1. Background

Hyperthyroidism, hypothyroidism, and goitre are the most common thyroid disorders. Moreover, thyroidectomy and parathyroidectomy are the most common head and neck surgical procedures (1). Thyroidectomy is recommended for benign diseases such as large symptomatic goitre and for the treatment of malignant diseases of the thyroid gland (2). In the early postoperative period, many patients suffer from a feeling of choking, stiffness, and pressure symptoms, pain in the neck and shoulders, and limited movement of the larynx. These factors are most likely caused by damage to the skin, muscles, or nerves outside the larynx during neck surgeries (3). Neck pain and bleeding are the most common complications after thyroidectomy (1). The cervical incision, endotracheal intubation, and hyperextension of the neck during thyroidectomy can cause postoperative discomfort and pain in the neck and shoulders (4). One of the serious complications of thyroidectomy surgery is bleeding. Reoperation due to bleeding may lead to further complications, including death. According to existing studies, the incidence of postoperative bleeding following thyroid gland surgery ranges from 0 to 4.2%. Therefore, every patient undergoing thyroidectomy requires close monitoring for at least 24 hours after surgery. Warning signs such as shortness of breath, neck edema, a sensation of pressure, and an abnormal amount of blood in the drain must be carefully observed (5). In general, it is the responsibility of the entire care team — not just the surgeon — to ensure that postoperative bleeding is managed as quickly as possible and in accordance with the highest standards of care (4). Pain management after thyroidectomy is a critical component of patient care and is associated with patient satisfaction and outcomes after thyroid surgery (6). The amount of pain after surgery depends on the extent of the surgery, the patient's pain threshold, and the patient's response to pain. Although drug therapy is the most common method for pain control, the prevalence of pain after surgery is still high (80%) (7). High levels of postoperative pain are associated with increased opioid use, decreased vital capacity, pneumonia, tachycardia, increased blood pressure, and delayed wound healing and recovery (8). Pharmacological interventions often entail significant side effects that impact both the physical and psychological well-being of patients. Analgesics, in particular, carry risks of addiction and drug dependence and may lead to hypotension, suppression of vital functions, drowsiness, nausea, vomiting, and even shock. In addition to these clinical concerns, such treatments are time-intensive for healthcare personnel and impose substantial financial burdens on the healthcare system (9). Nowadays, there is a growing emphasis on non-pharmacological approaches to pain relief — commonly referred to as complementary methods (9). Many complementary therapies, such as massage, soothing music, relaxation, mind-body techniques, reflexology, herbal medicine, hypnosis, and therapeutic touch, are available to manage pain, but massage therapy, in particular, appears to be a reasonable choice of complementary and alternative medicine after surgery (10). Massage therapy is a scientific and systematic manipulation of the soft tissues and muscles of the body to promote and maintain function and to aid healing and achieve therapeutic outcomes, including relaxation, comfort, and healing (11). A systematic review found that massage therapy may have immediate effects on neck and shoulder pain. However, no studies have shown that massage therapy is effective in a functional setting (12). Massage therapy improves blood flow, relaxes muscles, and stimulates the parasympathetic nervous system, and by stimulating the vagus nerve, it can be effective in improving physiological indicators. However, studies have provided conflicting results; some randomized controlled trials reported positive outcomes, and most high-quality studies did not yield positive results (13).

The results of a systematic review showed that massage therapy may reduce postoperative pain, although there are limitations in generalizing these findings due to the low quality of the methodology in the reviewed studies (14). Lee et al. concluded in a study that wound massage has a significant effect on reducing neck pain and voice changes after thyroidectomy (15). Despite the increasing use of complementary therapies in postoperative care, there remains limited empirical evidence regarding their effectiveness, especially in the context of open thyroidectomy. While massage therapy has shown promise in reducing neck and shoulder pain in general surgical populations, few studies have specifically evaluated its impact on postoperative pain and bleeding following thyroid surgery. Moreover, existing studies often suffer from methodological limitations, such as small sample sizes, lack of standardized massage protocols, or short follow-up periods, which restrict the generalizability of their findings.

Given the high prevalence of postoperative pain and the potential risks associated with pharmacological pain management — including opioid dependence, adverse effects, and increased healthcare costs — there is a pressing need to explore safe, effective, and accessible non-pharmacological interventions. Massage therapy, as a low-risk and cost-effective method, may offer significant benefits in this context.

2. Objectives

The present study was conducted with the aim of determining the effect of massage on pain and bleeding in patients undergoing open thyroidectomy in the operating room of a selected hospital affiliated with Isfahan University of Medical Sciences during the year 2023 - 2024.

3. Methods

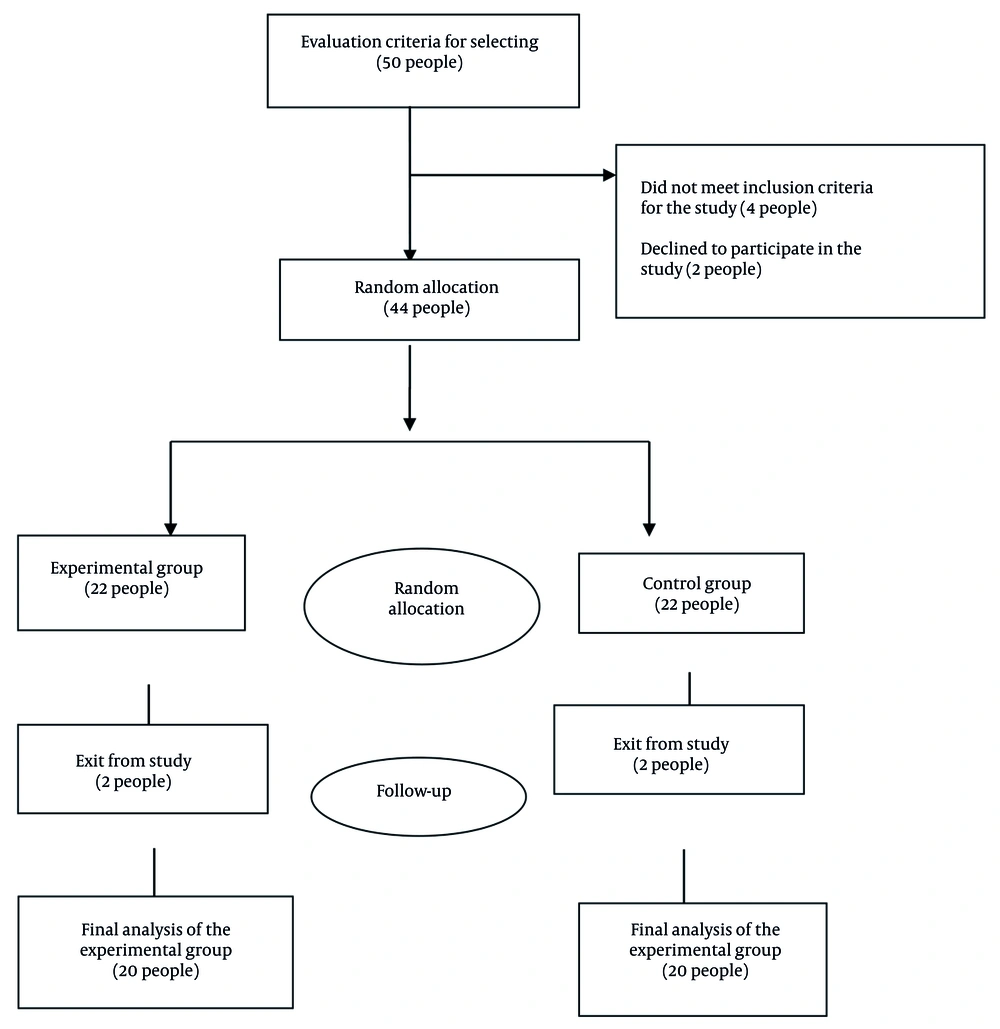

The present study was a randomized controlled clinical trial without blinding. The study protocol was determined based on internationally recognized guidelines for randomized clinical trials, including the SPIRIT 2025 statement and the ICH M11 guideline, which ensure methodological rigor, transparency, and ethical compliance (16). The research population consisted of patients undergoing total thyroidectomy and thyroid lobectomy surgery and hospitalized in the post-anesthesia care unit of Al-Zahra Hospital, Isfahan, between October 2024 and April 2025. Initially, the samples were selected using a convenience sampling method. Subsequently, they were randomly assigned to the intervention and control groups. The allocation of samples to the groups was carried out using sealed envelopes that had been prepared in advance based on a table of random numbers. Initially, the researcher used the random number table to assign odd numbers to the intervention group and even numbers to the control group. With eyes closed, the researcher placed a finger on a random point in the table and, following a predetermined direction, selected the required number of odd and even numbers. Each selected number was placed in a separate envelope. For each eligible participant, one envelope was opened, and based on whether the number inside was odd or even, the participant was assigned to either the intervention or control group. The sample size was calculated based on the results of a previous study (17) and the formula for comparing the means of two independent groups was used:

With a confidence factor of 95% and Z1 = 1.96, Z2 = 0.84, S1 = 1.1, S2 = 1.0, d = 0.95, and based on that, the required sample size was estimated to be 20 participants per group. Considering a potential 10% dropout rate, the initial recruitment target was increased to approximately 22 participants per group.

The inclusion criteria included patients undergoing total thyroidectomy and thyroid lobectomy with benign symptoms, willingness to participate in the study, no history of vascular or inflammatory diseases, diabetes, no history of receiving massage (six months before the study and until the final evaluation), no history of chronic pain such as migraine, awareness of time and place during the massage period, age between 18 - 70 years, no drug addiction, no history of coagulation disorders (18), stable hemodynamics: Systolic blood pressure between 90 and 120 mm Hg, mean arterial pressure above 60 mm Hg, heart rate between 60 and 100 beats per minute (19). The exclusion criteria were the patient's unwillingness to continue cooperation, hemodynamic instability during and after surgery, and patient death (18). Before starting the study, a demographic questionnaire and a Visual Analog Scale (VAS) Questionnaire were completed by asking the patient. The VAS is a simple and widely used psychometric tool for assessing subjective experiences such as pain, anxiety, or mood. It typically consists of a horizontal or vertical line measuring 10 centimeters (100 millimeters) in length, with endpoints labeled to represent extremes of the symptom — for example, "no pain" on one end and "worst imaginable pain" on the other. Patients are asked to mark a point on the line that best reflects the intensity of their experience. The distance from the starting point to the mark (measured in centimeters) is recorded as the VAS score, ranging from 0 to 10. This method is valued for its sensitivity to small changes, ease of use, and applicability in both clinical practice and research settings. In previous studies, the validity of this scale has been confirmed, and its reliability has been confirmed based on Cronbach's alpha of 0.91 (20, 21). Massage therapy was administered at three time points: During the recovery phase, one day after surgery, and three days after surgery. In contrast, pain intensity using the VAS was measured at five time points: Before surgery, during recovery, one day after surgery, three days after surgery, and one month postoperatively.

The amount of drainage and blood present in the Hemovac drain was measured. Hemovac is a closed-suction drain that is placed near the thyroid bed through a small skin incision following surgery. Its primary function is to evacuate blood and serous fluid, thereby reducing the risk of hematoma and allowing for postoperative bleeding monitoring. The volume of fluid collected in the drain can be measured, and this measurement is recorded by the researcher at 24 and 48 hours after surgery. In this study, blood samples for hemoglobin and hematocrit measurement were collected at three time points: Before surgery, and at 24 and 48 hours postoperatively. The sampling was performed by nurses, and the specimens were sent to the laboratory for analysis using Hematology Analyzer devices. The hemoglobin and hematocrit measurement was performed using the cyanmethemoglobin method with Drabkin’s solution from Sigma-Aldrich, under catalog number D5941. The results were recorded by the researcher and compared to evaluate changes in hemoglobin and hematocrit levels during the postoperative period.

3.1. Performance Massage Method

The researcher (first author) began performing the massage after completing a training course under the supervision of an experienced specialist who is a faculty member at Isfahan University of Medical Sciences, and after obtaining certification. The massage intervention was performed exclusively by the researcher on each patient. The massage trainer supervised both the quality and timing of the massage sessions to ensure adherence to the intervention protocol. In this study, the first massage session was conducted during the recovery day. To ensure patient comfort and muscle relaxation, the side-lying position was used. The patient lay on their side with the head stabilized, the lower leg straight, and the upper leg bent at a 90-degree angle with a pillow placed between the legs.

In this study, a massage oil (baby oil) with a light texture was used, which is easily absorbed by the skin without leaving a greasy or sticky residue. The oil was free of aromatic essences to avoid any interference with aromatherapy effects, ensuring that the intervention focused solely on the physical impact of massage. This type of oil was selected to maintain a neutral scent and allow for better control of intervention-related variables.

Before starting the massage therapy test, the researcher first prepared the patient and the patient's surroundings for the intervention. Companions of the patients were asked to leave the room to ensure a private environment for the massage procedure. In cases where companions insisted on staying in the room, they were instructed not to touch the patient or hold their hand during the session. Additionally, prior to the massage, all jewelry items — including bracelets, rings, watches, and similar accessories — were removed from the patients to avoid any interference with the massage process.

Performance massage is a combination of sports massage, therapeutic techniques, and relaxation methods that specifically targets key muscle groups. Its goal is to enhance physical performance, reduce muscular pain, increase range of motion, and prepare the body for intense activity or aid in post-activity recovery. This massage places special emphasis on the shoulders, neck, and lower back — areas commonly affected by prolonged sitting or repetitive movements (22).

The massage consisted of four stages.

1. Simple stroke technique: Starting from the first sacral vertebra (S1), strokes were applied parallel to the spine up to the first thoracic vertebra (T1), then outward toward the shoulders, and back down. This was repeated 10 times.

2. Spiraling stroke technique: Beginning again at S1, spiral strokes were applied across the back muscles up to T1 and then downward, repeated 10 times.

3. Walking stroke technique: Hands mimicked a walking motion from S1 to T1 and back down along the spine, repeated 10 times.

4. Focused massage on shoulder and neck muscles: All three techniques were repeated 10 times from T8 to T1 to target shoulder muscles. Finally, neck massage was performed from C1 to C7 using the effleurage technique, applying gentle circular pressure with both thumbs beside each vertebra, repeated 10 times per vertebra (22).

In the experimental group, the researcher performed massage therapy in three sessions. The duration of the massage therapy was 15 - 20 minutes. The first session was in the post-anesthesia care unit in the operating room. The second session was one day after surgery in the inpatient ward at the patient's bedside, and the third session was three days after surgery in the doctor's office. Massage therapy was not performed in the control group; however, both the control and intervention groups received the same medications prescribed by the surgeon: Levothyroxine, typically 1.6 µg/kg/day, adjusted based on TSH levels; calcium and vitamin D, with calcium carbonate at 500 - 1000 mg, 2 - 3 times/day, and vitamin D at 800 - 2000 IU/day or more if needed; and pain relief with acetaminophen or NSAIDs for short-term discomfort, at 500 - 1000 mg every 6 - 8 hours. Both groups also received identical routine postoperative care, which included avoiding heavy lifting and strenuous neck movements, encouraging gentle walking to promote circulation, recommending neck and shoulder exercises to prevent stiffness, starting with soft foods and liquids while avoiding hard or scratchy items, staying hydrated and eating a balanced diet to support healing, and managing constipation with fiber-rich foods and fluids.

3.2. Data Analysis

All data were analyzed using SPSS statistical software (version 23.0, IBM Corporation, Armonk, NY, USA). The Kolmogorov-Smirnov test was used to assess the normality of quantitative variables. To compare baseline quantitative variables between the two groups, either the independent t-test or the Mann-Whitney U test was applied, depending on data distribution. For categorical nominal variables, the chi-square test was used.

Repeated measures ANOVA was employed to compare pain and bleeding over time within each group. To compare the mean levels of pain and bleeding related to thyroidectomy between the intervention and control groups before and after the intervention, the independent t-test was used. A P-value less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

3.3. Ethical Considerations

This article is derived from a master's thesis in operating room technology approved by Isfahan University of Medical Sciences and Services with the ethics code IR.MUI.MED.REC.1403.127 Written informed consent was obtained from all patients, and they were assured that all their information would remain confidential to the researcher. This article was approved by the Clinical Trial Registration Center with the code IRCT20240702062311N1.

4. Results

This randomized controlled clinical trial study was conducted on 44 patients; however, 4 patients withdrew due to unwillingness to cooperate. As a result, the final analysis was performed on 40 patients, with 20 individuals in each group. As shown in the consort diagram (Figure 1), the recruitment, allocation, follow-up, and analysis phases are detailed.

The results showed that the mean age of the patients in the experimental group was 46.65 years, and in the control group, it was 43.25 years. Additionally, 40% of the patients in the experimental group had a low-level education, and 35% had a university education. In the control group, 50% of the patients had a university education. Sixty percent of the patients in the experimental group and 55% of the patients in the control group were married, and the two groups were not statistically significantly different and were homogeneous (P < 0.05, Table 1).

| Variables | Control | Experimental | P-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | 1 b | ||

| Women | 20 (100) | 20 (100) | |

| Men | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | |

| Education | 0.37 b | ||

| Below diploma | 4 (20) | 8 (40) | |

| Diploma | 6 (30) | 5 (25) | |

| University education | 10 (50) | 7 (35) | |

| Marriage | 0.83 b | ||

| Single | 5 (25) | 3 (15) | |

| Married | 11 (55) | 12 (60) | |

| Widow | 3 (15) | 3 (15) | |

| Divorced | 1 (5) | 2 (10) | |

| Job | 0.76 b | ||

| Employed | 11 (55) | 9 (45) | |

| Un-employed | 2 (10) | 1 (5) | |

| Retired | 1 (5) | 2 (10) | |

| Housewife | 6 (30) | 8 (40) | |

| Income | 0.83 b | ||

| Less than living expenses | 1 (5) | 1 (5) | |

| Equal to living expenses | 17 (85) | 18 (90) | |

| More than living expenses | 2 (10) | 1 (5) | |

| Age (mean ± SD) | 43.25 ± 12.61 | 46.65 ± 12.49 | 0.39 c |

a Values are expressed as No. (%) unless indicated.

b Chi-square.

c Independent t-test.

The results of the repeated measures analysis of variance test showed that the mean pain score changed significantly over time, decreasing in the experimental group (P < 0.001). Also, the results of the independent t-test showed that the two groups did not have a statistically significant difference before the study (P = 0.88). However, at the times examined after the intervention, this difference was significant (P < 0.001, Table 2).

| Variables | Control | Experimental | The Interaction of Time and Group | Between-Group Comparison (P) b | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mauchly's Test | Greenhouse-Geisser | ||||

| Pain | χ2 = 40.47, P < 0.001 | F = 47.222, P < 0.001 | |||

| Before the intervention | 8.80 ± 0.23 | 8.75 ± 0.23 | 0.88 | ||

| In recovery | 8.85 ± 0.22 | 8.05 ± 0.22 | 0.01 | ||

| The day after surgery | 8.25 ± 0.28 | 7.05 ± 0.28 | 0.005 | ||

| 3 days after surgery | 7.75 ± 0.36 | 5.75 ± 0.36 | < 0.001 | ||

| One month after surgery | 4.45 ± 0.25 | 2.55 ± 0.25 | < 0.001 | ||

| P-value c | 0.05 | < 0.001 | - | - | - |

a Values are expressed as mean ± SD.

b Independent t-test.

c Analysis of variance with repeated measures.

The results showed that in both the experimental and control groups, the volume of blood inside the patient's drain increased significantly (P < 0.001) at 24 and 48 hours after surgery. This means that the intervention failed to reduce the volume of bleeding after surgery. The comparison of the experimental and control groups in terms of bleeding at 24 hours (P = 0.79) and 48 hours (P = 0.93) after surgery did not show a significant difference (Table 3).

| Variable | Control | Experimental | Between-Group Comparison (P) b |

|---|---|---|---|

| Blood volume in the drain | |||

| 24 hours after surgery | 60.48 ± 50.169 | 34.57 ± 00.174 | 0.79 |

| 48 hours after surgery | 47.48 ± 50.211 | 07.62 ± 00.213 | 0.93 |

a Values are expressed as mean ± SD.

b Independent t-test.

The results showed that the two groups did not have a statistically significant difference in hemoglobin score before the study, 24 and 48 hours after the intervention (P > 0.05, Table 4).

| Variables | Control | Experimental | Between-Group Comparison (P) b |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hematocrit | |||

| Before the intervention | 39.97 ± 3.22 | 39.63 ± 3.43 | 0.74 |

| 24 hours after surgery | 38.03 ± 3.58 | 38.41 ± 3.66 | 0.73 |

| 48 hours after surgery | 37.39 ± 3.34 | 37.97 ± 3.67 | 0.60 |

| Hemoglobin | |||

| Before the intervention | 13.52 ± 1.60 | 13.50 ± 1.78 | 0.97 |

| 24 hours after surgery | 13.09 ± 1.65 | 13.09 ± 1.81 | 0.93 |

| 48 hours after surgery | 12.91 ± 1.63 | 12.93 ± 1.83 | 0.95 |

a Values are expressed as mean ± SD.

b Independent t-test.

5. Discussion

The results showed that the pain score in the experimental group decreased significantly over time. Although the pain level in the control group also decreased significantly over time, the comparison of the pain score one month after the intervention in the experimental group was lower than in the control group, which can be attributed to the effect of the intervention (massage). In line with the present study, the study by Lee et al. showed that the feeling of discomfort in the neck area in patients undergoing thyroidectomy was significantly reduced after massage therapy. The difference between the present study and the study by Lee et al. was that in the latter, massage of the wound area in the neck started one month after surgery and continued for 12 weeks. In contrast, in the present study, massage therapy was performed in three 20-minute sessions: The first session in the post-anesthesia care unit in the operating room, the second session one day after surgery in the inpatient ward at the patient's bedside, and the third session three days after surgery in the doctor's office. Therefore, although the method and duration of massage in the two studies are different, the results indicate a positive effect of massage on postoperative pain (15).

Sanabria et al. stated in a review study that one way to relieve pain in patients after thyroidectomy is to massage the wound area (5). Although the present study differs from the study by Sanabria et al. in terms of the location of the massage, the results showed that massage therapy is effective in reducing patients' pain. In the present study, massage was performed on the back and neck vertebrae, but in the study by Sanabria et al., it was reported that massage of the wound area reduces pain after thyroidectomy. However, the study by Albert et al., which was conducted on heart surgery patients, showed that the average pain scores of patients after massage therapy were not statistically significantly different from those before the intervention, which is not consistent with the results of our study. The reason for the discrepancy between the aforementioned study and the present study may be that the aforementioned study included all heart surgery patients, including those undergoing heart valve repair or replacement, and those who had both procedures performed simultaneously. Due to the different duration of the surgery, the location and amount of pain in these patients will be different from each other (23). Hattan et al.'s study found that massage did not significantly reduce pain in patients undergoing coronary artery bypass graft surgery, which is not consistent with the results of our study; perhaps the small sample size in this study (7 patients in the experimental group and 9 in the control group) was one of the factors affecting the results of this study (24). It seems that the way in which massage is used and performed, the time of use, the frequency and duration of massage, and the type of surgery can be effective in controlling pain.

The results showed that massage had no effect on bleeding (drain secretions, hemoglobin, and hematocrit) and could not reduce bleeding after thyroidectomy. Some studies in this field have investigated the effect of uterine massage after cesarean section on bleeding and have shown the effect of massage on reducing postpartum and cesarean section bleeding (25, 26). However, no study was found that investigated the effect of massage on bleeding after surgery. Therefore, studies that examined the effect of massage on bleeding in hospitalized patients were reviewed. In this regard, the study by Molaei et al. showed that massage has no effect on preventing cerebral hemorrhage in premature infants hospitalized in the intensive care unit (27). Also, Di Ianni et al. reported in a study that vitreous hemorrhage caused by papilloma occurs following neck massage (28). In the referenced case study, the patient was predisposed to complications due to underlying intracranial hypertension and the direct application of massage to the neck region. These factors likely contributed to the observed optic disc hemorrhage (28). However, in our study, patients with a history of intracranial hypertension were excluded to minimize such risks. Furthermore, the massage procedures in our protocol were carefully designed to avoid the surgical site and were performed at a safe distance from the neck area. These precautions were implemented to ensure patient safety and uphold ethical standards throughout the study. In the present study, massage had no effect on the amount of bleeding and hemoglobin and hematocrit of patients. In this regard, a study stated that massage after surgery causes manipulation of tissues, including blood vessels, and if vessels that have been torn and are bleeding, their bleeding increases if they are manipulated (29). Therefore, it seems that more study is needed in this field.

5.1. Conclusions

The findings of this study demonstrate that massage therapy significantly reduces postoperative pain in patients undergoing thyroidectomy. However, the study found no significant effect of massage on postoperative bleeding. To strengthen clinical practice and ensure patient safety, future research should focus on identifying the most effective timing, frequency, and techniques of massage therapy across diverse surgical procedures. Moreover, larger, methodologically rigorous trials are needed to further validate these findings and explore massage’s broader role in surgical recovery. Integrating massage therapy into postoperative protocols may ultimately improve patient outcomes and satisfaction, provided its application is guided by evidence-based standards.

5.2. Strengths of the Present Study

- Use of a standardized massage protocol under the supervision of an experienced specialist, which enhanced the procedural credibility of the intervention.

- Implementation of the intervention by a single trained and consistent individual (the researcher), which minimized individual variation in massage delivery.

- Adherence to ethical principles and provision of a private environment for each patient, which increased participant comfort and cooperation.

5.3. Limitations

The present study has several limitations. Pain is a complex multidimensional experience influenced by psychological, social, behavioral, emotional, and environmental factors that are difficult to control. These factors may affect pain scores, especially in a study with a small sample size. Additionally, limited sampling from a single healthcare center may reduce the generalizability of the findings.