1. Introduction

Dysmenorrhea is divided into two types: Primary and secondary dysmenorrhea. Primary dysmenorrhea (PD) refers to pain that occurs in the absence of pelvic pathology during menstruation, while secondary dysmenorrhea is generally caused by reproductive system disorders, including endometriosis, uterine myoma, adenomyosis, cervical stenosis, pelvic inflammatory disease, and pelvic adhesions (1). The factors associated with dysmenorrhea include early menarche, family history, duration of bleeding, smoking, stress, and low Body Mass Index (2-4). The prevalence of PD in women of reproductive age varies significantly, ranging from 16% to 91%. It has been reported that 2% to 29% of patients experience severe dysmenorrhea (3). In adolescence, the prevalence of dysmenorrhea is relatively higher and reaches approximately 75% (5). The prevalence of dysmenorrhea in Iran is reported as 71% (6). Dysmenorrhea can exert negative effects on quality of life (7), performance, sports activities, and social relationships (8). The first line of treatment for dysmenorrhea is nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs). Of course, other oral and non-oral treatments have been suggested for PD; nonetheless, there is still insufficient evidence to confirm their effectiveness (9). The NSAIDs are effective in relieving the pain of PD. Nevertheless, they can have side effects such as nausea, dyspepsia, stomach ulcers, and diarrhea (10). Herbal products, or phytomedicines, are currently the main alternatives for women who want pain relief without side effects. One of the herbal medicines usually used to reduce menstrual pain is ginger. According to Rahman et al., ginger tea warms the body and acts as an anti-rheumatic, anti-inflammatory, and analgesic (11).

Fennel is also an herbal medicine that can be effective in the treatment of dysmenorrhea (12). Cinnamon is one of the plants known as a pain reliever in traditional medicine. This plant is recommended due to its multiple properties, such as being anti-flatulent, diuretic, carminative, an appetizer, a stomach tonic, disinfectant, anti-swelling, and a pain reliever (13, 14). Today, considering the various side effects of chemical drugs, it is crucial to provide a non-drug treatment method for young patients who do not respond to medicines, suffer from their side effects, or do not want to take drugs and hormones (15). In a previous meta-analysis, Xu et al. (2020) evaluated nine studies aimed at assessing the effectiveness of herbal medicines (cinnamon/fennel/ginger) in the treatment of PD (16). In the current study, the number of studies has doubled, and the total number of participants has also increased. In the previous meta-analysis, the control group included only the placebo; nonetheless, in the present meta-analysis, in addition to the placebo, routine medicines and exercise were also considered. The effect of different doses of herbal medicines was not evaluated in the previous meta-analysis, and this limitation was resolved in the current meta-analysis. In the previous meta-analysis, all studies were randomized controlled trials (RCTs); however, quasi-experimental studies and clinical trials were examined in our meta-analysis.

In addition, studies by Adib-Rad and Augustian showed that there was no significant association between ginger consumption and the reduction of pain caused by PD (17, 18). Conversely, some other studies suggested that ginger consumption reduces pain caused by PD (19, 20). Regarding fennel, Delaram's study indicated that fennel reduces pain from PD (21), while other studies did not report a significant association between fennel consumption and pain reduction from PD (22, 23). Studies by Jahangirifar et al. and Habibian and Safarzadeh also showed that cinnamon can reduce pain caused by dysmenorrhea (24, 25) whereas Jaafarpour et al.'s study reported the opposite result (26).

2. Objectives

Due to the contradictory results of previously published studies and considering the limitations of previous meta-analyses, the current study was conducted using a systematic review and meta-analysis method to compare the effects of the three plants (cinnamon, fennel, and ginger) and provide an overall and up-to-date result. The reason for choosing these three herbs was that they are the most commonly used herbs for reducing the pain and duration of pain caused by PD.

3. Methods

The current systematic review and meta-analysis investigated the effect of cinnamon, fennel, and ginger on PD. This study was written according to the PRISMA reporting guidelines (27), and its protocol was registered on the PROSPERO website (CRD42023403525).

3.1. Search Strategy

In this study, the databases of Web of Science, PubMed, Cochrane, SID, Magiran, IranDoc, and Google Scholar search engines were searched without a time limit using the following MeSH keywords: Dysmenorrhea, Menstrual Pain, Painful Menstruation, Cinnamon, Cinnamomum zeylanicum, Ginger, Zingiber officinale, Fennel, and Foeniculum. References were searched until February 5, 2023. Articles published in Persian and English were reviewed. Combinations of these keywords were searched using (AND, OR) operators. The list of sources of reviewed studies was also screened and searched. For example, the search strategy in PubMed is as follows: (Dysmenorrhea [Title/Abstract] OR Menstrual Pain [Title/Abstract] OR Painful Menstruation [Title/Abstract]) AND (Cinnamon [Title/Abstract] OR C. Zeylanicum [Title/Abstract] OR Ginger [Title/Abstract] OR Z. officinale [Title/Abstract] OR Fennel [Title/Abstract] OR Foeniculum [Title/Abstract]). The resource search phase was conducted without time limits (Table 1).

| Databases | Query |

|---|---|

| Web of Sciences | Dysmenorrhea OR Menstrual Pain OR Painful Menstruation (Topic) AND Cinnamon OR Cinnamomumzeylanicum OR Ginger OR Zingiberofficinale OR Fennel OR Foeniculum (Topic) |

| Cochrane | Dysmenorrhea OR Menstrual Pain OR Painful Menstruation in Title Abstract Keyword AND Cinnamon OR Cinnamomumzeylanicum OR Ginger OR Zingiberofficinale OR Fennel OR Foeniculum in Title Abstract Keyword - in Trials (word variations have been searched) |

| PubMed | [Dysmenorrhea (Title/Abstract) OR Menstrual Pain (Title/Abstract) OR Painful Menstruation (Title/Abstract)] AND [Cinnamon (Title/Abstract) OR Cinnamomumzeylanicum (Title/Abstract) OR Ginger (Title/Abstract) OR Zingiberofficinale (Title/Abstract) OR Fennel (Title/Abstract) OR Foeniculum (Title/Abstract)] |

Two researchers (M. F. and M. A.) independently conducted the source search phase. In case of disagreement about a study, they resolved the disagreements by consulting each other. PICO Components:

A. Population: Patients who used cinnamon, fennel, or ginger to treat pain caused by PD.

B. Intervention: Consumption of cinnamon, fennel, or ginger.

C. Comparison: Placebo, exercise groups, or patients who used routine drugs.

D. Outcome: The main outcome of this study was pain due to PD.

3.2. Inclusion Criteria

This research included quasi-experimental and clinical trial studies that investigated the effect of cinnamon, fennel, or ginger on PD using the Visual Analog Scale (VAS). Studies published in Persian or English were reviewed in this research.

3.3. Exclusion Criteria

Observational studies, studies with insufficient information for data analysis, duplicate studies, as well as studies that examined the effect of simultaneous use of several herbal medicines on dysmenorrhea, evaluated the results qualitatively, used instruments other than VAS, were of low quality, or did not offer full-text access. Abstracts and unpublished studies were also excluded from the review process.

3.4. Qualitative Evaluation

Two authors independently evaluated the clinical trial studies using the Cochrane quality assessment checklist (28). This checklist consists of seven different items, each of which evaluates one of the dimensions or types of important biases in clinical trials. Moreover, each item on this checklist has three options: Low risk, high risk, and unclear risk. The TREND tool was also used to evaluate the quality of quasi-experimental studies (29). After completing the risk of bias assessment in the studies, all cases of disagreement were resolved into a single option using consensus between the two assessors.

3.5. Data Extraction

At this stage, two independent researchers performed data extraction. The researchers entered the extracted data into a checklist that included the researcher, country, year of publication, number of participants, type of study, mean age, drug dose, type of drug used, comparison group, and the mean and standard deviation of pain intensity and duration. The pain intensity and duration scores were measured based on the VAS Scale. This tool is a valid scale used in many types of research to appraise pain intensity, including menstrual pain (30, 31). Its reliability varies from 0.76 to 0.97 in different studies (32). Scores of 0 and 10 indicate the absence of pain and the worst pain possible, respectively. Each participant also assessed pain duration to indicate the number of hours they experienced pain during the first three days of their menstrual cycle.

3.6. Statistical Analysis

The Standardized Mean Difference (SMD) Index indicates the influence of the association between the desired intervention and the outcome under research. The reviewed studies were combined according to the number of samples, mean, and standard deviation. The random-effects model was used in the current research. To evaluate the heterogeneity of the studies, the I2 Index was used. STATA 14 software was used for statistical analysis, and the significance level of the tests was considered P < 0.05.

4. Results

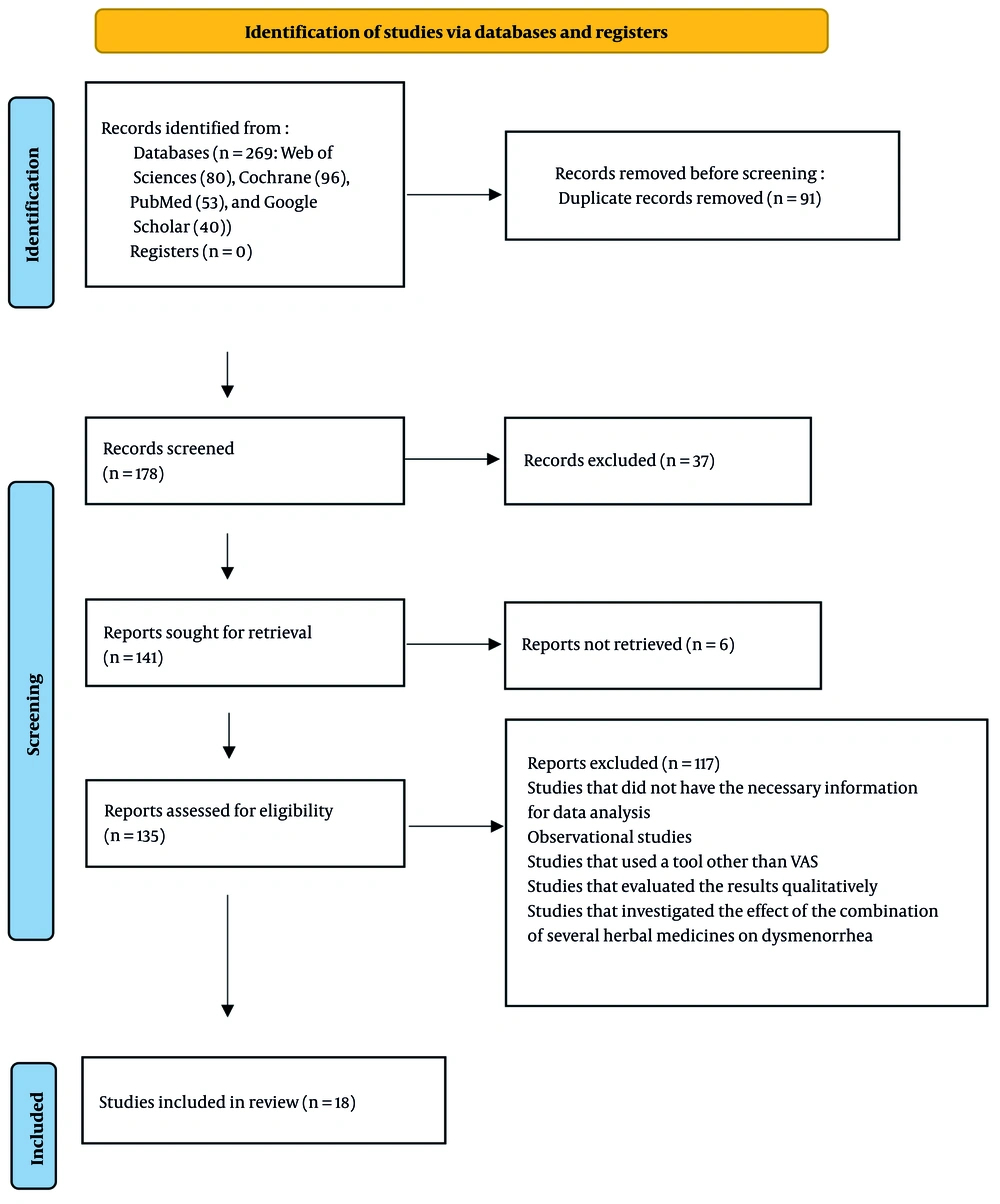

Firstly, a database search yielded 269 articles. The titles were reviewed, and 91 repeated researches were deleted. The abstracts of 178 researches were evaluated, and 37 researches were ruled out due to incomplete information in the abstract. The remaining 141 studies were reviewed, 6 of which were deleted due to the unavailability of the full text, another 117 studies were deleted due to other exclusion criteria, and 18 high-quality studies remained (Figure 1).

In this meta-analysis, 18 researches with a total number of 1,372 participants were evaluated. The studies were assigned to three categories, and each category investigated the effect of one of the following herbs: Cinnamon, fennel, and ginger on PD. All studies evaluated pain due to PD based on the VAS Scale. Among the above 18 articles, 4, 4, and 10 studies investigated the effects of fennel, cinnamon, and ginger, respectively (Table 2).

| Author, Year of Publication | Country | Type of Study | Quality Assessment | Number of Experiment Group | Number of Control Group | Mean Age of Experiment Group | Mean Age of Control Group | Type of Herbal Drug | Dose of Herbal Drug | Compared with |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Augustian, 2022 (18) | India | Quasi Experimental | High quality | 35 | 35 | 22.44 | 22.44 | Ginger | 500 mg | Exercise |

| Sultan et al., 2021 (33) | Pakistan | Clinical trial | low risk | 30 | 30 | 17.2 | 16.4 | Ginger | 250 mg | Placebo |

| Kinde and Tolasa, 2021 (19) | Ethiopia | Randomized comparative trial | low risk | 20 | 20 | 19 - 22 | 19 - 22 | Ginger | 200 mg | Exercise |

| Pakniat et al., 2019 (34) | Iran | Randomized clinical trial | low risk | 50 | 50 | 23.12 | 22.64 | Ginger | 1000 mg | Placebo |

| Pakniat et al., 2019 (35) | Iran | Single-blind clinical trial | low risk | 50 | 50 | 22.8 | 22.3 | Ginger | 500 mg | Placebo |

| Adib Rad et al., 2018 (17) | Iran | Cross-over clinical trial | low risk | 78 | 90 | 22.35 | 21.43 | Ginger | 200 mg | Novafen |

| Atashak and Rashidi, 2018 (36) | Iran | Quasi Experimental | High quality | 15 | 15 | 20.41 | 21.33 | Ginger | 250 mg | Placebo |

| Shirooye et al., 2017 (37) | Iran | Single-blind randomized trial | low risk | 35 | 35 | 22.9 | 23.1 | Ginger | 250 mg | Topical Ginger |

| Kashefi et al., 2014 (38) | Iran | Placebo-controlled randomized trial | low risk | 48 | 46 | 17 | 17 | Ginger | 250 mg | Placebo |

| Rahnama et al., 2012 (20) | Iran | Randomized, controlled trial | low risk | 59 | 46 | 21.4 | 21.3 | Ginger | 500 mg | Placebo |

| Mohamed et al., 2018 (39) | Egypt | Quasi-experimental | High quality | 53 | 57 | 17 - 18 | 17 - 18 | Fennel | A cup | Vitamin E |

| Zeraati et al., 2014 (23) | Iran | Double-blind clinical trial | low risk | 25 | 25 | 21.6 | 21.6 | Fennel | 30 drops of Fennelin 2% | Placebo |

| Bokaie et al., 2013 (22) | Iran | Randomized parallel group clinical trial | low risk | 29 | 30 | 21.07 | 21.17 | Fennel | 25 drops of Fennelin 2% | Mefenamic acid |

| Delaram and Sadeghian, 2011 (21) | Iran | Clinical trial | low risk | 28 | 26 | 19.92 | 20.23 | Fennel | 30 drops | Echinophora sibthorpiana |

| Habibian Safarzadeh, 2018 (25) | Iran | Quasi-experimental | High quality | 14 | 16 | 15 | 15.72 | Cinnamon | 500 mg | Exercise |

| Jahangirifar et al., 2018 (24) | Iran | Randomized, double-blind clinical trial | low risk | 40 | 40 | 22.2 | 22.3 | Cinnamon | 1000 mg | Placebo |

| Jaafarpour et al., 2015 (40) | Iran | Quasi-experimental | High quality | 38 | 38 | 20.7 | 21.3 | Cinnamon | 420 mg | Placebo |

| Jaafarpour et al., 2015 (26) | Iran | Randomized, double-blind clinical trial | low risk | 38 | 38 | 20.7 | 20.8 | Cinnamon | 420 mg | Ibuprofen |

4.1. Effect of Ginger on Primary Dysmenorrhea

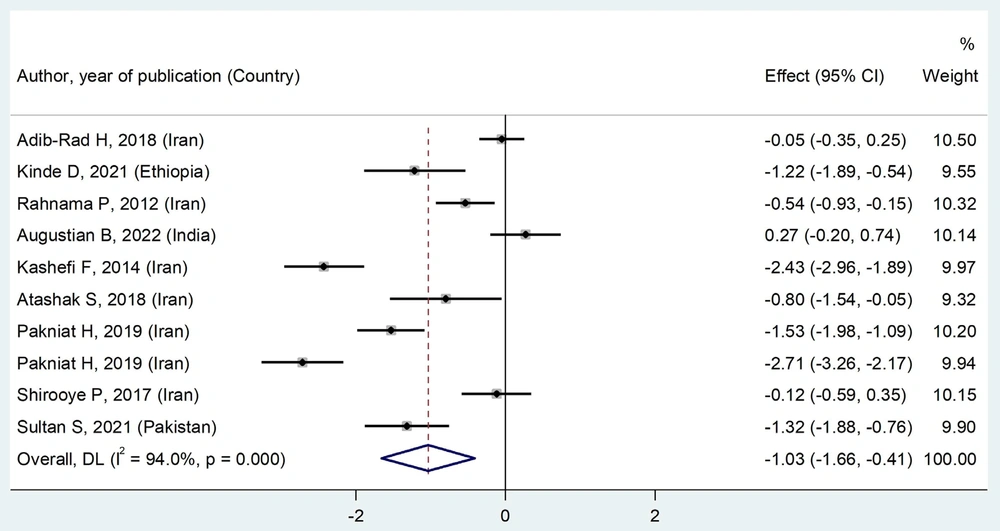

Before the intervention, there was no significant difference between the ginger and comparison groups in terms of pain intensity [SMD = -0.03 (95% CI: -0.16, 0.11), P = 0.542]. Nonetheless, after the intervention, the ginger group experienced a decrease in pain intensity compared to the comparison group [SMD = -1.03 (95% CI: -1.66, -0.41), P = 0.000] (Figure 2).

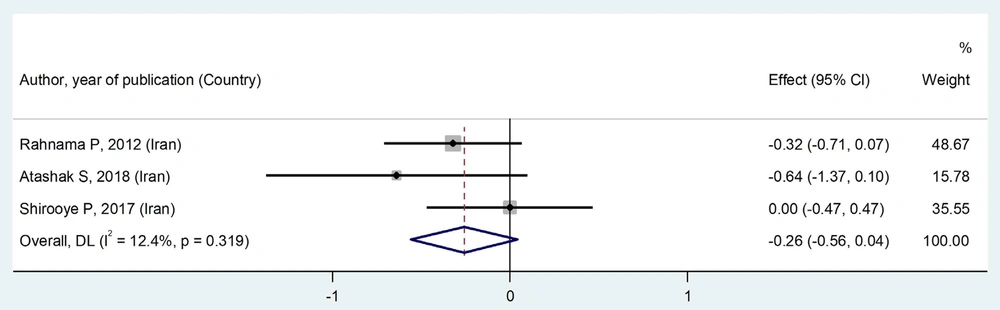

Before the intervention, the ginger and comparison groups did not differ in terms of pain duration [SMD = -0.08 (95% CI: -0.36, 0.19), P = 0.595]. After the intervention, pain duration in the ginger and comparison groups did not differ [SMD = -0.26 (95% CI: -0.56, 0.04), P = 0.319] (Figure 3).

4.2. Effect of Fennel on Primary Dysmenorrhea

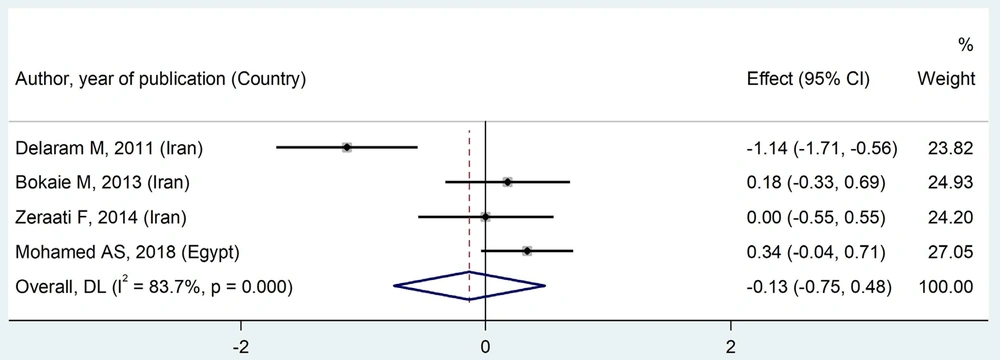

The fennel and comparison groups had no significant difference in terms of pain intensity before the intervention [SMD = -0.08 (95% CI: -0.31, 0.16), P = 0.722]. After the intervention, the pain intensity in the fennel group was not significantly different from that in the comparison group [SMD = -0.13 (95% CI: -0.75, 0.48), P = 0.000] (Figure 4). The pain duration was not evaluated in the assessed studies.

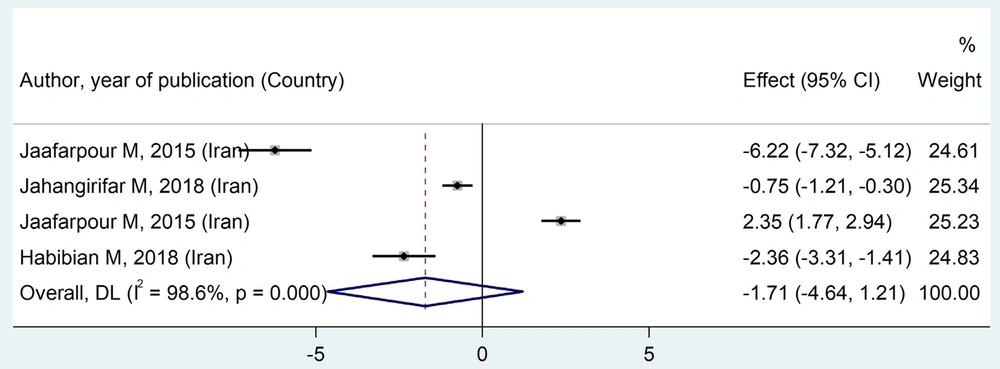

4.3. Effect of Cinnamon on Primary Dysmenorrhea

In the comparison of pain intensity, there was no significant difference between the two groups (cinnamon and comparison) before the intervention [SMD = -0.05 (95% CI: -0.36, 0.25), P = 0.205]. After the intervention, there was no statistically significant difference between the cinnamon and comparison groups in terms of pain intensity [SMD = -1.71 (95% CI: -4.64, 1.21), P < 0.001] (Figure 5).

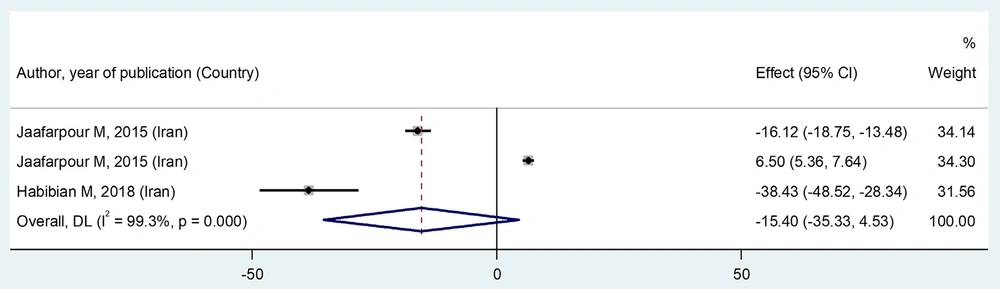

Before the intervention, the cinnamon and comparison groups did not differ in terms of pain duration [SMD = 1.58 (95% CI: -0.04, 3.21), P < 0.001]. After the intervention, no significant difference was observed between the cinnamon and comparison groups regarding pain duration [SMD = -15.40 (95% CI: -35.33, 4.53), P < 0.001] (Figure 6).

4.4. Analysis of Subgroups

In some subgroups, cinnamon (pain severity with doses of 500 mg and 1000 mg, quasi-experimental studies, compared to exercise and ibuprofen groups) and duration of pain (dose of 500 mg, clinical trial studies, and quasi-experimental studies), and ginger (pain severity with doses of 250 mg and 1000 mg, clinical trial studies, compared to placebo group) and duration of pain (compared to placebo group) were found to exert statistically positive and significant effects on the intensity and duration of pain (Table 3).

| Subgroups | SMD (95% CI) | P-Value | I2% | Significance |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Effect of ginger on pain severity | ||||

| Dose of ginger | ||||

| 200 mg | -0.59 (-1.73, 0.55) | 0.002 | 89.5 | Not significant |

| 250 mg | -1.17 (-2.22, -0.12) | < 0.001 | 92.8 | Significant |

| 500 mg | -0.99 (-2.56, 0.59) | < 0.001 | 97.1 | Not significant |

| 1000 mg | -1.53 (-1.98, -1.09) | - | 0 | Significant |

| Type of study | ||||

| Clinical trial | -1.23 (-1.93, -0.53) | < 0.001 | 94.5 | Significant |

| Quasi-experimental | -0.22 (-1.27, 0.82) | 0.018 | 82.2 | Not significant |

| Compare group | ||||

| Novafen | -0.05 (-0.35, 0.25) | - | 100 | Not significant |

| Exercise | -0.45 (-1.91, 1) | < 0.001 | 92 | Not significant |

| Placebo | -1.56 (-2.27, -0.84) | < 0.001 | 91.3 | Significant |

| Topical ginger | -0.12 (-0.59, 0.35) | - | 100 | Not significant |

| Effect of ginger on duration of pain | ||||

| Dose of ginger | ||||

| 250 mg | -0.25 (-0.86, 0.36) | 0.152 | 51.2 | Not significant |

| 500 mg | -0.32 (-0.71, 0.07) | - | 0 | Not significant |

| Type of study | ||||

| Clinical trial | -0.19 (-0.50, 0.12) | 0.301 | 6.4 | Not significant |

| Quasi-experimental | -0.64 (-1.37, 0.10) | - | 0 | Not significant |

| Compare group | ||||

| Placebo | -0.39 (-0.73, -0.05) | 0.457 | 0 | Significant |

| Effect of fennel on pain severity | ||||

| Dose of fennel | ||||

| 25 drops | 0.18 (-0.33, 0.69) | - | 100 | Not significant |

| 30 drops | -0.56 (-1.68, 0.55) | 0.005 | 87.1 | Not significant |

| One cup | 0.34 (-0.04, 0.71) | - | 0 | Not significant |

| Effect of cinnamon on pain severity | ||||

| Dose of cinnamon | ||||

| 420 mg | -1.92 (-10.33, 6.48) | < 0.001 | 99.5 | Not significant |

| 500 mg | -2.36 (-3.31, -1.41) | - | 0 | Significant |

| 1000 mg | -0.75 (-1.21, -0.30) | - | 0 | Significant |

| Type of study | ||||

| Clinical trial | 0.79 (-2.25, 3.84) | < 0.001 | 98.5 | Not significant |

| Quasi-experimental | -4.28 (-8.07, -0.49) | < 0.001 | 96.3 | Significant |

| Compare group | ||||

| Placebo | -3.46 (-8.82, 1.89) | < 0.001 | 98.8 | Not significant |

| Exercise | -2.36 (-3.31, -1.41) | - | 0 | Significant |

| Ibuprofen | 2.35 (1.77, 2.94) | - | 0 | Significant |

| Effect of cinnamon on duration of pain | ||||

| Dose of cinnamon | ||||

| 420 mg | -4.78 (26.94, 17.39) | < 0.001 | 99.6 | Not significant |

| 500 mg | -38.43 (-48.52, -28.34) | - | 0 | Significant |

| Type of study | ||||

| Clinical trial | 6.50 (5.36, 7.64) | - | 0 | Significant |

| Quasi-experimental | -26.72 (-48.55, -4.88) | < 0.001 | 94.3 | Significant |

Abbreviation: SMD, standardized mean difference.

Publication bias diagrams were drawn for each product. All three diagrams (for cinnamon, P = 0.391; for fennel, P = 0.281; and for ginger, P = 0.117) showed that there was no publication bias.

5. Discussion

Due to the contradictory results of previously published studies and considering the limitations of previous meta-analyses, the current study was conducted using a systematic review and meta-analysis method to compare the effects of the three plants (cinnamon, fennel, and ginger) and provide an overall and up-to-date result. According to the results of this study, compared to the comparison group, ginger consumption reduced the intensity and duration of pain due to PD compared to the placebo group. Since in some of the assessed studies, the routine treatment of menstrual pain control was used in the comparison group, the findings of the meta-analysis conducted by Daily et al. (41) showed that ginger has a significant effect on the reduction of VAS in women with PD. In a meta-analysis conducted by Chen et al. (42) to investigate the impact of oral ginger on dysmenorrhea, ginger was more effective in the reduction of pain intensity than placebo. The findings of these researches are consistent with the findings of the present meta-analysis, emphasizing the effectiveness of ginger consumption in improving pain from PD.

In a meta-analysis conducted by Negi et al. (43), which evaluated the impact of ginger on the treatment of PD, ginger appeared to be more beneficial for reducing menstrual pain compared to placebo. No significant difference between ginger and placebo was observed in reducing pain duration among women with early dysmenorrhea (43). Nonetheless, in the current study, ginger reduced pain duration compared to placebo. This discrepancy in results can be attributed to differences in the number of studies examined in these two meta-analyses.

Cinnamon with a dose of ≥ 500 mg was effective in reducing the intensity and duration of pain caused by PD compared to the comparison group. Habibian and Safarzadeh showed that non-pharmacological interventions such as walking with stretching exercises, cinnamon consumption, and combined intervention can reduce the severity and duration of dysmenorrhea pain in inactive girls (25). In the study by Jahangirifar et al., the results showed the mean intensity of dysmenorrhea significantly decreased over time in both groups, with a significantly greater reduction in the intervention group. Also, the pain reduction in the intervention group was significantly lower than in the placebo group after the treatment (24). The results of the above studies were consistent with the results of the current study and showed that cinnamon is an effective spice in relieving pain caused by PD.

Nevertheless, compared to the comparison group, fennel had no effect on the reduction of dysmenorrhea pain in any of the examined doses. Of course, since the comparison group included subjects who had taken painkillers or exercised and walked, the non-significant difference between the experimental and comparison groups in some of the investigated phases was expected.

In the meta-analysis carried out by Salehi et al. (44), which aimed to assess the effect of fennel on PD, the results pointed to the desirable effects of fennel on PD (44). In their meta-analysis, Lee et al. (45) evaluated the impact and safety of fennel in the reduction of pain in PD. The results of the stated study demonstrated that the influence of fennel is similar to that of common drug treatments in reducing pain. Compared to placebo, fennel had favorable effects in the reduction of pain from PD (45). The results of a meta-analysis by Shahrahmani et al. (46), which investigated fennel's impact on PD pain in comparison to NSAIDs like mefenamic acid, pinpointed that the consumption of fennel significantly reduced dysmenorrhea severity in comparison to a placebo (46). The findings of the aforementioned research were inconsistent with those obtained in the present study. This discrepancy in results can be ascribed to different pain measurement tools and pain rating indices.

5.1. Conclusions

As evidenced by the obtained results, ginger can reduce the intensity and duration of the pain caused by PD compared to the placebo group. In addition, it appears that high-dose (dose ≥ 500 mg) cinnamon consumption can be effective in reducing the severity and duration of pain in women with PD compared to the comparison group. It is recommended that more original research studies be conducted in this field, as the number of studies on each of these three plants was limited. It is also recommended that in future studies, the results of examining the effects of each of the three plants (ginger, cinnamon, and fennel) be reported in more detail. This should be done in such a way that the results are presented separately based on variables such as duration of use, form of use, dosage, etc., to provide us with more accurate results.

5.2. Limitations

There was a limited number of studies in the fennel and cinnamon groups, and it is recommended to conduct more studies in this field. Some studies' full texts were unavailable. Because there was so little evaluated research and the diverse age group of patients, it was not possible to evaluate the effect of herbal medicines (ginger, fennel, and cinnamon) separated by age group. The studies reviewed did not mention the form and method of consuming medicinal plants. The strength of this study was the comparison of the effects of three herbs (ginger, fennel, and cinnamon) in reducing pain and the duration of pain caused by PD.