastric tissue sections stained with Hematoxylin and Eosin (H&E), magnification ×400. A, Normal control (NC): Shows intact gastric mucosa with preserved epithelial layer (b) and typical mucosal glands (c); B, Ulcer control (UC): Displays severe mucosal damage, necrosis, and inflammatory cell infiltration; C - E, Pistacia atlantica oleoresin nanoparticles (PAONPs)-treated groups at 50, 100, and 200 mg/kg (NP50, NP100, NP200): Gradual mucosal regeneration, with NP200 showing nearly complete structural restoration; F, omeprazole (OMP): Minor residual inflammation with mostly preserved glandular structure.

Treatment with NP50 resulted in the presence of abnormal glands with moderate epithelial erosion (C). Administration of NP100 led to a noticeable improvement in the lesions, with signs of epithelial tissue repair (D). In comparison, the NP200 restored normal epithelial structure (E), with the observation of typical gland formations.

In the OMP group (F), minimal gastric lesions were detected. The histopathological evaluation thus indicated that PAONP treatment mitigated the extent of destruction and necrosis of gastric tissue caused by ethanol. Consequently, the most significant reduction in gastric lesions was observed in groups treated with NP200, followed by NP100 and NP50, respectively.

5. Discussion

The PUs are prevalent, affecting approximately 5 - 10% of individuals during their lifetime (5). Throughout history, medicinal herbs have played a significant role in preventing and managing various diseases. Research has increasingly focused on the efficacy of different plant extracts in providing protection against gastric ulcers (32-35), contributing to the growth of phytochemical and phytopharmacological sciences. However, the large molecular size of bioactive compounds in these extracts can limit their absorption and gastroprotective effectiveness. To overcome this challenge, the integration of herbal medicine with nanotechnology through nanostructured systems has been proposed (36).

Pistacia atlantica oleoresin, traditionally utilized for gastrointestinal disorders, presents challenges related to its high viscosity and adhesive characteristics. The formulation of PAONPs may enhance the colon delivery of the oleoresin while reducing viscosity, thereby improving its effectiveness as a gastroprotective agent against gastric ulcers (37).

Recent research has shifted towards employing nanoparticles in drug delivery due to their numerous advantages over conventional methods. These benefits include a higher drug-load capacity, enhanced stability, increased specificity, faster dissolution rates in the bloodstream, improved absorption, and greater bioavailability. Additionally, nanoparticles facilitate controlled drug release, possess subcellular dimensions, exhibit biocompatibility, and can be administered through various routes, effectively delivering both hydrophilic and hydrophobic compounds. The increased surface area provided by nanoparticles also enhances the overall efficacy of the drugs (11, 12, 38).

This study utilized polymeric nanoparticles as drug delivery systems because of their suitable size and distribution. The dimensions of nanoparticles are critical in drug delivery applications, influencing targeting capabilities, toxicity, stability, drug loading, and release dynamics. A wide particle size distribution can lead to varied pharmacokinetics and release profiles. Consequently, systems with uniform particle sizes are preferred to ensure consistent conditions, controlled release, and predictable absorption kinetics, all of which are essential for effective drug delivery. While numerous studies have explored complex methods for the controlled synthesis of nanoparticles, such as microfluidics, these techniques are often intricate and costly. Our study employed nanoprecipitation, a straightforward, cost-effective, and single-step method that allows gentle formulation under ambient conditions without the need for chemical additives (surfactants or other polymers) or harsh processing conditions.

This method enables the synthesis of PAONPs with optimal size, high stability, and efficiency (27). The nanoprecipitation process involves dispersing a polymer solution into a large volume of a nonsolvent, resulting in the precipitation of the preformed polymer. This single-step experimental approach produces nanoparticles based on the solubility difference between the polymer in the solvent and the nonsolvent, typically water (39). Importantly, we used only the herbal compound without any additives to minimize the introduction of unwanted substances and reduce the potential side effects of the final drug. Notably, multiple variables influenced the size of the PAONPs and the nPDI. Therefore, it was essential to employ software to analyze each variable’s impact and interactions. For this purpose, we utilized Design Expert software to optimize the experimental results through mathematical modelling.

Our findings indicated that increasing the concentration of P. atlantica oleoresin in the presence of ethanol and acetone led to the formation of larger particles. This observation was attributed to the higher viscosity of the organic solution, which hindered its dispersion in water. Conversely, reducing the viscosity facilitated better dispersion of the organic solution, resulting in smaller PAONPs (40). Additionally, increasing the aqueous/organic volume ratio enhanced the dispersion of the organic solution in the aqueous phase, thereby yielding smaller PAONPs (41).

The results underscored the necessity of considering the interaction between experimental factors rather than analyzing them in isolation. For instance, when the aqueous/organic volume ratio was optimal (1/15), increasing the concentration resulted in smaller PAONPs. However, a lower ratio led to the formation of larger particles. This interaction suggests that independent manipulation of variables is insufficient for achieving optimal nanoparticle synthesis; hence, using a mathematical model was crucial for identifying the ideal parameters.

Although a complete phytochemical analysis of the harvested oleoresin was not conducted in this study, previous literature reports confirm the presence of major bioactive compounds such as α-pinene, monoterpenes, flavonoids, and phenolic compounds in P. atlantica oleoresin (6, 7). These constituents, known for their antioxidant and gastroprotective properties, formed the rationale for selecting this oleoresin for nanoformulation and the evaluation of its protective effects (6).

The FT-IR analysis confirmed the structural integrity of the synthesized PAONPs, indicating their potential as effective delivery agents. Zeta potential measurements affirmed the stability of the PAONPs, a vital characteristic for any drug delivery system. Morphological examination revealed that the synthesized PAONPs were spherical and hollow — a geometry that enhances drug loading capacity, making them promising candidates for pharmaceutical applications.

The current investigation demonstrated the gastroprotective activity of various doses of PAONPs, which exhibited a protective effect against ethanol-induced gastric ulcers in a dose-dependent manner. The PAONPs were administered orally at doses of 50, 100, and 200 mg/kg. A significant reduction in the Ulcer Index was observed following the administration of these PAONPs (P < 0.05) compared to the UC group, with the NP200 dose proving most effective in decreasing the Ulcer Index. These results indicate that the PAONPs substantially protected gastric tissue against ethanol-induced damage, proving more efficacious than the plant's essential oil. Microscopic evaluations corroborated these findings, showing decreased gastric lesions, reduced crypt damage, and less erosive and necrotic tissue.

The observed gastroprotective effects on PUs may stem from several mechanisms. One proposed mechanism involves the enhancement of prostaglandin synthesis, as suggested by Memariani et al. (6). Increased prostaglandin production can lead to elevated gastric pH, reduced gastric juice volume, inhibited leukotriene synthesis, and improved gastric cytoprotection (9), collectively contributing to wound healing.

Oxidative stress and the generation of free radicals are known to play a significant role in the development of gastric ulcers (42). Existing literature indicates that P. atlantica oil possesses antioxidant properties and potential gastroprotective effects (6, 43, 44). It is plausible that the PAONPs also enhance these gastroprotective properties. The primary component of the essential oil, α-pinene, is noted for its gastroprotective, anti-H. pylori, antibacterial, and wound-healing properties (6, 45).

Furthermore, P. atlantica resin may have implications in wound healing, as it has been shown to increase the concentration of basic fibroblast growth factor (bFGF) and platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF) (45, 46), both of which promote angiogenesis and facilitate the healing of ulcers (47). Thus, enhancing angiogenesis is another potential mechanism through which P. atlantica may contribute to gastric mucosal protection.

The resin may also exhibit anti-inflammatory effects, inhibiting inflammatory signals, reducing leukocyte infiltration, and limiting their interaction with blood vessel walls. However, further research is essential to elucidate its impact on gastric injury and healing processes (6).

Hajialyani et al. identified pharmacological targets for wound healing within herbal-based nanostructures, including modulation of anti-inflammatory cytokines, reduction of oxidative agents, promotion of neovascularization, and enhanced expression of growth factors such as VEGF, FGF, and PDGF. These mechanisms likely underlie the gastroprotective effects of PAONPs. Their study underscored the improved bioavailability, controlled release, and targeted delivery capabilities of plant extract nanostructures, emphasizing their potential as future pharmaceuticals for wound healing (48).

In summary, our findings align with previous research, highlighting that PAONPs represent a promising alternative gastroprotective strategy for gastric ulcers.

5.1. Conclusions

In conclusion, the results from this study confirm the gastroprotective activity of PAONPs. The synthesized PAONPs exhibited uniform size and distribution, characteristics that are favorable for effective drug delivery systems. Among the tested doses, NP200 proved to be the most effective in protecting against ethanol-induced gastric ulcers. Further pharmacological and clinical investigations are warranted to assess the safety, mechanisms, and efficacy of these PAONPs in preventing and managing PUs.