1. Background

Diabetes represents a rapidly escalating global health concern. In 2021, the World Health Organization (WHO) reported that around 537 million adults were affected by the disease worldwide. By 2030, 643 million people were estimated to have diabetes, with predicted increases to 783 million in 2045 (1).

2. Objectives

Saurauia bracteosa is an endemic plant in North Sumatra, Indonesia, and has been traditionally used as an antidiabetic remedy by the Batak Toba and Karo people and may have the potential to manage diabetes (2, 3). Scientific research regarding the antidiabetic activity of S. bracteosa leaves is still very limited. So far, research has mostly focused on the Saurauia vulcani species (4-6). These two species are similar but differ in the area where they grow, leaf morphology, and flower morphology (3). Therefore, the objective of this research was to characterize the secondary metabolites in S. bracteosa leaf extract and assess its antidiabetic potential using an in vivo experimental model.

3. Methods

3.1. Materials

Analytical grade ethanol (Smartlab, Indonesia), carboxymethylcellulose sodium (CMC-Na) (Merck, Germany), ELISA kit HbA1c (ABclonal, USA), cholesterol and triglyceride reagent (Sanymed, Italy), fructose (Fructosan Omnia, Turkey), glucose transporter 4 (GLUT4) monoclonal antibody (Bioworld, China), metformin (PT. Hexpharm, Indonesia), streptozotocin (STZ) (Chemcruz, USA).

3.2. Saurauia bracteosa Leaves Collection and Determination

Leaves of S. bracteosa were collected from North Tapanuli, North Sumatra, Indonesia, and authenticated at the Herbarium Bogoriense, National Research and Innovation Agency (BRIN). A voucher specimen was deposited under the reference number issued on April 8, 2022 (B-964/IV/DI.05.07/4/2022).

3.3. Extraction

Fresh leaves (6.5 kg) were cleaned, dried at 40 °C, and pulverized. Extraction was conducted by maceration with ethanol, following the Indonesian Herbal Pharmacopoeia guidelines (162.84 g) (7). Crude extract was concentrated by rotary evaporation (40 °C). The dried extract was reconstituted in 0.5% carboxymethylcellulose sodium (CMC-Na) solution for oral administration, with no ethanol remaining.

3.4. Identification and Characterization of the Chemical Compounds of Saurauia bracteosa Leaf Extract Through Liquid Chromatography-High Resolution Mass Spectrometry

Phytochemical profiling was carried out using a Thermo Scientific Vanquish UHPLC system coupled to an Orbitrap high-resolution mass spectrometer. Separation was achieved on a Phenyl-Hexyl column (100 × 2.1 mm, 2.6 µm) at 40 °C with a mobile phase consisting of water and methanol (both containing 0.1% formic acid) under a gradient elution at 0.3 mL/min. Samples (3 µL) were analyzed in positive ESI mode across m/z 66.7–1000. Data acquisition was performed in full-MS ddMS2 mode. Compound identification was conducted using Compound Discoverer™ with database matching (mzCloud, ChemSpider). Full instrument parameters, gradient conditions, and data-processing settings are provided in Appendix 1, in the Supplementary File.

3.5. Antidiabetic Activity Test

Male Wistar albino rats (Rattus novergicus) aged 6 - 8 weeks were acquired and housed in the Pharmacology Laboratory at the Faculty of Pharmacy, Universitas Sumatera Utara, Medan, Indonesia. The minimum number of rats was determined using Federer’s formula: (T-1)(N-1) ≥ 15, where T is the number of groups and N is the number of animals per group. All experimental procedures involving animals were performed in compliance with institutional ethical standards and received approval from the Animal Research Ethics Committee of Universitas Sumatera Utara (Protocol No. 0701/KEPH-FMIPA/2022).

After acclimatization, an obesity rat model was created by administering a high-fat diet and fructose for four weeks, based on a previous method with several modifications (8-12). Rats were fed 2 mL of 20% fructose solution and 2 mL of a high-fat diet composed of quail egg yolk, beef tallow, and chicken fat (40:20:40). Following four weeks of treatment, the rats in the experimental group received a single intraperitoneal dose of streptozotocin (STZ) at 25 mg/kg body weight. Fasting blood glucose was measured 72 hours after induction, and rats with readings ≥ 300 mg/dL were considered diabetic and included in the test group (10).

Diabetic rats were randomly assigned to five groups (n = 4 per group): (I) negative control (CMC-Na vehicle), (II - IV) treatment groups receiving the extract at 100, 200, and 400 mg/kg, respectively, (V) positive control (metformin 40 mg/kg), and one normal control group. Treatments were administered once daily for four weeks, and blood glucose levels were measured weekly. Dose selection was guided by traditional use, human-to-animal dose conversion, and previous research with modification (4, 13). All rats underwent an overnight fasting period at the termination of the experimental protocol, and their fasting blood glucose levels were measured using a glucometer (Easytouch GCU, Taiwan). Surgical incisions were made in the chest cavity, and blood samples were collected via cardiac puncture and centrifuged at 3,000 rpm for 10 min to isolate the serum. This serum was used to measure total cholesterol and triglycerides. The erythrocyte fraction was processed to prepare erythrocyte lysates (hemolysates), which were used for hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c). Pancreatic and gastrocnemius muscle tissues were harvested for histological and immunohistochemical analysis.

3.6. Hemoglobin A1c

Hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) in erythrocyte lysates was measured using a sandwich ELISA, which outputs mass concentration (µg/mL). HbA1c levels were quantified using 2 µL of erythrocyte lysate (hemolysate prepared from whole blood) serum, diluted 1:10,000 prior to analysis. A standard calibration curve (3.125 - 200 ng/mL) was prepared. After plate washing, 100 µL of standards, diluent (blank), or samples were added to antibody-coated wells and incubated at 37 °C for 2 h. The wells were washed and incubated with biotin-labeled antibody (1 h), washed again, and then treated with streptavidin-HRP (30 min). Following three washes, 90 µL of TMB substrate was added and incubated for 15 min in the dark. Absorbance was measured at 450 nm using a microplate spectrophotometer, and HbA1c concentrations were calculated from the calibration curve. Complete procedure presented in Appendix 2, in the Supplementary File.

3.7. Microscopic Evaluation of Pancreas

Pancreatic tissue was rinsed with 0.9% NaCl and fixed in 10% neutral buffered formalin for 48 h. Samples were processed through graded ethanol, cleared with toluene, and embedded in paraffin. Sections (5 - 6 µm) were cut using a rotary microtome, mounted on gelatin-coated slides, and stained with hematoxylin–eosin using standard procedures. Only sections containing ≥ 10 islets of Langerhans were included for analysis. Islet diameters were measured under a bright-field microscope at 400× magnification (14, 15). Complete procedure presented in Appendix 3, in the Supplementary File.

3.8. Glucose Transporter 4 Expression Using Immunohistochemistry

Immunohistochemical testing was performed according to general immunohistochemical testing procedures (16) using Leica Biosystems. Skeletal muscle tissue was obtained from the gastrocnemius muscle, paraffin-embedded, and sectioned at a thickness of 4 µm using a microtome. Each paraffin block was recut once for antibody staining. Sections were incubated with a GLUT4 monoclonal antibody for 30 min at room temperature. After washing with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) (pH 7.4), sections were treated with the Dako REAL EnVision Detection System and incubated for 30 min. Slides were washed in PBS-Tween 20, developed with 3,3'-diaminobenzidine (DAB) for 2 - 5 min, and rinsed in running water. Counterstaining was performed with hematoxylin, followed by rehydration through graded ethanol (70 - 100%) and clearing in xylene. Finally, sections were mounted with a coverslip. Complete procedure presented in Appendix 4, in the Supplementary File.

3.9. Lipid Profile

Total cholesterol and triglyceride concentrations were quantified using enzymatic colorimetric assay kits following the manufacturer’s protocols. For each analysis, blank, standard, and serum sample tubes were prepared and combined with the respective enzymatic reagent. The mixtures were gently homogenized and incubated at 37 °C for 5 minutes to facilitate the development of the chromogenic reaction. Absorbance values were subsequently measured at 510 nm using a semi-automatic spectrophotometer (Sanymed SM 105, China). Analyte concentrations were calculated by comparing the sample absorbance with the corresponding standard curve, and the results were expressed in milligrams per deciliter (mg/dL).

3.10. Statistical Analysis

Data are presented as mean ± SEM. Blood glucose levels were analyzed using two-way repeated-measures analysis of variance (ANOVA), followed by Tukey’s post hoc test. Other parameters were analyzed using one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey's post hoc test. All analyses were conducted in GraphPad Prism 9.5.1 (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA, USA), with statistical significance defined as P < 0.05.

4. Results

4.1. Liquid Chromatography-High Resolution Mass Spectrometry Analysis

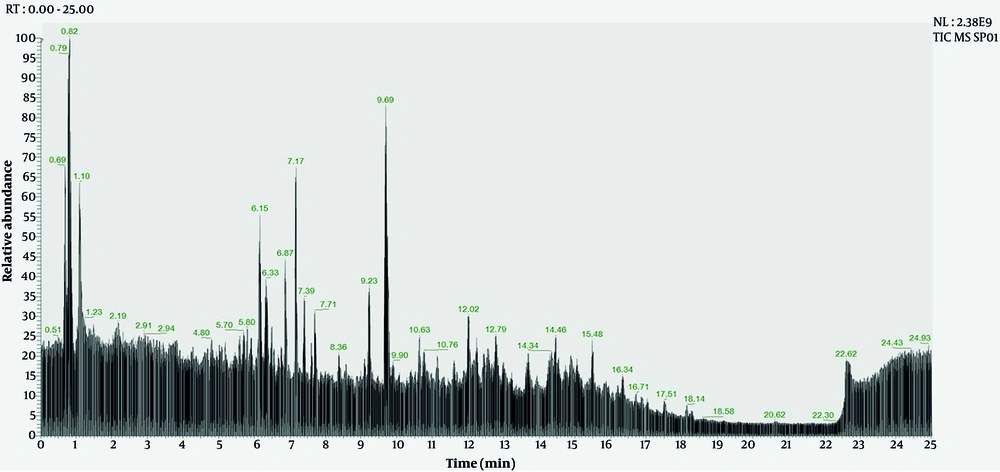

Liquid chromatography-high resolution mass spectrometry (LC-HR MS) analysis of the ethanol extract of S. bracteosa leaves can be seen in Figure 1 and Table 1.

| Chemical Compound | Molecular Formula | Calculation of Molecular Weight (g/mol) | Retention Time (Minute) | Peak Area (a.u.) | mzCloud Match (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Apigenin | C15H10O5 | 270.05 | 8.40 | 8398448 | 99.90 |

| Juglalin | C20H18O10 | 418.08 | 6.50 | 241284938 | 99.80 |

| Hyperoside | C21H20O12 | 464.09 | 5.80 | 380609359 | 99.70 |

| Afzelin | C21H20O10 | 432.10 | 6.80 | 93602489 | 99.60 |

| Rutin | C27H30O16 | 610.15 | 5.50 | 483639107 | 99.40 |

| Quercetin-3β-D-glucoside | C21H20O12 | 464.09 | 5.30 | 8871389 | 99.40 |

| Quercitrin | C21H20O11 | 448.10 | 6.30 | 554335923 | 99.40 |

| Kaempferol | C15 H10 O6 | 286.04 | 6.80 | 97288023 | 99.30 |

| Isorhamnetin | C16H12O7 | 316.05 | 6.80 | 16372888 | 98.70 |

| Quercetin | C15H10O7 | 302.04 | 6.30 | 122542637 | 98.50 |

| Diosmetin | C16H12O6 | 300.06 | 8.60 | 49713691 | 98.30 |

| Myricetin 3-O-β-D-galactopyranoside | C21H20O13 | 480.09 | 5.10 | 12581708 | 98.10 |

| Naringenin | C15H12O5 | 272.06 | 8.50 | 7656500 | 97.50 |

| DL-stachydrine | C7H13NO2 | 143.09 | 0.80 | 178466310 | 97.10 |

| Glycitein | C16H12O5 | 284.06 | 10.10 | 86200166 | 96.80 |

| Ursolic acid | C30H48O3 | 456.359 | 14.50 | 425388217 | 95.60 |

| (4S)-4-hydroxy-3,5,5-trimethyl-4-[(1E)-3-{[(2R,3R,4S,5S,6R)-3,4,5-trihydroxy-6-(hydroxymethyl)oxan-2-yl]oxy}but-1-en-1-yl]cyclohex-2-en-1-one | C19H30O8 | 386.19 | 4.60 | 94886103 | 95.50 |

| 4-O-feruloyl-D-quinic acid | C17H20O9 | 368.11 | 5.10 | 26601977 | 95.00 |

| Pyrogallol | C6H6O3 | 126.03 | 1.50 | 61849367 | 93.90 |

| Oleanolic acid | C30H48O3 | 456.35 | 14.70 | 306845829 | 93.30 |

| Prunin | C21H22O10 | 434.12 | 6.40 | 5477636 | 93.30 |

| p-Coumaric acid | C9H8O3 | 164.04 | 14.30 | 35599183 | 92.50 |

Abbreviation: mz, mass-to-charge ratio; a.u, arbitrary units.

Based on Figure 1 and Table 1, LC-HR MS analysis of the ethanol extract of S. bracteosa leaves identified 22 compounds with similarity above 90%. Several flavonoids and phenolic compounds are detected, with high mzCloud match percentages (mostly above 95%), indicating a high degree of confidence in compound identification. Rutin, quercitrin, and hyperoside had the highest peak areas, suggesting a relatively higher abundance in the analyzed sample. The retention times of the compounds range from as low as 0.80 minutes (DL-stachydrine) to as high as 14.70 minutes (oleanolic acid), reflecting differences in polarity and interaction with the chromatographic column. The molecular weights range widely from small phenolics such as pyrogallol (126.03 g/mol) to complex triterpenoids such as ursolic acid and oleanolic acid (456.35 - 456.36 g/mol).

4.2. Effect of Saurauia bracteosa Extract on Blood Glucose Profile

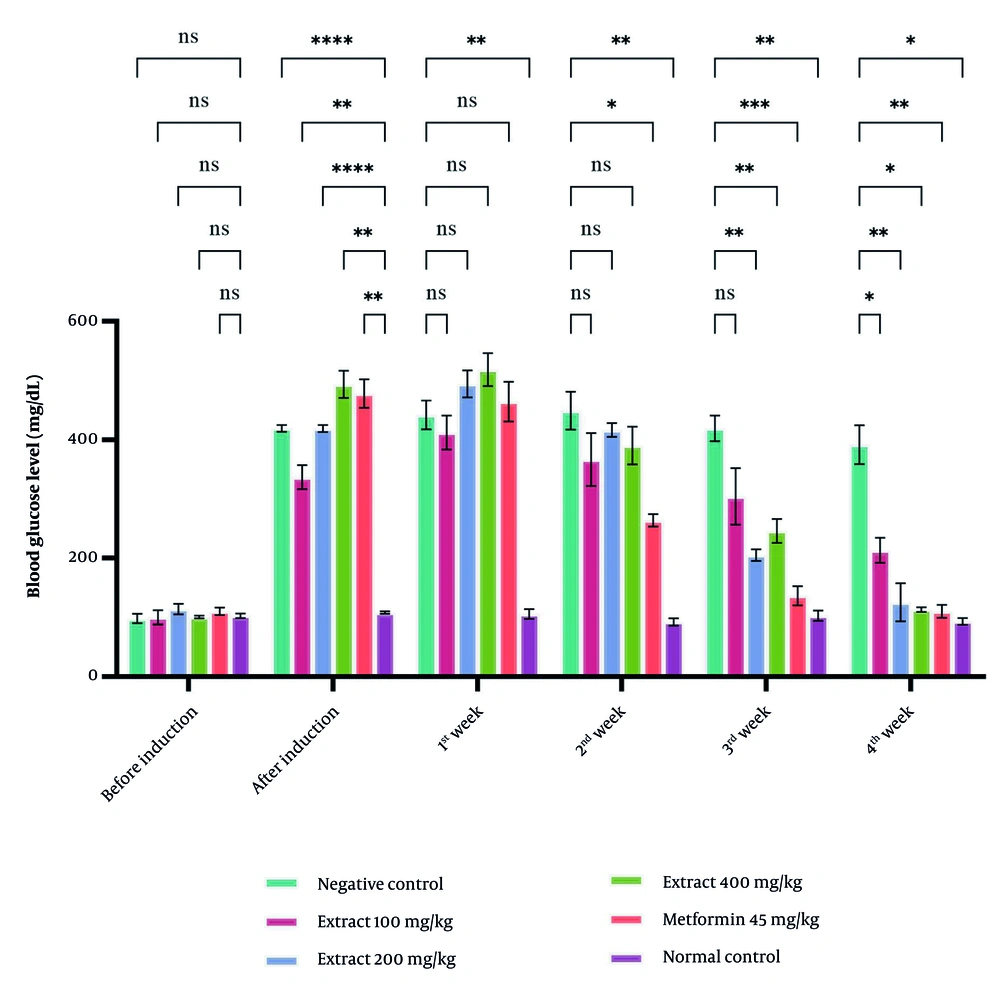

Blood glucose levels increased to more than 300 mg/dL after induction, confirming successful diabetes modelling. During the first two weeks, the extract did not produce a significant reduction, whereas metformin (45 mg/kg) showed a noticeable glucose-lowering effect. By week three, extract doses of 100, 200, and 400 mg/kg significantly reduced blood glucose compared with the negative control (P < 0.05), with the most significant effect at 400 mg/kg. The three extract doses demonstrated similar efficacy, with no significant differences among them (Figure 2).

Effect of Saurauia bracteosa extract administration on blood glucose levels of rats during 4 weeks of treatment. For each group, the data are presented as mean ± standard error of the mean of four replicates. (Abbreviation: Ns, not significant; *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001; ****P < 0.0001)

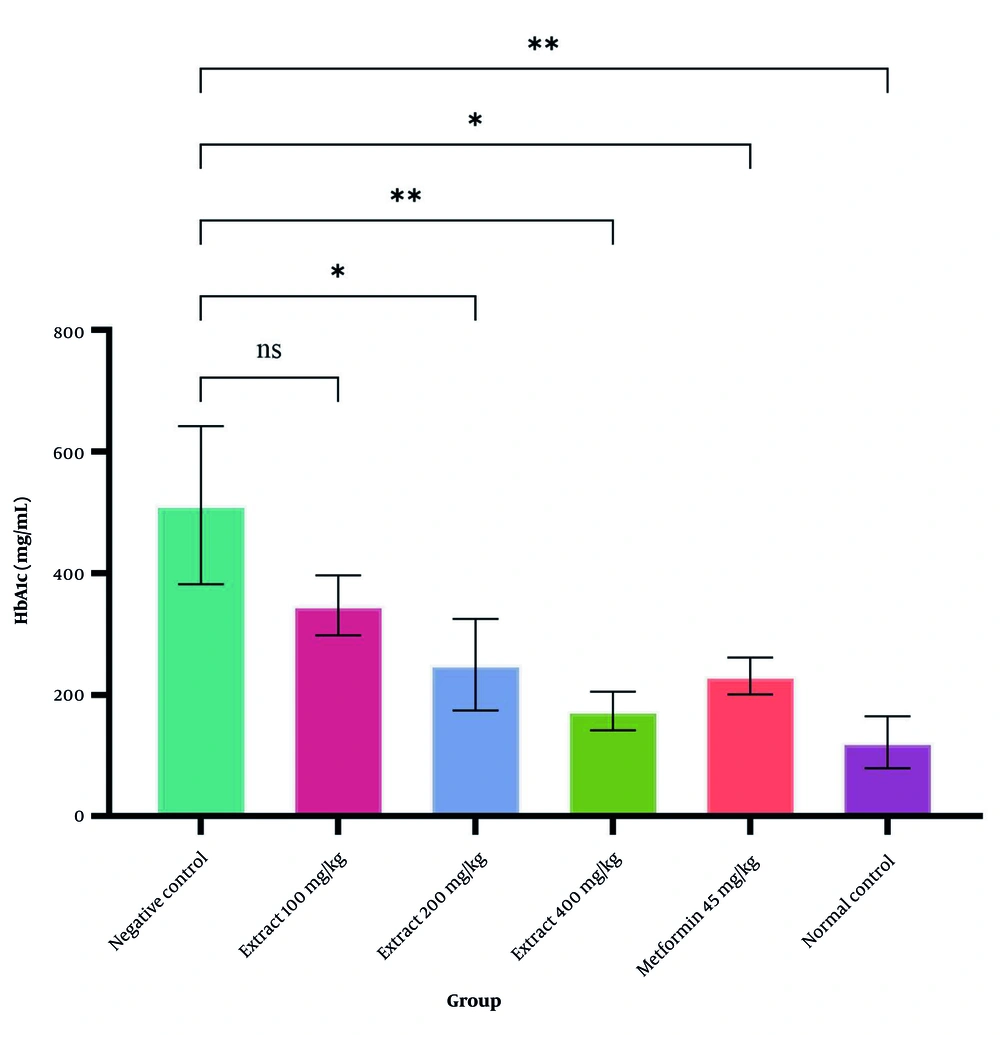

4.3. Hemoglobin A1c

Figure 3 presents the significant differences in HbA1c levels between the negative and normal control groups. Treatment with S. bracteosa extract at doses of 200 and 400 mg/kg, along with 45 mg/kg of metformin, led to a significant decline in serum HbA1c levels compared with the untreated diabetic group (P < 0.05). The greatest reduction was observed in the group receiving a 400 mg/kg dose of S. bracteosa extract.

4.4. The Islets of Langerhans

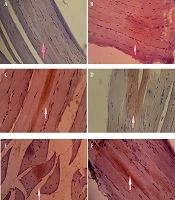

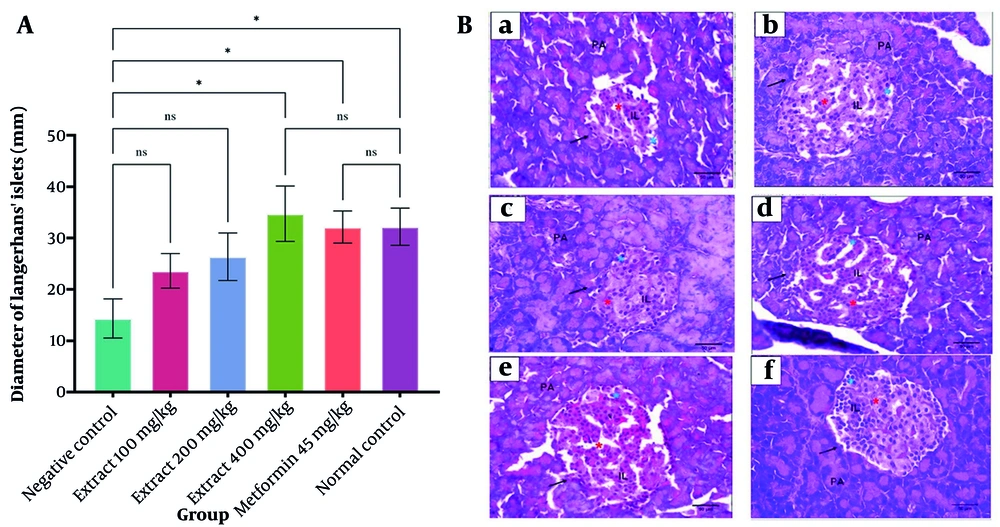

The S. bracteosa extract increased the average diameter of the islets of Langerhans, with the 400 mg/kg dose showing a significant improvement compared with the negative control (P < 0.05). Both the high-dose extract and metformin restored islet morphology to a condition comparable to the normal group. Normal pancreatic tissue displayed well-organised acinar cells and intact islets with peripheral α-cells and centrally located β-cells. In contrast, the negative control exhibited β-cell degeneration and a reduction in islet size. The 400 mg/kg extract produced the most notable improvement, as reflected by a larger islet area, higher cell density, and signs of cellular recovery similar to those observed with metformin (Figure 4 and Table 2).

A, effect of Saurauia bracteosa extract on the diameter of Langerhans’ islets. For each group, the data are presented as mean ± standard error of the mean of ten replicates; B, effect of Saurauia bracteosa extract on the diameter of Langerhans islets at magnification 40 × 10; a, negative control, b, extract dose of 100 mg/kg; c, extract dose of 200 mg/kg; d, extract dose of 400 mg/kg; e, positive control (metformin 45 mg/kg); and f, normal control. (Abbreviation: Ns, not significant; PA, pancreatic acinar; IL, islet of Langerhans (blue star (alpha cells); red star (beta cells); black arrow (cell membrane), *P < 0.05)

a Data represent the mean of 10 islets of Langerhans.

b P < 0.05: Significantly different from the normal control group.

c P < 0.05: Significantly different from the positive control group.

d P < 0.05: Significantly different from the negative control group.

4.5. Glucose Transporter 4 Expression in Skeletal Muscle Cells

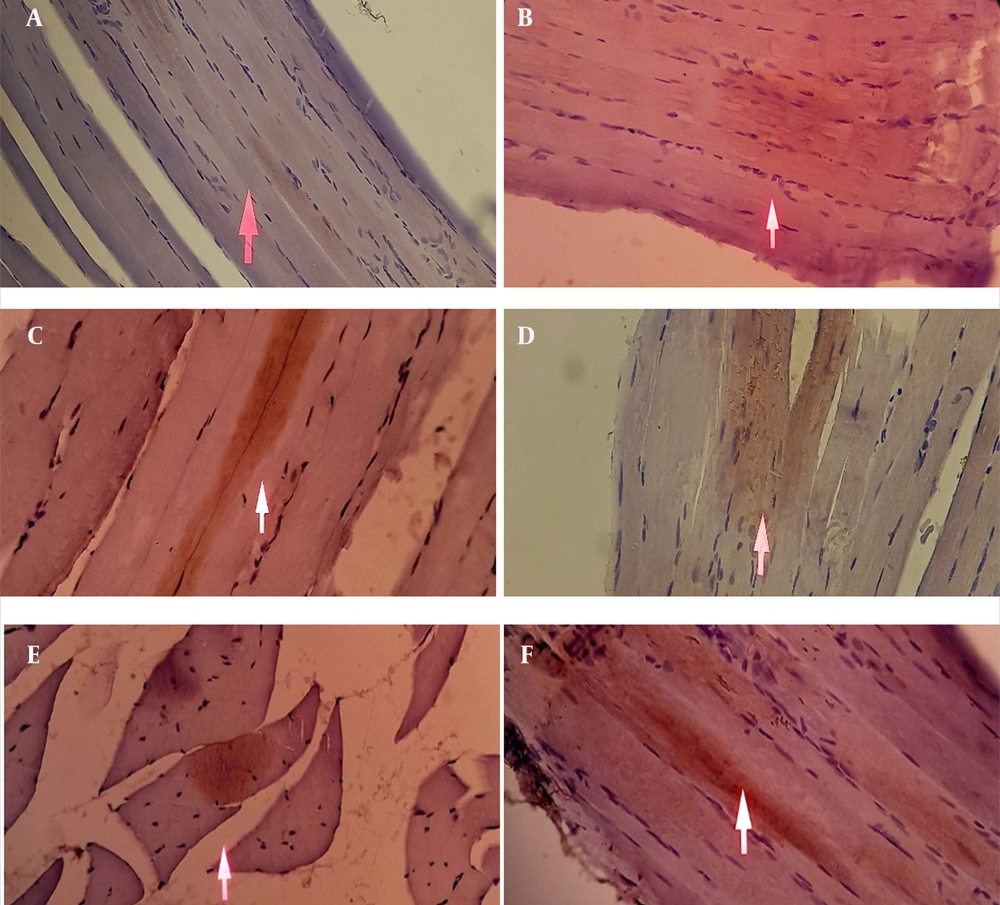

As shown in Figure 5 and Table 3, immunohistochemical analysis revealed minimal GLUT4 expression in the skeletal muscle tissue of the negative control group. In contrast, rats treated with S. bracteosa extract at doses of 100, 200, and 400 mg/kg as well as metformin (45 mg/kg) and the normal control group showed increased GLUT4 expression compared with the negative control. The brown immunostaining, indicative of GLUT4 presence, appeared more intense in treated groups. However, the distribution was diffuse throughout the cytoplasm of muscle fibers and not strictly confined to the plasma membrane. These findings suggest an upregulation of GLUT4 protein abundance, which may contribute to improved glucose utilization, although definitive evidence of membrane translocation was not obtained in this study.

Effect of Saurauia bracteosa extract on glucose transporter 4 (GLUT4) expression in skeletal muscle cells by immunohistochemical study. The white arrow shows GLUT4 expression in the skeletal muscle cells. A, negative control; B, extract dose of 100 mg/kg; C, extract dose of 200 mg/kg; D, extract dose of 400 mg/kg; E, positive control (metformin 45 mg/kg); F, normal control.

| Experimental Group | Cell Distribution Score ± SD b | Staining Intensity Score ± SD c | Total IRS (Distribution x Intensity) ± SD d |

| Negative control | 1.00 ± 0.00 | 1.00 ± 0.00 | 1.00 ± 0.00 |

| Extract 100 mg/kg | 1.00 ± 0.00 | 1.00 ± 0.00 | 1.00 ± 0.00 |

| Extract 200 mg/kg | 1.0 ± 0.00 | 2.00 ± 0.00 | 2.00 ± 0.00 |

| Extract 400 mg/kg | 1.00 ± 0.00 | 2.00 ± 0.00 | 2.00 ± 0.00 |

| Metformin 45 mg/kg | 1.00 ± 0.00 | 2.00 ± 0.00 | 2.00 ± 0.00 |

| Normal control | 1.00 ± 0.00 | 2.00 ± 0.00 | 2.00 ± 0.00 |

Abbreviation: SD, standard deviation.

a Data were obtained from 3 slides.

b Cell distribution score of immunoreactive cells, 0: No immunoreactive cells; 1: < 10% immunoreactive cells; 2: 10 - 50% immunoreactive cells; 3: 51 - 80% immunoreactive cells; 4: > 80% immunoreactive cells.

c Staining intensity score, 0: No staining; 1: Weak (pale) staining intensity; 2: Moderate (bright) staining intensity; 3: Strong (dark) staining intensity.

d Immunoreactive score (IRS) = cell distribution score × staining intensity score, 0: No protein expression; 1 - 3: Low protein expression; 4 - 8: Moderate protein expression; 9 - 12: High protein expression.

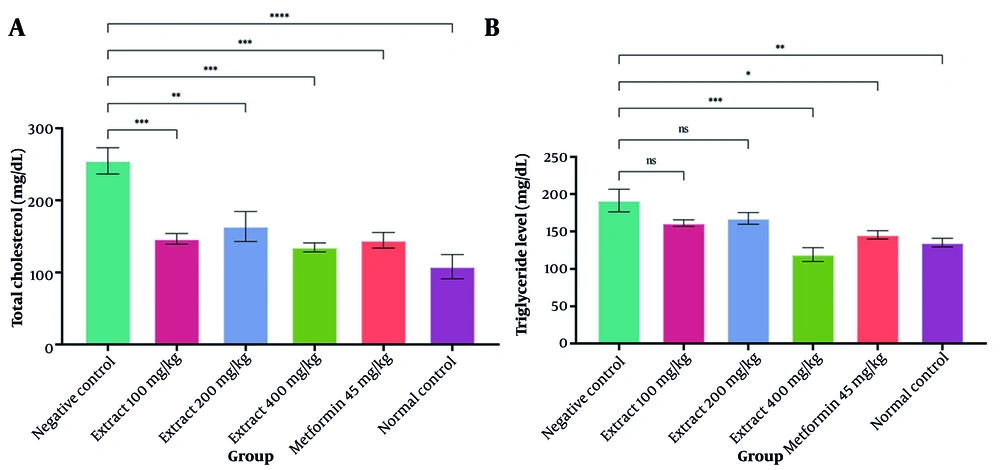

4.6. Lipid Profile

As illustrated in Figure 6, both the extract and metformin significantly lowered total cholesterol levels relative to the negative control group (P < 0.05). Administration of various extract doses did not significantly differ between the dose groups (P > 0.05). The total cholesterol levels in the extract groups at 100, 200, and 400 mg/kg doses were the same as those in the positive control group (P > 0.05). Administration of 400 mg/kg resulted in a significant reduction in triglyceride levels when compared with the untreated diabetic group (P < 0.05). In addition, increasing the extract dose significantly reduced triglyceride levels.

5. Discussion

A type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) model was induced using a high-fat and high-fructose diet, which promotes obesity, elevates circulating free fatty acids, glycerol, and leptin, and reduces adiponectin, collectively impairing insulin signalling (17). To further induce partial β-cell dysfunction without destruction, a single low dose of streptozotocin (25 mg/kg) was administered (17). This combined protocol is widely recognised as a reliable and reproducible approach for developing T2DM, as it mimics both insulin resistance and β-cell impairment. The treated animals subsequently exhibited persistent hyperglycemia, confirming successful model establishment.

Administration of S. bracteosa leaf extract for four weeks significantly reduced blood glucose and HbA1c levels. LC–MS analysis identified multiple secondary metabolites with antidiabetic potential. Rutin improves insulin sensitivity by inhibiting insulin receptor substrate-1 (IRS-1) phosphorylation and reducing suppressor of cytokine signalling 3 (SOCS3) activity. Furthermore, p-coumaric acid, apigenin, rutin, prunin, and oleanolic acid activate the phosphoinositide 3-kinase/protein kinase B (PI3K/Akt) pathway and enhance GLUT4 expression (18-22). Ursolic acid also ameliorates insulin resistance by activating Akt-GLUT4 signaling and exerting anti-inflammatory effects (23). Collectively, these compounds may act synergistically to improve insulin sensitivity and increase cellular glucose uptake. This is supported by immunohistochemical findings showing increased GLUT4 expression in the gastrocnemius muscle of extract-treated groups, confirming that enhanced insulin signalling contributes to the glucose-lowering effects.

The dose-response relationship in blood glucose reduction observed in weeks 3 and 4 indicated that further dose escalation no longer enhanced the therapeutic effect. This phenomenon may occur for several reasons. In pharmacodynamics, the ceiling effect (Emax) refers to the maximal response a drug can elicit. Once this plateau is reached, additional dose increases will not confer further benefit but may instead elevate the risk of adverse effects. This principle underlies the dosing limitations commonly observed with many antidiabetic agents (24).

Rutin, oleanolic acid, juglalin, and ursolic acid have been reported to enhance endogenous antioxidant defenses, including superoxide dismutase (SOD), catalase (CAT), and glutathione peroxidase (GPx), thereby reducing oxidative stress and suppressing inflammatory responses through inhibition of the NF-κB signalling pathway and downregulation of proinflammatory cytokines such as TNF-α and IL-1β (23, 25, 26). These protective effects are essential in preventing streptozotocin-induced pancreatic β-cell apoptosis. In addition, flavonoids have been shown to activate pancreatic and duodenal homeobox 1 (PDX-1), a key regulator of β-cell function and proliferation (27). Therefore, the secondary metabolites present in this extract may contribute not only to β-cell protection but also to β-cell regeneration. These findings are consistent with the present study, which demonstrated reduced β-cell injury and evidence of improved β-cell restoration following extract administration.

With respect to lipid regulation, flavonoids such as quercetin have been investigated as potential inhibitors of 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl-CoA reductase (HMG-CoA reductase) (28). Additionally, quercetin promotes cholesterol-to-bile acid conversion and cholesterol efflux. Meanwhile, triterpenoids such as ursolic acid have been identified to primarily target hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl coenzyme A synthase 1 (HMGCS1), a key upstream enzyme of HMG-CoA reductase in lipid metabolism (29). By acting on sequential steps of the mevalonate pathway, these compounds may exert synergistic effects in suppressing cholesterol biosynthesis. Additionally, quercetin is linked to the Akt signalling pathway. It regulates the expression of sterol regulatory element-binding proteins (SREBPs), which in turn control the expression of HMG-CoA reductase and the LDL receptor, both of which are crucial for maintaining cholesterol homeostasis (30). On the other hand, quercetin ameliorates hypertriglyceridemia by suppressing lipogenic proteins acetyl-CoA carboxylase (ACC), fatty acid synthase (FASN), and sterol regulatory element-binding protein-1c (SREBP-1c) while upregulating β-oxidation proteins such as peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor alpha (PPARα) and carnitine palmitoyltransferase 1a (CPT1A), thereby enhancing fatty acid catabolism and reducing triglyceride accumulation (31).

According to available evidence, fewer chemical constituents from S. bracteosa extract are known to reduce triglyceride levels compared to total cholesterol, suggesting that triglyceride modulation may only become significant at higher concentrations of the extract.

This study has several important limitations. LC-HRMS profiling was performed qualitatively, leaving the exact concentrations of the identified metabolites undetermined. Although immunohistochemistry demonstrated increased GLUT4 expression, it did not confirm membrane translocation, which would require more specific methods such as membrane fractionation or confocal imaging. The lack of variability in GLUT4 scores in the immunohistochemistry analysis stems from consistently strong staining across samples, which may partly result from the small number of animals and thus diminishes the ability to detect subtle biological differences. The small sample size (n = 4) may also have limited the statistical power to detect dose-dependent differences between treatment groups. However, the sample size was determined using the Federer formula and aligned with ethical considerations for animal use, and the observed outcomes consistently support the antidiabetic potential of the extract. Additionally, the absence of toxicity testing prevents firm conclusions about the extract’s safety profile. Therefore, future studies should include larger animal groups to improve statistical robustness, incorporate quantitative phytochemical analysis and molecular pathway validation (e.g., Western blot), and prioritize comprehensive toxicity evaluation as a critical prerequisite before the extract can be considered for therapeutic development.

5.1. Conclusion

S. bracteosa leaf extract demonstrated antidiabetic effects by reducing blood glucose and HbA1c levels, enhancing GLUT4 expression, preserving islet morphology, and improving lipid profiles (total cholesterol and triglycerides). LC-HR MS analysis identified 22 organic compounds that are likely responsible for these effects. Collectively, these findings highlight the potential of S. bracteosa as a plant-based therapeutic candidate for managing type 2 diabetes and its associated metabolic complications.