1. Background

The global rise in cesarean section rates has become a growing concern, with recent data indicating that nearly 50% of these procedures are elective (1). A nationwide study conducted in Iran between 2019 and 2021 on a sample of 230,870 women revealed that the cesarean section rate increased from 16.7% in 1998 to 21.5% in 2023 (2). In 2024, the cesarean section rate in Iran reached 56.6%, which was significantly higher than the global average. Moreover, in Isfahan province, the average cesarean section rate in public and private hospitals reached 62.5% in 2023 (3). According to the National Center for Health Statistics in the United States, approximately 80% of cesarean deliveries in 2021 were repeat procedures (4). Similarly, in Isfahan province, during 2024, repeat cesarean sections accounted for 68.5% of all cesarean births (3).

World Health Organization (WHO) aims to reduce cesarean section rates by minimizing the number of repeat cesarean sections among low-risk women (5). Vaginal birth after cesarean (VBAC) is a viable alternative to repeat cesarean delivery (6). The VBAC offers several advantages, including faster recovery, shorter hospital stays, reduced surgical risks, improved maternal-infant bonding, and lower rates of complications such as infection, thrombosis, and placental abnormalities. However, VBAC carries some risks, such as uterine rupture and the potential need for emergency cesarean delivery (7). Despite these risks, studies have shown that VBAC is generally safe and appropriate for many women (8).

Globally, VBAC rates range from 29% to 36% in countries such as Ireland, Italy, and Germany and from 45% to 55% in Finland, Sweden, and the Netherlands (9). In contrast, the VBAC rate in Iran during the first half of 2019 was less than 2% (approximately 1.73%), which is considerably lower than the global average (10). Between 1981 and 2020, reported VBAC success rates across Iran varied between 27% and 91.2% (11).

Despite its clinical importance, limited attention has been given to mothers’ experiences and satisfaction with planned VBACs. Maternal perceptions and satisfaction with previous birth experiences play crucial roles in determining the mode of delivery. However, assessing such subjective concepts remains challenging. A study conducted in Egypt (2023) reported that maternal satisfaction with VBACs was significantly influenced by psychological and physical support from the care team, active maternal participation in decision-making, and reduced prenatal anxiety. Most mothers described VBAC as a positive and empowering experience associated with a sense of control over childbirth, which led many mothers to recommend VBAC to other women with previous cesarean deliveries (12).

Similarly, a study revealed that women who received continuous midwifery care during pregnancy were more likely to attempt and successfully achieve VBAC. These women also received more counseling, reported greater satisfaction, and had more positive overall birth experiences than did those receiving fragmented models of care (13). Studies conducted in Iran and Indonesia further demonstrated that interventions — including childbirth preparation classes, individualized birth plans, enhanced mother-provider communication, family involvement, and emotional support during labor — significantly improve vaginal birth rates and maternal satisfaction (14, 15).

Previous research has focused primarily on interventions provided during either pregnancy or labor, with limited attention given to continuous and integrated support provided early in pregnancy through delivery (12). Furthermore, existing studies have examined maternal satisfaction in general, with little focus on satisfaction and outcomes related to VBACs (12).

Therefore, this study aims to fill this gap by implementing a comprehensive, multicomponent perinatal intervention designed to increase maternal satisfaction and promote successful VBAC throughout the perinatal period. Assessing maternal satisfaction after successful VBAC may provide evidence to inform strategies and policies aimed at reducing unnecessary repeat cesarean deliveries.

2. Objectives

The present study aimed to evaluate the effect of a multicomponent perinatal intervention on maternal satisfaction following vaginal delivery after cesarean section.

3. Methods

This study was a randomized controlled clinical trial (IRCT20091219002889N14) conducted at Amin Hospital, Isfahan, Iran, from March 2024 to March 2025. Ethical approval was obtained from the Ethics Committee of Isfahan University of Medical Sciences (IR.MUI.NUREMA.REC.1401.175). This trial was conducted as part of the first author’s doctoral dissertation in reproductive health.

3.1. Inclusion Criteria

The inclusion criteria were as follows: Iranian nationality; residence in Isfahan; gestational age between 18 and 23 weeks; history of only one previous cesarean section; absence of mental disorders; maternal age under 40 years; normal maternal vital signs; no history of intrauterine fetal death (IUFD); absence of medical indications for cesarean delivery, such as prolonged labor, breech presentation, or fetal distress; singleton pregnancy; no history of placenta previa; transverse uterine incision in the previous cesarean; normal Body Mass Index (BMI: 19.8 - 24) at the first prenatal visit (16); spontaneous conception (nonassisted pregnancy); interpregnancy interval of at least 18 months between the previous cesarean and current pregnancy (17); and absence of any medical condition deemed by the VBAC team as a contraindication to vaginal delivery.

3.2. Exclusion Criteria

The exclusion criteria included unwillingness to continue participation at any stage; maternal or fetal complications during pregnancy contraindicating vaginal delivery as determined by the VBAC team; requirement for emergency cesarean section; irregular attendance (missing more than three consecutive intervention sessions); nonreactive nonstress test (NST) results after 28 weeks; placental adhesion or abnormal placental function on Doppler ultrasound; failure of spontaneous onset of labor; estimated fetal weight > 3.5 kg; and evidence of pelvic stenosis; and participation in childbirth preparation classes among women in the control group.

3.3. Sample Size

The sample size was calculated on the basis of the maximum variance between the intervention and control groups, with a significance level of α = 0.05 and a statistical power of 80%. In accordance with the findings of Zarabi Jourshari et al. (18), with the parameters α = 0.05, β = 0.20, Zα/2 = 1.96, Zβ = 0.84, S12 = 8.2, S22 = 9.9, μ1 = 39.1, and μ2 = 44.2, the minimum required sample size was estimated to be 25 participants per group. To account for potential attrition and ensure adequate statistical power, the sample size was increased to 50 participants per group (19). The sample size formula was as follows:

3.4. Sampling, Randomization, and Trial Procedures

Eligible participants were identified via the hospital’s pregnancy registration system. Women with a history of one previous cesarean section were contacted by telephone and invited to participate. After the inclusion criteria were verified and the study objectives and procedures were explained, written informed consent was obtained.

The participants were randomly allocated to the intervention or control group via a permuted block randomization method (block size = 2) at a 1:1 ratio. A total of one hundred sealed, opaque envelopes labeled with codes “A” and “B” were prepared. Allocation concealment was ensured through the random distribution of envelopes by lot drawing. Randomization was performed by an independent statistician. Blinding of participants and care providers was not feasible due to the nature of the intervention.

3.5. Outcome Measures

The primary outcome was maternal satisfaction and its subscales. The secondary outcome was the rate of VBAC.

Maternal satisfaction was assessed via the Birth Satisfaction Scale (BSS), which comprises two parts: One for vaginal birth and one for cesarean birth. Each part includes ten dimensions covering the maternal perception of healthcare personnel, midwifery care, comfort, participation in decision-making, postpartum care, privacy, and fulfillment of expectations (20). The Persian version of both parts of the questionnaire was validated by Pakari et al. (21), confirming its content validity (CVI = 0.79, CVR = 0.75), construct validity (via confirmatory factor analysis), and reliability (Cronbach’s α = 0.89 for the vaginal birth part and α = 0.84 for the cesarean section part) (21). The scale includes 41 items rated on a 5-point Likert scale (1 = strongly disagree to 5 = strongly agree). Total scores range from 41 - 205 and are categorized as low (41 - 95.67), moderate (95.68 - 150.34), or high (150.35 - 205) (20, 21). In our study, test-retest reliability was evaluated in 25 participants, resulting in a correlation coefficient of 0.87, indicating good reliability.

3.6. Intervention

Following an extensive literature review, a multidisciplinary VBAC program was developed by a team comprising an obstetrician-gynecologist, reproductive health specialist, anesthesiologist, neonatologist, sonographer, midwives, and companion midwife. The intervention consisted of counseling sessions, supplementary prenatal visits, acupressure therapy, and delivery at a specialized birth center.

After ethical approval and informed consent were obtained, participants were recruited between 18 and 23 weeks of gestation. The intervention group attended eight 90-minute sessions beginning between 20 and 23 weeks of gestation, whereas the control group received standard prenatal care only. The start of childbirth preparation classes during these weeks is recommended for several reasons: To reduce the risk of miscarriage after this period, to increase the mother’s energy and physical fitness, and to provide sufficient time to learn and practice childbirth skills (22, 23).

These sessions were supervised by a reproductive health specialist and three midwives and included educational, counseling, and practical components. The participants were divided into 10 groups of 5 mothers each. The sessions provided both group and individual instructions, covering topics such as prenatal and medical care, childbirth procedures and preparation, nutrition, physical exercise, relaxation, and breathing techniques. In addition to the routine topics covered in physiologic childbirth preparation, these sessions emphasized the benefits, risks, and clinical considerations associated with VBACs. Individualized counseling was also provided to support mothers in making informed and confident decisions regarding their preferred mode of delivery (Table 1). Each session was allocated approximately 45 minutes to practical exercises. The attendance of the husband was mandatory in at least one session.

| Counseling Sessions 45-Minute Theoretical Session and 45-Minute Practical Session | Prenatal Visits | |

|---|---|---|

| Sessions Time | Meeting Content | |

| First meeting with husband 20 - 23 weeks | Anatomical and physiological changes during pregnancy, common complaints during pregnancy, the concept of vaginal delivery after cesarean section, the concept of repeated cesarean section, complications of repeated cesarean section, benefits and complications of vaginal delivery after cesarean section, percentage of failure and success of vaginal delivery after cesarean section, contraindications of vaginal delivery after cesarean section; Stretching exercises, relaxation, and breathing | 20 w |

| Second session 24 - 27 weeks | Review of previous session, pregnancy care, danger signs, stretching exercises, relaxation, and breathing | 24 w |

| Third session 28 - 29 weeks | Pregnancy nutrition, mental health, stretching, relaxation, and breathing exercises | 28 w: Performing a NST |

| Fourth session 30 - 31 weeks | Labor pain and methods for reducing labor pain; Stretching, relaxation, and breathing exercises | 32 w: Requesting for ultrasound of uterine thickness and placental adhesions |

| Fifth session 32 - 33 weeks | Understanding the stages of labor and the different positions of labor, necessary interventions during labor; Stretching, relaxation, and breathing exercises | 36 w |

| Sixth session 34 - 35 weeks | Explaining the importance of vaginal delivery and reviewing methods for reducing pain and the stages of labor, the role of the midwife, planning for delivery, showing a vaginal delivery video, stretching, relaxation, and breathing exercises | 37 w: Performing pelvic examination, pelvic dimensions, fetal weight estimation and birth plan determination |

| Seventh session 36 weeks | Pregnancy danger signs, postpartum care, and postpartum danger signs | 38 w |

| Eighth session 37 weeks | A review of birth planning, family planning, preparation of other family members, newborn care, and newborn danger signs; Obtaining informed consent for vaginal delivery after cesarean section from the mother and partner; Stretching, relaxation, breathing exercises, and acupressure training | 39 w |

Abbreviation: NST, nonreactive nonstress test.

In addition to routine care, participants received at least eight supplementary visits conducted by midwives and obstetricians at the specialized VBAC clinic between 20 and 40 weeks of gestation. At 28 weeks, the participants underwent a NST. At 36 weeks, an ultrasound was performed to assess lower uterine segment thickness (24), followed by a pelvic examination at 37 weeks to confirm the feasibility of vaginal delivery.

After confirming VBAC eligibility, acupressure was administered at 37 weeks by a certified midwife. Two points were used: BL32 (Ciliao) and GB30 (Huantiao).

BL32, located in the sacral region, is associated with uterine stimulation and facilitates labor onset. GB30, located near the sciatic notch, promotes pelvic relaxation, alleviates labor pain, and facilitates fetal descent.

Acupressure was applied twice for 2 minutes at 20-minute intervals (25, 26) under the supervision of a national instructor of physiological childbirth, who is a certified midwife. The mother’s partner was trained to apply acupressure five times per hour daily (25) until the onset of labor, maintaining consistency under professional supervision.

The participants in the intervention group were delivered at the specialized VBAC center under continuous supervision by the research team. Labor is managed physiologically without invasive methods. The control group received routine obstetric care.

Postpartum, both groups completed the maternal satisfaction questionnaire 7 - 10 days after delivery.

3.7. Ethics Approval and Consent to Participate

The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Isfahan University of Medical Sciences (IR.MUI.NUREMA.REC.1401.175) and was conducted in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. All participants were thoroughly informed about the objectives, procedures, and voluntary nature of the research. They were assured of their right to withdraw from the study at any stage without any consequences and were guaranteed full confidentiality and anonymity of their data.

Written informed consent was obtained from all participants prior to enrollment. The research team — comprising an obstetrician-gynecologist, a reproductive health specialist, and a midwife — was available 24 hours a day to address any questions raised by the participants. In addition to providing consent for general study participation, women in the intervention group, together with their husbands, provided written informed consent to consider VBAC as an option, in accordance with standard clinical guidelines.

3.8. Statistical Analysis

The data are described via descriptive statistics, with means and standard deviations for quantitative variables and frequencies and percentages for qualitative variables. To compare outcomes between groups, parametric tests (independent samples t-test or one-way ANOVA) were applied when the assumptions of normality and homogeneity of variance were met. The normality of the data was assessed via the Shapiro-Wilk test, and the homogeneity of variance was evaluated via Levene’s test. In cases where these assumptions were not satisfied, the corresponding nonparametric alternatives were used, namely, the Mann-Whitney U test for two-group comparisons and the Kruskal-Wallis test for comparisons across more than two groups. To account for potential confounding variables, we performed adjusted analyses in addition to the unadjusted group comparisons. The outcomes were analyzed via analysis of covariance (ANCOVA), with the group variable entered as the main predictor and relevant baseline significant characteristics between the two groups included as covariates. All analyses were performed at a 5% error level via SPSS version 20 software. For the mothers who withdrew from the study, a per-protocol (PP) approach was applied.

4. Results

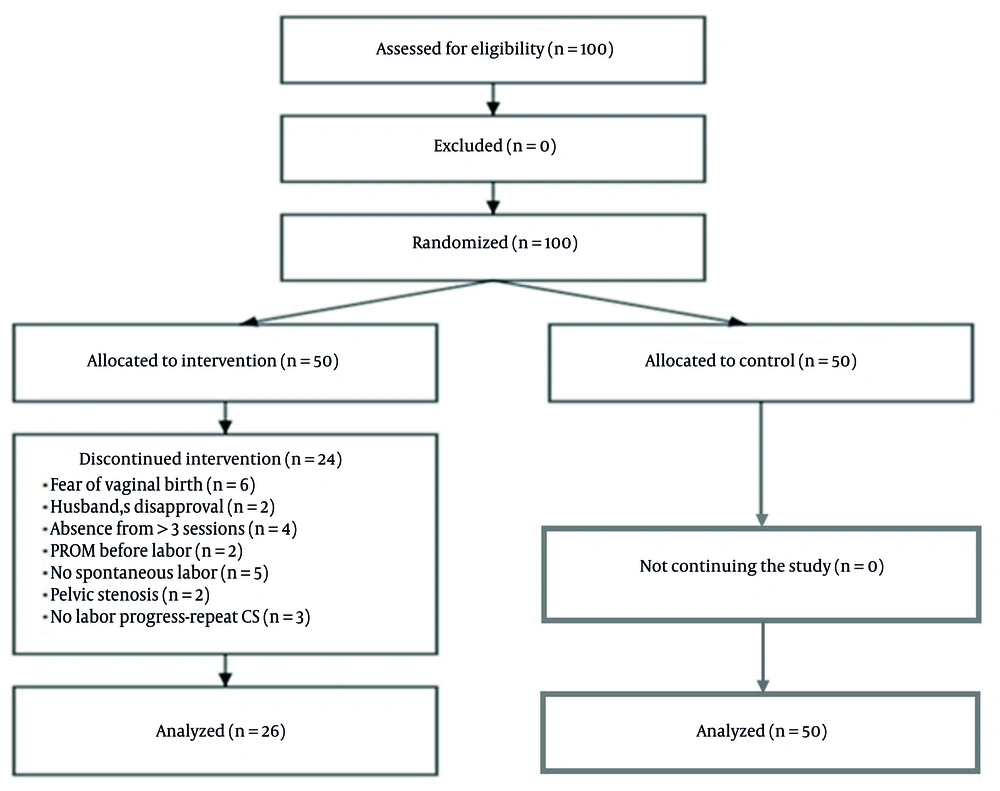

There were 24 dropouts in the intervention group, and the final analysis was performed on 26 participants. There were no dropouts in the control group (Figure 1).

4.1. Participant Characteristics

The demographic and obstetric data for the mothers are presented in Table 2. The normality of continuous variables was assessed via the Shapiro-Wilk test. Age, number of pregnancies, number of deliveries, and number of living children were normally distributed and analyzed via the independent samples t-test. The number of abortions and number of stillborn children were not normally distributed and were analyzed via the Mann-Whitney U test.

| Variables | Control | Prenatal Intervention | P-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Qualitative characteristics | |||

| Education | 0.02 b | ||

| Illiterate | 0 (0) | 8 (30.80) | |

| Primary | 1 (2.00) | 9 (34.60) | |

| Diploma-secondary | 7 (14.00) | 8 (30.80) | |

| University | 42 (84.00) | 1 (3.80) | |

| Employment status | 0.19 b | ||

| Unemployed | 21 (42.00) | 14 (53.80) | |

| Nongovernment | 10 (20.00) | 4 (15.40) | |

| Corporate | 8 (16.00) | 5 (19.20) | |

| Contractual | 8 (16.00) | 2 (7.70) | |

| Official | 3 (6.00) | 1 (3.80) | |

| Type of previous delivery | 0.63 c | ||

| Vaginal | 0 (0) | 2 (7.70) | |

| Cesarean section | 50 (100) | 24 (92.30) | |

| Quantitative characteristics | |||

| Age (y) | 33.62 ± 5.21 | 34.45 ± 4.31 | 0.28 d |

| Number of pregnancies (count) | 2.41 ± 1.02 | 2.53 ± 2.11 | 0.73 d |

| Number of deliveries (count) | 1.33 ± 0.50 | 2.35 ± 0.20 | 0.65 d |

| Number of abortions (count) | 0.46 ± 0.40 | 0.28 ± 0.42 | 0.40 e |

| Number of stillborn children (count) | 0.10 ± 0.30 | 0.15 ± 0.13 | 0.64 e |

| Number of living children (count) | 1.20 ± 0.60 | 1.30 ± 0.50 | 0.33d |

a Values are expressed as No. (%) or mean ± SD.

b Chi-square test.

c Fisher’s exact test.

d Independent t-test.

e Mann-Whitney U test.

The results of the Mann-Whitney test indicated that although there were no statistically significant differences in most demographic characteristics between the two groups, education level differed significantly (P = 0.02). Among the 50 eligible participants, 38 received the intervention and were followed up. Of these, 12 were excluded for clinical reasons, and 26 of the total 50 participants (26/50, 52%) achieved a successful VBAC in the intervention group, whereas no participants in the control group achieved VBAC (0/50, 0%). The difference between groups was statistically significant (Fisher’s exact test, P = 0.048).

4.2. Childbirth Satisfaction Score

Total satisfaction was analyzed via ANCOVA, controlling for the following potential confounders: Age, education level, number of pregnancies, number of deliveries, previous delivery type, and employment status. Satisfaction subscales were analyzed via MANCOVA, followed by post hoc ANCOVA for each subscale, controlling for the same covariates. The adjusted means and statistical results are presented in Table 3.

| Satisfaction Subcategories | Prenatal Intervention | Control | F-Value | P-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Staff behavior | 16.12 ± 3.28 | 17.40 ± 2.71 | 2.10 | 0.14 b |

| Care in the department | 8.10 ± 1.80 | 8.12 ± 1.88 | 0.12 | 0.84 b |

| Peace and comfort | 10.81 ± 2.56 | 10.80 ± 2.65 | 0.01 | 0.60 b |

| Participation | 30.1 ± 5.50 | 32.00 ± 6.21 | 4.50 | 0.018 b |

| Baby care | 12.44 ± 2.20 | 11.00 ± 3.77 | 1.75 | 0.81 b |

| Delivery room | 22.50 ± 5.00 | 25.25 ± 4.19 | 0.55 | 0.77 b |

| Postpartum care | 11.90 ± 2.70 | 12.79 ± 2.31 | 9.05 | 0.003 b |

| Department facilities | 11.20 ± 2.87 | 11.77 ± 2.87 | 0.53 | 0.47 b |

| Privacy | 9.54 ± 3.07 | 10.39 ± 3.25 | 0.39 | 0.54 b |

| Expectations | 18.08 ± 2.40 | 18.29 ± 4.13 | 1.70 | 0.19 b |

| Total | 163.15 ± 22.45 | 157.68 ± 20.45 | 0.30 | 0.58 c |

a Values are expressed as mean ± SD.

b MANCOVA.

c ANCOVA.

The results revealed no significant differences between the intervention and control groups in overall satisfaction and most subscales, except for postpartum care (P = 0.003) and participation in the childbirth process (P = 0.018), which were statistically significant.

The normality of the total satisfaction score was confirmed via the Shapiro-Wilk test (P = 0.12), and the homogeneity of variance was verified via Levene’s test (P = 0.45). All assumptions for ANCOVA were therefore satisfied.

5. Discussion

In the present study, no significant differences were observed in overall maternal satisfaction scores or in most subscales between the control and intervention groups. However, a statistically significant difference was found in the postpartum care and participation subscale in favor of the VBAC group. This finding may be attributed to the combination of physiological and psychosocial benefits inherent to VBACs. Women who underwent VBAC typically reported faster physical recovery, fewer anesthesia-related complications, reduced postoperative pain, and improved communication with healthcare providers.

Comparisons with previous studies yielded different results. Studies conducted in Turkey and Egypt reported greater maternal satisfaction following VBAC (27, 28), whereas a study in Iran reported no significant difference in maternal satisfaction between the VBAC and repeat cesarean groups, which is consistent with our findings (29). Similarly, a study in the United Kingdom involving 170 women attempting VBAC reported a 68.8% success rate in terms of vaginal birth and no significant difference in maternal satisfaction (30). These discrepancies may be attributed to differences in sample characteristics, cultural context, assessment tools, or confounding factors such as previous vaginal delivery history and maternal education. The active involvement of women in decision-making may mitigate the influence of delivery mode on maternal satisfaction by enhancing a sense of control, autonomy, and ownership over the birth experience. Cultural and social factors may also play a role in shaping maternal satisfaction (31).

A commonly cited reason for high satisfaction following cesarean delivery is the avoidance of labor pain (32, 33). In our study, despite common fears and anxiety associated with vaginal birth, overall satisfaction among VBAC participants was comparable to that of women undergoing repeat cesarean delivery. Furthermore, satisfaction with postpartum care was significantly greater in the VBAC group. These findings are consistent with studies conducted in Greece, Egypt, and Turkey, highlighting that comprehensive supportive care can increase maternal satisfaction across diverse populations (27, 28, 34).

Emerging evidence suggests that individual maternal characteristics — such as prior childbirth experiences, levels of awareness, and familiarity with the birthing process — may shape women’s perceptions and overall satisfaction with childbirth, a pattern also noted in previous Iranian research (35). Furthermore, high maternal satisfaction has been consistently associated with supportive intrapartum care models and the active involvement of a multidisciplinary care team, as demonstrated in earlier studies from Iran (36, 37). Such collaborative and woman-centered approaches can enhance mothers’ feelings of safety, confidence, and empowerment during labor, thereby contributing to greater satisfaction irrespective of the mode of delivery.

The VBAC success rate was 52% in our study, whereas rates reported in other studies ranged from 41% to 79% across different populations (38-43). This variability may be due to differences in maternal selection criteria, institutional policies, provider attitudes, intrapartum management practices, population characteristics, and psychological factors such as maternal awareness and confidence.

Despite the study’s limitations, including the inability to blind participants and unmeasured maternal fear and anxiety, our findings indicate that with appropriate education, support, and multidisciplinary care, VBAC can serve as a safe and satisfactory alternative to repeat cesarean delivery, achieving high maternal satisfaction irrespective of delivery mode.

5.1. Conclusions

The findings of this study indicated that although there was no statistically significant difference in overall maternal satisfaction between women who underwent planned VBAC and those with repeat cesarean section, both groups reported high satisfaction levels. This suggests that the quality of care, effective communication, and active maternal participation in decision-making may play a more crucial role in determining satisfaction than the mode of delivery itself does.

Maternal satisfaction should therefore be regarded as a key indicator for evaluating the quality of childbirth services. Policymakers and healthcare providers seeking to minimize complications associated with repeat cesarean deliveries should promote evidence-based strategies that encourage safe VBAC when clinically appropriate. In particular, implementing interventions such as structured prenatal counseling and continuous emotional support can increase maternal satisfaction and overall well-being, regardless of the chosen delivery method.