1. Background

In healthcare organizations, human resources are among the most important organizational assets, playing a fundamental role in improving access to services and the quality of care (1, 2). Nurses constitute the largest portion of the healthcare team and account for the majority of patient care in hospitals (2). Healthcare systems worldwide face increasing demand due to population aging, the rising prevalence of chronic diseases, and the need to provide both acute and preventive services. This demand was especially pronounced during the COVID-19 pandemic, when healthcare personnel faced significant pressure from heavy workloads, staff shortages, insufficient personal protective equipment (PPE), and an increased risk of infection (3).

Nurses work in environments characterized by tension and stress, which requires particular attention. The shortage of nurses and their turnover is a global challenge affecting both developed and developing countries. To achieve effective and efficient nursing care, nurses must possess skills and expertise as well as sufficient interest, morale, and motivation. Therefore, attention to factors that can reduce job-related stress among nurses is necessary for healthcare organizations, as this can lead to increased organizational productivity, improved patient care quality, and ultimately the promotion of community health (4-6).

Studies indicate that individuals who experience less external pressure at work are happier and can be more creative in their activities. Such creativity positively affects motivation, particularly intrinsic motivation, enabling individuals to perform their jobs more creatively and with higher motivation. Conversely, individuals with greater inherent motivation experience more satisfaction and enjoyment from their work (7-9). In healthcare organizations, job motivation is a key determinant of how human resources respond to the increasing challenges and demands of the health system. Motivation is recognized as a process that begins with internal inspiration and continues until a task is completed; it can be considered the first step toward achieving goals. Motivation is a complex and multidimensional internal force that affects and directs individual behavior (10).

Job motivation is a primary tool for regulating personnel behavior (11), leading to interest, perseverance, and the desire to achieve organizational goals. Therefore, fostering motivation is one of the most important responsibilities of managers in any organization (12). Encouraging and rewarding employees to boost morale and efficiency is one way to create motivation (13).

In the nursing profession, rapid decision-making, unpredictable and high-risk situations, lack of control, organizational constraints, and critically ill patients are conditions that, without sufficient motivation, can quickly lead to fatigue, increased errors, absenteeism, or reduced quality of nursing services. Factors such as working conditions, supervision, and management style significantly affect nurses' job motivation (14). A study on nurses in Turkey indicated a moderate level of motivation (15), while several studies in African countries reported low levels of job motivation among nurses (16-18). Studies in Iran show mixed results; Hasnain et al.’s study reported high motivation (14), whereas Soltani reported moderate motivation (19). These differing results across studies and cultures indicate the need for further research.

One area that has received increasing attention is positive psychology interventions. Positive psychology, first popularized by Seligman et al., emphasizes enhancing individuals' strengths, virtues, and sense of meaning to help them succeed (20, 21). Positive psychology interventions are structured activities that promote flourishing by supporting individuals' thoughts and behaviors. This approach has been successfully used in organizations and healthcare settings. Such interventions are cost-effective and relatively easy to implement (22), and several meta-analyses indicate they are associated with increased well-being and reduced symptoms of depression (23, 24). Therefore, positive psychology methods can increase commitment and motivate individuals to pursue their lives and work with greater purpose (25). Several studies have demonstrated the utility of positive psychology in the workplace. A study in Iran investigated the effects of positive thinking on nurses' quality of working life and reported improvements (26). A study in Italy found that positive psychology interventions focusing on positive appraisals of work roles can effectively increase employee engagement (27). In the United States, positive psychology methods significantly improved job performance and job motivation among employed individuals (28). Positive psychology has attracted attention as a practical strategy for organizations seeking higher productivity and goal achievement. By increasing job well-being, these interventions can lead to greater happiness, improved employee performance, and higher motivation (29). Despite the growing evidence of positive psychology's effectiveness, a critical gap remains in the literature. The majority of existing studies have focused on general employee populations or on outcomes like engagement and well-being. Few studies, however, have specifically examined the impact of positive psychology interventions on both nurses' job performance and its constituent dimensions within the Iranian healthcare context. Given the unique, high-stress demands of nursing and the reported success of positive thinking interventions in this professional group, there is a clear, pressing need to specifically investigate the effectiveness of these methods in directly enhancing measurable job performance outcomes among nurses. Therefore, this study is justified as it aims to bridge this theoretical and practical gap by providing evidence-based insights necessary for developing targeted, effective interventions in the nursing sector.

2. Objectives

Considering that group training in positive psychology can be effective in fostering job motivation and that such interventions can serve as efficient tools to help health managers enhance system productivity, the present study was conducted to determine the effectiveness of group positive-psychology training on nurses' job motivation.

3. Methods

3.1. Research Design

The present study was a non-randomized controlled trial conducted in 2021.

3.2. Setting and Samples

The study population comprised all nurses working at Imam Reza Hospital in Kermanshah, Iran (640 individuals). The sample size was calculated using G*Power software, assuming a medium effect size (Cohen’s d = 0.5), 80% power, and alpha = 0.05, yielding a total of 64 participants (32 per group). Due to logistical constraints, a non-randomized design was used, but wards were selected to ensure similarity in workload and patient demographics. Using a coin-toss method, two similar wards were selected — one for the control group and one for the intervention group. To ensure homogeneity, nurses working in each selected ward who met the inclusion criteria were selected by simple random sampling. Specifically, personnel numbers were written on pieces of paper and placed in a box; papers were drawn one by one until the desired sample size was reached.

Inclusion criteria: Conscious and voluntary willingness to participate, at least one year of nursing experience, not using tranquilizers, no death of first-degree relatives in recent months, no specific psychiatric disorders (e.g., major depressive disorder, bipolar disorder, psychosis), and continuous internet access during synchronous virtual sessions. Exclusion criteria: Unwillingness to continue participation at any stage, participation in other counseling or psychological programs concurrently, or more than two absences from sessions.

3.3. Measurement and Data Collection

Two questionnaires were used: A Demographic Information Questionnaire (such as age, gender, level of education, organizational position, length of service, department, shift type, income, and history of divorce) and Herzberg's Job Motivation Questionnaire. Herzberg's Questionnaire contains 40 items and is based on Herzberg's two-factor theory, covering intrinsic and extrinsic motivation factors. The questionnaire measures 11 components: Five intrinsic factors — recognition and appreciation (5 items, score range 5 - 25), career advancement and development (4 items, score range 4 - 20), nature of work (3 items, score range 3 - 15), independence and responsibility (3 items, score range 3 - 15), and success and promotion (2 items, score range 2 - 10); and six extrinsic (hygiene) factors — salary and wages (3 items, score range 3 - 15), workplace policies (3 items, score range 3 - 15), relationships with others (5 items, score range 5 - 25), job security (4 items, score range 4 - 20), work environment conditions (3 items, score range 3 - 15), and supervision by superiors (5 items, score range 5 - 25). Items are scored on a five-point Likert scale from 1 (unimportant) to 5 (very important) (30, 31). Overall, total scores range from 40 to 200, with higher scores indicating better motivation (32).

A panel of Iranian nursing experts reviewed the Herzberg Questionnaire to ensure cultural relevance, with minor wording adjustments to reflect local workplace norms (14, 33). Its validity and reliability have been confirmed in a study by Hasanain et al., in which Cronbach's alpha was 0.97 (14). In the present study, reliability was assessed using a test-retest method over a two-week interval in a pilot sample of 15 randomly selected nurses; the internal reliability (Cronbach's alpha) was 0.89.

To prevent contamination of information between intervention and control groups, demographic and Job Motivation questionnaires were initially sent by email to the nurses in the control group, and two weeks were allowed for completion (34). Reminder emails were sent during this period. After completing sampling in the control group, information from the intervention group was collected.

Due to the COVID-19 pandemic, sessions were held using a combination of in-person and virtual (synchronous and asynchronous) formats. For the intervention group, seven weekly 120-minute sessions on positive psychology, based on Seligman and Rashid's protocol, were delivered by a member of the research team who holds a PhD in psychology and has completed a certified training course in Seligman’s positive psychology interventions. For content validity, the educational materials were reviewed and approved by 10 professors of psychology and nursing from Tehran and Kermanshah University of Medical Sciences.

3.4. Intervention

As Table 1 shows, Sessions 1 and 2 introduced strengths-based storytelling and fostered self-awareness using positive psychology principles. Sessions 3 and 4 emphasized optimism, hope, and meaning-making amid challenges. Session 5 targeted psychological capital by bolstering self-efficacy, resilience, and motivation linked to positive interpersonal relations. Session 6 enhanced group cohesion and social support through shared narratives and emotional reflection. Session 7 consolidated the intervention, enabling participants to reflect on personal growth, apply strengths in service to others, and sustain a positive outlook beyond the program.

| Sessions | Learning Objectives | Teaching and Learning Methods | Theoretical Framework |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Orient participants to the framework of positive psychotherapy; clarifying roles and expectations; initiating positive self-narratives | Lecture and group discussion supported by PowerPoint; participants write a “Positive Self-Introduction” story, describing a time when they felt at their best. | Positive psychotherapy; character strengths framework (21); strength-based narrative |

| 2 | Sharing personal stories; exploring participants’ worldview toward nursing; identifying and activating personal strengths; assigning a strengths-based action plan | Story-sharing; guided discussion on job-related beliefs, positive/negative memories, and strength-based reflection; preparation of a “Name Your Strengths” plan exercise | Cognitive reframing, strengths activation, self-reflection, and positive psychology |

| 3 | Building understanding of optimism and hope; facilitating peer discussion to enrich personal experiences of positive future thinking | Slide presentation with PDFs and video/audio resources; group discussion on hope and optimism in relation to well-being | Learned optimism (35); attributional style theory; hope theory; positive psychotherapy |

| 4 | Emphasizing purposeful goal focus, acceptance of challenges, and meaning-making in professional life | Multimedia session with slides, PDFs, and group dialogue; exercises exploring coping with problems, focusing on goals, and deriving meaning | Acceptance and meaning in positive psychotherapy; emotional regulation; mindful acceptance of negative experiences alongside positive ones |

| 5 | Linking optimism and hope to work motivation; promotion of responsibility, positive relationships, and psychological capital | PowerPoint and multimedia presentation; hot-seat peer feedback activity in which participants accept responsibility statements and exchange positive observations | Psychological capital framework (self-efficacy, hope, resilience, optimism); positive interpersonal feedback; positive workplace relationships |

| 6 | Cultivating shared positive memories; strengthening interpersonal connections; challenging unhelpful thoughts; boosting relational confidence | Group storytelling of positive shared experiences; reflection exercises; strategies for building positive social bonds and reframing negative thoughts | Narratives for self-esteem; social support theory; empowerment through storytelling; positive emotion and resilience |

| 7 | Consolidation of therapeutic gains; integration of positive psychotherapy content; encouraging expression of feelings and motivation to serve others meaningfully | Final group discussion and wrap-up; sharing task outcomes; emotional/cognitive feedback; planning for continued use of strengths in meaningful roles | Meaning-making in life, sustained positive behavior, therapeutic closure, and post-intervention integration of strengths |

Except for the first session, which was held in person to familiarize participants with the intervention at the hospital, the remaining sessions were held virtually both synchronously and asynchronously due to the COVID-19 pandemic and the nurses' heavy workload. The second and seventh sessions were conducted online with all intervention-group members via the Sky Room platform, featuring lectures by the instructor, question-and-answer sessions, and session assignments. These sessions introduced positive psychology, facilitated participant introductions, and familiarized attendees with their strengths, worldview, and the role of positive thinking in hope and optimism.

Sessions 3 to 6 were delivered virtually and asynchronously on Telegram through questions and answers (Q&A) and posted audio files. These sessions continued discussions on hope and optimism, goal setting and meaning-making, empowerment, understanding motivation, and fostering interpersonal enjoyment. Each session included homework assignments relevant to the topic. For synchronous virtual sessions, all participants and the research team logged in at scheduled times. The research team conducted sessions using audio-visual presentations (slides, PDF files) and specific session programs. Group discussions and Q&A were conducted through audio-visual and written materials. Throughout the study, the research team was available to answer participants' questions privately or in the virtual group. Assignments were submitted confidentially to the research team and discussed anonymously in virtual sessions. All sessions were scheduled in advance and required simultaneous online presence (36-39).

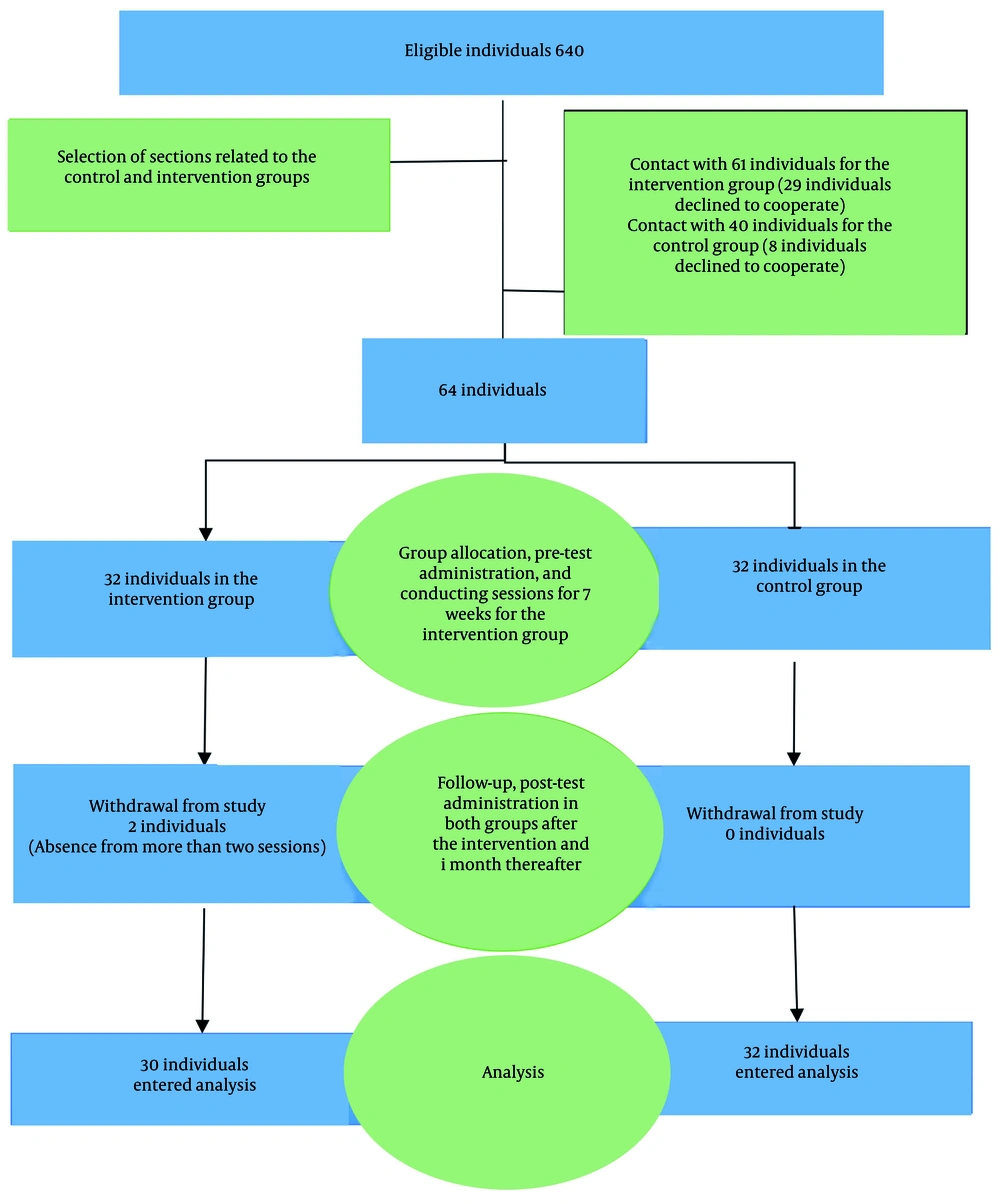

After completing the sessions, the Job Motivation Questionnaire was emailed to participants immediately and one month after the end of training to conduct post-tests and determine the persistence of the intervention's effectiveness (40, 41). Participants were given one week to complete the questionnaire, and reminder emails were sent. No intervention was provided for the control group. Two individuals from the intervention group dropped out due to more than two absences (Figure 1).

3.5. Data Analysis

The collected data were analyzed using SPSS version 21. Independent t-tests, Pearson correlation, analysis of variance (ANOVA), chi-square test, Mann-Whitney U test, and Kruskal-Wallis test were employed as appropriate. Chi-square and Fisher's exact tests examined the homogeneity of qualitative variables between the two groups; independent t-tests compared quantitative variables. Repeated-measures ANOVA was used to compare job motivation before, immediately after, and one month after the intervention. A per-protocol approach was used for data analysis. Data analysts were blinded to group assignments to minimize bias. None of the demographic variables had a statistically significant difference between the two groups, so no confounder was identified.

3.6. Ethical Considerations

Ethics approval was obtained from the Research Ethics Committee of Tehran University of Medical Sciences (IR.TUMS.FNM.REC.1399.131), and the trial was registered (IRCT20210228050529N1). All participants provided written informed consent after being informed of the study’s purpose, potential benefits (such as improved motivation), risks (such as time commitment), and their right to withdraw at any time. The questionnaires were completed anonymously using unique participant IDs. Participation was voluntary, and participants were informed of their right to withdraw at any time without consequences. All data were kept confidential and anonymized, used solely for research purposes, and stored securely in compliance with ethical standards.

4. Results

Figure 1 illustrates the study flow according to CONSORT criteria, detailing participant recruitment, allocation, and follow-up. Nurses in the intervention and control groups were compared based on individual and occupational characteristics (Table 2). The two groups did not show statistically significant differences and were homogeneous in terms of gender, education level, organizational position, employment type, shift type, department of service, marital status, history of divorce, income level, caring for COVID-19 patients, history of COVID-19 infection, age, and years of service (P ≤ 0.05).

| Individual and Occupational Characteristics | Intervention Group (n = 30) | Control Group (n = 32) | Test Result (P) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | 0.472 b | ||

| Female | 18 (60) | 22 (68.8) | |

| Male | 12 (40) | 10 (31.3) | |

| Education | 0.709 c | ||

| Bachelor's | 27 (90) | 27 (84.4) | |

| Master's | 3 (10) | 5 (15.6) | |

| Organizational position | 0.543 c | ||

| Nurse | 26 (86.7) | 27 (84.4) | |

| Nurse manager | 4 (13.3) | 5 (15.6) | |

| Employment type | 0.571 c | ||

| Contractual | 13 (43.3) | 13 (40.6) | |

| Temporary | 4 (13.3) | 2 (6.3) | |

| Permanent | 13 (43.3) | 17 (53.1) | |

| Shift type | 0.416 b | ||

| Fixed | 11 (36.7) | 15 (46.9) | |

| Rotating | 19 (63.3) | 17 (53.1) | |

| Department of service | 0.441 b | ||

| Regular | 13 (43.3) | 17 (53.1) | |

| Special | 17 (56.7) | 15 (46.9) | |

| Marital status | 0.829 b | ||

| Married | 17 (56.7) | 19 (59.4) | |

| Single | 13 (43.3) | 13 (40.6) | |

| History of divorce | 0.738 c | ||

| Yes | 1 (3.3) | 1 (3.1) | |

| No | 29 (96.7) | 31 (96.9) | |

| Income | 0.529 b | ||

| Less than expenses | 10 (33.3) | 7 (21.9) | |

| Equal to expenses | 13 (43.3) | 18 (56.3) | |

| More than expenses | 7 (23.3) | 7 (21.9) | |

| Caring for COVID-19 patients | 0.570 b | ||

| Yes | 11 (36.7) | 14 (43.8) | |

| No | 19 (63.3) | 18 (56.3) | |

| History of COVID-19 infection | 0.465 b | ||

| Yes | 16 (53.3) | 20 (62.5) | |

| No | 14 (46.7) | 12 (37.5) | |

| Age of nurses | 5.90 ± 37.33 | 6.77 ± 35.87 | 0.371 d |

| Nurses' work experience | 3.85 ± 12.16 | 78.10 ± 3.51 | 0.144 d |

a Values are expressed as No. (%) or mean ± SD.

b Based on the chi-square test.

c Based on Fisher's exact test.

d Based on the Independent Samples t-test.

To compare nurses' job motivation in the intervention group before, immediately after, and one month after the intervention, Table 3 shows that repeated-measures ANOVA results indicated that mean job motivation and its dimensions differed significantly at least at one time point (P < 0.05); the only exception was the salary and benefits dimension, which did not show a significant difference. Bonferroni post-hoc comparisons are presented in Table 4.

| Variables | Before | Immediately | One Month After | Result of Repeated Measures ANOVA | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Time | Interaction | Group | ||||

| Recognition and appreciation | ||||||

| Intervention | 17.36 ± 2.48 | 20.93 ± 1.68 | 20.80 ± 1.62 | P < 0.001; η2 = 0.444 | P < 0.001; η2 = 0.440 | P < 0.001; η2 = 0.217 |

| Control | 17.43 ± 2.69 | 17.40 ± 2.66 | 17.50 ± 2.70 | |||

| Result of an independent t-test | P = 0.92 | P < 0.001; d = 2.24 | P < 0.001; d = 2.24 | - | - | - |

| Career advancement and development | ||||||

| Intervention | 11.53 ± 2.25 | 15.90 ± 2.41 | 15.26 ± 2.83 | P < 0.001; η2 = 0.395 | P < 0.001; η2 = 0.364 | P < 0.001; η2 = 0.277 |

| Control | 11.56 ± 2.38 | 11.62 ± 2.37 | 11.81 ± 2.40 | |||

| Result of an independent t-test | P = 0.91 | P < 0.001; d = 2.39 | P < 0.001; d = 2.62 | - | - | - |

| Nature of work | ||||||

| Intervention | 10.86 ± 2.72 | 14.40 ± 2.04 | 14.03 ± 2.25 | P < 0.001; η2 = 0.413 | P < 0.001; η2 = 0.379 | P < 0.001; η2 = 0.172 |

| Control | 11.03 ± 2.54 | 11.21 ± 2.58 | 11.06 ± 2.40 | |||

| Result of an independent t-test | P = 0.88 | P < 0.001; d = 2.34 | P < 0.001; d = 2.33 | - | - | - |

| Independence and responsibility | ||||||

| Intervention | 9.23 ± 2.72 | 11.06 ± 1.79 | 10.76 ± 1.99 | P < 0.001; η2 = 0.109 | P = 0.02; η2 = 0.106 | P = 0.001; η2 = 0.134 |

| Control | 8.75 ± 2.60 | 8.87 ± 2.59 | 8.56 ± 2.58 | |||

| Result of an independent t-test | P = 0.54 | P < 0.001; d = 2.24 | P < 0.001; d = 2.32 | - | - | - |

| Success and career advancement | ||||||

| Intervention | 6.33 ± 1.74 | 8.13 ± 1.27 | 8.10 ± 1.29 | P < 0.001; η2 = 0.186 | P < 0.001; η2 = 0.184 | P < 0.001; η2 = 0.192 |

| Control | 6.15 ± 1.91 | 6.28 ± 1.81 | 6.03 ± 1.87 | |||

| Result of an independent t-test | P = 0.68 | P < 0.001; d = 1.58 | P < 0.001; d = 1.62 | - | - | - |

| Internal factors | ||||||

| Intervention | 55.33 ± 6.19 | 70.43 ± 3.95 | 68.96 ± 5.08 | P < 0.001; η2 = 0.694 | P < 0.001; η2 = 0.662 | P < 0.001; η2 = 0.506 |

| Control | 54.93 ± 6.03 | 55.40 ± 6.15 | 54.96 ± 5.83 | |||

| Result of an independent t-test | P = 0.74 | P < 0.001; d = 5.21 | P < 0.001; d = 5.48 | - | - | - |

| Salary and benefits | ||||||

| Intervention | 8.98 ± 2.32 | 9.40 ± 1.93 | 9.53 ± 2.09 | P = 0.183; η2 = 0.028 | P = 0.293; η2 = 0.020 | P = 0.534; η2 = 0.006 |

| Control | 9.06 ± 2.21 | 9.18 ± 2.22 | 9.01 ± 2.24 | |||

| Result of an independent t-test | P = 0.78 | P = 0.39; d = 2.08 | P = 0.337; d = 2.17 | - | - | - |

| Workplace policy | ||||||

| Intervention | 10.56 ± 2.54 | 12.01 ± 1.96 | 12.33 ± 2.02 | P < 0.001; η2 = 0.170 | P < 0.001; η2 = 0.211 | P < 0.039; η2 = 0.069 |

| Control | 10.56 ± 2.03 | 10.46 ± 2.14 | 10.40 ± 2.31 | |||

| Result of an independent t-test | P = 0.57 | P = 0.005; d = 2.05 | P = 0.001; d = 2.17 | - | - | - |

| Relationships with others | ||||||

| Intervention | 16.96 ± 2.31 | 20.76 ± 1.99 | 21.03 ± 1.95 | P < 0.001; η2 = 0.438 | P < 0.001; η2 = 0.504 | P < 0.001; η2 = 0.367 |

| Control | 16.87 ± 2.23 | 16.56 ± 2.22 | 16.65 ± 2.26 | |||

| Result of an independent t-test | P = 0.74 | P < 0.001; d = 2.11 | P < 0.001; d = 2.12 | - | - | - |

| Job security | ||||||

| Intervention | 14.06 ± 3.19 | 15.96 ± 2.83 | 16.01 ± 2.66 | P = 0.002; η2 = 0.096 | P = 0.002; η2 = 0.096 | P = 0.034; η2 = 0.073 |

| Control | 14.01 ± 2.73 | 13.93 ± 2.71 | 14.06 ± 2.73 | |||

| Result of an independent t-test | P = 0.96 | P = 0.005; d = 2.77 | P = 0.006; d = 2.70 | - | - | - |

| Work environment conditions | ||||||

| Intervention | 11.90 ± 1.72 | 13.46 ± 1.43 | 13.73 ± 1.25 | P < 0.001; η2 = 0.325 | P < 0.001; η2 = 0.406 | P < 0.001; η2 = 0.157 |

| Control | 11.81 ± 1.78 | 11.71 ± 1.74 | 11.62 ± 1.79 | |||

| Result of an independent t-test | P = 0.94 | P < 0.001; d = 1.60 | P < 0.001; d = 1.55 | - | - | - |

| Supervision and monitoring by authorities | ||||||

| Intervention | 16.37 ± 2.23 | 18.13 ± 2.95 | 18.03 ± 2.84 | P = 0.011; η2 = 0.072 | P = 0.002; η2 = 0.098 | P = 0.020; η2 = 0.087 |

| Control | 16.37 ± 2.23 | 16.18 ± 2.27 | 16.21 ± 2.07 | |||

| Result of an independent t-test | P = 0.52 | P < 0.001; d = 2.62 | P = 0.005; d = 2.47 | - | - | - |

| External factors | ||||||

| Intervention | 78.06 ± 7.45 | 90.03 ± 5.77 | 90.66 ± 5.60 | P < 0.001; η2 = 0.426 | P < 0.001; η2 = 0.480 | P < 0.001; η2 = 0.383 |

| Control | 78.68 ± 7.35 | 78.06 ± 7.16 | 77.96 ± 6.89 | |||

| Result of an independent t-test | P = 0.72 | P < 0.001; d = 6.23 | P < 0.001; d = 6.31 | - | - | - |

| Overall job motivation | ||||||

| Intervention | 133.40 ± 10.30 | 160.46 ± 8.55 | 159.63 ± 8.48 | P < 0.001; η2 = 0.666 | P < 0.001; η2 = 0.680 | P < 0.001; η2 = 0.537 |

| Control | 133.62 ± 10.01 | 133.46 ± 9.89 | 132.93 ± 9.57 | |||

| Result of an independent t-test | P = 0.95 | P < 0.001; d = 7.96 | P < 0.001; d = 9.06 | - | - | - |

z Abbreviation: ANOVA, analysis of variance.

a Values are expressed as mean ± SD.

b η2 = partial eta-squared; effect sizes: 0.01 = small; 0.06 = moderate; 0.14 = large.

c d = Cohen’s d; effect sizes: 0.2 = small; 0.5 = moderate; 0.8 = large.

| Job Motivation and Its Dimensions | Mean Difference | P a |

|---|---|---|

| Internal factors | ||

| Recognition and appreciation | ||

| Before | ||

| Immediately after | -1.768 | < 0.001 |

| One month after | -1.748 | < 0.001 |

| Immediately | ||

| One month after | 0.020 | 1 |

| Career advancement and development | ||

| Before | ||

| Immediately after | -2.215 | < 0.001 |

| One month after | -1.992 | < 0.001 |

| Immediately | ||

| One month after | 0.223 | 0.524 |

| Nature of work | ||

| Before | ||

| Immediately after | -1.860 | < 0.001 |

| One month after | -1.599 | < 0.001 |

| Immediately | ||

| One month after | 0.261 | 0.08 |

| Independence and responsibility | ||

| Before | ||

| Immediately after | -0.979 | 0.005 |

| One month after | -0.673 | 0.120 |

| Immediately | ||

| One month after | 0.306 | 0.034 |

| Success and career promotion | ||

| Before | ||

| Immediately after | -0.962 | < 0.001 |

| One month after | -0.821 | 0.003 |

| Immediately | ||

| One month after | 0.142 | 0.547 |

| Intrinsic factors | ||

| Before | ||

| Immediately after | -7.784 | < 0.001 |

| One month after | -6.832 | < 0.001 |

| Immediately | ||

| One month after | 0.952 | 0.011 |

| Extrinsic factors | ||

| Salary and benefits | ||

| Before | ||

| Immediately after | -0.463 | 0.341 |

| One month after | -0.285 | 1 |

| Immediately | ||

| One month after | 0.177 | 0.220 |

| Workplace policy | ||

| Before | ||

| Immediately after | -0.853 | 0.003 |

| One month after | -0.989 | 0.001 |

| Immediately | ||

| One month after | -0.135 | 0.383 |

| Relationships with others | ||

| Before | ||

| Immediately after | -1.744 | < 0.001 |

| One month after | -1.924 | < 0.001 |

| Immediately | ||

| One month after | -0.180 | 0.092 |

| Job security | ||

| Before | ||

| Immediately after | -0.919 | 0.062 |

| One month after | -0.998 | 0.027 |

| Immediately | ||

| One month after | -0.079 | 0.530 |

| Work environment conditions | ||

| Before | ||

| Immediately after | -0.736 | < 0.001 |

| One month after | -0.823 | < 0.001 |

| Immediately | ||

| One month after | -0.086 | 0.518 |

| Supervision and monitoring by officials | ||

| Before | ||

| Immediately after | -0.956 | 0.043 |

| One month after | -0.922 | 0.090 |

| Immediately | ||

| One month after | 0.034 | 1 |

| Extrinsic factors | ||

| Before | ||

| Immediately after | -5.671 | < 0.001 |

| One month after | -5.941 | < 0.001 |

| Immediately | ||

| One month after | -0.270 | 0.951 |

| Overall, job motivation | ||

| Before | ||

| Immediately after | -13.455 | < 0.001 |

| One month after | -12.773 | < 0.001 |

| Immediately | ||

| One month after | 0.682 | 0.416 |

a P < 0.05 is statistically significant.

As Table 4 shows, in the intervention group, internal factors of job motivation, including recognition and appreciation, career advancement and development, nature of work, independence and responsibility, and success and promotion were significantly lower before the intervention than immediately after (P ≤ 0.001) and one month after the intervention (P ≤ 0.001). Scores were significantly higher immediately after the intervention than at one-month follow-up (P < 0.02).

For external factors of job motivation, including salary and benefits, workplace policy, relationships with others, job security, work environment conditions, and supervision by authorities, scores were significantly lower before the intervention than immediately after (P ≤ 0.001) and one month after the intervention (P ≤ 0.001). However, the external factors did not show a significant difference between immediately after the intervention and one month later (P = 0.45).

Finally, for the total job motivation score (the sum of internal and external factors), scores were significantly lower before the intervention than immediately after (P ≤ 0.001) and one month after the intervention (P ≤ 0.001). There was no significant difference between the immediate post-test and the one-month follow-up for the total score (P = 0.80).

To compare job motivation in the control group before, immediately after, and one month after the intervention, repeated-measures ANOVA results indicated no statistically significant differences in job motivation or any of its dimensions in the control group (P > 0.05). Repeated-measures ANOVA showed significant effects of time, group, and their interaction (P ≤ 0.001). Given the significant interaction effect, comparisons were made within each group across time points. Job motivation and its dimensions did not differ significantly at baseline between the groups, but differences were significant immediately and one month after the intervention (P ≤ 0.001). The mean score of job motivation and all its dimensions in the intervention group was significantly higher than in the control group at post-intervention assessments.

5. Discussion

This study aimed to determine the effectiveness of positive psychology group training on nurses' job motivation. At baseline, nurses in the intervention group (133.40 ± 10.30) and the control group (133.62 ± 10.01) had similar, moderate-to-high job motivation levels, with no statistically significant difference. However, immediately and one month after the intervention, mean job motivation scores differed significantly between the intervention and control groups. In other words, after implementing positive thinking training and comparing pre-test and post-test results, significant improvements were observed in the intervention group's job motivation, indicating the effectiveness of positive thinking training.

The study conducted by Hee and Kamaludin in Malaysia reported a high level of job motivation among nurses, identifying job security and adequate salary as the most influential motivational factors (42). Similarly, Ayalew et al. in Ethiopia evaluated the level of nurses’ job motivation as acceptable and favorable, demonstrating that salary and job security were the most significant determinants of motivation (43). In Saudi Arabia, Baljoon also assessed nurses’ job motivation as satisfactory and desirable, and further highlighted that factors such as personal recognition, performance-based promotion, written appreciation, encouragement of achievements, and public acknowledgment were among the most critical elements in fostering employee motivation (10).

Positive thinking skills may empower nurses by enhancing resilience. Constructive hope, goal-setting, an internal locus of control, and spiritual trust are characteristics that can help nurses cope with job difficulties. These personal traits can increase nurses' resistance to stressful work events (44). Positive affect facilitates sustained activity and adaptive behavior (45). Some studies have defined work motivation as a combination of energizing forces that originate both internally and beyond the individual, serving as the catalyst for work-related behavior and determining its form, direction, intensity, and persistence. In other words, it represents an intrinsic drive that propels an individual toward specific activities (46). Job motivation empowers individuals in their pursuit of objectives, mobilizing them into action. Since its sources stem from both internal and external factors, motivation can be regarded as a multidimensional psychological process that channels employee behaviors toward more effective goal achievement (47).

In his influential study, Herzberg highlighted that, within the domain of human resource management, motivation is defined as the process of stimulating employees to perform tasks and directing their efforts toward satisfactory job outcomes. He argued that enhancing and sustaining nurses’ job motivation at an optimal level constitutes a win–win strategy, and that organizations should consider the preservation of employee motivation at its highest standard as a core responsibility. According to Herzberg’s findings, motivational factors contribute to job satisfaction by fostering positive attitudes toward work and replacing employee indifference with engagement. In contrast, the absence of such factors, even at minimal levels, leads to dissatisfaction and discontent. Thus, the psychological reinforcement of motivation in the workplace not only enhances employees’ sense of fulfillment but also prevents the development of negative attitudes that ultimately result in job dissatisfaction (48).

Cultural factors, such as collectivism and religious beliefs in Iran, may enhance the effectiveness of positive psychology interventions by fostering group cohesion and spiritual optimism (49).

These results are consistent with various studies. Haryono et al. found that teaching positive thinking skills as part of positive psychology-based interventions significantly increased employee motivation and job satisfaction (50). Springer reported that positive psychology training had a positive and significant effect on employee job motivation (51). Mills et al. showed that positive psychology training influenced nurses' intrinsic motivation and willingness to perform professional acts, such as patient care, by changing hope for outcomes, patterns of positive and negative thinking, locus of control, goal setting, problem-solving, and reliance on spiritual resources (52). Other studies similarly indicate that positive psychology can increase self-efficacy and job motivation (10, 53-55).

One of the primary goals of positive psychology-based interventions is to improve quality of life and enhance job performance (56). Achieving achievement motivation is a central objective of positive psychology (57). Because positive thinking fosters a sense of self-efficacy, and self-efficacy plays a crucial role in the emergence of motivation, individuals who feel self-efficacious expect positive outcomes and choose appropriate tasks; their skills improve, self-efficacy increases, and they anticipate further positive outcomes (58).

Many nurses, after prolonged exposure to occupational stress, experience fatigue and may consider leaving their jobs. Job demotivation, if unaddressed, has negative consequences for patients, organizations, and nurses themselves. Reduced mental health, decreased self-efficacy, and lower motivation can increase absenteeism and reduce the quality of nursing services. Teaching stress-management strategies within a positive framework promotes nurses' health and well-being, reduces burnout and demotivation, and decreases staff losses. Improving interpersonal and self-management skills reduces emotional exhaustion and depersonalization while increasing personal accomplishment, which in turn supports job motivation (59).

A qualitative study in Japan found that healthcare personnel experienced declines in work motivation when providing end-of-life care during the pandemic; however, organizational support, managerial backing, team unity, and community efforts helped prevent professional isolation and maintain motivation (60). Other studies have reported significant declines in healthcare workers' job motivation during the pandemic across multiple dimensions (61). Extensive evidence suggests that work-related attitudes — including job motivation, job satisfaction, and work engagement — deteriorated in healthcare occupations during the COVID-19 crisis, largely due to staff shortages, increased workloads, long shifts, physical and mental exhaustion, anxiety, depression, and occupational burnout (62).

Based on the present study's findings and the topics covered in the positive-thinking training sessions (hope, positive and negative thinking, locus of control, goal-setting, problem-solving, prayer, and trust in God), significant improvements were observed in job motivation scores in the intervention group compared with pre-test measures. These findings suggest that positive-thinking education can meaningfully enhance nurses’ psychological hardiness by fostering constructive hope, clear goal orientation, an internal locus of control, and spiritual reliance — traits that support resilience when facing job-related stressors (44).

Numerous studies have demonstrated that granting authority and independence to nurses increases motivation, particularly intrinsic motivation. When managers create environments that support autonomy and employee participation in decision-making, employees perform tasks as commitments they choose rather than obligations. Studies in China, Italy, and Iran indicate that increasing employees' independence and authority is associated with higher job motivation (63-65). Compared to financial incentives or leadership training (66), positive psychology interventions are cost-effective, focus on intrinsic motivation, and offer a scalable approach for resource-constrained settings. In general, nursing managers should provide nurses with as much freedom and flexibility as possible regarding the tasks they perform and how they perform them. Allowing employees to choose tasks aligned with their interests can lead to better job outcomes; when skill level and task challenge match appropriately, individuals are likely to experience flow and satisfaction (29).

Policy-makers and healthcare managers are encouraged to increase nurses' job motivation by reforming payment methods, improving nurses' income and benefits to reflect workload and job difficulty, revising job descriptions across nursing levels, supporting managers, increasing nurses' participation in decision-making, enhancing dialogue between managers and nurses, and providing problem-solving training.

Based on the results of this study, several key implications for future research emerge to further build upon and refine our understanding of positive psychology interventions in nursing. The current study demonstrated the effectiveness of the intervention immediately and one-month post-training. Future research should incorporate longer follow-up periods (e.g., six months, one year, or more) to assess the sustainability of the improvements in job motivation. This would help determine if the effects are lasting or if periodic "booster" sessions are needed to maintain a high level of motivation over time.

While this study focused on an individual-level intervention, the text acknowledges the importance of organizational factors like autonomy, managerial support, and recognition. Future studies should explore the interaction between individual positive psychology training and the work environment. For instance, is the intervention more effective in organizations that already have a supportive culture? Or can this training help buffer nurses from the negative effects of a less supportive workplace?

Also, positive psychology interventions are a cost-effective alternative to financial incentives or leadership training. Future research should be designed to directly compare the effectiveness and cost-benefit of these different motivational strategies. Such studies would provide invaluable data for healthcare policymakers and managers when deciding how to allocate resources to support their nursing staff. In this study, the combination of in-person, synchronous, and asynchronous sessions was necessitated by COVID-19 constraints; varying engagement levels across modalities may have influenced outcomes. Future research should compare delivery methods.

5.1. Conclusions

Positive psychology training increased job motivation in this study, suggesting potential benefits for nurses in similar Iranian hospital settings, though further research is needed to confirm generalizability. Seven weeks of positive-thinking training led to increased job motivation among nurses in the intervention group. These findings indicate that empowering nursing human resources through positive psychology strategies is important in healthcare systems. Establishing infrastructure for conducting such training, allocating accessible educational content, forming focused discussion and group-training sessions centered on positive psychology, and providing training with the assistance of experts should be considered by nursing managers and healthcare administrators.

5.2. Research Limitations

Differences in participants' literacy levels and cultural backgrounds may have limited the accuracy of responses. Nurses may have answered conservatively out of concern that truthful responses could be detrimental, which may have biased results. The non-randomized design may have introduced selection bias, and the small sample size from a single hospital limits generalizability. External factors, such as COVID-19-related stressors, may have influenced results. Future studies should implement randomized controlled trials by randomly assigning nurses to intervention and control groups using a random number generator or software such as SPSS. The two-week gap in data collection between groups may have introduced temporal bias due to changes in hospital workload or pandemic-related stressors; future studies should collect baseline data simultaneously for both groups and use secure online platforms to minimize contamination.