1. Background

Methotrexate (MTX), a folate antagonist with potent antimetabolite and cytotoxic properties, remains a foundational therapeutic agent across a broad spectrum of malignant and autoimmune disorders. Its clinical utility is firmly established in the management of acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL), non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL), rheumatoid arthritis, and psoriasis, underscoring its indispensable role in contemporary oncology and immunomodulatory therapy (1, 2).

In the United States, MTX is prescribed to more than one million individuals each year for rheumatoid arthritis alone, with approximately 20 - 30% of these patients developing elevations in hepatic transaminases during treatment (3). On a global scale, MTX-induced hepatotoxicity constitutes an estimated 10 - 15% of all drug-induced liver injury (DILI) cases, a burden that is disproportionately greater among patients with pre-existing hepatic vulnerability, including those with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) (3, 4). The risk of hepatic injury is strongly dose-dependent; high-dose MTX (HD-MTX) protocols exceeding 500 mg/m² are associated with a 20 - 30% incidence of acute hepatocellular damage, particularly in pediatric and adolescent populations receiving therapy for ALL or osteosarcoma (5). These epidemiological patterns highlight the pressing need for effective hepatoprotective strategies to mitigate MTX-related liver injury and enhance therapeutic safety. Chronic low-dose MTX therapy, commonly used in rheumatoid arthritis and psoriasis, has been linked to liver fibrosis in 5-10% of patients, although recent studies suggest that the cumulative dose of MTX may not be the sole predictor of fibrosis progression (6, 7). Notably, patients with NAFLD, which affects approximately 25% of the global population, are at a significantly higher risk of MTX-induced liver injury, with studies indicating a 2- to 3-fold increase in hepatotoxicity compared to patients without NAFLD (5, 8, 9).

Despite its therapeutic efficacy, the clinical utility of MTX is often limited by its dose-dependent hepatotoxicity, which manifests as elevated liver enzymes, oxidative stress (OS), and inflammatory damage (10, 11). Hepatotoxicity emerges as a significant challenge in the long-term management of conditions necessitating MTX therapy, emphasizing the urgent need for interventions to mitigate this adverse effect. Hepatotoxicity associated with MTX primarily manifests following chronic administration of high doses (12, 13). The hepatotoxic effects of MTX are primarily mediated through the overproduction of ROS, which disrupts the redox balance within hepatocytes. ROS, including hydrogen peroxide (H₂O₂), hydroxyl radicals (OH•), and superoxide anions (O₂⁻), are cellular metabolism byproducts that, in excess, overwhelm the endogenous antioxidant systems, resulting in the depletion of mitochondrial non-enzymatic and enzymatic antioxidant defense systems (14, 15). Moreover, administration of MTX has been shown to decrease the availability of nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate (NADPH) under normal physiological conditions (16-18). Nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate is crucial for maintaining the reduced state of cellular glutathione (GSH), a vital cytosolic antioxidant that protects against ROS-mediated damage (17, 19). In addition to OS, MTX-related hepatotoxicity is characterized by the activation of pro-inflammatory pathways. Methotrexate upregulates the expression of interleukin-6 (IL-6), tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α), and IL-1β, pro-inflammatory cytokines that contribute to hepatic inflammation and tissue injury (20). They activate nuclear factor-kappa B (NF-κB), amplifying the inflammatory reaction by promoting the expression of genes that contribute to apoptosis and inflammation (21-23). Thus, exploring natural, non-toxic antioxidant agents as potential adjuvants to mitigate MTX-induced hepatotoxicity has been considered (15, 24).

Arbutin, a glycosylated hydroquinone, is a promising natural compound with potent anti-inflammatory and antioxidant effects. Found in plants such as Arctostaphylos uva-ursi and various Pyrus species, ARB has been shown to mitigate OS by upregulating antioxidant enzymes, including GSH, catalase (CAT), superoxide dismutase (SOD), and GPx, and scavenging free radicals (25-27). Its presence has been detected in measurable amounts in the peduncles, leaves, and bark of various Pyrus species (25). Arbutin is a yellow powder that is soluble in water and alcohols, with a molecular weight of 272.25 g/mol. The absorbance spectrum of ARB shows peaks at 240 nm and 267 nm, which represent the minimum and maximum wavelengths, respectively (28). Methotrexate-induced hepatotoxicity results from the accumulation of reactive oxygen species and increased inflammatory signaling, leading to a cycle of liver cell injury. This situation underscores the need for interventions that can restore redox balance and alleviate inflammation. Arbutin, known for enhancing antioxidant defenses and suppressing inflammatory mediators, may help disrupt these harmful processes. We investigated whether pretreatment with ARB can reduce MTX-induced liver injury by minimizing oxidative stress, preserving antioxidant capacity, and modulating key inflammatory pathways in hepatocytes.

2. Objectives

This study investigated the hepatoprotective effects of ARB in a rat model of MTX-induced liver damage. By administering ARB at doses of 25, 50, and 100 mg/kg, we assessed its ability to reduce liver injury through serum liver enzyme activity, oxidative stress biomarkers, and pro-inflammatory cytokine levels. Our findings aim to support the development of ARB as a complementary treatment to alleviate the hepatic side effects of MTX and enhance clinical outcomes.

3. Methods

3.1. Chemicals

All required chemical agents, including ARB, trichloroacetic acid (TCA), MTX, Thiobarbituric acid (TBA), GSH, Bradford reagent, and the reagents for biochemical assays (e.g., 5,5-dithiobis [2-nitrobenzoic acid) (DTNB) and bovine serum albumin (BSA)], were provided by Sigma-Aldrich, USA. All chemical agents were of analytical grade and used without further purification.

3.2. Animals and Experimental Design

The Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at Ahvaz Jundishapur University of Medical Sciences approved the research (IR.AJUMS.ABHC.REC.1402.018). Forty male Wistar rats (180 to 220 g) were provided by the Central Animal House Facility at Ahvaz Jundishapur University of Medical Sciences, Iran. These animals were maintained in a regulated environment at 25 ± 1°C with a 12-hour dark/light cycle. Before experimental interventions, a 7-day acclimatization period was observed. The care of these animals adhered strictly to the instructions of the National Institutes of Health (NIH Publication No. 85-23, revised 1985).

The animals were randomly assigned to five groups, each comprising eight rats, as follows: Group I (control): Rats received normal saline (N/S) orally once daily for 10 days. On day 9, they also received a single intraperitoneal (i.p.) injection of N/S. Group II (MTX): Rats were administered N/S orally once daily for 10 consecutive days. On day 9, a single dose of MTX (MTX; 20 mg/kg, i.p.) was given. Group III (MTX + ARB 25): Rats received ARB suspended in N/S at 25 mg/kg orally once daily for 10 days (For all treatment groups, ARB was dissolved in N/S and administered via oral gavage at a standardized volume of 5 mL/kg of body weight), with a single MTX dose (20 mg/kg, i.p.) administered on day 9. Group IV (MTX + ARB 50): Rats were given ARB at 50 mg/kg orally once daily for 10 days. On day 9, they also received MTX (20 mg/kg, i.p.). Group V (MTX + ARB 100): Rats received ARB suspended in N/S at 100 mg/kg orally once daily for 10 days, along with a single MTX injection (20 mg/kg, i.p.) on day 9. Treatment occurred from day 0 to day 9 (10 days total), with MTX administered on day 9 in the morning, 1 hour after the final ARB dose.

In addition, to justify the sample size of n = 8 per group, we conducted a power analysis to ensure the study had adequate statistical power to detect meaningful differences while adhering to the ethical principles of the 3Rs (replacement, reduction, and refinement). The sample size was determined based on previous studies that used similar experimental protocols in hepatotoxicity models and employed comparable numbers of animals (19, 20, 29).

3.3. Sample Collection and Preparation

After a 24-hour interval following the final treatment, rats were anesthetized with ketamine and xylazine (80/8 mg/kg, intraperitoneally). Whole blood (2 cc) was collected from the jugular vein and centrifuged at 3,000 RPM for 15 minutes to isolate serum, which was stored at -20°C for biomarker analysis (ALP, AST, ALT). Liver tissue specimens were collected immediately after blood sampling. One section was fixed in 10% phosphate-buffered formalin for histological analysis, while another portion was homogenized in chilled Tris–HCl buffer (0.1 M, pH 7.4). The homogenate was centrifuged, and the supernatant was stored at -80°C for future analyses. Tissue protein levels were measured using the Bradford method, with BSA as the standard reference. The supernatant was also used for biochemical assays (30, 31).

3.4. Serum Biochemical Assays

Serum biochemical parameters, including AST, ALT, and ALP, were measured to assess hepatic function. Serum samples were collected from each rat according to the specified experimental protocols and stored at -80°C until assessment. ALT, ALP, and AST activities were determined using commercial colorimetric assay kits (Wiesbaden, Germany) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Samples were incubated with specific substrates, resulting in the formation of colored products proportional to the enzymatic activity. The absorbance was evaluated spectrophotometrically at appropriate wavelengths with a calibrated spectrophotometer (Model 1200, UNICO Instruments Co., USA). Enzyme activity was reported in IU/L, based on standard curves generated from known enzyme concentrations.

3.5. Tissue Biochemical Assays

To examine the ARB protective effect against MTX-related hepatotoxicity in rats, liver tissues were analyzed for various biochemical markers, including oxidative stress indicators, antioxidant enzyme activities, and inflammatory cytokines.

3.6. Malondialdehyde

The level of malondialdehyde (MDA) was quantified employing Aust’s method, as described previously (TBARS assay) (32, 33). Briefly, tissue supernatant (0.5 mL) was transferred into tubes containing TCA (1.5 mL; 10%, w/v). Subsequently, the tubes were centrifuged (3,400 rpm for 10 min) to precipitate proteins. Following centrifugation, the supernatant (1.5 mL) was mixed with TBA (2 mL; TBA; 0.67%, w/v) in separate tubes. The resulting solution received incubation in boiling water for 30 min to facilitate the formation of a pink chromogen complex indicative of MDA-TBA adducts. After incubation, the tubes were immediately cooled down. The absorbance of the resultant pink solution was evaluated at 532 nm by a Shimadzu UV-1650 PC spectrophotometer (Japan). The MDA concentration (in nmol/mg protein) was assessed with a certain absorbance coefficient associated with TBA-MDA complexes.

3.7. Reduced Glutathione

Reduced GSH concentrations were evaluated with Ellman’s reagent. Liver homogenates were precipitated with 25% TCA. The clear supernatant was reacted with 0.5 mM DTNB, and absorbance was measured at 412 nm using a Shimadzu UV–Vis spectrophotometer (Japan). The GSH level was calculated from a standard curve and reported in nmol/mg of protein (34).

3.8. Protein Carbonyl

Protein carbonyls were quantified by reacting 500 µL of DNPH (0.1%) in 2N HCl with liver supernatant (500 µL) in the dark for an hour. The mixture was treated with 20% TCA, then centrifuged. The pellet was washed with ethanol–ethyl acetate (0.5 mL) and resuspended in 1000 µL of Tris-buffered 8M guanidine HCl. A Shimadzu UV-1650 PC UV-Vis spectrophotometer (Japan) was used to measure absorbance at 370 nm, and the data were reported as nmol carbonyl/mg protein (35).

3.9. Antioxidant Enzymes

The concentrations of nitric oxide (NO) (in nmol/mg protein) and GSH peroxidase (GPx), SOD, and CAT (expressed as units/mg of protein) activities in hepatic tissues were determined utilizing commercially available kits (ZellBio, Germany), adhering strictly to the manufacturer’s protocols.

3.10. Pro-inflammatory Cytokines

Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) kits for rats (IBL, USA) were used to assess TNF-α and IL-1β tissue concentrations as instructed (pg/mg protein).

3.11. Histopathological Examination

Liver tissues from experimental rats were examined to assess MTX-induced hepatotoxicity and ARB's protective role. After euthanasia, liver samples were fixed in 10% buffered formalin for at least 24 hours, dehydrated in graded alcohol, embedded in paraffin, and sliced into 5 µm sections using a Leica microtome. Sections were stained with Hematoxylin and Eosin (H&E) — hematoxylin for 8 minutes, 1% acid alcohol for 15 seconds, and eosin for 2 minutes. Slides were evaluated under a 400x light microscope (Nikon) for fat deposition, RBC congestion, pyknosis, and inflammation by a blinded observer. Severity was scored from 0 (no injury) to 3 (severe injury), and overall scores were averaged across groups.

3.12. Statistical Analysis

All statistical procedures were conducted using appropriate analytical methods to ensure rigor and reproducibility. Comparisons of biochemical parameters across the control, MTX-only, and MTX plus ARB treatment groups were performed using a one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA), followed by Tukey’s post hoc test for pairwise evaluations. These results are reported as mean ± standard deviation (SD). Given the nature of histological assessments in mouse liver tissue, nonparametric statistical methods were used. Group differences were evaluated using the Kruskal–Wallis test, with Dunn’s post hoc test used to determine significant multiple comparisons. Statistical significance was defined as a P-value < 0.05.

4. Results

4.1. Effects of Arbutin on Liver Function: Influence on Serum ALP, AST, and ALT Levels

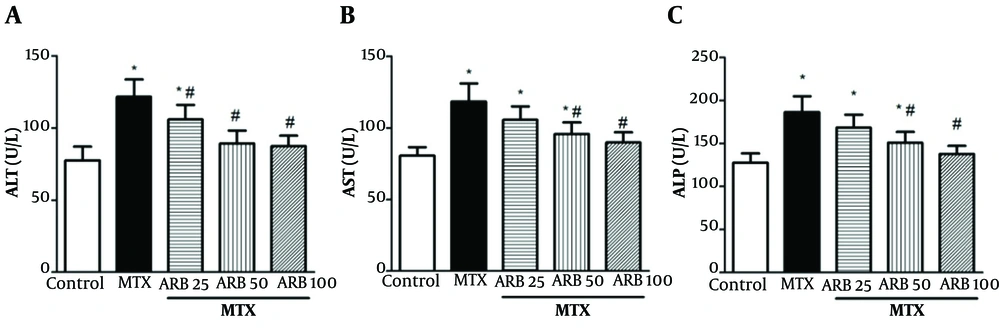

Serum AST, ALP, and ALT concentrations serve as indicators of liver function and integrity. Their concentrations were markedly elevated in the MTX-intoxicated group compared with controls, indicating substantial hepatotoxicity (all P < 0.05; Figure 1). However, ARB pretreatment at 25, 50, and 100 mg/kg markedly reduced serum ALT concentrations in animals with hepatotoxicity (P < 0.05). Notably, ALP and AST levels exhibited a significant reduction with concentrations of 50 and 100 mg/kg of ARB, indicating a dose-dependent hepatoprotective effect (P < 0.05).

Effect of arbutin (ARB) on of A, ALT; B, AST; and C, ALP concentrations in hepatotoxicity caused by methotrexate (MTX). Data are presented as mean ± SD (n = 8), analyzed via one-way ANOVA, with subsequent application of Tukey’s multiple comparisons post hoc test. * P < 0.05 vs. the control group; # P < 0.05 vs. the MTX group.

4.2. Effects of Arbutin on Oxidative Stress Parameters: Impact on Malondialdehyde, Nitric Oxide, and Protein Carbonyl Protein Carbonyl Levels in Liver Tissue

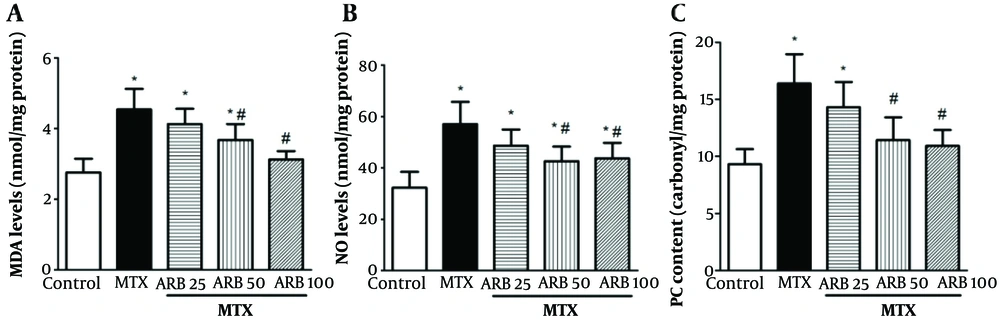

Protein carbonyl, NO, and MDA levels in liver tissue were markedly elevated in MTX-intoxicated animals versus the controls (P < 0.05 Figure 2). However, pretreatment with ARB at 50 and 100 mg/kg for 10 continuous days notably decreased such parameters versus MTX group, with significant reductions in all levels of OS parameters (MDA, NO, and PC) (P < 0.05). Additionally, ARB administration at 25 mg/kg did not significantly alter these OS parameters (PC, NO, and MDA) compared with controls.

Impact of arbutin (ARB) on A, malondialdehyde (MDA); and B, NO concentrations; and C, PC content in methotrexate (MTX)-related hepatotoxicity, in MTX-induced hepatotoxicity. Data are presented as mean ± SD (n = 8), analyzed via one-way ANOVA, with subsequent application of Tukey’s multiple comparisons post hoc test. * P < 0.05 vs. the control group; # P < 0.05 vs. the MTX group.

4.3. Arbutin Impact on Superoxide Dismutase, Catalase, and GPx Enzyme Activities and Cellular Glutathione Content in Liver Tissue

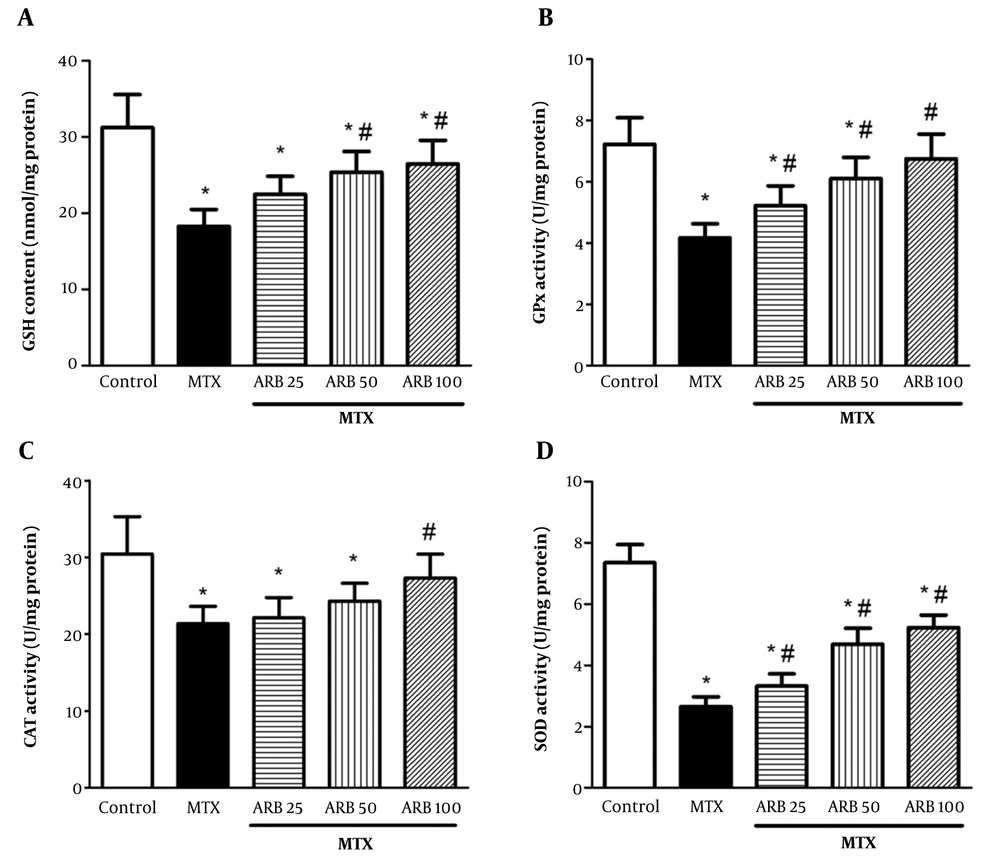

Cellular glutathione content was significantly diminished in rats intoxicated with MTX compared to controls (P < 0.05). Arbutin at 50 and 100 mg/kg notably augmented GSH content (P < 0.05). Superoxide dismutase, CAT, and GPx activities were notably lower in MTX-intoxicated rats compared to controls (P < 0.05). Pretreatment with ARB at 25, 50, and 100 mg/kg for 10 continuous days notably enhanced GPx and SOD activities in the ARB group versus the MTX group (P < 0.05 for both GPx and SOD) (Figure 3B and D). Moreover, ARB at 100 mg/kg markedly elevated CAT activity (P < 0.05) (Figure 3).

Effect of arbutin (ARB) on A, GSH content in methotrexate (MTX)-related hepatotoxicity; B, GPx; C, CAT; and D, superoxide dismutase (SOD) activity. Data are presented as mean ± SD (n = 8), analyzed via one-way ANOVA, with subsequent application of Tukey’s multiple comparisons post hoc test. * P < 0.05 vs. the control group; # P < 0.05 vs. the MTX group.

4.4. Effects of Arbutin on Inflammatory Cytokines: Impact on TNF-α and IL-1β in Liver Tissue

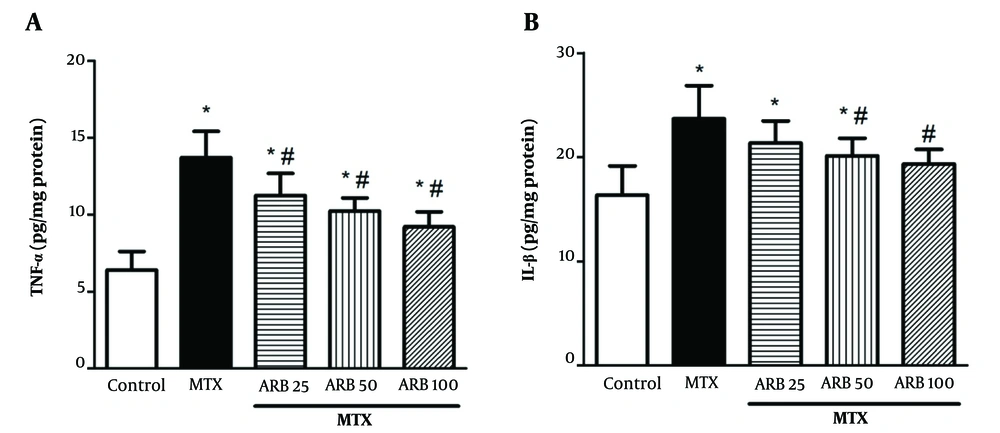

Methotrexate significantly increased hepatic IL-1β and TNF-α concentrations compared with controls, indicative of a heightened inflammatory response (P < 0.05 for both IL-1β and TNF-α), as depicted in Figure 4A and B, respectively. ARB treatment at 25, 50, and 100 mg/kg notably decreased MTX-related elevation in TNF-α levels (P < 0.05). Additionally, pretreatment with ARB at 50 and 100 mg/kg for 10 consecutive days notably reduced MTX-induced elevation in IL-1β levels compared with the MTX group (P < 0.05 for both 50 and 100 mg/kg).

Effect of arbutin (ARB) on A, TNF-α in methotrexate (MTX)-related hepatotoxicity; and B, IL-1β. Data are presented as mean ± SD (n = 8), analyzed via one-way ANOVA, with subsequent application of Tukey’s multiple comparisons post hoc test. * P < 0.05 vs. the control group; # P < 0.05 vs. the MTX group.

4.5. Effects of Arbutin on the Histopathological Features of Liver Tissue

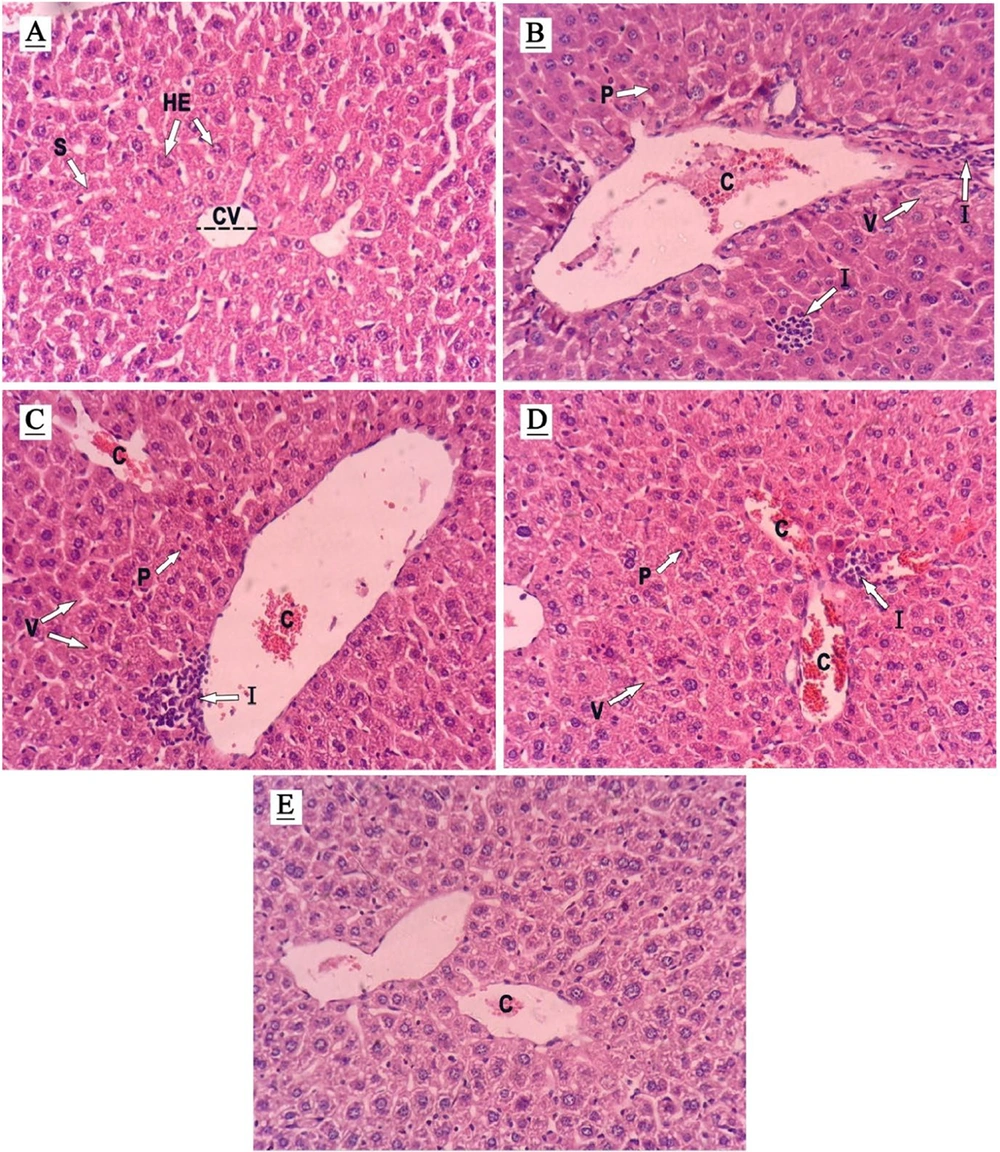

The liver tissue of the controls displayed a standard cellular architecture with intact cytoplasm, well-defined nuclei, clear sinusoids, and unobstructed central veins and portal tracts (Figure 5 and Table 1). In stark contrast, liver samples from MTX-treated rats exhibited severe pathological changes, like widespread cellular damage, congestion of red blood cells (RBCs), significant lipid accumulation, infiltration by inflammatory cells, and nuclear pyknosis, highlighting the extent of MTX-induced hepatotoxicity (see Figure 5B and Table 1). Notably, ARB administration at 50 and 100 mg/kg resulted in substantial improvement in these adverse changes, with a dose-dependent restoration of liver tissue integrity. The 25 mg/kg dose, however, showed limited improvement, indicating a dose-response relationship in the hepatoprotective effect of ARB (Figure 5C to E).

Histopathological assessment (hematoxylin and eosin- stained liver sections, Magnification ×400) demonstrating the effects of arbutin (ARB) on methotrexate (MTX)-related hepatotoxicity in liver tissue. A, controls; B, MTX group; C, MTX + ARB 25; D, MTX + ARB 50; E, MTX + ARB 100. Key: C, congestion of RBCs; CV, central vein; I, inflammatory cell infiltration; HE, hepatocyte; P, pyknosis; S, sinusoids; V, vacuolation of hepatocytes.

| Histological Criteria | Groups | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control | MTX | MTX+ARB25 | MTX+ARB50 | MTX+ARB100 | |

| Infiltration of inflammatory cells | 0.18 ± 0.50 | 0.64 c ± 2.13 | 0.71 c ± 1.75 | 0.52 c, d ± 1.38 | 0.64 d ± 1.13 |

| Congestion of RBCs | 0.52 ± 0.63 | 0.83 c ± 2.13 | 0.76 c ± 2 | 0.64 c, d ± 1.88 | 0.83 c, d ± 1.22 |

| Pyknosis | 0.64 ± 0.88 | 0.52 c ± 2.38 | 0.83 c ± 1.88 | 0.89 c, d ± 1.75 | 0.71 d ± 0.75 |

Abbreviations: MTX, methotrexate; ARB, arbutin.

a Data are mean ± SD (n = 8).

b Statistical analysis was performed using the Kruskal–Wallis test followed by Dunn’s post hoc test.

c P < 0.05 Vs. the control group.

d P < 0.05 Vs. MTX group

5. Discussion

The World Health Organization recognizes MTX as a crucial medicine, but it is also known for its hepatotoxic effects even at low doses (36). Methotrexate is a commonly used drug for cancer therapy and immunosuppressant, but it has severe side effects on organs like the liver, kidneys, and bone marrow (37, 38). Therefore, the use of substances like ARB that can prevent or reverse liver injury caused by MTX can provide significant clinical benefits.

In light of the increasing global preference for natural treatments over synthetic alternatives, attributed to their reduced side effects, our study rigorously examined the hepatoprotective effects of ARB, a natural phenolic compound derived from various plants, on liver damage induced by MTX in rat models (39). Our findings indicate, for the first time, that a 10-day pretreatment with ARB significantly protects the liver from MTX-induced hepatotoxicity in rats.

This finding aligns with prior studies showing that natural antioxidants protect liver function markers in various models of MTX-induced hepatotoxicity (40, 41). Beyond the observed reductions in serum transaminases, these findings suggest that ARB may stabilize hepatocellular membranes by limiting ROS-driven lipid peroxidation and preserving mitochondrial function — two central events in early MTX-induced hepatocellular injury. Reduction in enzyme leakage likely reflects ARB’s capacity to modulate intracellular redox signaling, thereby preventing mitochondrial permeability transition and subsequent necrotic or apoptotic cell loss (39).

OS is an essential factor in MTX-induced hepatotoxicity, mainly due to the imbalance between the antioxidant defense mechanisms and the generation of reactive nitrogen and oxygen species (RONS) (42). Conversely, ARB has antioxidant impacts, either by directly scavenging free radicals by elevating antioxidant enzyme activity (43). Therefore, ARB may provide hepatoprotective benefits through its antioxidant properties. Important GPx, CAT, and SOD antioxidant enzymes serve as the first line of defense against oxidative damage by neutralizing harmful radicals (29). In our study, pretreatment of rats with ARB (25, 50, and 100 mg/kg for SOD and GPx; 100 mg/kg for CAT) significantly increased the activities of these enzymes, thereby enhancing the liver's antioxidative capacity. These enzymes help mitigate OS by decomposing superoxide radicals and hydrogen peroxide, which are harmful by-products of cellular metabolism. The increase in SOD and CAT activities under ARB treatment could prevent the conversion of these reactive species into more toxic compounds, such as peroxynitrite, which exacerbates cellular damage (39). The coordinated increase in GPx, SOD, and CAT following ARB administration reflects not merely enzyme upregulation but a broader restoration of the antioxidant network that counters MTX-induced NADPH depletion. This suggests that ARB may support the regeneration of reduced GSH and enhance the liver’s resilience to ROS-mediated macromolecular damage. The concurrent reduction in MDA and PCs further supports the hypothesis that ARB interrupts the feed-forward oxidative cycle that perpetuates hepatocellular dysfunction in MTX toxicity (44). Methotrexate-induced hepatotoxicity is linked to decreased liver antioxidant enzymes, including GPx, CAT, SOD, and GSH (44, 45). This deficiency leads to protein oxidation, DNA damage, and lipid peroxidation (LPO), resulting in organ dysfunction and cell death. In our study, pretreatment with ARB at 50 and 100 mg/kg notably decreased MDA levels, as a critical marker of LPO (46). These observations are supported by previous literature indicating that ARB can neutralize free radicals and inhibit oxidative mechanisms induced by carbon tetrachloride, leading to cellular damage (39). Moreover, NO, while essential for various physiological functions, can exacerbate liver injury when produced in excess by reacting with superoxide radicals to form highly reactive peroxynitrite, thereby leading to further oxidative stress and cellular damage (47, 48). Our investigation found that ARB (50 and 100 mg/kg) effectively decreased NO levels. This reduction in NO levels has the potential to prevent peroxynitrite formation, thereby safeguarding against cellular apoptosis and oxidative damage. This mechanism is corroborated by other research studies (49, 50). The PC are markers of protein oxidation, and their reduction by ARB (50 and 100 mg/kg) in our study indicates its protective role against oxidative protein damage. Consistent with earlier research, we found that MTX elevates hepatic PC concentrations, suggesting that it induces oxidative damage to hepatic proteins and lipids.

Furthermore, Inflammation is another critical component of MTX-induced hepatotoxicity. IL-1β and TNF-α, pro-inflammatory cytokines, are the primary mediators of inflammation, which can exacerbate liver injury (51). Arbutin treatment (25, 50, and 100 mg/kg for TNF-α; 50 and 100 mg/kg for IL-1β) markedly reduced these cytokines, suggesting that its protective effects may also involve modulation of the inflammatory response. This anti-inflammatory action might be mediated by suppressing NF-κB, a key regulator of inflammatory processes. Certain natural compounds can suppress NF-κB activation, thus lowering the pro-inflammatory cytokine expression and ameliorating inflammation-induced organ damage (52, 53). The attenuation of TNF-α and IL-1β also indicates a possible upstream regulatory effect of ARB on immune-mediated hepatic injury. By reducing cytokine-driven recruitment of neutrophils and macrophages, ARB may limit secondary inflammatory amplification and prevent progression toward chronic hepatic remodeling. This aligns with the concept that ARB not only mitigates biochemical disturbances but may also modulate cross-talk between oxidative and inflammatory pathways, which collectively shape the trajectory of MTX-induced liver damage (54). The hepatic histopathological findings in this study align with the biochemical evaluations and reveal structural alterations in the liver tissue of MTX-treated rats. MTX at 20 mg/kg causes histopathological damage in the liver, including fat accumulation, infiltration of inflammatory cells, RBC congestion, and pyknosis. These results support those from prior reports (22, 37). Furthermore, the histopathological improvements observed in liver tissue following ARB treatment confirm the biochemical findings.

5.1. Strengths and Limitations

A notable strength and innovative aspect of this study is that it represents the first evaluation of the hepatoprotective effects of arbutin in a model of liver injury induced by MTX. This research broadens our understanding of natural phenolic compounds as potential adjunct therapies for MTX-related hepatotoxicity. By demonstrating that arbutin has dose-dependent protective effects against biochemical, oxidative, inflammatory, and histopathological changes, this study provides new evidence supporting arbutin's translational potential. It positions arbutin as a promising candidate for future preclinical and clinical research.

Despite its strengths, this investigation has several limitations that should be acknowledged to understand the findings better. First, although the experimental design included five well-defined groups to assess the dose-dependent hepatoprotective effects of arbutin against MTX toxicity, the lack of an “arbutin-only” group remains a methodological limitation. Without this control group, it cannot be definitively confirmed within the same experimental framework that ARB alone causes no physiological changes or subclinical hepatotoxicity. While previous studies have independently shown the biochemical safety and non-toxic profile of ARB in healthy rodents, as well as its antioxidant and anti-inflammatory effects when administered alone, including such a group would have strengthened the internal validity and removed any lingering doubts. Second, the study evaluated only short-term pretreatment, so the long-term effects, pharmacodynamics, and potential accumulation of ARB were not examined. Lastly, although biochemical and histopathological markers were thoroughly assessed, mechanistic pathways were inferred based on prior evidence rather than directly measured. Future research incorporating ARB-only controls, longer treatment durations, and molecular pathway analyses will be essential to fully understand the mechanisms and translational relevance of hepatoprotective effects.

5.2. Conclusions

Arbutin has demonstrated a strong protective effect against MTX-induced hepatotoxicity in rats by modulating oxidative stress, boosting antioxidant defenses, and reducing inflammation. This study confirms ARB's ability to significantly decrease liver enzymes and oxidative stress markers while improving tissue health.