1. Context

Climate change has emerged as one of the most pressing global health challenges of the 21st century, with far-reaching implications for human health, healthcare systems, and the environment. Rising global temperatures, extreme weather events, air pollution, water scarcity, and shifting disease patterns are increasingly recognized as significant threats to public health (1). The healthcare sector, while tasked with treating the health consequences of climate change, is also a considerable contributor to environmental degradation through high energy consumption, waste generation, and carbon emissions. Thus, the interplay between climate change and healthcare presents a dual challenge: Safeguarding health while minimizing the ecological footprint of health services (2).

Within this context, sustainability in healthcare has become a critical area of focus. Sustainable healthcare practices aim to reduce environmental impacts, optimize the use of resources, and ensure the long-term resilience of healthcare systems (3). Initiatives such as green hospital design, energy efficiency, waste reduction, and sustainable procurement are increasingly discussed at policy and institutional levels (4). However, the successful implementation of these initiatives depends not only on systemic changes but also on the perspectives, attitudes, and actions of healthcare professionals, who serve as both frontline responders to climate-related health issues and key agents in driving sustainable practices (5).

Nurses, who represent the largest segment of the healthcare workforce, occupy a particularly influential role in this regard. Due to their close patient contact, community engagement, and involvement in a wide range of clinical and public health activities, nurses are uniquely positioned to identify and address the health consequences of climate change (6). Moreover, their professional values — emphasizing care, advocacy, and holistic health — align with the principles of sustainability (7). Yet, nurses also face barriers such as limited knowledge, lack of institutional support, resource constraints, and competing clinical demands that may hinder their active participation in climate change mitigation and sustainable healthcare initiatives (8, 9).

In recent years, a growing body of qualitative research has explored nurses’ perspectives on climate change and sustainability, offering valuable insights into their awareness, attitudes, perceived responsibilities, and experiences (10, 11). These studies highlight both opportunities and challenges for integrating climate considerations into nursing practice (12). However, the findings are scattered across diverse contexts, healthcare systems, and cultural settings (3, 13). Without synthesis, it is difficult to generate a comprehensive understanding of the shared meanings, values, and barriers that shape nurses’ engagement with climate and sustainability issues (14).

Despite the growing body of qualitative research exploring nurses’ experiences and perspectives on climate change and sustainability (11, 15), a critical gap persists in the literature: No comprehensive meta-synthesis has been conducted to integrate these findings and draw broader, actionable conclusions. This gap hinders a holistic understanding of nurses’ roles, perceptions, and challenges in addressing climate change within healthcare, limiting the development of evidence-based strategies to support their pivotal contributions to sustainable practices. A meta-synthesis provides the opportunity to move beyond individual study results, uncover deeper patterns, and develop interpretive insights that can inform nursing practice and health policy at both national and international levels (16).

2. Objectives

Therefore, the present study aims to conduct a qualitative meta-synthesis of existing research on nurses’ perspectives regarding climate change and sustainability in healthcare. By systematically analyzing and integrating qualitative evidence, this study seeks to identify common themes, explore underlying meanings, and generate a nuanced understanding of how nurses perceive their roles, responsibilities, and challenges in relation to climate change and sustainable healthcare practices. The insights derived will contribute to the global discourse on climate change and health while offering practical implications for building a more environmentally responsible and resilient healthcare system.

3. Methods

3.1. Reporting Guidelines

The reporting of this review adheres to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines (17) and the Enhancing Transparency in Reporting the Synthesis of Qualitative Research (ENTREQ) guidelines (18). The study protocol was registered in PROSPERO (ID: CRD420251130772). The PRISMA and the Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP) checklist checklists are provided as an Appendix 1 in Supplementary File.

3.2. Information Sources and Search Strategy

A comprehensive literature search was undertaken across multiple electronic databases, including PubMed, Scopus, Web of Science, CINAHL, and PsycINFO. The search targeted peer-reviewed articles published in English between January 1, 2015, and April 30, 2025, in order to capture studies reflecting contemporary nursing practice within the context of increasing climate change awareness and sustainability discourse. The search strategy for each database, including keywords and medical subject headings (MeSH) terms, is detailed in Table 1.

| Database | Search String |

|---|---|

| PubMed | (“Nurses”[MeSH] OR “Nursing”[MeSH] OR “nurse*”) AND (“Climate Change”[MeSH] OR “Environmental Sustainability” OR “sustainable healthcare”) AND (“perceptions” OR “attitudes” OR “perspectives” OR “qualitative”) |

| Scopus | (TITLE-ABS-KEY(nurse* OR nursing) AND (“climate change” OR “environmental sustainability” OR “sustainable healthcare”) AND (perception* OR attitude* OR perspective* OR qualitative)) |

| Web of Science | TS=((nurse* OR nursing) AND (“climate change” OR “environmental sustainability” OR “sustainable healthcare”) AND (perception* OR attitude* OR perspective* OR qualitative)) |

| CINAHL | (MH “Nurses” OR MH “Nursing” OR nurse*) AND (MH “Climate Change” OR “environmental sustainability” OR “sustainable healthcare”) AND (perception* OR attitude* OR perspective* OR qualitative) |

| PsycINFO | (Nurse* OR nursing) AND (“climate change” OR “environmental sustainability” OR “sustainable healthcare”) AND (perception* OR attitude* OR perspective* OR qualitative) |

Abbreviation: MeSH, medical subject headings.

a Search terms included synonyms such as “ecological responsibility”, “green healthcare”, and “environmental stewardship” to ensure comprehensiveness. Boolean operators (AND, OR) were used to combine terms. Manual screening of reference lists supplemented the database searches.

3.3. Eligibility Criteria

Eligibility was determined using the SPIDER framework (19):

1. Sample: Registered nurses, nursing students, and nurse educators involved in direct patient care, professional development, or education. Studies involving other healthcare professionals were included only when nurses’ perspectives were clearly distinguishable. Studies focusing exclusively on non-nursing health professionals were excluded.

2. Phenomenon of interest: Experiences, perceptions, and attitudes of nurses regarding climate change, sustainability, or environmentally responsible practices within healthcare. Studies not directly addressing these phenomena were excluded.

3. Design: Qualitative studies (e.g., interviews, focus groups, ethnography) and mixed-methods studies with substantial qualitative components. Purely quantitative studies, reviews without primary data, and grey literature were excluded.

4. Evaluation: Perceived roles, responsibilities, barriers, and facilitators regarding climate change and sustainable practices in nursing and healthcare contexts.

5. Research type: Only peer-reviewed, original qualitative research articles published in English between 2015 and 2025 were considered.

3.4. Study Selection

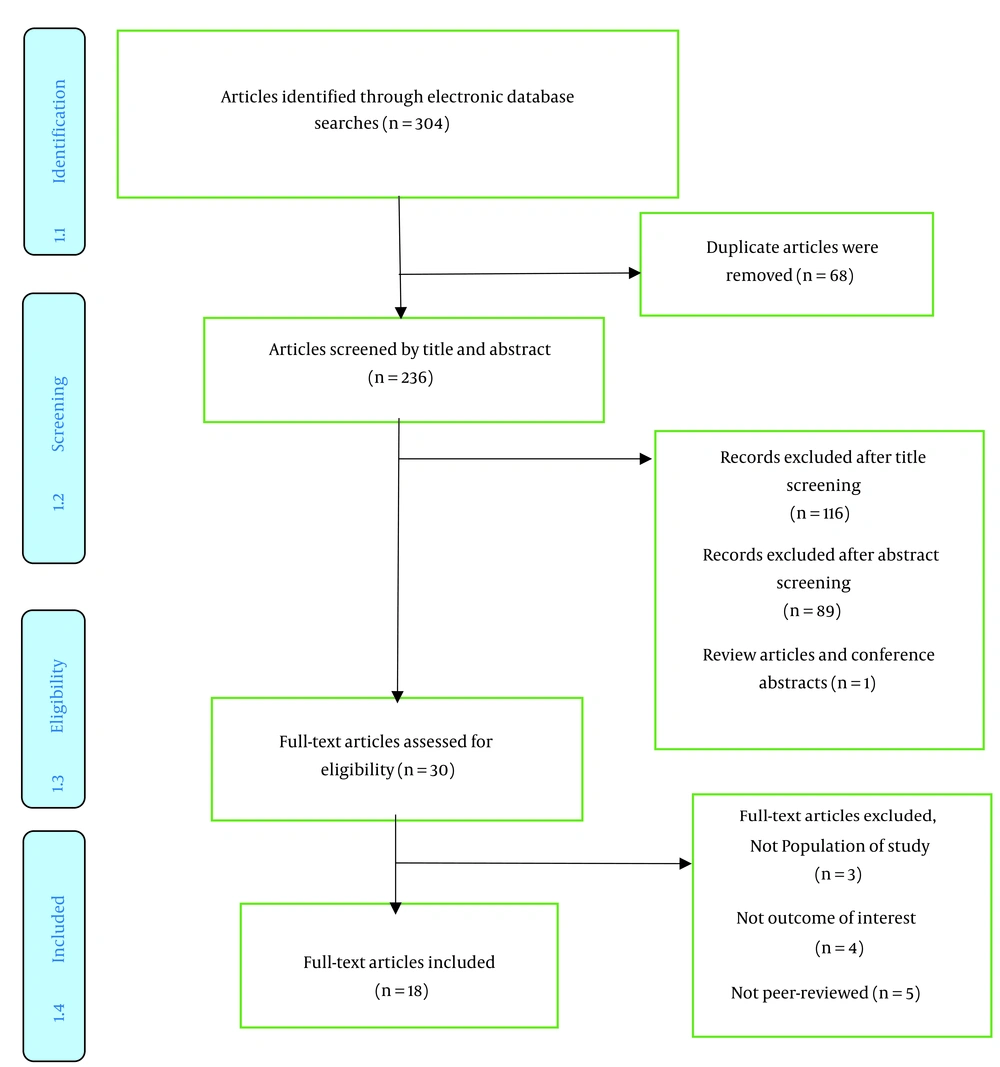

Two independent reviewers (MT) and (SM) screened all titles and abstracts for relevance. Full-text articles were then reviewed against the inclusion criteria. Discrepancies in selection were resolved through discussion, with a third reviewer (RT) consulted when necessary. The PRISMA flow diagram provides details of the screening process (Figure 1).

3.5. Data Extraction

A structured data extraction form was developed and pilot-tested on three studies to ensure clarity. Data extracted included: Authors, year of publication, country, aims, participant characteristics (role, number, setting), methodological approach (data collection and data analysis), qualitative findings (themes, subthemes), and representative participant quotes. Extraction was conducted independently by two reviewers, with disagreements resolved through consensus. For mixed-methods studies, only qualitative findings (narratives, direct quotes, thematic results) were extracted, excluding numerical data.

3.6. Approach to Data Synthesis

Thematic synthesis was conducted to identify and integrate key themes from the qualitative studies, following the framework outlined by Thomas and Harden (2008) (20). This approach combined inductive and deductive coding to ensure a comprehensive exploration of nurses’ perspectives on climate change and sustainability. Two researchers independently coded the data using NVivo 12 software (QSR International, 2018), with manual coding applied to preserve interpretive rigor, generating initial "free codes" from participant quotes and author interpretations. Codes were then collaboratively refined through iterative discussions to develop a cohesive thematic framework, ensuring inter-rater reliability. While the synthesis primarily focused on qualitative insights, simple counts of studies contributing to each theme and sub-theme were used to illustrate their prevalence across the dataset. This approach enhanced the clarity of the findings, enabling readers to understand the relative frequency and significance of themes such as nurses’ perceptions, health impacts, barriers, and recommended strategies for sustainable healthcare practices.

3.7. Quality Appraisal

The methodological quality of included studies was appraised using the CASP checklist for qualitative studies (21). Two reviewers independently assessed each study across ten criteria, including research aims, methodology, data collection, analysis, reflexivity, and ethical considerations. Each criterion was scored as "Yes", "No", or "Can’t Tell" to evaluate the extent to which studies met qualitative research standards. Most studies demonstrated clear aims, appropriate methodologies, and rigorous data collection, though some showed limitations in reflexivity and detailed ethical reporting. Discrepancies were resolved by discussion or with the input of a third reviewer. No studies were excluded based on quality appraisal; instead, the assessment was used to contextualize findings and enhance transparency in synthesis. A summary of quality appraisal results is provided in the Appendix 1 in Supplementary File.

4. Results

4.1. Study Selection Process

The study selection process began with a comprehensive search across electronic databases (PubMed, Scopus, Web of Science, CINAHL, and PsycINFO), identifying 304 records related to nurses’ perspectives on climate change and sustainability in healthcare. After removing 68 duplicates, 236 articles underwent title and abstract screening, resulting in the exclusion of 116 records based on title and 89 based on abstract, along with one review article and conference abstract. Thirty full-text articles were then assessed for eligibility, with nine excluded. Ultimately, 18 full-text articles met the inclusion criteria, as outlined in the SPIDER framework, and were included in the qualitative meta-synthesis, as detailed in the PRISMA flow diagram (Figure 1).

4.2. Characteristics of Included Studies

The systematic review qualitative meta-synthesis included 18 peer-reviewed studies, exploring nurses’ perspectives on climate change and sustainability in healthcare across diverse global contexts, including Turkey (15, 22-24), Saudi Arabia (25), Italy (26, 27), Spain (28), Nepal (29), Egypt (14), Canada (10, 11), Kazakhstan (30), Poland (31), Philippines (32), Sweden (33, 34), and Finland (35). The studies employed various qualitative designs, such as descriptive phenomenological (24, 25, 31), exploratory (14, 15, 23, 25-30, 32-34), naturalistic inquiry (10), and focused ethnography (11), with data primarily collected through semi-structured interviews (10, 11, 14, 23-28, 31-35), focus group discussions (15, 29, 30, 35), and mixed-methods approaches incorporating surveys or online questionnaires (15, 22, 32). Participant groups predominantly comprised registered nurses (10, 11, 14, 23, 25-28, 31, 32, 34, 35), nursing students (22, 24, 29, 30, 33), and nurse educators (29), with sample sizes ranging from 6 to 154 participants. More details regarding the included studies are provided in Table 2.

| Author, Year, and Reference | Country | Design | Data Collection Method | Data Analysis Approach | Key Themes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kasikci et al., 2025 (24) | Turkey | Descriptive phenomenological | Semi-structured interviews (n = 12), and demographic information form | Content analysis (inductive) | Perceived impacts of carbon footprint, and carbon footprint reduction strategies |

| Badawy et al., 2025 (25) | Saudi Arabia | Qualitative exploratory (phenomenological) | Semi-structured interviews (n = 23) | Thematic content analysis | Operationalizing sustainability, educational and advocacy roles, and barriers to sustainability |

| Bartoli et al., 2025 (27) | Italy | Qualitative content analysis | In-depth interviews (n = 27) | Thematic analysis | Concepts of environmental sustainability in ICUs, critical issues related to sustainable intervention in ICUs, and proactive environmental sustainability attitudes in ICUs |

| Caraballo-Betancort et al., 2025 (28) | Spain | Qualitative, descriptive study | Semi-structured online interviews (n = 31) | Inductive thematic analysis | General knowledge of climate change, knowledge of climate change and health, knowledge of actions to address climate change, and knowledge development |

| Ghimire A. and Ghimire P., 2025 (29) | Nepal | Qualitative, exploratory and descriptive | Four focus group discussions (n = 12) | Thematic analysis | Bridging classroom and community, urban-rural equity, and interprofessional resilience |

| Sengul et al., 2025 (15) | Turkey | Sequential mixed-methods | Quantitative survey (n = 95), and focus group discussions (n = 23) | Thematic analysis | Structural factors, process, outcome, and future perspective |

| Zoromba and EL-Gazar, 2025 (14) | Egypt | Descriptive qualitative | Semi-structured interviews (n = 15) | Thematic analysis | Attitudes, practices, and barriers and facilitators |

| Rempel et al., 2025 (10) | Canada | Naturalistic inquiry, qualitative description | Semi-structured interviews (n = 12) | Thematic analysis | Health impacts, climate action, and system influences |

| Ediz and Uzun, 2025 (23) | Turkey | Qualitative, descriptive- | Semi-structured interviews (n = 35) | Thematic analysis | Perception of the global climate crisis, effects of the global climate crisis, effects of the global climate crisis on mental health, reflections of the global climate crisis on nursing, and nurses’ views on prevention and intervention studies |

| Bolgeo et al., 2024 (26) | Italy | Qualitative exploratory | Semi-structured interviews (n = 42) | Framework analysis | Concept of disease in relation to environmental exposure, dangers of chemical and physical substances, and environmental changes cause concern and a sense of helplessness |

| Balay-Odao et al., 2024 (30) | Kazakhstan | Qualitative, descriptive-exploratory | Focus group discussions (n = 29) | Thematic analysis | Impact of environment on health, sustainability practices, interdisciplinary collaboration, intrinsic motivation, and challenges and barriers |

| Kosydar-Bochenek et al., 2023 (31) | Poland | Qualitative phenomenological | Semi-structured interviews (n = 22) | Theme analysis, van Manen’s method | Participation in making decisions, companionship, job satisfaction, and changes |

| Tanay et al., 2023 (32) | Philippines | Qualitative exploratory survey | Online survey (n = 46) | Thematic analysis | Effects of climate change causing disruption and delay in provision of patient care, impact of climate change on nurses and a deep sense of duty, and perceived impact on patients with cancer |

| Anaker et al., 2021 (33) | Sweden | Qualitative, descriptive exploratory | Individual in-depth interviews (n = 8), personal meetings (n = 2), and one group interview (n = 2) | Qualitative content analysis | A gloomy future, shared responsibility, right to a good life, nurses’ role, and difficulty applying |

| Ergin et al., 2021 (22) | Turkey | Mixed method study | Global Warming Questionnaire (n = 154), and focus group discussions (n = 19) | Focus group discussions, with themes derived | Global warming perception, impact on health, methods of protection, roles of nurses, and nursing education |

| Iira et al., 2021 (35) | Finland | Qualitative, and descriptive | Semi-structured focus group interviews | Qualitative descriptive analysis of transcribed interviews (n = 6) | Observed health changes, inadequate education, and need for curriculum inclusion |

| Kalogirou et al., 2020 (11) | Canada | Focused ethnography | Semi-structured interviews (n = 22), and participant observations | Thematic analysis | Muddled terminology; Climate change and health; and Nursing’s relationship to climate change |

| Anaker et al., 2015 (34) | Sweden | Qualitative, descriptive exploratory | Individual in-depth interviews (n = 8), and two focus groups (n = 10) | Qualitative content analysis | Incongruence with daily work, and public health as a co-benefit |

4.3. Synthesis of Findings

Thematic synthesis yielded four overarching themes and 13 subthemes. These encompassed: Nurses’ perceptual constructs of climate change and sustainability; ramifications for health outcomes and healthcare provision; impediments to sustainable practices; and strategic interventions/recommendations for implementation (Table 3). These are delineated below, substantiated by representative excerpts from the primary studies.

| Themes and Sub-themes | Study References |

|---|---|

| Nurses’ perceptions of climate change and sustainability | |

| Conceptual understanding of sustainability | (14, 25-28, 30, 33, 34) |

| Responsibility and ethical duty | (23, 25, 30, 33-35) |

| Personal vs. professional divide | (11, 14, 22, 24, 32) |

| Impacts on health and healthcare delivery | |

| Effects on patient health (e.g., respiratory, mental) | (10, 23, 26, 28, 30, 32, 33, 35) |

| Disruptions in care provision | (10, 11, 15, 24, 31, 32, 35) |

| Vulnerability of specific populations (e.g., cancer patients, elderly) | (15, 26, 28, 32) |

| Barriers to sustainable practices | |

| Organizational and infrastructural challenges | (14, 15, 27, 31, 34) |

| Lack of education and awareness | (11, 23-25, 30) |

| Economic and workload constraints | (24, 28, 32, 34) |

| Strategies/recommendations for action | |

| Individual-level practices (e.g., waste reduction) | (14, 22, 24, 25, 30) |

| Institutional and policy interventions | (14, 15, 30, 33, 34) |

| Education and interdisciplinary collaboration | (10, 11, 22, 23, 30) |

| Leadership and advocacy roles | (14, 15, 24, 25, 32) |

4.4. Nurses’ Perceptions of Climate Change and Sustainability

This theme elucidates nurses’ cognitive frameworks regarding climate change as an anthropogenic perturbation and sustainability as an ethical imperative, frequently delineated across personal and occupational domains. The sub-theme of conceptual understanding of sustainability underscored definitions predicated on resource stewardship and intergenerational equity, exemplified by "Sustainability is a shared responsibility... to protect the environment for future generations" (33). Responsibility and ethical duty manifested as nurses’ normative obligation to champion ecologically viable protocols, as articulated in "Nurses are important actors but need more education... there is hope" (34). The personal vs. professional divide delineated a dichotomy wherein nurses enacted sustainable behaviors individually yet encountered institutional friction, as evidenced by "I think it’s definitely like [this study] decided to raise some discussion... but there’s this awareness, like, you know what you can do as an individual person" (11).

4.5. Impacts on Health and Healthcare Delivery

Nurses attributed climate change to tangible health sequelae and operational disruptions in service delivery, with accentuated susceptibility among delineated cohorts. Within effects on patient health, phenomena such as pulmonary pathologies and psychological morbidities predominated, illustrated by "I feel like these days there are more... mental health issues... whether that affects people’s moods here in the north" (Iira) and "Climate change has a high impact on human health... It depends on adaptation" (30). Disruptions in care provision encompassed meteorological-induced latencies, as in "The sudden change in weather can delay your way of giving immediate care to your patients" (14). Vulnerability of specific populations targeted cohorts like geriatric and oncological patients, wherein "immunocompromised" individuals exhibited heightened peril from contaminants and thermal extremes, noting "The patient will be deprived with the basic human necessities such as clean air... important to a cancer patient" (32).

4.6. Barriers to Sustainable Practices

Impediments to ecologically attuned practices encompassed systemic deficiencies, epistemic lacunae, and operational exigencies. Organizational and infrastructural challenges were characterized as "The issues involved were too complex, overwhelmingly large and difficult to grasp" (34). Lack of education and awareness engendered preparatory deficits, with "The common problem that we have now is the lack of campaign and awareness... we do not have courses in environmental sustainability" (30). Economic and workload constraints precipitated prioritization dilemmas, such as "Saving lives is important in healthcare... Time as an obstacle to thinking about the environment" (10).

4.7. Strategies/Recommendations for Action

Nurses advocated hierarchical interventions to embed sustainability paradigms. Individual-level practices prioritized micro-level actions, such as "We put our waste in a proper bin... Recycling is important to prevent air, water and land pollution" (30). Institutional and policy interventions necessitated structural reforms, including "Environmental sustainability should be incorporated into the curriculum... but this should be done regularly" (23). Education and interdisciplinary collaboration emphasized synergetic frameworks, with "Interdisciplinary collaboration is critical... bringing experts from different specialties together" (30). Leadership and advocacy roles framed nurses as pivotal agents, as in "We need to inform the community about climate change awareness. Brochures and training programs can be organized" (15).

4.8. Line of Argument Synthesis and Conceptual Model

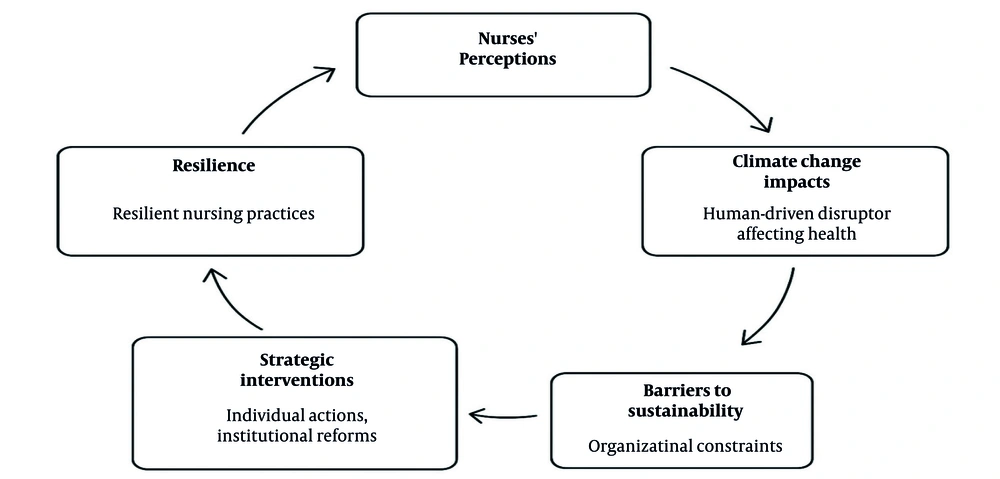

Nurses conceptualize climate change as a pivotal anthropogenic disruptor necessitating ethical sustainability imperatives, notwithstanding impediments such as infrastructural inadequacies and occupational burdens that attenuate implementation. Ramifications disproportionately manifest in vulnerable populations and service perturbations, whereas strategic imperatives underscore nurses’ advocacy potential through pedagogical and policy mechanisms. Remediation of interlinked barriers — encompassing perceptual, institutional, and operational spheres — via collaborative paradigms is imperative for advancing ecologically resilient nursing praxis.

The conceptual model from the line of argument synthesis highlights the interplay between nurses’ perceptions, climate change impacts, barriers to sustainability, and strategic interventions in healthcare. Nurses view climate change as a human-driven disruptor affecting health and healthcare delivery, especially for vulnerable groups, driving an ethical need for sustainability. Shaped by personal and professional values, these perceptions face systemic barriers like organizational constraints, limited education, and workload pressures, hindering sustainable practices. Strategic interventions — individual actions (e.g., waste reduction), institutional reforms (e.g., policy integration), interdisciplinary collaboration, and advocacy — enable nurses to overcome these barriers, fostering resilient nursing practices that mitigate climate impacts and promote health equity. This cyclical model emphasizes integrated efforts across perceptual, operational, and systemic domains to advance healthcare sustainability (Figure 2).

5. Discussion

This qualitative meta-synthesis illuminates nurses’ critical role in addressing climate change and sustainability in healthcare through four key themes: Nurses’ perceptions of climate change and sustainability, impacts on health and healthcare delivery, barriers to sustainable practices, and strategies for action. By synthesizing qualitative evidence, this study provides a comprehensive understanding of nurses’ experiences, challenges, and potential contributions to sustainable healthcare.

The meta-synthesis revealed that nurses perceive sustainability as an ethical imperative, emphasizing resource stewardship and intergenerational equity, yet often face a personal-professional divide where individual eco-friendly behaviors are not readily translated into professional practice. This aligns with another study, which noted that nurses recognize environmental health as part of their ethical duty but struggle to integrate it into clinical roles due to institutional barriers (36). Similarly, another study found that nurses view climate change as a public health issue, reinforcing the ethical alignment with sustainability principles, consistent with the International Council of Nurses (ICN) code of ethics (2021) (37), which underscores nurses’ responsibility to promote health in the context of environmental challenges. However, in contrast, another study reported higher environmental awareness among nurses in Nordic countries, where sustainability is more embedded in healthcare culture, suggesting that contextual factors influence the extent of the personal-professional divide (38). Addressing this divide requires aligning personal motivations with professional opportunities through supportive policies and training.

The identified health impacts, including respiratory and mental health issues, are consistent with epidemiological evidence linking climate change to increased disease burden, such as asthma exacerbations and psychological distress (39). Disruptions in care provision due to extreme weather events align with reports of climate-related healthcare system challenges, particularly in resource-constrained settings (40). The heightened vulnerability of specific populations, such as cancer patients and the elderly, underscores the disproportionate impact of environmental stressors on immunocompromised groups, echoing findings from studies on climate vulnerability (41). These impacts necessitate adaptive healthcare strategies, including contingency planning for service continuity during environmental crises. The synthesis identified climate change’s effects on patient health, including respiratory and mental health issues, and disruptions in care delivery due to extreme weather events, with vulnerable populations like the elderly and immunocompromised patients disproportionately affected. These findings are consistent with another study, which documented increased respiratory illnesses and mental health challenges linked to climate change, emphasizing the burden on healthcare systems (42). Likewise, another study highlighted disruptions in healthcare delivery due to extreme weather, particularly in low-resource settings, aligning with our findings on service interruptions (43). In contrast, a research reported less significant mental health impacts in regions with robust adaptive measures, indicating that healthcare system resilience may mitigate some climate-related effects (44). These barriers suggest that sustainable practices require not only individual commitment but also systemic support to overcome entrenched operational challenges.

Systemic barriers, including organizational constraints, lack of education, and workload pressures, were identified as significant impediments to sustainable nursing practices. These findings resonate with another research that identified inadequate infrastructure, such as limited recycling systems, as a major barrier to sustainability in healthcare settings (45). Similarly, a lack of environmental sustainability training in nursing curricula was found (36), corroborating the epistemic gaps found in this synthesis. However, in contrast, another study reported that some European nursing programs have begun integrating sustainability education (46), suggesting progress in certain contexts that contrasts with the broader educational deficits identified in our study.

The synthesis proposed multi-level strategies, including individual actions (e.g., waste reduction), institutional reforms (e.g., curriculum integration), interdisciplinary collaboration, and advocacy roles to advance sustainability. These align with another research, which emphasized the efficacy of nurse-led waste reduction initiatives in hospital settings (47), while a study advocated for sustainability-focused nursing curricula to enhance environmental awareness (48). Interdisciplinary collaboration is supported by evidence of successful cross-sectoral partnerships in addressing climate-related health challenges (49). In contrast, another study found limited engagement in advocacy roles among nurses due to competing clinical priorities, indicating variability in the feasibility of leadership roles across different healthcare systems (50).

The synthesis underscores nurses’ potential to lead sustainable healthcare practices while highlighting the need to overcome systemic barriers through targeted interventions. Consistent findings from external studies reinforce the ethical and practical necessity for nurses to engage in environmental stewardship, yet inconsistencies highlight context-specific challenges, such as varying levels of awareness and institutional support. To address the personal-professional divide, healthcare systems should implement policies that align nurses’ values with professional opportunities, such as mandatory sustainability training and resource allocation for eco-friendly practices. The identified health impacts call for adaptive strategies, including contingency planning to ensure care continuity during climate-related disruptions, particularly for vulnerable populations. Future research should prioritize quantitative evaluations of sustainability interventions, such as their impact on clinical outcomes, and comparative studies across diverse healthcare systems to identify scalable strategies. These efforts will enhance nurses’ capacity to mitigate climate change impacts and promote health equity, aligning with global health and environmental goals.

5.1. Conclusions

This meta-synthesis highlights nurses’ critical role in addressing climate change within healthcare, constrained by systemic barriers yet bolstered by actionable strategies. By fostering education, policy reform, and interdisciplinary collaboration, healthcare systems can empower nurses to lead sustainable practices, mitigating climate impacts and enhancing health equity. These findings call for concerted efforts to integrate sustainability into nursing practice, ensuring alignment with global health and environmental goals. Future research should explore quantitative measures of nurses’ sustainable practices to complement these qualitative insights, such as evaluating the impact of sustainability training on clinical outcomes. Comparative studies across diverse healthcare systems could elucidate context-specific barriers and facilitators. Additionally, longitudinal studies examining the efficacy of proposed strategies, such as curriculum integration or advocacy campaigns, would provide evidence for scaling interventions.