1. Background

Nursing is grounded in acquiring specialized scientific knowledge and practical skills, and integrating professional attitudes and values reflected in clinical practice and interpersonal interactions (1). At its core, the nursing profession revolves around the concept of care, which serves as its driving force and defining characteristic. One of the most essential approaches in pediatric nursing is family-centered care (FCC) (2). The FCC emphasizes collaboration between healthcare providers and the families of pediatric patients, grounded in systemic theory, recognizing both the child and the family as integral recipients of care (3, 4). The Institute for Family-Centered Care defines this approach as achieving an active partnership among the child, their family, and healthcare professionals (5).

Implementing FCC necessitates a fundamental shift in the perspectives, behaviors, and understanding of healthcare providers. According to the American Academy of Pediatrics, FCC is anchored in four core principles: Respect, information sharing, participation, and collaboration; these principles enable healthcare teams to address not only the emotional but also the educational and clinical needs of children and their families (6-8). Notably, the benefits of FCC include reduced stress and anxiety for children and parents, shorter hospital stays, minimization of adverse outcomes, enhanced comfort and support, strengthened family resilience, and improved treatment and discharge planning adequacy (9-11).

Empirical evidence supports the positive outcomes of this approach. For instance, Aslan and Esmaeili reported that family involvement in the treatment process leads to better clinical outcomes, reduced mortality rates, higher satisfaction levels, improved adherence to therapeutic regimens, and decreased re-hospitalization among children (12). The concept of satisfaction with healthcare services was first articulated at Harvard University. It eventually evolved into a critical indicator of hospital performance in countries such as Canada, Australia, and the United Kingdom (13). Patient and parental satisfaction (PS) with medical and nursing care is a multidimensional construct typically conceived as the degree to which provided services meet or exceed expectations (14). Higher satisfaction is associated with a better understanding of health information, improved treatment adherence, and enhanced health outcomes — all central to pediatric nursing goals (15, 16). Moreover, when parents are satisfied with the care they receive, it fosters greater motivation among nurses and contributes to higher professional fulfillment (17).

The PS is an essential component of pediatric care quality, influencing both patient outcomes and the overall effectiveness of healthcare delivery. Increased PS is associated with faster recovery, shorter hospitalizations, lower healthcare costs, and enhanced satisfaction among healthcare professionals (18). A recent survey by Toivonen et al. demonstrated that implementing FCC principles substantially improved the quality of nursing care and satisfaction among nurses and parents (19).

Although FCC is internationally recognized as a fundamental dimension of pediatric nursing, empirical evidence regarding its direct relationship with PS remains scarce, particularly within the Iranian healthcare context. Most domestic and international studies have focused on describing FCC principles or assessing general perceptions rather than quantitatively evaluating its measurable outcomes, such as satisfaction among parents of hospitalized children. This gap in evidence limits the ability of practitioners and policymakers to design interventions that genuinely enhance family experiences in pediatric wards. Furthermore, clinical observations in Iranian hospitals reveal a persistent discrepancy between the theoretical emphasis on family engagement and its actual implementation in daily care practices.

2. Objectives

The present cross-sectional study primarily aimed to investigate the relationship between the importance of family involvement in nursing care and PS among parents of hospitalized children. It also seeks to identify factors that influence PS within the context of family-centered nursing. The findings will help clarify how family-centered approaches impact the quality and outcomes of pediatric nursing for both patients and their families.

3. Methods

3.1. Study Design and Setting

This cross-sectional study was registered and approved in August 2023 and completed in January 2025 at Bouali Specialized Pediatric Hospital, affiliated with Ardabil University of Medical Sciences, northwest Iran. The actual sampling was conducted over five months, from April to September 2024, focusing on the relationship between the perceived importance of family involvement in nursing care, PS, and related factors.

3.2. Study Population and Sampling

The target population consisted of all nurses (N = 200) and 160 parents of children hospitalized at BouAli Hospital, Ardabil, Iran. The nurse group comprised all eligible staff working during the study period in pediatric inpatient wards, the infectious diseases ward, pediatric intensive care units, the neonatal intensive care unit (NICU), the pediatric oncology ward, and the outpatient/emergency observation unit. Nurses were recruited through census sampling. The parent sample size (n = 160) was calculated following King et al. (20), assuming a 95% confidence level, 80% power, a minimum anticipated correlation between FCC and PS of r = 0.23, and a 10% attrition rate. Parents were selected via proportional stratified random sampling from the same wards.

3.2.1. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria for Nurses

Nurses were eligible if they had (1) At least one year of work experience in pediatric departments; (2) held a bachelor’s degree in nursing; (3) were in good general physical and psychological health as self-reported; (4) provided written informed consent; and (5) completed the study questionnaire in full. Incomplete completion, defined as leaving more than 10% of items unanswered, was considered an exclusion criterion.

3.2.2. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria for Parents

Parents were eligible if they were (1) The mother or a female legal guardian of a hospitalized child; (2) had a child hospitalized in a pediatric ward for at least 24 hours; (3) demonstrated sufficient understanding to complete the questionnaire; (4) provided written informed consent; and (5) completed the questionnaire in full. Questionnaires with over 10% missing responses were excluded from the analysis.

3.3. Research Instruments

3.3.1. Demographic Information

A) Nurses’ demographic and social characteristics: Gender, marital status, age, educational level, work experience, and shift type.

B) Parents’ demographic and social characteristics: Including the child’s gender, age, duration of hospitalization, mother’s age, job, socioeconomic and educational level.

3.3.2. Families’ Importance in Nursing Care-Nurses’ Attitudes

The Families’ Importance in Nursing Care-Nurses’ Attitudes (FINC-NA) Questionnaire, developed initially by Benzein et al. (21) and later translated and psychometrically validated in Dutch by Hagedoorn et al. (22), was designed to measure nurses’ and parents’ perceptions regarding the importance of family involvement in nursing care. The instrument consists of 26 Likert-type items with five response options (scored 1 - 5), yielding a total score range of 26 - 130. In line with Bloom’s cut-offs (23), mean scores were categorized as low (15 - 59), moderate (60 - 79), or high (80 - 100), with higher scores indicating a stronger perceived importance of family involvement. The questionnaire covers four conceptual dimensions: (1) Family as a resource in nursing care (Fam-RNC); (2) family as a conversational partner (Fam-CP); (3) family as a burden (reverse scored to reflect positive attitudes); and (4) family as its own resource. By integrating both facilitative and potentially challenging aspects of family presence, the scale captures a multidimensional view of “perceived importance”, aligning measurement with the construct of interest. The original instrument demonstrated high reliability (Cronbach’s α = 0.88) (21). In the present study, content validity ratio (CVR = 0.85) and Content Validity Index (CVI = 0.87) were established. Internal consistency reliability was confirmed (Cronbach’s α = 0.89).

3.3.3. Parental Satisfaction and Its Associated Factors

The Empowerment of Parents in The Intensive Care-Neonatology (EMPATHIC-N) Questionnaire, developed and validated by Latour et al. (24), was designed to assess parents’ satisfaction with services in the NICU. The instrument consists of 57 Likert-type items distributed across five conceptual dimensions: (1) Information (12 items, 6-point scale); (2) care and treatment (17 items, 10-point scale); (3) parental participation (PP) (8 items, 6-point scale); (4) organization (8 items, 6-point scale); and (5) professional attitude (12 items, 6-point scale). Individual items are scored on a scale of 1 - 6 or 1 - 10, depending on their dimension. The total raw score ranges from 57 to 410. For interpretability, raw scores were converted into percentage scores using the formula:

Following Bloom’s classification (23), percentage scores were categorized as low (15 - 59%), moderate (60 - 79%), and high (80 - 100%), with higher scores indicating greater PS. By encompassing informational, emotional, organizational, and participatory aspects of NICU care, the instrument provides a multidimensional view of PS aligned with the construct of interest. The original EMPATHIC-N demonstrated high internal consistency, with Cronbach’s α ranging from 0.82 to 0.95 across dimensions (25). In the present study, content validity was established (CVR = 0.86, CVI = 0.89), and internal consistency reliability was confirmed (Cronbach’s α = 0.81).

3.4. Data Collection Procedure

In line with the inclusion criteria, only mothers present at the bedside of hospitalized children were enrolled as participants, reflecting their primary caregiving role during hospitalization. Coordination was undertaken with ward supervisors and head nurses to ensure minimal disruption to work routines across all three shifts (morning, afternoon, and night). Before distributing the questionnaire, the study objectives, procedures, potential benefits, and the voluntary nature of participation were explained to each participant. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants before data collection. Confidentiality and anonymity were ensured by using coded questionnaires without personal identifiers; data were stored securely and accessed only by the research team for analysis. Participants were informed of their right to withdraw from the study at any stage without any consequences.

3.5. Data Analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS version 24.0. Continuous variables were summarized as mean and standard deviation (SD), while categorical variables were presented as frequencies and percentages. The normality of data distributions was assessed using the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test (P < 0.05). To examine the relationships between the socio-demographic characteristics of nurses, the importance of family in nursing care, and PS, one-sample t-tests, independent t-tests, and one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) were employed. The Pearson correlation coefficient and simple linear regression analyses were also conducted to assess the association between the family’s importance in nursing care and PS. A two-sided P-value less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

4. Results

A total of 200 nurses participated in the study. The majority were female (190; 95%) and married (157; 78.5%). Most of the nurses held a BSc degree (185; 92.5%). The mean age of nurses was 32.8 years (SD = 7.11), and their average work experience was 9.0 years (SD = 3.42). Regarding work shifts, 111 nurses (55.5%) worked rotating (circular) shifts, 46 (23.0%) worked morning shifts, 23 (11.5%) worked evening shifts, and 20 (10.0%) worked night shifts.

Among the parents surveyed, 108 (54.4%) of the children were boys. Concerning mothers’ educational attainment, 109 (54.4%) held a high school diploma, 53 (26.3%) had a regular diploma, 35 (17.5%) had a bachelor’s degree, and 4 (1.9%) held a PhD. The mean age of hospitalized children was 5.4 years (SD = 2.75), with an average hospitalization length of 5.1 days (SD = 2.04). Regarding birth order, 83 (41.3%) of the children were firstborn, 76 (38.1%) were secondborn, and 38 (18.8%) were thirdborn.

No statistically significant differences were found between FINC-NA scores and demographic factors among nurses, or between PS and demographic or clinical variables among parents and children (P > 0.05) (Table 1). Regarding perceptions of the importance of families in nursing care, 90% of nurses rated this aspect as middle-level, 7.5% rated it as good, and 2.5% rated it as weak. The mean perceived importance score was 88.19 ± 5.67. Across subcomponents, the highest mean was observed for family as a resource (35.31 ± 4.84), followed by Fam-CP (29.51 ± 4.51), Fam-RNC (22.40 ± 3.28), and family as a burden (22.33 ± 3.74).

| Variables | No. (%) | P-Value |

|---|---|---|

| Nurses | ||

| Gender | 0.771 a | |

| Male | 10 (5) | |

| Female | 190 (95) | |

| Marital status | 0.181 a | |

| Single | 43 (21.5) | |

| Married | 157 (78.5) | |

| Education | 0.053 a | |

| BSc | 185 (92.5) | |

| MSc | 15 (7.5) | |

| Shift work | 0.649 a | |

| Morning | 46 (23) | |

| Evening | 23 (11.5) | |

| Night | 20 (10) | |

| Circular shift | 111 (55.5) | |

| Age (y) | 32.78 (7.11) | 0.544 a |

| Work experience (y) | 8.95 (3.42) | 0.332 a |

| Parents | ||

| Gender | 0.656 b | |

| Boy | 87 (54.4) | |

| Girl | 73 (45.6) | |

| Mother’s job | 0.764 b | |

| Employed | 18 (11.3) | |

| Housewife | 142 (88.7) | |

| Mother’s education level | 0.197 b | |

| High school | 87 (54.4) | |

| Diploma | 42 (26.3) | |

| Bachelor | 28 (17.5) | |

| PhD | 3 (1.9) | |

| Families socioeconomic | 0.868 b | |

| Weak | 26 (16.3) | |

| Moderate | 100 (62.5) | |

| Good | 34 (21.3) | |

| The number of children in the family | 0.115 b | |

| First | 66 (41.3) | |

| Second | 61 (38.1) | |

| Third | 30 (18.8) | |

| Others | 3 (1.9) | |

| Children’s age (y) | 5.4 (2.75) | 0.062 b |

| Duration of hospitalization (d) | 5.14 (2.04) | 0.723 b |

a Families’ Importance in Nursing Care-Nurses’ Attitudes Questionnaire.

b Parental Satisfaction and Its Associated Factors Questionnaire.

Regarding PS, 95% of respondents reported a middle level of satisfaction, and 5% reported a high level of satisfaction. The overall PS score was 300.81 ± 11.94. Among subcomponents, the highest mean scores were for care and treatment (131.00 ± 5.05) and PP (131.00 ± 5.05), followed by professional attitude (55.15 ± 3.02), information (45.85 ± 4.95), and organization (30.98 ± 2.46) (Table 2).

| Variables and Interpretation | No. (%) | Mean ± SD |

|---|---|---|

| The importance of families in nursing care | ||

| Weak | 5 (2.5) | |

| Middle | 180 (90) | 88.19 ± 5.67 |

| Good | 15 (7.5) | |

| Subcomponents | ||

| Fam-OR | 35.31 ± 4.84 | |

| Fam-CP | 29.51 ± 4.51 | |

| Fam-RNC | 22.4 ± 3.28 | |

| Fam-B | 22.33 ± 3.74 | |

| PS | ||

| Weak | - | |

| Middle | 152 (95) | 300.81 ± 11.94 |

| Well | 8 (5) | |

| Subcomponents | ||

| I | 45.85 ± 4.95 | |

| CT | 131 ± 5.05 | |

| PP | 131 ± 5.05 | |

| O | 30.98 ± 2.46 | |

| PA | 55.15 ± 3.02 |

Abbreviations: Fam-OR, family as a resource; Fam-CP, family as a conversational partner; Fam-RNC, family as a resource in nursing care; Fam-B, family as a burden; PS, parental satisfaction; I, information; CT, care and treatment; PP, parental participation; O, organization; PA, professional attitude.

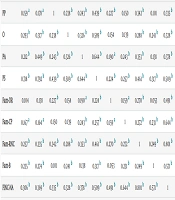

Table 3 presents the correlations between PS domains and the FINC-NA dimensions on the perceived importance of family in nursing care. The PS demonstrated its strongest associations with care and treatment (CT, r = 0.792, P < 0.01), information (I, r = 0.718, P < 0.01), and professional attitude (PA, r = 0.644, P < 0.01). The FINC-NA scores were most strongly correlated with Fam-RNC (r = 0.801, P < 0.01) and Fam-CP (r = 0.644, P < 0.01). Moderate positive correlations (r = 0.335 - 0.509, all P < 0.01) were also found between PP, organization (O), and both PS and FINC-NA scores.

| Variables | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| I | 1 | 0.376 b | 0.159 a | 0.293 b | 0.212 b | 0.718 b | 0.104 | 0.167 a | 0.257 b | 0.235 b | 0.306 b |

| CT | 0.376 b | 1 | 0.178 a | 0.317 b | 0.449 b | 0.792 b | 0.138 | 0.164 a | 0.335 b | 0.274 b | 0.369 b |

| PP | 0.159 a | 0.178 a | 1 | 0.238 b | 0.243 b | 0.439 b | 0.227 b | 0.150 | 0.342 b | 0.101 | 0.335 b |

| O | 0.293 b | 0.317 b | 0.238 b | 1 | 0.326 b | 0.589 b | 0.154 | 0.139 | 0.288 b | 0.241 b | 0.328 b |

| PA | 0.212 b | 0.449 b | 0.243 b | 0.326 b | 1 | 0.644 b | 0.190 a | 0.243 b | 0.353 b | 0.138 | 0.378 b |

| PS | 0.718 b | 0.792 b | 0.439 b | 0.589 b | 0.644 b | 1 | 0.224 b | 0.257 b | 0.461 b | 0.317 b | 0.509 b |

| Fam-OR | 0.104 | 0.138 | 0.227 b | 0.154 | 0.190 a | 0.224 b | 1 | 0.159 a | 0.270 b | 0.053 | 0.491 b |

| Fam-CP | 0.167 a | 0.164 a | 0.150 | 0.139 | 0.243 b | 0.257 b | 0.159 a | 1 | 0.272 b | 0.231 b | 0.644 b |

| Fam-RNC | 0.257 b | 0.335 b | 0.342 b | 0.288 b | 0.353 b | 0.461 b | 0.270 b | 0.272 b | 1 | 0.249 b | 0.801 b |

| Fam-B | 0.235 b | 0.274 b | 0.101 | 0.241 b | 0.138 | 0.317 b | 0.053 | 0.231 b | 0.249 b | 1 | 0.571 b |

| FINC-NA | 0.306 b | 0.369 b | 0.335 b | 0.328 b | 0.378 b | 0.509 b | 0.491 b | 0.644 b | 0.801 b | 0.571 b | 1 |

Abbreviations: I, information; CT, care and treatment; PP, parental participation; O, organization; PA, professional attitude; PS, parental satisfaction; Fam-OR, family as a resource; Fam-CP, family as a conversational partner; Fam-RNC, family as a resource in nursing care; Fam-B, family as a burden; FINC-NA, families’ importance in nursing care-nurses’ attitudes.

a Correlation is significant at the 0.01 level (2-tailed).

b Correlation is Significant at the 0.05 level (2-tailed).

In Table 4, multiple regression analysis was conducted to identify significant predictors of PS among participants. Among the examined subscales of the “Family Importance in Nursing Care” (FINC-NA) instrument, both the “Family as Resource in Nursing Care” (Fam-RNC) (β = 0.366, P < 0.001) and the “Family as a Burden” (Fam-B) (β = 0.199, P = 0.006) subcomponents were found to be significant predictors of PS. Specifically, higher scores in the Fam-RNC dimension were positively and significantly associated with PS, while perceptions aligning with the Fam-B dimension also showed a significant positive relationship. In contrast, the “Family as an Own Resource” (Fam-OR) (β = 0.085, P = 0.234) and “Family as Conversational Partner” (Fam-CP) (β = 0.090, P = 0.217) subscales were not significantly associated with PS in the regression model. The overall model explained 27.4% of the variance in PS (R2 = 0.274, F = 14.62, P < 0.001), indicating a moderate effect size. The Durbin-Watson statistic was 1.39, indicating no significant concerns regarding autocorrelation among the residuals.

| Predictor Variables | R | Unstandardized β Coefficient | SE | Standardized β Coefficient | t | P-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fam-OR | 0.224 | 0.686 | 0.575 | 0.085 | 1.194 | 0.234 |

| Fam-CP | 0.257 | 0.501 | 0.404 | 0.09 | 1.240 | 0.217 |

| Fam-RNC | 0.461 | 1.38 | 0.282 | 0.366 | 4.915 | < 0.001 |

| Fam-B | 0.317 | 1.277 | 0.461 | 0.199 | 2.772 | 0.006 |

| Model characteristics | R2 = 0.274; Adj R2 = 0.255; F = 14.62; P < 0.001; DW = 1.39 | |||||

Abbreviations: Fam-OR, family as a resource; Fam-CP, family as a conversational partner; Fam-RNC, family as a resource in nursing care; Fam-B, family as a burden; DW, Durbin-Watson test.

5. Discussion

This study explored how nurses in northwest Iran perceive the family’s role in nursing care and how these perceptions relate to PS during pediatric hospitalization. The findings revealed a moderate level of appreciation for family involvement among nurses, mirroring outcomes reported by Abdel Razeq et al. (26), Seniwati et al. (27), and Dehghani et al. (28). Such cross-study consistency signals a persistent mid-range internalization of FCC principles within low and middle-income health systems. Shared challenges, including limited workforce capacity, uneven FCC training, and inconsistent institutional endorsement, likely constrain nurses’ ability to translate supportive attitudes into consistent bedside practice. In many Iranian hospitals, nurses simultaneously shoulder technical, administrative, and emotional workloads, which inherently limit the time available for collaborative decision-making with families.

Conversely, studies conducted in better-resourced and policy-aligned settings, such as those by Lim and Bang (29) and Done et al. (30), demonstrate higher ratings of the perceived importance of family participation. These systems typically embed FCC into national nursing curricula, provide ongoing reflective training, and formalize guidelines that articulate families’ rights and responsibilities. The contrast underscores how structural support, not merely awareness, determines whether positive beliefs mature into sustained practice. Hence, the divergence between Iranian and international findings may reflect varying stages of FCC institutionalization, with Iran positioned in an intermediate phase of policy translation.

In this study, PS also fell within a moderate range, paralleling findings from Fuadah et al. (31), Xenodoxidou et al. (32), Kruszecka-Krowka et al. (33), and Umoke et al. (34). This convergence suggests that parental perceptions may be universally sensitive to communication quality and relational continuity rather than solely to structural resources. However, the comparatively higher satisfaction reported by Tsironi and Koulierakis (35) in contexts with legally protected PP rights indicates that systemic legitimization of family involvement amplifies satisfaction through psychological safety and trust. Iranian hospitals, by contrast, remain guided primarily by physician-led hierarchies, where parental input is valued informally but seldom codified through institutional policy.

A noteworthy contribution of the present study is its dual portrayal of the family as both a resource and, paradoxically, a burden, each showing positive associations with satisfaction. This pattern suggests that even when nurses perceive family interactions as demanding, the very process of engagement fosters parental trust and comfort. Culturally, Iranian families often prioritize involvement and advocacy for their hospitalized child, and nurses’ pragmatic engagement with this expectation, despite its workload costs, may inadvertently enhance parents’ sense of inclusion. This context-specific nuance highlights that emotional labor and relational negotiation are integral, not peripheral, components of FCC.

Unlike earlier evidence from Wu et al. (36), Malfait et al. (37), and Okunola et al. (38), this study did not observe a significant correlation between work experience and FCC attitudes. The absence of this relationship may reflect systemic gaps in ongoing professional development. Whereas FCC refresher programs are standard in many western settings, Iranian hospitals lack consistent continuing education in partnership-based models. Experience alone, therefore, does not strengthen FCC orientation unless coupled with institutional reinforcement and reflective training structures.

Overall, these findings emphasize that attitudinal transformation alone is insufficient without organizational scaffolding that normalizes family participation. Embedding FCC into performance assessments, clinical guidelines, and interprofessional education could bridge the gap between conceptual endorsement and operational enactment. This research, the first of its kind in Iran’s pediatric nursing domain, enriches the limited national discourse on FCC by quantitatively linking nurses’ perceptions with parental outcomes, a connection previously theorized but rarely demonstrated empirically.

5.1. Conclusions

The findings demonstrated moderate levels of family importance and PS. Regression analysis identified “Family as a Resource in Nursing Care” as the strongest predictor of PS among the evaluated dimensions. These results highlight the pivotal role of family inclusion in nursing practice and underscore the need for healthcare policymakers and administrators to prioritize strategies that enhance FCC in pediatric settings. Implementing structured family engagement interventions and providing ongoing support for nurses may improve the quality of care and parent satisfaction. Further research, particularly longitudinal and multi-center studies, is recommended to understand the long-term effects of FCC interventions and develop evidence-based approaches for sustaining PS in diverse hospital contexts.

5.2. Implications

The findings highlight the need for continuous professional development that places family inclusion at the core of pediatric nursing. Healthcare institutions should implement culturally sensitive approaches and routinely evaluate family support systems through parental feedback to strengthen care quality. In education, FCC principles must be integrated into nursing curricula through experiential and interprofessional learning, enabling students to develop communication, empathy, and partnership skills essential for effective family engagement. In research, longitudinal and intervention studies are needed to clarify causal relationships between FCC attitudes and PS, while qualitative designs can explore contextual and cultural factors influencing these dynamics. Together, these steps can foster a lasting culture of collaboration and ensure that FCC becomes an embedded element of pediatric nursing practice.