1. Background

Acetaminophen overdose can cause direct nephrotoxicity in addition to its well-established hepatotoxic effects. Within the kidney, a portion of acetaminophen metabolism occurs through the cytochrome P-450 enzyme system, particularly the CYP2E1 isoform, as well as prostaglandin synthetase and N-deacetylase enzymes. These pathways generate the highly reactive metabolite N-acetyl-p-benzoquinone imine (NAPQI) and other toxic intermediates. Under normal physiological conditions, NAPQI is detoxified by conjugation with glutathione (GSH). However, in overdose situations, renal GSH reserves are depleted, leading to insufficient detoxification and excessive accumulation of reactive intermediates. The NAPQI covalently binds to sulfhydryl groups of cellular proteins, forming toxic adducts that disrupt the structural and functional integrity of renal tubular cells. This process induces severe oxidative stress through the excessive generation of reactive oxygen species (ROS), which promote lipid peroxidation, membrane disruption, and organelle damage. At the mitochondrial level, oxidative stress and protein adduct formation trigger mitochondrial dysfunction and the release of cytochrome c. This event activates the intrinsic apoptotic pathway, characterized by upregulation of Bax and activation of caspase-3, culminating in programmed cell death of tubular epithelial cells. In parallel, uncontrolled injury results in necrosis of tubular structures. Moreover, oxidative stress and cellular injury act as upstream regulators of inflammation by activating transcription factors such as NF-κB, which enhance the expression of proinflammatory cytokines, including TNF-α and IL-6. Fibrotic mediators such as TGF-β1 are also upregulated, exacerbating structural damage and promoting renal dysfunction. Collectively, the nephrotoxic mechanism of acetaminophen involves three interrelated processes: (1) Oxidative stress due to GSH depletion and ROS overproduction, (2) activation of apoptotic pathways via mitochondrial dysfunction and caspase signaling, and (3) inflammatory and fibrotic responses mediated by NF-κB, TNF-α, IL-6, and TGF-β1. These events ultimately result in tubular necrosis and impairment of glomerular filtration (1).

In various experimental and clinical studies, acetaminophen-induced nephrotoxicity has been consistently reported. Animal studies demonstrated that acetaminophen overdose causes tubular necrosis, oxidative stress, inflammation, and apoptosis, with alterations in renal antioxidant defenses such as GSH, superoxide dismutase (SOD), and glutathione peroxidase (GPx) (1, 2). Some studies also highlighted the enhancement of protective proteins, such as aquaporin-1 to mitigate injury (2). Clinical reports and reviews confirm that acute severe acetaminophen poisoning can result in acute kidney injury, even in adolescents, with manifestations ranging from elevated serum creatinine and urea to structural tubular damage (3-5). Mechanistic investigations emphasize that mitochondrial ROS production plays a central role, promoting mitochondrial dysfunction, apoptosis, and inflammatory responses in renal tissue (6, 7). Collectively, these studies underscore that oxidative stress, apoptotic signaling, and inflammation are key mediators of acetaminophen-induced kidney injury. Considering the mechanisms of kidney damage, several studies have investigated the effects of natural compounds with antioxidant and anti-inflammatory properties. The results show that compounds such as thymoquinone, curcumin, and alpha-lipoic acid can exert significant protective effects against acetaminophen-induced nephrotoxicity by inhibiting inflammation, regulating apoptosis pathways, and enhancing the antioxidant system (1). Similarly, celastrol, a plant compound with antioxidant and anti-inflammatory properties, has been shown to inhibit acetaminophen-induced kidney injury in animal models by reducing markers of kidney injury such as BUN, creatinine, TNF-α, IL-6, Bax, and caspase-3, as well as increasing the activities of antioxidant enzymes SOD, catalase (CAT), GSH, nuclear transcription factor erythroid-related 2 (Nrf2), and heme oxygenase-1 (HO-1) (2).

This multi-targeted approach, addressing both oxidative stress and inflammation, underlies the protective effects of natural compounds against drug-induced organ injury. Karimi-Dehkordi et al. showed that Dracocephalum kotschyi extract protected the liver by reducing oxidative stress and inhibiting inflammatory mediators (8). Similarly, Yazdani et al. reported hepatoprotection by chlorogenic acid (9), Riazi et al. highlighted the antioxidant effects of chia seeds (10), and Rezvan and Saghaei demonstrated the anti-inflammatory activity of D. kotschyi in post-surgical adhesions (11). Together, these studies confirm that targeting oxidative stress and inflammation is an effective strategy against drug- and toxin-induced organ damage. Feselol is a sesquiterpene coumarin extracted from plants of the genus Ferula, especially the species F. vesceritensis. Oughlissi-Dehak et al. identified this compound along with other sesquiterpenes in the aerial parts of F. vesceritensis using chromatographic and spectroscopic methods (12). The findings of Abdel-Kader et al. also confirmed these results (13). These compounds are known as terpenoid coumarins, which have diverse biological activities such as antioxidant and anti-inflammatory effects and can inhibit NO-synthase in cell models, meaning they reduce the activity of the enzyme that causes the production of harmful nitric oxide and inflammation in cells, thus preventing cellular damage (14). Studies have shown that similar coumarins in different Ferula species have a significant ability to inhibit inflammatory pathways in RAW 264.7 cells. RAW 264.7 cells, a mouse-derived macrophage cell line, are widely used in the laboratory to study immune responses and inflammation (15). These compounds inhibit the inflammatory response by reducing the expression of inflammatory cytokines, TNF-α and IL-6, in these cells and exhibit effective anti-inflammatory effects. The biological properties of feselol are probably due to the presence of a special structure called "saturated alpha-beta" in its sesquiterpene section. This structure provides greater stability to the compound and its anti-inflammatory and antioxidant activities (14, 16). These properties make feselol and its similar compounds potential options for reducing inflammation in various diseases, including drug-induced kidney damage. Because acetaminophen-induced renal injury is caused by oxidative stress, inflammation, and cellular apoptosis, it is expected that feselol, with its antioxidant and anti-inflammatory effects, regulates the production pathways of apoptosis-promoting molecules such as Bax and caspase-3, and also affects the expression of anti-apoptotic genes such as Bcl-2. Therefore, feselol could be a suitable candidate for preventing acetaminophen-induced renal toxicity.

2. Objectives

In this study, the protective effects of feselol against acetaminophen-induced nephrotoxicity in mice were investigated by evaluating oxidative stress markers, apoptotic gene expression, and renal inflammatory factors, and its efficacy was compared with the standard antidote, N-acetylcysteine (NAC).

3. Methods

3.1. Materials

Acetaminophen ampoules were obtained from Alborzdarou Company (Iran), and NAC ampoules were obtained from Exir Company (Iran). Additionally, feselol powder was obtained from Gol Eksir Pars Company (Iran). Tween 80 (Sigma-Aldrich, Germany) was used in this study. The kits used in this study [SOD, GPx, CAT, and malondialdehyde (MDA)] were all purchased from Kiazist Company (Iran). RNA extraction (CAT Nos. A101231) and Complementary DNA (cDNA) synthesis kit (CAT Nos. A101162) were purchased from Parstous Company (Iran). Also, SYBR Green Master Mix (RealQ Plus 2x Master Mix Green, CAT. Nos. A325402) was purchased from Amplicon (Denmark).

3.2. Experimental Animals

In this study, 42 male Balb/c mice weighing approximately 25 ± 2 g were used. The animals were obtained from the Laboratory Animal Center and allowed to acclimate for 7 days under controlled conditions (temperature: 22 ± 2°C, 12:12 h light/dark cycle) with ad libitum access to standard chow and drinking water. All experimental procedures were conducted in accordance with the ethical principles of the university bioethics committee and approved protocol (IR.IAU.SHK.REC.1403.381).

3.3. Study Design

Mice were randomly assigned to seven groups (n = 6) to reduce selection bias, and investigators were blinded during data collection. The sample size was chosen based on previous studies in similar animal models and expected effect sizes, which ensures sufficient statistical power for detecting differences between groups.

- Group 1 (control): Received 0.1 mL of normal saline intraperitoneally (IP) daily.

- Group 2 (acetaminophen): Received 0.1 mL of normal saline for two days and acetaminophen (400 mg/kg, IP) on day 3.

- Group 3 (feselol 25 + acetaminophen): Administered feselol (25 mg/kg, IP) for three days; two hours after the last dose, acetaminophen was injected.

- Group 4 (feselol 50 + acetaminophen): Similar to group 3, except feselol was administered at 50 mg/kg.

- Group 5 (NAC+acetaminophen): Administered NAC (300 mg/kg, IP) for three days; two hours after the last dose, acetaminophen was injected.

- Group 6 (Tween 80 + Acetaminophen): Received Tween 80, as feselol vehicle (0.1 mL, IP) for three days; two hours after the last dose, acetaminophen was injected.

- Group 7 (feselol 50 only): Received feselol (50 mg/kg, IP) for three days to assess its safety.

The study duration was three days, which is appropriate for assessing the acute effects of acetaminophen-induced nephrotoxicity and the potential protective effects of feselol in this animal model. End-point measurements were performed 24 hours after the final injection.

3.4. Sampling and Tissue Preparation

Twenty-four hours after the final injection, the animals were sacrificed under deep anesthesia (Ketamine 90 mg/kg and Xylazine 4 mg/kg). Kidneys were excised; and frozen in Eppendorf tubes for RNA extraction and gene expression analysis.

3.5. Evaluation of Oxidative Stress Markers in Renal Tissue

Oxidative stress markers were measured in kidney tissue homogenates following the manufacturer’s instructions. Briefly, a portion of the kidney tissue was homogenized in cold phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and centrifuged at 10,000 × g for 15 minutes at 4°C. The supernatant was collected and used for the measurement of the following.

- Lipid peroxidation was evaluated by measuring MDA levels using the thiobarbituric acid reactive substances (TBARS) method, and the results were expressed as nmol MDA per mg of protein.

- The SOD activity was determined using a spectrophotometric method based on the inhibition of autoxidation of pyrogallol, and the results were expressed as units per mg of protein (U/mg protein).

- The CAT activity was assayed by monitoring the decomposition of hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) at 240 nm, and the results were expressed as µmol of H2O2 consumed per minute per mg of protein (µmol H2O2 consumed/min/mg protein).

- The GPx activity was measured by quantifying the oxidation of NADPH at 340 nm in the presence of GSH reductase and reduced GSH, and the results were expressed as nmol of NADPH oxidized per minute per mg of protein (nmol NADPH oxidized/min/mg protein).

For the evaluation of oxidative stress markers in renal tissue, the total protein content of the homogenates was determined by the Bradford method to normalize the enzymatic activities (8).

3.6. Evaluation of Inflammatory and Apoptotic Gene Expression by Real-time PCR

Total RNA was extracted from kidney tissues using a commercial RNA isolation kit according to the manufacturer's instructions. The concentration and purity of the extracted RNA were determined spectrophotometrically. The cDNA was synthesized from 1 µg of total RNA using a reverse transcriptase enzyme. The expression levels of the inflammatory factors IL-1β and TNF-α, and the anti-inflammatory cytokine Interleukin-10 (IL-10), as well as the pro-apoptotic genes caspase-3 and Bax, along with the anti-apoptotic gene Bcl-2, were quantified by RT-PCR using specific primers (Table 1) and a SYBR Green master mix. The amplification reactions were performed in triplicate. The GAPDH gene was used as an internal reference (housekeeping) control to normalize the expression data. The relative gene expression was calculated using the 2-ΔΔCT method (8).

| Gene Names | Primer Sequence 5ˈ to 3ˈ |

|---|---|

| TNF-α-F | GCCTCTTCTCATTCCTGCTTGTG |

| TNF-α-R | GTTTGCTACGACGTGGGCTACAG |

| IL1-β-F | GTGGCAGCTACCTGTGTCTT |

| IL1-β-R | CTCTGCTTGTGAGGTGCTGA |

| IL10-F | CCAGTTTTACCTGGTAGAAGTGATG |

| IL10-R | TGTCTAGGTCCTGGAGTCCAGCAGACTC |

| Bax-F | TTGCTACAGGGTTTCATCCAGG |

| Bax-R | CAGCTTCTTGGTGGACGCATC |

| Caspase-3-F | GTCATCTCGCTCTGGTACGG |

| Caspase-3-R | GTGGAAAGTGGAGTCCAGGG |

| Bcl-2-F | TACGAGTGGGATGCTGGAGA |

| Bcl-2-R | TCAAACAGAGGTCGCATGCT |

| GAPDH-F | CTTCTCCTGCAGCCTCGT |

| GAPDH-R | ACTGTGCCGTTGAATTTGCC |

3.7. Statistical Analysis

Data are expressed as mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM). Statistical differences among groups were analyzed using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by Tukey’s post-hoc test. A P-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Data analysis was performed using SPSS software.

4. Results

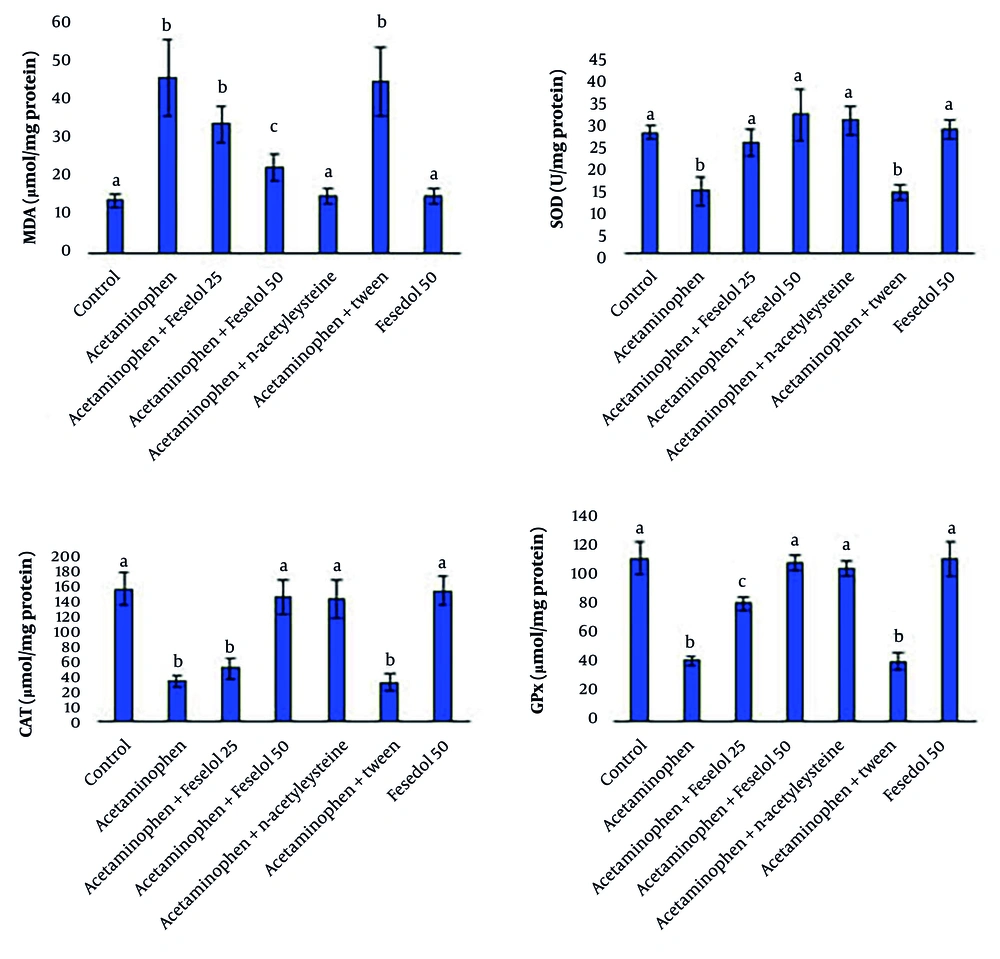

4.1. Oxidative Stress Markers in Renal Tissue

Acetaminophen administration caused significant oxidative stress in the tissue. This effect was observed with a significant increase in MDA (an indicator of lipid peroxidation damage) and a significant decrease in the activities of antioxidant enzymes, including SOD, CAT, and GPx, compared to the control group. Co-administration of 25 and 50 mg/kg of feselol with acetaminophen showed dose-dependent protective effects (except for SOD). Twenty-five mg of feselol did not significantly change MDA and CAT compared to the acetaminophen group, while 50 mg caused a significant decrease in MDA and a significant increase in CAT. However, even 50 mg of feselol failed to restore MDA levels to control levels, but CAT activity returned to normal levels. In the case of SOD, both 25 and 50 mg doses had a similar effect in increasing it and restored SOD activity to control levels. Also, feselol dose-dependently increased GPx significantly compared to the acetaminophen group, although the 50 mg dose failed to restore GPx to control levels. These results indicate that the higher dose of feselol is very effective in neutralizing the oxidative stress induced by acetaminophen.

The NAC, as the standard treatment, showed potent protective effects. It significantly reduced MDA levels and increased the activities of SOD, CAT, and GPx enzymes, returning them to normal levels. Feselol at the higher dose (50 mg/kg) showed similar antioxidant effects to NAC in restoring CAT, SOD, and GPx activities; however, NAC was more potent in reducing MDA levels and restoring them to control levels (Figure 1).

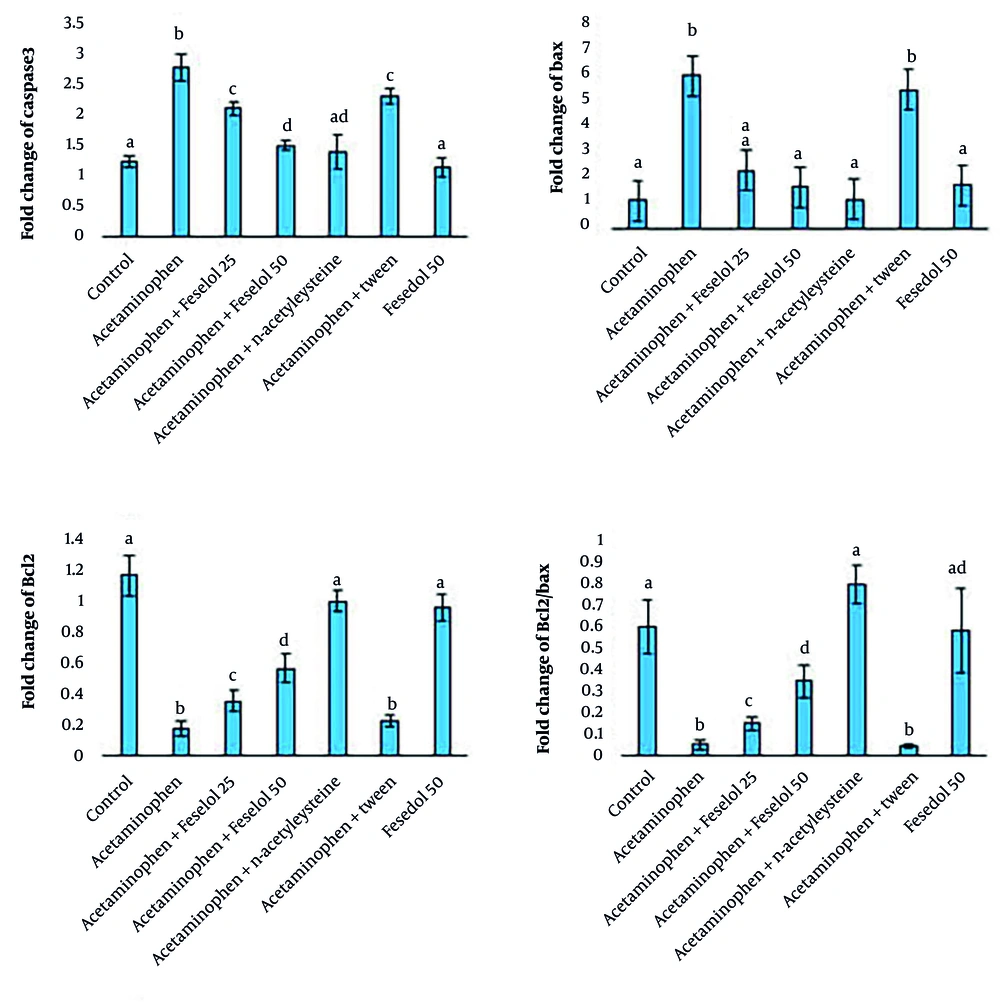

4.2. Gene Expression of Apoptosis-Related Markers in Renal Tissue

Acetaminophen administration significantly increased the expression of caspase-3 and Bax and decreased Bcl-2, and the Bcl-2/Bax ratio compared to the control group. Treatment with feselol at doses of 25 and 50 mg/kg led to a dose-dependent reduction in caspase-3 expression compared to the acetaminophen group, although levels did not return to normal. Both doses of feselol significantly reduced Bax expression to within the normal range. Additionally, feselol treatment caused a dose-dependent increase in Bcl-2 expression compared to the acetaminophen group, but levels remained below normal. The Bcl-2/Bax ratio was also significantly and dose-dependently increased by feselol administration. In the NAC group, treatment significantly decreased caspase-3 and Bax expression and increased Bcl-2 expression and the Bcl-2/Bax ratio compared to the acetaminophen group, restoring these parameters to normal levels. Comparative analysis of the protective effects of NAC and feselol revealed that high-dose feselol (50 mg/kg) exhibited similar efficacy to NAC in reducing caspase-3 and Bax expression. However, NAC provided more pronounced protective effects on Bcl-2 expression and the Bcl-2/Bax ratio, restoring these parameters to normal levels. The Bcl-2/Bax ratio is an important indicator in assessing the balance between anti-apoptotic proteins (Bcl-2) and apoptosis-inducing proteins (Bax). This ratio plays a key role in the regulation of apoptosis or programmed cell death. A decrease in this ratio indicates an increase in the apoptotic process, and an increase indicates a decrease in cell death (Figure 2).

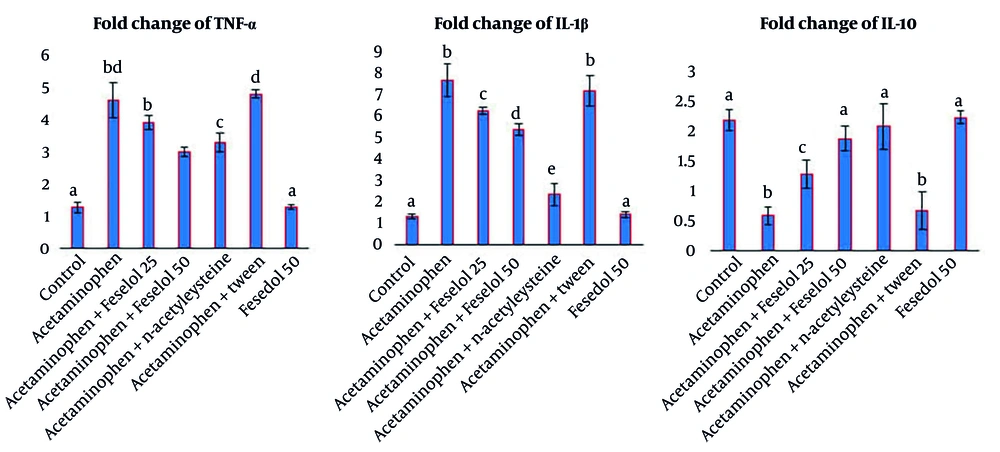

4.3. Gene Expression of Inflammatory Cytokines in Renal Tissue

Acetaminophen administration significantly increased TNF-α and IL-1β expression and significantly decreased IL-10 expression compared to the control group. Administration of 25 and 50 mg/kg of feselol with acetaminophen resulted in a dose-dependent decrease in TNF-α and IL-1β, with the higher dose having a greater protective effect. Both doses of feselol significantly and dose-dependently increased IL-10 expression compared to the acetaminophen group. The NAC significantly decreased TNF-α and IL-1β expression and increased IL-10 expression compared to the acetaminophen group, and only restored IL-1β to normal levels. Fifty mg/kg of feselol had a similar effect to NAC in reducing TNF-α and increasing IL-10. The NAC showed a greater protective effect in reducing IL-1β than feselol and restored the level of this cytokine to the normal range (Figure 3).

Administration of Tween with acetaminophen did not show significant differences in all parameters compared to the acetaminophen group, indicating that Tween, as a feselol solvent, did not interfere with the test results. Also, the results of the feselol 50 group did not show significant differences in all parameters compared to the control group, indicating that feselol does not have inflammatory, apoptotic, or oxidative effects.

5. Discussion

In this study, we investigated the protective effects of feselol, a sesquiterpene coumarin isolated from Ferula species, on the regulation of apoptotic gene expression, inflammatory mediators, and oxidative stress parameters in the kidneys of mice with acetaminophen-induced nephrotoxicity. As expected, acetaminophen administration induced severe oxidative stress, marked by a significant increase in MDA, a key marker of lipid peroxidation, along with a depletion in the activities of crucial antioxidant enzymes, SOD, CAT, and GPx. This observation is consistent with the established model of acetaminophen nephrotoxicity, wherein the toxic metabolite NAPQI depletes GSH, the cell's primary antioxidant defense system, leading to an accumulation of ROS, mitochondrial damage, and subsequent cellular dysfunction (4, 5). Notably, mitochondrial dysfunction — identified as a critical driver of oxidative stress and inflammation in ischemic acute kidney injury — appears to be a central mechanism in acetaminophen toxicity as well (7). In parallel, acetaminophen exposure markedly upregulated the pro-apoptotic genes caspase-3 and Bax while downregulating the anti-apoptotic gene Bcl-2, leading to a decreased Bcl-2/Bax ratio, activation of apoptotic pathways, and extensive renal cellular injury. Concurrently, acetaminophen significantly elevated pro-inflammatory cytokines (IL-1β and TNF-α) and suppressed the anti-inflammatory cytokine IL-10, highlighting the induction of inflammatory responses. These findings show that, besides its known liver toxicity, acetaminophen can directly cause acute kidney injury in our animal model via oxidative stress, inflammation, and apoptosis. As described by Moshaie-Nezhad et al., acetaminophen-induced nephrotoxicity is a proven side effect of its overdose, in which multiple mechanisms are involved (17).

Acetaminophen-induced nephrotoxicity occurs when its toxic metabolite, NAPQI, is produced during metabolism in the liver and kidney. The NAPQI depletes GSH, causing oxidative stress and the accumulation of ROS, which leads to lipid peroxidation and cellular damage. This results in mitochondrial dysfunction and triggers both apoptotic and necrotic cell death in renal tissue. The damage is further worsened by the activation of inflammatory cytokines (TNF-α, IL-1β) and apoptotic pathways (Bax, caspase-3). The imbalance between pro- and anti-apoptotic proteins leads to extensive tissue destruction (17). Research across multiple disease models, including human cancers, demonstrates that the coordinated modulation of oxidative stress and apoptotic pathways constitutes a fundamental mechanism underlying cellular injury, as exemplified by the role of microRNAs such as miR-372 in regulating these processes (18). Co-treatment with feselol demonstrated dose-dependent protective effects, significantly mitigating this multifaceted insult. The higher dose of feselol (50 mg/kg) markedly reduced MDA levels and restored the activities of SOD, CAT, and GPx to levels comparable to the control group. This potent antioxidant activity was accompanied by the downregulation of apoptotic genes (caspase-3, Bax), restoration of the Bcl-2/Bax ratio, suppression of pro-inflammatory cytokines (TNF-α, IL-1β), and elevation of IL-10. These findings are consistent with previous reports confirming the antioxidant and anti-inflammatory properties of sesquiterpene coumarins from Ferula species (14, 19). The protective effects of feselol may be related to its α,β-saturated sesquiterpene structure; however, this attribution remains speculative, as our study did not directly investigate structure-activity relationships. Previous studies have reported that such structural features in Ferula-derived coumarins contribute to antioxidant and anti-inflammatory properties (19, 20). Therefore, while our findings demonstrate feselol’s antioxidant, anti-apoptotic, and anti-inflammatory effects in vivo, the precise structural basis underlying these effects should be explored in future studies.

Several studies have confirmed that these compounds downregulate pro-inflammatory cytokines, inhibit radical-generating enzymes, and mitigate oxidative and inflammatory responses (19, 21). Moreover, their anti-apoptotic activities have been demonstrated in vitro, promoting cellular survival and tissue protection. Similarly, Ghasemi et al. reviewed the anti-inflammatory, antioxidant, and immunomodulatory properties of Ferula species, highlighting their potential to regulate apoptosis and inflammation in animal models (20). Together, these findings provide strong scientific evidence supporting the therapeutic potential of sesquiterpene coumarins as natural protective agents against drug-induced toxicity. Feselol's efficacy was similar to the standard drug NAC, which also significantly attenuated acetaminophen-induced injury by reducing oxidative stress, modulating apoptotic gene expression, and restoring cytokine balance. This observation is further supported by contemporary literature validating NAC's efficacy in various nephrotoxicity models. Kocamuftuoglu et al. documented NAC's ability to improve renal functional parameters (reduced serum urea and creatinine), ameliorate histological damage, and attenuate oxidative stress, though noting diminished efficacy in combination with cyclosporine A (22). Similarly, Sallam et al. demonstrated NAC's capacity to suppress apoptotic signaling pathways (reduced Bax and caspase-3 expression), decrease pro-inflammatory mediators (TNF-α), and enhance antioxidant defenses through GSH elevation, thereby counteracting drug-induced renal apoptosis and inflammation (23).

The remarkable similarity in mechanistic profiles between feselol and NAC — particularly their shared antioxidant, anti-apoptotic, and anti-inflammatory properties — suggests feselol's potential as either a natural alternative or complementary therapeutic approach to NAC in managing drug-induced nephrotoxicity. The concordance of our findings with established literature on NAC's protective mechanisms reinforces the validity of feselol's observed renoprotective effects. The potent antioxidant activity of feselol likely underpins its broader protective mechanism, as the amelioration of oxidative stress directly prevents the activation of downstream inflammatory and apoptotic pathways. This finding aligns with a recent study by Sedghi et al., which demonstrated that oleuropein, another natural phenolic compound, attenuated acetaminophen overdose-induced kidney injury by enhancing the antioxidant defense system (6). Therefore, the capacity of feselol to directly neutralize oxidative stress reinforces its pivotal role in modulating inflammation and apoptosis, ultimately preserving renal tissue architecture and function against acetaminophen-induced insult.

5.1. Conclusions

Overall, our findings in this animal model suggest that feselol could potentially act as a natural protective agent against acetaminophen-induced nephrotoxicity by attenuating oxidative stress, modulating apoptotic gene expression, and suppressing inflammatory responses. These data provide one of the first in vivo indications of the possible renoprotective effects of feselol in mice, and its comparable efficacy to NAC highlights it as a promising natural candidate. However, since the present study was conducted in a short-term model of acute toxicity, these findings should be interpreted with caution and not directly extrapolated to humans. Further investigations using different doses, longer treatment durations, and additional experimental models are warranted to further explore and validate these potential effects toward clinical applications.