1. Background

Urinary tract infections (UTIs) are among the most common bacterial infections in infants and young children and, if not promptly and accurately diagnosed, may result in serious complications, including renal scarring, recurrent episodes, and long-term hypertension (1, 2). Accurate diagnosis requires a minimally contaminated urine specimen for laboratory evaluation of leukocytes, red blood cells (RBCs), epithelial cells, and bacteria (3).

Current urine collection approaches in non-toilet-trained infants fall into invasive and non-invasive categories. Invasive methods such as transurethral catheterization and suprapubic aspiration provide low contamination rates but cause significant discomfort, require trained personnel, and may be unacceptable to caregivers (4, 5). Conversely, urine-collection bags are widely used due to their noninvasive nature, yet they carry contamination rates as high as 60 - 80% because of contact with perineal skin flora, often leading to false-positive results and unnecessary antibiotic prescriptions (6-8).

To address these challenges, noninvasive stimulation-based clean-catch techniques have been proposed. The Quick-Wee method involves cleaning the suprapubic area and gently stimulating it with cold, wet gauze to elicit a cutaneous voiding reflex. Initial studies suggest that Quick-Wee can trigger urination in a substantial proportion of infants within a few minutes, providing a faster and less invasive option compared to standard practices (9-11). However, evidence comparing its contamination profile against the commonly used urine bag method — particularly through quantitative microscopy endpoints — remains scarce, and most prior studies have employed between-subject designs subject to confounding.

Minimizing contamination is not only essential for diagnostic accuracy but also critical to reducing inappropriate antibiotic use, a key driver of antimicrobial resistance (12, 13). Reliable and rapid noninvasive techniques such as Quick-Wee may therefore improve diagnostic confidence, reduce overtreatment, and enhance caregiver and clinician satisfaction, especially in settings where invasive procedures are impractical or poorly accepted (14, 15). Despite the growing use of the Quick-Wee technique in clinical settings, evidence directly comparing its contamination profile with conventional urine-collection bags, particularly through quantitative microscopy endpoints, remains limited. Existing studies often rely on between-group designs, which are prone to interindividual variability.

2. Objectives

Therefore, a within-subject randomized crossover design can more accurately determine whether Quick-Wee truly offers superior sample cleanliness, shorter collection time, and higher caregiver satisfaction under routine hospital conditions. Addressing this evidence gap is crucial for optimizing diagnostic accuracy in non-toilet-trained infants, minimizing unnecessary antibiotic use, and improving procedural comfort for both children and caregivers.

3. Methods

3.1. Study Design and Setting

We conducted a randomized, two-period, two-sequence (AB/BA) within-subject crossover study in which each infant underwent both urine-collection methods and thus served as his or her own control. The study was carried out in the Pediatric Ward of Heshmatiyeh Hospital, Sabzevar, Razavi Khorasan province, Iran, during 2021 - 2022.

3.2. Participants

The target population comprised hospitalized, non-toilet-trained infants who required urine testing as part of routine clinical care.

- Inclusion criteria: Age 1 - 23 months; clinical indication for urinalysis; written informed consent from a parent/guardian.

- Exclusion criteria: Known urogenital anomalies; antibiotic administration before urine collection; any condition that precluded proper adherence to the standard operating procedure (SOP).

3.3. Sampling, Randomization, Allocation, and Blinding

Eligible infants admitted to the pediatric ward were consecutively screened and enrolled after obtaining written parental consent. For each participant, the order of urine-collection methods was randomly assigned as AB (Quick-Wee followed by urine bag) or BA (urine bag followed by Quick-Wee). Randomization was generated by a computer-based list and implemented using sequentially numbered, opaque, sealed envelopes (SNOSE) prepared by an independent researcher not involved in data collection. Both urine collections for each infant were performed by the same trained pediatric nurse, who had completed a standardized workshop and practiced both methods under supervision before the study began. To prevent cross-contamination or carry-over between the two periods, the diaper was changed, and the peri-urethral/genital area was washed with clean water and completely dried before each collection. Laboratory staff were blinded to both the method and the sequence of collection. Each urine sample was labeled with a unique anonymized code to ensure masking during analysis.

3.4. Intervention Protocols and Timing

Each infant provided two urine samples: The first at the start of a clinical shift and the second approximately 6 hours later (end of the same shift) as a pragmatic washout. Before each collection, the diaper was changed, and the perineal/meatal area was washed with clean water and gently dried.

3.4.1. Quick-Wee Method

Before stimulation, the infant was placed in a semi-recumbent position on a clean examination surface, with a sterile absorbent pad underneath. The suprapubic region was exposed and gently cleaned with sterile water and allowed to air-dry. A piece of sterile gauze (approximately 5 × 5 cm) was soaked in cold water maintained at 10 - 15°C, squeezed to remove excess fluid, and applied to the suprapubic skin in a gentle circular motion. The stimulation continued for up to 5 minutes until spontaneous voiding occurred. Once voiding began, the initial urine stream was allowed to pass for approximately one second to minimize external contamination, after which a clean-catch midstream sample was collected directly into a sterile screw-cap container without touching the perineum or container rim. If no urine was passed within 5 minutes, the attempt was recorded as unsuccessful.

3.4.2. Urine-Bag Method

Following identical pre-cleaning of the perineal area with sterile water and air-drying, a single-use sterile adhesive urine-collection bag appropriate for the infant's gender was applied. The bag was positioned to cover the urethral opening securely while minimizing contact with surrounding skin folds. The infant’s diaper was replaced loosely to hold the bag in place while allowing visual monitoring. The collection was observed every 5 minutes for up to 60 minutes. Once urination occurred, the bag was immediately removed, and urine was transferred aseptically into a sterile container using gloved hands. If no voiding occurred within 60 minutes, the attempt was considered unsuccessful and recorded as such.

For both methods, all specimens were immediately labeled with anonymized study codes and transported to the laboratory within 15 minutes of collection for microscopic analysis.

3.5. Outcomes

3.5.1. Primary Outcomes

Quantitative urine microscopy counts of white blood cells (WBCs), RBCs, epithelial cells, and bacteria on urine smear [reported as cells/high-power field (HPF) or laboratory semi-quantitative categories]. No urine culture was performed; contamination was assessed exclusively by light microscopy. Since these indices are part of routine laboratory diagnostics, their validity and reliability are established by standardized laboratory protocols and internal quality-control procedures.

3.5.2. Secondary Outcomes

Time to successful collection, measured objectively in minutes with a stopwatch. This measure has inherent reliability due to its direct nature. Caregiver satisfaction was assessed using a researcher-developed 5-point Likert scale (1 = very dissatisfied to 5 = very satisfied). As satisfaction was measured with a single-item Likert scale, internal consistency (Cronbach’s α) was not applicable. However, expert review and pilot testing supported the face and content validity of the measure.

3.6. Sample Size Calculation

Sample size was calculated for a paired design using the standard formula for the paired t-test:

where n is the number of pairs (infants), Δ is the expected mean paired difference in microscopy counts, σd is the standard deviation of paired differences,

3.7. Statistical Analysis

All statistical analyses were conducted using SPSS version 26 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY). To evaluate the microscopy outcomes — including WBC, RBC, epithelial cell, and bacterial counts — a linear mixed-effects model was employed, treating participant ID as a random effect and the urine-collection method (Quick-Wee vs. bag), study period (first or second), and sequence (AB or BA) as fixed effects. The interaction term between method and period was examined to assess any potential carry-over effect. To maintain control of the family-wise type I error rate across the four primary outcomes, Bonferroni correction was applied, yielding an adjusted significance threshold of α = 0.0125.

For collection-time comparisons, approximate normality of within-pair differences was verified, after which paired sample t-tests were used. Caregiver-satisfaction scores, collected on a 5-point Likert scale, were analyzed using the Wilcoxon signed-rank test because of their ordinal distribution. All analyses were two-tailed, and results were reported as effect sizes or paired mean/median differences with corresponding 95% confidence intervals (CIs).

3.8. Ethical Considerations

The study protocol was approved by the Committee of Sabzevar University of Medical Sciences (IR.MEDSAB.REC.1399.172). Written informed consent was obtained from parents/guardians, and data confidentiality was maintained through anonymized coding.

4. Results

4.1. Participants

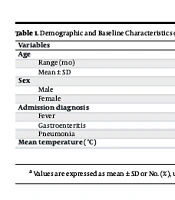

A total of 105 infants were enrolled in the study, including 57 males (54.3%) and 48 females (45.7%), aged between 1 and 23 months (6.4 ± 3.7 months). The most common admission diagnoses were fever in 44 infants (41.7%), pneumonia in 44 infants (41.7%), and gastroenteritis in 18 infants (16.7%). All infants underwent urine collection using both the Quick-Wee and urine bag methods, with no samples excluded from the analysis. The demographic and clinical characteristics of the study population are summarized in Table 1.

| Variables | Values |

|---|---|

| Age | |

| Range (mo) | 1 - 23 |

| Mean ± SD | 6.4 ± 3.7 |

| Sex | |

| Male | 57 (54.2) |

| Female | 48 (45.8) |

| Admission diagnosis | |

| Fever | 44 (41.7) |

| Gastroenteritis | 18 (16.7) |

| Pneumonia | 44 (41.7) |

| Mean temperature (°C) | 37.28 ± 0.40 |

a Values are expressed as mean ± SD or No. (%), unless otherwise indicated.

4.2. Contamination Markers

In the analysis of contamination markers, linear mixed-effects models revealed significantly lower contamination levels in Quick-Wee samples compared to urine bag samples for all measured cellular markers, including WBC, RBC, and epithelial cells (P < 0.0125 after Bonferroni adjustment; Table 2). No significant difference was observed for bacterial contamination (P = 0.096). Interaction and carry-over effects were non-significant (P ≥ 0.08 for both), indicating no methodological bias in the paired analysis.

| Marker/Effects | Quick-Wee (Mean ± SD) | Urine Bag (Mean ± SD) | Mean Difference (95% CI) | Bonferroni Adjusted P-Value | Interaction P-Value | Carry-Over P-Value | ICC |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| WBC (cells/HPF) | 1.0 ± 0.0 | 2.2 ± 0.9 | -1.19 (-1.57, -0.81) | < 0.001 | ≥ 0.08 | ≥ 0.08 | 0.44 |

| RBC (cells/HPF) | 1.0 ± 0.2 | 1.3 ± 0.6 | -0.32 (-0.55, -0.09) | 0.007 | ≥ 0.08 | ≥ 0.08 | 0.33 |

| Epithelial (cells/HPF) | 1.0 ± 0.3 | 3.0 ± 2.0 | -1.78 (-2.22, -1.34) | < 0.001 | ≥ 0.08 | ≥ 0.08 | 0.48 |

| Bacterial contamination | 1.0 ± 0.588 | 1.208 ± 0.588 | -0.208 (-0.48, 0.07) | 0.096 | ≥ 0.08 | ≥ 0.08 | - |

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; ICC, intraclass correlation coefficient; WBC, white blood cell; HPF, high-power field; RBC, red blood cell.

a Microscopy units are cells/HPF for WBC, RBC, and epithelial cells; bacterial contamination is reported as a semi-quantitative score (0 - 3+).

b P-values are Bonferroni-adjusted (α = 0.0125).

4.3. Collection Time

A paired-sample t-test showed a 41.7-minute reduction in mean collection time for Quick-Wee compared with urine-bag collection (P < 0.001; Table 3).

| Methods | Mean ± SD (min) | P-Value |

|---|---|---|

| Urine bag | 52.4 ± 10.3 | < 0.001 |

| Quick-Wee | 10.7 ± 8.9 |

a Paired t-test was applied to compare mean times.

4.4. Caregiver Satisfaction

Caregiver satisfaction scores were significantly higher for Quick-Wee compared with urine bag collection (P < 0.001; Table 4). A larger proportion of parents rated their experience as “very satisfied” with Quick-Wee than with urine bag, while dissatisfaction was more common for urine bag collection.

| Satisfaction Scores | Quick-Wee | Urine Bag |

|---|---|---|

| Very dissatisfied (1) | 2 (1.9) | 15 (14.3) |

| Dissatisfied (2) | 4 (3.8) | 22 (21.0) |

| Neutral (3) | 10 (9.5) | 28 (26.7) |

| Satisfied (4) | 40 (38.1) | 25 (23.8) |

| Very satisfied (5) | 49 (46.7) | 15 (14.3) |

a Values are expressed as No. (%).

b Wilcoxon signed-rank test was applied for paired comparison.

4.5. Sensitivity Analyses

Excluding five infants who voided within 5 minutes of Quick-Wee stimulation did not materially change any outcome estimates, particularly the WBC difference (-1.19; 95% CI: -1.57 to -0.81). Results for RBC, epithelial cells, bacterial counts, collection time, and caregiver satisfaction were likewise unchanged (all inferences remained the same), confirming the robustness of our findings.

5. Discussion

5.1. Principal Findings

In this randomized AB/BA within-subject crossover study of hospitalized infants, the Quick-Wee technique yielded significantly lower microscopy counts of WBC, RBC, and epithelial cells compared with urine-bag collection, whereas bacterial counts did not differ significantly between methods (P = 0.096). Operationally, time to collection was approximately 42 minutes shorter with Quick-Wee, and caregiver satisfaction was higher (median 5 vs. 3). Taken together, Quick-Wee improved several microscopy-defined contamination markers and workflow metrics without a detectable difference in bacterial counts. The reduced contamination rates observed with Quick-Wee are consistent with prior reports demonstrating that non-invasive, clean-catch techniques can minimize exposure to perineal skin flora and, consequently, reduce false-positive urinalysis results (5, 7, 13).

Time efficiency is a major advantage of Quick-Wee. In our study, the mean collection time was approximately 41 minutes shorter than with the urine bag method. Additionally, our findings reinforce Quick-Wee’s acceptability in routine practice. A larger number of parents rated their experience as “very satisfied” compared to urine bag collection, likely reflecting both the reduced wait time and the less intrusive nature of the procedure. The results of the studies by Branagan et al., Kaufman et al., Herreros et al., Chandy et al., and Tullus et al. were similar to the present study (5, 9, 17-19).

The results of the study by Branagan et al. were similar to the results of our study. Branagan showed that 25% of infants in the intervention group voided urine 5 minutes after the intervention, while this figure was 18% in the control group. In their study, the time interval since the infant's last voiding and the effect of feeding before urine collection were not evaluated. Findings from their study differed from our study in terms of disease spectrum, population, and other interventions for sample collection (17).

In a study by Kaufman et al., gentle stimulation of the suprapubic skin using a gauze soaked in cold liquid (Quick-Wee method) significantly increased the rate of urination within five minutes and collected urine more quickly than standard urine collection (without additional stimulation). It also increased parental and physician satisfaction with this method. However, in their study, the difference in contamination rates between Quick-Wee and standard urine was not significant (P = 0.45) because the number of cultures available was lower. According to the authors, parents and physicians preferred the Quick-Wee method (5). Herreros et al. evaluated the stimulation of urination using the finger tap method. This study was limited by the lack of recording of time to urinate and the lack of a comparison group. The results of their study showed that the success rate of collecting clean urine within five minutes was 86%. They stated that cold thermal stimulation poses a risk of burns for sensitive skin. Their study showed that cold stimulation was more effective than stimulation at room temperature. They did not study infants in their research. They stated that stimulation of urination could reduce sample contamination more quickly and with greater force, but this did not mean that the results were statistically significant. Contamination of clean urine may be related to washing the foreskin or vagina and mixing with urine (18).

Tullus et al. conducted a study to compare the time of urine collection by Quick-Wee and the standard method. The results showed that the time to voiding was significantly faster in the Quick-Wee method compared to the standard method (P < 0.001). Parental and physician satisfaction was also higher with the Quick-Wee method. However, the probability of urine sample contamination was not statistically significant in either method. Therefore, neither method had a statistically significant difference in urine sample contamination. In other words, in this study, the contamination between the two methods was the same (19).

According to Kaufman et al., the clean urine collection method has the lowest contamination rate among noninvasive methods for children before reaching the stage of urinary incontinence. The clean urine collection method (Quick-Wee) is recommended by the American Nursing Association and has the lowest contamination rate among noninvasive methods. They stated that failure to collect a timely and accurate sample may delay effective treatment. Collection of a missed sample increases the likelihood of missed diagnosis and misdiagnosis (6).

The results of the study by Diviney et al. showed that clean sampling is less likely to be contaminated and can be made more efficient by stimulating urination in younger children. In an invasive test, suprapubic aspiration is less likely to be contaminated. This method has been reported to have a high success rate and low complication rate. However, it was painful and was not preferred by some parents (16). In other words, they were not completely satisfied with this method, which was different from our study in this regard.

The results of the study by Haid et al. showed that urine obtained via transurethral catheterization in uncircumcised boys is susceptible to contamination to a similar extent as bag urine (11).

Quick-Wee may lower microscopy indices by shortening time-to-void and enabling clean-catch immediately after standardized perineal cleansing, thereby reducing contact time/area with skin flora. The lack of a between-method difference in bacterial counts suggests that both methods can achieve comparable bacterial burdens under routine cleansing, or bacterial counts are less sensitive than cellular indices to procedural nuances. Clinically, a holistic interpretation of urinalysis integrating multiple microscopy parameters with the clinical picture remains essential.

5.2. Conclusions

Compared with urine-bag collection, Quick-Wee reduces several microscopy-defined contamination markers, markedly shortens time-to-collection, and improves caregiver satisfaction, while bacterial counts are similar between methods. These findings support Quick-Wee as a first-line non-invasive strategy for infant urine collection in routine care, with mindful interpretation of bacterial indices.

5.3. Strengths

Key strengths include the within-subject AB/BA crossover design (each infant as their own control), laboratory blinding, a pragmatic 6-hour spacing within one shift, and a standardized SOP for both methods.

5.4. Limitations

Limitations include reliance on microscopy counts without urine culture, potential residual period/carry-over effects despite modeling and spacing, single-center design, and a brief single-item satisfaction measure (face/content validity established; internal consistency not applicable to single-item tools).

5.5. Implications for Practice

In pediatric settings where invasive methods are impractical or unpopular, Quick-Wee offers a rapid, non-invasive option that improves several microscopy indices, streamlines collection by approximately 42 minutes, and enhances caregiver experience. Given the non-significant difference in bacterial counts, clinicians should interpret microscopy panels comprehensively and consider confirmatory testing when indicated.

5.6. Implications for Research

Future studies should examine the agreement between microscopy counts and culture in larger crossover cohorts, explore age- and feeding-related modifiers of time-to-void and contamination, and evaluate implementation outcomes (training, fidelity, costs) across diverse clinical settings.