1. Background

Flavonoids are one of the most attractive classes of bioactive substances and are found in fruits, vegetables, herbs, and beverages. This group of substances has remarkable physiological effects, and one of the most important medicinal substances in this group is naringenin (1-5).

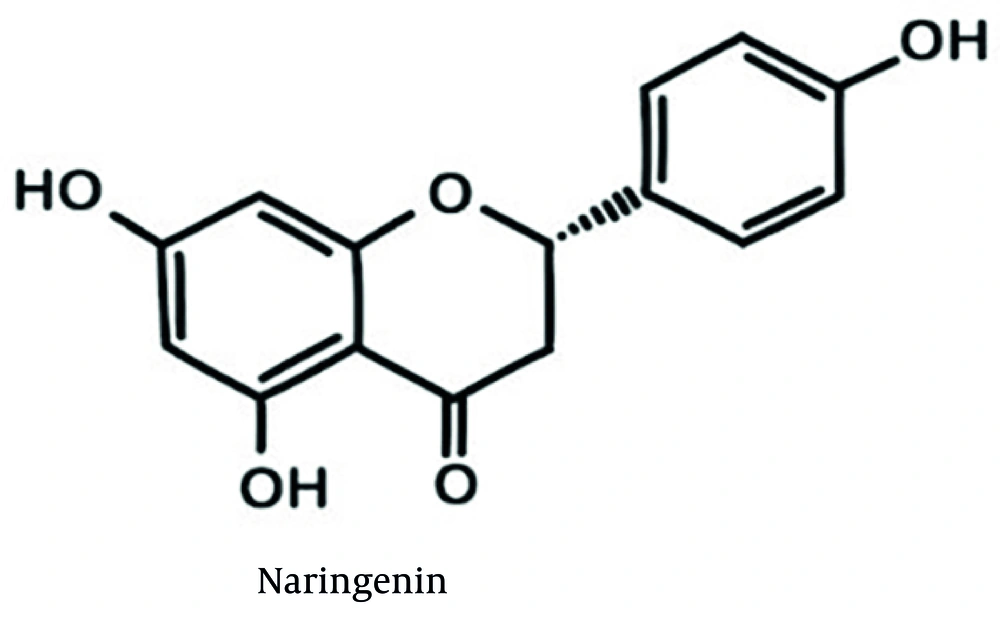

Naringenin is a phytochemical flavonoid. It is widely found in citrus fruits and some other fruits such as bergamot, tomatoes, cocoa, and cherries. This substance has interesting medicinal effects such as anti-cancer, antioxidant, and anti-inflammatory effects (6). The chemical structure of naringenin is shown in Figure 1. Naringenin is a solid with a melting point of 251°C, a molecular weight of 272.26 g/mol, a LogP of 2.52, and a solubility of 0.214 mg/mL in water (7). Due to naringenin’s hydrophobicity, poor water solubility, extensive gastrointestinal degradation, first-pass hepatic metabolism, and limited membrane permeability, its biological function is impaired, generally leading to reduced oral bioavailability (8-10).

Liposomes are spherical vesicles with a particle size of 30 nanometers to several micrometers and are composed of one or more lipid bilayers that surround aqueous units, as the polar groups locate towards the internal and external aqueous phases. The use of lecithin and cholesterol is fundamental in designing liposomes with optimal stability, permeability, and therapeutic efficiency (11). Lecithin provides the amphiphilic bilayer structure, while cholesterol enhances its robustness and resistance to environmental and biological challenges. Together, they enable the development of reliable drug delivery systems that improve bioavailability, reduce side effects, and allow targeted and controlled drug release. This synergy is a cornerstone in the advancement of liposome-based therapies (11, 12). Also, liposomes are biocompatible and biodegradable and have low toxicity. They can encapsulate hydrophilic and lipophilic drugs and facilitate targeted drug delivery to tumor tissues (13). These advantages have led to the development of liposomes both as a research system and commercially as a drug delivery system (11-13).

Skin is the main organ of the human body and the unique and final link between the body and the outside environment. Its easy availability and wide area have made it widely considered for drug delivery (14). Skin is used as a route of drug administration mainly for topical drug delivery (where the drug is placed in the skin layers) and transdermal drug delivery (where the drug passes through the skin and reaches the blood circulation). Despite many benefits, dermal drug delivery has limitations, including weak penetration of the drug due to the presence of a skin barrier (stratum corneum), which causes low bioavailability of the drug (15, 16). Nanocarriers can be used to improve the physicochemical properties of drugs and their interaction with physiological systems. These nanocarriers overcome the limitations of the conventional drug delivery system and also increase the skin penetration of drugs (17). Among nanoparticles, liposomes offer several unique advantages for transdermal drug delivery, including enhanced drug solubility and stability, controlled release, improved biocompatibility, targeted delivery, and skin penetration enhancement. These advantages make liposomes a promising platform for the development of new and improved transdermal drug delivery systems (18, 19).

Numerous studies have shown that naringenin can be used for a wide range of diseases due to its broad pharmacological effects both in vitro and in vivo (20-22). However, the use of this natural product in preclinical studies and clinical trials is limited due to its low water solubility and low oral availability. Previous studies have attempted to enhance naringenin solubility using techniques such as elastic liposomes or polymeric nanoparticles (23, 24). However, the current study focuses on optimizing a classic liposomal formulation using a Full Factorial Design to balance encapsulation efficiency with permeation using biocompatible lipids (lecithin/cholesterol) without the use of synthetic surfactants.

2. Objectives

The aim of this study was to prepare and evaluate the permeability of a naringenin liposomal formulation from rat abdominal skin in order to design an effective topical naringenin formulation.

3. Methods

3.1. Chemicals

Naringenin powder (Purity > 95%) was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (Germany). Liposomal carrier components including cholesterol and egg lecithin were prepared from Merck (Germany). All solvents were of analytical grade, and deionized water was used. Cellulose membrane was prepared from Sigma (Italy).

3.2. Animal Model

Adult male Wistar rats weighing 150 - 170 g and aged 10 - 12 weeks were prepared. After euthanizing the rats in compliance with ethical guidelines (ethical code: IR.AJUMS.ABHC.REC.1400.025), the abdominal surface hair was shaved without damaging the skin, and the skin of the abdominal area was removed without injury. Then, the fats on the inner surface of the skin were dissolved by cold acetone. Until the examination, the prepared skins were kept in aluminum foil and in the freezer at a temperature of -20°C to preserve barrier integrity (25).

3.3. Naringenin Assay

A UV spectrophotometer apparatus (Biowave-2, WPA, UK) at 325 nm was used to measure the amount of naringenin [2]. The method was validated for linearity in the concentration range of 5 - 50 μg/mL (R2 > 0.998).

3.4. Formulation of Naringenin Loaded Liposome

In this study, liposomes were prepared by the thin-layer hydration method, and the influence of independent variables on the final properties of liposomal formulations, drug release profile, and skin permeability was investigated. Liposomes were prepared with different ratios of cholesterol, lecithin, and sonication time at two levels (Table 1). Based on preliminary studies and literature (23, 26), the levels were selected as follows: Egg lecithin (at 40 and 50 mg levels), cholesterol (at 5 and 10 mg levels), and 50 mg of naringenin dissolved in a mixture of chloroform and methanol (2: 1).

| Formulation No | Condition | Lecithin (mg) | Cholesterol (mg) | Sonication Time (min) | Naringenin (mg) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LIP-NG-1 | + + + | 50 | 10 | 10 | 50 |

| LIP-NG-2 | - + + | 50 | 10 | 5 | 50 |

| LIP-NG-3 | + - + | 50 | 5 | 10 | 50 |

| LIP-NG-4 | - - + | 50 | 5 | 5 | 50 |

| LIP-NG-5 | + + - | 40 | 10 | 10 | 50 |

| LIP-NG-6 | - + - | 40 | 10 | 5 | 50 |

| LIP-NG-7 | + - - | 40 | 5 | 10 | 50 |

| LIP-NG-8 | - - - | 40 | 5 | 5 | 50 |

The resulting mixture was then concentrated in a rotary evaporator (Heidolph, Germany) at 60 rpm at 43°C, and a lipid film was formed on the balloon wall. Then 5 mL of phosphate buffer with pH 7.4 was added, and the resulting mixture was sonicated in a sonicator bath (Elmasonic, Germany, 60 Hz) with the desired time cycles (5 and 10 minutes).

3.5. Particle Size Determination

The particle size analyzer apparatus (Scatterscope 1, Qudix, South Korea) was used to evaluate the particle size and polydispersity index (PDI) of liposomes. The particle size of liposomes was measured after dilution with distilled water (3 times for each sample).

3.6. Stability Study

To evaluate stability, the liposomes were kept at 30°C and 65% relative humidity for 3 months. Then, changes in particle size and the amount of drug loaded were examined.

3.7. Entrapment Efficiency Percent (%EE) Determination

Entrapment efficiency percent represents the ratio of the amount of drug loaded in the liposomes to the amount of drug used (27). To determine the loading percentage, after sonication, the mixture was centrifuged at 15,000 rpm at 4°C for 30 minutes using ultracentrifugation (VS-35SMTI, Vision, South Korea). The supernatant solution was centrifuged again at 15,000 rpm at 4°C for 15 minutes. The clear solution was passed through a 0.2-micron filter. Using a UV spectrophotometer (Biowave-2, WPA), the absorption of the solution was read at 325 nm. The concentration of this solution was considered as the concentration of unloaded drug. The entrapment efficiency was calculated using the following formula (27):

In this formula, Qu is the amount of unloaded drug and Qt is the amount of drug that was initially added.

3.8. in vitro Drug Release Study

Franz diffusion cells (4.906 cm2 area, Erweka, Germany) were used to evaluate the release of naringenin from liposomal formulations (28, 29). The cellulose membrane (molecular weight 3000-4000 KD) was hydrated in distilled water for 24 hours at 25°C. 35 mL of methanol-phosphate buffer pH 7.4 (2: 1) was considered as the acceptor phase to maintain sink conditions. For each formulation, the prepared liposomes were diluted with 5 ml of distilled water and considered as a donor phase. Naringenin saturated solution was exposed to similar conditions as a control group. Franz diffusion cells were placed on a heater stirrer (M6.2, CAT, Germany) at 37 ± 0.5°C. At regular time intervals (0.5, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, and 24 hours), 2 mL of the receiver phase was taken and 2 mL of fresh solvent was replaced. Then, a UV spectrophotometer was used to determine the concentrations. This step was repeated 3 times for each formulation. To evaluate the mechanism of naringenin release, the release profile was fitted to kinetic models such as zero order, first order, and Higuchi models.

3.9. ex vivo Skin Permeation Study

The skin samples were taken out of the freezer to reach room temperature and cut into small pieces. Skin samples were in contact with the donor and recipient phases for one day at 37°C before the study. These skin samples were placed on the diffusion cells so that their stratum corneum was in contact with the donor phase. Then 35 mL of methanol-phosphate buffer pH 7.4 (2: 1) was placed in the receiver chamber. Each of the naringenin liposomal formulations was diluted with 5 ml of distilled water and placed in the donor chamber. Naringenin saturated solution was used as a control. The diffusion cells were placed on a heater stirrer at 37°C. Samples were taken at regular intervals for 24 hours and analyzed via UV spectrophotometry.

3.10. Permeability Data Analysis

The cumulative amount of naringenin passed through the skin was plotted against time. Naringenin permeability parameters including flux (Jss), permeability coefficient (P), lag time (Tlag), and apparent diffusion coefficient (Dapp) were measured. The permeability coefficient (P) was calculated using the equation Jss = P × C, where C is the drug concentration in the donor phase. Apparent diffusion coefficient (Dapp) was calculated using the below equation, where h is skin thickness:

The ratio of Jss, Dapp, and P parameters for drug-containing liposomes in comparison with drug saturation solution was considered as ERflux, ERD, and ERp, respectively.

3.11. Statistical Analysis

All experiments were repeated 3 times, and the results were expressed as mean ± SD. A one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used for statistical analysis (P < 0.05). Minitab17 software was used to analyze the effect of independent variables on dependent variables using a Full Factorial Design (23).

4. Results

4.1. Particle Size Determination

Liposomal formulations had a particle size in the range of 76.85 to 169 nm (Table 2). LIP-NG-8 exhibited the largest particle size, while LIP-NG-1 had the smallest particle size. The results of regression analysis showed that particle size had no significant correlation with cholesterol amount, lecithin amount, or sonication time (P > 0.05).

| Formulation | Drug loading percent | Particle Size (nm) | Polydispersity Index | Particle Size after 3 Months |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| LIP-NG-1 | 98.4 ± 1.2 | 76.85 ± 3.5 | 0.365 ± 0.05 | 75.59 ± 4.1 |

| LIP-NG-2 | 99.1 ± 0.5 | 151.5 ± 6.06 | 0.368 ± 0.06 | 149.85 ± 5.8 |

| LIP-NG-3 | 99.01 ± 0.2 | 147 ± 1.11 | 0.361 ± 0.04 | 145.2 ± 3.21 |

| LIP-NG-4 | 98.88 ± 1 | 102.2 ± 5.37 | 0.355 ± 0.05 | 101.5 ± 5.41 |

| LIP-NG-5 | 98.2 ± 0.6 | 107.45 ± 6.67 | 0.363 ± 0.05 | 105.63 ± 5.11 |

| LIP-NG-6 | 98.01 ± 0.4 | 133.15 ± 7.87 | 0.358 ± 0.01 | 132.6 ± 2.85 |

| LIP-NG-7 | 98.99 ± 0.2 | 154 ± 5.65 | 0.364 ± 0.03 | 152.1 ± 5.63 |

| LIP-NG-8 | 99.11 ± 0.5 | 169 ± 4.24 | 0.353 ± 0.06 | 167.91 ± 6.98 |

a Values are expressed as mean ± SD.

4.2. Entrapment Efficiency Percent Determination

The drug loading percentage in liposomal formulations was in the range of 98.01 to 99.11% (Table 2). Therefore, a very small amount of drug is wasted during the production process. The high loading of naringenin can be due to the hydrophobic nature of naringenin, which leads to the placement of this substance in bilayers of liposomes (18). No significant correlation was observed between loading and the tested variables (P > 0.05).

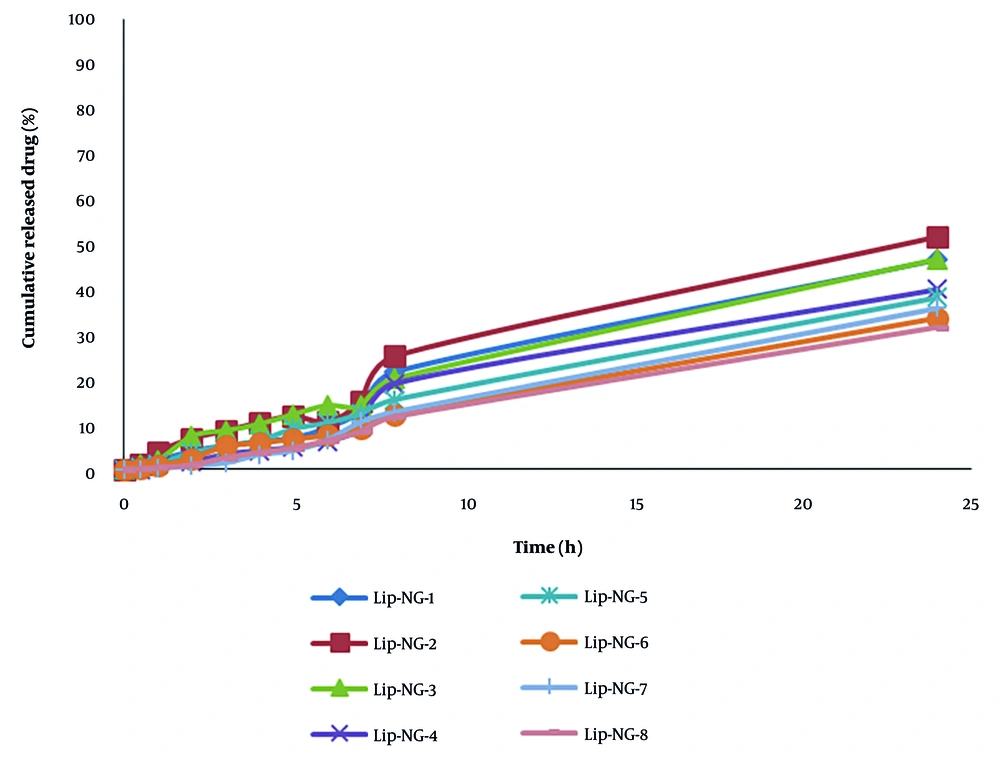

4.3.Drug Release Profile

Drug release from liposomal formulations was evaluated within 24 hours. In this study, the highest rate of release after 4 and 24 hours was related to LIP-NG-2 (Table 3). Regression analysis showed that the amount of naringenin released after 4 hours has a significant correlation with the amount of lecithin (P < 0.05). In all formulations studied, the kinetics of naringenin release follow the first-order model (Figure 2).

| Formulation | Release % (4 h) | Release % (24 h) | Higuchi (r2) | First-Order (r2) | Zero-Order (r2) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LIP-NG-1 | 6.17 ± 0.14 | 46.54 ± 0.26 | 0.906 | 0.975 | 0.968 |

| LIP-NG-2 | 10.38 ± 0.07 | 51.64 ± 0.05 | 0.920 | 0.975 | 0.966 |

| LIP-NG-3 | 10.04 ± 0.14 | 46.69 ± 1.93 | 0.958 | 0.992 | 0.984 |

| LIP-NG-4 | 4.14 ± 0.07 | 39.92 ± 0.93 | 0.883 | 0.961 | 0.953 |

| LIP-NG-5 | 6.4 ± 0.5 | 38.11 ± 0.15 | 0.959 | 0.998 | 0.992 |

| LIP-NG-6 | 5.83 ± 0.21 | 33.59 ± 0.21 | 0.935 | 0.995 | 0.995 |

| LIP-NG-7 | 3.27 ± 0.1 | 35.76 ± 0.43 | 0.908 | 0.986 | 0.985 |

| LIP-NG-8 | 3.77 ± 0.04 | 31.55 ± 0.31 | 0.921 | 0.992 | 0.992 |

a Values are expressed as mean ± SD.

4.4. ex vivo Skin Permeation

The results of the permeability parameters are given in Tables 4 and 5. The values for Dapp and P were recalculated to correct for unit conversion. LIP-NG-8 had the highest Dapp and LIP-NG-6 had the lowest Dapp. LIP-NG-3 had the highest P. Regression analysis showed that Jss had a significant correlation with cholesterol and lecithin amount (P < 0.05). Tlag had a significant correlation with cholesterol amount (P < 0.05).

| Formulation | Jss (mg/cm2.h) | Tlag (h) | Dapp (cm2/h × 10-4) | P (cm/h × 10-4) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control | 0.0002 ± 0.00001 | 8.5 ± 0.7 | 0.159 ± 0.01 | 0.20 ± 0.01 |

| LIP-NG-1 | 0.0243 ± 0.004 | 1.97 ± 0.5 | 0.71 ± 0.02 | 24.5 ± 4.0 |

| LIP-NG-2 | 0.0004 ± 0.00001 | 1.4 ± 0.14 | 0.97 ± 0.09 | 45.0 ± 1.0 |

| LIP-NG-3 | 0.0042 ± 0.0005 | 3.96 ± 0.62 | 0.34 ± 0.05 | 17.0 ± 1.0 |

| LIP-NG-4 | 0.00035 ± 0.0002 | 0.2 ± 0.01 | 2.30 ± 0.80 | 35.0 ± 4.0 |

| LIP-NG-5 | 0.00035 ± 0.00001 | 0.63 ± 0.02 | 0.03 ± 0.01 | 0.30 ± 0.01 |

| LIP-NG-6 | 0.0034 ± 0.0001 | 4.48 ± 0.02 | 0.30 ± 0.01 | 3.50 ± 0.10 |

| LIP-NG-7 | 0.00055 ± 0.00001 | 1.46 ± 0.12 | 0.29 ± 0.01 | 0.50 ± 0.10 |

| LIP-NG-8 | 0.0039 ± 0.0002 | 0.82 ± 0.02 | 18.98 ± 0.05 | 3.90 ± 0.20 |

a Values are expressed as mean ± SD.

| Formulation | ERflux | ERD | ERp |

|---|---|---|---|

| LIP-NG-1 | 121.5 ± 2.23 | 4.53 ± 1.6 | 123.4 ± 4.1 |

| LIP-NG-2 | 2 ± 0.47 | 6.128 ± 1.12 | 2.01 ± 0.0001 |

| LIP-NG-3 | 21 ± 2.82 | 2.18 ± 0.52 | 81.29 ± 1.2 |

| LIP-NG-4 | 1.75 ± 0.25 | 55 ± 1.48 | 1.77 ± 0.48 |

| LIP-NG-5 | 1.75 ± 0.35 | 14.78 ± 2.58 | 1.78 ± 0.36 |

| LIP-NG-6 | 17 ± 1.1 | 1.89 ± 0.14 | 17.34 ± 1.2 |

| LIP-NG-7 | 2.75 ± 0.35 | 5.88 ± 1.23 | 2.77 ± 0.45 |

| LIP-NG-8 | 19.5 ± 1.54 | 126.23 ± 3.35 | 19.67 ± 1.6 |

a Values are expressed as mean ± SD.

5. Discussion

Naringenin is one of the most important flavonoids medicinally. Naringenin has therapeutic effects, including anti-cancer properties, insulin-like functions in the treatment of diabetes, antioxidant effects, and anti-inflammatory properties (1-5). Due to its hydrophobic nature, poor water solubility, widespread destruction by the digestive system, the presence of first-pass liver metabolism, and low membrane permeability, the biological function of naringenin is impaired (8-10).

Transdermal drug delivery is an alternative route for drug administration. This administration route avoids first-pass hepatic metabolism and is non-invasive (21). However, the stratum corneum limits drug penetration (22, 30). Nanoparticles, including liposomes, overcome these limitations (17). Due to their high membrane fluidity, liposomes are promising carriers for improving the skin penetration of drugs (23). Liposomes enhance drug permeation by increasing skin diffusion and distribution, acting as permeation enhancers due to the similarity of their lipids to stratum corneum lipids (20, 30).

The present study evaluated eight liposome formulations. The results showed that liposomes could act as permeation enhancers. Our findings are consistent with Tsai et al. (23), who reported enhanced permeation of naringenin using elastic liposomes. However, our formulation achieves significant flux enhancement (ERflux > 100 for LIP-NG-1) using only lecithin and cholesterol, suggesting that complex surfactants may not always be necessary for effective delivery. Additionally, Joshi et al. (24) found that polymeric nanoparticles increased naringenin accumulation in the skin. Similarly, our liposomal data (high Dapp for LIP-NG-8) suggests that liposomes can facilitate the depot formation of the drug in the skin layers.

Comparing the current work with previous studies on naringenin-loaded microemulsions and polymer-based carriers, our liposomal system offers a distinct advantage in terms of biocompatibility by avoiding synthetic surfactants often used in microemulsions. The high entrapment efficiency (> 98%) observed in our study is comparable to or higher than those reported for other nanocarriers, confirming the suitability of liposomes for hydrophobic drugs like naringenin (26).

5.1. Conclusion

The results of the present study showed that liposomes can be used as absorption enhancers to increase the skin passage of water-insoluble compounds like naringenin. LIP-NG-8 was identified as a promising formulation with high diffusivity. This study showed that formulating naringenin as a topical liposome could address limitations like poor solubility and low oral bioavailability. However, this study had limitations, including the use of ex vivo models and a hydro-alcoholic receptor phase, which may overestimate flux compared to physiological conditions. Future works should focus on long-term stability (> 6 months), morphological characterization (TEM), and in vivo anti-inflammatory efficacy in animal models.