1. Background

Vesicoureteral reflux (VUR) is the retrograde flow of urine from the bladder into the upper urinary tract (1). It is among the most common urinary tract anomalies in children (2). Primary VUR has been reported in 1% to 10% of children in the United States (3). Meanwhile, in Iran, the prevalence of VUR has been reported to exceed 40% among siblings with a history of urinary reflux (4). The presence of febrile urinary tract infection (UTI) indicates reflux in one-third of affected children (5). In these children, VUR is associated with an increased risk of recurrent pyelonephritis and consequently a higher risk of renal scarring (6). Most children with reflux are asymptomatic but may be at risk for secondary conditions such as acute bladder and kidney infections. In neonates, UTI symptoms may include fever, lethargy, decreased appetite, and sometimes mild diarrhea, whereas older children typically present with dysuria and urinary frequency. In the majority of cases, children with reflux are asymptomatic, and UTI is the most common manifestation of symptomatic reflux (7). A significant risk factor for recurrent UTIs — which can result in renal damage known as reflux nephropathy — is one of the leading causes of chronic renal failure in children (8, 9). Therefore, preventing UTIs in patients with VUR is critically important to avoid reflux nephropathy (10). Evidence-based therapeutic approaches for managing VUR depend on several clinical variables, including a history of febrile UTIs, demographic factors such as age and gender, the presence of bladder or bowel dysfunction manifested as voiding disorders, and the grade of reflux (11).

Common interventions for children with reflux include anti-reflux surgery (endoscopic, laparoscopic, or open) and continuous antibiotic prophylaxis (CAP). The goal of CAP is to maintain sterile urine to reduce the risk of recurrent kidney infections (12, 13). In a study by Shiraishi et al., the results indicated that the mean age at diagnosis of VUR was significantly lower in children who developed UTIs during prophylactic treatment compared to those who did not experience infections during prophylaxis. Furthermore, long-term prophylactic antibiotic therapy was identified as a contributing factor in reducing UTI incidence among patients with VUR (14). Similarly, a study conducted by Hidas, entitled "Predictive Factors for Urinary Tract Infection During Antibiotic Prophylaxis in Patients with Primary Vesicoureteral Reflux", reported a reduction in the occurrence of UTIs in patients receiving prophylactic antibiotics (15). Many authors recommend a conservative approach — namely, CAP — as the initial management option in children, reserving surgical intervention for cases in which prophylaxis fails to prevent UTIs. However, considerable controversy and variability remain in the management of VUR (16). Notably, the efficacy of CAP in reducing infections in children has recently been questioned (17). Studies have demonstrated that antibiotic prophylaxis is as effective as surgical treatment in preventing VUR and recurrent urinary infections (18, 19). Nonetheless, some reports indicate that antibiotic prophylaxis may increase the risk of antibiotic-resistant infections (20). Moreover, long-term antibiotic use cannot completely prevent urinary infections or scarring and may be associated with undesirable side effects (21).

Nitrofurantoin, cephalosporins, and trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole are the drugs of choice. There is ongoing debate regarding the use of CAP in patients with grade III VUR without febrile UTI. Some studies recommend CAP for all patients with VUR, while others discourage its use due to limited efficacy in preventing renal damage and the increased risk of antibiotic resistance (22). Surgical treatment is generally preferred for cases of recurrent urinary infections despite CAP, high-grade reflux, low likelihood of spontaneous resolution, or evidence of renal damage (23). Due to the complications associated with VUR, preventing UTIs in these patients is of great importance because of the risk of nephropathy. Typically, oral antibiotics are administered at doses lower than therapeutic levels for prophylaxis. However, prolonged antibiotic use in children is associated with side effects, underscoring the need for careful prescribing strategies. Considering the high prevalence of VUR and its potential complications, appropriate management approaches are essential.

2. Objectives

This study aimed to compare the efficacy of alternate-day versus daily antibiotic administration for medical prophylaxis in children with VUR.

3. Methods

3.1. Study Design and Sample Size

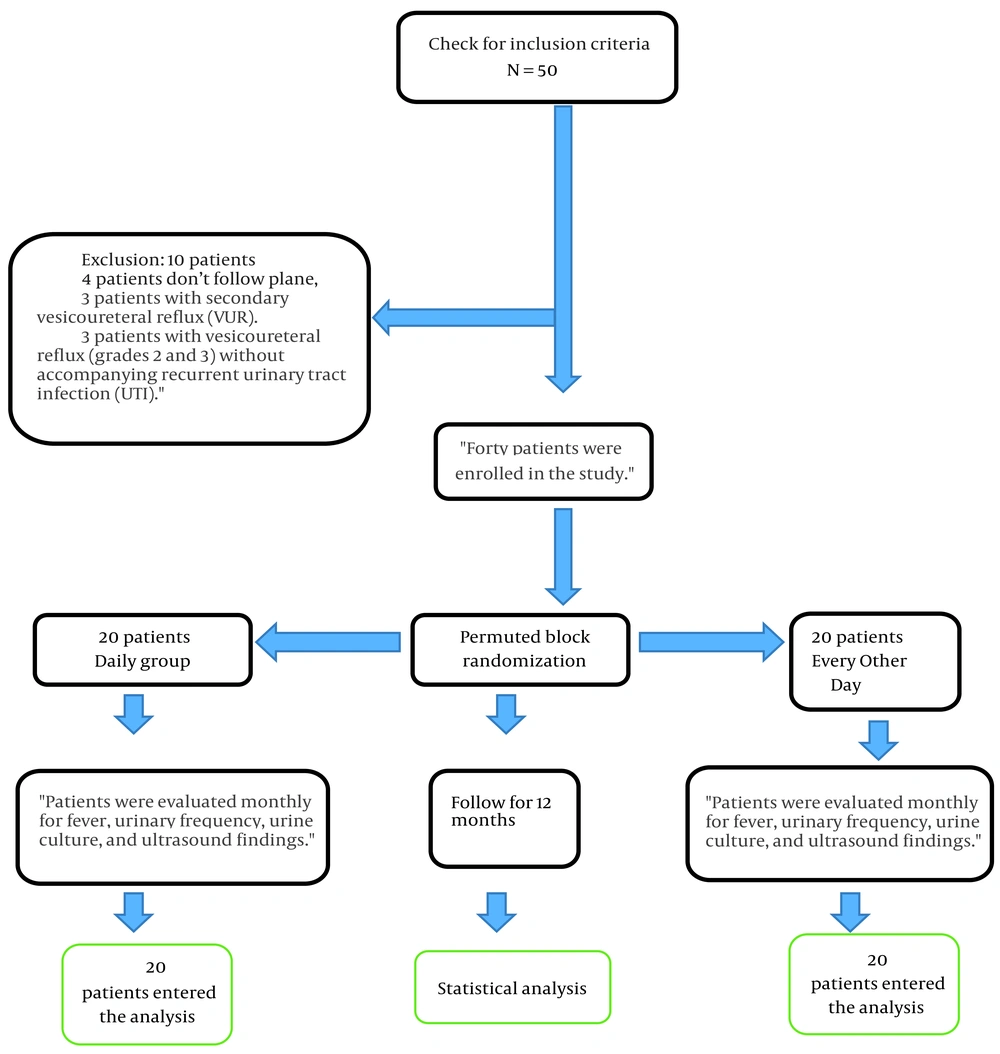

This clinical trial, registered under IRCT number IRCT20250412065295N1 at the Iranian Clinical Trials Center and approved by the Ethics Committee of Shahrekord University of Medical Sciences (ethical code: IR.SKUMS.REC.1403.112), was conducted at Hajar Educational and Therapeutic Center and the nephrology clinics affiliated with Shahrekord University of Medical Sciences, Iran. The study enrolled 40 children diagnosed with primary VUR who presented to these facilities. The sample size was determined using data from a study by Mohajeri et al., which reported an 80% efficacy rate for the intervention in improving fever, pyuria, and urine culture results. With a type I error (α) of 0.05 and a type II error (β) of 0.20, the minimum required sample size was calculated at 14 children per group. To account for a potential 30% dropout rate, the target was increased to 20 participants per group, resulting in a total of 40 children (21). Sampling began purposively, enrolling patients who met the study’s inclusion criteria. Randomization was then carried out using permuted block randomization. Ten blocks, each containing four participants, were generated via random allocation software. Within each block, two participants were assigned to each study group.

3.2. Inclusion Criteria

(1) Children aged 2 months to 15 years with primary VUR grade IV or V; (2) infants under 1 year of age with primary VUR of any grade; (3) children aged 2 months to 15 years with primary VUR of any grade accompanied by recurrent UTIs; (4) children with primary VUR of any grade accompanied by bladder and bowel dysfunction (BBD).

3.3. Exclusion Criteria

Children with secondary VUR, as well as those with grade II or III primary VUR without recurrent UTIs or BBD, were excluded from the study.

3.4. Data Collection Tools

Data were collected using a checklist designed to record each patient’s age, gender, urine culture results, presence of fever, urinary frequency, pyuria status, and ultrasound findings. All checklists were completed by the researcher.

3.5. Study Procedure

After obtaining ethical approval from Shahrekord University of Medical Sciences and securing the necessary permissions, the researcher explained the study objectives in detail to the parents of eligible children. Written informed consent was obtained from all parents prior to enrollment. Based on the defined prophylactic treatment protocol, the type of drug, dosage, and duration of therapy were identical in both groups. In the first group, an oral cephalosporin syrup was administered at a dose of 15 mg/kg every other night for a period of 12 months. In the second group, the same dose was given once daily over the same duration. Aside from this regimen, no additional treatments were provided to either group.

Before initiating prophylactic treatment, all participants underwent renal and urinary tract ultrasonography, as well as urinalysis and urine culture. If symptoms such as fever, dysuria, or urinary frequency developed, urinalysis and culture were performed immediately. In the absence of symptoms, patients proceeded into the study and were evaluated monthly for fever, urinary frequency, pyuria, urine culture results, and ultrasound findings. Data for both groups were documented monthly using a researcher-designed checklist. All laboratory analyses were conducted in a single university-affiliated laboratory.

Parents were thoroughly instructed on correct urine sample collection procedures before providing specimens. The researcher directly supervised the first urine collection for each participant. Temperature measurements were taken by a member of the research team and also using a mercury thermometer for all individuals in the study. All ultrasound examinations were performed by a single radiologist at the same center to ensure consistency. To promote adherence to the medication regimen, parents received detailed training and were asked to record each dose administered on a checklist. The researcher reviewed these records during monthly follow-ups. At the end of the 12-month intervention, clinical and laboratory outcomes for both groups were compared and analyzed statistically.

3.6. Data Analysis

Descriptive statistics were calculated for quantitative variables, including mean ± standard deviation (SD), minimum and maximum values, first and third quartiles, and median. Qualitative variables were summarized as counts and percentages. Statistical analyses were conducted using chi-square tests, Fisher’s exact test, independent t-tests, and paired t-tests. All analyses were performed using SPSS version 20, with a two-sided significance level set at P < 0.05 (Figure 1).

4. Results

The mean age ± SD of the alternate-day (every other night) group was 48.48 ± 36.56 months, compared with 65.31 ± 26.62 months in the daily antibiotic group. Independent t-test analysis revealed no statistically significant difference in mean age between the two groups (Table 1).

| Variable | Every Other Night Group | Daily Group | Independent t-Test |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 48.48 ± 36.56 | 31.65 ± 26.62 | P > 0.1 |

a Values are expressed as mean ± SD.

Based on the results of the study shown in Table 1, there is no statistically significant difference in the mean age between the two groups of antibiotic users taking the medication 'daily' and 'every other night' (P ≥ 0.1). The results indicated that in the daily antibiotic group, two persons (10%) were male, and similarly, in the every-other-night group, two persons (10%) were male, with the remaining participants being female. There was no statistically significant difference between the two groups regarding gender distribution (Table 2).

| Variables | Daily Group | Every Other Night Group | Fisher's Exact Test (P-Value) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | > 0.99 | ||

| Male | 2 (10) | 2 (10) | |

| Female | 18 (90) | 18 (90) | |

| Pyuria | > 0.8 | ||

| Negative | 18 (90) | 19 (95) | |

| Positive | 2 (10) | 1 (5) | |

| Urinary frequency | > 0.8 | ||

| Negative | 18 (90) | 19 (95) | |

| Positive | 2 (10) | 1 (5) | |

| Fever | > 0.23 | ||

| Negative | 17 (85) | 20 (100) | |

| Positive | 3 (15) | 0 (0) | |

| Urine culture | > 0.8 | ||

| Negative | 18 (90) | 19 (95) | |

| Positive | 2 (10) | 1 (5) | |

| Sonographic findings | > 0.47 | ||

| Normal | 18 (90) | 19 (95) | |

| Abnormal | 2 (10) | 1 (5) | |

| Total | 20 (100) | 20 (100) | - |

a Values are expressed as No. (%).

Regarding pyuria, 1 individual (5%) in the daily group and two persons (10%) in the every-other-night group tested positive, while the rest were negative; statistically, no significant difference was observed between the groups (Table 2). For urinary frequency, 1 individual (5%) in the daily group and two persons (10%) in the every-other-night group presented positive symptoms, with the remainder negative, and no statistically significant difference was found between groups (Table 2).

In terms of fever, none of the participants in the daily group reported fever, whereas 3 persons (15%) in the every-other-night group had fever. However, the difference between the groups was not statistically significant (Table 2). Urine culture results showed positivity in 1 individual (5%) of the daily group and two persons (10%) of the every-other-night group, with the rest negative; there was no significant statistical difference between the groups (Table 2).

Regarding sonographic findings, 1 individual (5%) in the daily group and two persons (10%) in the every-other-night group exhibited abnormal ultrasound results, with no statistically significant difference between the groups observed (Table 2).

There was no statistically significant difference in the gender distribution of the study participants between the two groups of antibiotic users receiving the medication 'daily' and 'every other night' (P ≥ 0.99). Similarly, no significant differences were observed in pyuria, urinary frequency, and urine culture (P > 0.8), fever (P > 0.23), or sonographic findings (P > 0.47).

5. Discussion

The present study aimed to conduct a comparative evaluation of the effectiveness of antibiotic prophylaxis administered every other day versus daily in children with VUR. The results showed no statistically significant differences between the two groups (daily vs. alternate-day antibiotic administration) in terms of mean age or gender distribution. Several studies have examined the relationship between age, gender, and the occurrence and treatment of VUR. According to Skoog et al., VUR is more prevalent in infant boys, whereas older children show a significantly higher incidence among girls — a finding consistent with the present study. Both groups exhibited a relatively balanced gender distribution, though a higher prevalence was observed among girls, aligning with the typical epidemiological pattern of VUR (24).

In a 2008 systematic review by Williams et al. on studies of VUR in children, it was found that the average age of affected patients typically falls between 1 and 5 years. Age was identified as a key factor influencing the likelihood of spontaneous resolution of VUR. The present study, with a similar average age across both groups, falls within this same range, indicating that the study population reflects the common age bracket for VUR onset (25). This is particularly important because age also affects the response to prophylactic treatment. For instance, Blumenthal’s 2006 study reported that children under the age of two are more likely to respond favorably to prophylactic therapy (26).

Regarding gender, Silva et al. studied over 600 children with VUR and found that gender did not significantly influence treatment outcomes. However, UTIs were more common among girls. These findings are consistent with the present study, which also showed no significant gender-based differences between the intervention groups, despite a higher proportion of female participants (27). The importance of prophylactic treatment for urinary reflux in relation to age and gender has been highlighted in several studies. Chand et al. examined the impact of these factors on the progression of VUR and concluded that, although age and gender do not directly influence the development of renal scarring, they may play a role in guiding treatment decisions (28).

The results showed no significant difference between the two groups — daily versus alternate-day antibiotic therapy — in the incidence of clinical symptoms such as fever. These findings suggest that both dosing regimens were equally effective in preventing fever, a conclusion supported by other studies. For instance, Tullus reported that prophylactic antibiotic treatment in children with VUR did not significantly reduce fever associated with UTIs (29). This may be attributed to the multifactorial nature of fever in this population, including underlying conditions such as renal dysfunction or chronic kidney inflammation. Hensle et al. noted that the effectiveness of antibiotics in reducing VUR-related fever depends on the severity of UTIs and the presence of kidney damage. While antibiotics may be effective in treating acute infections, their therapeutic impact is limited in cases of chronic inflammation or reflux-induced fever (30). The present findings support this view, suggesting that fever in such cases is more likely due to chronic renal inflammation rather than acute infection, and therefore may not require additional antibiotic treatment.

Urinary frequency is a common symptom in children with VUR — likely resulting from recurrent UTIs, inflammation, or elevated intravesical pressure due to reflux — yet the findings indicated no significant difference in its occurrence between the two antibiotic regimens. Similarly, Peters and Rushton reported that prophylactic antibiotics frequently fail to alleviate urinary frequency in children with VUR (31). Craig et al. found that while antibiotic therapy effectively controlled UTIs in children with VUR, it did not significantly reduce urinary frequency compared to control groups (32). Therefore, additional antibiotic use may not influence urinary frequency in VUR patients, as this symptom likely arises from non-infectious biological factors not directly affected by antibiotics.

No significant difference in pyuria (the presence of white blood cells in urine) was observed between the two groups. Pyuria, typically indicative of a UTI, may not be prevented by prophylactic antibiotics, particularly in children without a history of recurrent UTIs, as noted by Shaikh et al. (33). Hari et al. emphasized that pyuria in children with VUR may not result solely from UTI but may also arise from bladder inflammation or irritation caused by reflux; in such cases, antibiotics may not effectively reduce pyuria (34). Consequently, limiting antibiotic prophylaxis in patients with VUR is a key finding of this clinical trial.

The results also showed no significant difference in ultrasound findings between the two groups, indicating that prophylactic antibiotics did not substantially improve kidney or urinary tract structure. Multiple studies have reported similar results. For example, Hari and Meena observed no difference in renal damage between children who received prophylactic antibiotics and those who did not, suggesting that long-term antibiotic use does not prevent structural kidney damage in VUR (35).

No significant difference in UTI incidence was found between the daily and alternate-day antibiotic groups. One of the primary goals of prophylactic antibiotics in children with VUR is to prevent UTIs; however, the present study found no significant difference in incidence between the two dosing regimens. This finding aligns with Elder et al., who reported that prophylactic antibiotics in children with grades 1 - 3 VUR did not significantly prevent UTIs (36). Similarly, Shaikh et al. noted that prophylactic antibiotics may be ineffective in low-grade VUR (grades 1 - 3), particularly in cases without significant structural abnormalities. For children with higher-grade VUR (grades 4 - 5), who are at greater risk of kidney damage, prophylactic antibiotics were expected to be more effective. Nevertheless, no significant difference in UTI incidence was observed between the two antibiotic regimens in this study (33).

Rossleigh found that both daily and intermittent antibiotic regimens were effective in controlling UTIs in children with VUR, although intermittent dosing reduced side effects such as antibiotic resistance (37). Goneau et al. also highlighted that long-term antibiotic use can increase microbial resistance and reduce treatment efficacy (38). The lack of significant differences between the two groups (daily vs. alternate-day antibiotics) in the present study may therefore be related to issues such as microbial resistance and adverse effects. These results suggest that neither dosing regimen significantly reduced UTIs or improved clinical symptoms in children with VUR. Consequently, reducing antibiotic use may help minimize drug resistance and side effects. Antibiotic resistance and the potential harms of long-term therapy should be considered key factors when determining prophylactic strategies for patients with VUR.

5.1. Conclusions

This study demonstrated that prophylactic antibiotic administration, whether daily or intermittent (every other day), did not significantly reduce the incidence of UTIs or improve clinical symptoms in children with VUR. Therefore, less frequent antibiotic use may help limit the development of drug resistance and minimize antibiotic-related side effects. Antibiotic resistance and the adverse effects associated with long-term therapy should be considered key factors when determining prophylactic treatment strategies for patients with VUR.

5.2. Study Limitation

Limited family cooperation with the research team and low health literacy within the study population were among the key challenges encountered during the research. These limitations were mitigated through comprehensive explanation and active engagement by the research team. Additionally, the study did not account for the socioeconomic status of the parents, which may have influenced the outcomes. It is recommended that future research consider this variable to enhance the validity of findings.

5.3. Clinical Application

The primary clinical finding of this study is that reduced antibiotic usage plays a key role in decreasing drug resistance and minimizing side effects in patients with urinary reflux undergoing prophylactic treatment.