1. Background

Topical drug delivery is the most popular noninvasive method for the treatment of ocular diseases; however, although the drug can reach the treatment area from conventional dosage forms, achieving adequate doses of the drug and maintaining them in the ophthalmic area are obstacles (1). Eye drops are traditionally the first option for therapy of inflammatory infections and account for up to about 90% of the worldwide eye product market, although their bioavailability is around 5% (2). In addition, physiological and anatomic factors of the eye, protein binding, and enzymatic degradation can decrease pharmacokinetic parameters (3, 4). Nanotechnology could increase drug accumulation at the site of action, decrease side effects (3, 5), control drug delivery, and improve the stability of therapeutic agents (6). There are several types of nanoscale delivery systems, such as nanoemulsions, nanoparticles, and nanosuspensions. Nanogels are three-dimensional hydrogel particles that carry nanoparticles. This delivery system means that nanosized particles are incorporated into the hydrogel delivery system. The benefits of nanogels include swelling, adjustable size, biocompatibility, and hydrophilicity. Hence, this delivery system highlights the merits of both the nanoparticle delivery system and hydrogel. Alginate is an anionic hydrocolloid polymer extracted from seaweed, composed of 1,4-linked-α-L-guluronic acid and β-D-mannuronic acid residues (7). Alginate is a biocompatible and biodegradable polymer, so numerous studies have been conducted on its potential application as nanoparticles or nanogels in drug delivery systems (8, 9). Alginate can chelate in the presence of divalent calcium, which is useful for preparing a nanogel (10). Alginate nanogel (Alg-NG) is prepared by two usual methods, emulsification/external and emulsification/internal gelation. In the latter method, a higher concentration of calcium reacts with alginate in the medium, causing the nanogel to shrink, resulting in a smaller size compared to the first method (11).

Chitosan, a cationic polysaccharide obtained by alkaline N-deacetylation of chitin, has been widely employed in pharmaceutical and biomedical fields owing to its unique properties such as biodegradability, biocompatibility, and non-toxicity (12). Hence, because of chitosan's structure and unique properties, it can be used for coating various types of materials. Ionic interactions between the amine group of chitosan and the carboxylic alginate group lead to the formation of a polyelectrolyte complex (13). Consequently, in addition to the chelation reaction between alginate and divalent cations, such as calcium, to make a nanogel, polyelectrolyte complexes can also be easily formed between alginate and chitosan. This combination could help adherence to mucus membranes such as ophthalmic tissue, etc.

Bacterial keratitis is a visually threatening ocular infectious pathology. In some cases, it may have an explosive onset and may end up with rapidly progressive stromal inflammation. Untreated bacterial keratitis often leads to progressive tissue destruction with corneal perforation (14, 15). Fluoroquinolones are promising antibacterial chemotherapeutic agents for the treatment of different infections. Ofloxacin is a widely used fluoroquinolone and is active against Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria.

While few studies have considered the properties of an alginate/chitosan nanogel (10, 13, 16), the nanogels were not prepared by internal gelation. Moreover, the polyelectrolyte complex formed by alginate and chitosan could impact the release of the drug from the nanogel. Hence,

2. Objectives

This study aims to develop and characterize an ofloxacin-loaded alginate-chitosan nanogel (Alg-Chi NG) with an internal gelation method for potential topical ocular treatment, which could adhere to cells and enhance the retention time of the nanogel on the eye.

3. Methods

Sodium alginate (W2015.2, M/G =1.5, inherent viscosity of 1% solution ranging from 5 to 40, approximately 12.8 mPa.s, Lot number: MKBT7870V, molecular weight: 12 - 14 kDa) and chitosan (low molecular weight, 448869, molecular weight: 50 - 190 kDa) were bought from Sigma-Aldrich (St Louis, Missouri, United States). Calcium carbonate, Span80, and tripolyphosphate were bought from Merck (Darmstadt, Germany). The liquid paraffin and acetic acid glacial were obtained from Dr. Moiallali, Industrial Chemical Company (Tehran, Iran). Ofloxacin was obtained from Temad, an active pharmaceutical ingredient company (Karaj, Iran).

3.1. Preparation of Nanogels

3.1.1. Alginate Nanogel Preparation Containing Ofloxacin

Alginate nanogels were prepared by emulsification/internal gelation (17). First, in a vessel, 4% W/V of alginate solution (5 mL) was prepared, then 8 mg of ofloxacin was dissolved in it. Then 32 mg of calcium carbonate was dispersed in this solution, so a suspension was prepared. In addition, a mixture of paraffin and surfactant was prepared by incorporating Span80 (1% W/V) with paraffin separately. Then, the emulsion was prepared by adding 8.5 mL of the paraffin-surfactant combination into the alginate suspension under an overhead stirrer (IKA, Germany), at 400 rpm. This speed was chosen to make uniform flow in the vessel, in addition to producing a narrower size distribution (17). In another beaker, acidic paraffin was prepared by dissolving 0.7 mL glacial acetic acid in 50 mL paraffin. After 15 min emulsification of the sample, the pH of the emulsion was adjusted to 4.7-5 by slowly adding acidic paraffin to the W/O emulsion. An acidic medium is necessary for the dissociation and dissolution of calcium. After 40 min, the Alg-NG was prepared. In the following steps, nanogels were centrifuged, washed to remove excess oil, and purified.

3.1.2. Alginate–Chitosan Nanogel Containing Ofloxacin

To prepare Alg-Chi NGs, Alg-NGs were initially prepared without any pretreatment involving chitosan. Next, a chitosan solution was prepared separately. Based on preliminary studies, the proportion of chitosan to alginate was chosen as 3:1 for further experiments. After preparation of the Alg-NG, in a separate beaker, chitosan (1 mg/mL) was dissolved in 0.1 M acetic acid and the pH was adjusted to 4.8. For the preparation of paraffinized chitosan, aqueous chitosan was emulsified in the oily medium. Span80 was used as an emulsifier. Hence, 24.5 mL of prepared chitosan was emulsified in the equivalent volume of paraffin containing 0.4% W/V Span80, and stirred for 10 min to make a paraffinized chitosan. The previously prepared Alg-NG was added dropwise to the prepared paraffinized chitosan under an overhead stirrer at 400 rpm for 30 min. The Alg-NGs coated with chitosan were prepared, centrifuged, washed, and purified.

3.2. Characterization of Alg-NGs and Alg-Chi NGs

3.2.1. Particle Size and Zeta Potentials of Nanogels

The particle size of alg-nanogels and alg-chi nanogels was determined by Microtrac Dynamic Light Scattering (Nanotrac Flex, Haan/Duesseldorf, Germany). This device features a small immersion probe. The sample was dispersed in 5 mL of deionized water at 25℃, allowing the probe to access the sample. The light emitted by a laser beam was guided to the optical probe by a fiber; this is focused into the sample through the protective sapphire window. The laser light reflected by the protective window and the 180° backscattered light were collected and guided through a fiber to a detector by a “Y” optical splitter. The measuring range of the instrument is between 0.8 nm to 6.5 µm. The zeta potential of nanogels was determined by Stabino Zeta in combination with Nanotrac Flex (Haan/Duesseldorf, Germany).

3.2.2. Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy

Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy spectra of alg-NG and alg-chi NGs were confirmed by the Perkin-Elmer instrument. The spectrum was carried out in transmittance mode in the range of 450 cm(-1) to 4000 cm(-1).

3.2.3. Field Emission Scanning Electron Microscopy

The morphology of alg-nanogel and alg-chi nanogel was examined by field emission scanning electron microscopy (Tescan Co. Brno, Czech Republic). For the preparation of nanogels, first, a dilute solution of nanogels was prepared and placed on an aluminum sheet, dried in a vacuum oven, and then exposed to electronic waves.

3.2.4. Encapsulation Efficiency and Loading Capacity of Nanogels

The encapsulation efficiency (EE) of ofloxacin in two types of nanogels was determined indirectly. The prepared Alg-NGs were centrifuged at 10000 g for 30 min to separate the supernatant. The amount of ofloxacin in the supernatant was then measured by using Ultraviolet-visible Spectroscopy (PerkinElmer, Shelton, USA) at a wavelength of 287 nm. This procedure was conducted separately for Alg-Chi NG. The percentage of EE of the two types of nanogels was determined using Equation 1.

For the determination of LC, both types of nanogels were freeze-dried and weighed individually. The percentage of LC of the two types of nanogels was determined using Equation 2. All the experiments were done in triplicate.

3.2.5. Swelling

The swelling of nanogels was determined by the gravimetric method (18). A determined amount of freshly prepared alg-nanogels and alg-chi nanogel was weighed and then soaked in a phosphate buffer at a pH of 7.4. The weight of the sample was measured after 5 min using the following Equation 3:

Where Ws is the initial dry weight of nanogel before being placed into a phosphate buffer of pH 7.4, and Wn is the wet weight of nanogel after being placed into the phosphate buffer.

3.2.6. in vitro Drug Release and Kinetic of Drug Release

The in vitro drug release study of ofloxacin from alg-nanogel and alg-chi nanogel was conducted using a dialysis membrane with a molecular weight cut off of 12 kDa, separately. A precise amount of freeze-dried nanogels was dispersed in 25 mL phosphate buffer, pH 7.4, and placed in the dialysis membrane. These studies were performed at 37°C and stirred at 100 rpm. At predefined time intervals (0.25, 0.5, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 24, and 48 h), 2 mL of medium was removed and replaced with fresh buffer. The amount of ofloxacin in alg-nanogel and alg-chi nanogel was measured separately by Ultraviolet-visible spectroscopy at 287 nm.

3.2.7. Evaluation of the Kinetic Model

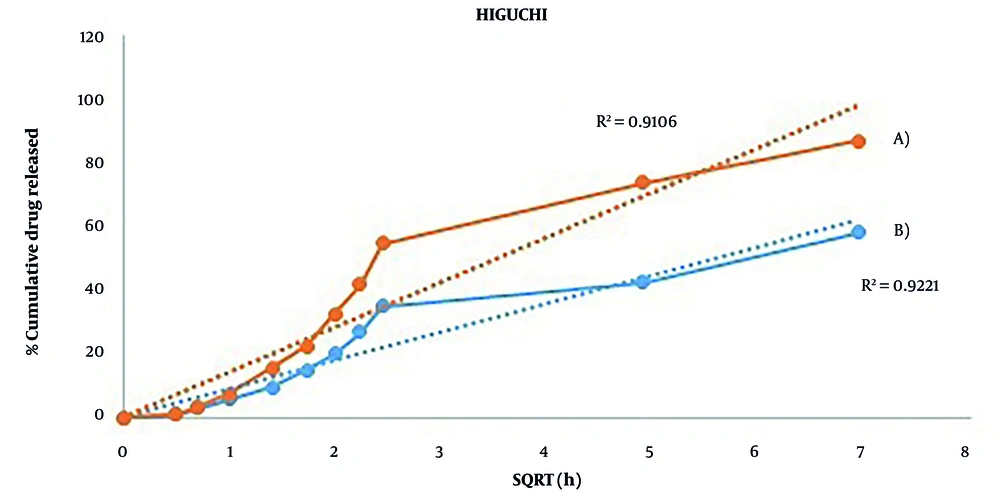

The release kinetics of the drug molecule from the polymeric nanogels were studied. Various kinetic models were employed to analyze the drug release kinetics from two types of nanogels, including zero order, first order, Higuchi, and Hixson-Crowell models, to assess the release mechanism. The selection of the most suitable kinetic model was based on the adjusted R² value being close to 1.

3.2.8. Statistical Rigor

All the experiments were performed in triplicate and the results were expressed as mean value ± standard deviation (SD) for in vitro experiments.

4. Results

The interaction between alginate and calcium occurred in the Alg-NG through emulsification/internal gelation. After preparing the emulsion, acidic paraffin containing glacial acetic acid was added to the emulsion. The acidic medium is suitable for dissolving the calcium, which is necessary for the interaction between calcium and alginate. Additionally, glacial acetic acid has a low water content, so the ratio of water to oil in the emulsion remained unchanged. To incorporate Alg-NG with chitosan, the chitosan was first dispersed in paraffin containing Span80. This step was taken to decrease the reaction rate between the Alg-NG and chitosan, resulting in smaller particle sizes.

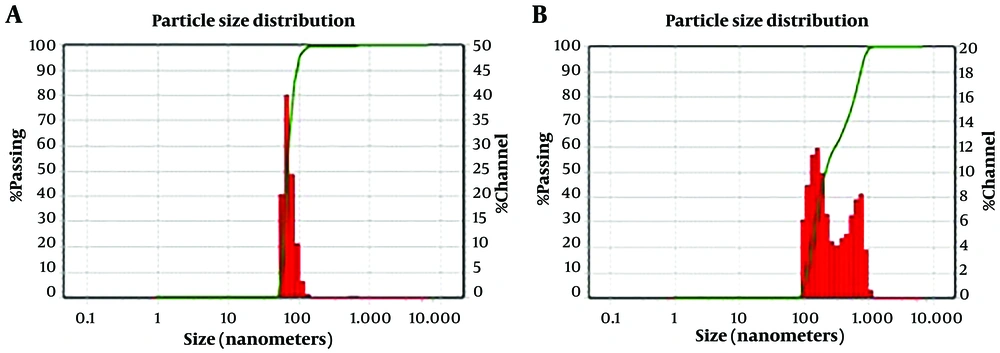

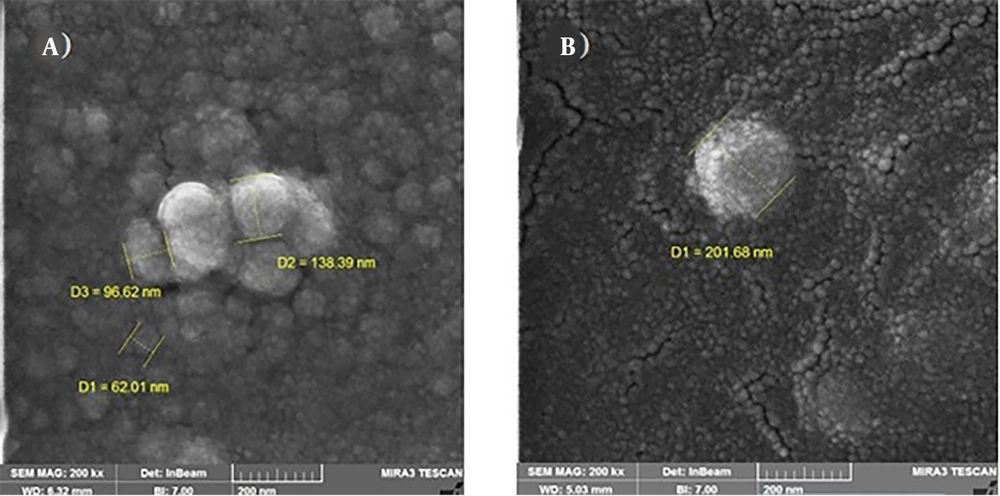

The ofloxacin-loaded alg-NG had a 70 nm hydrodynamic diameter and ofloxacin-loaded alg-chi NG had a 150 nm hydrodynamic diameter with a relatively broad distribution, with 60% of the nanogels being smaller than 300 nm (Figure 1). The zeta potential of ofloxacin-loaded alg-nanogel and ofloxacin-loaded alg-chi-nanogel had a high negative surface charge of -150 ± 6.2 mV and -16 ± 0.9 mV, respectively. We showed that the appearance of alg-nanogel with field emission scanning electron microscopy was smooth spherical particles within the range of 70 nm. Also, the image of alg-chi nanogel was spherical (Figure 2).

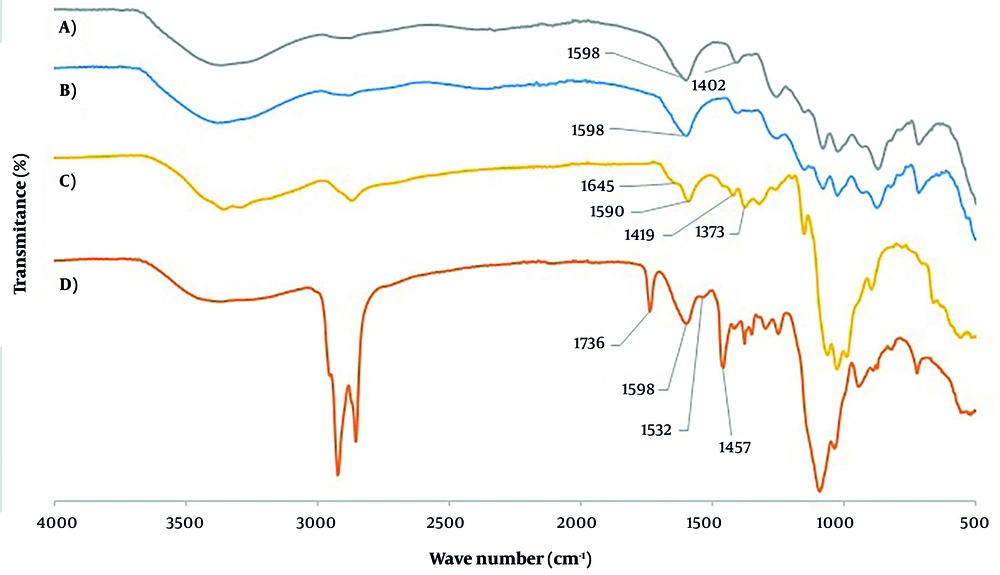

The Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FT-IR) spectra of sodium alginate, sodium Alg-NG, chitosan, and alginate/chitosan composites are presented in Figure 3. The FT-IR spectrum of sodium alginate shows a characteristic band near 1024 cm⁻¹, which is attributed to C–O–C stretching vibrations of its saccharide framework. Moreover, the bands at 1598 cm⁻¹ and 1402 cm⁻¹ are assigned to the asymmetric and symmetric stretching vibrations of carboxylate (–COO⁻) salt groups, respectively.

The chitosan spectrum displays a broad and intense band at 3360 cm⁻¹, which can be attributed to the combined effects of O–H stretching, N–H stretching, and intermolecular hydrogen bonding within the polysaccharide structure. A strong absorption band observed at 2870 cm⁻¹ corresponds to C–H stretching vibrations of the chitosan backbone. Additionally, two characteristic peaks at 1645 cm⁻¹ and 1590 cm⁻¹ are assigned to C=O stretching of the amide I (NHCO) group and N–H bending vibrations of the NH₂ group, respectively. Bands appearing at 1419 cm⁻¹ and 1373 cm⁻¹ are attributed to N–H stretching of the amide and ether linkages and to the amide III band, respectively. Other distinctive peaks of chitosan include those at 1151 cm⁻¹, corresponding to the (1–4) glycosidic bond, 1024 cm⁻¹ related to C–O–C stretching within the glucose ring, and 1064 cm⁻¹ associated with CH–OH vibrations in cyclic structures.

In the chitosan/alginate spectrum, a broad absorption band appears at 3375 cm⁻¹, indicating interactions arising from the combination of chitosan and alginate. These spectral modifications suggest that the negatively charged carboxylate groups of alginate interact electrostatically with the positively charged ammonium groups of chitosan, leading to the formation of a polyelectrolyte complex. Further evidence of ionotropic gelation is provided by the shift of the chitosan amide I peak from 1645 cm⁻¹ to 1598 cm⁻¹. Additionally, the asymmetric and symmetric stretching bands of alginate –COO⁻ groups shift to 1532 cm⁻¹ and 1457 cm⁻¹, respectively, confirming complex formation. Considering the peaks of Alg-Chi NG were shown besides Alg-NG and chitosan peaks, a new peak was observed at 1736 cm⁻¹, which was not present in the alginate and chitosan, separately. This confirms the polyelectrolyte complex between alginate and chitosan.

The encapsulation efficiency of ofloxacin-loaded alg-nanogel was 39.2 ± 3.62%, and the encapsulation efficiency of ofloxacin-loaded alg-chi nanogel was 74.4 ± 4.92%. The loading capacity of ofloxacin-loaded alg-nanogel and alg-chi nanogel were 3.9 ± 0.71% and 3.1 ± 0.47%, respectively. The results showed that the swelling of chi-alg nanogel after 5 min soaking in phosphate buffer (pH 7) was 81 ± 12.75%. Also, alg-nanogel disappeared quickly after soaking in phosphate buffer pH 7.

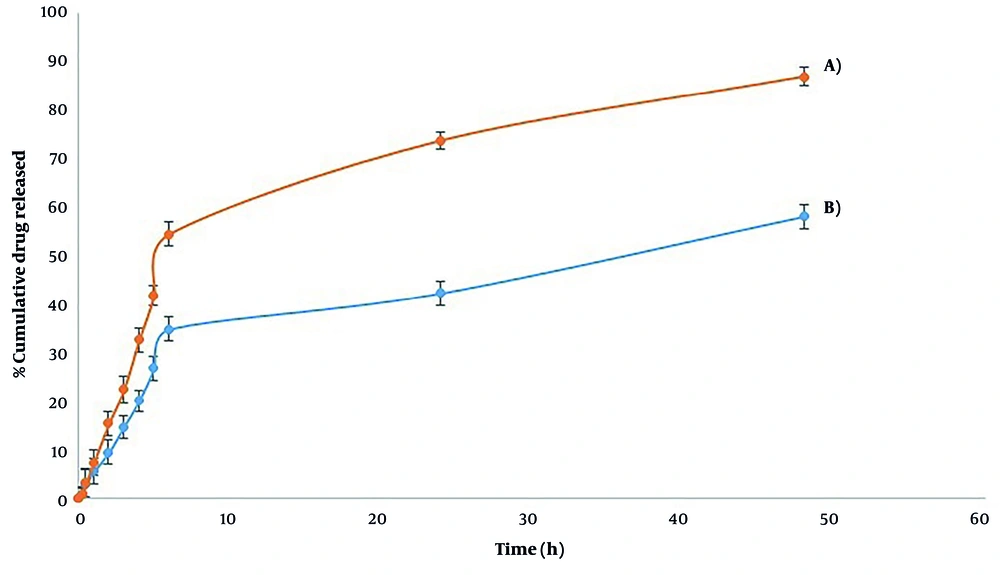

The release of ofloxacin from alg-NG at pH 7.4 at 1, 6, and 24 hours was 7.3 ± 2.69%, 54.5 ± 2.56%, and 73.8 ± 1.81%, respectively. Ofloxacin loaded in alg-chi NG was released more slowly. The release of ofloxacin from alg-chi nanogel at 1, 6, and 24 hours was 5.4 ± 2.62%, 34.8 ± 2.51%, and 42.3 ± 2.49%, respectively. After 48 h, 87 ± 1.81% and 58 ± 2.46% ofloxacin was released from the alg-nanogel and alg-chi nanogel, respectively (Figure 4).

The R² adjustment was used for considering the in vitro kinetic release of these two nanogels (Table 1). The best-fit model for alg-nanogel was Higuchi with 0.9106 R² adjusted. In vitro, the kinetic release of alg-chi nanogel was more fitted to the Higuchi model, in which the R² adjusted was 0.9221 (Figure 5).

| Formulation | Zero-Order R2 | First-Order R2 | Hixon-Crowell R2 | Higuchi R2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alg-NG | 0.7374 | 0.8304 | 0.3518 | 0.9106 |

| Alg-Chi NG | 0.7696 | 0.8604 | 0.3934 | 0.9221 |

Abbreviations: Alg-NG, alginate nanogel; Alg-Chi NG, alginate-chitosan nanogel.

5. Discussion

In this study, Alg-NG was prepared with a 4% alginate concentration. The ofloxacin-loaded alg-nanogel had a 70 nm hydrodynamic diameter, and the ofloxacin-loaded alg-chi nanogel had a 150 nm hydrodynamic diameter with a relatively broad distribution. Using 2% alginate concentration for the nanogel preparation did not result in nanogel formation. The M/G ratio of alginate affects the physical and chemical properties of the alginate structure to bind with other compounds; G residues have more affinity for binding ions, which causes the strength of the reaction. Alginate used in this study had more M residues, so to make nanobeads, a higher alginate concentration was needed (7, 19). Paques et al. (20) explained that acid is necessary for solubilizing calcium carbonate in an acidic medium during the preparation of alginate nanoparticles. A 2.5 molar ratio of acetic acid/calcium carbonate produced a formulation with higher encapsulation efficacy, explained by a greater extent of alginate gelation (17). Increasing calcium concentration caused a higher availability of calcium ions for reaction between calcium ions and alginate, so faster gelation occurred. It could determine the degree of gelation and affect sphere size (21). Hence, by increasing the molar ratio of acetic acid/calcium carbonate to 3 in the nanobeads formulation, a smaller alg-nanogel was prepared with a mean hydrodynamic diameter of 70 nm.

Kyzioł et al. (21) stated that the optimum pH for incorporating alginate with chitosan by polyelectrolyte complex is approximately 4.5, which should be maintained throughout the reaction process. This is because the pKa of sodium alginate is around 4, while the pKa of chitosan is around 6.5. Hence, a pH of 4.8 was chosen for the incorporation of Alg-NG with chitosan, as also mentioned in the alginate-chitosan synthesis.

Sorasitthiyanukarn et al. (22) prepared alginate/chitosan nanoparticles in the presence of calcium chloride at a mass ratio of 0.04:1 chitosan/alginate without further modification. Alginate/chitosan nanoparticles had a 233 nm size with a negative surface potential. In this study, when chitosan was added directly into an aqueous medium containing Alg-NG, in the case of tripolyphosphate as a crosslinker or without modification, microparticles were prepared (data not shown). This size enlargement might be because of the higher viscosity of the alginate concentration during nanogel preparation (4%), which resulted in microparticles after decoration with chitosan. Dispersing the chitosan into an oily medium containing Span80 caused the chitosan to have more time to be in proximity to nanobeads, so most of the particles were in the nano range. Several methods were used to incorporate chitosan into the Alg-NG, including the reaction of alginate and chitosan with or without tripolyphosphate in different mass ratios (17), which resulted in microparticles. However, despite experimenting with various proportions of chitosan to paraffin and different concentrations of alginate to chitosan, the Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy results did not indicate the formation of a polyelectrolyte complex between alginate and chitosan, which might be due to the difference in molecular weight of chitosan or the method of preparation (21). Hence, based on preliminary studies, a ratio of 3:1 of chitosan to alginate was chosen for further experimentation.

Measuring the zeta potential is crucial for assessing the stability of nanoparticles. A high zeta potential indicates strong electrostatic repulsion between particles, which contributes to a more stable nano-system (23). The zeta potential of ofloxacin-loaded alg-nanogel had a high negative surface charge of -150 mV. The negative zeta potential of the Alg-NG formulation indicates that the quantity of carboxylic groups in alginate is adequate to sustain the stability of the nano-system against possible aggregation. The zeta potential values of the Alg-Chi NG are -16 ± 0.9 mV, which differs from the outer surface in comparison to the Alg-NG. This difference could indicate that chitosan is incorporated into the Alg-NGs through the surface by an oily medium containing Span80, resulting in the zeta potential of -16 ± 0.9 mV. The amine groups (NH₂) of chitosan changed the surface potential of nanobeads. Stable nanoparticles usually exhibit a zeta potential greater than 30 mV, as observed in Alg-NGs. However, when the zeta potential of Alg-Chi NGs decreased to 16 ± 0.9 mV, their stability was compromised, resulting in slight particle aggregation. This finding is further corroborated by the particle size measurements of the two types of nanogels. Although the nanobeads had relative stability, the negative charge of nanoparticles could influence the amount of exposure to the cell surface (22).

The field emission scanning electron microscopy images confirmed spherical structures, and the Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy analysis was considered to distinguish between Alg-NG and chitosan-coated Alg-NG. In Lawrie et al.'s study, alginate peaks were observed at 1412 cm⁻¹ and 1596 cm⁻¹, which are related to asymmetric and symmetric stretching vibrations of CO₂⁻, respectively (24). In this study, the peaks of alginate in nanogel were related to asymmetric and symmetric stretching vibrations, which were revealed at 1402 cm⁻¹ and 1598 cm⁻¹. The peak of the chitosan backbone was observed at 1590 cm⁻¹, which was associated with the amino group (NH) bending of amine and type II amide of chitosan. Also, the peaks that were observed at 1024 cm⁻¹ and 1064 cm⁻¹ are related to asymmetric stretching C-O-C of alginate (24). In Bajpai’s study (25), the peak at 1423 cm⁻¹ was associated with N-H stretching amide, and the peak at 1381 cm⁻¹ was related to the ether bond and N-H stretching in type III amide of chitosan. In this study, these peaks of chitosan powder were observed at 1419 cm⁻¹ and 1373 cm⁻¹. According to Gallardo-Rivera et al.’s study, the ionic interaction of carboxylic groups of alginates with NH₃⁺ of chitosan was sharpened in the band at 1598 cm⁻¹ in the polyelectrolyte complex of alginate and chitosan (26). Also, by interaction between the carboxylic group of alginates with the ammonium group of chitosan, the peak at 1532 cm⁻¹ was observed, which was related to electrostatic interaction between the polyelectrolyte complex of alginate and chitosan (21). Also, after forming a complex between alginate and chitosan, a new peak was observed at 1730 cm⁻¹ related to the asymmetric stretch of carboxylic acid groups as the electrostatic reaction between these two polymers (27). These peaks, detected at 1457 cm⁻¹, 1532 cm⁻¹, and 1736 cm⁻¹ in this study, confirm the polyelectrolyte complex between alginate and chitosan.

The peak at 1056 cm⁻¹ corresponds to the C-O-C stretching of the ether group of ofloxacin (28).

The encapsulation efficacy of ofloxacin in alg-nanogel was 39.2 ± 3.62%; a low logP of ofloxacin justifies this amount, as it is a hydrophilic drug. The encapsulation efficiency of ofloxacin in alg-chi nanogel was 74.4 ± 4.92%. This result was similar to the encapsulation efficiency in Kyzioł et al.'s study. During the alginate-calcium reaction in Alg-NG preparation, a loose network may cause leakage of ofloxacin, a hydrophilic molecule, through pores. Hence, using chitosan could reduce the permeability of the nanogel and improve its mechanical properties (21). Increasing the encapsulation efficiency of alg-chi nanogel could be due to the higher viscosity of chitosan-coated alg-nanogel, which might cause faster solidification and enhance drug entrapment (18).

The strength of linkage between molecules of alginates affects the swelling process (18, 29); the linkage was weak in ofloxacin-loaded alg-nanogel, so this nanogel quickly disappeared. The deprotonation of alginate functional groups of freshly prepared Alg-NGs at pH 7 leads to a high anionic charge density. This charge exhibits electrostatic repulsive forces, which increase and expand the volume of the nanogels. As a result, rapid swelling occurs, and Alg-NGs disappear (30). Using freshly prepared nanogels can accelerate penetration of fluid to the polymeric gel, leading to quick relaxation of the macromolecular chain (18). To modify the swelling behavior, chitosan is decorated onto the Alg-NG, making freshly prepared Alg-Chi NGs. The interaction between the functional groups of chitosan and alginate delays the swelling process, resulting in only 80% swelling after 5 min soaking in phosphate buffer pH 7.

The release profile of ofloxacin from nanogels was a biphasic pattern. 54.5 ± 2.56% of ofloxacin loaded in Alg-NG was released at phosphate buffer pH 7, while 34.8 ± 2.51% ofloxacin was released from Alg-Chi NG until 6 h. This initial burst release is attributed to the ofloxacin from the surface of gels. After 48 h, the percentage of entrapped ofloxacin that was released from Alg-NG and Alg-Chi NG was 87 ± 1.81% and 58 ± 2.46%, respectively. It seems that the incorporation of chitosan and alginate with a polyelectrolyte complex created a condensed gel that decreased the release rate of ofloxacin from the formulation. In Singh et al.'s study (10), the percentage of drug release from chitosan/Alg-NG at pH 7.4 till 6 h and 72 h was 29% and 53%, respectively, which was similar to the findings of this study. The R² adjustment was used to consider the in vitro kinetic release of these two nanogels. The best-fit model for alg-nanogel was Higuchi with 0.9106 R² adjusted. In vitro, the kinetic release of alg-chi nanogel was more fitted to the Higuchi model, in which the R² adjusted was 0.9221.

5.1. Limitation

This study lacks any cellular or in vivo studies.

5.2. Conclusions

Ofloxacin-loaded Alg-NG was prepared through the emulsification/internal gelation method using calcium carbonate. According to chitosan properties, which have antibacterial and mucoadhesive properties, it has been incorporated with alginate in the nanogel structure. So, in addition to the chelate reaction between alginate and divalent cations, such as calcium, to make a nanogel, polyelectrolyte complexes between the amine group of chitosan and the carboxylic alginate group lead to a polyelectrolyte complex. By adding paraffinized chitosan into Alg-NG, it took more time for the interaction rate between alginate and chitosan; subsequently, the Alg-Chi NG's size was slightly increased. Ionic interaction between alginate and chitosan condenses the nanogel, so it decreases the rate of ofloxacin release in comparison to Alg-NG separately, which could enhance retention of alg-chi nanogel on tissue. The kinetic model of alg-chi nanogel followed the Higuchi model; R² is adjusted to 0.9221, which explained that diffusion and erosion made an impact on the release of ofloxacin from nanogel, as the kinetic model of ofloxacin release from alg-nanogel was similar to alg-chi nanogel. According to the results of this study, it seems that ofloxacin-loaded alg-chi nanogel could have a desirable effect on ocular infection.