1. Background

There are several systems for categorizing pain; the most common of them are acute and chronic pain. After tissue injury, acute pain develops rapidly and lasts just a short time. Chronic pain, on the other hand, is associated with tissue injury, has a longer duration than acute pain, and conventional medications may be ineffectual or have side effects (1). For example, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) cause gastrointestinal issues, including small bowel enteropathy and foregut symptoms, such as peptic ulcer disease (2). In addition, pain is classified as nociceptive or neuropathic based on neuronal involvement. The initiation of primary nociceptive afferents by current or prospective tissue-damaging stimuli causes nociceptive pain, also known as physiologic pain. Nociceptive pain occurs when sensory receptors in intact visceral and somatic tissues are activated, so large nerve integrity is retained. In contrast, neuropathic pain typically involves nerve damage or dysfunction, which disrupts normal nerve structure and function (3). The formalin test refers to the quantification of nociceptive behaviors in response to intradermal/subcutaneous (S.C.) formaldehyde injected into the plantar/dorsal hindpaw of rodents (4).

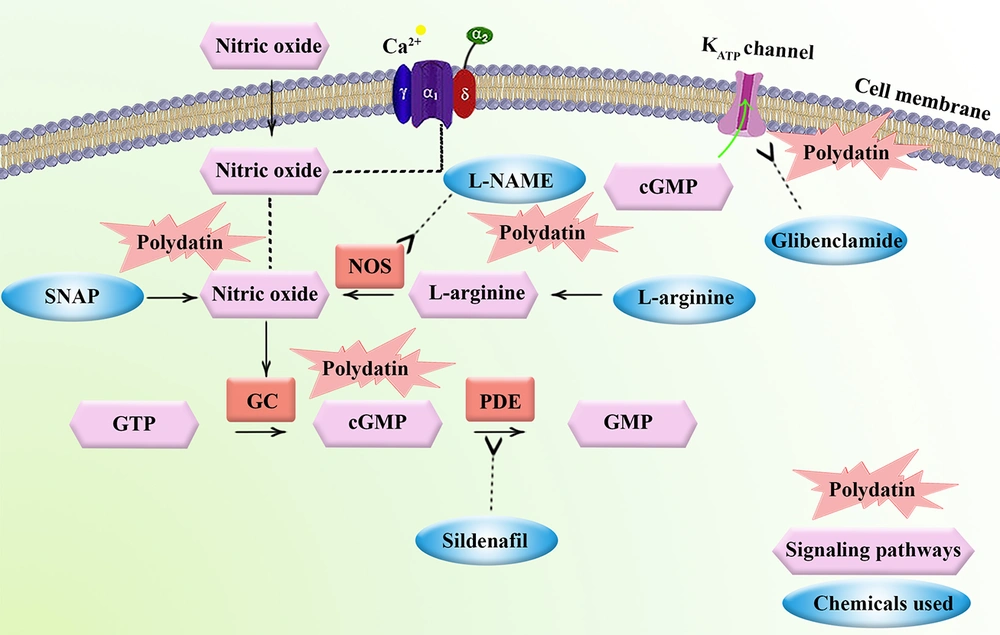

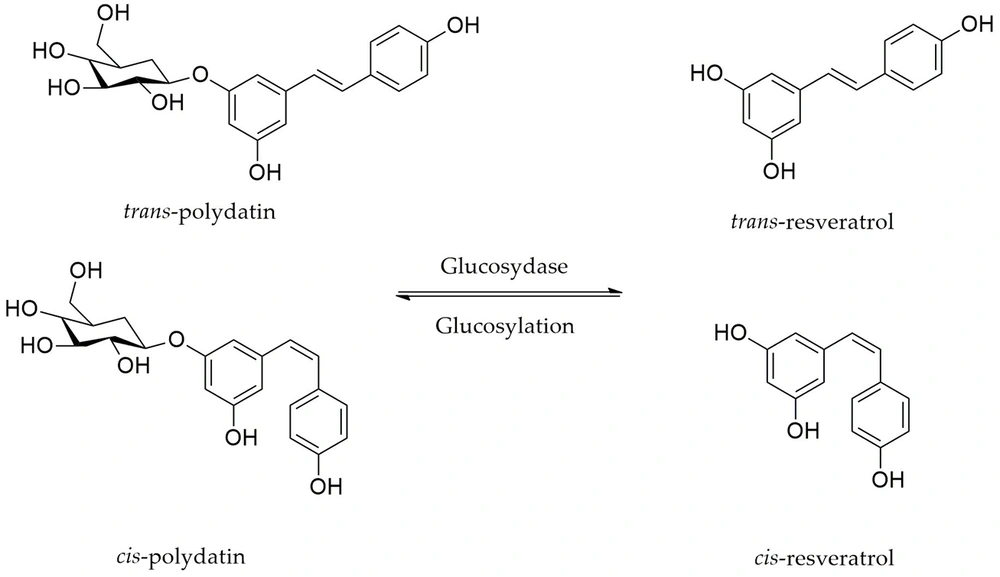

Tissue injury causes the production of cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2) and prostaglandins, bradykinin, substance P, serotonin, and histamine, which enhance the activity or irritation of the pain receptors and produce action potentials. Moreover, NGF signaling and L-arginine (L-Arg)/3',5'-cyclic GMP (cGMP)/ATP-sensitive potassium channel (KATP) pathways play important roles in pain modulation (5). It has been reported that nitric oxide (NO), cGMP, KATP, and the associated NO/cGMP/KATP signaling pathway influence the level of pain and mediate anti-nociceptive action (6). Clinical and preclinical findings highlight the therapeutic importance of this pathway, demonstrating that NO donors and activation of the NO/cGMP/protein kinase G (PKG)/KATP signaling cascade effectively alleviate pain in diverse models of inflammatory, neuropathic, and chronic pain (7). In this context, KATP channels are critical for pain processing. The KATP channel inhibitors, on the other hand, may reduce analgesic properties (8). A systematic review confirms that KATP channel openers significantly attenuate induced pain in various animal models and potentiate the efficacy of analgesic drugs. These channels are expressed at multiple levels of the pain pathways and represent potential drug targets for novel pain therapies (9). Pretreatment with L-Arg, on the contrary, improves a substratum for nitric oxide generation (NOS). As a result, some information has shown that L-Arg/NO/cGMP/KATP channel signaling pathways have a critical function in the anti-nociceptive responses to both major kinds of painkillers, narcotic drugs, and NSAIDs (10, 11). Considering the complex mechanisms behind nociceptive pain, researchers are trying to find novel multi-targeting agents with higher efficacy and fewer side effects in combating nociceptive pain. Polydatin, commonly known as resveratrol-3-mono-d-glucoside, is a naturally occurring resveratrol glucoside with the chemical formula 3, 4′,5-trihydroxystilbene-3-d-glucoside (Figure 1).

Grape juice and red/white wines represent the most prevalent origins of polydatin (12). Research has demonstrated polydatin’s therapeutic potential across a range of conditions, including various cancers, cardiovascular diseases, diabetes, neurological disorders, and both hepatic and respiratory diseases. Polydatin has also shown promise in managing gastrointestinal issues, infectious diseases, rheumatoid conditions, and skeletal/women's disorders (13). Moreover, polydatin has been shown to effectively suppress inflammatory processes, reduce oxidative stress, and prevent apoptosis (14, 15). Notably, it exhibits superior antioxidant (16) and anti-inflammatory (17) effects compared to resveratrol, along with enhanced biodistribution and intestinal absorption due to its sugar moieties (18). Pharmacokinetic studies employing sensitive analytical techniques such as liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) and high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) have demonstrated polydatin’s improved biodistribution by accurately quantifying its absorption, plasma concentration, half-life, and bioavailability in vivo. Enhanced biodistribution indicates that polydatin is more efficiently absorbed, sustains longer circulation within the bloodstream, and achieves greater tissue penetration, which — together with its potent antioxidant properties — underpins its superior therapeutic efficacy (19, 20).

We also previously showed the neuroprotective role of polydatin (14). A study has investigated polydatin’s impact on pain and anxiety-like behaviors induced by inflammatory stimuli, such as complete Freund’s adjuvant, revealing these effects through the suppression of pro-inflammatory cytokines in the amygdala (21). Furthermore, research on spinal cord injury models demonstrated polydatin’s ability to improve sensory-motor functions by reducing oxidative stress and inflammation (22). Among other pain-related effects, polydatin showed pain-modulatory effects in chronic pelvic pain (23, 24), neuropathic pain (15), and cystitis/bladder pain syndrome (25). However, the precise anti-nociceptive mechanism of polydatin is not revealed.

2. Objectives

The current research aimed to investigate the anti-nociceptive effects of polydatin and the involvement of the L-Arg/NO/cGMP/KATP channel pathway.

3. Methods

3.1. Subjects

Male NMRI mice weighing approximately 25 ± 5 g were purchased from Kermanshah University of Medical Sciences’ animal facility. Animals were housed in standard plastic boxes, with six of them in a group based on the power formula (n = 6). Temperature and humidity were controlled to remain constant at 23 ± 2°C and 50 - 60% relative humidity, respectively. The animals had unrestricted access to food and water, following a consistent 12-hour light/dark cycle. Furthermore, the official animal protection committee approved all protocols at Kermanshah University of Medical Sciences and operated in compliance with the National Institutes of Health Guidelines for the Protection and Use of Lab Animals, Iran (IR.KUMS.AEC.1401.019).

3.2. Drugs

Polydatin (mixed cis and trans), ketorolac (KET), N(gamma)-nitro-l-arginine methyl ester (L-NAME: a NO blocker), sildenafil (a phosphodiesterase inhibitor), and glibenclamide (a KATP channel inhibitor) were all sourced from Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, Missouri, USA. Additionally, L-Arg (a NO precursor) and S-nitroso-N-acetylpenicillamine (SNAP; a NO donor) were obtained from Santa Cruz Biotechnology and Merck, respectively, both companies of the United States. Previous validation has been conducted on the effective doses as well as the methods of medical procedure administration (26-28).

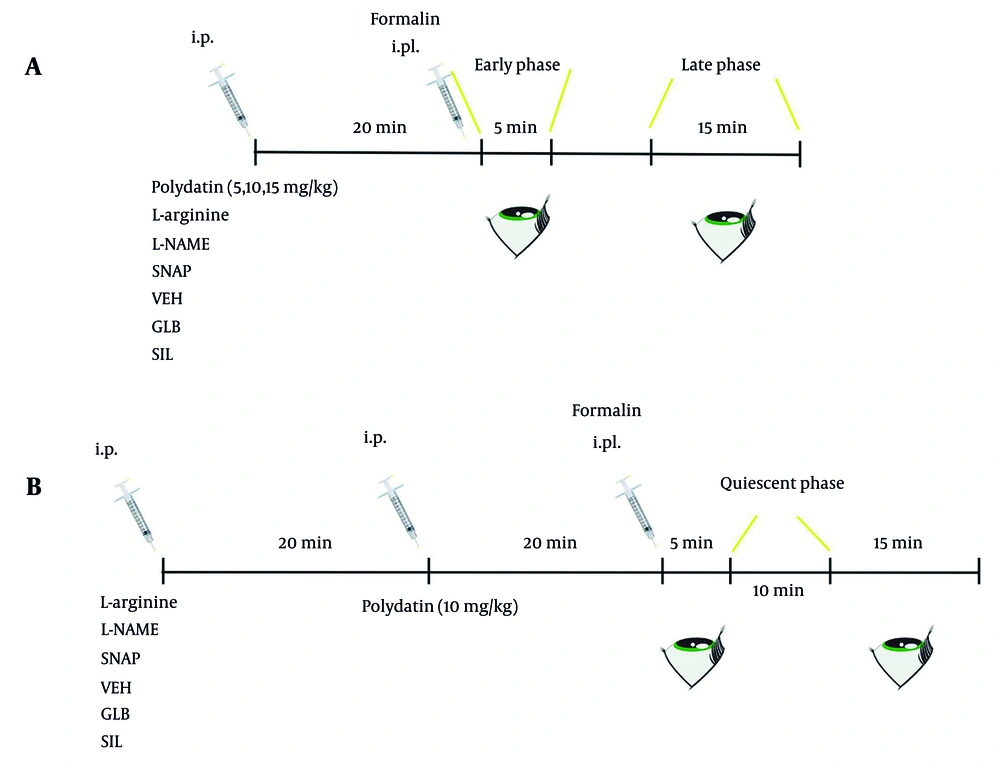

3.3. Formalin Test

To determine the optimal anti-nociceptive dose of polydatin, mice were intraperitoneally (i.p.) administered three different dosages (5, 10, and 15 mg/kg) or other modulatory agents [L-NAME (30 mg/kg), L-Arg (100 mg/kg), SNAP (1 mg/kg), sildenafil (0.5 mg/kg), or glibenclamide (10 mg/kg)]. After 20 minutes, nociception was induced by intraplantar (i.pl.) injection of 25 µL of 2% formaldehyde into the right hind paw. Pain-related behaviors, including paw licking, gnawing, and leaping, were recorded during the first 5 minutes (early phase), which represents acute nociceptor activation, followed by a 10-minute quiescent phase, and then a 15-minute late phase (15 - 30 min) reflecting inflammatory and central sensitization responses. Throughout the experiments, KET (100 mg/kg) was used as the positive control, while saline containing Tween 80 served as the vehicle control (Figure 2A). In a complementary set of experiments, mice were pretreated i.p. with saline + Tween 80 (as a vehicle for all drugs) or pharmacological modulators including L-NAME, L-Arg, SNAP, sildenafil, or glibenclamide. After 20 minutes, the animals received polydatin at the most effective dose identified, followed 20 minutes later by formalin injection. Pain responses were then monitored during the quiescent (0 - 5 min) and late phases (15 - 30 min) to assess the interactions between polydatin and these agents (Figure 2B).

The pain-relieving effects of the individual drugs were also tested separately (5, 29). All experiments were conducted with both observers and data analysts blinded to the treatment conditions (Figure 2).

3.4. Statistical Analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism version 8.0. The data were presented as mean ± SEM. To assess the normality distribution of the data, the Shapiro test was conducted. Statistical differences between groups were determined using one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey's posttest. A significance level of P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

4. Results

4.1. Pain-relieving Impacts of Polydatin

The biphasic timing was a crucial characteristic of formalin-induced pain in mice. The first phase, known as the early or primary phase, occurs throughout the first 5 minutes after a formalin i.p. injection. About 10 minutes after the first phase (which started right after the formalin injection), the second phase of pain began and slowly decreased after 15 minutes. Administering polydatin to mice at 5, 10, or 15 mg/kg greatly reduced their pain in both the early [F (4, 25) = 11.04, P < 0.001, Figure 3A] and late [F (4, 25) = 16.21, P < 0.001, Figure 3B] phases compared to mice that didn’t receive it. The study also showed that 10 mg/kg of polydatin was most effective.

Response of three doses of polydatin [5, 10, 15 mg/kg, intraperitoneally (i.p.)] to formalin-induced pain in male mice during A, primary phase (5 minutes); and B, secondary phase (15 minutes; the data provided is presented as mean ± SEM employing one-way ANOVA and Tukey's test; n = 6; +P < 0.05, ++P < 0.01, +++P < 0.001 vs. control group, *P < 0.05 vs polydatin 10 mg/kg group; abbreviations: PLD, polydatin; KET, ketorolac).

4.2. Impacts of S-nitroso-N-acetylpenicillamine, L-arginine, and N(gamma)-nitro-l-arginine Methyl Ester on the Pain-relieving Characteristics of Polydatin

To find out how polydatin reduces pain, we administered SNAP (1 mg/kg), L-NAME (30 mg/kg), and L-Arg (100 mg/kg) together with it. The SNAP raised NO ratios, thereby enhancing polydatin's pain-relieving impact in both the primary [F (4, 25) = 34.88, P < 0.001, Figure 4A] and secondary [F (4, 25) = 46.86, P < 0.001, Figure 4B] phases of the formalin test in comparison to the control group when administered with polydatin 10 mg/kg. Additionally, SNAP + polydatin 10 mg/kg produced a greater anti-nociceptive effect compared to polydatin 10 mg/kg alone during both the primary and secondary phases (P < 0.05). The L-NAME, in contrast, lowered NO ratios and reduced polydatin's anti-nociceptive impacts. The L-Arg slightly increased the anti-nociceptive effects of polydatin; however, this increase was not statistically significant. The related hypothesis is discussed in the discussion section.

The anti-nociceptive impacts of polydatin (10 mg/kg) in the presence of L-arginine (L-Arg, 100 mg/kg), N(gamma)-nitro-l-arginine methyl ester [L-NAME, 30 mg/kg, nitric oxide (NO) inhibitor], and S-nitroso-N-acetylpenicillamine (SNAP, 1 mg/kg, NO donor) in male mice during A, primary phase (5 minutes); and B, secondary phase (15 minutes) of the formalin test (the data provided is represented as mean ± SEM employing one-way ANOVA and Tukey's test; n = 6; +++P < 0.001 vs. control groups, *P < 0.05, ***P < 0.001 vs. polydatin 10 mg/kg group; abbreviation: PLD, polydatin).

4.3. The Role of S-nitroso-N-acetylpenicillamine, L-arginine, and N(gamma)-nitro-l-arginine Methyl Ester in the Primary and Secondary Stages of the Formalin Test

Neither the primary [F (3, 20) = 2.68, P = 0.074, Figure 5A] nor the secondary phase [F (3, 20) = 0.47, P = 0.706, Figure 5B] stages of mice pain thresholds were significantly altered by i.p. administration of SNAP, L-arginine, or L-NAME when administered alone without polydatin. This lack of effect when administered individually supports the hypothesis of a synergistic interaction with polydatin, suggesting that these agents potentiate polydatin’s antinociceptive activity only in combination.

The anti-nociceptive impacts of L-arginine [L-Arg, 100 mg/kg, intraperitoneally (i.p.)], N(gamma)-nitro-l-arginine methyl ester [L-NAME, 30 mg/kg, i.p., nitric oxide (NO) inhibitor];, and S-nitroso-N-acetylpenicillamine (SNAP, 1 mg/kg, i.p., NO donor) in both phases of the formalin test in male mice during A, primary phase (5 minutes); and B, secondary phases (15 minutes; the data provided is represented as mean ± SEM employing one-way ANOVA and Tukey's test; n = 6).

4.4. The Role of Sildenafil and Glibenclamide on the Pain-relieving Impact of Polydatin

The probable anti-nociceptive impact of polydatin is further diminished since glibenclamide inhibits the KATP channel. In both stages of the formalin test, we found that polydatin's anti-nociceptive impacts were significantly reduced when administered with glibenclamide (10 mg/kg) compared to polydatin 10 mg/kg alone in the primary phase (P < 0.001). On the other hand, pre-treatment with sildenafil (0.5 mg/kg) and polydatin (10 mg/kg) increased the anti-nociceptive effect of polydatin (10 mg/kg) in the secondary phase (P < 0.05) by increasing cGMP levels. A single administration of sildenafil (0.5 mg/kg) or glibenclamide (10 mg/kg) alone did not produce a meaningful anti-nociceptive impact in the primary [F (5, 30) = 25.32, P < 0.001, Figure 6A], and the secondary [F (5, 30) = 45.37, P < 0.001, Figure 6B] phases of the formalin test, highlighting the key role of polydatin in producing the observed anti-nociceptive effects.

The anti-nociceptive impacts of sildenafil [0.5 mg/kg, intraperitoneally (i.p.)] and glibenclamide (10 mg/kg, i.p.) in both phases of the formalin test in the presence and absence of polydatin (10 mg/kg, i.p.) in male mice during A, primary phase (5 minutes); and B, secondary phase (15 minutes; the data provided is represented as mean ± SEM employing one-way ANOVA and Tukey's test; n = 6; ++P < 0.01, +++P < 0.001 vs. control groups, *P < 0.05, ***P < 0.001 vs. polydatin 10 mg/kg group; abbreviations: PLD, polydatin; SIL, sildenafil; GLB, glibenclamide).

5. Discussion

Our research showed that the pain-relieving effect of a dose of 10 mg/kg polydatin is mediated by the NO/cGMP/KATP channel signaling pathway in both phases of nociceptive pain evaluated by the formalin test (Figure 7). The results indicated a U-shaped dose-nociception (inverted U-shaped dose-anti-nociceptive effect) response of polydatin. A U-shaped curve in pharmacodynamics, as related to hormesis, implies that the effect of a substance varies with dose in a biphasic manner: Low doses stimulate a beneficial or stimulatory effect, while high doses produce an inhibitory, toxic, or adverse effect, with an optimal intermediate dose producing the best response. This non-linear dose-response relationship means both too little and too much of a substance can be ineffective or harmful, while a moderate dose is optimal (30). Accordingly, the dose of 10 mg/kg of polydatin showed more promising anti-nociceptive effects in mice. From a mechanistic point of view, we showed that the anti-nociceptive effects of polydatin are mediated by the NO/cGMP/KATP pathway.

Pain is a multifaceted sensation that can greatly affect one's quality of life. It can stem from different causes such as tissue damage, inflammation, and neuropathy. Effectively managing pain has always been a persistent challenge for healthcare providers. Consequently, there is an ongoing demand for reliable and secure pain-relieving medications (31). Polydatin is a naturally occurring compound found in various plants, such as Polygonum cuspidatum and grapes. It is a potent stilbenoid polyphenol and a resveratrol derivative with improved bioavailability (13). Previous studies did not provide a comprehensive understanding of the mechanisms involved in the anti-nociceptive effects triggered by polydatin. The findings from our study indicate that the pain experienced during both phases of the formalin test is diminished following the administration of various doses of polydatin. From a mechanistic point of view, the L-Arg/NO/cGMP/KATP channel signaling pathway is a complex molecular cascade involved in pain perception. This pathway starts with the conversion of L-Arg into NO by the enzyme NOS (32). In this regard, our results showed that pretreatment of mice with L-NAME as a NO blocker inhibited the analgesic effects of polydatin, while pretreatment with SNAP as a NO donor was associated, but not meaningfully, with increasing the anti-nociceptive effects of polydatin. Our study also indicated that pretreatment with L-Arg could not meaningfully decrease nociception. However, no significant concerns have been raised about the limited penetration of L-Arg into the brain, and the expected pharmacological effects have been consistently reported using this compound (26-28). The role of L-Arg in nociception is complex and context-dependent. Some studies show L-Arg can exert both anti-nociceptive and nociceptive effects via different pathways in the brain. It may reduce pain through the kyotorphin-Met-enkephalin opioid pathway but also facilitate nociception via NO and cGMP signaling pathways (33). This procedure on the non-responsiveness of L-Arg and SNAP on the nociceptive effect of polydatin could also be due to the dual role of NO in pain transmission and control (7); in low doses, it could help the anti-nociceptive responses, while higher doses may facilitate nociception. Inhibitory effects of polydatin on higher doses and pathogenesis dosage of NO have also been shown in RAW 264.7 cells (34). According to this L-Arg/NO/cGMP/KATP channel mechanism, in our study, glibenclamide as a KATP channel inhibitor hindered the analgesic effects of polydatin. During another in vivo report, the potential of polydatin in the opening of KATP channels was presented by Miao et al. (35). Glibenclamide, a sulfonylurea, blocks KATP channels by binding to their sulfonylurea receptor, preventing their opening and thus increasing neuronal excitability (36, 37). In the formalin test, which consists of neurogenic and inflammatory pain phases, KATP channel activation helps inhibit nociceptive signaling. When glibenclamide attenuates analgesic effects in this test, it indicates that KATP channels are actively mediating anti-nociception, suggesting their role in both peripheral and central pain processes. This blockade reinforces the idea that KATP channels serve as endogenous regulators of pain transmission, further supported by other studies showing that KATP channel openers reduce pain responses. A study showed that glibenclamide attenuated trigeminal pain transmission in rats, indicating its role in KATP channel-mediated pain modulation. It also discusses the effects of glibenclamide on hypersensitivity induced by migraine triggers and highlights KATP channel subtype specificity in pain (38). Another study on the anti-nociceptive effect of pregabalin in the formalin test shows glibenclamide’s inhibitory impact on analgesia, supporting the role of KATP channels in regulating peripheral neuronal excitability and neurotransmitter release in spinal pain pathways (39).

In a more recent study, polydatin attenuated neuroinflammation but not mechanical hypersensitivity in mice (21). Confirming the analgesic effect of polydatin, Guan et al. reported that polydatin can inhibit the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines and chemokines as well as the activation of inflammatory pathways such as NF-κB. By reducing inflammation, polydatin could help in reducing pain. They also emphasized that polydatin may affect the release and activity of neurotransmitters involved in pain signaling, such as serotonin and glutamate, potentially altering pain perception and providing analgesic effects (21). Another research trial demonstrated that when polydatin is combined with palmitoylethanolamide, an endogenous fatty acid amide known for its anti-inflammatory properties, it could effectively reduce pain in women suffering from chronic pelvic pain and improve their overall quality of life (23). Polydatin normalized mitochondrial superoxides, improved neurite outgrowth, and facilitated Nrf2-directed antioxidant signaling. It also alleviated oxidative damage and elevated mitochondrial biogenesis in experimental diabetic neuropathy (40). Xu et al. also found that polydatin attenuated spinal cord injury in rats, and its effects are associated with the activation of astrocytic mu-opioid receptors, which cause conditioned place preference (41).

5.1. Conclusions

Polydatin exhibits potential as a candidate for pain relief due to its ability to regulate the NO/cGMP/KATP channel signaling pathway. By enhancing NO production, elevating intracellular cGMP levels, and promoting KATP channel activation, polydatin significantly reduced nociceptive behaviors in the formalin test. These findings highlight the involvement of specific molecular components — NO, cGMP, and KATP channels — in mediating its anti-nociceptive effects. Further studies are warranted to fully elucidate these mechanisms and to assess the therapeutic potential of polydatin in pain management.

5.2. Limitations

Several limitations of this study should be considered when interpreting the findings. First, the experiments were conducted exclusively in male NMRI mice, which may limit the generalizability of the results to other sexes, particularly females. Second, only the intraperitoneal route of administration for polydatin and related compounds was evaluated, and the effects of alternative administration routes as well as pharmacokinetic data were not assessed. Third, the study focused solely on pharmacological modulation of the L-Arg/NO/cGMP/KATP channel pathway without direct molecular or biochemical measurements, such as NO levels, cGMP concentrations, or KATP channel activity, which could have provided stronger mechanistic evidence.

5.3. Future Studies

Future studies could benefit from distinguishing the roles of central versus peripheral NO involvement using more specific molecular assays. Incorporating such assessments would clarify the precise mechanisms by which polydatin exerts its effects and could guide optimization of its therapeutic potential.

![Response of three doses of polydatin [5, 10, 15 mg/kg, intraperitoneally (i.p.)] to formalin-induced pain in male mice during A, primary phase (5 minutes); and B, secondary phase (15 minutes; the data provided is presented as mean ± SEM employing one-way ANOVA and Tukey's test; n = 6; +P < 0.05, ++P < 0.01, +++P < 0.001 vs. control group, *P < 0.05 vs polydatin 10 mg/kg group; abbreviations: PLD, polydatin; KET, ketorolac). Response of three doses of polydatin [5, 10, 15 mg/kg, intraperitoneally (i.p.)] to formalin-induced pain in male mice during A, primary phase (5 minutes); and B, secondary phase (15 minutes; the data provided is presented as mean ± SEM employing one-way ANOVA and Tukey's test; n = 6; +P < 0.05, ++P < 0.01, +++P < 0.001 vs. control group, *P < 0.05 vs polydatin 10 mg/kg group; abbreviations: PLD, polydatin; KET, ketorolac).](https://services.brieflands.com/cdn/serve/3170d/d60ebb6a3a56a24bf8f05b3839e68291f975cf42/jjnpp-20-4-163665-i003-preview.webp)

![The anti-nociceptive impacts of polydatin (10 mg/kg) in the presence of L-arginine (L-Arg, 100 mg/kg), N(gamma)-nitro-l-arginine methyl ester [L-NAME, 30 mg/kg, nitric oxide (NO) inhibitor], and S-nitroso-N-acetylpenicillamine (SNAP, 1 mg/kg, NO donor) in male mice during A, primary phase (5 minutes); and B, secondary phase (15 minutes) of the formalin test (the data provided is represented as mean ± SEM employing one-way ANOVA and Tukey's test; n = 6; +++P < 0.001 vs. control groups, *P < 0.05, ***P < 0.001 vs. polydatin 10 mg/kg group; abbreviation: PLD, polydatin). The anti-nociceptive impacts of polydatin (10 mg/kg) in the presence of L-arginine (L-Arg, 100 mg/kg), N(gamma)-nitro-l-arginine methyl ester [L-NAME, 30 mg/kg, nitric oxide (NO) inhibitor], and S-nitroso-N-acetylpenicillamine (SNAP, 1 mg/kg, NO donor) in male mice during A, primary phase (5 minutes); and B, secondary phase (15 minutes) of the formalin test (the data provided is represented as mean ± SEM employing one-way ANOVA and Tukey's test; n = 6; +++P < 0.001 vs. control groups, *P < 0.05, ***P < 0.001 vs. polydatin 10 mg/kg group; abbreviation: PLD, polydatin).](https://services.brieflands.com/cdn/serve/3170d/38b7ea188dc3dd85debe161b4cdd2899aa932cb0/jjnpp-20-4-163665-i004-preview.webp)

![The anti-nociceptive impacts of L-arginine [L-Arg, 100 mg/kg, intraperitoneally (i.p.)], N(gamma)-nitro-l-arginine methyl ester [L-NAME, 30 mg/kg, i.p., nitric oxide (NO) inhibitor];, and S-nitroso-N-acetylpenicillamine (SNAP, 1 mg/kg, i.p., NO donor) in both phases of the formalin test in male mice during A, primary phase (5 minutes); and B, secondary phases (15 minutes; the data provided is represented as mean ± SEM employing one-way ANOVA and Tukey's test; n = 6). The anti-nociceptive impacts of L-arginine [L-Arg, 100 mg/kg, intraperitoneally (i.p.)], N(gamma)-nitro-l-arginine methyl ester [L-NAME, 30 mg/kg, i.p., nitric oxide (NO) inhibitor];, and S-nitroso-N-acetylpenicillamine (SNAP, 1 mg/kg, i.p., NO donor) in both phases of the formalin test in male mice during A, primary phase (5 minutes); and B, secondary phases (15 minutes; the data provided is represented as mean ± SEM employing one-way ANOVA and Tukey's test; n = 6).](https://services.brieflands.com/cdn/serve/3170d/7cabfecce90a8c52483971deb04494c4cef0aea4/jjnpp-20-4-163665-i005-preview.webp)

![The anti-nociceptive impacts of sildenafil [0.5 mg/kg, intraperitoneally (i.p.)] and glibenclamide (10 mg/kg, i.p.) in both phases of the formalin test in the presence and absence of polydatin (10 mg/kg, i.p.) in male mice during A, primary phase (5 minutes); and B, secondary phase (15 minutes; the data provided is represented as mean ± SEM employing one-way ANOVA and Tukey's test; n = 6; ++P < 0.01, +++P < 0.001 vs. control groups, *P < 0.05, ***P < 0.001 vs. polydatin 10 mg/kg group; abbreviations: PLD, polydatin; SIL, sildenafil; GLB, glibenclamide). The anti-nociceptive impacts of sildenafil [0.5 mg/kg, intraperitoneally (i.p.)] and glibenclamide (10 mg/kg, i.p.) in both phases of the formalin test in the presence and absence of polydatin (10 mg/kg, i.p.) in male mice during A, primary phase (5 minutes); and B, secondary phase (15 minutes; the data provided is represented as mean ± SEM employing one-way ANOVA and Tukey's test; n = 6; ++P < 0.01, +++P < 0.001 vs. control groups, *P < 0.05, ***P < 0.001 vs. polydatin 10 mg/kg group; abbreviations: PLD, polydatin; SIL, sildenafil; GLB, glibenclamide).](https://services.brieflands.com/cdn/serve/3170d/f28bfbf6c4948fac0d6f6a647ce29a9950a6483a/jjnpp-20-4-163665-i006-preview.webp)