1. Background

The accelerated growth of industrial operations has led to the extensive release of synthetic dyes into water bodies, raising serious environmental and health concerns (1). Methylene blue (MB), a widely used cationic dye in the textile and pharmaceutical sectors, is especially troublesome due to its stability and resistance to standard wastewater treatment processes (2). Consequently, there is a growing need to develop cost-effective, sustainable, and efficient adsorbent materials for removing such dyes from contaminated water. A wide range of different removal techniques used to clean wastewater containing MB dye are described in the literature (3). The removal of the pollutant MB from wastewater produced by the printing, paper, textile, and other sectors has been studied (4). To eliminate colors from wastewater, a number of physical, chemical, and biological techniques have been developed (5). Adsorption is a commonly used approach that is thought to be straightforward and easy to utilize among the many ways available for the removal of environmental pollutants (6, 7). The main advantage of adsorption techniques is that they do not create toxic byproducts that could cause secondary contamination. The adsorbent must have a high pore volume, a large surface area, and the right surface functionalities for any adsorption process to be successful. Accordingly, scientists have created a number of porous materials, including metal-organic frameworks, zeolites, activated carbon, pillared clays, mesoporous oxides, and polymers, to adsorb harmful contaminants in the air, water, and land (7-10).

The most promising biomedical materials are electrospun nanofibers. One method of fabrication is electrospinning (11). The most promising biomedical materials are electrospun nanofibers. One method of fabrication is electrospinning (12). The three primary parts of an electrospinning system are a grounded collector plate, a spinneret, and a high-voltage power source. Usually, the spinneret is a metallic needle that is fastened to a syringe that contains a molten polymer for melt electrospinning or a polymer solution for solution electrospinning (13). Numerous polymeric materials, whether synthetic, natural, or both, can be used to create nanofibers (14). Although synthetic polymers provide more flexibility in their manufacture and modification, natural polymers are known to have superior biocompatibility. Collagen, laminin, fibroin, elastin, chitosan (Chi), gelatin, pectin, and agarose are examples of natural polymers that are utilized in electrospinning (15).

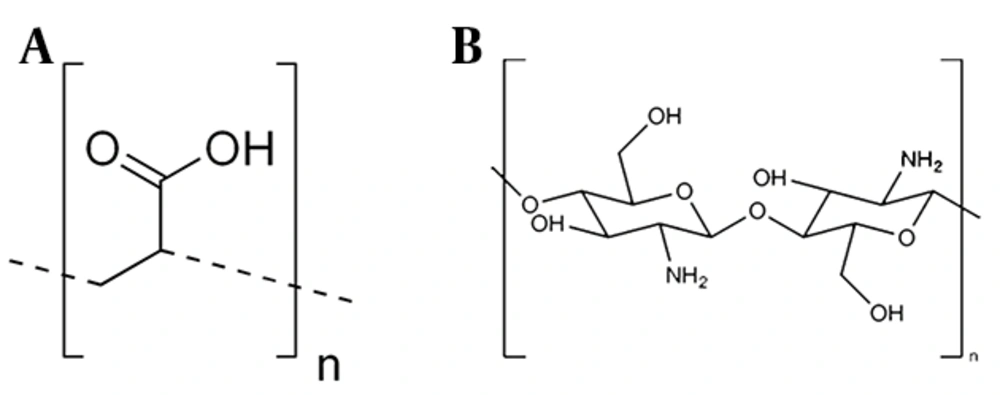

Chitosan is a natural cationic biopolymer and linear polysaccharide composed of N-acetyl-D-glucosamine and D-glucosamine units connected by β-1,4-glycosidic linkages. Obtained from chitin through demineralization and deproteinization, it has an extensive array of medical and agricultural applications (16). Chitosan has functional groups strategically placed to provide these unique polysaccharide qualities (17). An amino group enhances Chi’s functional and structural features at the C-2 position of the glucosamine unit. This amino group is responsible for its cationic nature and confers antibacterial action. This polymer has biocompatibility and nontoxicity, but its poor mechanical properties and the difficulty in electrospinning have led to it being reinforced with synthetic polymers (18, 19).

Polyacrylic acid (PAA) is a synthetic polymer with a high molecular weight and good water solubility, synthesized from acrylic acid monomers. In addition to its use in creating cross-linked polymers, PAA is also used to make polymeric blends and nanocomposites (20). The fact that PAA is a water-soluble, non-toxic, biodegradable, and biocompatible substance is just one of its many benefits (21, 22). By adding polymeric modifiers to increase its strength or cross-linking to create a stable structure, PAA’s mechanical qualities can be enhanced (20). Additionally, cross-linked PAA has a high water-absorption capacity, excellent optical properties, and weather resistance. For example, the chemical cross-linking of PAA with Chi forms a gel-like structure known as PAA-graft-Chi (23). Its hydrophilicity provides the cross-linked polyacrylate PAA with a high level of adhesiveness and a high water-absorption capacity, capable of retaining 100 times its weight of water, far surpassing the performance of more ordinary hydrophilic polymers (24).

Because of their easy production, customizable surface functionality, and high surface area-to-volume ratio, electrospun nanofibers have become attractive options for environmental remediation. Specifically, synergistic interactions can be used to improve adsorption performance in polymeric composites made of natural and synthetic polymers. Because of electrostatic and hydrogen bonding interactions, PAA, a synthetic polymer with a large number of carboxylic functional groups, has a good adsorption capability. Because of its amino and hydroxyl groups, Chi, a biopolymer made from chitin, has a strong inherent attraction for a variety of contaminants and is known to be biodegradable and biocompatible.

To effectively remove MB from aqueous media, electrospun polyacrylic acid-chitosan nanofibers (PAA-Chi NFs) were created and characterized in this work. In order to improve the nanofibers’ adsorption properties and increase their viability as efficient adsorbents of MB and other organic pollutants, Chi was strategically included into the PAA matrix. To assess the structural, compositional, and rheological properties of the produced nanofibers, a thorough examination was carried out. The addition of Chi to the PAA framework enhances the nanofibers’ adsorption capabilities, making them suitable for wastewater treatment. The results can be applied to the development of sustainable, biocompatible materials to address the issue of water contamination. By offering a workable method for purifying dye-contaminated water, the current work advances environmentally friendly remediation technology.

2. Methods

The PAA (molecular weight ~250,000 Da, CAS: 24980-41-4) and Chi (high molecular weight, degree of deacetylation (DDA) > 75%, molecular weight range 100,000 - 300,000 Da, CAS: 9012-76-4) were obtained from Areej Al-Furat Co., Baghdad, Iraq (Figure 1). Glacial acetic acid and sodium hydroxide (NaOH, 98%) were purchased from Albaher Co., Baghdad, Iraq. All chemicals and analytical reagents were used as received. The DDA directly determines the number of free amino groups available for interaction with PAA carboxyl groups and MB molecules. Studies have shown that Chi with DDA > 75% provides an optimal balance between solubility, mechanical properties, and adsorption capacity. The molecular weight range specified ensures adequate chain entanglement for stable fiber formation while maintaining sufficient functional group density for effective adsorption.

2.1. Preparation of Polyacrylic Acid-Chitosan Electrospinning Nanofibers

In order to ensure the creation of homogeneous and functional nanofibers suitable for advanced applications, the electrospinning process for producing PAA-Chi NFs in a 70:30 ratio required several distinct steps. Electrospinning is a versatile technique for fabricating polymeric fibers with diameters in the nano- to microscale range, offering high surface area and porosity — two characteristics essential for applications in biological and environmental fields. Initially, individual solutions of PAA and Chi were prepared. Chitosan, which is soluble only under acidic conditions, was dissolved in a 2% (v/v) acetic acid solution to a concentration of 15% (w/v). Concurrently, PAA was dissolved in deionized water at a similar concentration. Both solutions were stirred thoroughly at room temperature until complete dissolution was achieved. The two polymer solutions were then mixed (weight ratio of 70:30 of PAA to Chi) after dissolution. This mixed solution was further stirred for several hours to achieve homogeneity and prevent phase separation. Viscosity, conductivity, and pH of the final blend were measured and adjusted as necessary. The pH was adjusted to 4 - 5 to ensure that the Chi remained soluble in the presence of PAA, and the viscosity was tuned to enable continuous fiber formation during electrospinning (25). The homogeneous polymer blend was loaded into a syringe with a metallic needle. The electrospinning system consisted of a high-voltage power supply, a syringe pump, and a grounded collector. A voltage of 25 kV was applied between the needle and the collector, which were positioned 15 cm apart. The flow rate of the polymer solution was set to 1.5 mL/h. The polymer solution was extruded from the needle tip under the influence of the electric field, forming a jet that was elongated and solidified into nanofibers as the solvent evaporated (26).

2.2. Physicochemical Characterization of Nanofibers

The synthesized nanofibers were characterized to confirm their morphology, composition, and functional properties. Fiber diameter, uniformity, and surface morphology were assessed using Field Emission Scanning Electron Microscopy (FESEM). The presence of PAA and Chi was confirmed by Fourier-transform infrared (FTIR) spectroscopy, and chemical interactions between PAA and Chi were detected. Additional analyses, including viscosity and rheological behavior, were also performed as required for the intended application. This process demonstrated that the fabrication of PAA-Chi NFs by electrospinning necessitated meticulous preparation of the polymer solution, fine-tuning of electrospinning parameters, and subsequent characterization, enabling the production of nanofibrous materials with tailored properties for diverse scientific and technological applications.

2.3. Zeta Potential

Using a Malvern Zetasizer (Malvern Instruments, UK), the zeta potential of the PAA-Chi NFs was determined to monitor changes in surface charge. A suspension was prepared by ultrasonically dispersing nanofibers in DMSO (0.01 g/100 mL) for evaluation. All measurements were conducted at room temperature.

2.4. Rheological Behavior

The rheological properties of the nanofiber solutions were measured using a rheometer. The viscoelastic and viscosity characteristics of PAA-Chi solutions (30% Chi) were evaluated at various temperatures and shear rates (27). The rheological test results provided insights into the solutions’ viscoelastic properties and flow behavior, indicating their suitability for the electrospinning process.

2.5. Dye Adsorption Measurement of Composite

The adsorption properties of the composite were systematically evaluated using a batch equilibrium technique under controlled environmental conditions. Experiments were conducted at room temperature (25°C), with agitation maintained at 100 rpm on an orbital shaker to ensure uniform mixing and minimize mass transfer limitations. For each experiment, a precisely weighed dry sample of the composite (10 ± 0.0001 mg) was immersed in 50 mL of 100 mg/L MB dye solution at pH 6. After the adsorption process, the composite was separated from the solution by filtration. The remaining dye concentration in the supernatant was determined using a UV-visible spectrophotometer (UV-1800, Shimadzu, Japan) at a wavelength of 664 nanometers, corresponding to the peak absorbance of MB. To ensure accurate concentration measurements during the adsorption experiments, a calibration curve for MB was established based on its λmax of 664 nm. Equations 1 and 2 were used to calculate the adsorption capacity (qe) of the SA/G-NH and the dye removal efficiency (R) (Equations 1 and 2):

qe refers to the adsorption capacity (mg/g) of PAA-Chi NFs. Co and Ce refer to the concentrations (mg/L) of the initial and equilibrium dyes, respectively. V and W refer to the solution volume (L) and the dry weight of the PAA-Chi NFs adsorbent (g), respectively.

2.6. Determination of Calibration Curve

To determine the standard calibration curve for MB dye, a series of standard solutions (0 - 100 mg/L) of MB dye were prepared. The resulting solutions were analyzed using a UV-Vis spectrophotometer at a wavelength of 664 nm. The absorbance values of the prepared solutions were recorded, and the absorbance values were plotted against the concentration to obtain the standard calibration curve. The calibration curve demonstrated very good linearity, with a coefficient of determination (R2) value of approximately 0.989. Therefore, it is highly likely that the concentration measurements obtained during the adsorption experiments were accurate and reliable.

2.7. Quality Assurance and Quality Control

To ensure the reliability and reproducibility of the results, all adsorption experiments were conducted in triplicate, with the data presented as mean values ± standard deviation. Control experiments using blank samples, which contained MB in distilled water without the adsorbent, were analyzed to confirm the absence of interferences. The spectrophotometer was routinely calibrated with standard solutions, and the baseline was adjusted prior to each measurement series to maintain analytical accuracy.

2.8. Kinetic Model Fitting of Dye Adsorption

To gain a better understanding of the adsorption kinetics of MB onto the PAA-Chi composites, two common kinetic models, specifically the pseudo-first-order and pseudo-second-order models, were employed. These models are represented by Equations 3 and 4, respectively (28, 29):

The quantity of MB adsorbed at equilibrium is denoted by qe (mg/g), while the amount adsorbed at a given time, t, is represented by qt (mg/g). The kinetics of this adsorption process were evaluated using non-linear pseudo-first-order and pseudo-second-order models, for which the rate constants are K1 (min-1) and K2 (g/mg×min), respectively. The pseudo-first-order model, as first described by Lagergren, presupposes that the rate of adsorption is directly proportional to the difference between the equilibrium adsorption capacity and the amount adsorbed at any time t. This model is generally considered applicable to the initial stages of physical adsorption or to processes occurring on surfaces with low adsorbate coverage.

2.9. Isotherm Model Fitting of Dye

The Langmuir model and Freundlich isotherm model were applied to study the equilibrium adsorption isotherm of the polyacrylic acid-chitosan nanocomposite (PAA-Chi NC), as shown in Equations 5 and 6 (28):

KL and q0 are Langmuir isotherm constants that represent the adsorption rate and the adsorption capacity, respectively. Freundlich constant (Kf) (L/g) and 1/n are Freundlich constants, where Kf indicates adsorption capacity and 1/n indicates the intensity of adsorption.

3. Results

3.1. Fabrication and Characterization of Polyacrylic Acid-Chitosan Nanofibers

Recent research has focused on nanofibrous materials because of their high specific porosity, surface area, and adjustable structural properties. Electrospinning produces nanofibers from various polymer mixtures precisely and efficiently. Due to several fundamental factors, electrospinning PAA-Chi composite nanofibers has become significant. The goal was to employ PAA and Chi to create a material with enhanced MB adsorption. Electrospinning is ideal for fabricating practical materials due to its adaptability and customization.

3.2. Fourier-Transform Infrared Spectroscopy Study

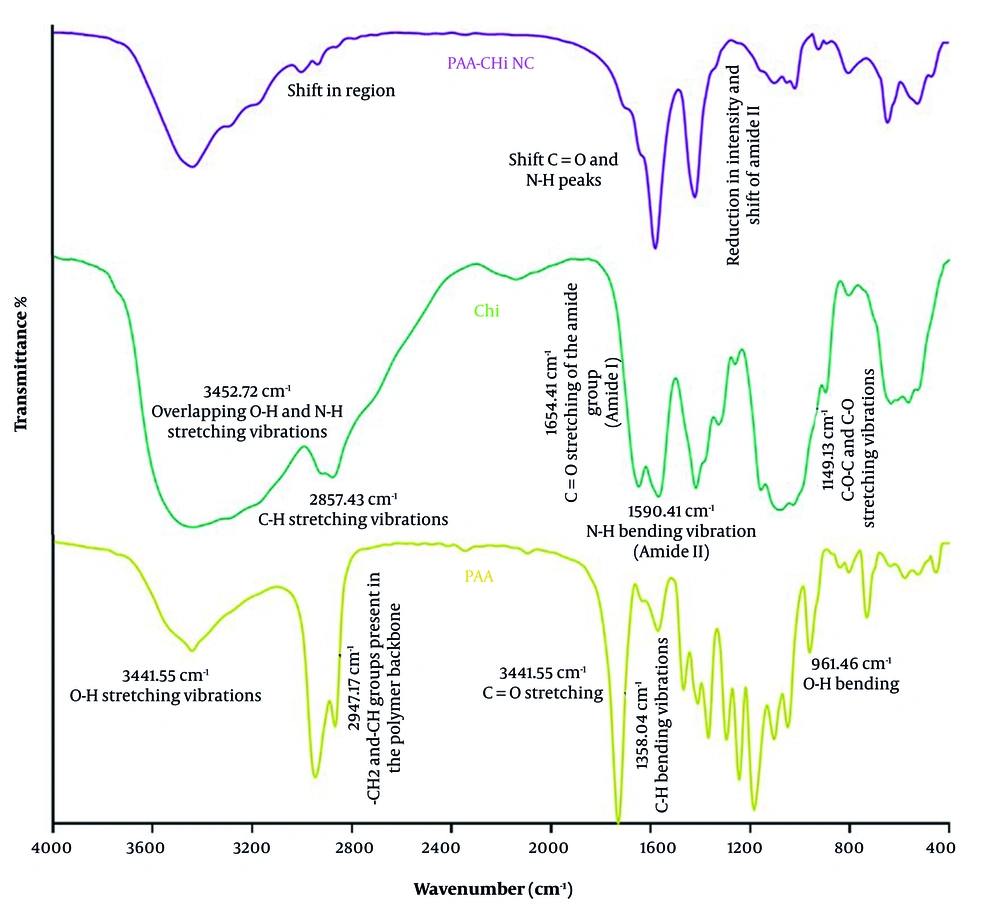

The FTIR spectra, which confirm the successful interaction between PAA and Chi, are presented in Figure 2 for both PAA, Chi, and the synthesized PAA-Chi NFs. In the spectrum of pure PAA, a broad band at 3441.55 cm-1 corresponds to O-H stretching vibrations, while a specific peak at 1730.20 cm-1 is due to C=O stretching of carboxylic groups. The band at 2947.77 cm-1 reflects the stretching vibrations of –CH2 and -CH groups within the polymer backbone. The Chi spectrum exhibits a broad band at 3452.72 cm-1 due to overlapping O-H and N-H stretching vibrations, indicative of extensive hydrogen bonding. Peaks at 1654.41 cm-1 and 1590.41 cm-1 correspond to C=O stretching (amide I) and N-H bending (amide II) of the residual acetyl groups, respectively. The C-H stretching appears at 2857.43 cm-1, and 1403.3 cm-1 corresponds to C-N and C-O stretching vibrations.

In the FTIR spectrum of the PAA-Chi NC, noticeable shifts and reductions in intensity were observed in the characteristic bands of both polymers. The O-H and N-H stretching region shows a shift, indicating the existence of hydrogen bonds between the carboxylic groups of PAA and the amino/hydroxyl groups of Chi. Additionally, the C=O stretching peak of PAA and the amide I/II bands of Chi exhibit shifts and intensity changes, further confirming the interaction. These spectral modifications support the formation of a new intermolecular network between PAA and Chi through hydrogen bonding and possible electrostatic interactions, contributing to the structural integrity and enhanced functionality of the nanofibers.

The enhanced structural integrity and adsorption performance of the PAA-Chi NFs are the result of several key combined interactions. Hydrogen bonding is the predominant interaction, occurring between the PAA carboxyl groups (proton donors) and the Chi amino and hydroxyl groups (proton acceptors), which creates a stable intermolecular network. Simultaneously, under acidic electrospinning conditions (pH 4 - 5), electrostatic attraction contributes to complex formation, as the Chi amino groups become protonated (-NH3+) while some PAA carboxyl groups remain ionized (-COO-). Finally, chain interpenetration — the physical entanglement of the PAA and Chi polymer chains — further contributes to mechanical stability and functional integration. These combined mechanisms ensure that the functional groups from both polymers remain accessible for MB binding while the composite structure maintains its mechanical robustness.

Comparative FTIR analyses of polymeric systems confirm strong intermolecular interactions in PAA-Chi-based materials. In polycaprolactone-chitosan (PCL-CH) nanofibers, peak modifications were attributed to interpolymer bonding and molecular compatibility (25). Similarly, PAA-Chi hydrogels exhibited broad absorption bands (3000 - 3600 cm-1, O-H/N-H stretching) and characteristic peaks at 1637 cm-1 (C=O stretching) and 2921 - 2854 cm-1 (C-H stretching), indicating hydrogen bonding and network formation (30). In PAA-Chi nanoparticles, a decrease in amide I (1662 cm-1) and amide II (1586 cm-1) intensities, along with new peaks at 1731 cm-1 (C=O of PAA) and 1628 cm-1 (NH3+ of Chi), further confirmed polyelectrolyte complex formation through electrostatic interactions (31). Collectively, these results demonstrate that combining PAA with Chi produces stable polymeric networks with enhanced structural stability and functional performance, validating the synthesis of the PAA-Chi NC in this study.

3.3. Field Emission Scanning Electron Microscopy Analysis

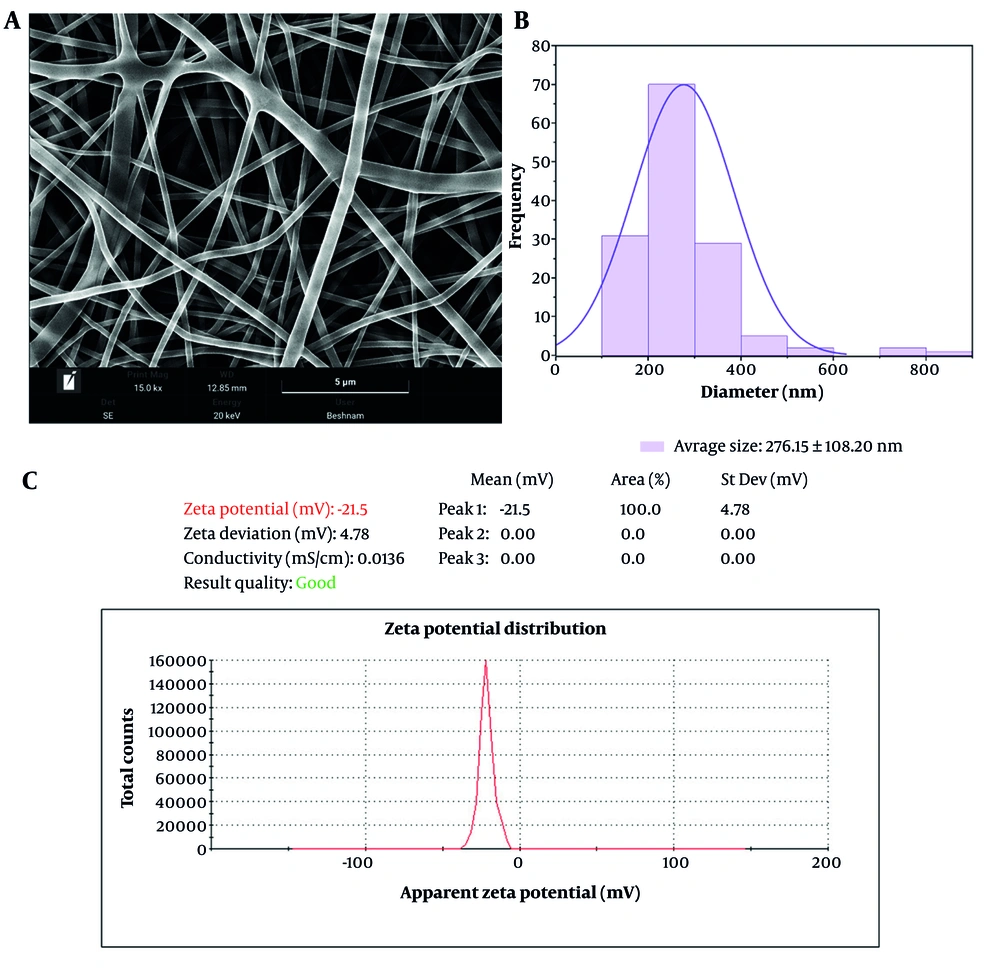

Figure 3A and B presents the FESEM images of the nanofibers, accompanied by their corresponding diameter distribution histograms. All specimens exhibit a uniform and bead-free morphology, indicative of a well-controlled fabrication process. The as-spun PAA-Chi 30% nanofibers appeared with a fairly smooth surface and an average diameter of 276.15 ± 108.20 nm. Very smooth and continuous surfaces of the PAA-Chi NFs are highly desirable properties since they can be used in various applications, such as adsorption processes.

It was found that the average reported diameter of about 276 nm is in the nanoscale range targeted during fabrication and provides a high surface area-to-volume ratio, which is favorable for applications that rely on effective surface interactions. The application of FESEM revealed that the morphology of the nanofibers is uniform and advantageous, specifically noting the smooth surface of PAA-Chi NFs. These findings together show that these nanofibers are suitable candidates for various adsorption processes, such as the removal of MB from aqueous solutions. The diameter variation can be accounted for by changing parameters during processing, such as solution viscosity, concentration, flow rate, and ambient conditions, all of which influence fiber morphology. More importantly, fiber diameters significantly affect the functional performance of nanofiber membranes: Smaller diameters usually improve filtration and adsorption efficiency due to the increase in surface-to-volume ratio and decrease in pore size (32).

3.4. Zeta Potential Characterization

Figure 3C presents the zeta potential distribution of the synthesized PAA-Chi NFs. The measured zeta potential value was -21.5 mV, with a standard deviation of ± 4.78 mV and a conductivity of 0.0136 mS/cm. The distribution curve exhibits a single, narrow peak centered at -21.5 mV, indicating a uniform and stable surface charge across the nanoparticle dispersion. The observed negative surface charge can be attributed primarily to the ionized carboxyl groups (-COO-) of PAA, which dominate the particle surface, despite the presence of protonated amino groups (-NH3+) from Chi. This suggests successful surface modification and interaction between the two polymers. The moderate stability range (± 20 to ± 30 mV) is where the measured zeta potential of -21.5 mV falls, which presents significant issues for long-term use in aqueous systems. Higher zeta potential levels (above ± 30 mV) are typically chosen for improved colloidal stability and prevention of nanofiber aggregation during prolonged use, even if this value is adequate to prevent rapid aggregation under ambient circumstances (33).

Nonetheless, for several reasons, the modest stability of PAA-Chi NFs may be suitable for real-world wastewater treatment applications. The adsorption process takes place over comparatively short contact times (8 hours to equilibrium); the negative surface charge is still favorable for electrostatic attraction with cationic MB dye; initial observations during repeated batch experiments showed no visible aggregation of the nanofiber structure; and the nanofibers are used as a fibrous mat rather than a suspended colloidal system, reducing aggregation concerns.

3.5. Rheological Behavior Analysis

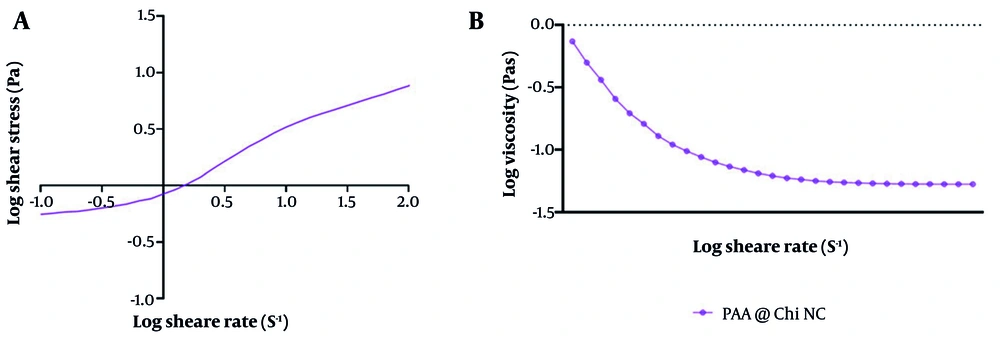

The rheology of PAA-Chi nanofiber formation has been systematically tested to understand its flow properties. The variations in shear stress (Pa) and apparent viscosity (Pas) with shear rate (s-1), as presented in Figure 4, are as follows. As demonstrated in Figure 4A, shear stress gradually and nearly linearly increases throughout the total tested shear rate range, indicating that it has a stable rheological response without sudden fluctuation when the input is perturbed. The uniform increment in shear stress with respect to the applied force implies an internal structure that appears homogeneous and exhibits strong intermolecular interactions between both PAA and Chi chains, responsible for such consistent deformation.

In addition, Figure 4B shows that the apparent viscosity decreases significantly as the shear rate increases, demonstrating typical shear-thinning behavior. This confirms that the PAA-Chi formulation is pseudoplastic, whereby the viscous effects decrease with higher shear conditions. Such rheology is favorable during a dynamic process like electrospinning, where low viscosity compensates for elongation in the polymer jet and fiber formation. The observed flow pattern implies that the PAA-Chi nanofiber solution exhibits fluid-like characteristics under high shear rates, enhancing its spinnability and uniformity. This is particularly important in ensuring continuous fiber production with controlled morphology.

As supported by previous findings, the viscosity-shear rate profile plays a key role in determining the electrospinning ability and final fiber properties of polymer blends (34). Ultimately, the rheological stability, combined with predictable shear stress and viscosity behavior, highlights the suitability of the PAA-Chi system for nanofiber production. The ability to tailor viscosity in response to shear rate variations allows for better process control, which is critical for producing uniform and functional electrospun nanofibers.

These observations align well with prior studies on Chi-based systems. Chitosan solutions are consistently reported to exhibit pronounced shear-thinning behavior across various temperatures and concentrations, attributed to polymer chain disentanglement under shear (35). Similarly, cellulose- Chi mixtures developed in ionic liquids were found to be pseudoplastic liquids, and the viscosity of the mixture reduced with the Chi content, supporting the understanding that strong polymer-polymer interactions regulate rheology (36).

Collectively, the rheological characteristics of the PAA-Chi formulation, which include its steady rise in shear stress and pronounced shear-thinning effect, can be ascribed to the existence of strong interchain interactions and pseudoplasticity. These properties are necessary to make nanofibers mechanically stable and free of defects, these properties support the appropriateness of the formulation for dye adsorption tasks.

3.6. Adsorption Uptake of Methylene Blue

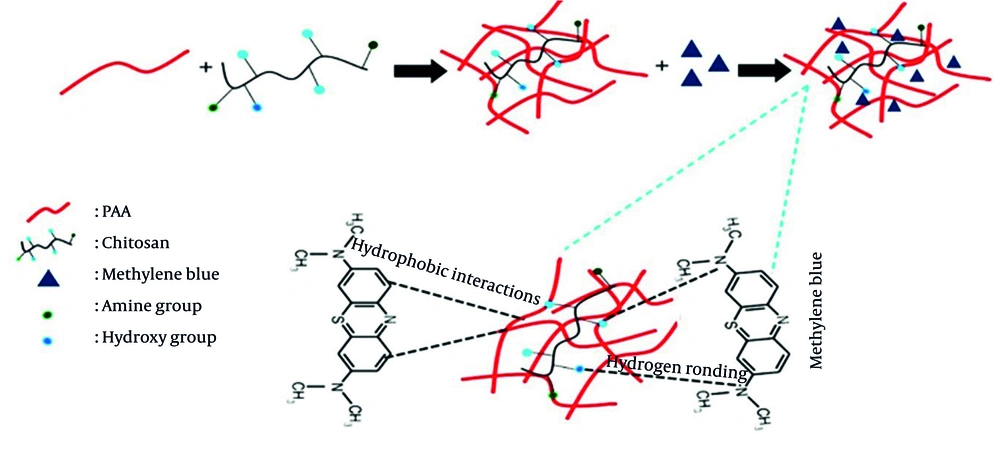

The obtained results of adsorption show that the hybrid network of PAA and Chi exhibits high efficiency in removing MB dye from aqueous media. This performance is attributed to the three-dimensional polymeric network formed through the physical interpenetration of the two polymer chains (37). The amine (-NH2) and hydroxyl (-OH) groups of Chi and the carboxyl (-COOH) groups of PAA are central to the adsorption process (37, 38). These groups facilitate strong bonding of MB molecules via hydrogen bonds, while the negatively charged carboxyl groups and the positively charged dye interact through electrostatic attraction. Additionally, adsorption is further stabilized by hydrophobic interactions between the aromatic nuclei of MB and the non-polar regions of the network (39, 40). The main interactions between the dye and the adsorbent — hydrogen bonding and hydrophobic interactions — indicate a multimodal adsorption mechanism (39).

The process of adsorption of MB onto PAA-Chi nanofiber formation is a complex process governed by the physicochemical properties of the dye and the nanofibrous surface. Chitosan and PAA together form a nanofiber matrix characterized by structural stability, uniformity, and porosity, which highly favor the process of dye adsorption (25, 41, 42). The combination of Chi and PAA not only improves adsorption performance but also provides better structural stability to the nanofibers during the adsorption process (25, 43). The MB is adsorbed onto PAA-Chi NFs due to the combined effects of hydrogen bonding reactions and the unique surface characteristics of the three-dimensional nanofiber structure (25, 44). Understanding these aspects is crucial for optimizing nanofibers for their effective use as adsorbents for cationic dyes, such as MB. The hydrophobic zone facilitates interaction with the hydrophobic domains of the nanofibers, thereby promoting the adsorption process, as shown in Figure 5. The schematic illustrates how PAA-Chi nanofiber composites are fabricated by electrospinning and describes their mechanism for adsorbing MB.

The adsorption mechanism of polyacrylic acid-chitosan nanofibers (PAA-Chi NFs) (25)

High-performance metrics such as the 78.125 mg/g adsorption capacity, pseudo-second-order kinetics, and Langmuir isotherm fit (R2 = 0.9789) are explained by the resulting nanofibers, which possess a negatively charged surface (-21.5 mV) and a high surface area. These nanofibers employ a multi-modal binding strategy, primarily involving electrostatic attraction between the MB cation and the deprotonated carboxyl groups of PAA, augmented by hydrogen bonding and hydrophobic interactions. According to recent research, the introduction of Chi into the polycaprolactone (PCL) matrix enhances the porosity and surface area of the nanofibers, providing additional sites for adsorption and accelerating the overall process. Additionally, the amino groups in Chi are pH-responsive: They are protonated under acidic conditions, leading to positive surface charges and potential electrostatic repulsion with MB, while in alkaline environments, deprotonation reduces this repulsion and promotes stronger adsorption. The structural compatibility of Chi with PCL is also improved by hydrogen bonding between its amino groups and the carbonyl (C=O) groups of PCL, resulting in a mechanically stable and cohesive nanofiber network. This synergy not only maintains structural integrity during adsorption but also significantly enhances performance, with higher Chi contents (30% w/w) achieving more than a fourfold increase in MB adsorption capacity compared to pure PCL, due to the greater number of active sites and improved surface properties (25).

Another study confirmed that Chi in the PAA- Chi nanofiber system enhances MB adsorption by providing amino and hydroxyl groups for hydrogen bonding and electrostatic interactions, increasing hydrophilicity and surface reactivity, and forming a stable network with PAA via -NH3+/COO- attraction. These features increase the number of active sites, improve stability, and significantly boost adsorption capacity (45). Accordingly, the findings confirm that the PAA-Chi material possesses favorable physicochemical properties that qualify it as a promising candidate for the treatment of industrial wastewater contaminated with organic dyes. Its bio-based nature and reusability add significant economic and environmental advantages to its use in sustainable remediation applications.

3.7. Effects of Original Methylene Blue Solution pH and Concentration

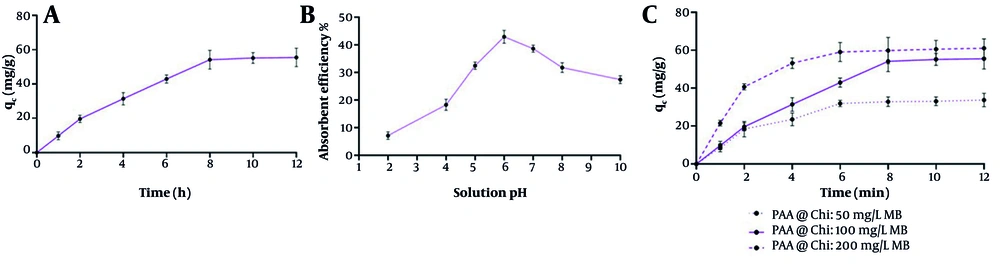

The results shown in Figure 6A demonstrate that the adsorption efficiency of MB dye by the PAA-Chi NFs gradually increases with increasing contact time until equilibrium is reached after approximately 8 hours, with the equilibrium qe reaching approximately 60 mg/g. This phenomenon indicates that the adsorption process is rapid due to the large number of active sites available on the surface of the nanofibers. Over time, however, saturation leads to a gradual decrease in the adsorption rate, indicating that the process becomes dependent on the diffusion of molecules inside the fiber matrix and their binding to the active sites.

Figure 6B illustrates the effect of the solution pH on the adsorption efficiency. Efficiency was observed to increase with increasing pH, reaching a peak at pH = 6, with an adsorption rate exceeding 40%. This can be explained by the fact that a highly acidic medium leads to protonation of the binding sites in Chi, weakening the electrostatic interaction between the positively charged surface and the MB molecules, which are also positively charged. In contrast, at a neutral pH, the carboxyl groups in PAA are negatively ionized, enhancing interaction with MB via electrostatic attraction. After pH = 6, the efficiency begins to decrease again due to reduced surface activity and competition of hydroxide ions with MB molecules for active sites.

In Figure 6C, the effect of initial MB dye concentration (50, 100, and 200 mg/L) on adsorption capacity over time was studied. The highest qe was achieved at 200 mg/L, reaching over 65 mg/g, compared to 45 and 30 mg/g at 100 and 50 mg/L, respectively. This is explained by the fact that a higher dye concentration provides a greater number of MB molecules available for adsorption on the surface, increasing the concentration difference and enhancing the migration of molecules to the binding sites. However, it should be noted that increasing the concentration may eventually lead to saturation of the adsorbent surface, limiting relative efficiency over time.

Overall, these results confirm the effectiveness of PAA-Chi NFs in removing MB dye from aqueous solutions. This is attributed to the synergistic chemical composition between the hydrophobic and electrostatic functional groups of both polymers, which imparts suitable surface properties for efficient adsorption.

3.8. Kinetic Analysis

The adsorption kinetics of the PAA-Chi NC were investigated using the pseudo-first-order and pseudo-second-order models, and the results are presented in Figure 7A and B and Table 1. The pseudo-first-order model yielded a rate constant (K1) of 0.6377 min-1 and an equilibrium qe of 5.87 mg/g. The R2 for this model was 0.7007, indicating that the model did not fit the experimental data well. By contrast, the pseudo-second-order model provided a much better fit, with an R2 of 0.9859. This model yielded a rate constant (K2) of 0.0005 g/mg×min and an equilibrium adsorption capacity (q0) of 43.10 mg/g. The much higher R2 value and qe of the pseudo-second-order model indicate that this model is more suitable for explaining the adsorption kinetics of the PAA-Chi NFs.

A and B, modeling of adsorption kinetics of methylene blue (MB) dye using polyacrylic acid-chitosan nanofibers (PAA-Chi NFs) through a pseudo-first-order and pseudo-second-order model, black line representing actual results and blue line indicating predicted results; C, the adsorption isotherms simulated according to the Langmuir model; D, the adsorption isotherms simulated according to the Freundlich isotherm model.

| Variables | Curve Equation | Parameters | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kinetic-isotherm analysis | ||||

| Pseudo-first-order | y = 0.6377x - 72.314 | R2 = 0.7007 | K1 = 0.6377 (min-1) | qe = 5.87 |

| Pseudo-second-order | y = 0.0232x - 1.064 | R2 = 0.9859 | K2 = 0.0005 (g.mg-1. min-1) | q2 = 43.10 |

| Adsorption isotherm | ||||

| Langmuir | y = 0.0128x + 0.62 | R2 = 0.9789 | KL = 0.021 (L/mg) | Qm = 78.125 |

| Freundlich | y = 0.4022x + 0.9009 | R2 = 0.8599 | Kf = 1.187 | n = 2.486 |

Abbreviations: R2, coefficient of determination; K1, rate constant; KL, Langmuir constant; qe, adsorption capacity; Qm, maximum adsorption capacity.

The superior fit of the pseudo-second-order model suggests that the rate-limiting step in adsorption is likely chemisorption, which involves valency forces through sharing or exchanging electrons between the adsorbent and adsorbate. This interpretation is consistent with the chemical composition of PAA-Chi NFs, which can strongly interact with the molecules of the adsorbate.

3.9. Adsorption Isotherm

The adsorption isotherms simulated according to the Langmuir and Freundlich models are shown in Figure 7C and D. The Langmuir isotherm model exhibited an excellent fit, with an R2 value of 0.9789. The Langmuir constant (KL) was determined to be 0.021 L/mg, and the Qm was calculated as 78.125 mg/g. This high R2 value suggests that the adsorption process closely follows the Langmuir model assumptions, indicating monolayer adsorption on a homogeneous surface with a finite number of identical sites.

The Freundlich isotherm model, while still showing a good fit, had a lower R2 value of 0.8599. The Kf was found to be 1.187, and the adsorption intensity (n) was 2.486. The lower R2 value compared to the Langmuir model suggests that the Freundlich model, which assumes a heterogeneous surface with a non-uniform distribution of adsorption heat, may not be as suitable for describing the adsorption process of PAA-Chi NFs.

The better fit of the Langmuir model implies that the adsorption sites on the PAA-Chi NC nanofibers surface are likely energetically equivalent and that the adsorption is limited to a monolayer. The relatively high Qm value of 78.125 mg/g indicates that the PAA-Chi NC nanofiber has a considerable adsorption capacity, making it a promising material for various applications in adsorption processes.

A comprehensive review of PAA-Chi NFs and recently published adsorbents for the removal of MB (2019 - 2025) is shown in Table 2. Although other materials have superior capacity, the PAA-Chi NFs adsorption capacity (78.125 mg/g) performs competitively among Chi-based composites.

Abbreviations: PAA-Chi NFs, polyacrylic acid-chitosan nanofibers; Chi, chitosan.

3.10. Conclusions

Lastly, this paper describes the design, preparation, and application of electrospun PAA-Chi NFs, in 70:30 proportions, as an effective adsorbent for the removal of MB from aqueous solutions. The study highlights the paramount importance of nanofiber composition, morphology, and environmental conditions on adsorption performance. The synthesized PAA-Chi NFs exhibit a uniform morphology with no beads and desirable surface properties, as determined by systematic characterization methods such as FESEM, FTIR, and zeta potential analysis.

Adsorption studies revealed that the PAA-Chi NFs possess a high affinity for MB dye, with efficiency enhanced by electrostatic interaction and hydrogen bonding between the nanofiber surface and dye molecules. Solution pH was also found to play a major role, with higher pH levels being more favorable for adsorption. Furthermore, initial dye concentration and adsorption capacity showed a positive correlation, indicating that a higher concentration gradient promotes greater mass transfer.

These results demonstrate that PAA-Chi NFs are promising, sustainable, and effective adsorbents for treating wastewater contaminated with dye. The findings underscore the significance of material design, surface functionality, and environmental parameters in optimizing adsorption processes, which holds great promise for environmentally friendly strategies in water purification and environmental remediation.