1. Introduction

Human cytomegalovirus (hCMV), a highly widespread herpesvirus, causes lifelong latent infections with periodic reactivation. Affecting 60 - 90% globally, hCMV is often asymptomatic in healthy individuals but poses risks to the immunocompromised, neonates, and transplant recipients (1). As a leading cause of congenital infections, it can result in birth defects and neurological issues. Its complex genome encodes proteins for immune evasion and replication (2). This narrative review aims to synthesize current knowledge on the molecular pathogenesis and clinical impact of hCMV, providing a unified resource for understanding diagnostics, treatments, and prevention (3).

2. Biology of Human Cytomegalovirus

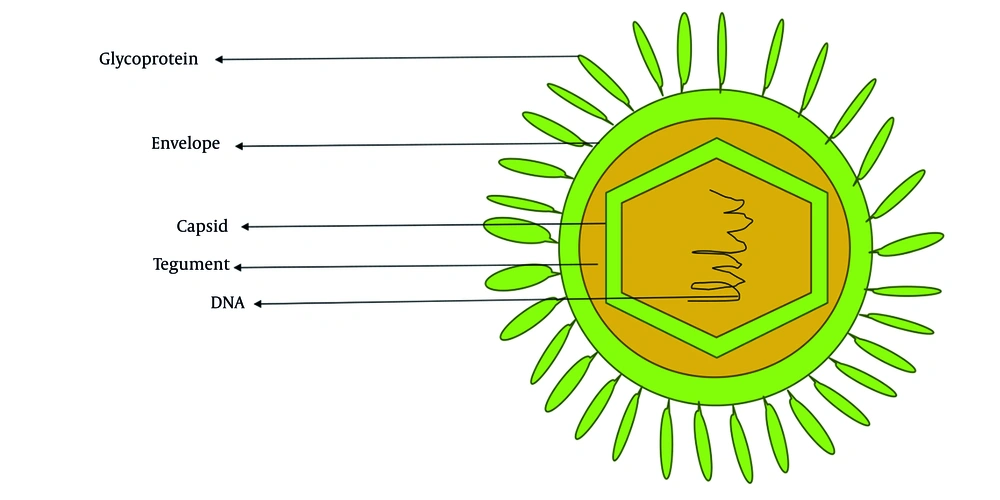

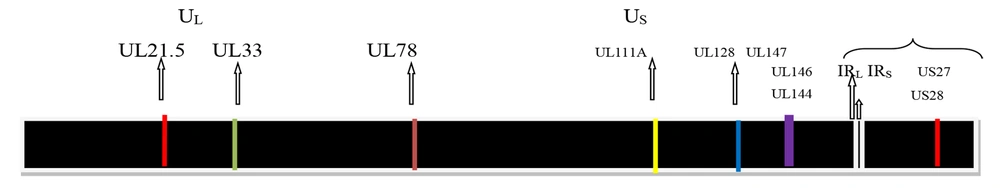

Cytomegalovirus (CMV), or human herpesvirus 5 (HHV-5), derives its common name from the characteristic cytopathic effect it induces in infected cells, cyto (cell) megalo (enlargement), resulting in enlarged (cytomegalic) cells with intranuclear inclusions (4). It is a member of the Herpesviridae family and is classified within the Betaherpesvirinae subfamily and genus Cytomegalovirus (5). The virion is characterized by a spherical morphology, a double-stranded linear DNA genome encased within an icosahedral capsid. This core structure is enveloped by a tegument layer and a lipid bilayer membrane as shown in Figure 1. Figure 2 shows the genome of CMV, approximately 230 kilobases in size, characterized by unique long (UL) and short (US) regions (6). The hCMV genome has UL and US regions with inverted repeats. These regions contain most viral protein-coding genes. The UL region encodes proteins for replication (DNA polymerase UL54) and structure (major capsid protein UL86). The US region is key for pathogenesis, containing immune evasion genes [US2-US11, downregulating major histocompatibility complex (MHC) I and II] (7). Inversion of these regions creates four isomers, potentially increasing genetic flexibility and tropism. Cytomegalovirus encodes over 200 viral proteins from more than 751 open reading frames and exhibits a temporal gene expression cascade classified into immediate early (IE), early (E), and late genes (8). The major capsid protein, triplex dimer and monomer, and the smallest capsid protein form the core capsid proteins, with additional structural components in the tegument and envelope facilitating virion assembly and packaging (9).

2.1. Mode of Transmission of Human Cytomegalovirus

Cytomegalovirus is transmitted through direct contact with infected bodily fluids such as saliva, urine, blood, breast milk, semen, and tears, particularly during childbirth. Intermittent viral shedding occurs frequently in infants, children, and pregnant women, increasing the risk for pregnant childcare workers (10). Other transmission methods include inhalation, fomite spread, and sexual contact, with organ transplantation and blood transfusion being less common. Human CMV infection can result from primary infection, reinfection, or reactivation, potentially affecting various organs, including the lungs, liver, retina, muscles, brain, and gut (10).

2.2. Epidemiology of Human Cytomegalovirus Infection

Cytomegalovirus is a widespread virus affecting 40 - 60% of adults in western countries and up to 100% in developing nations. Congenital CMV infection affects 0.15 - 2.0% of newborns, with 30% showing symptoms. High-risk populations include organ transplant recipients and immunocompromised individuals, particularly those with hematological disorders (over 80% prevalence in the western Brazilian Amazon) (11). In developing regions like Africa and Nigeria, CMV causes significant congenital infections, pneumonia, and meningitis, with prevalence rates among pregnant women ranging from 84.2% to 98.7% across different Nigerian cities, indicating an increasing trend (12).

2.3. Life Cycle of Human Cytomegalovirus

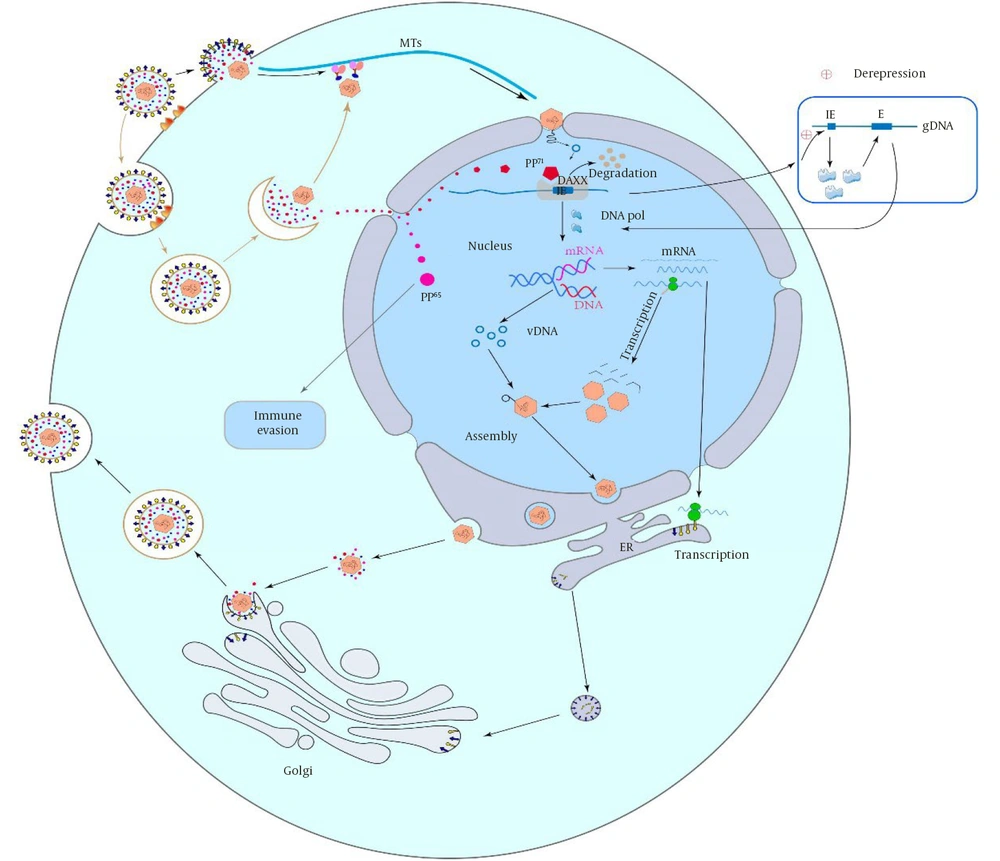

Human CMV initiates infection by attaching to host cells via glycoproteins and receptors, entering through membrane fusion or endocytosis. Trimers facilitate pH-independent fusion in fibroblasts via PDGFRα, while pentamers use low pH-dependent endocytosis in epithelial/endothelial cells via Nrp2 (13). CD47, CD46, and OR14I1 mediate epithelial entry. Human CMV targets the nucleolus, transporting its capsid to the nucleus via microtubules, with tegument proteins (pp65, pp71) aiding replication/gene expression. After capsid dissociation and DNA release, E proteins drive gene expression, and late proteins are synthesized post-replication. Tegument proteins regulate host response, late gene expression initiates capsid assembly, which matures and is released (14).

Figure 3 illustrates the major steps of human cytomegalovirus infection, ranging from attachment and entry into the hosT-cell to release of new viral particles into host cells. These phases range from divergent mechanisms of viral entry to specific phases of late gene expression (15).

2.4. Pathogenesis of Human Cytomegalovirus

Human CMV infects a wide range of human organs and tissues. Replication in cytotrophoblasts disrupts differentiation, impairs villi development, causes placental abnormalities, and hinders the transport of oxygen and nutrients to the fetus, which may result in intrauterine growth restriction (IUGR) (16). Brain injury is attributed to viral replication, immune-mediated damage by CD8+ T-cells, and placental insufficiency, all of which affect neural stem cells, neuronal migration, and brain organization. Chronic hCMV infection can induce persistent inflammation, potentially contributing to cardiovascular diseases and cancers in immunocompetent individuals (17). Primary or active infections are associated with severe diseases in immunotolerant individuals, such as arteriosclerosis, colitis, various cancers, and retinitis. The pathogenesis of hCMV involves viremia, viral load thresholds, immune evasion, latency, and the expression of genes that facilitate immune escape, including viral IL-10 homologs. Epithelial and endothelial cells are the principal targets, and hCMV establishes lifelong latency (18).

2.5. Immune Response to Human Cytomegalovirus Infection

The innate immune system, comprising natural killer (NK) cells, dendritic cells, and macrophages, is critical in defending against hCMV by detecting the virus via pattern recognition receptors (PRRs) that trigger interferons (IFNs) and pro-inflammatory cytokines (19). The DNA sensor cGAS transmits infection signals, but hCMV evades this response using tegument proteins such as UL82, UL31, UL83, and IE proteins IE1 and IE2. Adaptive immunity is essential for controlling primary infection, with the US2-US11 viral region encoding glycoproteins that interfere with antigen presentation by downregulating MHC class I molecules. Additionally, hCMV microRNAs (miRNAs) target proteins involved in antigen processing to evade immune detection (20).

2.6. Immune Evasion Mechanisms

Human CMV employs complex immune evasion strategies to disrupt both innate and adaptive immunity, enabling persistent, lifelong infection by avoiding detection and antiviral defenses (20).

2.6.1. Inhibition of Pattern Recognition Receptors

Human CMV suppresses the cGAS-STING DNA sensing pathway via proteins which include UL82 (pp71) and UL31, which prevent cGAS activation or degrade STING, and toll-like receptor (TLR) signaling, in which hCMV proteins (e.g., UL36) deubiquitinate signaling molecules (TRAF6, TRAF3) to inhibit NF-κB and IRF3 activation (21).

2.6.2. Blocking Interferon Responses

The disruption of interferon-gamma (IFN-γ) signaling, IE1 (UL123) binds to STAT2, US9 degrades MAVS to inhibit RIG-I/MDA5 signaling, and TRS1/IRS1 bind to and inhibit PKR to prevent translational shutdown (22).

2.6.3. Inhibition of Natural Killer Cell Activity

In order to inhibit NK cell activation, UL16, UL18, and UL40 bind to NKG2D and HLA-E, UL141 downregulates CD155 (an NK cell ligand) to evade NK-mediated killing, and US18/US20 promote the degradation of MICA/B, which are ligands for NKG2D (23).

2.6.4. Major Histocompatibility Complex Class I Downregulation (Avoiding CD8+ T Cells)

The viral proteins US2, US3, US6, and US11 facilitate the degradation or endoplasmic reticulum retention of MHC class I molecules (24).

2.6.5. Major Histocompatibility Complex Class II Inhibition (Avoiding CD4+ T Cells)

Proteins US2 and US3 target MHC class II molecules for degradation, whereas UL111a encodes a viral interleukin-10 homolog (cmvIL-10) that suppresses the expression of MHC class II (25).

2.6.6. Disruption of Antibody Responses

The protein gp68 (UL119-UL118) binds to Fc gamma receptors, thereby blocking antibody-mediated neutralization. In addition, TRL11/IRL11 function as viral Fc receptors that prevent immunoglobulin G (IgG) binding (26).

2.6.7. Modulation of Apoptosis and Cell Survival

The protein vMIA (UL37x1) inhibits mitochondrial apoptosis by blocking the functions of BAX and BAK. In addition, vICA (UL36) acts as a caspase-8 inhibitor, preventing apoptosis induced by death receptors. Furthermore, the IE protein IE2 (UL122) upregulates anti-apoptotic genes, including Bcl-2 (27).

2.6.8. Manipulation of Cytokines and Chemokines

The protein mvIL-10 (UL111a) mimics human interleukin-10 to suppress inflammation and inhibit antigen presentation. Additionally, US28 functions as a viral chemokine receptor that scavenges chemokines, such as CCL5, to block the recruitment of immune cells. Moreover, UL146 and UL147 encode viral chemokines (vCXCL1) that modulate the migration of neutrophils (28).

2.6.9. Latency and Reactivation Control

Latency-associated transcripts (LUNA, UL138) maintain the viral genome in hematopoietic progenitor cells without producing virions, miRNAs (e.g., miR-UL112-1) target viral and host genes to suppress lytic replication and immune detection, and IE1/IE2 regulate viral reactivation from latency in response to immune suppression (29).

2.7. Clinical Manifestations and Management of Human Cytomegalovirus

Human CMV exhibits a multi-systemic effect, affecting various tissues and organs, including the lungs, liver, retina, muscles, brain, and gastrointestinal tract. Latency may result in asymptomatic infections, while viral activation can lead to a range of symptoms, including fever, encephalitis (characterized by seizures and coma), pneumonia with associated hypoxemia, hepatitis, extensive ulcerations, dyspnea, and visual disturbances (30).

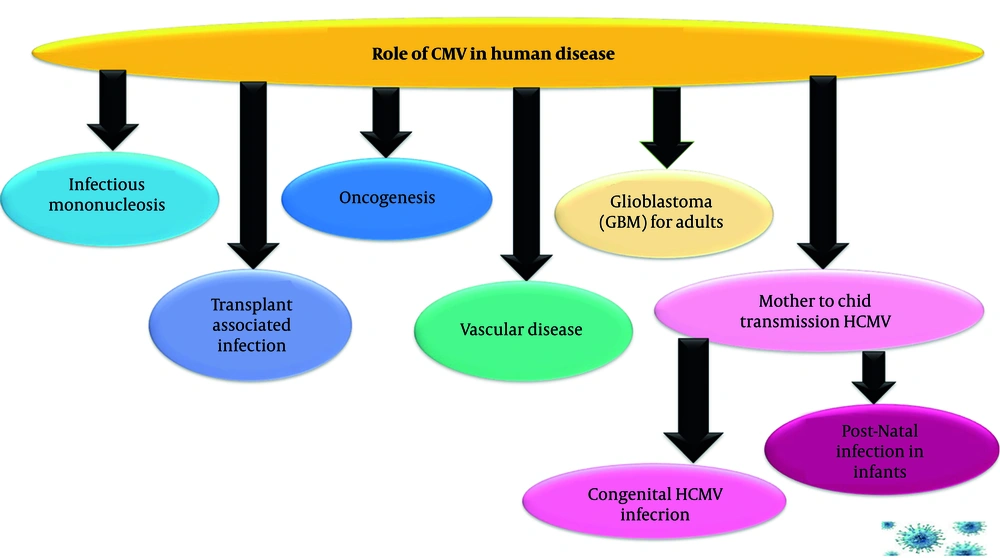

Figure 4 illustrates the wide range of health problems caused by CMV, a common virus that can affect different populations in specific ways. It shows that CMV is not a single-disease virus. Its impact ranges from mild illness in healthy people to severe, life-threatening conditions in unborn children, transplant patients, and through its potential links to chronic diseases like cancer and vascular illness.

2.7.1. Infectious Mononucleosis

Human CMV infection often presents as a self-limiting febrile illness resembling Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) mononucleosis. Mononucleosis differs by less frequently presenting with pharyngitis, adenopathy, and splenomegaly. Symptoms include fever, malaise, myalgia, headache, and fatigue. Some patients experience splenomegaly, hepatomegaly, adenopathy, and rash. Laboratory tests show lymphocytosis, atypical lymphocytes, and abnormal liver function (31).

2.7.2. Transplant-Associated Infection

Human CMV is one of the most significant infectious complications, impacting graft survival and patient mortality in transplant recipients. Viral reactivation is common post-transplant, increasing hospitalization costs. Primary CMV infection is more complicated than reactivation/reinfection. It causes direct end-organ disease (pneumonitis, colitis, hepatitis, retinitis) and indirect effects such as graft rejection, vasculopathy, opportunistic infections, and post-transplant lymphoproliferative disorder (PTLD). Prevention includes universal prophylaxis (antivirals like valganciclovir/letermovir) or preemptive therapy [quantitative polymerase chain reaction (qPCR) monitoring and treatment upon threshold breach]. Pre- and post-transplant screening and antiviral use are standard, but late-onset CMV remains a problem (32).

2.7.3. Infection in Immunocompromised (HIV/AIDS)

Human CMV is a leading opportunistic pathogen in acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS), linked to HIV progression. Before highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART), 40% of adults and 10% of children with AIDS had CMV manifestations like retinitis, esophagitis, and colitis. Encephalitis, neuropathy, pneumonitis, gastritis, and liver dysfunction were also reported. Pathogenesis is due to a loss of immune suppressor function and reactivation, although hCMV is also a co-factor for advancement of immunodeficiency through promotion of HIV replication. The mainstay of prophylactic therapy is immune restoration by HAART, supplemented by secondary antiviral therapy for severely immunocompromised individuals until the CD4+ numbers improve (33).

2.7.4. Role of Human Cytomegalovirus in Oncogenesis

The role of hCMV in cancer is debated. It may play a role in tumour regulation and metastasis, with high prevalence in brain metastases from breast and colorectal cancers. It is unclear if CMV causes cancers, as it does not transform normal cells. However, it possesses molecular hallmarks of tumour viruses. Human CMV might create "smouldering inflammation," promoting oncogenesis, or act as an "oncomodulator," enhancing malignancy. Cytomegalovirus DNA and antigens are found in tumour cells of colorectal, glioma, prostate, and breast cancers. Higher hCMV infection correlates with lower life expectancy in glioblastoma (GBM) patients. It can also promote angiogenesis, alter the cell cycle, inhibit apoptosis, and influence invasion/migration (34).

2.7.5. Role of Human Cytomegalovirus in Cardiovascular Diseases

Cytomegalovirus may contribute to inflammatory cardiovascular diseases. Studies link CMV and atherosclerosis, with higher antibody titers in patients with carotid intima-media thickness (IMT). It infects endothelial cells, smooth muscle cells, and monocytes. Monocytes become foamy macrophages in arteries. Cytomegalovirus alters monocyte function. Animal studies link CMV to endothelial damage, monocyte infiltration, foam cell accumulation, vascular disease, and promote vascular disease at multiple stages (35).

2.7.6. Glioblastoma for Adults

Human CMV is a potential GBM pathogen. Glioblastoma expresses CMV proteins. It can induce GBM formation in vitro and in xenograft models and can also be detected in GBM from patients. The effect of CMV is controversial due to low viral levels. Studies suggest a high infection rate in GBM patients, with explored mechanisms including oncomodulation and immune regulation (36).

2.8. Laboratory Diagnosis of Human Cytomegalovirus

Techniques for detecting hCMV are improving rapidly, and nucleic acid tests such as the polymerase chain reaction (PCR), branch DNA (bDNA), and nucleic acid sequence-based amplification (NASBA) are now available at larger centres. Serological tests are highly specific and sensitive, although antibody can decline with age and severe immunosuppression, IgG seropositivity is usually lifelong (37).

Congenital CMV diagnosis requires virus detection (culture/PCR) in bodily fluids (saliva/urine preferred) within 2 - 3 weeks of life. Later diagnosis cannot differentiate between congenital and postnatal infection. Saliva PCR is sensitive/specific while urine PCR is reliable. Dried blood spots (DBS) are less sensitive and mainly useful for retrospective diagnosis. In immunocompromised patients, qPCR in plasma/blood is primary for active infection diagnosis while pp65 antigenemia assay is an alternative but less common (38).

Human CMV diagnosis uses cell cultures, microscopy, and serology. Antigen detection and qPCR are key for detecting active infection and monitoring viral load, especially in immunocompromised patients. Immunofluorescence and nucleic acid hybridization are also useful, with test selection guided by clinical factors (39), as shown in Table 1.

| Test Category | Key Methods | Advantage |

|---|---|---|

| Viral culture | Cell culture (fibroblasts) | Gold standard for detecting active, replicating virus; Slow. |

| Serology | ELISA, Latex Agglutination, IgM capture | Determines serostatus (IgG) and recent infection (IgM); Cannot distinguish latent/active. |

| Antigenemia | pp65 detection in leukocytes | Rapid detection of active infection; Useful for preemptive therapy monitoring. |

| Molecular methods | qPCR, NASBA, bDNA | High sensitivity/specificity; Gold standard for viral load monitoring in immunocompromised. |

| Histology | Microscopy (H&E, IHC), In-situ hybridization | Detects characteristic "owl's eye" inclusions or viral DNA/proteins in tissue. |

Abbreviations: IgG, immunoglobulin G; qPCR, quantitative polymerase chain reaction; NASBA, nucleic acid sequence-based amplification; bDNA, branch DNA;

2.9. Treatment of Human Cytomegalovirus Infection

2.9.1 Pharmacological Therapy

Cytomegalovirus infections resolve without treatment in adults. However, antiviral drugs, like ganciclovir, can help children and immunocompromised adults by reducing viral replication and transmission, especially in congenital or recurrent cases. Hospitalization may be needed for ganciclovir-related organ damage (40).

Several antiviral drugs are the main treatment for hCMV. These drugs mostly target the viral DNA polymerase (UL54). Ganciclovir, a deoxyguanosine analog, and its oral form, valganciclovir, stop viral DNA synthesis by acting as chain terminators. However, using these drugs is limited because they can cause dose-related blood problems, like low white blood cell count (neutropenia) and low platelet count (thrombocytopenia). Cidofovir, another nucleotide analog, also blocks DNA polymerase but can harm the kidneys. Foscarnet works differently by directly attaching to the polymerase's pyrophosphate site. This means it does not need to be activated by viral kinases. However, foscarnet can often cause kidney problems and electrolyte imbalances. A major concern with ganciclovir and valganciclovir is that they might cause cancer (41).

2.9.2. Non-pharmacological Treatment

2.9.2.1. Nucleic Acid-Based Gene Targeting Approach

Nucleic acid-based gene targeting strategies, such as transcription activator-like effector nucleases (TALENs), clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats/CRISPR-associated protein 9 (CRISPR/Cas9) nuclease system, and external guide sequences-ribonuclease (EGSs-RNase), may offer potential for treating hCMV infections by targeting vital genes. These strategies may enhance the removal of latent infections, which are currently untreated. Developing novel antiviral methods for treating latent infections is crucial, as no current treatments have progressed to clinical trials (42).

2.9.2.2. Adoptive T-cell Therapy for Transplantation Recipients

Adoptive T-cell therapy (ACT) for hCMV aims to reduce infection-related morbidity by expanding specific T-cells ex vivo, offering benefits for transplant patients with recurrent or drug-resistant virus. However, its clinical evaluation faces challenges from concurrent therapies and requires further controlled studies and long-term monitoring (43).

2.9.2.3. Immunotherapy for Glioblastoma Patients

Human CMV antigens in GBM enable pp65-specific T-cells to target tumor cells, showing promising immunotherapy potential. Establishing clinical efficacy requires combined therapies and long-term patient monitoring (44).

2.10. Prevention and Control of Human Cytomegalovirus

2.10.1. Pharmacologic Prevention

Allogeneic transplant recipients should receive prophylactic or pre-emptive treatment. Use leukocyte-reduced or CMV-negative blood for at-risk recipients; consider leukocyte-depleted/filtered blood for immunosuppressed patients (45).

2.10.2. Vaccine

Recent phase II trials suggest hCMV vaccine success is possible, despite complex immune interactions. A gB vaccine with MF59 showed approximately 50% protection against seroconversion in postpartum women and reduced viremia/therapy needs in transplant candidates. Anti-gB antibody titre correlated with protection. An earlier study also showed promise with a live attenuated vaccine. Human CMV vaccine strategies include messenger RNA (mRNA) vaccines (Moderna's mRNA-1647) targeting gB and gH/gL/UL128/UL130/UL131A for broad antibody response; viral vectors [modified vaccinia Ankara (MVA)] delivering pp65/IE1 to stimulate T-cell immunity and dense body vaccines using subviral particles for antibody and T-cell responses (46).

2.10.3. Non-pharmacologic Prevention

Cytomegalovirus can be prevented by avoiding contact with body fluids, practicing hand hygiene, and following standard precautions. High-risk individuals and pregnant women need medical advice and/or formal prevention programs.

2.11. Recent Advances and Future Perspectives

Recent advances have improved our understanding of hCMV pathophysiology, identifying viral and host genetic factors influencing lytic, latent, and reactivation stages. Integrating this knowledge into new diagnostics could improve viral load quantification in tissues, differentiate infection stages, detect reactivation, and identify antiviral resistance. Increased institutional, financial, and educational support is crucial for accelerating innovative diagnostic and therapeutic strategies for this common and deadly infection (47).

2.11.1. Novel Antiviral Drugs

Letermovir is approved for the prophylaxis of hCMV infection in adult recipients of hematopoietic stem cell or solid organ transplants. It is utilized in the treatment or prevention of acute hCMV infections. Clinical trials have established its efficacy in infected patients, including those with AIDS or transplant recipients. Maribavir may be considered for the treatment of post-transplant hCMV infections in adult patients who exhibit refractoriness, with or without genotypic resistance, to prior antiviral therapies. They can provide several routes of administration, lessen drug/cross-resistance, and cause fewer side effects (48).

Tomeglovir, an oral non-nucleoside inhibitor, targets pUL56, like letermovir, but has a different binding site. It is a potential prophylactic and therapeutic for letermovir-resistant virus. Brincidofovir (CMX001), a lipid-conjugated cidofovir prodrug, has improved bioavailability and reduced renal toxicity; its development for other viruses and future hCMV applications are of interest. Filociclovir (CX-01), a nucleoside analog, inhibits viral DNA polymerase and is active against ganciclovir/cidofovir-resistant hCMV strains in pre-clinical studies, and it has undergone early-phase clinical testing (49).

2.11.2. The Combination of Drugs

Human CMV infections may benefit from the combination of antiviral medications; however, this therapeutic approach's effectiveness is still unknown. The efficacy of the medication combination, while suggestive, lacks conclusive evidence compared to monotherapy and is supported by limited in vitro data. Further research is needed to establish the superiority of combination therapy over monotherapy, especially in the prevention or treatment of hCMV resistance; more and more findings from in vitro, in vivo, and clinical trials are needed (50).

2.11.3. Gene-Targeting Approaches and Cell Therapy

Gene targeting, though early in development, could aid human medicine. Limited selectivity, mutation risk, and delivery issues restrict clinical use. In urgent cases lacking treatment options, gene targeting's compassionate use is more acceptable. Adoptive ACT may prevent/treat hCMV in transplant recipients. Successful cases support immunotherapy for GBM and ACT for transplant recipients, highlighting hCMV's role. Cell therapies may be conditionally approved when alternatives are lacking or benefits outweigh risks (51).

2.11.4. Human Cytomegalovirus Vaccine

Human CMV vaccine development explores gene deletion strategies, inspired by a mouse model where M33 G protein-coupled receptor (GPCR) removal attenuated the virus and provided protection as an olfactory vaccine. This approach may yield a safe vaccine preventing congenital infections and severe disease. However, obstacles remain, including immune evasion, unclear correlates of protection, insufficient memory cell protection, limited animal models, low public awareness, and target population identification (52).

3. Search Strategy and Methodology

This article is a comprehensive narrative review of the literature on hCMV; a detailed strategy was implemented to identify relevant studies. This search utilized various scholarly databases, including PubMed, Scopus, Springer, ScienceDirect, Web of Science, Google Scholar, and ResearchGate. The search was limited to articles published in English, with a primary focus on literature from January 2000 to July 2024 to ensure the inclusion of contemporary research, while also allowing for the inclusion of seminal older publications. The key search strings included, such as "Human Cytomegalovirus," "hCMV infection," "hCMV pathogenesis," "hCMV treatment," and "immune response to hCMV." The search utilized a combination of keywords and Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) terms related to hCMV. This approach ensured the inclusion of all pertinent literature, covering areas such as virology, clinical implications, diagnostics, therapeutic options, and the interactions between the immune system and hCMV.

The initial search yielded (120) articles. Titles and abstracts were screened for relevance, resulting in (95) articles for full-text review. After full-text assessment, (59) articles were included in this review. The study included and extracted original research articles (in vitro, in vivo, clinical trials), authoritative review articles, meta-analyses, and clinical guidelines focusing on hCMV virology, pathogenesis, clinical manifestations, diagnosis, management, and prevention. Exclusion criteria comprised studies on non-hCMV strains lacking direct relevance to human infection, articles not published in English, conference abstracts lacking full-text availability, and studies exhibiting poor methodological quality as assessed by the author. Data were subsequently organized thematically to structure the review. Furthermore, the reference lists of key articles were manually searched to identify potentially relevant additional resources.

4. General Discussion

This comprehensive review has synthesized the complex landscape of hCMV from basic virology research to the complexities of its management. Several critical themes and challenges emerge from this synthesis that are central to the current and future understanding of this pathogen. The complex interplay between viral immune evasion mechanisms and host immune functions is in itself a paradigm as outlined in detail in section 2.6, hCMV expresses numerous proteins whose cumulative function in immune system evasion corresponds to the destruction of both innate and acquired immunity (25).

Many studies have analyzed some components such as the reduction of MHC Class I surface expression induced by US2-11 or immune evasion by UL16 and UL141 in NK cells, which is an accurate quantification of the cumulative in vivo effectiveness of such mechanisms, but it has not yet been fully explored. Providing immune protection against reactivation or congenital infections would logically require a vaccine-stimulated immune response superior in breadth or strength to the immune reaction induced by the virus itself (53).

The challenge of translating diagnostic capability into clinical outcomes will continue to persist. Advances in highly sensitive qPCR (section 2.8) have brought about significant changes in following up patients who are immunocompromised. But, as evidenced in different studies, there is no universal viral load at which the onset of clinical disease can reliably be forecast in all patient categories (stem cell vs. solid organ transplant recipients alike). In addition, there are challenges in distinguishing between latent and active infections without employing invasive tissue biopsies, which will assume importance in illnesses such as hCMV -associated GBM (54).

Conventional medications such as ganciclovir have remained the backbone of treatment ever since; today the current state of treatment represents a critical turning point characterized by both advances and challenges. The emergence of new antivirals such as letermovir and maribavir (section 2.9) marked the beginning of a paradigm shift. Their mechanisms of action offer critical complementarity to treatment in cases where resistance to conventional antivirals has developed. Success in these antivirals has resulted in new challenges. Issues such as how these drugs can be appropriately combined and how there can be no resistance to these drugs have emerged (55).

The persistent viral reservoir in hCMV infections remains a key challenge in the development of effective hCMV therapies. As described in section 2.9.2, promising research directions such as the use of the gene editing tool clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats/CRISPR-associated protein 9 (CRISPR/Cas9) or adoptive T-cell transfer target the elimination of viral reservoirs or controlling viral reactivation by immune modulation. Although intriguing, evaluating these topics illustrates that all are strictly in the early stage of development, or at most in early-stage clinical trials. Indeed, there is much translational work remaining in these directions (56).

However, this level of complexity is also evident in the protracted search for an hCMV vaccine, which has been ongoing for several decades (section 2.10.2). The partial success of the gB/MF59 vaccine has shown that prevention can work but has also indicated how little we know about immune correlates of protection. The most fundamental question therefore carries forward: Will protection against hCMV rely on antibody or T-cell responses? Any future vaccine needs therefore to aim at resolving such fundamental issues (57).

Combination therapy (section 2.11.2) underscores the importance of strategic thinking in its application. The aim of taking combined drugs to prevent resistance development makes perfect sense in theory; there are very few clinical data in support of the same. Will the future of hCMV treatment in complex cases go with the HIV treatment model of taking multiple drugs at the same time? The need, in fact, points out towards further research in this area (58).

4.1. Conclusions

Human CMV infection is a significant cause of diverse diseases, especially in immunocompromised patients, pregnant women, and neonates, where it can lead to serious medical complications. The future of hCMV research and treatment represents a shift away from the reactive approach of using non-specific and highly toxic agents towards a strategic approach based on antiviral drugs, immune modulators, and preventative vaccines. The challenges facing current antiviral drugs today are less about antiviral activity and center around issues of long-term management, preventing resistance, and ultimately eliminating the latent virus (59).

4.2. Limitation of the Study

This comprehensive narrative review has some limitations. It is intended to provide a unified overview, but it can lead to the omission of some highly specialized or recent studies. As a narrative review, the selection of literature, which is guided by a systematic search strategy, does not carry the formal methodological rigor of a systematic review or meta-analysis. Furthermore, the rapid pace of discovery in areas such as antiviral development and immunotherapy means that some very recent advances may not be fully captured.