1. Background

The hospital environment is inherently demanding, characterized by high workloads, rapid clinical changes, and emotionally challenging events such as patient mortality (1). Nursing, especially in intensive care units (ICUs), is among the most stressful healthcare professions, exposing staff to both physical and psychological strain. These pressures reduce job satisfaction, raise absenteeism and turnover, and compromise the quality of patient care (2). In ICUs, the risk of burnout is heightened by exposure to life-threatening situations, complex decision-making, and constant contact with critically ill patients (3). Burnout manifests as emotional exhaustion, depersonalization, and reduced personal accomplishment (4). Emotional exhaustion has been linked to depression, anxiety, reduced performance, and ethical lapses (5). A meta-analysis reported prevalence rates of emotional exhaustion, depersonalization, and reduced accomplishment among nurses as 31%, 36%, and 29%, respectively (6).

Promoting positive psychological indicators is equally vital in critical care nursing. Resilience — the capacity to recover from adversity — supports adaptation, emotional regulation, and sustained performance (7). Professional ethics, encompassing respect for autonomy, confidentiality, justice, empathy, and commitment to care, underpins high-quality, patient-centered services (8). Greater resilience and strong ethics are associated with improved outcomes, teamwork, and job satisfaction (9), whereas impaired psychological resources undermine ethical practice (10).

Organizational factors, particularly leadership styles, play a pivotal role in shaping these indicators (11). Supportive and participative leadership enhances resilience, ethics, and stress management, while authoritarian or task-oriented styles may exacerbate burnout (12).

Although evidence links leadership to nursing outcomes, most studies examine resilience, ethics, or emotional well-being in isolation (13). Few address these dimensions concurrently in ICUs, where the interplay between leadership and psychological factors is most critical (10, 12). Furthermore, much of the research is conducted outside Iran, reducing its local applicability. Addressing this gap, the present study investigates associations between leadership styles and resilience, professional ethics, and emotional exhaustion among ICU nurses in Iranian teaching hospitals. By exploring these links, this study aims to provide evidence that may guide future research in designing and evaluating targeted interventions to enhance nurses’ psychological well-being, strengthen professional ethics, and improve patient care quality and safety.

2. Objectives

The objective was to determine the relationship between leadership styles and psychological job indicators — resilience, professional ethics, and emotional exhaustion — among ICU nurses.

3. Methods

This descriptive–analytical cross-sectional study was conducted in 2024 in ICUs of three teaching hospitals affiliated with Lorestan University of Medical Sciences, Iran. The study population included all registered ICU nurses, using census sampling. Of 250 eligible nurses, 215 completed the questionnaires. The sample size (N = 215) exceeded methodological standards. For multivariate regression, guidelines suggest 130 - 160 participants for up to 10 predictors, while power analyses for small-to-moderate effects (R = 0.20; f2 = 0.08 - 0.10) require 190 - 200 participants at 80% power (14). Therefore, our final sample provided sufficient statistical power and precision for the planned analyses.

Eligibility criteria included active employment in an ICU, possession of an associate degree or higher in nursing, at least three years of ICU work experience, residency in Lorestan province, fitness for regular duty at the time of the survey, and provision of informed consent. Nurses who reported chronic physical or mental illnesses (e.g., diabetes, depression) or who were unwilling to continue participation at any stage were excluded from the study.

Ethical approval for the study was obtained from the Ethics Committee of Lorestan University of Medical Sciences (IR.LUMS.REC.1402.237). Participants were assured of confidentiality and informed of their voluntary participation, with the right to withdraw at any time without penalty. Written informed consent was obtained prior to data collection. Data were collected using a demographic questionnaire and four standardized instruments. The demographic form captured gender, age, marital status, education, ICU experience, job position, tobacco use, and income.

Leadership styles were measured with the Hersey and Blanchard Questionnaire (1979), comprising 12 situational items with four options reflecting directive, coaching, supportive, and delegating styles; summed scores identified the dominant style (15). Its validity and reliability in Iranian nursing populations are confirmed, with Cronbach’s alpha 0.81 and Content Validity Index above 0.79 (16).

Professional ethics were assessed with the 16-item Caduzier Questionnaire covering eight dimensions, rated on a five-point Likert scale; higher scores indicate stronger adherence (17). The validated Persian version, widely used in Iran, shows acceptable validity and reliability with Cronbach’s alpha 0.81 - 0.85 (18, 19). Resilience was measured with the 25-item Connor-Davidson Resilience Scale (CD-RISC), scored 0 - 4, total 0 - 100; higher scores indicate greater resilience (20). The Persian CD-RISC, validated through translation and psychometric testing, shows strong reliability (Cronbach’s α ≈ 0.90) (21).

Emotional exhaustion was assessed using the nine-item Maslach Burnout Inventory subscale, rated on a five-point Likert scale, total 9 - 45, categorized as low (< 16), moderate (17 - 26), or high (> 27) (22). This subscale demonstrates reliability coefficients between 0.70 - 0.92 in Iranian studies (9, 23).

Data collection was conducted electronically via Google Forms. Links were distributed by ICU head nurses and supervisors through professional groups. Participants completed questionnaires after receiving study explanations. Form settings restricted submissions to one response per Google account, ensuring each participant could submit only once and preventing duplicate or incomplete entries.

Data were analyzed using SPSS 25. Normality of continuous variables was tested with the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test. Descriptive statistics (means, SDs, frequencies) were computed. Inferential analyses included t-tests, one-way ANOVA, Pearson correlations, and multivariable regressions adjusted for demographics. Resilience, ethics, and exhaustion were dependent variables, with leadership style (dominant Hersey-Blanchard category) as predictor. Sensitivity analyses modeled continuous leadership scores as dependent, with psychological indicators as predictors. Statistical significance was defined as P < 0.05 for all tests.

4. Results

Of the 250 ICU nurses invited, 215 completed the questionnaire (response rate = 86%). The Kolmogorov-Smirnov test confirmed normal distribution of continuous variables (P > 0.05). Demographic and occupational characteristics are summarized in Table 1.

| Variables | No. (%) | Leadership Style | Professional Ethics | Resilience | Emotional Exhaustion |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | |||||

| Female | 140 (62.2) | 26.83 ± 4.06 | 63.13 ± 4.13 | 67.95 ± 8.69 | 27.96 ± 8.57 |

| Male | 75 (33.3) | 25.26 ± 2.86 | 63.16 ± 4.50 | 69.62 ± 10.03 | 26.20 ± 8.03 |

| P-value | - | 0.002 | 0.969 | 0.226 | 0.143 |

| Marital status | |||||

| Single | 60 (27.9) | 25.88 ± 3.73 | 62.43 ± 4.30 | 65.03 ± 11.08 | 27.28 ± 7.75 |

| Married | 146 (67.9) | 26.33 ± 3.79 | 63.42 ± 4.31 | 69.71 ± 7.94 | 27.16 ± 8.66 |

| Divorced | 9 (4.2) | 28.22 ± 2.95 | 63.33 ± 2.12 | 72.77 ± 8.63 | 30.77 ± 8.83 |

| P-value | - | 0.213 | 0.313 | 0.001 | 0.459 |

| Education level | |||||

| Associate | 1 (0.4) | 26.00 ± 0 | 62.00 ± 0 | 70.00 ± 0 | 30.00 ± 0 |

| Bachelor | 198 (88.0) | 26.21 ± 3.74 | 63.04 ± 4.30 | 68.24 ± 9.33 | 27.27 ± 8.32 |

| Master | 16 (7.1) | 27.25 ± 4.09 | 64.50 ± 3.58 | 72.06 ± 6.96 | 28.18 ± 9.93 |

| P-value | - | 0.570 | 0.405 | 0.278 | 0.872 |

| Job position | |||||

| Nurse | 207 (92.0) | 26.20 ± 3.72 | 63.05 ± 4.23 | 68.48 ± 9.28 | 27.40 ± 8.39 |

| Head nurse | 8 (3.6) | 28.37 ± 4.34 | 65.37 ± 4.40 | 70.00 ± 7.01 | 26.00 ± 9.36 |

| P-value | - | 0.110 | 0.131 | 0.648 | 0.645 |

| Hospital name | |||||

| Shahid Ashayer | 81 (37.7) | 26.14 ± 3.49 | 62.53 ± 4.48 | 67.07 ± 9.07 | 29.01 ± 7.54 |

| Shahid Rahimi | 73 (33.9) | 25.88 ± 3.09 | 62.82 ± 4.30 | 69.17 ± 6.49 | 22.74 ± 7.08 |

| Shahid Madani | 61 (28.4) | 27.09 ± 4.22 | 64.01 ± 3.62 | 69.40 ± 8.80 | 33.00 ± 6.49 |

| P-value | - | 0.169 | 0.091 | 0.021 | < 0.001 |

| Smoking | |||||

| Yes | 7 (3.3) | 27.86 ± 2.61 | 63.08 ± 4.27 | 69.14 ± 4.09 | 25.00 ± 9.03 |

| No | 208 (96.7) | 26.23 ± 3.79 | 65.00 ± 3.36 | 68.52 ± 9.33 | 27.42 ± 8.40 |

| P-value | - | 0.157 | 0.188 | 0.720 | 0.500 |

| Monthly income (Million IRR) | |||||

| < 10 (very low) | 28 (13.0) | 25.47 ± 3.65 | 61.92 ± 4.40 | 65.18 ± 9.20 | 30.82 ± 8.85 |

| 10 - 13 (low) | 74 (34.4) | 26.08 ± 3.73 | 62.88 ± 4.19 | 67.64 ± 8.76 | 28.53 ± 8.34 |

| 13 - 16 (almost low) | 61 (28.3) | 26.70 ± 3.81 | 63.69 ± 4.08 | 69.18 ± 8.29 | 26.41 ± 7.90 |

| 16 - 19 (medium) | 41 (19.1) | 27.10 ± 3.92 | 64.45 ± 3.92 | 70.56 ± 7.62 | 24.18 ± 6.93 |

| > 19 (high) | 11 (5.1) | 27.68 ± 4.12 | 64.92 ± 3.85 | 71.08 ± 7.38 | 23.10 ± 6.72 |

| P-value | - | 0.162 | 0.049 | 0.033 | 0.004 |

| Age (y) | 34.48 ± 7.03 | 0.085 ± 0.212 | 0.060 ± 0.381 | 0.088 ± 0.212 | 0.030 ± 0.666 |

| Work experience (y) | 9.70 ± 6.23 | 0.081 ± 0.237 | 0.142 ± 0.038 | 0.130 ± 0.057 | 0.026 ± 0.703 |

Abbreviation: IRR, Iranian rial.

a Values are expressed as mean ± SD unless indicated.

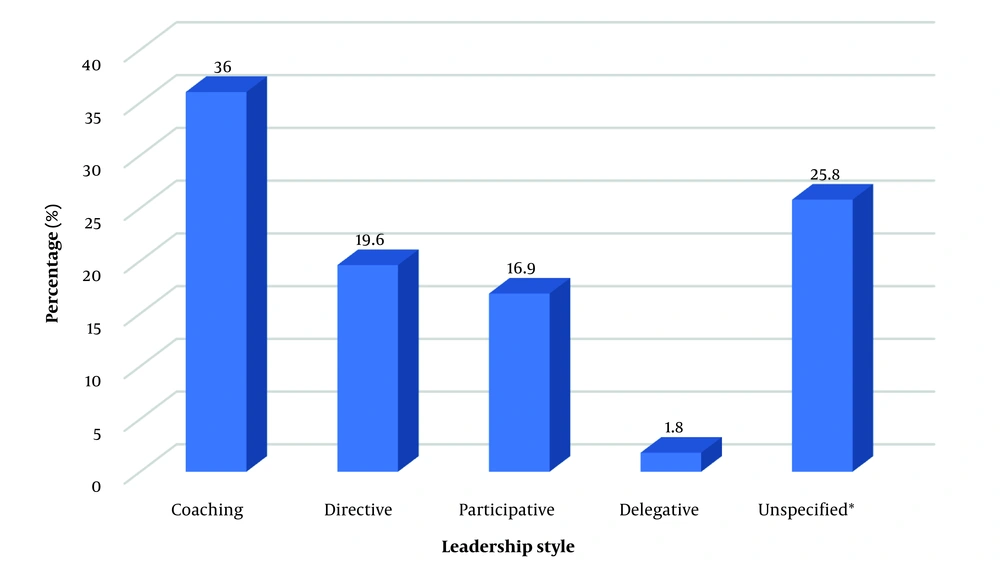

Coaching emerged as the predominant leadership style, followed by directive and participative types, whereas the delegative style was least common. The frequency of leadership styles is shown in Figure 1.

Bivariate analyses revealed significant associations between gender and leadership style (P = 0.002), marital status and resilience (P = 0.001), and workplace with both resilience (P = 0.021) and emotional exhaustion (P < 0.001). Nurses with chronic illness exhibited higher professional ethics scores (P = 0.031). Monthly income was significantly associated with professional ethics (P = 0.049), resilience (P = 0.033), and emotional exhaustion (P = 0.004). Correlation analyses showed positive relationships between work experience and professional ethics (R = 0.142, P = 0.038), and between income and emotional exhaustion (R = 0.192, P = 0.005).

Primary analyses showed that leadership style significantly predicted resilience and professional ethics, but not emotional exhaustion after covariate adjustment. Descriptive analyses indicated mean ± SD scores for the psychological job indicators as follows: Resilience = 68.6 ± 9.2, professional ethics = 63.1 ± 4.3, and emotional exhaustion = 27.3 ± 8.4. Categorical results were consistent with the continuous models, showing that coaching and participative leadership styles outperformed directive leadership. Detailed regression estimates are presented in Table 2.

| Outcomes (Dependent) and Predictors (Leadership Style) | Model 1 | Model 2 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unadjusted β (95% CI) | P-Value | Adjusted β (95% CI) | P-Value | |

| Resilience | ||||

| Continuous (per 1 SD) | 1.25 (0.55 - 1.94) | 0.001 | 1.08 (0.34 - 1.82) | 0.004 |

| Coaching vs. directive | +2.10 (0.85 - 3.45) | 0.001 | +1.74 (0.48 - 3.01) | 0.007 |

| Participative vs. directive | +1.61 (0.21 - 3.01) | 0.024 | +1.32 (0.06 - 2.57) | 0.041 |

| Delegative vs. directive | -0.39 (-2.35 - 1.57) | 0.693 | -0.28 (-2.21 - 1.66) | 0.782 |

| Unspecified vs. directive | +0.73 (-0.42 - 1.88) | 0.213 | +0.52 (-0.62 - 1.66) | 0.372 |

| Professional ethics | ||||

| Continuous (per 1 SD) | 0.58 (0.08 - 1.07) | 0.022 | 0.51 (0.04 - 0.98) | 0.034 |

| Coaching vs. directive | +0.92 (0.12 - 1.72) | 0.024 | +0.78 (0.01 - 1.55) | 0.048 |

| Participative vs. directive | +0.81 (0.03 - 1.58) | 0.042 | +0.69 (-0.05 - 1.43) | 0.068 |

| Delegative vs. directive | +0.18 (-1.15 - 1.51) | 0.792 | +0.09 (-1.16 - 1.34) | 0.890 |

| Unspecified vs. directive | +0.27 (-0.46 - 1.00) | 0.465 | +0.19 (-0.54 - 0.92) | 0.610 |

| Emotional exhaustion | ||||

| Continuous (per 1 SD) | -0.42 (-1.06 - 0.22) | 0.196 | -0.31 (-0.97 - 0.35) | 0.354 |

| Coaching vs. directive | -0.66 (-2.23 - 0.91) | 0.411 | -0.53 (-2.02 - 0.97) | 0.491 |

| Participative vs. directive | -0.49 (-2.19 - 1.21) | 0.572 | -0.37 (-2.08 - 1.34) | 0.671 |

| Delegative vs. directive | +0.43 (-1.88 - 2.74) | 0.710 | +0.52 (-1.79 - 2.83) | 0.659 |

| Unspecified vs. directive | +0.19 (-1.10 - 1.49) | 0.772 | +0.11 (-1.11 - 1.33) | 0.858 |

Analysis revealed significant links between leadership style, gender, marital status, and job position. Married nurses favored coaching, divorced nurses participative, and head nurses reported participative styles more than staff. No other associations emerged. Full cross-tabulations appear in Table 3.

| Variables | Coaching | Directive | Participative | Delegative | Unspecified | P-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age year | 34.06 ± 7.2 | 33.66 ± 6.4 | 36.10 ± 7.7 | 32.30 ± 5.5 | 34.80 ± 6.7 | 0.492 |

| Work experience year | 9.7 ± 6.4 | 8.4 ± 5.5 | 11.3 ± 7.1 | 7.0 ± 4.2 | 9.8 ± 5.8 | 0.297 |

| Gender | 0.049 | |||||

| Female | 55 (39.3) | 21 (15.0) | 28 (20.0) | 4 (2.9) | 32 (22.9) | |

| Male | 26 (34.7) | 23 (30.7) | 10 (13.3) | 0 (0.0) | 16 (21.3) | |

| Marital status | 0.009 | |||||

| Single | 22 (36.7) | 20 (33.3) | 6 (10.0) | 3 (5.0) | 9 (15.0) | |

| Married | 56 (38.4) | 24 (16.6) | 28 (19.2) | 1 (0.7) | 37 (25.3) | |

| Divorced | 3 (33.3) | 0 (0.0) | 4 (44.4) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (22.2) | |

| Education level | 0.259 | |||||

| Associate | 1 (1.2) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 4 (2.0) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Bachelor | 76 (38.4) | 41 (20.7) | 31 (15.7) | 0 (0.0) | 46 (23.2) | |

| Master | 4 (25.0) | 3 (18.8) | 7 (43.8) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (12.5) | |

| Job position | 0.017 | |||||

| Nurse | 79 (38.2) | 43 (20.8) | 33 (15.9) | 4 (1.9) | 48 (23.2) | |

| Head nurse | 2 (25.0) | 1 (12.5) | 5 (62.5) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Monthly income (Million IRR) | 0.154 | |||||

| < 10 (very low) | 16 (45.7) | 5 (14.3) | 9 (25.7) | 16 (45.7) | 3 (8.6) | |

| 10 - 13 (low) | 35 (45.5) | 13 (16.9) | 9 (11.7) | 35 (45.5) | 20 (26.0) | |

| 13 - 16 (almost low) | 15 (25.0) | 17 (28.3) | 10 (16.7) | 15 (25.0) | 17 (28.3) | |

| 16 - 19 (medium) | 10 (32.3) | 7 (22.6) | 7 (22.6) | 10 (32.3) | 7 (22.6) | |

| > 19 (high) | 4 (36.4) | 2 (18.2) | 3 (27.3) | 1 (9.1) | 1 (9.1) | |

| Hospital name | 0.056 | |||||

| Shahid Ashayer | 33 (46.5) | 14 (19.7) | 11 (15.5) | 2 (2.8) | 11 (15.5) | |

| Shahid Rahimi | 19 (28.4) | 19 (28.4) | 12 (17.9) | 0 (0.0) | 17 (25.4) | |

| Shahid Madani | 23 (41.8) | 6 (10.9) | 13 (23.6) | 2 (3.6) | 11 (20.0) | |

| Chronic illness | 0.292 | |||||

| Yes | 7 (50.0) | 0 (0.0) | 4 (28.6) | 0 (0.0) | 3 (21.4) | |

| No | 74 (36.8) | 44 (21.9) | 34 (16.9) | 4 (2.0) | 45 (22.4) | |

| Smoking | 0.903 | |||||

| Yes | 2 (28.6) | 1 (14.3) | 2 (28.6) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (28.6) | |

| No | 79 (38.0) | 43 (20.7) | 36 (17.4) | 4 (1.9) | 46 (22.1) |

a Values are expressed as mean ± SD or No. (%).

5. Discussion

This study aimed to assess the predictive role of leadership style in ICU nurses’ psychological job indicators — resilience, professional ethics, and emotional exhaustion. Leadership style significantly predicted greater resilience and stronger ethics, but no association remained with emotional exhaustion after covariate adjustment. Practically, leadership development emphasizing coaching and participative behaviors appears especially valuable for enhancing nurses’ adaptive capacity and ethical conduct in high-acuity ICU environments.

Our findings are consistent with literature that frames leadership as a proximal organizational determinant of psychological resources in clinical teams (24, 25). Coaching and participative styles — emphasizing support, empowerment, feedback, and shared decision-making — enhance self-efficacy, reflective practice, and value-based behaviors, aligning with improved resilience and professional ethics (24, 25). The absence of an association with emotional exhaustion after adjustment may reflect protective leadership norms, strong team climate, or the influence of distal stressors (e.g., workload, staffing) beyond leadership’s direct impact (26). The attenuation after adjustment suggests partial confounding by demographic and workplace factors, consistent with multilevel models of clinician well-being.

Beyond the leadership-outcome nexus, our findings revealed satisfactory resilience and strong professional ethics coexisting with high emotional exhaustion. This paradox, frequently reported in ICU settings, reflects teamwork and culture that support coping and ethics despite chronic strain (26, 27). Coaching emerged as the predominant supervisory style, consistent with supportive managerial practices in clinical contexts (28). The literature advocating transformational and participative leadership in critical care further underscores the value of developmental, relationship-centered approaches (24, 25). The notable proportion of “uncertain” responses regarding leadership perceptions highlights measurement challenges in ICUs and the need for context-sensitive assessment tools (29).

Observed associations with gender, marital status, and workplace align with prior evidence. Gender-linked leadership preferences — women favoring participative/coaching, men more directive — have been documented cross-culturally (24). The association between marital status and resilience suggests that family support may buffer occupational stress (30). The link between medical history and professional ethics implies that lived health experiences enhance empathy and ethical sensitivity, consistent with prior findings (31). Although ancillary, these patterns indicate that demographic and workplace factors shape leadership perceptions and the mobilization of psychological resources in ICU practice.

From an organizational policy perspective, the absence of a direct leadership link with emotional exhaustion does not reduce the need to address burnout, given its impact on quality, safety, and retention (26). Interventions such as optimizing workload and staffing, structured peer support, mental health services, and protected recovery time can complement leadership strategies (10-13, 24, 28, 30). Future research using cohort or case–control designs should clarify causal pathways and test integrated models. Improving leadership measurement, with multi-source ratings and context-calibrated tools, remains essential to capture observed subtleties.

5.1. Conclusions

This study highlights the predominance of coaching leadership among ICU nurses, alongside high resilience and professional ethics, despite moderate emotional exhaustion reflecting critical care demands. The findings underscore that participative, supportive leadership enhances resilience and ethical commitment, improving performance and care quality. Given the negative impact of exhaustion, interventions such as leadership development, organizational support, and mental health promotion are essential. Integrating resilience-building and ethics training into education and professional development will further strengthen coping capacity. Policy efforts should foster collaborative, context-sensitive leadership to sustain a resilient, ethically grounded nursing workforce capable of delivering high-quality critical care.