1. Background

Polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) is one of the most prevalent endocrine disorders among women of reproductive age (1, 2). There is controversy regarding the prevalence of the condition among different studies; for example, Spritzer et al. documented the range of prevalence as 8% to 13% (3), while Tehrani et al. wrote about a prevalence rate of 7.1% to 14.6% in Iran (4). The incidence of PCOS is increasing at the global level, especially with the increasing prevalence of type 2 diabetes (2, 5).

Polycystic ovary syndrome is a complex clinical syndrome that is mainly characterized by hyperandrogenism, anovulation, and infertility (6). Although it is best known as a reproductive illness, it is also linked with various metabolic disturbances (such as insulin resistance, impaired glucose tolerance (IGT), type 2 diabetes, obesity, dyslipidemia, hypertension, and cardiovascular disease), reproductive disorders (such as hyperandrogenism, irregular menses, infertility, and pregnancy complications), and mental illnesses (particularly decreased quality of life, anxiety, and depression) (7).

The etiology of PCOS is not yet understood, but it is believed to be a multifactorial, polygenic disorder with both genetic and environmental origins (8). One of the most significant features in the pathogenesis of PCOS is insulin resistance. Insulin resistance causes an elevated production of androgens by the ovaries and adrenal glands and diminished hepatic secretion of sex hormone-binding globulins (SHBG), ultimately causing elevated free circulating androgens and the development of clinical features (9). Insulin resistance occurs in 50% to 75% of women with PCOS, advancing to 95% in obese women (10). While the underlying mechanisms of insulin resistance in PCOS remain to be demonstrated, earlier investigations have suggested a role for testosterone and androgen receptors (11).

There has been evidence of a defective phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K) pathway — the main pathway through which insulin produces its metabolic actions, such as glucose uptake in skeletal muscles — in PCOS patients (12). The defect can account for the disorder's hallmark metabolic disturbances. Additionally, as a compensatory mechanism for insulin resistance, hyperinsulinemia ensues, but the mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) pathway in these women is normal (13). Activation of this pathway causes elevated steroidogenesis and is one of the causes of hyperandrogenism (14). Insulin resistance, thus, has a pivotal role in both the metabolic and hyperandrogenic phenotype of PCOS. Enhancement of insulin sensitivity — by therapeutic lifestyle modification or medication — can drastically improve symptoms and reproductive function (15).

Various cross-sectional and prospective studies have presented an increased prevalence of type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) and IGT among PCOS patients (16). The risk of having IGT among women with PCOS is three to seven times greater than in the control populations, as reported by Trakakis et al. (17). It has also been documented that the age at which IGT develops in PCOS patients is younger, and the rate of progression from IGT to type 2 diabetes is greater in such patients compared to those without PCOS (18).

The incidence of IGT among PCOS patients differs between races. For instance, it has been demonstrated in American women with PCOS that the incidence of IGT (35%) and T2DM (7% - 10%), whereas in European women with PCOS the incidence of IGT = 12%, T2DM = 1.7% (17, 19). A systematic review that took into account the ethnicity of participants concluded that the prevalence of IGT in Asian women with PCOS was 2.5 times higher than controls, 4.4 times higher in American women, and 6.2 times higher in European women (20).

Although a high percentage of PCOS patients are insulin resistant and have IGT, the reported prevalence is inconsistent owing to variability in study populations and ethnic groups. In addition, most of the previous research has been performed on European subjects, and evidence regarding non-European IGT prevalence is limited, especially coming from developing nations. Given some major ethnic and geographic differences in IGT prevalence, the current study tried to evaluate PCOS patients who visited the infertility clinic in Ali Ibn Abi Talib Hospital of Zahedan, Iran between 2020 and 2021 for IGT prevalence.

2. Methods

2.1. Study Population

This case-control study was conducted on women aged 18 - 40 years who were referred to the infertility department of Ali Ibn Abi Talib Hospital in Zahedan between January 21, 2020, and September 22, 2021. The case group included patients diagnosed with PCOS, while the control group consisted of women who visited the same center during the same period for reasons unrelated to PCOS.

Inclusion criteria for the case group were women aged 18 - 40 years with a definitive diagnosis of PCOS based on the Rotterdam criteria, which requires at least two of the following: (1) Oligo/amenorrhea and/or anovulation; (2) clinical and/or biochemical signs of hyperandrogenism; and (3) ultrasound evidence of polycystic ovaries. The inclusion criterion for the control group was women aged 18 - 40 years without clinical, biochemical, or ultrasonographic evidence of PCOS.

Exclusion criteria included endocrine disorders such as hypothyroidism and hyperprolactinemia, use of certain medications within three months prior to the study (including oral contraceptives, anti-androgens, GnRH agonists or antagonists, insulin-sensitizing drugs, and antidepressants), and a history of neoplasms.

2.2. Sample Size Justification

The minimum required sample size was calculated based on previously reported differences in the prevalence of IGT between women with PCOS and controls. Assuming a prevalence of IGT of approximately 30% in the PCOS group and 15% in the control group, with a power of 80% and a significance level of 0.05, the minimum required sample size was estimated to be 52 participants per group (16). Due to the higher number of PCOS referrals to the infertility clinic during the study period, 225 eligible women with PCOS were enrolled. However, owing to financial constraints related to oral glucose tolerance testing, the number of control participants was limited to 55. Despite this imbalance, the control sample size exceeded the calculated minimum requirement.

2.3. Data Collection Tools and Methods

Following the approval of the research proposal and obtaining the necessary permits, arrangements were made with the infertility department of Ali Ibn Abi Talib Hospital to request fasting blood sugar (FBS) and oral glucose tolerance test (OGTT) for all patients referred after the project’s approval date, to ensure data standardization.

Fasting glucose levels were measured using early morning blood samples after 8 to 10 hours of overnight fasting. A fasting glucose level below 100 mg/dL was considered normal. In the OGTT, after a minimum of 10 hours of fasting, patients were given 75 grams of oral glucose, and their serum glucose was measured two hours later. A two-hour serum glucose level below 140 mg/dL was considered normal.

Eligible patient records within the study period were selected using a convenience sampling method. Based on the Rotterdam criteria, patients diagnosed with PCOS were included in the case group, and those without any PCOS symptoms or diagnosis were selected as the control group. Relevant data were extracted from medical files and recorded in data collection forms.

2.4. Study Implementation and Group Allocation

The diagnosis of PCOS was made by experienced gynecologists and endocrinologists at Ali Ibn Abi Talib Hospital according to the Rotterdam criteria. Diagnosis was based on clinical evaluation, hormonal assessment, and pelvic ultrasonography, and was documented in the patients’ medical records. Group allocation was performed retrospectively using medical files. Women with a confirmed diagnosis of PCOS were assigned to the case group, while women without any documented features or diagnosis of PCOS were assigned to the control group. Self-reported diagnosis was not used for group classification.

The study was approved in 2020 by the Ethics Committee of Zahedan University of Medical Sciences under the code IR.ZAUMS.REC.1399.494. Following final approval and acquisition of the required permissions, patient information was collected from medical records. A total of 225 files were selected for the case group and 55 for the control group using convenience sampling. The collected data were recorded in structured information forms and analyzed using SPSS software. Patient confidentiality was maintained throughout all stages of the study.

2.5. Data Analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS version 26. Descriptive statistics such as mean, standard deviation, frequency percentages, and graphs were used to describe the data. For comparing the two groups, independent t-tests and the non-parametric Mann–Whitney U test were applied, as appropriate. A P-value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

3. Results

A total of 280 women were enrolled in the study, comprising 225 women with PCOS and 55 healthy controls. The mean age of participants was 28.86 ± 4.37 years, with no statistically significant difference between the PCOS group (28.75 ± 4.31 years) and the control group (29.34 ± 4.61 years; P = 0.367). Similarly, there was no significant difference in Body Mass Index (BMI) between the PCOS group (27.20 ± 4.46 kg/m²) and the control group (28.03 ± 3.95 kg/m²; P = 0.364; Table 1).

| Variables/Groups | No. | Mean ± SD | Median (IQR) | P-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (y) | 0.367 | |||

| PCOS | 225 | 28.75 ± 4.31 | 28 (6) | |

| Control | 55 | 29.34 ± 4.61 | 29 (7) | |

| Total | 280 | 28.86 ± 4.37 | 29 (5) | |

| BMI | 0.364 | |||

| PCOS | 225 | 27.20 ± 4.46 | 27 (5) | |

| Control | 55 | 28.03 ± 3.95 | 28 (6) | |

| Total | 280 | 27.56 ± 4.31 | 27 (5) | |

| Fasting glucose (mg/dL) | 0.118 | |||

| PCOS | 225 | 95.58 ± 10.75 | 92 (14) | |

| Control | 55 | 93.07 ± 12.49 | 90 (18) | |

| Total | 280 | 95.08 ± 11.14 | 92 (15) | |

| 2-hour postprandial glucose (mg/dL) | 0.038 | |||

| PCOS | 225 | 130.00 ± 25.57 | 125 (29) | |

| Control | 55 | 122.30 ± 23.73 | 120 (32) | |

| Total | 280 | 128.49 ± 25.36 | 124 (32) |

Abbreviations: PCOS, polycystic ovary syndrome; BMI, Body Mass Index.

Fasting blood glucose (FBG) levels did not significantly differ between groups, with mean values of 95.58 ± 10.75 mg/dL in the PCOS group and 93.07 ± 12.49 mg/dL in the control group (P = 0.118). However, the mean 2-hour postprandial glucose level was significantly higher in the PCOS group (130.00 ± 25.57 mg/dL) compared to the control group (122.30 ± 23.73 mg/dL; P = 0.038), suggesting a higher degree of IGT among PCOS patients.

As shown in Table 2, 27.55% of women in the PCOS group had fasting glucose ≥ 100 mg/dL, compared to 25.45% in the control group; this difference was not statistically significant (P = 0.753).

| Groups | Fasting Glucose < 100 mg/dL | Fasting Glucose ≥ 100 mg/dL | P-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| PCOS | 163 (72.45) | 62 (27.55) | 0.753 |

| Control | 41 (74.54) | 14 (25.45) |

Abbreviation: PCOS, polycystic ovary syndrome.

a Values are expressed as No. (%).

With respect to IGT (2-hour glucose 140 - 199 mg/dL), 32.89% of women with PCOS were classified as having impaired tolerance compared to 23.64% in the control group (P = 0.184). Additionally, 21.42% of women in the PCOS group had impaired fasting glucose (IFG, 100 - 125 mg/dL) compared to 6.09% of controls, although this difference also did not reach statistical significance (P = 0.528; Table 3). The results indicate that although the prevalence of IGT did not differ significantly between women with PCOS and controls, mean 2-hour post-load glucose levels were significantly higher in the PCOS group, independent of age and BMI.

| Groups | No | Yes | P-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| IGT (2-h glucose 140 - 199 mg/dL) | 0.184 | ||

| PCOS | 151 (67.11) | 74 (32.89) | |

| Control | 42 (76.36) | 13 (23.64) | |

| IFG (100 - 125 mg/dL) | 0.528 | ||

| PCOS | 165 (58.92) | 60 (21.42) | |

| Control | 38 (13.57) | 17 (6.09) |

Abbreviation: PCOS, polycystic ovary syndrome; IGT, impaired glucose tolerance; IFG, impaired fasting glucose.

a Values are expressed as No. (%).

Correlation analyses are presented in Table 4. The findings revealed a significant positive association between fasting glucose levels and 2-hour postprandial glucose levels (R = 0.543, P < 0.001). Moreover, a weaker but statistically significant correlation was observed between BMI and 2-hour glucose levels (R = 0.176, P = 0.003).

| Variables | Correlation Coefficient (R) | P-Value |

|---|---|---|

| Fasting glucose and 2-hour glucose | 0.543 | < 0.001 |

| BMI and 2-hour glucose | 0.176 | 0.003 |

Abbreviation: BMI, Body Mass Index.

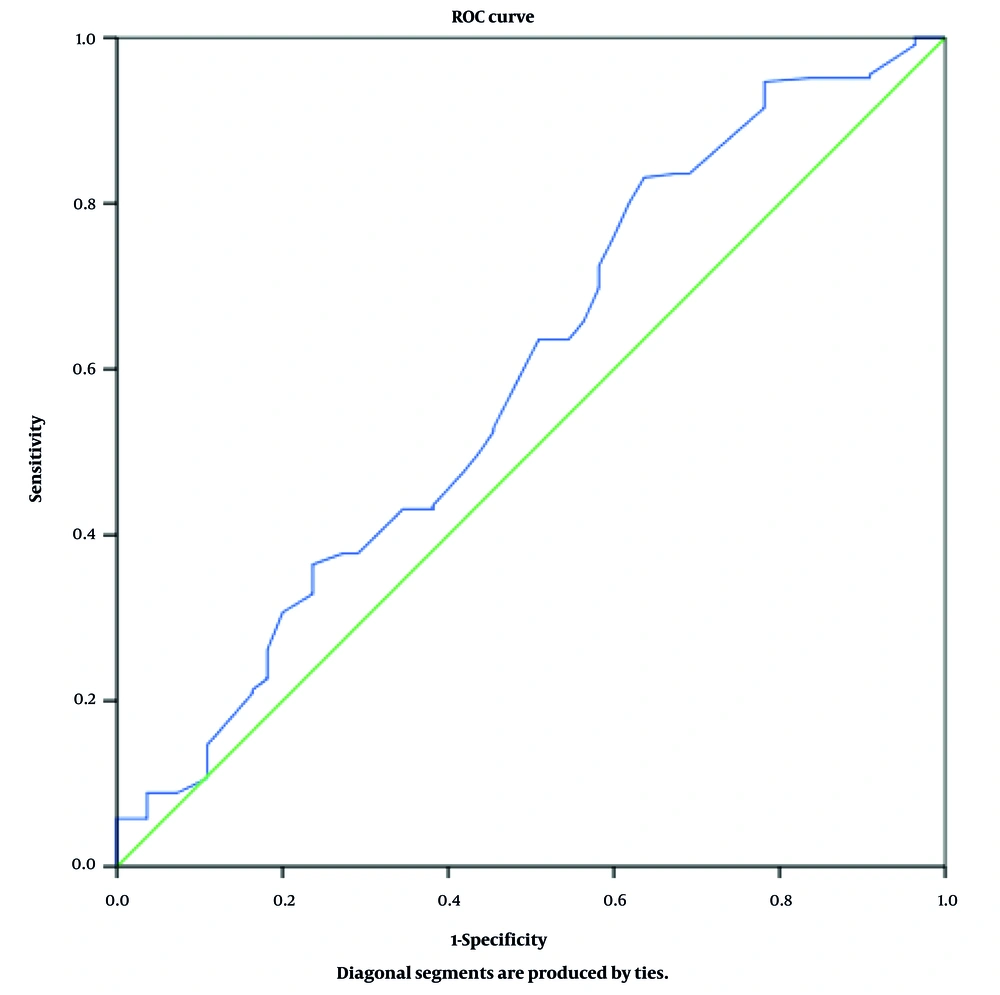

3.1. Diagnostic Value of 2-Hour Glucose Level Based on Receiver Operating Characteristic Curve Analysis

Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC) curve analysis was performed to evaluate the diagnostic performance of the 2-hour postprandial glucose level in detecting glucose metabolism abnormalities in women with PCOS. The ROC curve is a graphical tool used to illustrate the diagnostic ability of a test, based on its sensitivity and specificity at various thresholds.

In this study, the area under the ROC curve (AUC) was 0.589 (95% CI: 0.501 - 0.677; P = 0.041), indicating a modest yet statistically significant discriminatory power. As an AUC greater than 0.5 is generally considered acceptable, these findings suggest that the 2-hour glucose level may serve as a useful screening marker for identifying metabolic disturbances in women with PCOS (Figure 1).

4. Discussion

This case-control study evaluated the prevalence of IGT in women with PCOS compared to women without PCOS at an infertility clinic. The results showed that the prevalence of IGT was 32.89% in PCOS and 23.64% in the control group. The mean postprandial blood glucose at two hours was significantly higher in the PCOS group. The key findings of this study demonstrate that, while the prevalence of IGT was not significantly different between women with PCOS and controls, women with PCOS had significantly higher mean 2-hour post-load glucose levels, suggesting a tendency toward altered glucose metabolism.

Some studies have demonstrated that the prevalence of prediabetes and type 2 diabetes is higher in women with PCOS compared to healthy controls. Metabolic screening in such patients has therefore been seen as vital in a bid to prevent the complications of the disease in the long run (21). Yet, an accurate measure of the incidence of IGT in different ethnic and geographical populations still requires more data.

In a prospective cohort study by Celik et al. in 252 women with PCOS and 117 controls, the rate of IGT was 14.3% and 10.3%, respectively, with a substantial difference between the two groups (22). Likewise, in a study by Wei et al., IGT and diabetes prevalence was 7.6% and 3.1%, respectively, in PCOS patients and 2.9% and 0.2%, respectively, in controls. The authors found that two-hour glucose and fasting and insulin levels were significantly elevated in PCOS patients, reflecting increased susceptibility to IGT (23). These results are consistent with the current study.

Ganie et al. found, in a large population study, that out of 1,746 women with the diagnosis of PCOS, about 36% of them had some type of glucose metabolism disorder. The frequency of such abnormalities was 6% for T2DM, 9.5% for IGT, 14.5% for IFG, and 6.9% for combined IGT-IFG (1). These findings are indicative of the general high frequency of metabolic abnormalities in patients with PCOS and are in agreement with the outcomes of the present study as well.

Molecular and cellular studies have explored the mechanisms of insulin resistance in PCOS women through several different studies. The primary reason for such resistance, according to Barber et al.'s research, is a PI3K pathway defect, which mediates insulin-stimulated glucose uptake in muscle (12). This defect produces insulin resistance along with hyperinsulinemia as a compensatory response. Interestingly, the MAPK pathway is normal in these patients, leading to increased steroidogenesis with subsequent induction of hyperandrogenism. Therefore, insulin resistance could be responsible for the simultaneous occurrence of both metabolic and androgenic features of PCOS. Both lifestyle intervention and drug therapy have been found to increase insulin sensitivity, which, in turn, corrects hyperandrogenism and fertility outcomes in these patients (24).

In addition, results of the present study showed a positive significant correlation between BMI and two-hour post-load blood glucose. Similarly, Lankarani et al. reported that PCOS patients experience dyslipidemia and obesity more frequently than the general population, which subjects them to an increased risk of diabetes, dyslipidemia, and hypertension (25). Therefore, it is important to educate the patients regarding lifestyle modification, dietary changes, and exercise.

The need for diagnosing and follow-up on IGT in PCOS patients was also emphasized in a 2019 prospective cohort study by Ng et al. There, 199 PCOS women and 225 controls were followed up for 10 years. In addition to that, the following were highlighted as the main concerns in dealing with PCOS patients based on the aforementioned management practices. Prevalence of IGT in the PCOS population was demonstrated to rise from 31.7% to 47.2% on follow-up (26). These findings confirm that PCOS is a chronic, progressive disease of metabolic well-being and should be treated early.

In an attempt to reduce errors due to missing data from medical records, this study was planned prospectively. In addition to departmental faculty members, FBG and OGTT were ordered for all patients to provide methodologic consistency and data comparability. A key limitation of this study was the high cost of administering these tests to the initially planned control group (225 subjects), which because of financial limitations had to be cut down to 55 subjects.

4.1. Conclusions

In this study, the prevalence of IGT was higher among women with PCOS than among controls; however, this difference did not reach statistical significance. Women with PCOS nonetheless exhibited significantly higher mean 2-hour post-load glucose levels, indicating early alterations in glucose metabolism. These findings highlight the importance of metabolic screening in women with PCOS to facilitate early detection of metabolic abnormalities. Given the combined impact of PCOS on fertility and metabolic health, patient education, regular follow-up, and timely lifestyle or pharmacologic interventions may be effective in reducing long-term complications.