1. Background

This is a growing public health concern about the rising usage of waterways, especially for the disposal of human waste and the consequences of additional organic matter and pathogens (1-4). Several studies conducted in Nigeria, including those focused on the Lagos Lagoon and other coastal ecosystems, have documented high levels of microbial and chemical contamination resulting from urban effluents, domestic sewage, and industrial discharges (5, 6). These findings point out the vulnerability of Nigeria’s marine and estuarine environments, particularly in Lagos, where rapid urbanization, inadequate waste management facilities, and poor environmental regulations have worsened pollution levels (7). Research from Nigeria and other developing economies has further shown that careless waste disposal and untreated effluent discharge result in serious health consequences and deterioration of aquatic environments (8-10). In Lagos, these practices have contributed to high microbial populations and the presence of multidrug-resistant (MDR) bacteria in aquatic ecosystems (11, 12).

Pharmaceutical and industrial effluents constitute the major sources of this contamination. The waste products generated by pharmaceutical companies during the manufacturing of medications are known as pharmaceutical discharges (13). Antibiotic prescriptions and over-the-counter drugs are among the substances found in the effluents of the pharmaceutical business (14). These activities often contain residual antibiotics, active pharmaceutical ingredients, and metabolites which enter the environment via improper waste disposal (1, 12). The disposal of antibiotics into aquatic environments has garnered attention as a significant environmental issue due to the potential risks it poses to human health and the ecosystem (15). Due to insufficient waste management systems, leaching, runoff from land treated with human or agricultural waste, and warfare, the majority of antibiotics used to treat people, cattle, animals, and plants are discharged into the environment in their unaltered precursor form (5, 15, 16). Studies from Lagos and other southwestern regions of Nigeria have reported the presence of ciprofloxacin, amoxicillin, tetracycline (TET), and other antibiotics in surface and groundwater sources (6, 12, 17). This indicates extensive pollution from pharmaceutical, hospital, and municipal wastewater. The continuous release of these substances into aquatic systems creates selective pressures that drive the evolution and spread of antibiotic-resistant microorganisms. Suzuki et al. (18) found a correlation between the disposal of numerous medications and antimicrobial resistance (AMR) in aquatic environments. Antibiotic-resistant microorganisms found in pharmaceutical wastewater can cause infections that are resistant to medications (19). The AMR is a serious global public health issue and is on the rise (7, 20). In Lagos’s marine and coastal ecosystems, high levels of fecal coliforms, Escherichia coli, and Pseudomonas spp. have been isolated, indicating fecal contamination and the presence of MDR strains (6, 12). Similarly, Ajayi and Akonai (5) reported multiple antibiotic resistances in bacterial isolates from Lagos Lagoon.

Despite the growing evidence of antibiotic pollution and resistance in Nigeria’s aquatic environments, studies focusing on marine bacterial isolates from Lagos coastal waters remain limited compared to those found in clinical settings (18, 21, 22). Addressing this threat requires a holistic approach, including control measures, the creation of novel antibiotics, and a thorough understanding of antibiotic sensitivity profiles in clinical and environmental settings due to their implications for both ecological and human health (21). Marine bacteria exhibit diverse antibiotic resistance patterns influenced by natural factors and human activities. The AMR in marine bacteria can arise from natural selection due to environmental stressors like exposure to antibiotics produced by marine microorganisms or pollutants such as heavy metals (HMs) (23, 24). Human activities significantly contribute to antibiotic resistance in marine ecosystems; pollution from pharmaceutical industries, industrial effluents, and agricultural runoff introduces antibiotics and resistant bacteria, exerting selective pressures that favor resistant strains (21, 25). Moreover, the indiscriminate use of antibiotics in medicine and animal husbandry, sewage disposal, and runoff into natural environments can directly influence marine bacteria communities, promoting the survival and spread of resistant strains (21). Recent findings highlight the dynamic nature of antibiotic resistance in marine bacteria, stressing the urgency of intense monitoring and management strategies. Surveillance programs that assess the antibiotic sensitivity profiles of marine bacteria are imperative for understanding the prevalence and spread of resistant bacteria. Such data can inform policies aimed at reducing antibiotic pollution and safeguarding antibiotic efficacy for human and animal use (25).

2. Objectives

Consequently, the present study aimed to identify characterize, and evaluate the antibiotic susceptibility profiles of two bacteria that were isolated from marine water obtained from the Atlantic Ocean in Lagos State, Nigeria.

3. Methods

3.1. Study Design

The study involved experimental, lab-based research that examined the morphological features, biochemical profile, and antibiotic sensitivity of the bacterial isolates recovered from the marine environment.

3.2. Study Location and Source of the Two Bacteria

The laboratory work was conducted at the Department of Microbiology, Obafemi Awolowo University, Ile-Ife, Osun State, Nigeria. The two bacteria isolated from marine water samples were obtained from stock cultures maintained on nutrient agar (NA) slants, which were sealed to prevent desiccation, and stored at 4°C in the microbiology laboratory of the department. The marine water samples were obtained from the Atlantic Ocean in Lagos State, Nigeria.

3.3. Preparation of Media

All culture media, including agar and broth formulations, were prepared in accordance with the Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute guidelines (26) and the respective manufacturer’s instructions. The required quantities of each medium were accurately weighed and dissolved in the appropriate volume of distilled water in sterile conical flasks. The media were sterilized by autoclaving at 121°C for 15 minutes at 15 mmHg. After sterilization, agar media were aseptically poured into sterile Petri dishes and allowed to set properly, while broth media were dispensed into sterile McCartney bottles. All media were stored under appropriate conditions until use.

3.4. Standardization of Inoculums

The inoculum was standardized primarily for the antibiotic susceptibility testing to ensure consistent bacterial density and a reliable result. Therefore, 5 mL of physiological saline was poured into sterile test tubes of identical size, produced separately for each bacterial isolate, and labeled appropriately. Then, using a sterile inoculating loop, a loopful of each of the 24-hour-old cultures was aseptically transferred into its respective test tube to prepare the bacterial suspension. The bacterial suspensions were then adjusted to achieve colony-forming units of 0.5 McFarland standards (106 - 108 cfu/mL cells) using a colorimeter at a specific wavelength of 600 nm.

3.5. Morphological and Biochemical Characterization

The pure colonies of the bacterial isolates were subjected to morphological and biochemical characterization. The preliminary identification involved Gram staining, followed by assessment of colony morphology and a series of conventional biochemical assays. Gram staining was performed following the standard protocol described by Tripathi et al. (27) to differentiate the bacterial isolates based on cell wall structure. The morphological characteristics examined included colony shape, surface texture, margin, color, and elevation. Biochemical characteristics were determined using conventional tests in accordance with the guidelines outlined in Bergey’s manual of determinative bacteriology (28, 29) for accurate identification and characterization of the two bacterial isolates. The biochemical tests performed included spore staining, catalase test, indole test, motility test, hydrogen sulfide production, citrate utilization, methyl red Voges-Proskauer (MR-VP) test, gelatin liquefaction, starch hydrolysis, coagulase test, nitrate reduction, and sugar fermentation.

3.6. Determination of Antimicrobial Resistance

The antibiotic resistance of the bacterial isolates was determined using the Kirby-Bauer disk diffusion method, following the procedures (26). A standardized bacterial suspension equivalent to 0.5 McFarland was prepared and evenly streaked across the surface of freshly prepared Mueller-Hinton agar plates. Antibiotic discs of known concentrations; nitrofurantoin (NIT) (200 µg), nalidixic acid (NAL) (200 µg), ampicillin (AMP) (25 µg), clotrimazole (25 µg), gentamicin (GEN) (10 µg), tetracycline (25 µg), colistin (COL) (25 µg), and streptomycin (STR) (25 µg) were aseptically placed on the inoculated agar surfaces. The plates were then inverted and incubated at 37°C for 18 - 24 hours. After incubation, the zones of inhibition were measured to the nearest millimeter using a transparent ruler.

4. Results

4.1. Cultural and Morphological Characteristics of the Isolates

The morphological and cultural traits of the two bacterial isolates, P. aeruginosa (S1) and E. coli (S2), obtained from a marine water sample are displayed in Table 1. In contrast to S1, distinct greenish-black growths were seen on eosin methylene blue (EMB) agar for S2. Both isolates, S1 and S2, were found to be Gram-negative, which indicates that these bacteria possess a thin layer of cell wall or murein covered by an external cell membrane.

| Characteristics and Tests | Isolates | |

|---|---|---|

| S1 a | S2 b | |

| Cultural agar colonies | ||

| Medium | EMB | EMB |

| Surface | Distinct | Distinct |

| Shape | Circular | Circular and smooth |

| Elevation | Slightly convex | Slightly convex |

| Margin | Entire | Entire |

| Pigment | Colorless | Metallic green sheen |

| Cultural agar colonies | ||

| Medium | NA | NA |

| Surface | Distinct | Smooth, distinct |

| Shape | Circular | Circular |

| Elevation | Slightly convex | Slightly convex |

| Margin | Irregular | Entire |

| Pigment | Green | Grayish white |

| Morphological test | ||

| Cell Shape with Gram staining | Rod (short) | Rod (short) |

| Gram reaction | Negative | Negative |

Abbreviations: EMB, eosin methylene blue agar; NA, nutrient agar.

a Pseudomonas aeruginosa.

b Escherichia coli.

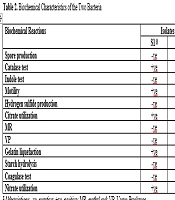

4.2. Biochemical Characterization

The biochemical tests conducted to characterize the two bacteria isolated from a marine water sample revealed distinct profiles for each organism, S1 and S2 identified as P. aeruginosa and E. coli, as illustrated in Tables 2 and 3. Both isolates, S1 and S2, were found to be non-spore-producing, as shown by the red staining of the bacterial cells when observed under an oil immersion objective lens after 72 hours of culture. The isolates were stained with malachite green and counterstained with safranin. The catalase test showed that both isolates were positive, as demonstrated by the release of oxygen gas from the enzymatic breakdown of hydrogen peroxide. In terms of indole production, S1 tested negative, which implied it cannot convert tryptophan to indole, while S2 tested positive, which showed that it possessed the metabolic capability to convert tryptophan to indole, as evidenced by the broth’s surface layer turning reddish-violet in hue. Both isolates were motile when viewed under a 40X objective lens, which is typical for a wide range of bacterial genera and indicated the presence of flagella for movement. S1 and S2 tested negative for hydrogen sulfide production, as indicated by the absence of blackening of the content of the inoculated SIM medium. This suggested that they do not reduce sulfur compounds to hydrogen sulfide.

Abbreviations: -ve, negative; +ve, positive; MR, methyl red; VP, Voges-Proskauer.

a Pseudomonas aeruginosa.

b Escherichia coli.

Abbreviations: NC/AG, no color change, acid and gas production; CAG, color change, acid and gas production; CA/NG, color change, acid production and no gas.

aPseudomonas aeruginosa.

bEscherichia coli.

The successful citrate utilization noted in S1 indicates that the isolate effectively generated the enzyme citrate, allowing it to use citrate as its primary nutrient and energy source. This was evidenced by the change in color of the culture medium from green to blue. In contrast, S2 did not demonstrate this capability, highlighting the variations in their metabolic pathways and abilities. The MR test showed S1 as negative, which implied that the isolate does not produce stable acid end products from glucose fermentation, whereas S2 tested positive, indicated by the development of red coloration, and suggested that the isolate was able to break down glucose to generate an organic acid and gas combination. The negative outcome of the Voges-Proskauer assay for S1 suggests that the isolate does not produce 2,3-butanediol as a final product of glucose fermentation, whereas S2 yielded positive result, demonstrated by the development of red coloration due to the formation of acetoin or 2,3-butanediol.

The gelatin liquefaction results demonstrated that S1 has the ability to hydrolyze gelatin, while S2 lacked this capability. Both isolates were negative for starch hydrolysis, as indicated by the absence of clear zones following addition of Gram iodine solution to the inoculated culture medium, suggesting they do not produce amylase to break down starch into simple sugars. The coagulase test also yielded negative results for both isolates, which indicate that they do not produce coagulase enzymes. Moreover, both S1 and S2 tested positive for nitrate reduction, demonstrated by the color change to red or pink and the availability of gas bubbles trapped at the top of the inverted gas collection tube, indicating that the two organisms can transform nitrate into nitrite or other nitrogenous compounds.

Finally, the reactions produced by the sugar fermentation test performed on the two isolates on a culture medium containing the three different tested sugars (glucose, lactose, and mannitol) (Table 3). The reactions are categorized based on the generation of gas and acid, as well as the existence of color change. Isolate S1 showed no fermentation activity across all three tested sugars, which implied that this isolate does not metabolize these sugars. However, isolate S2 demonstrated fermentation to all the tested sugars. For glucose and lactose, S2 produced both acid and gas, whereas in the case of mannitol, S2 produced acid but no gas. Also, there was a color change from red to yellow in S2, but no color change was observed in S1. This showed that S1 and S2 have distinct metabolic capabilities and pathways. Hence, this metabolic potential of S2 to break down multiple fermentable carbohydrates to produce acid by-products and/or gas formation may have implications for its ecological role and its adaptation to the marine environment.

Table 4 displayed the antibiotic resistance test of the two organisms S1 and S2, against a panel of eight antibiotics as obtained on the Kirby-Bauer disc diffusion method. Both isolates exhibited resistance to multiple antibiotics, notably ampicillin, tetracycline, and nitrofurantoin, but were sensitive to COL. Isolate S1 showed resistance to six antibiotics (NIT, NA, AMP, GEN, TET, STR), with susceptibility observed only for cotrimoxazole (COT) and COL.

Abbreviations: NIT, nitrofurantoin; NAL, nalidixic acid; AMP, ampicillin; COT, cotrimoxazole; GEN, gentamicin; TET, tetracycline; COL, colistin; STR, streptomycin; S, sensitive; I, intermediate; R, resistance.

a Pseudomonas aeruginosa.

b Escherichia coli.

Isolate S2 showed resistance to three antibiotics (NIT, AMP, and TET), susceptibility to NA, GEN, and COL, and an intermediate response to COT and STR. A significant level of MDR was seen among the bacterial isolates, particularly in isolate S1, which showed resistance to most of the antibiotics that were examined.

5. Discussion

The rapid increase in bacterial resistance to antimicrobial therapies is a serious global public health concern, threatening the efficacy of current treatment options and undermining infection control efforts across clinical and environmental settings (20, 30). The marine ecosystem is a storehouse of diverse microorganisms, including pathogenic and non-pathogenic bacteria capable of acquiring and disseminating antibiotic resistance genes (11, 12, 18-21). A holistic approach and comprehensive understanding of the antibiotic sensitivity profile both in clinical and environmental settings are key to addressing this alarming public health challenge. However, AMR in marine ecosystems has not been extensively studied compared to that found in clinical settings (18-21, 31). The findings from this study revealed the two isolates as Pseudomonas aeruginosa (S1) and Escherichia coli (S2). The presence of P. aeruginosa and E. coli from Lagos marine water strongly indicates fecal and industrial contamination, and this finding aligns with previous studies conducted in Lagos Lagoon and other Nigerian coastal ecosystems (4, 5, 32, 33). Both isolates demonstrated distinct physiological and biochemical traits that reflect their adaptive diversity and metabolic specialization in aquatic environments. The biochemical characterization differentiated P. aeruginosa from E. coli based on their substrate utilization patterns and enzyme production profiles. S1 was catalase-positive, citrate-positive, indole-negative, and unable to ferment glucose, lactose, or mannitol. These features align with the well-established descriptions of P. aeruginosa as non-fermentative, oxidase-positive organisms with broad metabolic flexibility and environmental resilience (34). In contrast, E. coli (S2) showed classical Enterobacteriales characteristics, including indole production, MR positive, and the ability to ferment multiple sugars with acid and gas production. These results supported the writings of a number of authors, including Bopp et al. (35), Madigan et al. (36), and Leimbach et al. (37). The metabolic differences between the isolates indicate ecological adaptation and niche specialization. Pseudomonas aeruginosa, being a non-fermentative bacterium, primarily derives energy through oxidative metabolism, which enables its efficient survival in oxygen-rich marine environments. In contrast, E. coli depends largely on fermentative pathways, which suggest possible fecal contamination of the marine ecosystem (33). Therefore, the recovery of E. coli from Lagos marine water indicates human-induced pollution, and this finding is consistent with previous studies that reported high levels of fecal coliforms and enteric bacteria in different sites on coastal water in Lagos (6, 7, 38). Both P. aeruginosa and E. coli are well known opportunistic pathogens with substantial clinical importance. Pseudomonas aeruginosa, are associated with burn wound infections, respiratory diseases, otitis externa, and bacteremia (39-41). Escherichia coli encompasses several pathogenic pathotypes enteropathogenic, enterotoxigenic, enteroinvasive, and enterohemorrhagic which are responsible for gastrointestinal infections ranging from mild diarrhea to hemorrhagic colitis (35, 42-44).

The antibiotic susceptibility testing revealed MDR in both isolates, particularly to nitrofurantoin, ampicillin, and tetracycline. Pseudomonas aeruginosa exhibited additional resistance to NA, GEN, and STR, whereas E. coli was sensitive to NA and GEN but showed intermediate resistance to cotrimazole and STR. These variations underscore species-specific differences in antibiotic resistance mechanisms, possibly due to genetic factors and environmental exposure (45, 46). These findings are consistent with previous reports from Lagos and other aquatic environments in Nigeria that documented MDR P. aeruginosa and E. coli strains (33, 47-49). Moreover, the observed resistance to tetracycline and β-lactams (AMP) corroborates earlier findings from aquatic systems in Lagos and other parts of Nigeria, where P. aeruginosa and E. coli isolates harbored transferable tetracycline resistance genes (tetA, tetB, tetM) and β-lactamase genes (5, 33, 49, 50). These genes are often found on plasmid, and can be transferred among marine and enteric bacteria (48). The co-resistance to aminoglycosides (GEN, STR) observed in P. aeruginosa further supports the possibility of mobile genetic element-mediated dissemination of MDR factors, a phenomenon well-documented in studies of aquatic ecosystems by Meradji et al. (50) and Pazra et al. (51). Furthermore, both isolates remained susceptible to COL, although this finding may suggest it continued efficacy against these marine isolates, but it has to be interpreted with caution due the increasing detection of plasmid-mediated COL resistance in African isolates (52-54) and lack of further confirmation test in this study. Therefore, this observation warrants further research to validate its exact efficacy and to evaluate its broader clinical implications. Globally, MDR in marine-derived P. aeruginosa and E. coli has been increasingly reported. Studies from Tunisia (50), India (55), Poland (46), and Brazil (56) describe similar resistance patterns particularly to tetracycline, β-lactams, and sulfonamides which suggesting that the isolates from marine water in Lagos are part of a global environmental trend of antibiotic resistance in coastal waters. The persistence of tetracycline resistance in marine environments may be attributed to the extensive use of this antibiotic in aquaculture and livestock, with subsequent runoff into the marine system (46, 51-56). The detection of MDR bacteria in Lagos marine waters has substantial ecological and public-health implications. Coastal waters near urban centers such as Lagos often receive untreated or poorly treated effluents from hospitals, industries, and households, contributing to a complex mixture of antibiotics, resistant bacteria, and resistance genes (38, 56). These conditions create a conducive environment for the selection and transfer resistance genes, not only among environmental bacteria but also to potential human pathogens (57, 58). The co-occurrence of P. aeruginosa and E. coli in the same environment further increases the risk of gene exchange via plasmids and integrons, as both genera are known to participate in interspecies transfer of mobile genetic elements (33, 50). This raises concerns about recreational and occupational exposure of local populations, particularly fishermen and coastal residents, who are in frequent contact with such waters (59, 60).

Beyond antibiotic exposure, the presence of HMs in the Lagos marine environment may have contributed to the emergence and maintenance of AMR. Studies by Adeyemi et al. (61), and Ita and Anwana (62) have reported elevated levels of metals such as cadmium (Cd), lead (Pb), mercury (Hg), and zinc (Zn) in the Lagos coastal zone. The HMs exert co-selective pressure on bacterial populations by favoring strains that carry both metal-resistance genes (MRGs) and ARGs on the same genetic elements, such as plasmids and transposons (23). Recent researches have shown that environmental contaminants like HMs and microplastics act not merely as passive pollutants but as active drivers of AMR evolution (50, 63-65). Historical genomic analyses have revealed that MRGs existed long before the clinical antibiotic era, and therefore suggest that ancient metal resistance mechanisms may have laid the genetic foundation for contemporary antibiotic resistance (65-67). Consequently, the interplay between antibiotic residues, HMs, and microbial communities in Lagos marine waters likely accelerates the co-selection and persistence of MDR phenotypes in environmental bacteria.

5.1. Conclusions

The presence of MDR P. aeruginosa and E. coli in the studied marine environment highlights its potential role as a reservoir of AMR genes. These findings stress the urgent need for continuous monitoring of coastal ecosystems and the implementation of local antimicrobial stewardship strategies to mitigate the environmental dissemination of resistance determinants resulting from indiscriminate antibiotic use and other human activities. Additionally, more study is required to investigate the genetic basis of resistance and create plans for efficient antibiotic stewardship in clinical and environmental settings.

5.2. Limitations

There are certain restrictions on this study, though. First, the study was limited to only two bacterial isolates and as such does not reflect the true bacterial diversity of the marine ecosystem where the sample was collected. In addition, molecular characterization of antibiotic resistance genes in these two bacterial species was not performed due to financial constraint. Finally, it is imperative to acknowledge that the study’s capacity to illustrate the varying trends of bacterial resistance over an extended period of time may be restricted. This is because the susceptibility of bacteria to antibiotics could change due to the introduction of new strains and modifications in the utilization of medications. As such, there may be limitations to the study’s application to treatment approaches in the future.

5.3. Public Health Significance

The global increase in antibiotic resistance is a serious threat since it reduces the ability of frequently administered antibiotics to treat common bacterial infections (18-21, 68). There are concerning patterns of resistance among important bacterial diseases, according to the 2022 global antimicrobial resistance and use surveillance system (GLASS) report. Due to its cross-border spread, AMR is a serious worldwide issue that affects nations of all economic levels. This crisis is fueled by a number of factors, including limited access to clean water, sanitation, and hygiene (WASH) for humans and animals; ineffective infection and disease prevention strategies in homes, hospitals, and agricultural settings; a lack of affordable vaccines, diagnostics, and treatments; a lack of knowledge and comprehension; and a lack of enforcement of pertinent laws (68, 69). The origins and effects of AMR disproportionately affect populations in low-resource environments, making them more vulnerable (68). Also, globally, public health systems and clinical facilities reflected the "COVID effect" on AMR (70). Hospital-onset infections, which are often linked to AMR, were shown to be more common in patients with and without COVID-19 (70). Increased equipment and invasive operations, a more critically ill patient case mix, intensive care unit (ICU) admission, immunological suppression and other predisposing conditions, and longer hospital stays that raise the risk of infection are some of the hypothesized reasons (71, 72). Overcrowding, widespread antibiotic usage, and failures in infection control and antibiotic stewardship efforts due to time and resource constraints may have contributed to the onset and spread of AMR in hospital settings and communities during COVID-19 era (70, 73). The AMR is a complicated issue that calls for targeted responses from a variety of industries, such as food production, animal health, human health, and environmental protection, in addition to a cooperative, cross-sectoral approach (68). This study highlights that addressing AMR in human health necessitates prioritizing infection prevention to minimize unnecessary antimicrobial usage, guaranteeing fair access to high-quality diagnostics and treatments, and promoting innovation through focused initiatives such as AMR monitoring, tracking antimicrobial usage, and developing new vaccines, diagnostics, and treatment options.