1. Background

The central nervous system (CNS) exhibits considerable susceptibility to oxidative stress (OS) attributable to factors such as elevated energy requirements, mitochondrial function, and the prevalence of polyunsaturated fatty acids (1). The modulation of inflammation and OS represents a prominent focus of contemporary research aimed at the formulation of novel therapeutic interventions for multiple sclerosis (MS) (2). The OS is implicated as a critical factor in the pathogenesis and progression of MS. Numerous investigations have revealed heightened levels of OS biomarkers in the serum and cerebrospinal fluid of individuals diagnosed with MS in comparison to healthy control subjects (3, 4). The OS instigates demyelination and neurodegeneration within the MS-affected brain through the oxidation of proteins, lipids, and DNA, in addition to precipitating mitochondrial damage (1). Active lesions associated with MS exhibit significant alterations in mitochondrial protein composition, deletions of DNA within neurons, and elevated concentrations of oxidized DNA in oligodendrocytes (5). The magnitude of oxidative damage is directly proportional to the degree of inflammation observed in MS lesions. Pentraxin-3 (PTX3) facilitates the phagocytic elimination of pathogens and apoptotic cells while concurrently fulfilling various immunoregulatory functions in the context of tissue injury. This protein is upregulated in microglia and macrophages in response to endogenous agonists such as heat shock protein B5, which accumulates within glial cells during the course of MS (6, 7). The findings from the search results suggest that PTX3 is integral to the pathogenesis and advancement of MS. Plasma concentrations of PTX3 exhibit a significant elevation in MS patients during periods of disease relapse when compared to healthy individuals (8). Furthermore, PTX3 levels are markedly elevated in the cerebrospinal fluid of patients exhibiting aggressive forms of MS and are also prominently expressed in microglia within preactive MS lesions (6), as well as in microglia/macrophages involved in myelin phagocytosis in actively demyelinating lesions (9). In MS, the immune system attacks and damages the myelin sheath that insulates nerve fibers in the CNS, leading to impaired nerve signal transmission and neurodegeneration. Neurofilament 200 (NF200; neurofilament heavy chain) is a protein that is often used as a marker for axonal MS (10). Studies have shown that NF200 levels are altered in MS. A decrease in NF200 signal density has been observed, indicating axonal damage (11, 12). The reduction in NF200 reflects the loss of axons and neurons that occurs in MS as a result of chronic inflammatory demyelination (10). Measuring NF200 can provide insights into the extent of axonal damage and neurodegeneration in MS patients. For a long time, non-pharmacological treatment methods have been used to control or treat MS. Meanwhile, physical activity and natural supplements are among the most popular non-invasive methods (13). Studies have found that coenzyme Q10 (CoQ10) supplementation can reduce peripheral OS and inflammation in MS patients treated with interferon beta-1a (14). Additionally, the impact of aquatic aerobic exercise on cortisol concentrations and transforming growth factor beta (TGF-β) has been investigated in MS patients, with positive results (15). Furthermore, CoQ10 supplementation combined with aquatic exercise (EX) training has been shown to improve OS, muscular strength, and myelin regeneration in human and animal models of MS (16). A study combining 8 weeks of CoQ10 supplementation and combined exercise training (with an aerobic dominant component) demonstrated improvements in motor function, fitness, and quality of life in healthy subjects (17) and also in MS patients (18). The researchers observed reductions in OS markers and increases in the expression of the neuroprotective protein NF200 in the animal model (19). Another study showed that CoQ10 supplementation, along with other nutrients, can have beneficial effects on exercise performance, muscle function, and inflammatory markers in healthy adults and athletes (18). The combined supplementation approach appears more promising than a single CoQ10 intervention, especially in populations with compromised nutrient reserves or metabolic conditions (19).

2. Objectives

The presents study aimed to investigate the effect of CoQ10 supplementation and EX on OS indices such as total antioxidant capacity (TAC), catalase (CAT), peroxidase (POX), and glutathione reductase (GR), as well as PTX3, Forkhead Box P3 (FOXP3), and NF200 protein expression. Additionally, the study examined the impact on glial cells, including oligodendrocytes and microglia, in a cuprizone (CPZ)-induced experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis (EAE) model.

3. Methods

3.1. Animals and Hippocampus Tissue Preparation

This study obtained approval from the Research Ethics Committee at Shahid Chamran University, Ahvaz, Iran (IR.SCU.REC.1402.042), adhering to the NIH Guidelines for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals (NIH publication, 1996). A total of 49 male Wistar rats, aged 12 weeks and weighing 250 ± 50 g, were randomly allocated into seven groups (n = 7): Healthy control group, healthy+EX group, healthy+COQ10 group, MS group, MS+EX group, MS+COQ10 group, MS+EX+COQ10 group. Initially, 12 rats were designated to each group, but due to significant mortality, only 49 rats survived and were subsequently divided. The animals were induced with MS using CPZ over a period of 6 weeks. Following this, interventions lasting 6 weeks, including aerobic training and CoQ10 supplementation, were implemented. The animals were housed in groups of seven in transparent polycarbonate cages. Four rats were maintained per cage within an animal laboratory, which was kept under a 12-hour light and 12-hour dark cycle, at a temperature of 25°C, with unrestricted access to food and water. The rats were allowed to acclimatize to their new environment for seven days. Subsequently, 48 hours after the final training session, the rats were anesthetized and euthanized using deep ketamine/xylazine (90/10 mg/kg), and the hippocampal tissue was extracted. After washing and weighing, the tissue samples were frozen at -70°C, and the research variables were subsequently measured. The following materials were utilized: Animal-specific pool, centrifuge, blotting device, scale, ELISA reader spectrophotometer, rotarod, insulin syringe, and saline solution.

3.2. Multiple Sclerosis Induction

To induce the MS model, animals were given a diet that included 0.2% (w/w) CPZ (bis-cyclohexanone oxaldihydrazone, Sigma-Aldrich). The CPZ was mixed into a standard ground rodent chow. Before the administration of CPZ, all rats participating in the study were acclimatized to powdered normal chow for one week. The CPZ diet was then maintained for six weeks until complete demyelination was observed (20).

3.3. Coenzyme Q10 Supplementation

The CoQ10 powder was sourced from Sigma Chemical Company, USA. The CoQ10 was administered daily at a dosage of 150 mg/kg/day, mixed in chow during the six weeks of training (21).

3.4. Training Protocol

The aquatic training program was conducted in the rodent pool. In the swimming exercise group, the animals swam for 30 minutes once a day, five days a week for six weeks. To help the animals adapt to the swimming training, the duration of the training was gradually increased from 10 minutes on the first day to 30 minutes by the sixth week (22).

3.5. Immunofluorescence Staining and Morphometric Analysis of Isolated Hippocampus

For the histopathological evaluation of the hippocampus, the brain was carefully extracted from the skull. The brains were then dissected and prepared for histological examination as described below. Using a light microscope with a magnification of 40x, parameters such as cytoplasmic staining and pancellular necrosis were assessed across five fields of each slide, which included five sections from the CA1 region of the hippocampus that were isolated and stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E). The physical dissector technique was utilized for the quantitative analysis of neurons. We counted the number of neurons within a 10,000 µm2 counting frame and subsequently calculated the mean neuron scores (NA) in the subdivisions of the hippocampus using the following formula: NA = ∑Q/∑P × AH (23).

3.6. Evaluation of Oxidative Stress Index in Hippocampal Tissue Using the Ferric Reducing Ability of Plasma Biochemical Assay

To evaluate the levels of CAT, TAC, and GR, standard kits were employed following the manufacturer’s instructions (RANDOX RANSOD, United Kingdom). Tissue samples were lysed in RIPA buffer with a homogenizer, followed by centrifugation at 10,000 rpm for 10 minutes. The supernatant was collected for the assessment of the parameters under study. The protein concentration in the tissue lysate was determined using the Bradford method. For the determination of Oxidative Stress Index (OSI), two parameters were assessed: Total oxidative status (TOS) and total antioxidant status (TAS). The OSI value was calculated by dividing TOS by TAS. The TAS measurement was conducted using the Erel method. In this assay, the colored compound 2,2'-azinobis-3-ethylbenzothiazoline-6-sulfonic acid (ABTS) is reduced in the presence of antioxidant compounds, resulting in a colorless solution. The change in absorbance at a wavelength of 660 nm corresponds to the antioxidant capacity. Trolox reagent served as a calibrator, and results were expressed as mmol Trolox equivalent/L. The TOS measurement was performed using the method outlined by Erel. This method is based on the oxidation of ferrous iron to ferric iron and the formation of a colored complex with xylenol orange, measurable at a wavelength of 560 nm. H2O2 was utilized as a calibrator, and results were reported as µmol H2O2 equivalent/L.

3.7. Glial Cell Assay

In the hippocampal histometry study, the number of oligodendrocytes was counted at 1000x magnification (for each slide in 10 microscopic fields) in sections of the dentate gyrus and subsequently compared (24).

3.8. Evaluation of Protein Expression Using Western Blot Method (Pentraxin-3 Assay)

Western blot analysis was conducted to assess protein expression levels of PTX3 using Ptx3 (C-10): SC-373951, SANTA CRUZ BIOTECHNOLOGY, INC. For the Western blot procedures, samples were initially homogenized using RIPA lysis buffer with a tissue homogenizer. Subsequently, samples were subjected to centrifugation at 12,000 rpm for a duration of 10 minutes at a temperature of 4°C, after which the supernatant was collected for further analyses. Protein concentrations were assessed utilizing the Bradford assay method. SDS-PAGE was conducted employing conventional techniques with 10% polyacrylamide gels and a continuous buffer system. Following the SDS-PAGE process, proteins were transferred to nitrocellulose membranes through standard blotting procedures using a transfer apparatus. The preparation of membranes was carried out in transfer buffer two hours prior to the assay. After the transfer of proteins to the nitrocellulose membranes, washing steps were executed, and blocking was performed using 5% skimmed milk. For the detection of target proteins, polyclonal primary antibodies specific to the proteins of interest were applied at a dilution of 1:200, followed by the use of HRP-conjugated polyclonal anti-rabbit IgG secondary antibodies. Visualization of the proteins was accomplished using DAB chromogen substrate. GAPDH or β-actin were utilized as loading controls. Densitometric analysis of the target protein bands in relation to GAPDH was conducted using MEGA5 software, with results expressed as arbitrary units in comparison to the calibrator protein expression (25).

3.9. Measurement of the Levels of Tissue Proteins by ELISA (Neurofilament 200, Forkhead Box P3 Assay)

The expression levels of NF200 and FOXP3 proteins were quantified using a species-specific ELISA kit. To prepare 20 mL of lysing buffer, the following components were combined: Fifty mM Tris base (0.3 g), 150 mM sodium chloride (0.43 g), 0.1% Triton X-100 (0.02 mL), 0.25% sodium deoxycholate (0.05 g), 0.1% SDS (0.02 g), and EDTA (5.84 g), along with 1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride (0.009 g) in 20 mL of distilled water. The mixture’s pH was adjusted to 7.4. After incorporating the specified ingredients, the final volume was adjusted to 50 mL with distilled water. For every 10 mL of the solution, 100 μL of a protease inhibitor mixture (Sigma, America) was added. Subsequently, 0, 2, 4, 6, 10, 15, and 20 microliters of BSA standard, along with 20 microliters of the tissue homogeneous sample, were dispensed into the wells of a 96-well plate. Each well received 40 microliters of Bradford’s reagent, followed by pipetting. Then, 200 microliters of distilled water were added to each well and the plate was allowed to sit at room temperature for 5 minutes. The absorbance of the samples was measured at a wavelength of 595 nm using a BioTek ELX800 (USA) microplate reader. The concentration of the samples was determined by plotting the standard curve of absorbance changes against the concentration of standard samples. The protein amount in the tissue homogeneous samples was calculated in terms of µg/mL by multiplying the value obtained from the standard curve by 50 (23, 26).

3.10. Statistical Analyses

The data were expressed as mean ± standard deviation (SD). The Shapiro-Wilk normality test was performed to confirm the normal distribution of the data. Levene’s test was utilized to evaluate the homogeneity of variances. A one-way ANOVA, followed by Tukey’s post hoc test, was conducted to analyze the data. All statistical analyses were executed using SPSS software version 21 for Windows (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA), with a significance threshold set at P < 0.05.

4. Results

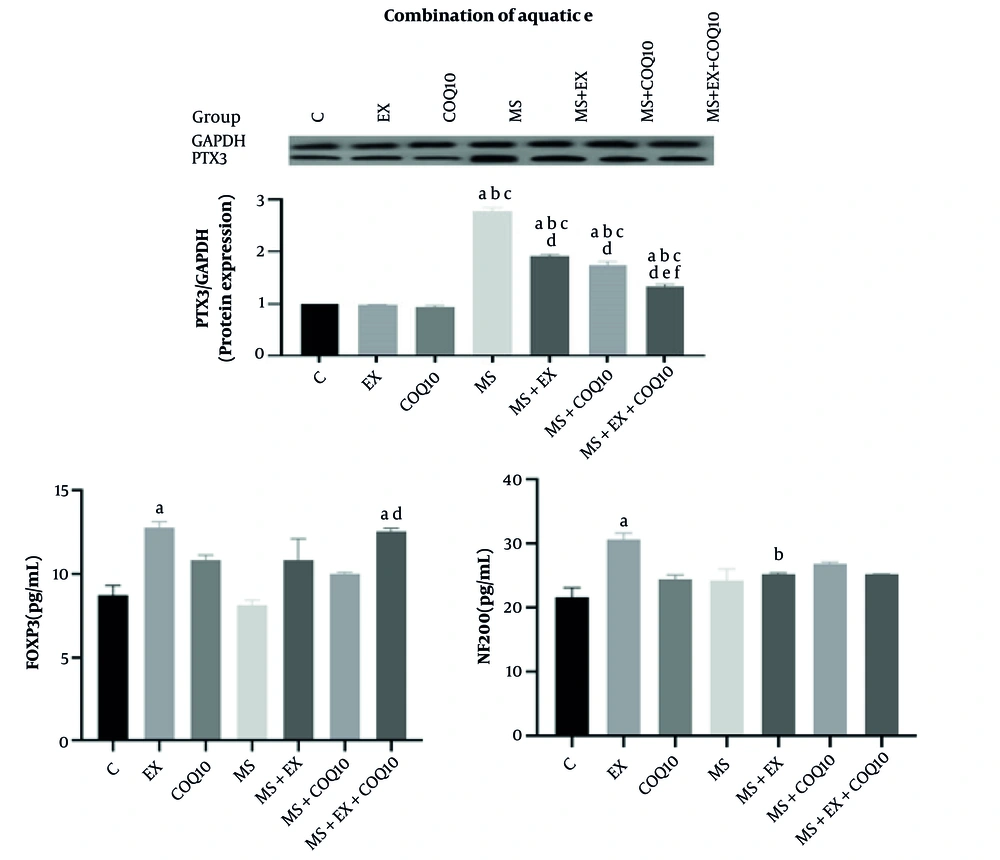

The results of the one-way ANOVA showed a significant difference between groups in NF200, PTX3, and FOXP3 protein expression (all, P ≤ 0.001) (Figure 1). Tukey post-hoc comparisons indicated that NF200 protein expression in the EX group significantly increased compared to the C group (P ≤ 0.017). Additionally, NF200 protein expression in the MS+EX group significantly decreased compared to the EX group (P ≤ 0.001). Tukey post-hoc comparisons showed that PTX3 protein expression in the MS, MS+EX, MS+CoQ10, and MS+EX+CoQ10 groups significantly increased compared to the control group (all, P ≤ 0.002), EX (all, P ≤ 0.001), and CoQ10 (all, P ≤ 0.001) groups. Furthermore, PTX3 protein expression in the MS+EX, MS+CoQ10, and MS+EX+CoQ10 groups significantly decreased compared to the MS group (all, P ≤ 0.001). The PTX3 protein expression in the MS+EX+CoQ10 group significantly decreased compared to the MS+EX and MS+CoQ10 groups (both, P ≤ 0.001) (Figure 1). Tukey post-hoc comparisons showed that NF200 protein expression in the MS group significantly increased compared to the control and EX groups (both, P ≤ 0.017). Additionally, NF200 protein expression in the MS+EX and MS+EX+CoQ10 groups significantly decreased compared to the MS group (both, P ≤ 0.001). The NF200 protein expression in the MS+EX+CoQ10 group significantly decreased compared to the MS+CoQ10 group (P = 0.031) (Figure 1). Tukey post-hoc comparisons showed that FOXP3 protein expression in the EX group significantly increased compared to the control group (P ≤ 0.020). The FOXP3 protein expression in the MS+EX+CoQ10 group significantly increased compared to the control and MS groups (both, P = 0.001) (Figure 1).

Neural proteins in study groups (Abbreviations: C, healthy control group; EX, healthy exercise group; COQ10, healthy coenzyme Q10 supplement group; MS, multiple sclerosis group; MS+EX, multiple sclerosis plus exercise group; MS+COQ10, multiple sclerosis plus coenzyme Q10 supplement group; MS+EX+COQ10, multiple sclerosis plus exercise plus coenzyme Q10 supplement group). a indicates significant difference compared to C; b indicates significant difference compared to EX; c indicates significant difference compared to COQ10; d indicates significant difference compared to MS; e indicates significant difference compared to MS+EX; f, significant difference compared to MS+COQ10.

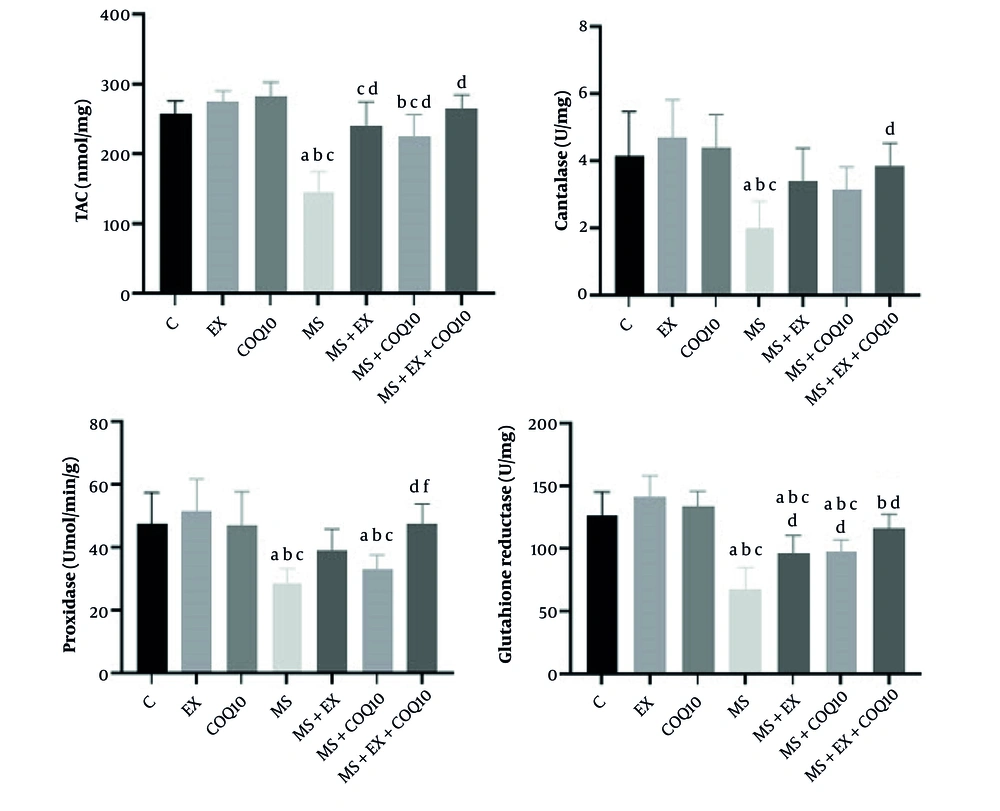

The results of the one-way ANOVA showed significant differences between groups in TAC, CAT, POX, and GR (all, P ≤ 0.001) (Figure 2). Tukey post-hoc comparisons indicated that TAC in the MS group significantly decreased compared to the C group (P ≤ 0.001). Additionally, TAC in the MS and MS+CoQ10 groups significantly decreased compared to the EX group (both, P ≤ 0.009). Furthermore, TAC in the MS, MS+EX, and MS+CoQ10 groups significantly decreased compared to the CoQ10 group (all, P ≤ 0.043). The TAC in the MS+EX, MS+CoQ10, and MS+EX+CoQ10 groups significantly increased compared to the MS group (both, P ≤ 0.001). Tukey post-hoc comparisons showed that CAT in the MS group significantly decreased compared to the C, EX, and CoQ10 groups (P ≤ 0.003). Additionally, CAT in the MS+EX+CoQ10 group significantly increased compared to the MS group (P = 0.014) (Figure 2). Tukey post-hoc comparisons showed that POX in the MS and MS+CoQ10 groups significantly decreased compared to the C, EX, and CoQ10 groups (all, P ≤ 0.024). The POX in the MS+EX+CoQ10 group significantly increased compared to the MS (P ≤ 0.001) and MS+CoQ10 groups (P = 0.022). Tukey post-hoc comparisons showed that GR in the MS, MS+EX, and MS+CoQ10 groups significantly decreased compared to the control, EX, and CoQ10 groups (all, P ≤ 0.010). The GR in the MS+EX, MS+CoQ10, and MS+EX+CoQ10 groups significantly increased compared to the MS group (P ≤ 0.013) (Figure 2).

Oxidant/anti-oxidant factors in study groups. (Abbreviations: C, healthy control group; EX, healthy exercise group; COQ10, healthy Coenzyme Q10 supplement group; MS, multiple sclerosis group; MS+EX, multiple sclerosis plus exercise group; MS+COQ10, multiple sclerosis plus Coenzyme Q10 supplement group; MS+EX+COQ10, multiple sclerosis plus exercise plus Coenzyme Q10 supplement group). a indicates significant difference compared to C; b indicates significant difference compared to EX; c indicates significant difference compared to COQ10; d indicates significant difference compared to MS; and f indicates significant difference compared to MS+COQ10.

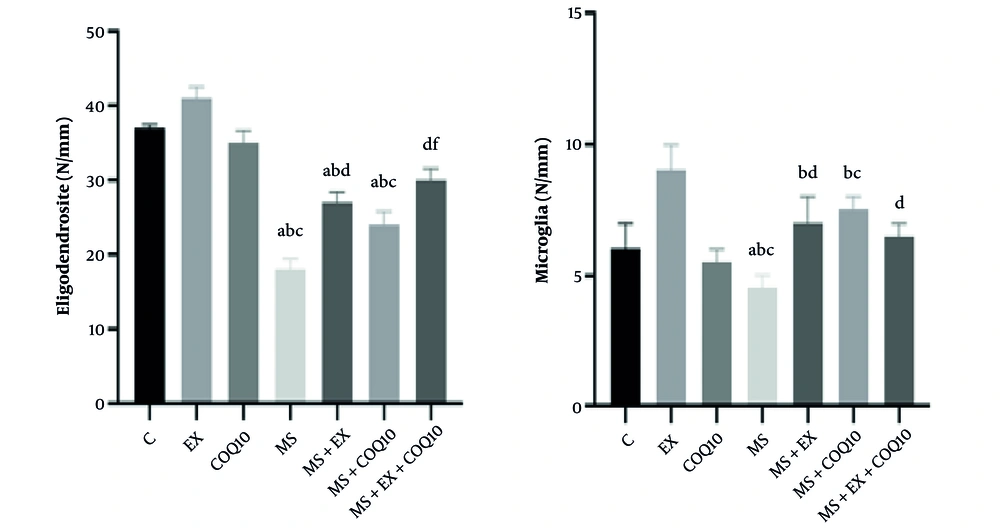

The results of the one-way ANOVA showed significant differences between groups in oligodendrocyte number and microglia number (all, P ≤ 0.001) (Figure 3). Tukey post-hoc comparisons indicated that the oligodendrocyte number in the MS, MS+EX, and MS+CoQ10 groups significantly decreased compared to the control group (all, P ≤ 0.030), EX (all, P ≤ 0.002), and CoQ10 (all, P ≤ 0.046) groups. Additionally, the oligodendrocyte number in the MS+EX and MS+EX+CoQ10 groups significantly increased compared to the MS group (both, P ≤ 0.001). The oligodendrocyte number in the MS+CoQ10 group significantly decreased compared to the MS+EX group (P = 0.039), and in the MS+EX+CoQ10 group, it significantly increased compared to the MS+CoQ10 group (P ≤ 0.001) (Figure 3). Tukey post-hoc comparisons showed that the microglia number in the MS group significantly increased compared to the control group (P ≤ 0.001). Additionally, the microglia number in the MS, MS+EX, and MS+CoQ10 groups significantly increased compared to the EX group (all, P ≤ 0.048). Furthermore, the microglia number in the MS and MS+CoQ10 groups significantly increased compared to the CoQ10 group (both, P ≤ 0.002). The microglia number in the MS+EX and MS+EX+CoQ10 groups significantly decreased compared to the MS group (both, P ≤ 0.008) (Figure 3).

Glial cells in study groups. (Abbreviations: C, healthy control group; EX, healthy exercise group; COQ10, healthy Coenzyme Q10 supplement group; MS, multiple sclerosis group; MS+EX, multiple sclerosis plus exercise group; MS+COQ10, multiple sclerosis plus Coenzyme Q10 supplement group; MS+EX+COQ10, multiple sclerosis plus exercise plus Coenzyme Q10 supplement group). a indicates significant difference compared to C; b indicates significant difference compared to EX; c indicates significant difference compared to COQ10; d indicates significant difference compared to MS; and f indicates significant difference compared to MS+COQ10.

5. Discussion

The findings of the present study demonstrated that the combination of EX and CoQ10 supplementation significantly reduces OS, PTX3 protein expression, and microglial count in the CPZ-induced demyelination animal model, while simultaneously increasing FOXP3 protein expression and oligodendrocyte count. No statistical changes were found in the protein expression of NF200 after interventions. These results indicate the beneficial combinatorial effects of these interventions on inflammation reduction, antioxidant status improvement, and neuroprotection in the hippocampal tissue of rats with MS. The significance of these findings in the context of MS lies in the recognition that OS and inflammation are key factors in the pathogenesis and progression of this disease, and non-pharmacological interventions such as EX and natural supplements like CoQ10 may be considered as complementary approaches in MS management. This study specifically demonstrated that the combined intervention (EX+CoQ10) had stronger effects on inflammatory and neurological markers compared to each intervention alone, which could contribute to the development of novel therapeutic strategies for MS.

The study results showed that TAC, CAT, POX, and GR were significantly decreased in the MS group, which is consistent with previous findings regarding the role of OS in MS pathogenesis (1). Aquatic exercise and CoQ10 supplementation, both individually and in combination, improved these indices, particularly in the MS+EX+CoQ10 group, which showed significant increases in TAC, CAT, POX, and GR compared to the MS group. The CoQ10 is recognized as a potent antioxidant that reduces OS by neutralizing reactive oxygen species (ROS) and strengthening the mitochondrial electron transport chain (14). Aquatic exercise also contributes to improved oxidative status by increasing the expression of antioxidant enzymes such as CAT and GR and reducing inflammation-induced ROS production (16). The combination of these two interventions likely produced stronger effects through the synergy of antioxidant and anti-inflammatory mechanisms.

The PTX3 protein expression, as an inflammatory marker, was significantly increased in the MS group, which is consistent with previous studies showing elevated PTX3 in cerebrospinal fluid and plasma of MS patients during disease relapse phases (7, 8). The PTX3 is prominently expressed in microglia and macrophages in active MS lesions and plays an important role in myelin phagocytosis and inflammation regulation (6). In the present study, EX and CoQ10 individually reduced PTX3 expression, but the MS+EX+CoQ10 group showed a more significant reduction compared to the MS+EX and MS+CoQ10 groups. This reduction may be attributed to the anti-inflammatory effects of EX through decreased pro-inflammatory cytokines and CoQ10’s ability to inhibit inflammatory pathways such as NF-κB (14). The reduction in PTX3 may indicate decreased microglial activity and an improved anti-inflammatory environment in the CNS, which is crucial for reducing MS disease progression.

The NF200 protein expression, recognized as an indicator of axonal integrity and neuronal health, was increased in the MS group, possibly due to a compensatory response to axonal damage (10). However, in the MS and EX groups, NF200 expression was significantly increased, which may indicate an elevated need for a compensatory response due to neuroprotection resulting from the interventions. Aquatic exercise likely contributes to maintaining axonal integrity by improving cerebral blood flow and increasing the production of neurotrophic factors such as BDNF (22). On the other hand, CoQ10 protects neurons against degeneration by reducing OS and mitochondrial damage (27). The combination of these two interventions may have synergistic effects on preserving axonal structure and improving neurological function through strengthening neuroprotective pathways and reducing inflammation.

The results showed that the MS+EX+CoQ10 group demonstrated greater improvements in OS indices, PTX3, oligodendrocyte count, and microglial count compared to the MS+EX and MS+CoQ10 groups. These synergistic effects may be due to the combination of CoQ10’s antioxidant and anti-inflammatory mechanisms with the neuroprotective and anti-inflammatory effects of EX. Aquatic exercise may improve CoQ10 accessibility to CNS tissues by increasing metabolism and improving blood flow, while CoQ10 enhances the positive effects of exercise by reducing OS (19). This synergy demonstrates the potential of combinatorial approaches in managing neurodegenerative diseases such as MS.

The findings of this study are consistent with previous research examining the positive effects of exercise and CoQ10 in MS. For example, Moccia et al. (14) showed that CoQ10 supplementation in MS patients undergoing interferon-beta1a treatment reduces OS and peripheral inflammation. Similarly, Bansi et al. (22) reported that EX reduces pro-inflammatory cytokine concentrations and increases neurotrophic factors in MS patients. However, the present study demonstrated that this combination has stronger effects than each intervention alone. This finding is consistent with the study by Ahmadi et al. (19), which showed that the combination of combined exercise and CoQ10 improves motor function and reduces inflammatory markers in MS patients. However, unlike some studies that focused on clinical symptom improvement, the present study focused on molecular and tissue markers and provides new information about underlying mechanisms.

In comparison with other neurodegenerative diseases, such as Parkinson’s disease, Shults et al. (27) showed that CoQ10 can slow functional decline in the early stages of the disease, which is consistent with our findings regarding the neuroprotective effects of CoQ10. However, there are differences in the severity of observed effects, which may be related to pathophysiological differences between MS and other neurodegenerative diseases. The CoQ10, a potent antioxidant, plays a pivotal role in mitigating OS. This compound safeguards neuronal cells against oxidative harm by neutralizing ROS and improving the efficiency of the mitochondrial electron transport chain (28, 29). Similarly, EX bolsters antioxidant status by upregulating the expression of antioxidant enzymes, such as CAT and GR, while reducing inflammation-induced ROS production (16). In the present study, the combined intervention of CoQ10 and EX significantly elevated TAC, as well as levels of CAT, POX, and GR in the EX+CoQ10 group. These results suggest a reinforced antioxidant defense system against OS, likely attributable to the synergistic effects of CoQ10 in amplifying endogenous antioxidant mechanisms and EX in diminishing ROS levels (19).

Furthermore, EX and CoQ10 modulate the expression of inflammatory proteins, such as PTX3, through anti-inflammatory and neuroprotective pathways. The PTX3, an inflammatory marker, is elevated in microglia and macrophages within MS lesions (6). Aquatic exercise fosters an anti-inflammatory milieu by decreasing pro-inflammatory cytokines and increasing anti-inflammatory factors (22, 30). Concurrently, CoQ10 attenuates inflammation by inhibiting pathways such as NF-κB (14). In this study, reduced PTX3 expression in the intervention groups, particularly MS+EX+CoQ10, reflects diminished inflammatory activity. Conversely, it may indicate a decreased requirement for compensatory responses to axonal injury, correlating with the neuroprotective effects of these interventions (10). Additionally, EX enhances cerebral blood flow and increases brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) levels, while CoQ10 mitigates mitochondrial damage, collectively contributing to the preservation of axonal integrity and neuronal health (31).

The findings of this study have potential implications for MS treatment in humans. Aquatic exercise, due to its low-impact nature and suitability for patients with mobility limitations, is an attractive non-pharmacological intervention (32). The CoQ10, due to its high safety profile and availability as a dietary supplement, is also a suitable option for use alongside standard MS treatments (14). The combination of these two interventions could be used as part of a comprehensive approach to reduce inflammation, improve antioxidant status, and protect neurons in MS patients (19). Future research could focus on examining the long-term effects of the combination of EX and CoQ10 in animal and human models. Dose-response studies are needed to determine the optimal amount of CoQ10 and intensity/duration of EX. Furthermore, examination of additional biomarkers, such as neurotrophic factors (like BDNF) or anti-inflammatory cytokines (like IL-10), could provide a better understanding of therapeutic mechanisms. Conducting randomized clinical trials in MS patients to confirm the effects observed in this study is essential. Additionally, examining the effects of these interventions on other aspects of MS pathology, such as myelin regeneration or cognitive function, could clarify the therapeutic value of this approach.

The synergistic effects of CoQ10 and exercise in MS management are mediated through complementary molecular pathways that reduce OS and inflammation, key contributors to MS pathology. The CoQ10, a vital mitochondrial antioxidant, activates the NRF2 pathway, a master regulator of antioxidant defenses, increasing the expression of enzymes like superoxide dismutase (SOD), which mitigates oxidative damage (14). Exercise, particularly combined aerobic and resistance training, enhances neuroprotection and remyelination by upregulating BDNF while suppressing the pro-inflammatory NF-κB pathway, reducing inflammatory markers such as tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) and interleukin-6 (IL-6) (33). Clinical studies demonstrate that CoQ10 supplementation (200 - 500 mg daily) combined with exercise improves motor function and reduces fatigue in MS patients (34). However, some evidence suggests exercise alone may have a more pronounced effect on physical function, while CoQ10 primarily contributes to reducing inflammation and OS (35).

This study has several limitations. First, the use of the CPZ animal model may not fully reflect the pathophysiology of human MS, as this model focuses more on demyelination rather than autoimmune inflammation. Second, the small sample size (n = 7 per group) may have limited the statistical power of the study. Third, the intervention duration (6 weeks) may not be sufficient to assess long-term effects. Also, the lack of assessment of stress markers may have affected the results. Additionally, measurement techniques such as Western blot and immunofluorescence may be influenced by technical variables such as sample quality or method sensitivity. These limitations should be considered in interpreting results and designing future studies.

5.1. Conclusions

This study demonstrated that the combination of EX and CoQ10 supplementation can significantly reduce OS, inflammation, and neuronal damage in an animal model of MS and produce synergistic effects compared to individual interventions. These findings emphasize the potential of combined non-pharmacological and pharmacological approaches in MS management and pave the way for future research toward developing complementary treatments for this disease. Given the safety and accessibility of these interventions, they could be considered as part of a comprehensive strategy for improving the quality of life of MS patients. Given that MS is a chronic and progressive disease, these interventions could improve patients’ quality of life and slow disease progression. However, translating these findings to clinical practice requires carefully designed human studies.