1. Background

Manna is a sugary and adhesive secretion generated on certain plants due to the feeding activity of specific insects (1). Among the various types of manna that arise from the interactions between plants and insects, several significant types find application not only in the realm of medicine but also in the food and confectionery industries (2, 3). Oak manna, or Gazo in Kurdish, or Gaz-e-Alafi in Persian, is considered one of the main types of manna (4). Gazo refers to sweet, crystalline formations or droplets that naturally form on the leaves and young branches of the Fagaceae family. It is a highly concentrated nectar produced through the feeding activity of adult nymphs or insects belonging to the Thelaxes suberi and Tuberculatus annulatus species (1, 5, 6). These insects primarily feed on the leaves and young branches of three local oak species: "Barodar" (Quercusbrantii Lind), "Mazodar" (Q. infectoria Olive), and "Libani" (Q. libani Olive), all of which belong to the Fagaceae family (1, 2, 7). These oak trees are characterized by their impressive height, often reaching 15 - 20 meters, and possess thick deciduous leaves that are elongated or oval-shaped with serrated edges. They also feature robust trunks and are widely distributed in the forests of Kurdistan, particularly in the northern region of the Zagros Mountains (1, 8). The host plants, including Barodar, Mazodar, and Libani oaks, can be found in various habitats, ranging from lowlands and wetlands to dry and elevated hills. They bear male flowers in elongated clusters, while the female flowers are enclosed in full cups and give rise to single hairy fruits (2). It has been suggested that the optimal conditions for breeding aphids, the insects responsible for producing manna, are found in Kurdistan of Iran, Iraq, and Turkey (1, 9). A comprehensive examination of the cultivation history of the oak manna-producing tree reveals that the majority of these plants thrive in extensive regions within the western part of Iran, the eastern part of Turkey, and Iraqi Kurdistan (Kurdistan region) (1, 4).

The exploration of the biochemical characteristics of oak manna offers valuable insights into its potential therapeutic properties and biological activities. Through qualitative and quantitative analysis, we aim to identify the chemical constituents present in oak manna and gain a better understanding of the bioactive compounds responsible for its medicinal properties.

2. Objectives

This analysis focuses on the examination of sugars, amino acids, and proteins. A comprehensive analysis of the biochemical ingredients in oak manna contributes to our understanding of its origin and the ecological interactions between the host plants, insects, and the resulting nectar. The findings will not only expand our knowledge about this natural substance but also open doors for its utilization in various industries, including food, pharmaceuticals, and nutraceuticals.

3. Methods

3.1. Gazo Source, Chemicals, and Reagents

Leaves of Q. infectoria were collected in July 2023 from Bardarash-Sotue village, Baneh County, Kurdistan province, Iran (36°11'23.3"N 45°43'49.0"E; elevation 1620 m). Plant identification was confirmed by a taxonomist at the University of Kurdistan. To gather the bright brown powder of Gazo, the leaves are shaken after they have been dried in the open air. Then, the Gazo is collected into a clean container and transported to the Biochemistry lab for analysis of its biochemical components, which are stored at -20°C until further analysis. Chemicals included HPLC-grade acetonitrile (ACN) and formic acid (≥ 98%) from Sigma-Aldrich (USA), methanol (Merck, Germany), and ultrapure water (Milli-Q system, Millipore, USA). Analytical standards of glucose, fructose, sucrose, maltose, and raffinose were purchased from Merck (Germany). All solvents and reagents used were of LC-MS grade.

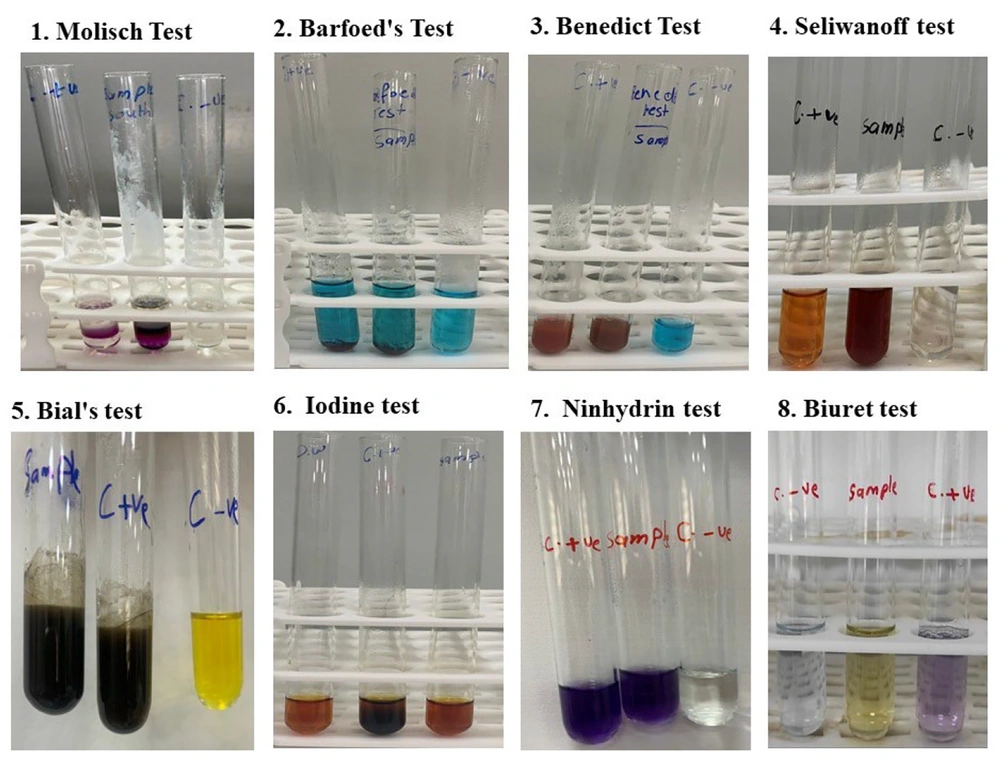

3.2. Qualitative Tests

To evaluate the presence of sugars, amino acids, and proteins, 5 grams of Gazo powder is dissolved in distilled water. Then, it was filtered using a paper filter and preserved in the refrigerator. Sugars, reducing sugars, keto sugars, starch, pentoses, amino acids, and total protein were assessed by Molisch test, Barfoed’s test, Benedict test, Seliwanoff test, Iodine test, Bial’s test, Ninhydrin test, and Biuret test, respectively. Biochemical assays were performed as follows.

3.2.1. Molisch’s Test

To 2 mL of sample solution, 2 drops of 5% α-naphthol in ethanol (Sigma-Aldrich) were added, followed by the careful addition of 1 mL concentrated H2SO4 (Merck) along the tube wall. The formation of a violet ring at the interface indicated carbohydrates.

3.2.2. Barfoed’s Test

1 mL of sample was mixed with 2 mL Barfoed’s reagent [0.33 M copper (II) acetate in 1% acetic acid, Merck] and heated in a boiling water bath for 2 minutes. A red precipitate of cuprous oxide confirmed monosaccharides.

3.2.3. Bial’s Test

To 2 mL of sample, 2 mL of Bial’s reagent [0.4% orcinol and 0.1% FeCl3 in concentrated hydrochloric acid (HCl), Sigma] was added and heated in a boiling water bath for 5 minutes. A green to blue-green color indicated pentoses.

3.2.4. Benedict’s Test

1 mL of sample was added to 2 mL Benedict’s reagent (alkaline copper citrate solution; Sigma) and boiled for 5 minutes. A red to orange precipitate indicated reducing sugars.

3.2.5. Seliwanoff’s Test

To 2 mL of the sample, 2 mL of freshly prepared Seliwanoff’s reagent (0.05 g resorcinol in 33 mL concentrated HCl, Merck) was added, and the mixture was heated in a boiling water bath for 2 minutes. A cherry-red color confirmed ketohexose (fructose).

3.2.6. Iodine Test

1 mL of the sample was mixed with 2 drops of iodine solution (0.01 M iodine in 0.02 M KI, Merck). A blue-black color indicated starch; the absence of color change confirmed the lack of polysaccharides.

3.2.7. Ninhydrin Test

1 mL of sample was mixed with 2 mL of 1% ninhydrin in ethanol (Sigma) and heated in a boiling water bath for 5 minutes. A purple color indicated free amino acids.

3.2.8. Biuret Test

To 2 mL of the sample, 2 mL of Biuret reagent [1% CuSO4 in 10% sodium hydroxide (NaOH), Merck] was added and mixed. The formation of a violet color indicated peptide bonds and proteins.

All tests were carried out in triplicate using analytical-grade reagents. Observations were compared with positive and negative controls (standard glucose, fructose, glycine, and bovine serum albumin).

3.3. Quantitative Tests

3.3.1. LC-MS/MS Analysis for Quantification of Carbohydrates

3.3.1.1. Sample Preparation

One gram of Gazo powder was weighed and extracted with 10 mL of 80% ethanol-water (v/v) in a centrifuge tube. The mixture was sonicated for 30 minutes at room temperature, followed by centrifugation at 10,000 rpm for 10 minutes. The supernatant was filtered through a 0.22 µm nylon filter, diluted as needed, and transferred to LC-MS vials.

3.3.1.2. Standard Solutions and Calibration

Stock solutions of carbohydrate standards (1 mg/mL) were prepared in water and serially diluted to obtain working standards ranging from 0.1 to 10 µg/mL. Calibration curves were generated using peak areas versus concentrations. Results were converted to % weight by calculating the carbohydrate content per gram of manna powder and expressing it as a percentage (% w/w).

3.3.1.3. LC-MS/MS Analysis

Chromatographic separation was performed on an Agilent 1290 Infinity UHPLC coupled to an Agilent 6460 Triple Quadrupole MS (Agilent Technologies, USA) using a Waters XBridge HILIC column (2.1 × 150 mm, 3.5 µm) at 35°C. The mobile phases were solvent A (ACN + 0.1% formic acid) and solvent B (water + 0.1% formic acid), with a gradient of 80 - 50% A over 20 minutes, and a flow rate of 0.3 mL/min. Data were processed using Mass Hunter or Analyst software. Quantification was based on external calibration curves. Sugar concentrations were calculated in mg/g dry weight and converted to % weight (% w/w) for each sample. Linearity (R2 > 0.99) and repeatability (RSD < 5%) were confirmed.

3.3.2. Determination of Protein Content by Kjeldahl Method

The crude protein content of the Gazo powder was determined using the Kjeldahl method, following standard procedures. Approximately 0.5 g of Gazo powder was digested with concentrated H2SO4 in the presence of a catalyst mixture of potassium sulfate and copper sulfate (10:1, w/w) at 410°C until a clear solution was obtained. The digested sample was then subjected to distillation after neutralization with 40% NaOH. The released ammonia was distilled into a receiving flask containing boric acid solution and then titrated with 0.1 N HCl. The nitrogen content was calculated and converted to protein by multiplying by a nitrogen-to-protein conversion factor of 6.25. The results were expressed as a percentage of protein content (% w/w) (10).

3.3.3. Amino Acid Analysis by HPLC

3.3.3.1. Sample Preparation and Hydrolysis

Approximately 1.0 g of Gazo powder was hydrolyzed with 10 mL of 6 N HCl in sealed glass ampoules under nitrogen and heated at 110°C for 24 hours. After cooling, the hydrolysate was filtered and evaporated to dryness under reduced pressure at 40°C. The residue was reconstituted in 1 mL of 0.1 M HCl, filtered through a 0.22 µm membrane, and subjected to derivatization.

Pre-column derivatization was performed with O-phthalaldehyde (OPA) for primary amino acids and 9-fluorenylmethyl chloroformate (FMOC) for secondary amino acids. For each sample, 10 µL of extract was mixed with 10 µL of derivatizing reagent and incubated briefly before injection. Separate conditions were used for primary and secondary amino acids.

HPLC amino acid analysis was performed on a Shimadzu LC-20AT system with a fluorescence detector, using an Agilent ZORBAX Eclipse Plus C18 column (4.6 × 250 mm, 5 µm) at 35°C. Solvents were phosphate buffer (10 mM, pH 7.2) and ACN:water:methanol (45:45:10, v/v/v) (11). Standard mixtures of amino acids (ranging from 1 to 100 mg/L) were used to construct calibration curves. Quantification was based on peak area using external standards. Concentrations were expressed as mg of amino acid per kg of Gazo powder (mg/kg dry weight). Data were processed using ChemStation software. Calibration curves showed excellent linearity (R2 > 0.995) for all analytes.

3.4. Statistical Analysis

All experiments were conducted in triplicate, and results were expressed as mean ± standard deviation (SD). All statistical analyses were conducted using IBM SPSS Statistics and Microsoft Excel.

4. Results

4.1. Qualitative Biochemical Analysis

The preliminary qualitative tests confirmed the presence of various classes of biomolecules in Gazo. Carbohydrates were detected through multiple assays, including Molisch’s test (general carbohydrate test), Barfoed’s test (monosaccharides), Bial’s test (pentoses), Benedict’s test (reducing sugars), and Seliwanoff’s test (ketoses), all of which yielded positive results. However, the iodine test for polysaccharides (starch) was negative, indicating an absence of complex carbohydrates in the sample. For amino acids, a positive reaction was observed with the Ninhydrin test, confirming their presence. In contrast, the Biuret test yielded a negative result, suggesting that intact or high-molecular-weight proteins were not detectable in the sample (Table 1 and Figure 1).

| Biochemical Molecules | Qualitative Test | Results |

|---|---|---|

| Carbohydrates | Molisch test | Positive |

| Monosaccharides | Barfoed’s test | Positive |

| Pentoses | Bails test | Positive |

| Reducing sugars | Benedict's test, Osazone test | Positive |

| Ketoses | Seliwanoff test | Positive |

| Polysaccharides (starch) | Iodine test | Negative |

| Amino acids | Ninhydrin tests | Positive |

| Proteins | Biuret test | Negative |

4.2. Quantitative Biochemical Composition

4.2.1. Carbohydrate Content

Quantitative analysis of Gazo revealed the presence of several simple and disaccharide sugars, reported as a percentage of dry weight. The predominant sugar was sucrose (11.79%), followed by maltose (5.98%) and glucose (2.95%). Fructose was not detected, and its concentration was not reported. Notably, no detectable levels of sugar alcohols such as sorbitol, mannitol, or xylitol were found (Table 2).

| Types of Biomolecules | Result |

|---|---|

| Carbohydrates (% wt.) | |

| Monosaccharide-glucose | 2.90 ± 0.45 |

| Monosaccharide- fructose | ND |

| Disaccharide-sucrose | 11.70 ± 0.84 |

| Disaccharide-maltose | 5.90 ± 0.65 |

| Alcoholic sugar- sorbitol | ND |

| Alcoholic sugar- mannitol | ND |

| Alcoholic sugar- xylitol | ND |

| Amino acids (mg/kg) | |

| Glycine | 10.90 ± 2.23 |

| Alanine | 76.20 ± 7.65 |

| Leucine | 5659.40 ± 73.54 |

| Isoleucine | 5550.10 ± 93.58 |

| Methionine | 49.50 ± 8.96 |

| Proline | 1523.70 ± 58.64 |

| Serine | 21.80 ± 4.61 |

| Threonine | 3722.20 ± 91.12 |

| Valine | 3809.30 ± 56.13 |

| Phenylalanine | 1358.50 ± 41.87 |

| Other amino acids | ND |

| Protein (%wt.) | 2.10 ± 0.32 |

Abbreviation: ND, not detected.

a Values are expressed as mean ± standard deviation (SD).

4.2.2. Amino Acid Profile

The amino acid composition of Gazo was quantified in milligrams per kilogram. Leucine (5,659 mg/kg), isoleucine (5,550 mg/kg), valine (3,809.30 mg/kg), and threonine (3,722.20 mg/kg) were the most abundant amino acids, highlighting a notable presence of branched-chain amino acids (BCAAs). Other amino acids, such as proline (1,523.7 mg/kg), phenylalanine (1,358.50 mg/kg), alanine (76.20 mg/kg), and methionine (49.50 mg/kg) were also detected in varying amounts. The presence of glycine and serine was minimal, with concentrations of 10.90 mg/kg and 21.80 mg/kg, respectively. Other amino acids were not detected.

4.2.3. Protein Content

Despite the presence of free amino acids, total protein content was relatively low, estimated at 2.18% of the dry weight.

5. Discussion

This study presents a detailed biochemical analysis of Gazo, a natural exudate derived from Quercus species. Our findings confirm the presence of abundant mono- and disaccharides, along with several essential and BCAAs, while revealing minimal levels of intact protein and no detectable starch or sugar alcohols. These attributes support the traditional use of Gazo as both a sweetening and medicinal agent, while also opening avenues for its nutritional and functional characterization.

The carbohydrate profile of Gazo was dominated by sucrose, maltose, and glucose, consistent with previous reports on plant-derived manna (1). Qualitative assays confirmed reducing sugars and monosaccharides, while the negative iodine test indicated the absence of starch — a feature uncommon among plant exudates, many of which contain polysaccharides that affect texture and viscosity (4). The absence of complex carbohydrates may enhance digestibility and contribute to the glycemic impact of Gazo, as its simple sugars are rapidly absorbed. Quantitative LC-MS/MS analysis further verified these results and confirmed the lack of mannitol, a sugar alcohol typically abundant in other manna such as those from Cotoneaster or Fraxinus species (12). This absence distinguishes Gazo from other regional mannans. For example, Fakhri et al. reported mannitol as the predominant sugar in Cotoneaster manna (12), whereas Łuczaj et al. showed that Gazo from Q. brantii acorns in Turkey contained only simple carbohydrates and lacked sugar alcohols (6). Furthermore, they reported that Gazo is traditionally produced through the collection and boiling of acorn exudates, leading to a high-viscosity product consumed for both dietary and medicinal purposes, particularly for bronchitis, diabetes, and as a nutritive agent (6). Such differences likely reflect taxonomic, ecological, and microbial factors influencing manna formation and highlight that not all mannans are functionally equivalent, underscoring the need for standardized biochemical profiling.

In addition to its carbohydrate composition, our results showed that Gazo is enriched in essential amino acids, particularly BCAAs such as leucine, isoleucine, and valine. Although the Biuret test was negative, indicating the absence of intact proteins, the Kjeldahl method revealed 2.18% protein content, attributable to free amino acids and small peptides that contribute nitrogen but do not form peptide bonds detectable by Biuret. Thus, Gazo contains nitrogen-rich components without intact protein structures, further supporting its role as an energy-dense and restorative substance.

Beyond its nutritional value, accumulating evidence suggests that Quercus-derived manna also possesses pharmacological potential. Al Safi et al. reported that Gaz alafi, another Q. brantii-derived manna, contains significant levels of phenolic compounds such as gallic acid and catechin, which exhibit antioxidant, antimicrobial, and anticancer activities (9). Similarly, Łuczaj et al. highlighted its traditional use in managing respiratory illnesses and fatigue (6). These findings provide a plausible mechanistic basis for the ethnobotanical uses of Gazo and align with its traditional application in managing fatigue, bronchitis, and gastrointestinal ailments. While our study did not directly assess phenolic content or bioactivity, the botanical origin and cultural usage patterns strongly suggest that Gazo may share these health-related properties.

Taken together, the biochemical profile of Gazo — characterized by rapidly digestible sugars, essential amino acids, and potential bioactive compounds — supports both its nutritional and medicinal relevance. The absence of starch and oligosaccharides may make it particularly suitable for individuals sensitive to complex carbohydrates. However, its health-related effects remain largely inferential at this stage. Future research should focus on exploring the phenolic composition, antioxidant capacity, antimicrobial potential, and clinical implications of Gazo, as well as its regional variability and ecological determinants.