1. Background

Old age may be associated with a steady rise in blood pressure (1). A progressive rise in blood pressure is not a normal physiological process but rather the result of arterial stiffening and changes in arterial compliance caused by our environment and lifestyle (2). To prevent organ damage caused by high blood pressure, patients must follow a lifelong treatment plan that includes lifestyle adjustments and blood pressure-lowering drugs. However, poor drug adherence is acknowledged as a primary factor limiting the advantages of hypertension therapy for people of all ages (3). Poor adherence to medication is associated with high morbidity and mortality and high healthcare costs (4). Many elderly patients believe that medications do not help them, do not change their disease outcomes, and may even worsen their disease status (5). For this reason, many elderly patients decide to consciously discontinue their treatment process and not take their medications (6). Many patients with chronic diseases do not adhere to their medication regimen due to fatigue caused by long-term treatments and disappointment in a definitive cure. Although elderly people usually have higher medication adherence compared to younger people (7), they often may have problems such as motor, cognitive, and memory deficits that can lead to difficulties in their care process (8). Polypharmacy, the complexity of medication regimens, the occurrence of adverse drug reactions, cultural aspects, and difficulties in accessing medications due to high cost can affect the level of medication adherence in older people (9). Patients are often worried about their future and may suffer from depression and hopelessness. In this regard, hope is a factor that can protect people from stressful life events (10). Hope may lead to setting meaningful goals as well as meaningful spiritual experiences, thereby increasing meaning in life and ultimately well-being (11).

Hope can be defined as a purposeful thought that allows individuals to identify paths to achieve their goals (12). Hope reflects individuals’ perception of their abilities to achieve goals and develop ways to achieve them (13). Therefore, hope is considered an effective factor in coping with chronic diseases (14). Hope helps patients to endure the crisis of illness (15). Hope is positively associated with healthy behaviors in older adults (16). Evidence has shown that there is a relationship between spiritual well-being and hope. In societies with rich cultural and religious beliefs, the positive relationship between spiritual health and hope means that patients feel the presence of God in their lives (17). The relationship between meaning in life and hope is defined as purposeful thinking towards a desirable future. A sense of meaning in life strengthens hope and leads to the individual maintaining hope even in adverse situations (18). Meaning in life is one of the important factors against the feeling of hopelessness in life and is realized through the fulfillment of basic needs towards purposefulness and self-worth. The lack of meaning makes a person feel hopeless, empty, and bored (19). Both meaning in life and hope are purposeful and future-oriented. Purpose is the main aspect of the meaning of life, and hope is guided by these meaningful goals (19). Therefore, one of the important future-oriented functions of meaning in life is to promote a sense of hope (12). However, a study conducted among Iranian elderly people with chronic diseases showed that there was no significant relationship between hope and treatment adherence (20). In another study conducted among patients with schizophrenia, no relationship was seen between hope and treatment adherence (21).

Given the country's growing older population in the coming years, proper and principled planning for common chronic diseases and disorders in this group should be implemented to detect key health problems among the elderly. Medication adherence is one of the most critical medical issues in geriatric nursing because if senior patients with chronic diseases do not take their medication, the disease will worsen and the rate of hospitalization will rise. Despite significant breakthroughs in hypertension treatment, many people, particularly the elderly, continue to suffer from fatal repercussions as a result of uncontrolled high blood pressure. Hope and meaning in life are concepts that can directly or indirectly affect people's health behaviors. In the elderly, a sense of hope and meaning in life can act as a source of motivation to maintain health and adhere to medication. Elderly people who have hope for the future and a sense of meaning in life will be more willing to take care of themselves and follow medical recommendations. Therefore, the relationship of these concepts with medication adherence can be effective in improving hypertension control. Understanding the relationship between hope, meaning in life, and medication adherence can help design and implement effective psychological and health interventions. If research shows that hope and meaning in life facilitate improved medication adherence, this information could be used to design educational and support programs for older adults that focus not only on medication adherence but also on improving their mental health.

2. Objectives

The aim of this study was to investigate the relationship between hope and meaning in life and medication adherence in older adults with hypertension.

3. Methods

The present study is a cross-sectional descriptive-correlational study, conducted after approval by the Ethics Committee of Mazandaran University of Medical Sciences with the ethics code IR.MAZUMS.REC.1402.574, on 200 elderly people aged 60 and older with hypertension from February 1402 to May 1403 in seven health centers in Mahmoudabad city.

The sampling method in this study was a multi-stage cluster sampling with proportional quota allocation and random selection within clusters, chosen to balance feasibility and representativeness given the dispersed population and resource constraints. Specifically, two centers were selected from two urban health centers, and five centers were randomly selected. The number of samples required from each center was determined as a quota proportional to the number of referrals (elderly people with hypertension) to the selected urban and rural centers. Then, the samples were selected from the list of names available in the centers by generating random numbers in Excel software. After contacting the center by phone and providing the necessary information about the reason for the study, the individuals agreed to participate in the study. Following the presence of the samples at the sampling centers and obtaining written informed consent from the elderly, the sampling process and completion of the questionnaires by the researcher began through an interview method. Based on a pilot study with 25 participants, the required sample size was determined. The number of samples was calculated at a confidence level of 95% and a power of 95%. Based on the correlation between the meaning of life and medication adherence (R = 0.266), which was the lowest correlation between the variables, the sample size was calculated to be at least 178 people. Considering about 10% attrition due to non-response and incomplete completion of the questionnaires, 198 samples were needed. Finally, 200 people were selected for the study.

To collect data from the centers, 21 samples from Ahmadabad centers, 17 samples from Ahlam, 35 samples from Mateverij, 29 samples from Galeshpol, 26 samples from Moalem Kola, 16 samples from Shahid Nategh Nouri, and 56 samples from Shohadaye 7 Tir were selected. The inclusion criteria for the study included: Being 60 years old and older, residing in Mahmoudabad city, having high blood pressure confirmed by a specialist physician, having been diagnosed with the disease for at least four months, not having experienced stressful events in the past six months such as the death of loved ones and divorce, not having cognitive problems with a score of 7 or higher on the abbreviated mental test (AMT), being able to communicate (in terms of hearing, vision, and dialect), and having a score of 6 (full score) on the Katz Index of Independence in Activities of Daily Living (ADL) test. The exclusion criteria included withdrawing from the study and incomplete completion of the questionnaires. Data collection tools included: Demographic-Medical Information Questionnaire [age, gender, education, income, occupation, life partners, Body Mass Index (BMI), place of residence], AMT, Katz Index of Independence in ADL, Snyder Hope Questionnaire (SHQ), Meaning in Life Questionnaire (MLQ), and Morisky Medication Adherence Questionnaire.

3.1. Abbreviated Mental Test

One of the tools used in this study is the AMT Questionnaire. This questionnaire, with 10 questions, was first developed by Hodkinson in 1972 from the 37-question Roth-Hopkins test, and its sensitivity and specificity were determined in 1974. This tool has a high speed of cognitive assessment in illiterate elderly patients. The ideal cut-off point is 7. The translation of the instrument, its validity, and reliability in Iran were carried out by Bakhtiyari et al. (22). The sensitivity of the instrument was determined to be 85%, and its specificity was determined to be 99%. The internal consistency of the questionnaire, measured by Cronbach's alpha, was 0.76. The external reliability, assessed by the intergroup correlation coefficient, was 0.89. The discriminant validity for distinguishing between individuals without cognitive impairment and those with cognitive impairment was satisfactory, with values of 7.35 and 5.96, respectively (23). The samples of this study were included in the study after obtaining a score of 7 and above.

3.2. Activities of Daily Living

Katz's ADL Questionnaire had six items, including bathing, dressing, going to the toilet, moving around the house, controlling urination and defecation, and eating. Each question has 1 point, and a total of 6 points, with a higher score indicating greater independence. Habibi Sola et al. reported the reliability of the instrument using the test-retest method (0.9) (24). The content validity of the instrument was 82.0, and its reliability was determined by Cronbach's alpha and internal correlation of both 0.750. In addition, the sensitivity and specificity of the instrument were 0.750 and 0.960, respectively, in 2015 by Taheri Tanjani and Azadbakht (25).

3.3. Snyder’s Hope Scale

The Hope Questionnaire consists of 12 questions that were designed and prepared by Snyder et al. (26). The purpose of this questionnaire is to assess the level of hope in individuals. This questionnaire measures two subscales: Agency and pathways (planning to meet goals). Its scoring method is based on a 5-point Likert scale, ranging from strongly disagree with a score of 1 to strongly agree with a score of 5 (27). Questions 3, 7, and 11 are inverted. Higher scores indicate greater hope in the respondent and vice versa (26). Questions 1, 4, 6, and 8 are related to the agency thinking subscale, and questions 2, 9, 10, and 12 are related to the pathways thinking subscale. The hope score is the sum of these two subscales. Higher scores indicate a higher level of hope in the respondent and vice versa (28). The reliability of the questionnaire was examined by Ghaniei et al. and confirmed with an alpha coefficient of 0.9 (13). This questionnaire was examined in Iranian elderly people by Oraki et al. using the internal consistency method and confirmed with an alpha coefficient of 0.91 (28). The concurrent validity of the scale with the optimism, goal achievement expectation, and self-esteem scales was estimated to be between 0.50 and 0.60 (29). The reliability of the questionnaire in the present study was calculated based on Cronbach's alpha coefficient of 0.847.

3.4. Meaning in Life Questionnaire

Steger et al. developed the MLQ in 2006. It was designed to assess the existence of meaning and the effort required to find it, and the instrument's validity, reliability, and factor structure were investigated in various studies with different samples. The researchers initially created 44 items to build the instrument and then used exploratory factor analysis to identify two factors: Meaning in life and search for meaning in life, totaling 17 items. Subsequently, using confirmatory factor analysis, they obtained an appropriate two-factor structure with ten items after removing seven. The questionnaire is scored from 1 (completely incorrect) to 7 (completely correct). In this test, question 9 is scored in reverse (30). Items 1, 4, 5, 6, and 9 are assigned to the presence subscale, while items 2, 3, 7, 8, and 10 are assigned to the search subscale. A score of more than 24 in the presence dimension and more than 24 in the search for meaning dimension indicates an individual who feels that his or her life has a meaningful and valuable purpose (31). According to research by Steger et al., the validity of the meaning in life subscale was 0.86, and the search for meaning subscale was 0.87, with their reliability estimated to be 0.70 and 0.73, respectively (30). The reliability and validity of this questionnaire were confirmed by Abedi et al. through a Cronbach's alpha of 0.85 and a test-retest reliability of 0.81 (32). In the present study, the reliability of this questionnaire was calculated based on a Cronbach's alpha of 0.949.

3.5. MMAS

This questionnaire was designed by Morisky et al. in 2008 to assess medication adherence. This scale is used in a variety of chronic patients and includes 8 questions. The first seven questions are answered with yes or no and scored as 0 and 1, while the last question, which is the eighth question, is scored on a 5-point Likert scale (never, rarely, sometimes, most of the time, and always) and scored as 0, 0.25, 0.5, 0.75, and 1. Question 5 is scored in the opposite way to the other items. The overall range of scores on this scale is between 0 and 8, with a score of 8 indicating high adherence to medication, scores of 6 and 7 indicating moderate adherence, and a score of less than 6 indicating poor adherence (33). The authors translated the Morisky Scale into Persian, and its reliability has been confirmed (R = 0.8 and Cronbach's alpha 0.7) (34). Moharramzad et al. also translated this tool into Persian and confirmed the reliability of the Persian version. In this study, Cronbach's alpha was 0.697 (35). The reliability of the questionnaire in the present study was calculated based on a Cronbach's alpha coefficient of 0.694.

3.6. Data Analysis

Data analysis was performed using SPSS software version 26 at a significance level of 0.05. Qualitative variables were reported with frequency and percentage, and quantitative variables with mean (standard deviation). The normality of the medication adherence variable was examined using the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test, skewness, and kurtosis. The results indicated severe skewness (-2.05) and kurtosis (5.88), leading to the rejection of the normality assumption. Given the lack of normality assumption for medication adherence, analyses were performed using nonparametric tests. Comparison of medication adherence in groups was performed using Mann-Whitney and Kruskal-Wallis tests, and the correlation of variables was examined based on Spearman's correlation test. To investigate the association between hope and meaning in life with medication adherence while controlling for demographic and socioeconomic variables, generalized linear models (GLMs) were employed. Initially, each variable was entered into the model separately. Subsequently, variables with a P-value less than 0.3 were included in a multiple model to examine their concurrent relationship with medication adherence.

4. Results

According to the study's findings, married people had a higher average medication adherence score than others, and elderly people with higher incomes had a higher medication adherence score. When medication adherence scores were compared by life partner, the average medication adherence score in elderly people living with their children was significantly lower than in other people (Table 1).

| Variables | Mean ± Standard Deviation | P-Value |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | 0.444 | |

| Female | 6.47 ± 1.46 | |

| Male | 6.26 ± 1.62 | |

| Marital status | 0.023 | |

| Married | 6.5 ± 1.49 | |

| Single, widow, and divorced | 5.98 ± 1.58 | |

| Education | 0.058 | |

| Illiterate | 6.23 ± 1.53 | |

| Below diploma | 6.3 ± 1.59 | |

| Diploma or higher | 6.83 ± 1.3 | |

| Employment status | 0.215 | |

| Employed | 6.19 ± 1.61 | |

| Housewife | 6.34 ± 1.47 | |

| Unemployed | 6.65 ± 1.56 | |

| Location | 0.423 | |

| City | 6.49 ± 1.42 | |

| Village | 6.32 ± 1.58 | |

| Life companions | 0.011 | |

| Alone | 6.14 ± 1.66 | |

| Spouse | 6.52 ± 1.49 | |

| Children | 5.59 ± 1.39 | |

| Income | 0.001 | |

| Less than cost | 5.8 ± 1.51 | |

| Equal to cost | 6.48 ± 1.48 | |

| More than cost | 6.97 ± 1.48 | |

| Underlying diseases | 0.051 | |

| No | 6.22 ± 1.55 | |

| Yes | 6.61 ± 1.46 |

The relationship between the variables under study and medication adherence is shown in Table 2: According to the results of the univariate model, lower income was associated with lower chances of medication adherence. In contrast, people who lived with their spouses had higher medication adherence than those who lived with their children without spouses. Additionally, people with higher hope and greater meaning in life had higher medication adherence both in general and in all its dimensions. In the multiple model, after controlling for other factors, only the variables of hope and meaning in life had a significant relationship with medication adherence. Specifically, for each higher hope score [odds ratio (OR) = 1.01, P = 0.049] and each higher meaning of life score (OR = 1.01, P < 0.001), the chance of medication adherence was one percent higher.

| Variables | Univariate Models | Multiple Models | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR | 95% Confidence Interval | P-Value | OR | 95% Confidence Interval | P-Value | |

| Gender | ||||||

| Female | 1.03 | (0.96, 1.12) | 0.410 | - | - | - |

| Male a | 1.00 | - | - | - | - | - |

| Marital status | ||||||

| Married | 1.09 | (0.99, 1.19) | 0.071 | 1.07 | (0.88, 1.3) | 0.252 |

| Other a | 1.00 | - | - | - | - | - |

| Employment status | ||||||

| Employed | 0.93 | (0.83, 1.04) | 0.215 | 0.91 | (0.82, 1.01) | 0.064 |

| Housewife | 0.95 | (0.87, 1.05) | 0.326 | 1.02 | (0.92, 1.13) | 0.696 |

| Unemployed a | 1.00 | - | - | - | - | - |

| Income | ||||||

| Less than cost | 0.83 | (0.73, 0.95) | 0.007 | 0.99 | (0.86, 1.14) | 0.895 |

| Equal to cost | 0.93 | (0.83, 1.04) | 0.216 | 1.03 | (0.92, 1.14) | 0.622 |

| More than cost a | 1.00 | - | - | - | - | - |

| Location | ||||||

| City | 1.03 | (0.95, 1.11) | 0.507 | - | - | - |

| Village a | 1.00 | - | - | - | - | - |

| Life companions | ||||||

| Alone | 1.10 | (0.93, 1.29) | 0.257 | 1.07 | (0.93, 1.23) | 0.380 |

| Spouse | 1.17 | (1.02, 1.33) | 0.024 | 0.94 | (0.75, 1.19) | 0.623 |

| Children a | 1.00 | - | - | - | - | - |

| Underlying diseases | ||||||

| No | 0.94 | (0.87, 1.02) | 0.127 | 0.95 | (0.89, 1.01) | 0.123 |

| Yes a | 1.00 | - | - | - | - | - |

| Education | ||||||

| Illiterate | 0.91 | (0.82, 1.01) | 0.086 | 1.01 | (0.9, 1.13) | 0.933 |

| Below diploma | 0.92 | (0.83, 1.02) | 0.116 | 1.00 | (0.91, 1.11) | 0.941 |

| Diploma or higher a | 1.00 | - | - | - | - | - |

| Age (on a 10-year scale) | 0.964 | (0.91, 1.02) | 0.190 | 1.00 | (0.95,1.06) | 0.957 |

| BMI | 1.001 | (0.99, 1.01) | 0.894 | - | - | - |

| Hope-factory thinking | 1.048 | (1.04, 1.06) | < 0.001 | - | - | - |

| Hope-strategic thinking | 1.039 | (1.03, 1.05) | < 0.001 | - | - | - |

| Hope | 1.025 | (1.02, 1.03) | < 0.001 | 1.01 | (1,1.02) | 0.049 |

| The meaning of life: Existence | 1.038 | (1.03, 1.05) | < 0.001 | - | - | - |

| The meaning of life: Search | 1.026 | (1.02, 1.03) | < 0.001 | - | - | - |

| The meaning of life | 1.017 | (1.01, 1.02) | < 0.001 | 1.01 | (1.01, 1.02) | < 0.001 |

Abbreviations: OR, odds ratio; BMI, Body Mass Index.

a Reference line.

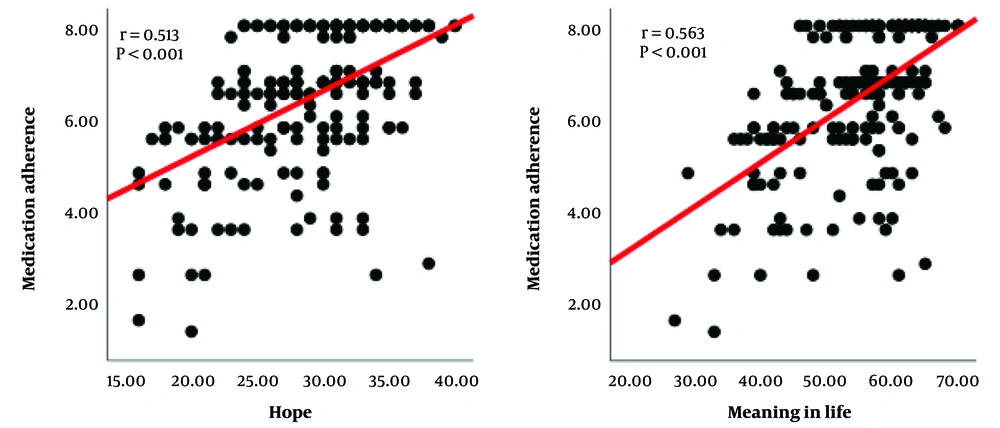

As illustrated in Figure 1, correlation analyses revealed that both hope and meaning in life were significantly associated with medication adherence. A moderate positive correlation was found between hope and adherence (R = 0.513, P < 0.001). Similarly, a statistically significant moderate correlation was observed between meaning in life and adherence, which was slightly stronger (R = 0.563, P < 0.001). These results consistently indicate that higher levels of both psychological constructs are associated with better medication adherence.

5. Discussion

The study's conclusions showed a strong correlation between medication adherence, hope, and life purpose. Higher hope and purpose in life ratings among older adults with hypertension were associated with improved adherence to their recommended medication schedules. Adherence to medication is a complicated phenomenon that is impacted by several circumstances. It is frequently believed that insufficient patient education is the primary cause of poor adherence and that closing this gap would result in a shift in patient behavior. However, even after receiving adequate instruction, some patients may not follow their treatment plans. This emphasizes the importance of considering sociocultural elements that are significant in medication adherence, such as habits, beliefs, attitudes, and other personal traits. Due to a number of factors, such as low income and educational attainment, living alone, a lack of social support from friends and family, depressive symptoms, comorbid chronic illnesses, and the need to manage several medications at once, elderly people are especially susceptible to poor medication adherence (36). Just 15.23% of the 282 participants in Zare et al.'s research on antihypertensive medication adherence among cardiac patients who visit Imam Reza Clinic in Shiraz showed moderate to high levels of adherence to their antihypertensive regimens. In the current research, 32.5% of individuals showed strong medication adherence. In line with Zare et al.'s research, the study likewise revealed no significant correlation between adherence and either gender or educational attainment. In contrast to Zare et al.'s findings, the current investigation found a substantial correlation between adherence and married status (37). It is important to note that whereas the participants in the current study were solely senior people 60 years of age and above, Zare et al.'s study included people between the ages of 35 and 70. According to Epakchipoor et al.’s study, medication adherence was statistically correlated with occupation, financial adequacy, job status, and educational attainment, and it was substantially lower in males than in females. Regarding the connection between medication adherence and income, the results of the new study agreed with those of the previous study. Comparing the results to other factors, however, revealed differences (38). In contrast to the results of this study, a substantial correlation between medication adherence, age, and education was found in the study by Gholamaliei et al. (39). Only 35% of the sample in the current study lacked literacy, compared to 65% of participants in their study. The large percentage of illiterate participants in their study may be explained by the importance of education. The substantial correlation between age and medication adherence may also be explained by the fact that their study included people ranging in age from 30 to 65. Given that every person in this study was senior, this discrepancy may result from generational differences between younger and older people. In line with the findings of Pazokian et al. (40), the results of this investigation showed a direct and substantial link between hope and medication adherence. Similar to the current investigation, a study conducted on 109 individuals with schizophrenia by Kavak and Yilmaz showed a significant relationship between hope and treatment adherence (41). This difference could be due to different sampling methods and also different diseases of the individuals. In contrast to the current findings, Shareinia et al.’s findings indicated that older adults with high levels of optimism do not always adhere to their drug regimens better (42). The Morisky Medication Adherence Questionnaire was used in both trials to measure adherence. However, the current study employed Snyder's Hope Scale, while the Shareinia study used Herth's Hope Index. The Snyder Hope Scale is a combination of two subscales: Functional thinking and strategic thinking, while the Herth Hope Questionnaire is a 12-item, three-choice Likert scale. It seems that using more accurate instruments increases the likelihood of receiving more accurate and meaningful answers. The employment of different measuring instruments may be the cause of these discrepancies in the results. Higher hope scores were shown to be substantially linked to lower non-adherence to treatment in the study by Kisaoglu and Tel (43), suggesting a strong relationship between the two variables that is in line with the findings of this investigation. The findings of this study are consistent with those of Reis et al., who discovered a direct and substantial correlation between medication adherence and purpose in life (44). This difference may have been due to the different nature of the disease and the difference in the measurement tool of the Hope Questionnaire. A research by Teetharatkul and Pitanupong was titled "Good Medication Adherence and Its Association with Meaning in Life in Thai Individuals with Schizophrenia". In contrast to the current study's findings, theirs showed that individuals had strong adherence scores. Given that the subjects also reported high ratings for meaning in life, this disparity may be caused by the nature of their conditions. It's interesting to note that despite the fact that every participant showed strong medication adherence, the study found no significant correlation between adherence and life purpose (45). In contrast, the current study found a significant correlation between meaning in life and medication adherence, reinforcing the importance of this connection. Additionally, helping patients identify and create meaning and purpose in their lives can increase their motivation to adhere to treatment adherence.

5.1. Conclusions

In this study, elderly people who had higher levels of hope and meaning in life demonstrated better medication adherence. Additionally, married elderly individuals with adequate income showed higher medication adherence.

5.2. Limitations

This study has several limitations. First, relying on self-reported medication adherence among older adults may introduce recall bias and social desirability effects, affecting accuracy. This is supported by the borderline internal consistency (α = 0.694) of the Morisky Scale in our sample, a known issue in geriatric populations. Second, the cross-sectional design limits causal interpretations between hope, meaning in life, and adherence. Finally, the results may not generalize beyond the specific cultural and geographic context. Future longitudinal studies with objective adherence measures are recommended to validate these findings. Mahmoudabad County has a relatively ethnically homogeneous population, which may limit the applicability of the results to more diverse communities. Cultural and social differences across regions can influence experiences of hope, meaning, and treatment adherence. Therefore, future studies in more diverse settings are recommended.