1. Background

Today, with the rapid advancement of technology, artificial intelligence (AI) has emerged as a cornerstone of transformation in the healthcare system (1). The AI is an interdisciplinary branch of computer science that focuses on designing and developing intelligent systems capable of performing tasks that typically require human cognitive abilities and intelligence (2, 3).

Global market statistics indicate that the value of AI in healthcare, estimated at $15.4 billion in 2022, is projected to grow at an annual rate of 37.5% through 2030. This technological surge underscores that preparing the nursing workforce is not merely desirable but an essential and undeniable necessity (4).

In nursing, AI has not only reduced the workload but also contributed to improving the quality of care, accelerating decision-making, and enhancing communication skills (5, 6). The AI has transformed the specialized roles of nurses, paving the way for greater creativity and strategic thinking within the profession (7). Additionally, AI is fundamentally redefining educational paradigms in nursing. From adaptive learning systems to virtual reality simulations, these technologies hold the potential to revolutionize teaching methods, assessment strategies, and the development of clinical competencies (8).

Various countries, particularly those aiming to strengthen their position in the global innovation landscape, are prioritizing AI as a strategic focus in education and healthcare (9). In line with this, international bodies emphasize the importance of incorporating education on the principles and applications of AI into medical science curricula (10). Accordingly, reforming nursing curricula to integrate AI technologies into both academic and clinical settings is critical for preparing students to practice safely and effectively in the AI era (11). Scientific evidence indicates that insufficient knowledge about AI can culminate in anxiety and concern among students, potentially influencing their professional career choices (12). Additionally, according to studies, the purposeful implementation of AI can enhance students’ clinical self-confidence by 23%, reduce the time required to access medical knowledge by 67%, and improve the accuracy of clinical decision-making by 18%. These findings highlight the transformative potential of AI in cultivating a new generation of competent nurses prepared to navigate the complexities of modern healthcare (8). Nurse educators must adopt evolving pedagogical approaches that incorporate AI to support learners at all educational levels. Likewise, nursing students and practicing nurses must be equipped with the knowledge and skills necessary to critically evaluate AI technologies and integrate them safely into patient-centered, compassionate care (13).

The adoption of AI-related technologies linked to factors such as knowledge, attitudes, and practice (14). Studies indicate a positive and promising attitude toward AI among physicians and nurses. However, most have a low level of knowledge and insufficient skills in working with AI (15). Additionally, due to numerous barriers, the use of AI in healthcare remains limited (16). Nurses’ limited knowledge of AI, particularly in developing countries like Iran, is regarded as a major challenge. A proper understanding of nurses’ levels of knowledge, attitudes, and practice regarding AI can facilitate future educational planning (17).

Despite the transformative potential of AI across all domains of nursing — including management, clinical care, education, policy-making, and research —and the urgent need to prepare nurses for the safe and effective integration of AI technologies, existing studies on nursing students’ knowledge, attitudes, and practices regarding AI reveal considerable gaps (13). These gaps, repeatedly identified in empirical studies and systematic reviews, underscore the necessity for more comprehensive and rigorous research to inform the development of evidence-based educational programs and well-informed policies (18, 19).

2. Objectives

The present study was conducted to determine Iranian nursing students’ perspectives, knowledge, attitudes, and practices regarding AI in 2024 - 2025 in order to address this growing need.

3. Methods

3.1. Study Design

This descriptive-analytical study was conducted during the 2024 - 2025 academic year at the School of Nursing, Abadan University of Medical Sciences, Iran. The appropriate sample size was estimated to be 160 individuals from a population of 275 nursing students using the Cochran formula. Student sampling was carried out through a simple random method. Each student was assigned a number, and the required number of participants was selected using Google Random Number Generator. Participants were then identified based on their assigned numbers. The inclusion criteria required students to be enrolled in the bachelor of nursing program from the second semester onward. The exclusion criterion was incomplete questionnaires, defined as having more than 5% of missing data across all questionnaire items. For data collection, the researcher obtained the necessary permissions from Abadan University of Medical Sciences, and then proceeded to the School of Nursing to sample students. Participants were first provided with the detailed explanations regarding the confidentiality of their information, the research methodology, and how to access the study results. Subsequently, the link to the electronic questionnaire, designed on the DigiSurvey platform, was shared via messaging apps such as Eitaa and WhatsApp with randomly selected students. Participants were instructed to click on the provided link to first complete the informed consent form before proceeding to the questionnaire.

3.2. Data Collection Tools

The data were collected using a questionnaire adapted from Hamedani et al.’s study (17). The first part of the questionnaire included demographic information, and the second part comprised 13 questions assessing nurses’ attitudes toward the use of AI. These questions were measured on a 5-point Likert scale (ranging from “strongly disagree” to “strongly agree”), with each item scored from one to five. A score of 13 - 35 denotes an unfavorable attitude toward AI use, 36 - 50 indicates a relatively favorable attitude, and 51 - 65 shows a favorable attitude. The third part, consisting of 12 questions to examine the practices regarding medical AI from the perspective of nurses, was scored on a 5-point Likert scale as follows: Very high (5 points), high (4 points), low (3 points), very low (2 points), and AI should not be used in this field (1 point). A score of 12 - 32.5 indicates low AI use, 32.6 - 46 denotes moderate AI use, and 47 - 60 shows high AI use. The fourth part consisted of eight questions assessing nurses’ knowledge of AI, using a 3-point Likert scale as follows: Yes, it is correct (3 points), no, it is not correct (2 points), and I do not know (1 point). A score of 8 - 13.5 denotes low knowledge, 13.6 - 19 indicates moderate knowledge, and 20 - 24 shows high knowledge. Additionally, benefits and concerns regarding AI were evaluated through 21 questions. The content validity of the questionnaire was confirmed by expert opinions, and the reliability of its dimensions was established using internal consistency, with a Cronbach’s alpha coefficient of 0.81 (18). In this study, content validity was evaluated by ten faculty members, and its reliability was confirmed with a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.87.

3.3. Data Analysis

Following data collection, the data were analyzed using SPSS software version 27. Descriptive statistics, including measures of central tendency (mean and standard deviation), frequency, and percentage were calculated. For inferential analysis, the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test, independent t-test, analysis of variance (ANOVA), and Pearson’s correlation coefficient were employed, with a significance level set at P < 0.05.

3.4. Ethical Considerations

This study was approved under the ethical approval code of IR.ABADANUMS.REC.1404.023. It was conducted in full compliance with ethical principles throughout both its execution and publication. Participants were provided with comprehensive information regarding the research purpose, expected outcomes, confidentiality measures, and study procedures. Informed consent was obtained from all participants.

4. Results

A total of 160 nursing students participated in the study. The majority reported using AI, although participation in AI workshops and educational courses was limited. Among AI platforms, ChatGPT was the most commonly used tool, while Perplexity was the least used.

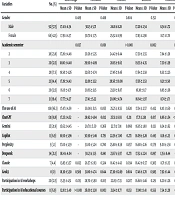

Univariate analysis indicated that gender was not associated with any domain of knowledge, attitudes, practice, benefits, or concerns regarding AI use. However, academic semester showed significant relationships with all domains, with students in higher semesters achieving higher scores, particularly in attitudes and practice. The AI use was associated with lower levels of concern. Furthermore, ChatGPT use was positively associated with higher knowledge, attitudes, and perceived benefits, while users of Gemini and Claude demonstrated relatively higher knowledge and practice levels. In contrast, the use of Copilot, Perplexity, DeepSeek, and Grok3 showed no significant associations. Participation in AI workshops and educational courses was related to higher knowledge and more positive attitudes (Table 1).

| Variables | No. (%) | Knowledge | Attitudes | Practice | Benefits | Concerns | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean ± SD | P-Value | Mean ± SD | P-Value | Mean ± SD | P-Value | Mean ± SD | P-Value | Mean ± SD | P-Value | ||

| Gender | 0.489 | 0.488 | 0.604 | 0.152 | 0.542 | ||||||

| Male | 92 (57.5) | 17.41 ± 4.54 | 30.15 ± 5.71 | 24.81 ± 8.28 | 17.20 ± 2.54 | 8.34 ± 1.72 | |||||

| Female | 68 (42.5) | 17.91 ± 4.37 | 30.70 ± 3.75 | 25.52 ± 8.99 | 17.83 ± 2.98 | 8.17 ± 1.78 | |||||

| Academic semester | 0.037 | 0.001 | > 0.001 | 0.002 | 0.043 | ||||||

| 2 | 38 (23.8) | 17.26 ± 4.48 | 30.26 ± 5.25 | 24.42 ± 6.44 | 17.50 ± 2.55 | 7.84 ± 1.58 | |||||

| 3 | 20 (12.5) | 18.80 ± 4.40 | 29.90 ± 4.89 | 28.85 ± 9.63 | 19.55 ± 4.35 | 7.50 ± 1.39 | |||||

| 4 | 28 (17.5) | 19.50 ± 4.26 | 32.60 ± 4.74 | 27.46 ± 8.46 | 17.64 ± 2.58 | 8.53 ± 2.25 | |||||

| 5 | 23 (14.4) | 17.39 ± 4.43 | 32.08 ± 3.32 | 28.56 ± 10.08 | 17.56 ± 2.53 | 8.21 ± 1.50 | |||||

| 6 | 20 (12.5) | 16.10 ± 4.71 | 30.65 ± 3.15 | 23.30 ± 6.87 | 16.30 ± 1.17 | 8.85 ± 1.56 | |||||

| 7 | 31 (19.4) | 17.77 ± 4.27 | 27.41 ± 5.22 | 20.06 ± 4.74 | 16.64 ± 1.97 | 8.74 ± 1.71 | |||||

| The use of AI | 138 (86.3) | 17.47 ± 4.59 | - | 30.08 ± 5.15 | 0.055 | 25.25 ± 8.55 | 0.620 | 17.54 ± 2.57 | 0.432 | 8.10 ± 1.60 | 0.001 |

| ChatGPT | 131 (81.9) | 17.25 ± 4.52 | - | 29.92 ± 4.84 | 0.012 | 25.51 ± 8.93 | 0.211 | 17.71 ± 2.81 | 0.017 | 8.86 ± 1.54 | < 0.001 |

| Gemini | 35 (21.9) | 15.62 ± 4.45 | - | 29.71 ± 5.50 | 0.366 | 22.71 ± 7.91 | 0.060 | 16.85 ± 1.80 | 0.133 | 8.34 ± 1.62 | 0.796 |

| Copilot | 11 (6.9) | 16.90 ± 3.96 | - | 30.90 ± 5.46 | 0.719 | 22.36 ± 7.00 | 0.271 | 18.09 ± 3.26 | 0.443 | 8.18 ± 1.25 | 0.855 |

| Perplexity | 5 (3.1) | 17.00 ± 3.39 | - | 31.00 ± 3.24 | 0.780 | 25.80 ± 8.58 | 0.857 | 16.80 ± 2.16 | 0.579 | 9.00 ± 1.58 | 0.348 |

| Deepseek | 34 (21.3) | 18.14 ± 4.04 | - | 30.23 ± 3.15 | 0.841 | 23.67 ± 5.97 | 0.271 | 17.52 ± 2.24 | 0.897 | 1.35 ± 8.44 | 0.717 |

| Claude | 7 (4.4) | 13.85 ± 3.57 | 0.023 | 28.57 ± 2.63 | 0.324 | 18.42 ± 4.42 | 0.034 | 16.42 ± 0.57 | 0.305 | 8.71 ± 1.25 | 0.498 |

| Grok3 | 0 (0) | 18.30 ± 3.30 | 0.569 | 31.00 ± 4.74 | 0.644 | 27.30 ± 12.69 | 0.604 | 17.46 ± 2.78 | 0.985 | 7.92 ± 1.44 | 0.451 |

| Participation in AI workshops | 20 (12.5) | 15.35 ± 4.51 | 0.015 | 28.70 ± 3.90 | 0.105 | 22.85 ± 7.13 | 0.207 | 16.60 ± 1.46 | 0.129 | 8.20 ± 1.28 | 0.838 |

| Participation in AI educational courses | 11 (6.9) | 12.81 ± 3.40 | > 0.001 | 26.09 ± 3.30 | 0.003 | 21.54 ± 8.77 | 0.153 | 17.00 ± 1.41 | 0.555 | 7.54 ± 1.29 | 0.152 |

Abbreviations: SD, standard deviation; AI, artificial intelligence.

Overall, the results indicated a moderate level of AI knowledge and attitudes, limited practice, low recognition of AI benefits, and moderate concerns among nursing students (Table 2).

| Variables | Score Range | Lowest Score | Highest Score | Mean ± SD |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Knowledge | 8 - 24 | 9 | 24 | 17.62 ± 4.49 |

| Attitudes | 13 - 65 | 13 | 41 | 38.30 ± 4.96 |

| Practice | 12 - 60 | 12 | 60 | 25.11 ± 8.57 |

| Benefits | 15 - 30 | 15 | 30 | 17.47 ± 2.75 |

| Concerns | 6 - 12 | 6 | 12 | 8.27 ± 1.74 |

Regarding perceptions of AI benefits, students most frequently agreed that AI can increase service speed, reduce medical errors, and provide access to extensive patient data. The least frequently endorsed benefits were job creation and AI-assisted complex decision-making. The most prominent concerns included potential breaches of patient confidentiality, lack of empathy, and the reduction of healthcare team roles (Table 3).

| Variables and Items | Agree | Disagree |

|---|---|---|

| Benefits | ||

| 1) AI reduces healthcare costs. | 145 (90.6) | 15 (9.4) |

| 2) AI reduces the duration of patient hospital stay. | 138 (86.3) | 22 (13.8) |

| 3) AI increases the speed of service delivery to clients. | 149 (93.1) | 10 (6.3) |

| 4) AI can eliminate many current medical weaknesses. | 142 (88.8) | 8 (11.3) |

| 5) AI can reduce the heavy workload of medical team members. | 141 (88.1) | 19 (11.9) |

| 6) AI creates new jobs in the healthcare field. | 103 (66.4) | 57 (35.6) |

| 7) AI has no physical limitations or fatigue. | 141 (88.1) | 19 (11.9) |

| 8) AI is not constrained by time or location. | 130 (81.3) | 30 (18.8) |

| 9) AI can help reduce medical errors. | 148 (92.5) | 12 (7.5) |

| 10) AI can reduce differences in judgments and diagnoses among physicians. | 138 (86.3) | 22 (13.8) |

| 11) AI opinions can be relied upon in making difficult decisions. | 95 (59.4) | 65 (40.6) |

| 12) By using AI, doctors will have more time for their patients and for focusing on tasks that are more complex. | 122 (76.3) | 38 (23.8) |

| 13) AI systems provide reliable reports by analyzing patient data. | 120 (75) | 40 (25) |

| 14) AI provides researchers with access to a massive database of anonymized patients from across the country. | 148 (92.5) | 12 (7.5) |

| 15) The use of AI increases profitability for medical centers. | 142 (88.8) | 18 (11.3) |

| Concerns | ||

| 16) There is a potential for the disclosure of patient confidential information by certain individuals or hackers. | 129 (80.6) | 31 (19.4) |

| 17) AI increases the workload of treatment team members. | 45 (28.1) | 115 (71.9) |

| 18) AI lacks the ability to empathize patients and consider their emotional behavior. | 115 (71.9) | 45 (28.1) |

| 19) AI can potentially harm the physician-patient relationship. | 106 (66.3) | 54 (33.8) |

| 20) AI reduces the number of medical team members needed in the community. | 94 (58.8) | 96 (41.3) |

| 21) AI diminishes the role of medical team members in treating patients in the future. | 107 (66.9) | 53 (33.1) |

Abbreviation: AI, artificial intelligence.

a Values are expressed as No. (%).

Correlation analysis revealed positive relationships among knowledge, attitudes, and practice, as well as between practice and perceived benefits, whereas concerns were inversely associated with these domains (Table 4).

| Variables | Age | Knowledge | Attitudes | Practice | Benefits | Concerns |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 1 | r = -0.157, P = 0.084 | r = -0.084, p = 0.290 | r = -0.087, P = 0.272 | r = -0.155, P = 0.146 | r = 0.155, P = 0.053 |

| Knowledge | r = -0.157, P = 0.903 | 1 | r = 0.269, P = 0.001 | r = 0.099, P = 0.212 | r = 0.105, P = 0.186 | r = 0.149, P = 0.059 |

| Attitudes | r = -0.084, P = 0.290 | r = 0.269, P = 0.001 | 1 | r = 0.384, P < 0.001 | r = 0.086, P = 0.281 | r = 0.275, P < 0.001 |

| Practice | r = -0.087, P = 0.290 | r = 0.099, P = 0.212 | r = 0.384, P < 0.001 | 1 | r = 0.440, P < 0.001 | r = -0.235, P = 0.003 |

| Benefits | r = -0.115, P = 0.146 | r = 0.105, P = 0.186 | r = 0.086, P = 0.281 | r = 0.440, P < 0.001 | 1 | r = -0.230, P = 0.003 |

| Concerns | r = 0.155, P = 0.051 | r = 0.149, P = 0.059 | r = 0.275, P < 0.001 | r = -0.235, P < 0.001 | r = -0.230, P = 0.003 | 1 |

5. Discussion

The present study aimed to evaluate nursing students’ knowledge, attitudes, and practice regarding AI, as well as their perceived benefits and concerns about its application in nursing care. Our findings revealed that nursing students possess a moderate level of AI knowledge. This observation aligns with previous studies conducted in Iran, Jordan, India, and Lebanon, which also reported moderate AI knowledge among nursing and healthcare students (17-22). These results suggest that the pace of AI integration in healthcare has outstripped the adaptation of educational curricula, leaving students inadequately prepared to fully leverage these technologies. Even in contexts where physicians and healthcare workers demonstrate satisfactory AI knowledge, such as in Saudi Arabia and Pakistan, structured AI education remains limited (23, 24), highlighting the need for formal AI curricula in nursing programs. Conversely, in China, studies reported lower levels of AI knowledge among healthcare professionals, indicating significant regional and institutional variations in AI education (25). Differences in knowledge between students and professionals may also be influenced by clinical responsibilities and exposure to patient care, which provide healthcare workers with more opportunities to engage with AI in practice (24, 26).

Students’ attitudes toward AI were generally positive and moderate in intensity. Similar findings have been reported in Syria, Iran, Jordan, and Lebanon, where favorable attitudes correlated with a greater willingness to adopt AI technologies (18-22, 27). This positivity likely reflects students’ recognition of AI’s potential to enhance efficiency, reduce medical errors, and facilitate access to large patient datasets (20, 22, 27). Nevertheless, ethical and privacy concerns remain salient, as documented in multiple contexts, and demographic factors such as age, gender, and technological background can further influence attitudes (25, 28). The absence of significant demographic effects in our study may be attributed to the homogeneity of the sample, which was drawn from a single university.

Despite these positive attitudes, the practical use of AI tools among students was limited, with ChatGPT being the most frequently used platform. This gap between favorable perceptions and actual practice has been reported in Iran, Saudi Arabia, and Pakistan (26, 29, 30), and may be due to certain barriers, such as insufficient training, inadequate infrastructure, absence of standardized guidelines, and ethical or legal concerns (29, 31, 32). Studies conducted in Saudi Arabia, Turkey, and South Korea emphasize the importance of AI-friendly educational environments and structured workshops to enhance students’ practical AI skills (30, 33, 34). Moreover, as shown in Table 1, the academic semester was significantly associated with all domains of knowledge, attitudes, practice, and perceived benefits, suggesting that educational maturity and cumulative exposure to clinical experiences enhance students’ readiness to engage with AI. Higher-semester students demonstrated better knowledge, more positive attitudes, and greater AI practice, consistent with earlier studies indicating that academic progression correlates with digital competence and self-efficacy in technology use (19, 22). Participation in AI-related courses and workshops demonstrated a significant positive impact on knowledge and attitudes, highlighting the role of structured education in fostering AI acceptance. Furthermore, ChatGPT users exhibited significantly higher scores in knowledge, attitudes, and perceived benefits, implying that frequent interaction with accessible AI platforms can reinforce both the cognitive and affective aspects of technology adoption. In contrast, users of less common tools such as Copilot, DeepSeek, or Perplexity did not show significant associations, perhaps due to lower familiarity and limited healthcare-oriented functionality.

From the students’ perspective, the most salient benefits of AI include faster service delivery, a reduction in medical errors, and access to extensive patient databases. These perceptions have been consistently reported in Syria, Jordan, Saudi Arabia, and Iran (20, 23, 24, 26, 27, 34). Positive attitudes and recognition of these benefits appear to facilitate AI adoption, while concerns can act as barriers. Major concerns identified include potential breaches of patient confidentiality, AI’s inability to empathize with patients, and the possible diminishment of healthcare team roles (35-37). Broader issues, such as legal liability and the lack of standard guidelines, have also been highlighted in Iran, emphasizing the importance of addressing these challenges to ensure the safe integration of AI (29).

These findings can be interpreted within the theoretical framework of technology acceptance models (TAMs), which posit that perceived usefulness enhances adoption motivation, whereas perceived risk or ethical conflict serves as a barrier (1-3). Educational institutions and clinical policymakers should address these opposing forces simultaneously, ensuring that nursing students acquire both the technical competencies and ethical awareness necessary for responsible AI use. As shown in Table 4, positive correlations were found among knowledge, attitudes, and practice, and between practice and perceived benefits, while concerns were inversely related to these domains. These relationships align with the TAM and previous findings from Iran, Jordan, and Saudi Arabia (17, 20), confirming that greater knowledge and favorable attitudes facilitate higher AI engagement and awareness of its benefits. Conversely, higher concerns — particularly regarding privacy and empathy — can inhibit practical use. Therefore, improving AI literacy may indirectly reduce concerns by increasing understanding of AI’s capabilities and ethical safeguards.

Despite providing significant findings, the generalizability of the results to other universities and student populations in different regions or countries is limited, as the sampling was conducted at only one university of medical sciences. Hence, it is recommended that future studies employ longitudinal designs with more extensive sampling, using mixed quantitative and qualitative methods to more deeply and comprehensively investigate the various dimensions of AI adoption and practice among medical students and other relevant groups.

5.1. Conclusions

This study provides a multifaceted picture of the level of knowledge, attitudes, and practice regarding AI among nursing students at Abadan University of Medical Sciences in Iran. Despite the widespread use of AI technologies, particularly ChatGPT, students’ knowledge and attitudes toward these technologies remain moderate, and their practical application is limited. This gap between use and knowledge highlights the need for targeted educational interventions in AI. Participation in relevant workshops and courses significantly increased students’ knowledge and fostered more positive attitudes. Therefore, specialized and continuous training is essential to strengthen students’ readiness for and acceptance of AI. However, concerns regarding ethical and legal issues suggest that the broad adoption of AI depends on addressing these barriers. The significant positive relationships among knowledge, attitudes, and practice of AI suggest that improving knowledge and attitudes can reduce concerns and promote effective use, particularly among higher-semester students who demonstrated superior performance in these areas. Ultimately, this study emphasizes that to fully realize AI potential in nursing, comprehensive educational programs, robust data protection measures, and coherent ethical frameworks must be developed and implemented to address existing concerns and facilitate technology acceptance.