1. Background

Type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) is a global health crisis and one of the most prevalent non-communicable diseases of the 21st century. Characterized by insulin resistance and relative insulin deficiency, T2DM leads to chronic hyperglycemia and is associated with a wide range of metabolic, vascular, and neurological complications (1). The World Health Organization (WHO) estimates that diabetes will be the seventh leading cause of death by 2030, with T2DM representing over 90% of all diabetes cases. The disease exerts a substantial burden not only on individuals but also on healthcare systems, economies, and societies at large (2). The worldwide prevalence of T2DM has increased dramatically in recent decades due to a confluence of factors, including population aging, urbanization, reduced physical activity, and unhealthy dietary habits. According to the International Diabetes Federation (IDF), the number of adults living with diabetes rose from 108 million in 1980 to over 537 million in 2021, and this number is projected to reach 643 million by 2030 (3). This epidemic is not limited to high-income countries; low- and middle-income nations now bear the greatest share of the global diabetes burden, often with limited healthcare infrastructure to manage the disease effectively (4).

Beyond its metabolic and physiological dimensions, T2DM is recognized as a complex biopsychosocial condition. Long-term disease management requires individuals to make continuous lifestyle modifications, adhere to complex medication regimens, and monitor blood glucose levels — tasks that can be cognitively, emotionally, and financially taxing (5). Moreover, the potential for serious complications, such as retinopathy, nephropathy, neuropathy, and cardiovascular disease, introduces additional layers of stress and fear that can affect patients’ mental well-being. The chronic and progressive nature of T2DM often transforms it into a life-defining experience, influencing personal identity, social relationships, and quality of life (6).

Living with T2DM often imposes substantial psychological stress on individuals, including the burden of lifelong disease management, dietary restrictions, fear of complications, and social stigma. Numerous studies have demonstrated that people with T2DM are at increased risk for depression, anxiety, and psychological distress (7). Depression is estimated to occur in approximately 20 - 30% of adults with T2DM, a rate significantly higher than in the general population (4). These psychological issues can impair self-care behaviors, medication adherence, glycemic control, and overall quality of life, thereby creating a vicious cycle that exacerbates both physical and mental health outcomes (8). The complex interplay between emotional well-being and metabolic control necessitates a more integrated approach to diabetes management — one that addresses both psychological and physiological dimensions.

Interpersonal therapy (IPT) is grounded in the interpersonal theory of psychiatry, primarily developed by Harry Stack Sullivan (1953), which posits that psychological distress arises from disruptions in interpersonal relationships (9). Sullivan emphasized that human behavior and mental health are shaped by interactions with others, and disturbances in these relationships can contribute to psychiatric symptoms, including depression (10). Building on this, IPT was formalized by Klerman et al. in 1984 as a time-limited, structured psychotherapy designed to address interpersonal difficulties associated with depression (11). The theoretical framework of IPT integrates Sullivan’s interpersonal theory with attachment theory (12), which highlights the role of secure interpersonal bonds in fostering emotional well-being. The IPT posits that depression is often triggered or exacerbated by four key interpersonal problem areas: Grief (loss of significant relationships), role disputes (conflicts in relationships), role transitions (difficulty adapting to life changes), and interpersonal deficits (lack of social skills or support) (13).

The IPT is well-suited for T2DM patients as it targets interpersonal stressors like family conflicts, social isolation, or grief, which are common due to the condition. Unlike cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT), which focuses on cognitive distortions and self-management, or mindfulness-based approaches that emphasize present-moment awareness, IPT resolves interpersonal conflicts and strengthens social support. It helps patients manage family expectations or role transitions, enhancing psychological resilience and diabetes self-care (14).

Emerging evidence suggests that psychotherapeutic interventions, including cognitive-behavioral therapy and mindfulness-based approaches, can effectively improve psychological outcomes in people with T2DM (15, 16). However, the application of IPT specifically in this population has been relatively understudied. While IPT has shown efficacy in reducing depressive symptoms across diverse clinical groups (17), there is a notable lack of randomized controlled trials (RCTs) evaluating IPT’s impact on perceived social support or its long-term effects in T2DM patients, particularly in addressing disease-specific interpersonal challenges like social stigma or family conflicts over disease management. This gap limits the understanding of IPT’s potential to enhance psychosocial outcomes critical for T2DM care. Furthermore, there is a paucity of RCTs examining the sustained effects of IPT beyond the immediate post-intervention phase, especially in culturally diverse populations.

2. Objectives

The present randomized controlled trial (RCT) aimed to determine the efficacy of IPT in improving perceived social support and depressive symptoms among adults with type 2 diabetes. By doing so, the study seeks to contribute to a more holistic understanding of diabetes care and offer practical implications for integrating psychotherapeutic approaches into chronic disease management.

3. Methods

3.1. Study Design

This study was a RCT designed to evaluate the efficacy of IPT in adults with T2DM experiencing depressive symptoms joining an outpatient clinic in Tehran, Iran, in 2025. The study adhered to ethical standards, with approval from the Ethics Committee of Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences (IR.SBMU.PHARMACY.REC.1403.208). Furthermore, the study was registered with the Iranian Clinical Trials Registry (IRCT) under the ID: IRCT20240509061721N3.

3.2. Participants

A total of 150 adults aged 18 - 65 years with a confirmed T2DM diagnosis were screened for eligibility using the Beck Depression Inventory-II (BDI-II). A cutoff score of BDI-II ≥ 14 was required, indicating at least mild depressive symptoms (18). Of the 150 screened, 110 met the inclusion criteria and were enrolled. Exclusion criteria included severe psychiatric disorders (e.g., bipolar disorder, schizophrenia, psychosis), active substance abuse, cognitive impairment precluding consent, or participation in concurrent psychotherapy. Sample size was calculated using G*Power, assuming a medium effect size (Cohen’s d = 0.5) for Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support (MSPSS) and BDI-II outcomes, with 80% power and alpha = 0.05 for repeated-measures analysis of variance (ANOVA) (within-between interaction), requiring a minimum of 98 participants (49 per group). To account for an anticipated 10% attrition, 110 participants (55 per group) were recruited. Participants were randomly assigned to the intervention (n = 55) or control (n = 55) group using a computer-generated random number sequence for balanced allocation. Due to the nature of the intervention, blinding of participants and therapists was not feasible, as participants were aware of receiving psychotherapy or standard care, and therapists were trained in IPT delivery. However, outcome assessors administering the MSPSS and BDI-II were blinded to group assignments to minimize bias in data collection.

3.3. Instruments

The primary outcomes of this study were perceived social support, assessed using the MSPSS, and depressive symptoms, assessed using the BDI-II. No secondary outcomes were predefined, as the study focused exclusively on these psychosocial outcomes. The tools used in the study were as follows:

1. Demographic variables: Collected variables included age, gender, marital status, education level, employment status, and duration of T2DM diagnosis. These were assessed to ensure baseline comparability and explore potential moderating effects on outcomes.

2. Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support: A 12-item self-report questionnaire measuring perceived social support from family, friends, and significant others. Items are scored on a 7-point Likert scale (1 = very strongly disagree, 7 = very strongly agree), with total scores ranging from 12 to 84. Higher scores indicate greater perceived support (19). The MSPSS has high reliability (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.84) and validity in the Iranian context. Specifically, it showed strong construct validity through confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) with a good model fit (CFI = 0.93, RMSEA = 0.06) and convergent validity through significant correlations with measures of psychological well-being (r = 0.62, P < 0.01). Test-retest reliability, an indicator of external reliability, was reported as r = 0.85 over a two-week interval in the Persian validation study (20).

3. Beck Depression Inventory-II: A 21-item self-report scale assessing depressive symptoms based on DSM-IV criteria (21). Items are scored on a 4-point scale (0 = minimal, 3 = severe), with total scores ranging from 0 to 63. A score of ≥ 14 indicates mild to severe depression. The Persian version of the BDI-II has excellent reliability (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.87) and validity for detecting depression in Iran. It demonstrated strong construct validity through CFA with a CFI = 0.91 and RMSEA = 0.07 and criterion validity through significant correlations with clinical diagnoses of depression (r = 0.72, P < 0.01). Test-retest reliability, an indicator of external reliability, was reported as r = 0.74 over a one-month interval in the Persian validation study (22).

Data were gathered at three time points: Baseline, before intervention (T0), immediately post-intervention, approximately 10 weeks after baseline (T1), and two-month follow-up after intervention completion (T2).

3.4. Intervention

The intervention group (n = 51) received 10 weekly group sessions of IPT, each lasting 50 - 60 minutes, delivered by licensed clinical psychologists certified in IPT. Participants were divided into 10 groups, with 5 - 6 participants per group. A social media platform (Bale) was used to provide additional support, encouragement, and to address participants’ questions outside of session times, enhancing accessibility and engagement. The IPT was selected as the intervention based on its established efficacy in treating depression by addressing interpersonal stressors, which are particularly relevant for T2DM patients who often face relationship challenges due to chronic illness demands (23). Grounded in Sullivan’s interpersonal theory (9) and Bowlby’s attachment theory (12), IPT targets four key interpersonal problem areas — grief, role disputes, role transitions, and interpersonal deficits — that contribute to psychological distress. In the context of T2DM, these issues manifest as conflicts over disease management (e.g., dietary adherence), grief over health-related losses, or difficulties adapting to lifestyle changes post-diagnosis (23). The intervention was manualized, tailored for T2DM patients, and adapted to address disease-specific interpersonal challenges, such as negotiating family expectations or coping with social isolation due to chronic illness (24). The structure of the intervention is detailed in Table 1.

| Weeks | Phases | Objectives | Key Activities |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 - 2 | Initial assessment and formulation | Identify interpersonal stressors; Establish therapeutic alliance | Conduct interpersonal inventory; Select focal problem area (e.g., role disputes related to T2DM management); Provide psychoeducation on depression and T2DM |

| 3 - 6 | Active treatment (core phase) | Address focal interpersonal issue; Enhance communication and coping skills | Use role-playing, communication analysis, and problem-solving to address grief, role disputes, transitions, or deficits; Link interpersonal functioning to T2DM self-care |

| 7 - 8 | Active treatment (deepening) | Reinforce skills; Address secondary interpersonal issues | Explore additional interpersonal challenges (e.g., family conflicts over dietary adherence); Practice adaptive strategies; Monitor progress in T2DM management |

| 9 - 10 | Consolidation and termination | Review progress; Plan for maintenance | Consolidate learned skills; Develop relapse prevention plan; Provide referrals to community resources (e.g., diabetes support groups) |

Therapists underwent rigorous training and weekly supervision to ensure fidelity to the IPT protocol. Sessions were conducted in outpatient settings, with telehealth options to accommodate participants. The therapy incorporated T2DM-specific content, such as addressing interpersonal barriers to medication adherence or dietary compliance. For example, participants with role disputes were guided to negotiate family expectations, while those with role transitions explored adjustments to lifestyle changes post-T2DM diagnosis. Psychoeducation emphasized the interplay between interpersonal functioning, mental health, and diabetes management.

The control group received standard care, consisting of routine endocrinology consultations for T2DM management (e.g., medication adjustments, blood glucose monitoring) and access to general mental health resources, such as informational pamphlets on stress management provided during clinic visits. Structured psychotherapy was explicitly excluded, and participants were monitored via self-report at T1 and T2 to ensure no access to psychotherapy, minimizing contamination risk.

3.5. Statistical Analysis

Descriptive statistics, including means and standard deviations for MSPSS and BDI-II scores, as well as means and frequencies for demographic variables (e.g., age, gender, marital status, education level, employment status, and T2DM duration), were calculated for both groups at T0, T1, and T2 to summarize the data. Baseline demographic and clinical characteristics were compared using independent t-tests for continuous variables (e.g., age, T2DM duration) and chi-square tests for categorical variables (e.g., gender, marital status). Repeated-measures ANOVA was conducted to examine changes in MSPSS and BDI-II scores across T0, T1, and T2 within and between groups. Post-hoc pairwise comparisons with Bonferroni correction identified specific differences. Intention-to-treat (ITT) analysis with multiple imputation (5 imputations) addressed missing data due to attrition. Effect sizes were calculated using Cohen’s d for between-group and within-group changes. Covariates (gender, marital status) were included in secondary analyses to explore moderating effects. Statistical significance was set at P < 0.05. A linear mixed-effects model (LMM) was also applied to confirm findings, accounting for participant-level variability. Data were analyzed using SPSS version 26.0.

3.6. Ethical Considerations

The research was conducted in accordance with the ethical principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki (25). Ethical approval was obtained from the Ethics Committee of Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences (IR.SBMU.PHARMACY.REC.1403.208). Written informed consent was obtained from all participants prior to inclusion. Participant confidentiality was strictly preserved, and individuals had the right to withdraw from the study at any point without any consequences.

4. Results

4.1. Attrition

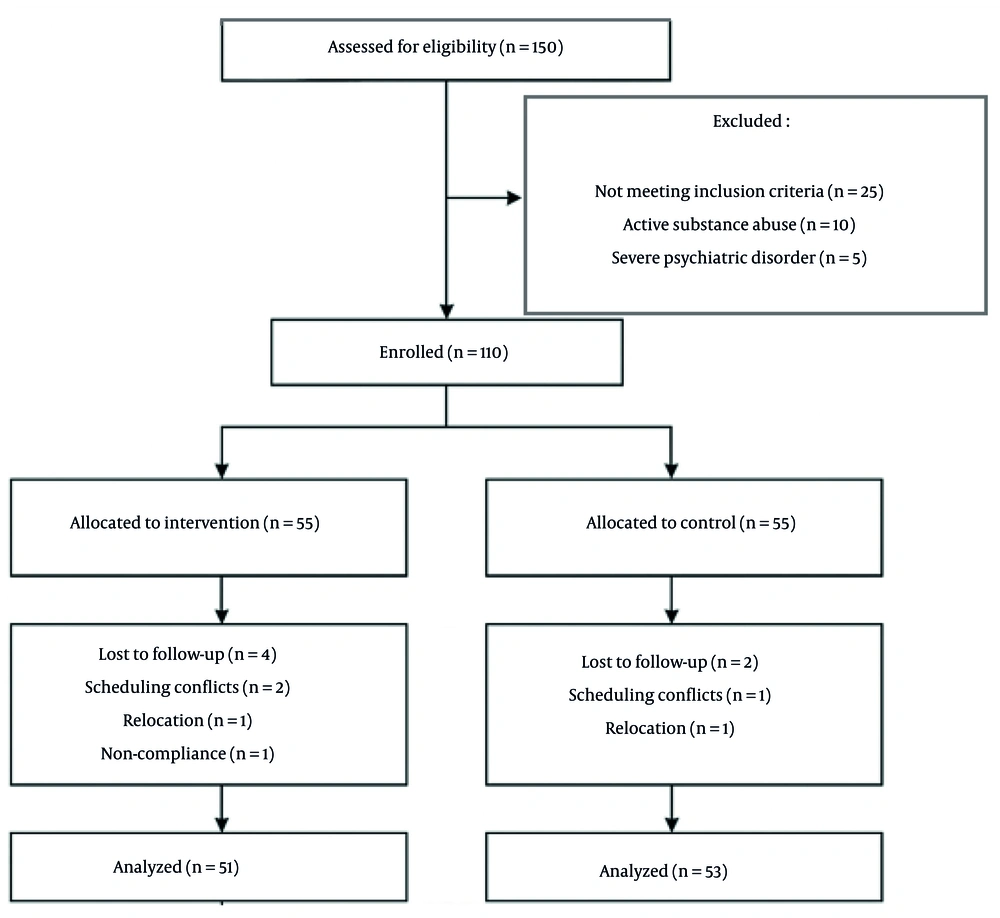

The low attrition rate (5.45%) is commendable, and the use of ITT analysis with multiple imputation is appropriate. However, the manuscript does not report the results of a sensitivity analysis to confirm that the imputation method did not unduly influence findings. Including such an analysis would strengthen confidence in the robustness of the results. More details are provided in Figure 1.

4.2. Baseline Characteristics

A total of 150 adults with T2DM were screened for eligibility, with 110 meeting inclusion criteria and randomized equally to the intervention or control group. Of these, 104 completed the study, with 51 in the intervention group and 53 in the control group, as detailed in the CONSORT flowchart (Figure 1). At baseline, no significant differences were observed between the intervention (n = 51) and control (n = 53) groups in demographic or clinical variables (all P > 0.05). The mean age was comparable between groups, with a slight variation in gender distribution (more females in the intervention group) and other demographic variables (Table 2).

| Variables | IPT (n = 51) | Control (n = 53) | P-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (y) | 50.8 ± 9.2 | 54.6 ± 8.9 | 0.07 |

| Gender | 0.25 | ||

| Male | 23 (45.1) | 30 (56.6) | |

| Female | 28 (54.9) | 23 (43.4) | |

| Marital status | 0.18 | ||

| Married | 32 (62.7) | 27 (50.9) | |

| Single | 19 (37.3) | 26 (49.1) | |

| Education | 0.12 | ||

| Elementary or lower | 8 (15.7) | 11 (20.8) | |

| High school | 17 (33.3) | 23 (43.4) | |

| Associate degree | 10 (19.6) | 8 (15.1) | |

| Bachelor’s degree or higher | 16 (31.4) | 11 (20.8) | |

| Employment status | 0.19 | ||

| Employed | 30 (58.8) | 24 (45.3) | |

| Unemployed | 21 (41.2) | 29 (54.7) | |

| T2DM duration | 6.8 ± 3.8 | 9.3 ± 4.7 | 0.08 |

| MSPSS score | 43.7 ± 11.2 | 46.1 ± 10.8 | 0.31 |

| BDI-II score | 23.8 ± 6.1 | 21.9 ± 5.8 | 0.15 |

Abbreviations: IPT, interpersonal therapy; T2DM, type 2 diabetes mellitus; MSPSS, Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support; BDI-II, Beck Depression Inventory-II.

a Values are expressed as No. (%) or mean ± SD.

4.3. Changes in Perceived Social Support (MSPSS)

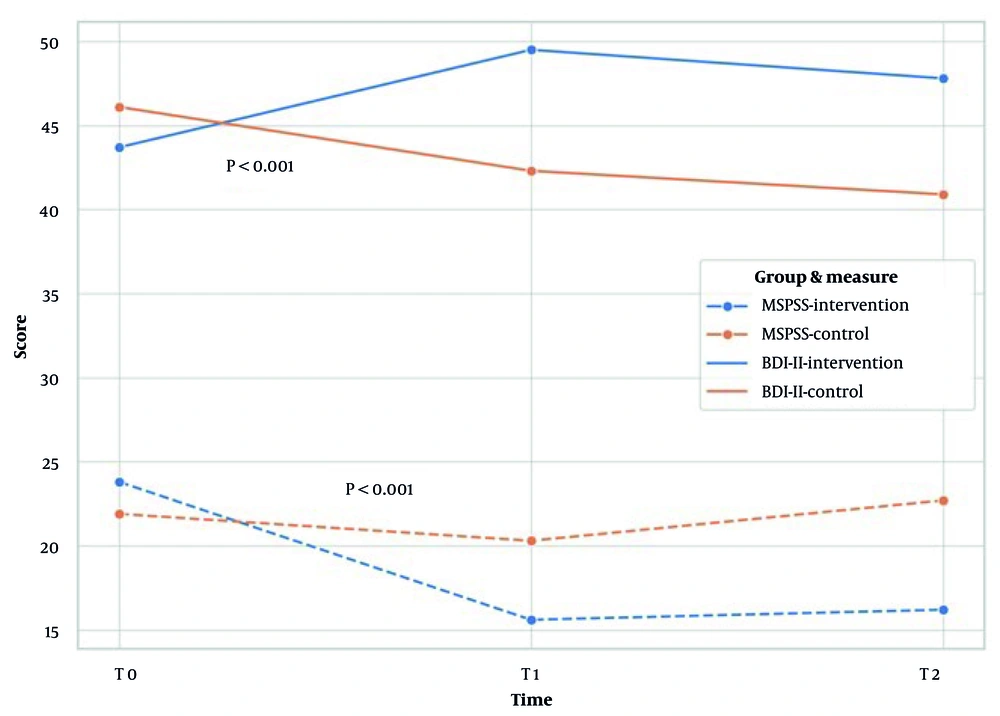

The assumption of homogeneity of variances was met for MSPSS scores across groups and time points, as confirmed by Levene’s test (all P > 0.05). Repeated-measures ANOVA revealed a significant time-by-group interaction for MSPSS scores (P < 0.001). The intervention group significantly increased perceived social support from T0 to T1 (P < 0.001) and maintained elevated levels at T2 (P < 0.01), while the control group showed a decline (P < 0.05), as determined by Bonferroni-corrected post hoc tests. Between-group differences were significant at T1 and T2 (both P < 0.001). Gender moderated outcomes, with females showing greater improvement in the intervention group (P = 0.03). Marital status also moderated effects, with married participants showing larger gains (P = 0.04) (Table 3 and Figure 2).

| Outcomes and Time | Intervention (n = 51) | Control (n = 53) | Between-Group Effect (P-Value, Cohen’s d) |

|---|---|---|---|

| MSPSS | |||

| T0 | 43.7 ± 11.2 | 46.1 ± 10.8 | 0.31, 0.22 |

| T1 | 58.4 ± 9.8 | - | 42.3 ± 10.1 |

| T2 | 56.2 ± 10.3 | 41.8 ± 9.7 | < 0.001, 1.4 |

| Within-group effect (P-value, Cohen’s d) | |||

| T0 vs. T1 | < 0.001, 1.3 | < 0.05, -0.4 | |

| T0 vs. T2 | < 0.01, 1.1 | < 0.05, -0.5 | |

| BDI-II | |||

| T0 | 23.8 ± 6.1 | 21.9 ± 5.8 | 0.15, 0.32 |

| T1 | 14.2 ± 4.9 | 21.5 ± 5.7 | < 0.001, 1.3 |

| T2 | 15.1 ± 5.2 | 22.7 ± 6.0 | < 0.001, 1.2 |

| Within-group effect (P-value, Cohen’s d) | |||

| T0 vs. T1 | 0.001, -1.6 | 0.08, -0.1 | |

| T0 vs. T2 | 0.001, -1.4 | 0.05, 0.2 |

Abbreviations: MSPSS, Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support; BDI-II, Beck Depression Inventory-II; T0, baseline; T1, post-intervention; T2, two-month follow-up.

a Values are presented as Mean ± SD, based on Bonferroni-corrected post hoc tests.

4.4. Changes in Depressive Symptoms (Beck Depression Inventory-II)

The assumption of homogeneity of variances was met for BDI-II scores across groups and time points, as confirmed by Levene’s test (all P > 0.05). A significant time-by-group interaction was observed for BDI-II scores (P < 0.001). The intervention group significantly reduced depressive symptoms from T0 to T1 (P < 0.001) and maintained lower levels at T2 (P < 0.001), whereas the control group showed minimal change at T1 (P = 0.08) and a slight increase at T2 (P > 0.05), as determined by Bonferroni-corrected post hoc tests. Between-group differences were significant at T1 and T2 (both P < 0.001). Gender moderated outcomes, with females showing greater reduction in depressive symptoms (P = 0.02). Marital status moderated effects, with married participants showing larger reductions (P = 0.04) (Table 3 and Figure 2).

4.5. Linear Mixed-Effects Model Analysis

A LMM using the lme4 package in R confirmed the ANOVA findings. The model included fixed effects for time (T0, T1, T2), group (intervention vs. control), time-by-group interaction, and covariates (gender, marital status), with participant-level random intercepts. For MSPSS, the time-by-group interaction was significant (P < 0.001), with the intervention group showing higher scores at T1 and T2 (P < 0.001). For BDI-II, the interaction was also significant (P < 0.001), with the intervention group showing lower scores at T1 and T2 (P < 0.001). Females (P = 0.03 for MSPSS; P = 0.02 for BDI-II) and married participants (P = 0.04 for both outcomes) showed greater improvements. Random effects were significant for both MSPSS and BDI-II (P < 0.001). Fixed effects are presented in Table 4.

| Outcomes and Predictors | Estimate | SE | t | P-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MSPSS | ||||

| Intercept (control, T0) | 46.10 | 1.45 | 31.79 | < 0.001 |

| Time: T1 (vs. T0) | -3.80 | 1.62 | -2.35 | 0.02 |

| Time: T2 (vs. T0) | -5.20 | 1.62 | -3.21 | 0.002 |

| Group: Intervention (vs. control) | -2.40 | 2.05 | -1.17 | 0.24 |

| Time: T1 × intervention | 9.60 | 2.29 | 4.19 | < 0.001 |

| Time: T2 × intervention | 7.30 | 2.29 | 3.19 | 0.002 |

| Gender: Female (vs. male) | 2.10 | 0.95 | 2.21 | 0.03 |

| Marital status: Married (vs. single) | 1.80 | 0.90 | 2.00 | 0.04 |

| BDI-II | ||||

| Intercept (control, T0) | 21.90 | 0.78 | 28.08 | < 0.001 |

| Time: T1 (vs. T0) | -1.60 | 0.85 | -1.88 | 0.06 |

| Time: T2 (vs. T0) | 0.80 | 0.85 | 0.94 | 0.35 |

| Group: Intervention (vs. control) | 1.90 | 1.10 | 1.73 | 0.09 |

| Time: T1 × intervention | -10.10 | 1.20 | -8.42 | < 0.001 |

| Time: T2 × intervention | -8.30 | 1.20 | -6.92 | < 0.001 |

| Gender: Female (vs. male) | -1.50 | 0.50 | -3.00 | 0.02 |

| Marital status: Married (vs. single) | -1.30 | 0.48 | -2.71 | 0.04 |

Abbreviations: SE, standard error; MSPSS, Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support; BDI-II, Beck Depression Inventory-II; T0, baseline; T1, post-intervention; T2, two-month follow-up.

a Estimates reflect fixed effects from the linear mixed-effects model with participant-level random intercepts.

5. Discussion

This RCT demonstrated that a 10-week IPT intervention significantly improved MSPSS and reduced BDI-II scores in adults with T2DM compared to standard care. The intervention group showed significant increases in MSPSS scores from T0 to T1 and maintained these gains at T2, while the control group’s scores declined. Similarly, BDI-II scores decreased substantially in the intervention group from T0 to T1 and remained lower at T2, whereas the control group showed minimal or negative changes. The significant time-by-group interactions and large effect sizes underscore IPT’s efficacy in addressing psychosocial challenges in T2DM. These findings align with IPT’s theoretical framework, which posits that resolving interpersonal stressors — grief, role disputes, role transitions, and interpersonal deficits — enhances social support and mitigates depression (10).

Consistent studies reinforce these results. A meta-analysis found IPT effective for depression in patients with medical comorbidities, reporting effect sizes for depressive symptom reduction similar to this study’s BDI-II outcomes. This meta-analysis included studies with varying IPT protocols, typically ranging from 8 to 16 sessions, with some focusing on general depression rather than T2DM-specific interpersonal issues, unlike our 10-session, T2DM-tailored intervention (26). Another study demonstrated IPT’s efficacy in improving social support and psychological well-being in patients with chronic illnesses like HIV, where interpersonal challenges parallel those in T2DM, such as stigma and caregiving conflicts. That study used a 12-session IPT protocol addressing HIV-related interpersonal stressors, differing slightly from our 10-session intervention tailored to T2DM-specific issues like dietary adherence conflicts (27).

The increase in MSPSS scores aligns with research showing that interventions targeting interpersonal relationships enhance perceived support in T2DM patients, which correlates with better self-care behaviors, self-care, and quality of life. This study employed a group-based interpersonal intervention over 8 sessions, less focused on addressing T2DM-specific interpersonal issues compared to our group-based IPT approach delivered over 10 sessions tailored for T2DM patients (28). The moderation effects of gender and marital status, with females and married participants showing greater improvements, are consistent with evidence that females and those with stronger relational networks respond more robustly to interpersonal therapies due to higher social sensitivity and support availability. This evidence was based on various interpersonal interventions, not always IPT-specific, with session numbers varying widely, unlike our standardized 10-session protocol (29). A review study in T2DM patients further supports this, noting that married individuals leverage social support more effectively to cope with chronic illness demands, enhancing psychological outcomes (30).

However, inconsistent findings in the literature highlight contextual differences. One study found that CBT outperformed IPT in improving glycemic control in T2DM patients with depression, suggesting CBT’s focus on cognitive restructuring and behavioral activation may better address self-management behaviors directly tied to physiological outcomes (31). The IPT’s emphasis on interpersonal dynamics may prioritize psychological over physiological benefits, as no significant physiological changes were assessed in this study. Another trial reported no significant improvement in social support following IPT in a general depressed population without chronic illness (32), possibly due to the absence of disease-specific interpersonal stressors or differences in delivery (e.g., group-based IPT). These discrepancies emphasize the need for T2DM-specific adaptations, as implemented in this study through tailored modules addressing conflicts over dietary adherence, grief over health losses, and role transitions post-diagnosis.

The sustained improvements in MSPSS and BDI-II at T2 suggest IPT fosters durable changes in interpersonal functioning, likely through enhanced communication skills, conflict resolution strategies, and strengthened social networks. For T2DM patients, resolving role disputes (e.g., family expectations around dietary compliance) or navigating role transitions (e.g., lifestyle adjustments) likely bolstered perceived support, reducing psychological distress (33). The lack of improvement in the control group underscores standard care’s inadequacy for addressing T2DM’s psychosocial burden, as routine medical visits often overlook mental health needs. The LMM analysis further clarifies that the time-by-intervention interaction drove significant outcomes, with gender and marital status amplifying effects, possibly due to females’ greater interpersonal engagement and married individuals’ access to supportive spouses.

These findings advocate for integrating IPT into T2DM care, particularly for patients with depressive symptoms or interpersonal challenges. Additional considerations include IPT’s potential mechanisms of change. By targeting interpersonal stressors outlined in the interpersonal theory, IPT may reduce depression by enhancing patients’ ability to seek and utilize social resources, which are critical for coping with T2DM’s chronic demands (34). The intervention group’s psychoeducational component, which linked interpersonal functioning to T2DM self-management, likely reinforced these benefits by empowering patients to negotiate support from family or peers. However, the absence of data on self-care behaviors (e.g., medication adherence, dietary compliance) or physiological markers limits understanding of IPT’s broader impact. Future studies should explore these pathways, examining whether improved social support mediates better self-care outcomes or if reduced depression directly enhances T2DM management. Cross-cultural validation is also warranted, as interpersonal dynamics and social support structures vary globally, potentially influencing IPT’s efficacy in diverse T2DM populations.

Implementing IPT in T2DM care faces practical barriers that warrant consideration. Therapist training costs can be substantial, requiring specialized programs to certify clinicians in IPT delivery, which may limit scalability in resource-constrained settings like low-income regions. Accessibility challenges, such as patients’ ability to attend in-person sessions due to mobility or time constraints, could hinder uptake. Our study’s use of telehealth options mitigated some accessibility issues, but infrastructure limitations in certain areas may restrict this approach. To enhance scalability, brief IPT training modules or group-based formats could be developed, and telehealth platforms should be prioritized to improve access, particularly for rural or underserved T2DM populations.

5.1. Conclusions

This RCT demonstrated that a 10-week IPT intervention significantly enhanced perceived social support and reduced depressive symptoms in adults with T2DM, with effects sustained at T2. Compared to standard care, IPT led to substantial improvements in MSPSS and BDI-II scores, with moderate to large effect sizes. These findings highlight IPT’s efficacy in addressing interpersonal stressors relevant to T2DM, such as role disputes and transitions, which contribute to psychological distress. Gender and marital status moderated outcomes, with females and married participants showing greater benefits, suggesting that relational factors influence IPT’s effectiveness. Based on these results, healthcare providers should consider integrating IPT into T2DM management protocols to address the psychological burden of the disease. Policymakers should prioritize training programs to increase the availability of IPT-trained therapists, particularly in underserved regions. Future research should explore IPT’s impact on physiological outcomes, such as glycemic control, and evaluate its cost-effectiveness and scalability in diverse settings. Long-term follow-up studies are needed to assess the durability of IPT’s effects and its potential to improve overall T2DM outcomes. By fostering interdisciplinary collaboration between mental health and diabetes care teams, IPT can contribute to a holistic approach to T2DM management, enhancing both psychological well-being and quality of life.

5.2. Limitations

This study provides valuable insights into the efficacy of IPT for adults with T2DM, but opportunities exist to further enhance its applicability. The sample size (n = 110) was sufficient to detect significant effects, yet expanding the sample in future studies could strengthen the generalizability of findings across diverse T2DM populations, including those in low- and middle-income countries with unique healthcare and cultural contexts. The intervention was delivered by highly trained, certified IPT therapists, ensuring fidelity and quality, which highlights an opportunity to explore scalable training models to make IPT more accessible in real-world settings with varying resource levels. While the study focused on psychological outcomes, such as perceived social support and depressive symptoms, future research could incorporate physiological measures, like glycemic control (e.g., HbA1c), to provide a more comprehensive understanding of IPT’s impact on T2DM management. The low attrition rate (5.45%) reflects strong participant engagement, and the use of ITT analysis with multiple imputation minimized potential bias, suggesting robust study design; however, further refinements could eliminate even minimal bias. Finally, the T2 demonstrated sustained effects, paving the way for longer-term studies to confirm the enduring benefits of IPT and its potential to transform T2DM care.