1. Background

The structure of the dermis has been shown to be reduced in density in adults, with total collagen levels decreasing by 1% annually throughout adult life (1). Skin collagen is less soluble in elderly people, exhibits less capacity for swelling, and is resistant to digestion by collagenase (2). In the aging process of skin, oxidative stress plays an essential role. Dermal collagen fibers become sparse, fragmented, and disorganized (3), and the production of collagen and the proportion of type I collagen to type III gently decrease with age (4-6) During extrinsic aging, skin collagens I, III, and VII are dramatically lost due to the activation of matrix metalloproteases (MMPs). This process is reinforced by the production of reactive oxygen species (ROS).

Due to the fact that a youthful appearance plays an important role in personality and social relationships (7), the demand for treatments to delay skin aging is increasing, and the use of nutritional supplements to modify the appearance and action of skin aging has been taken into consideration. Many dietary substances, such as vitamins, polyphenols, fatty acids, minerals, and proteins, have been shown to have a positive effect on aging skin (8-12). Collagen is commonly used in the pharmaceutical and makeup sectors. In the mesenchymal stem cell scaffold and extracellular biometric matrix, collagen's pharmacological activity is designed to boost cell growth and development (13). Generally, the original sources of collagen are pig skin and cattle. However, the incidence of bovine spongiform encephalopathy (BSE) has led to concern among consumers of cow gelatin. In addition, collagen derived from pig bone is not used by many people due to religious restrictions (13). Therefore, there is a need for alternative collagen sources. Marine organisms are known as potential alternative sources due to their availability, lack of food restriction, risk aversion, and high collagen production (14). In recent years, fish scales have been investigated as a potential source of collagen type I for preparation because fish scales have a significant amount of collagen type I (15-19). In addition, collagen is isolated from various species of marine invertebrates, including sea bells, sponges, mistletoe, and echinoderms such as sea cucumbers, which are used in various pharmaceutical, cosmetic, and food industries. Marine collagen products increase fiber density in the skin, reduce cholesterol, and enhance skin rejuvenation (20). Crude protein in the body of sea cucumbers can reach 83% of its dry weight, of which 70% of this protein forms collagen (21, 22). Since there are some limitations in using common collagen sources and a high amount of collagen in the sea cucumber body wall, without risk of disease for humans, it can be used as a source of collagen for pharmaceutical and medical research.

2. Objectives

In the present study, the effects of collagen extracted from the sea cucumber Holothuria leucospilota (a dominant Persian Gulf species) on the histological appearance and ROS levels of aged mice skin have been investigated.

3. Methods

A total of 20 tropical sea cucumbers, H. leucospilota, weighing 100 ± 20 g, were collected from the tidal zone of the Persian Gulf coast and provided by the Persian Gulf Molluscs Research Station. H. leucospilota were placed in an icebox and transferred to the research center.

3.1. Preparation of Crude Collagen Fibril

For extracting sea cucumber crude collagen fibril (CCF) with slight modifications, the water-EDTA-water method was applied as previously reported by Cui et al. (23). The body wall of H. leucospilota was cut into small fragments and then washed several times using deionized water. The samples, 100 g wet weight, were then stirred in 1 L of deionized water for 30 minutes and repeated several times. The water was subsequently replaced with 1 L of EDTA (4 mM, dissolved in 0.1 M Tris-HCl, pH 8.0), and the samples were stirred overnight. The liquid solution was discarded and washed with 1 L of deionized water several times. After decanting the water, 500 mL of fresh deionized water was added to the samples and stirred for 48 hours to provide a homogeneous mixture. Then, the obtained mixture was centrifuged at 10,000 g for 5 minutes. The supernatant containing free collagen fibrils was collected. To collect more collagen fibrils, 500 mL of deionized water was added to the precipitate and stirred for 48 hours. The samples were centrifuged at 10,000 g for 5 minutes, and the supernatant was collected. All collected supernatants were centrifuged at 15,000 g for 30 minutes, and the obtained precipitate was called CCF. Finally, the collected CCFs from previous steps were lyophilized and stored at -20°C.

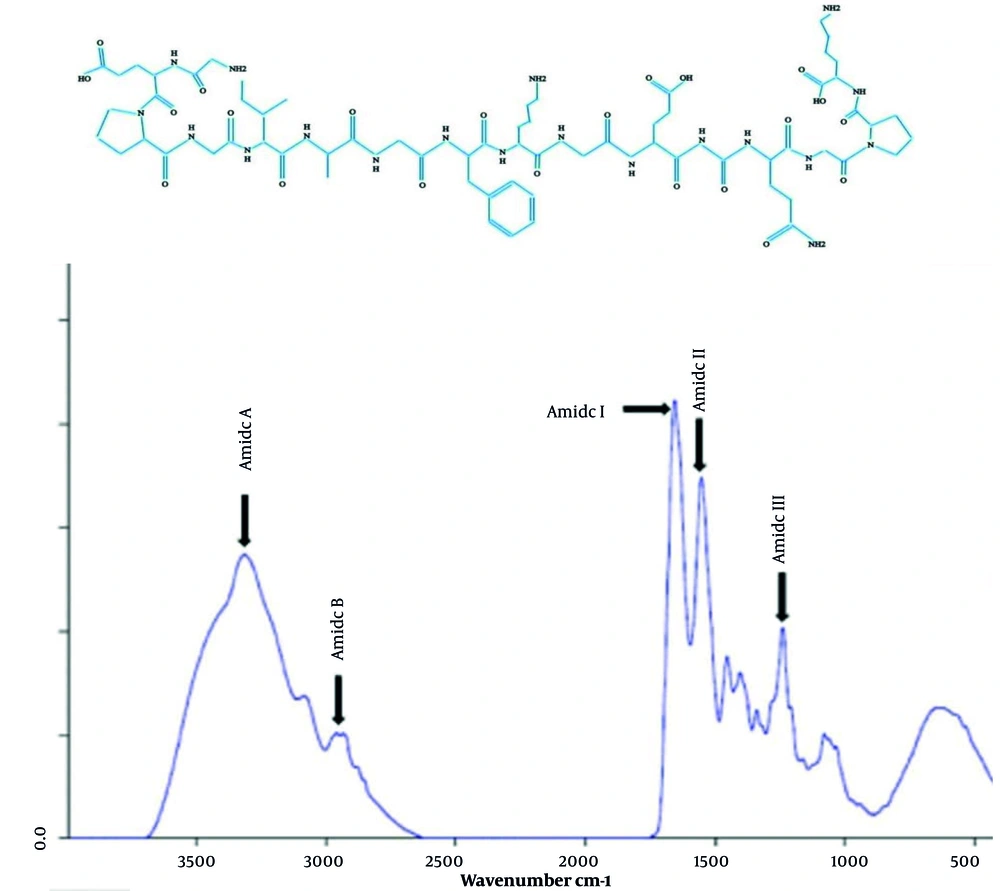

3.2. Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy

A Bruker infrared spectrophotometer, Vertex 70 (Germany), was used for measuring Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR) spectra with the potassium bromide (KBr) disk method, in which a 0.2 mg collagen sample was ground together with KBr powder (10 mg) under dry conditions. Infrared spectra were recorded from 500 to 4000 cm-1 at a data acquisition rate of 2 cm-1 per point. The spectra curve results were provided using Opus 7.

3.3. Cream Formulation

A semisolid emulsion cream based on oil in water (O/W) was formulated. In the oil phase, or part I, the emulsifier (stearic acid) and other oil-soluble ingredients (cetyl alcohol, lanolin, spermaceti wax, and triethanolamine) were mixed and heated to 75°C. The preservatives and other water-soluble components (methyl paraben, glycerol, collagen, and borax) were mixed and heated to 75°C in the aqueous phase, or part II. After heating, the aqueous phase was added in portions to the oil phase with continuous stirring until the cooling of the emulsifier took place. The formula for the cream is presented in Table 1. Different formulations were evaluated based on their appearance, pH determination, homogeneity, and spreadability, and the best formula was chosen as the baseline formula.

| Ingredients | Formulation (% w/w) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| F1 | F2 | F3 | F4 | |

| Collagen | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| Bees wax | 15 | 10 | 10 | 15 |

| Spermaceti | 4 | 7 | 2 | 4 |

| Liquid paraffin | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 |

| Borax | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 |

| Parabens (total) | 0.25 | 0.25 | 0.25 | 0.25 |

| Glycerol | 5 | 5 | 5 | 15 |

| Triethanolamine | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 |

| Cetyl alcohol | 4 | 4 | 2 | 4 |

| Stearic acid | 8 | 8 | 4 | 8 |

| Lanolin | 4 | 4 | 2 | 4 |

| Water (qs, 100) | Qs | Qs | Qs | Qs |

3.4. Thermal Change Test

Three samples, each weighing 20 g, of each formulation (or base) were selected and stored at 4 - 6°C, 25°C, and 45 - 50°C. The stabilities and appearances of the samples were evaluated at 24 hours, one month, and three months post-formulation.

3.5. Creaming and Coalescence

A total of 10 g from each formulation was poured into a flask and stored at room temperature for 3 months. The physical stabilities of the formula were determined at one week, one month, and three months post-storage.

3.6. Centrifugation

Ten grams of each formulation was poured into a centrifuge tube (1 cm diameter) and centrifuged at 2000 rpm for 15 minutes. The phase separation and solid sedimentation of the samples were evaluated.

3.7. Determination of pH

For the measurement of pH, a suspension consisting of a 1% KNO3 solution was prepared from each sample. The mixture was stirred by a magnetic stirrer for homogeneity, and its pH was measured. The pH was determined at 48 hours, one week, and three weeks after preparation.

3.8. Viscosity Determination

The rheological behaviors of the samples were studied using a Brookfield viscometer (model DV-I with No. 6 spindle). Each sample was poured into a flask, and spindle velocity was raised to determine the viscosity at three speeds: 0.5, 1, and 1.5 rpm.

3.9. Animals and Experimental Design

Seventy-two healthy female NMRI mice from a breeding colony (38 ± 4 g, 8 months old) were provided by the Laboratory Animal Research Center, Jundishapur Medical Sciences University, Ahvaz, Iran. All animal experiments were carried out in accordance with standard guidelines for the care of animals, which were approved by the Research Center and Experimental Animal House, Ahvaz Jundishapur University of Medical Sciences. All mice were housed in cages and allowed free access to diet and water. The temperature of the animal room was maintained at 22 ± 2°C, with relative humidity between 40% and 70%, and it was artificially illuminated with a 12-hour light/dark cycle (without any ultraviolet emission).

After acclimatization for one week, the dorsal aspect of the neck was epilated using 6% (w/w) sodium sulfide, and the animals were randomly divided into the following six groups (12 mice per group):

- Group 1: Control, without treatment.

- Group 2: Cinere anti-wrinkle cream (Cinere, Yassuj, Iran).

- Group 3: Collagen cream 2%.

- Group 4: Collagen cream 2.5%.

- Group 5: Collagen cream 3%.

- Group 6: Placebo cream (collagen cream base).

Animals received the treatment creams locally for one month, twice a day. After anesthesia, the skin of the neck was removed and kept in 10% formalin buffer and at -20ºC for histopathological and antioxidant evaluation on days 7, 15, 23, and 30, respectively.

3.10. Antioxidant Indicators Analysis

Skin tissues were powdered in a liquid nitrogen bath and homogenized with 600 µL of phosphate buffer solution (PBS). Homogenate samples were centrifuged at 6000 g for 10 minutes to collect the supernatants. The Bradford method was used for measuring the total protein concentration of each sample. The total antioxidant capacity (T-AOC) and superoxide dismutase activity (SOD) were determined using colorimetric kits according to the manufacturer's protocols (ZellBio GmbH Company, Germany). Malondialdehyde (MDA)formation was also recorded using thiobarbituric acid reactive substances (TBARS) assay methods as previously reported by Hassanpour et al. (24). The results were expressed in U/mg protein or nmol/mg protein according to the manufacturer's guidance.

3.11. Thiobarbituric Acid Reactive Substances Assay

All reagents for this assay were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA). Using the TBARS method, MDA, an indicator of lipid peroxidation, was measured according to Hassanpour et al. (24). For precipitating protein, Cl3CCOOH was used and added to the skin tissue lysate. The obtained supernatants were recovered by centrifugation. An equal volume of TBA was then added to each sample and incubated in a boiling water bath for 10 minutes. After cooling the samples, absorbance was measured at 532 nm using a spectrophotometer (Corning 480, USA). The TBARS data were calculated and expressed as nanomoles per milligram of total protein of the tissue sample.

3.12. Histopathological Analysis

Out of each group, 3 fixed skin samples (1 cm2) were embedded in paraffin wax and sectioned at 5 μm in thickness. Serial sections were placed onto slides and stained with hematoxylin-eosin (HE), Masson’s trichrome, and Verhoeff-van Gieson (VG). All stained samples were blindly analyzed by an expert pathologist using a light microscope (Olympus, Japan). Maturation and organization of collagen, elastic fibers, and collagen content were the criteria for histopathological investigation.

3.13. Statistical Analysis

Results are reported as means ± standard error of the mean (SEM). Using SPSS version 22, the data were analyzed, and the differences between means of the individual groups were assessed using analysis of variance (ANOVA), followed by Tukey's HSD test. Differences were considered statistically significant at P < 0.05. The mean percentage of collagen content from the first to fourth weeks post-treatment in each group was analyzed using repeated-measure ANOVA.

4. Results

4.1. Characterization Findings of Formulas

The results of pH, appearance, physicochemical properties, and stability of formulations showed that the best formulation physicochemical properties belonged to F1. The results of the physicochemical properties of various formulas are presented in Table 2.

| Formulations | pH (Mean ± SD) | Homogenity | Spreadability | Removal | Appearance | Palpable Particles |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| F1 | 8.08 ± 0.03 | Good | Good | Easy | Relatively dark | No particle |

| F2 | 8.15± 0.02 | Good | Poor | Easy | Relatively dark | No particle |

| F3 | 8.51± 0.03 | Fairly good | Good | Easy | Relatively dark | Contains a particle |

| F4 | 8.01 ± 0.03 | Good | Poor | Easy | Relatively dark | No particle |

4.2. Characterization of Cream-Based F1 Formula Containing Collagen

With stability and experimental inspection determination of creams, a homogeneous appearance was shown without any creaming or coalescence during the 3-month storage period, as well as no change in the appearance of the formula during centrifugation, viscosity, and thermal cycle tests (Table 3).

| Formulations; Shear Rate (rpm) | Viscosity (cps) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| After 2 Days | After 1 Month | After 3 Months | |

| Collagen cream 2% | |||

| 0.5 | 457.00 ± 0.02 | 465.00 ± 0.01 | 463.00 ± 0.02 |

| 1 | 299.00 ± 0.01 | 305.00 ± 0.00 | 301.00 ± 0.05 |

| 1.5 | 214.00 ± 0.01 | 223.00 ± 0.03 | 216.00 ± 0.05 |

| Collagen cream 2.5% | |||

| 0.5 | 547.00 ± 0.03 | 578.00 ± 0.01 | 553.00 ± 0.03 |

| 1 | 303.00 ± 0.04 | 313.00 ± 0.00 | 309.00 ± 0.00 |

| 1.5 | 222.00 ± 0.00 | 231.00 ± 0.05 | 226.00 ± 0.01 |

| Collagen cream 3% | |||

| 0.5 | 743.00 ± 0.02 | 753.00 ± 0.01 | 751.00 ± 0.02 |

| 1 | 321.00 ± 0.01 | 332.00 ± 0.01 | 326 .00± 0.00 |

| 1.5 | 217.00 ± 0.00 | 224.00 ± 0.02 | 219.00 ± 0.01 |

a Values are expressed as mean ± SD.

4.3. Assessment of Lipid Peroxidation, Total Antioxidant Capacity, and Superoxide Dismutase Activity

Results of MDA, T-AOC, and SOD activities are presented in Tables 4. - 6. There was no significant difference between all groups in terms of T-AOC at all time periods.

| Groups | MDA Content (nmol/mg Protein) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1th Week | 2nd Week | 3rd Week | 4th Week | |

| Collagen cream 2% | 2.94 ± 1.15 A | 5.29 ± 1.50 | 4.90 ± 1.47 | 8.59 ± 2.48 A |

| Collagen cream 2.5% | 7.02 ± 1.90 A, B | 3.88 ± 1.30 | 6.65 ± 1.73 | 5.89 ± 2.01 A |

| Collagen cream 3% | 18.61 ± 6.10 B | 6.08 ± 1.84 | 6.54 ± 1.52 | 8.59 ± 1.63 A |

| Pelacebo | 4.38 ± 1.44 A | 6.38 ± 1.37 | 9.39 ± 2.80 | 9.05 ± 2.58 A |

| Cinere cream | 3.82 ± 1.42 A | 6.92 ± 2.35 | 5.04 ± 1.09 | 10.46 ± 3.03 A |

| Control | 5.04 ± 1.51 A | 6.72 ± 1.62 | 10.29 ± 3.53 | 9.40 ± 2.31 A |

Abbreviation: MDA, malondialdehyde.

a Values are expressed as mean ± SD.

b Means followed by different capital letters in a column are significantly different at P < 0.05.

| Groups | SOD Activity (U/mg Protein) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1th Week | 2nd Week | 3rd Week | 4th Week | |

| Collagen cream 2% | 74.27 ± 29.54 | 46.60 ± 5.11 | 34.91 ± 2.02 | 25.37 ± 1.80 D |

| Collagen cream 2.5% | 34.79 ± 6.45 | 49.39 ± 0.94 | 80.57 ± 27.12 | 17.81 ± 6.53 B, D |

| Collagen cream 3% | 94.93 ± 24.49 | 74.04 ± 17.00 | 55.45 ± 13.57 | 100.90 ± 7.69 A, C |

| Pelacebo | 59.90 ± 13.50 | 66.35 ± 12.34 | 70.64 ± 8.34 | 61.13 ± 8.21 A, B, C, D |

| Cinere cream | 75.46 ± 13.97 | 68.77 ± 7.68 | 89.59 ± 18.48 | 46.02 ± 11.79 B, D |

| Control | 73.50 ± 10.53 | 41.43 ± 34.60 | 43.79 ± 3.45 | 89.30 ± 9.61 A |

Abbreviation: SOD, superoxide dismutase.

a Values are expressed as mean ± SD.

b Means followed by different capital letters in a column are significantly different at P < 0.05.

| Groups | T-AOC (nmol/mg Protein) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1th Week | 2nd Week | 3rd Week | 4th Week | |

| Collagen cream 2% | 459.05 ± 124.17 | 406.10 ± 67.84 | 638.33 ± 74.02 | 698.02 ± 61.99 |

| Collagen cream 2.5% | 344.35 ± 24.34 | 434.02 ± 49.89 | 721.86 ± 29.63 | 394.31 ± 55.88 |

| Collagen cream 3% | 505.68 ± 66.55 | 459.07 ± 60.20 | 406.9 ± 973.79 | 775.64 ± 259.99 |

| Placebo | 345.97 ± 54.14 | 462.81 ± 21.32 | 512.33 ± 258.34 | 679.11 ± 67.71 |

| Cinere cream | 397.38 ± 45.64 | 579.69 ± 134.68 | 535.14 ± 96.14 | 708.80 ± 166.41 |

| Control | 399.52 ± 30.36 | 288.99 ± 39.70 | 538.29 ± 67.27 | 698.73 ± 71.71 |

Abbreviation: T-AOC, total antioxidant capacity.

a Values are expressed as mean ± SD.

The MDA content was significantly decreased in the skin treated with 3% collagen cream compared to the control and other treatment groups (P < 0.05) at the first week post-treatment. There was no significant difference between all groups at other times in terms of MDA level.

Except for the 2.5% collagen cream, no significant difference between treatment groups was seen in terms of SOD activity in the first week post-treatment. The 2.5% collagen cream showed significantly lower SOD activity than those of other treatment groups (P < 0.01). However, a significant decrease in SOD activity was seen in the 2.5% collagen cream compared to the control (P = 0.001) and 3% collagen cream (P = 0.001) groups at the fourth week post-treatment. Moreover, the SOD activity of the 2% collagen cream and Cinere cream groups was significantly decreased compared to the control group (P = 0.002).

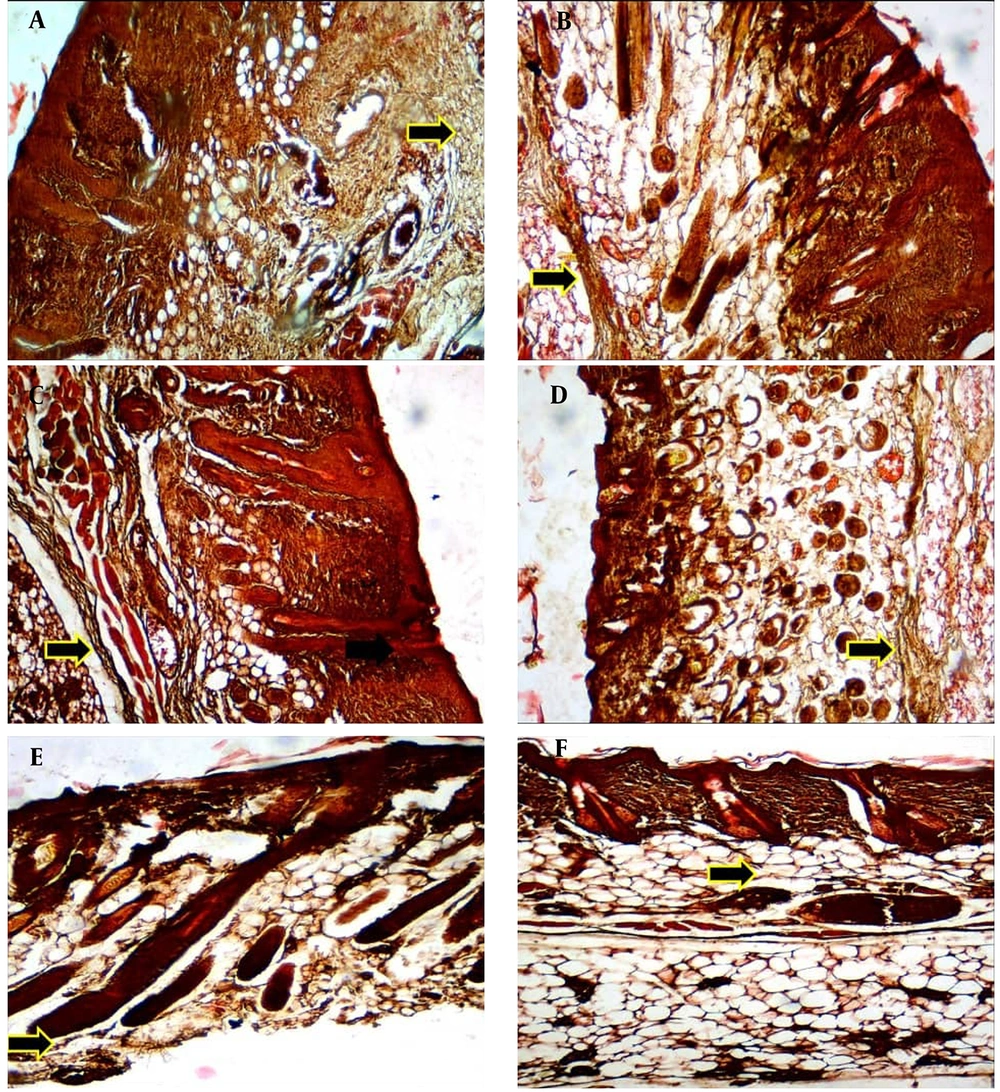

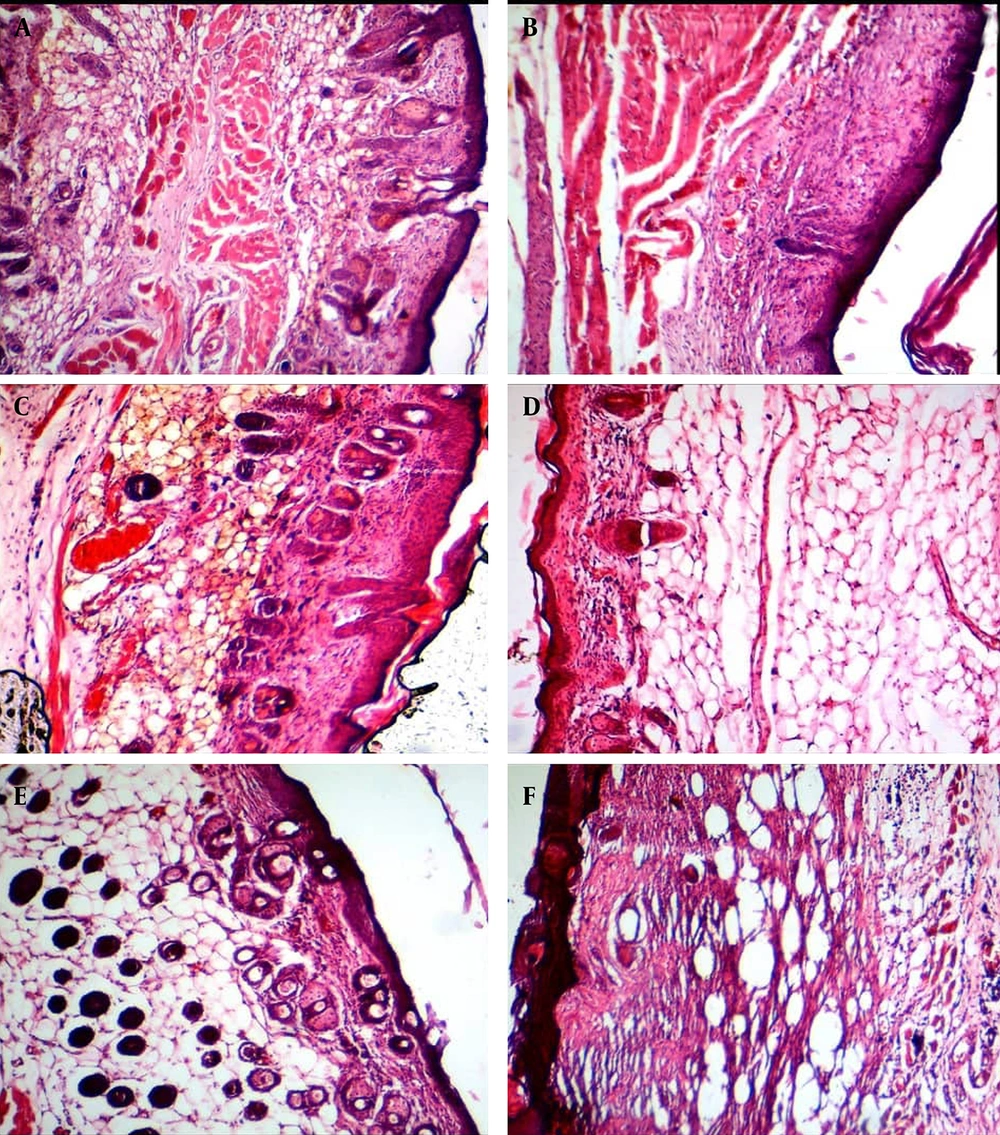

4.4. The Effects of Treatment Cream on Histological Changes in Aged Mice’s Skin

Histologically, the effects of various treatments on collagen and elastic fiber arrangement in the aged mice’s skin were evaluated using Verhoeff, Masson's trichrome green, and H&E staining. Verhoeff staining showed that the elastic fibers were denatured, thin, and irregular within the dermis in all groups at the first and second weeks post-treatment, as well as in the control and placebo groups at all four interval times. The collagen-based cream groups, particularly the 2.5% collagen, showed less denatured elastic fibers than those in the control and placebo groups at the fourth week post-treatment. However, the best elastosis and regular elastic fibers with less denaturation were seen in the 2.5% collagen-based cream, followed by 2% and 3% collagen, and Cinere at the fourth week post-treatment (Figure 1).

Masson's trichrome and H&E staining also showed that the collagen fibers were thin, irregular, unorganized, and appeared short within the dermis in all groups at the first (Figure 2) and second weeks of treatment. While the collagen fibers became regular, thickened, organized, and bundle-shaped in the collagen-based cream groups compared to the control group at the fourth week post-treatment.

Masson's trichrome staining showed that the collagen fibers were thin, irregular, unorganized, appeared short, and twisted within the dermis in all groups at the first week of treatment, as well as in the control and placebo groups. 2% collagen (A); 3% collagen (B); control (C); 2.5% collagen (D); Cinere (E); and placebo (F).

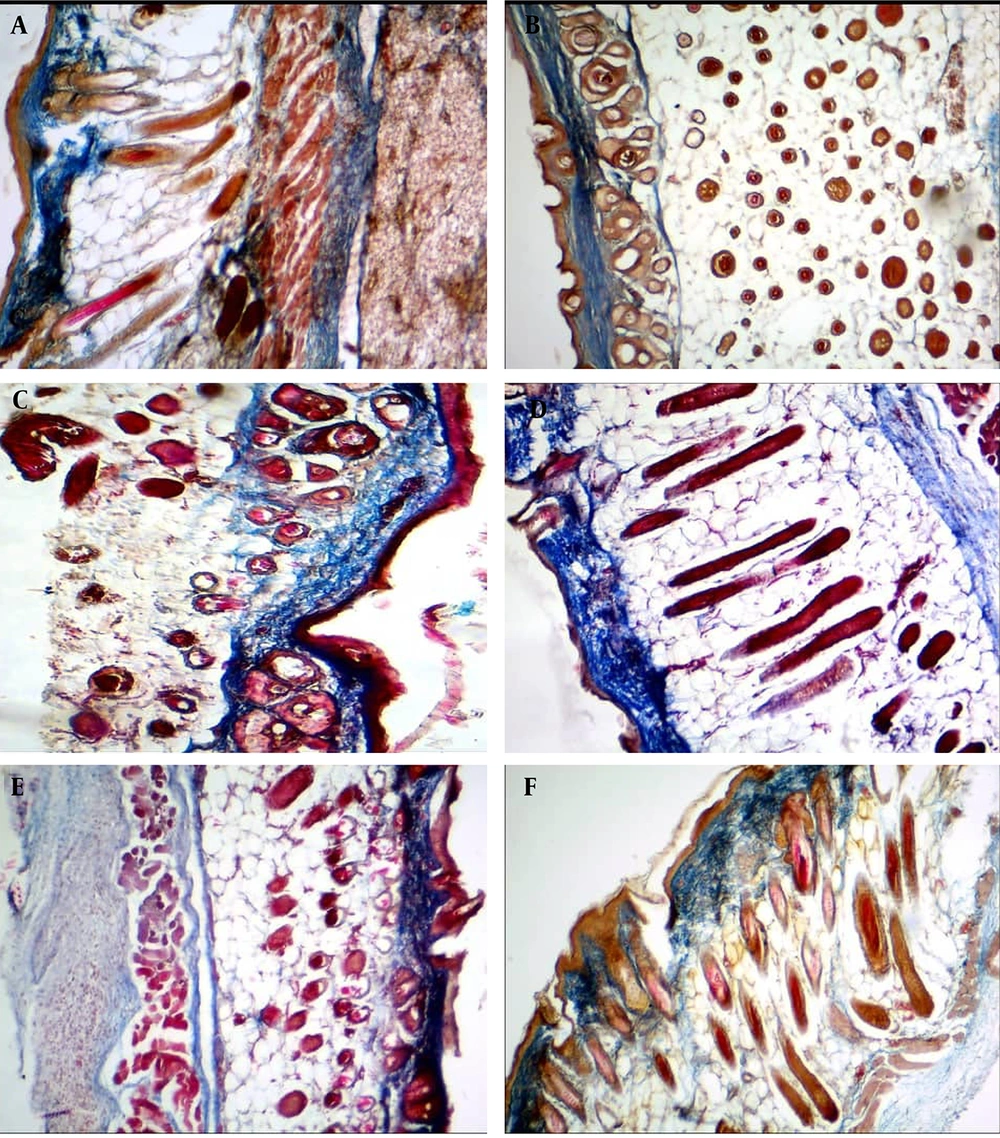

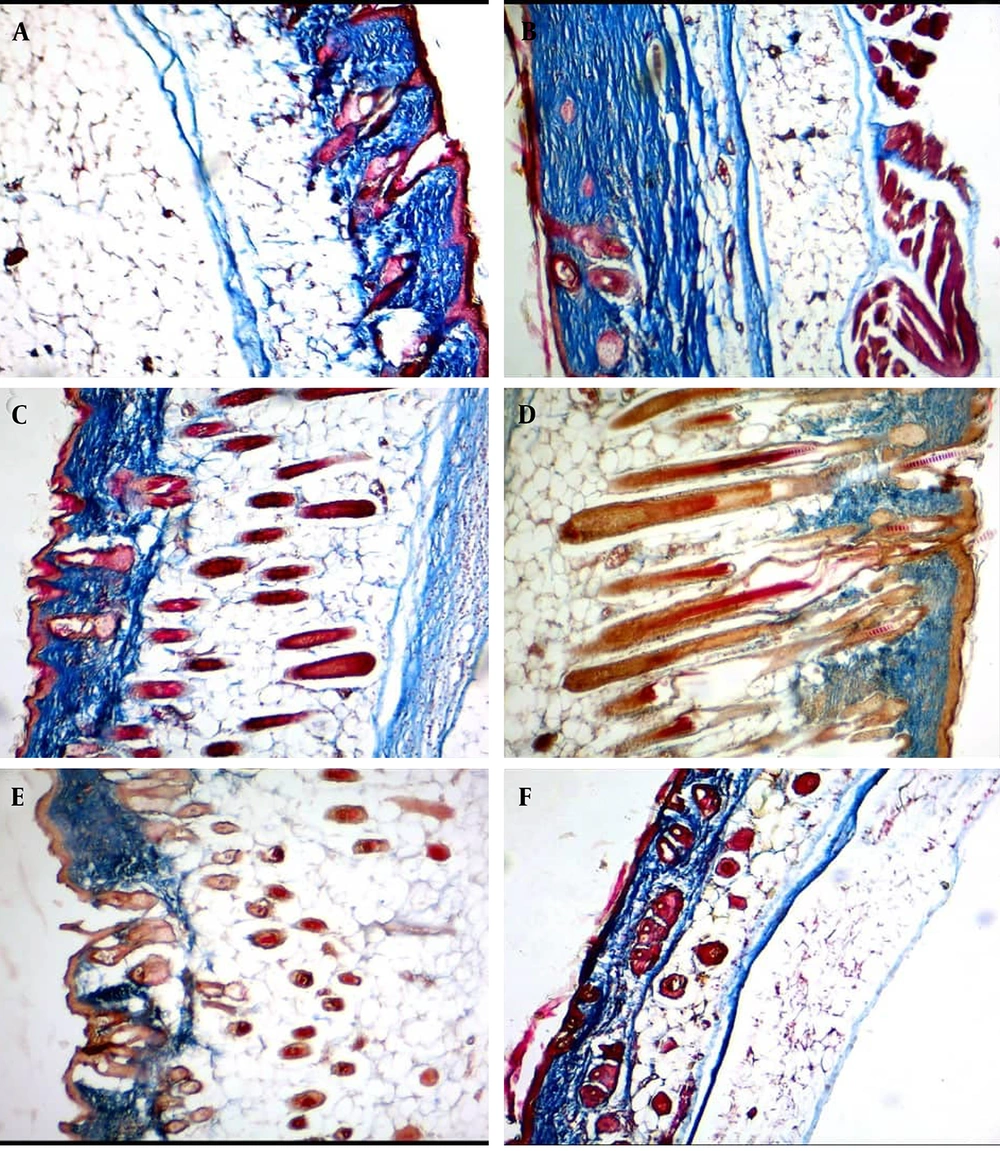

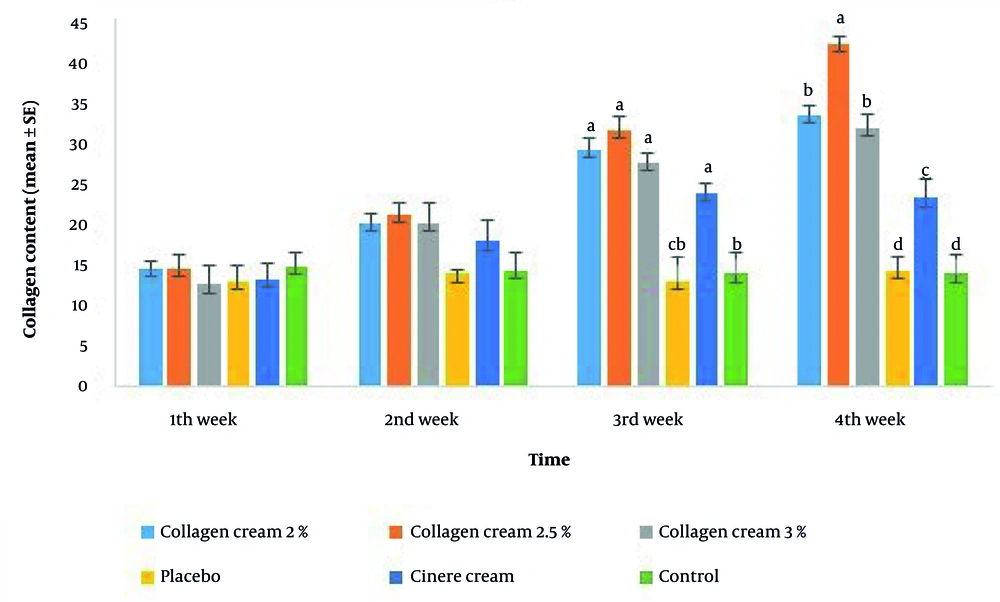

However, the best histological appearance of collagen fibers was seen in the 2.5% collagen-based cream, followed by 2% and 3% collagen, Cinere, the placebo, and the control groups at the fourth week post-treatment (Figures 3 and 4). The mean percentage of skin collagen fiber content was also measured in various groups stained by Masson’s trichrome using ImageJ software (Figure 5). The results of skin collagen fiber content in various groups are shown in Table 7.

With Masson's trichrome staining, the collagen fibers became regular, thickened, organized, and bundle-shaped in the collagen-based cream groups compared to the control group at the fourth week post-treatment. The best histological appearance of collagen fibers was seen in the 2.5% collagen-based cream (A), followed by 2% collagen (B), 3% collagen (C), Cinere (D), placebo (E), and the control (F) at the fourth week post-treatment.

H&E staining showed that the collagen fibers became regular, thickened, organized, and bundle-shaped in the collagen-based cream groups compared to the control group at the fourth week post-treatment. The best histological appearance of collagen fibers was seen in the 2.5% collagen-based cream (A), followed by 2% collagen (B), 3% collagen (C), Cinere (D), placebo (E), and the control (F) at the fourth week post-treatment.

The mean percentage of collagen content in various groups at four interval times post-treatment: Intergroup comparison at any interval time post-treatment in terms of the mean percentage of collagen content is shown statistically. Different letters without common letters above each column indicate a significant difference at the P < 0.05 level.

| Groups | Collagen Content (The Mean Percentage ± SEM) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1th Week | 2nd Week | 3rd Week | 4th Week | |

| Collagen cream 2% | 14.66 ± 0.88 D | 20.33 ± 1.20 C | 29.33 ± 1.45 B, A | 33.66 ± 1.20 A |

| Collagen cream 2.5% | 14.66 ± 1.76 C | 21.33 ± 1.45 C | 31.66 ± 1.76 B | 42.33 ± 0.88 A |

| Collagen cream 3% | 12.66 ± 2.40 C | 20.33 ± 2.33 B, C | 27.66 ± 1.20 B, A | 32.00 ± 1.73 A |

| Placebo | 13.00 ± 2.08 A | 14.00 ± 0.57 A | 13.00 ± 3.21 A | 14.33 ± 1.76 A |

| Cinere cream | 13.33 ± 1.85 B | 18.00 ± 2.51 A, B | 24.00 ± 1.15 A | 23.33 ± 2.33 A |

| Control | 15.00 ± 1.73 A | 14.33 ± 2.18 A | 14.00 ± 2.51 A | 14.00 ± 2.30 A |

Abbreviation: SEM, standard error of the mean.

a Values are expressed as mean ± SD.

b Means followed by different capital letters in a column are significantly different at P < 0.05.

4.5. Analysis of Fourier Transform Infrared Spectra

The FTIR spectra of CCF are observed in Figure 6. The characteristic amide bands for collagen, including amides A, B, I, II, and III, were shown in this study. Collagen is composed of polypeptide chains, so the presence of various amide groups indicates these functional groups and confirms the structure of collagen (2). For example, a part of the structure of collagen type I, which is predominant in animal skin, is shown below.

5. Discussion

In the current study, we formulated four bases of cream according to pH, appearance, physicochemical properties, and stability for adding collagen as an anti-wrinkle agent. The best base cream was selected, and the extracted collagen from H. leucospilota was then added to it at three concentrations of 2%, 2.5%, and 3%. To characterize the collagen isolated from H. leucospilota, FTIR was performed. Also, to confirm the stability of this collagen-based cream, its viscosity was measured. No change in the appearance of the formula during centrifugation, viscosity, and thermal cycle tests was detected during the 3-month storage period, indicating the stability of the formulated creams.

Therefore, the primary aim of this research was to evaluate the anti-wrinkle and antioxidant effects of our formulated collagen-based creams isolated from H. leucospilota at various concentrations for the first time. Another goal of the present study was to compare the collagen-based cream’s anti-wrinkle effect with the commercial Cinere cream. We used sea cucumbers in our study because they are rich in bioactive compounds, including collagen, saponin, chondroitin sulfate, amino acids, and phenols. They can also be used without risk of disease for humans (25-27). Histologically, the thick, regular, and bundle shapes of both collagen and elastic fibers within the dermis in the collagen-based cream groups at the fourth week post-treatment were one of the main findings of the present study. The mean percentage of skin collagen fiber content was significantly increased in the collagen-based cream groups compared to the Cinere and control groups at the fourth week post-treatment. Based on this finding, the 2.5% collagen-based cream showed the best quantity and quality of collagen content in the dermis, as well as the quantity of elastic fibers, followed by 2% and 3%, compared to other groups. This finding was in accordance with the obtained data from the mean percentage of collagen content.

The natural aging process has been known to correlate with alterations in the structural and mechanical integrity as well as the composition of the connective tissue (28). Collagens are not only the most abundant matrix proteins but also provide the overall stiffness of tissues such as skin (28, 29). The basic part of the dermis is collagen and elastic fibers. Collagen is an insoluble protein that constitutes 75% of the dermis’s dry weight (5). Collagen has been observed to improve the laxity of the skin and decrease the appearance of wrinkles (30, 31). Wrinkles are induced by a loss of elasticity due to reduced collagen content, which is linked to skin dermal tissue elasticity (32).

In the current study, the highest mean percentage of collagen content belonged to the 2.5% collagen at four weeks post-treatment. The antioxidant activity of the formulated collagen-based creams was another main finding of the present study. The decreased MDA content as well as SOD activity in the skin treated with collagen-based cream, particularly the 2.5% and 3% collagen creams, compared to the control and other treatment groups at the fourth week post-treatment, indicates the antioxidant activity of our formulated cream from H. leucospilota.

Saponins are the main bioactive metabolite compounds found in sea cucumbers such as Holothuroidea spp. (26). The anti-aging effect of compounds containing saponin on the skin of a mouse-aging model has been demonstrated to be closely related to oxidative damage (27). The increase in oxidative stress production has played an important role in the rate and hallmark of aging (33).

5.1. Conclusions

In conclusion, the collagen-based cream from H. leucospilota has an anti-wrinkle effect and improves the laxity of aged skin by enhancing skin collagen content. This effect can contribute to increased activity of antioxidant agents, such as SOD, and decreased levels of oxidative stress and ROS production, as indicated by diminished levels of MDA. These findings suggest that collagen-based cream from H. leucospilota has potential capacity for use against skin aging in a mouse model.