1. Background

Hormone receptors belong to a class of proteins known as transmembrane receptors or intracellular receptors. Transmembrane receptors are embedded in the cell membrane and consist of an extracellular ligand-binding domain, a transmembrane domain, and an intracellular domain responsible for signal transduction (1-3). Intracellular receptors, on the other hand, are located within the cytoplasm or nucleus of the cell and are activated upon hormone binding. Hormone receptors exhibit high specificity for their respective ligands, allowing for precise control over cellular responses (4, 5). The binding of a hormone to its receptor triggers conformational changes, leading to the activation of downstream signaling pathways. These pathways can involve the activation of enzymes, gene transcription, or modulation of ion channels, depending on the specific receptor and hormone involved.

The development of drugs targeting hormone receptors requires a deep understanding of the atomic interactions between the receptor and its ligands. The goal is to design molecules that mimic or modulate the action of endogenous hormones, either by enhancing or inhibiting receptor activity (6-8). One key aspect of drug design is the identification of the binding site on the receptor. This is typically achieved through a combination of computational modeling techniques, such as molecular docking, molecular dynamics simulation (MDS), and virtual screening, as well as experimental methods like X-ray crystallography or nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy (9). These approaches provide valuable insights into the three-dimensional structure of the receptor and its ligand-binding pocket.

Once the binding site is identified, medicinal chemists can modify existing molecules or design new ones that interact with specific amino acid residues within the receptor's binding pocket. This can involve introducing chemical groups that enhance binding affinity or alter receptor selectivity. Structure-activity relationship studies are often performed to optimize drug potency and minimize off-target effects.

As reported before, the 7X9C neuropeptide Y is a peptide neurotransmitter that plays a key role in various physiological processes, including the modulation of appetite, regulation of energy homeostasis, and control of cardiovascular functions. This bio-structure affects energy expenditure by reducing the body's ability to burn calories through decreased physical activity and suppressed thermogenesis, which is the process by which the body generates heat and burns energy. This reduction in energy expenditure can further contribute to weight gain and the development of obesity.

Technically, the MD approach can indeed help identify new drug candidates that interact with ghrelin receptors (10, 11). Ghrelin is a peptide hormone that plays a key role in regulating appetite, energy balance, and growth hormone release. By using the MD method, researchers can study the atomic performance of ghrelin receptors under various conditions and in the presence of drug samples to design new treatments in clinical cases (12-15). Thus, MD outputs allow for a detailed understanding of how drugs bind to ghrelin receptors and modulate their activity, aiding in the design and optimization of novel drug compounds. Additionally, these simulations can provide insights into the thermodynamic stability and dynamics of bio-systems such as drug-ghrelin receptor complexes, which are crucial for predicting their effectiveness and potential side effects.

Chemically, atom-based simulations provide insights into the structural changes that occur upon drug binding to bio-systems. This information can aid in understanding the mechanism of action of the drug and guide further drug development efforts. Computationally, in MDS-based studies, the success of a drug in modulating hormone receptor activity hinges on its ability to form specific atomic interactions with the receptor. These interactions can be classified into several categories, including simple binding, electrostatic, and van der Waals interactions.

In the current research, we used the MD approach to predict the atomic evolution of the t-anethole drug in contact with 6KS0 adiponectin, 6H3E ghrelin, 8DHA leptin, and 7X9C neuropeptide Y hormone receptors for the first time. Trans-anethole (TA)'s pharmacophore features primarily include an aromatic ring that provides hydrophobic and π-π stacking interaction potential, and a methoxy group (-OCH3) attached to the aromatic ring, which acts as a hydrogen bond acceptor. The molecule's hydrophobic nature, due to its aromatic structure and methyl group, allows it to interact with hydrophobic pockets in biological targets. Additionally, the planar structure of the aromatic ring facilitates π interactions, while the electron-donating methoxy group modulates the electronic environment of the ring, enhancing binding affinity in some cases.

We expected the effect of drug interaction with leptin, adiponectin, and 7X9C neuropeptide Y to identify how different drugs or compounds interact with a target hormone (involved in regulating appetite and metabolism) and provide insights into the binding affinity and stability of the interaction. For this, various interactions, such as bound and unbound types, were defined inside a computational box at 300 K as the initial condition. We expected MD outputs to be used in drug design purposes in clinical applications. These results optimized the atomic interaction between the t-anethole drug and target receptors, which improves drug efficiency in treatment procedures.

1.1. Computational Approach Details

Molecular dynamics is based on the laws of classical mechanics, which describe the motion of particles in a system (16, 17). The basic idea is to numerically solve the equations of motion for each atom in the system, using a set of force fields that describe the interactions between atoms (18). These force fields are typically derived from experimental data and theoretical calculations. During the simulation, various properties of the system can be monitored, such as energy, temperature, pressure, and structural changes. These properties can be used to analyze the behavior of the system and to compare it with experimental data (Appendix 1 in Supplementary File).

Computationally, in this approach, Newton's formalism has been used for the estimation of the trajectories of the atoms through simulation time steps as formalism used (19).

Here, F represents the atomic net force, mi is the mass of atoms, r is the position of atoms, and v is the atom’s velocity. These equations are calculated via the velocity-Verlet approach to integrate Newton's formalism (20, 21). The current computational method has many applications in biostructures, including protein folding, protein-ligand binding, and membrane dynamics (18). In biostructures' time evolution, MD can be used to study the process by which a bio sample adopts its native conformation. This process involves the search for the lowest energy state among many possible conformations. Also, MD provides insights into the intermediate states and transition pathways involved in this process.

These capabilities of MD led us to use this approach to study the atomic interaction between the t-anethole drug and 6KS0 adiponectin, 6H3E ghrelin, 8DHA leptin, and 7X9C neuropeptide Y hormone receptors. To estimate atomic interactions between various samples inside the computational box, the DREIDING force field was used (22). The DREIDING force field has notable limitations in accuracy for aromatic systems like t-anethole, mainly due to its generic parameterization approach. It uses van der Waals parameters and charges that do not fully capture the specific electronic and polarizability characteristics of aromatic rings and their substituents. However, the appropriate coefficients of this force field have caused the DREIDING potential to have acceptable performance in the description of biostructures' time evolution. In this force field, the non-bond interaction is defined by the formalism (Lennard-Jones potential) (23):

Furthermore, the various bond interactions are defined with simple harmonic formalism:

In details, these formulations implemented for simple and angular bonding, respectively (24). By using these interaction formalisms, MD followed two main steps. Firstly, modeled atomic systems were equilibrated at 300 K as the initial condition (with a damping ratio of 10). This equilibrium phase was conducted for 10 ns. The kinetic and total energy of samples were calculated to report the equilibrium phase. Next, the NVT ensemble converged to the NVE one, and MD continued for an additional 10 ns. In this step, the interaction between the t-anethole drug and various target hormone receptors was estimated with calculations of enthalpy, binding, coulombic, van der Waals, and potential energies.

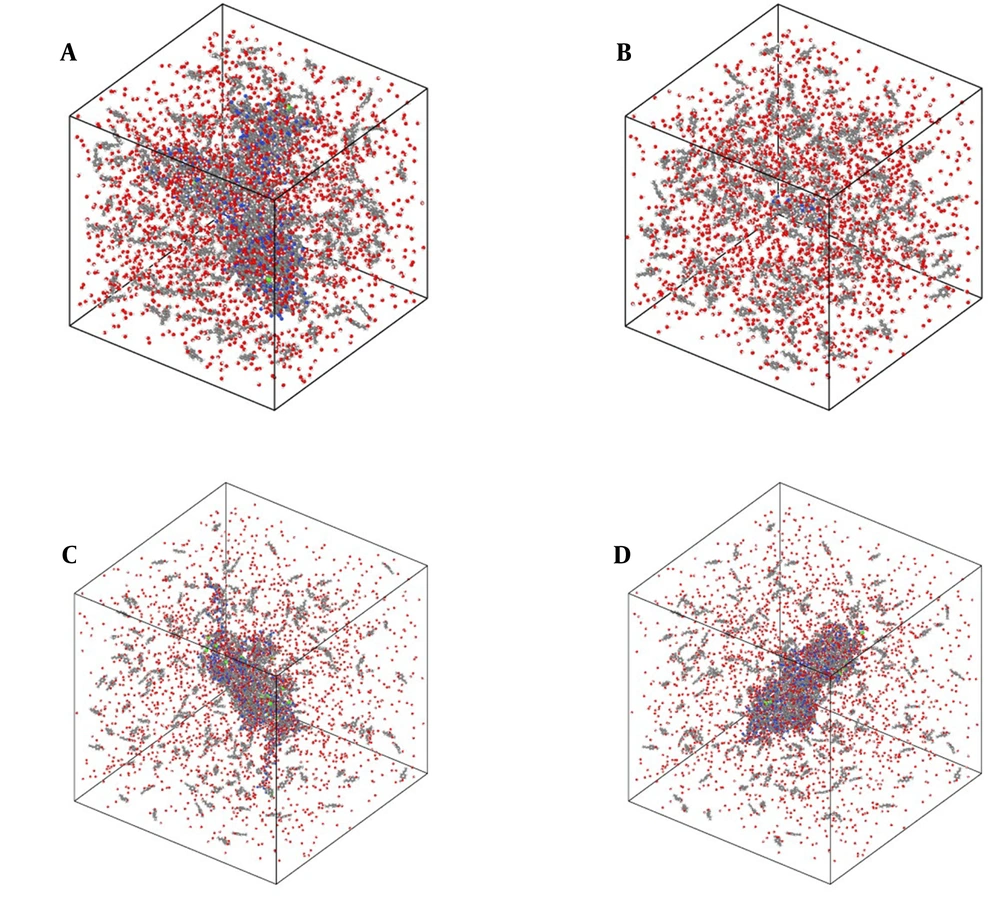

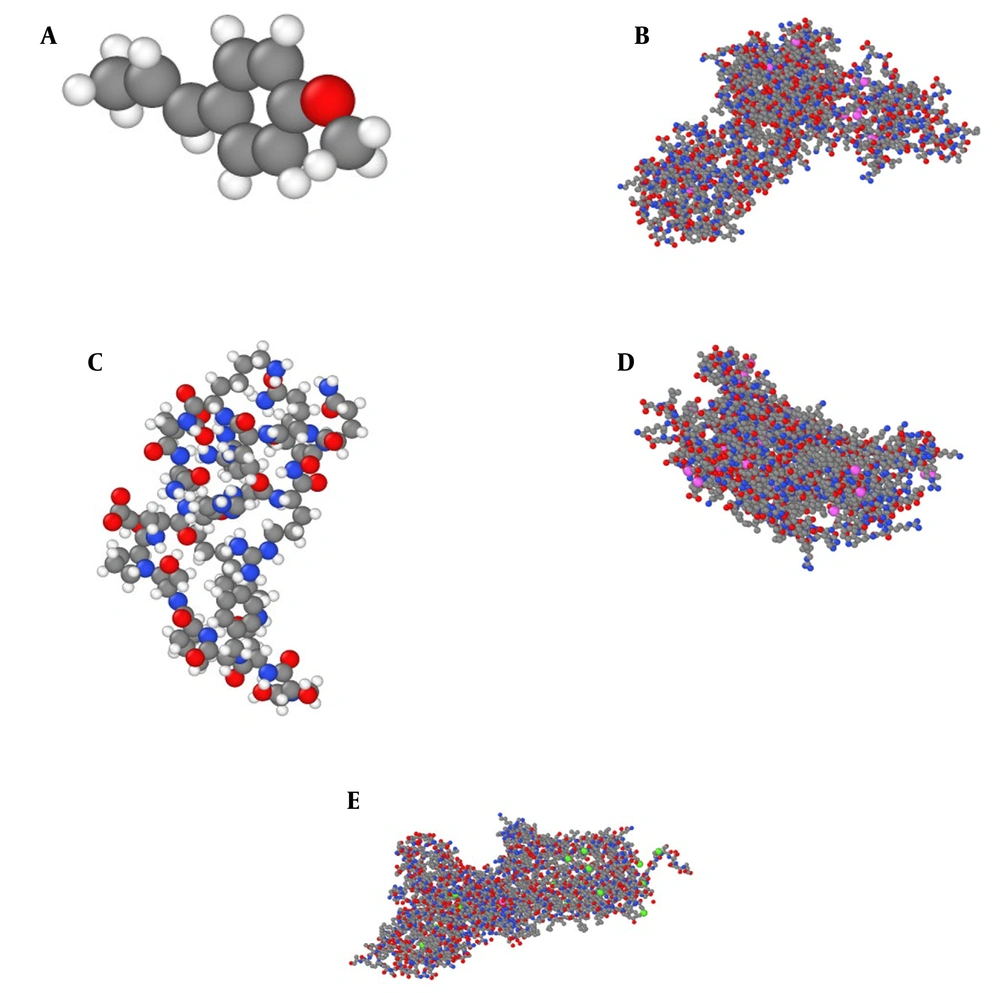

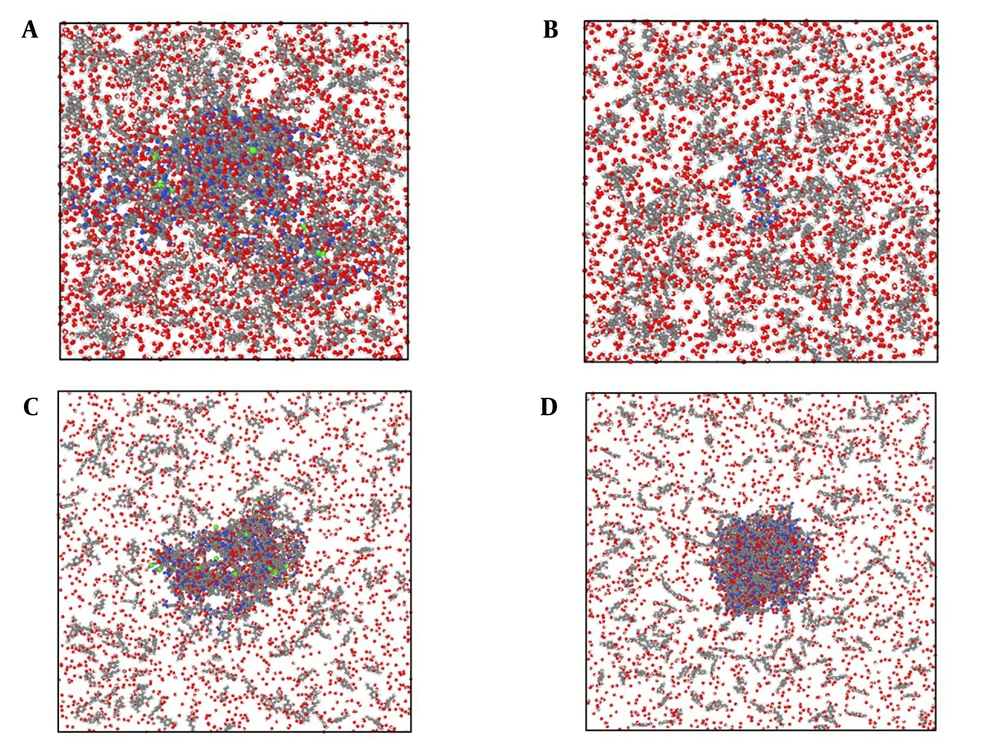

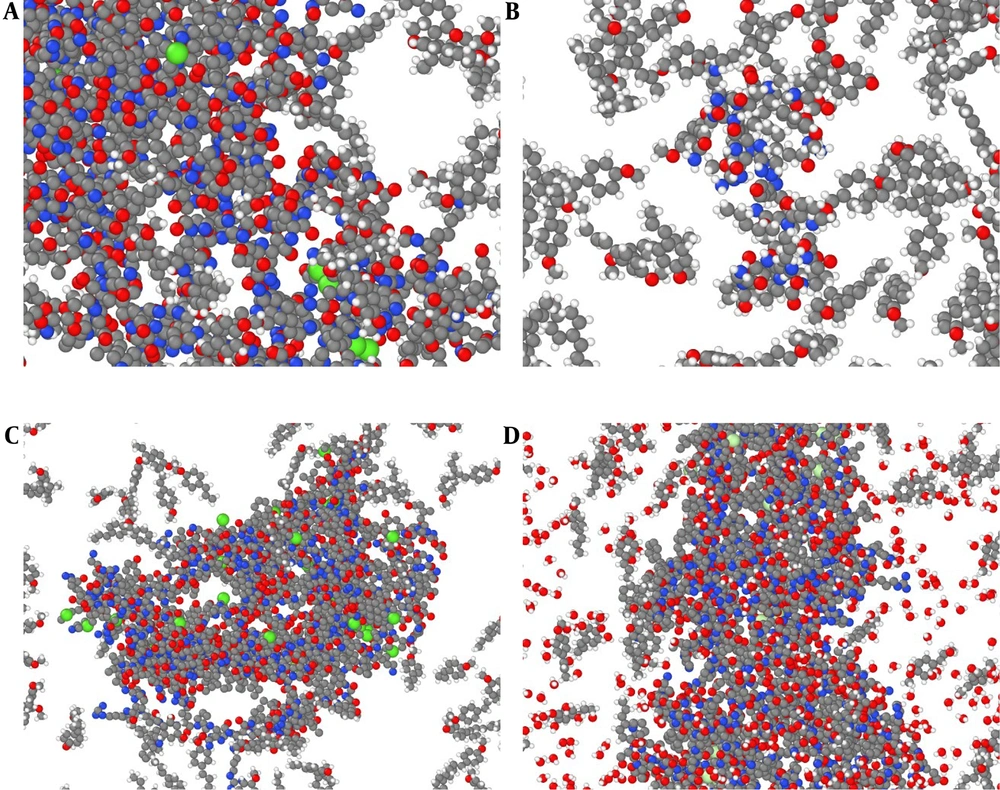

Our initial modeled systems in the current research are depicted in Figure 1. The zoomed snapshot from them is reported in Figure 2 for a better understanding of the atom-based sample arrangement. In these samples, 14,110/10,920/13,722/14,932 atoms were defined inside the computational box in the presence of the t-anethole drug and 6KS0 adiponectin/6H3E ghrelin/8DHA leptin/7X9C neuropeptide Y hormone receptors. These atomic structures were modeled using Avogadro and Packmol packages. After initial atomic designing, the Conjugate Gradient method was used to optimize the geometry in these samples. Also, more MD settings in the described two computational phases are listed in Table 1. These MD settings were implemented in the LAMMPS package to describe the atomic evolution of modeled systems (25-27). Additionally, simulations were done five times, and the average outputs of them were reported.

Atomic representation of the t-anethole drug in combination with A, adiponectin, B, ghrelin, C, leptin, and D, 7X9C neuropeptide Y hormone receptor systems in an aqueous environment from a perspective view. In these graphical outputs, C, H, N, O, P, S, and Zn atoms are represented with gray, white, blue, red, violet, green, and dark gray, respectively. These atomic samples were graphically rendered using the OVITO software (28).

| MD Details | Value/Setting |

|---|---|

| MD box size | 1000 - 4096 nm3 |

| Boundary condition | PBC (29) |

| Initial temperature | 300 K |

| Time step | 0.1 fs |

| Computational ensembles | NVT/NVE |

| Temperature damping ratio | 10 |

| Equilibrium time (initial step) | 10 ns |

| Interaction time (final step) | 10 ns |

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. MD Outputs and Discussion

2.1.1. Physical Stability of Modeled Samples and Validation Process of MD Approach

In this computational step, the equilibrium phase of various systems at 300 K (as the initial condition) is reported. For this purpose, the atomic samples' temperature was equilibrated at the target value for 10 ns using the Nose-Hoover thermostat (30, 31). The kinetic energy outputs in this section predicted that the mobility of particles in various samples decreases as simulation time progresses, as shown in Figure 3. This time evolution caused the atomic fluctuations to decrease and converge to a constant value as MD time steps passed. In actual cases, this performance indicates the structural stability of the sample under defined conditions. Numerically, this parameter value converged to 1.50, 1.00, 1.45, and 1.22 kcal/mol in the presence of adiponectin, ghrelin, leptin, and 7X9C neuropeptide Y hormone receptors, respectively (in the final time step of the equilibrium phase).

In our results, model A represents the adiponectin receptor-t-anethole drug, model B represents the ghrelin receptor-t-anethole drug, model C represents the leptin receptor-t-anethole drug, and model D represents the 7X9C neuropeptide Y receptor-t-anethole drug systems (Figure 1S and Table 1S in the Supplementry File).

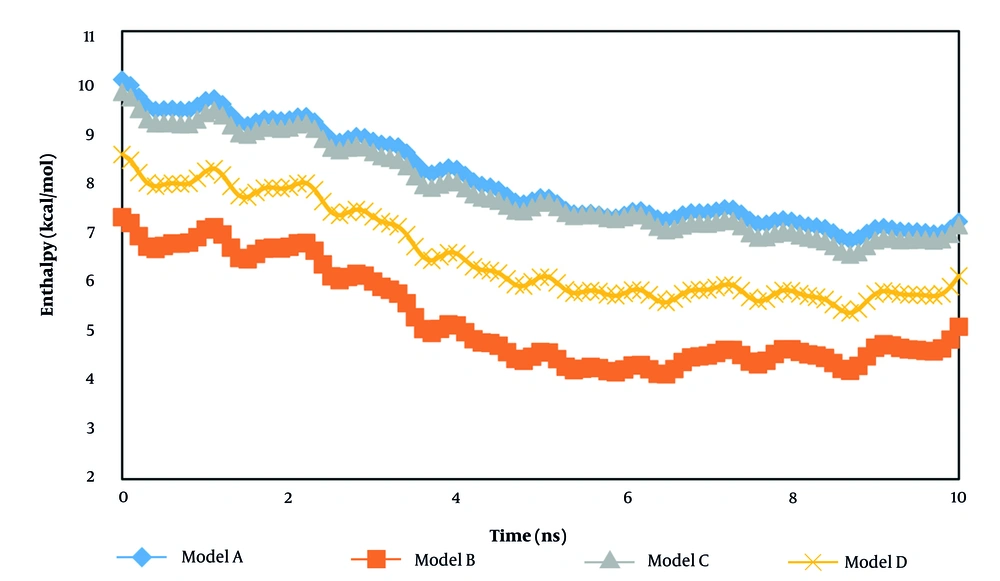

2.1.2. The Atomic Interaction Between T-Anethole Drug and Various Target Hormone Receptors

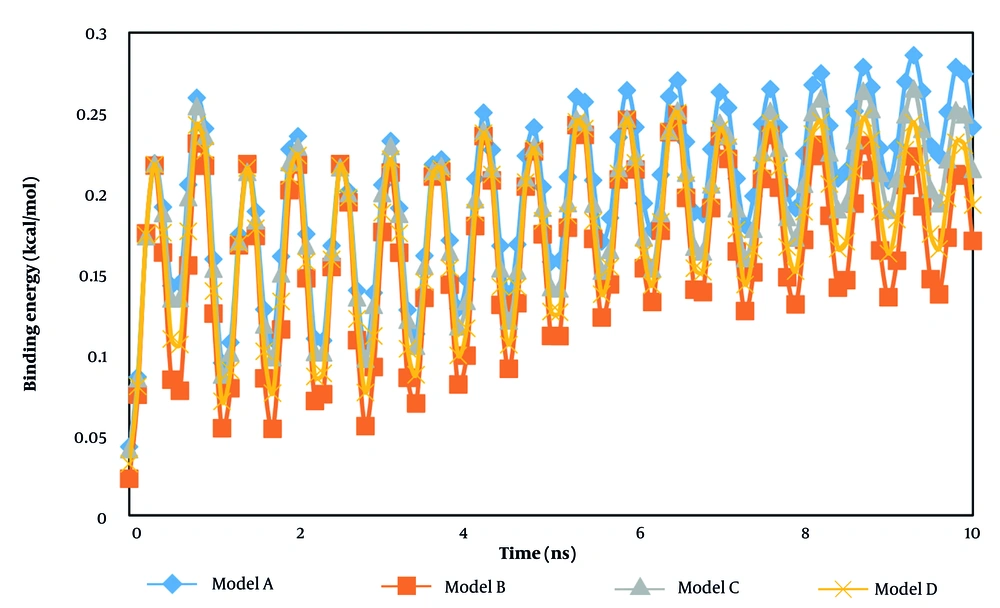

In the second step of the current research, the atomic interaction between the t-anethole drug and various hormone receptors was estimated. Our calculations for this purpose were conducted after detecting the equilibrium phase inside the computational box. Figures 4 and 5 show the enthalpy and binding energy changes as a function of simulation time. The binding energy is a calculated estimate of the free energy of the designed bio-system. In all modeled samples, the enthalpy converged to a constant value after 10 ns. This performance arises from the stability between the drug and receptor system. Numerically, the enthalpy describes the energy of an atomic system. In the context of atomic samples, enthalpy represents the amount of energy absorbed or released during a chemical reaction involving those particles. Numerically, this thermodynamic parameter reaches 7.17, 5.06, 7.10, and 6.08 kcal/mol in the presence of adiponectin, ghrelin, leptin, and 7X9C neuropeptide Y hormones, respectively.

From the numeric results, we concluded that the designed drug interacted effectively with the adiponectin sample. Thus, using the t-anethole drug in adiponectin-based treatments should yield promising outcomes in actual cases. Experimental studies show promising physical stability for t-anethole drug-hormone receptor-based systems, which is consistent with the enthalpy outputs of the current research (32-34). Additionally, the binding energy analysis can describe the stability of modeled systems. As listed in Table 2, this parameter converged to 0.24 kcal/mol in the presence of the adiponectin hormone. Previous simulation reports conducted for the t-anethole drug-hormone receptor system indicated similar behavior (35, 36). This similarity indicates that the simulation settings, such as biostructure designing and interaction defining, were done appropriately, and MD outputs can be implemented in actual cases.

| System ID | Enthalpy | Binding Energy |

|---|---|---|

| A | 7.17 ± 0.02 | 0.24 ± 0.01 |

| B | 5.06 ± 0.01 | 0.17 ± 0.02 |

| C | 7.10 ± 0.05 | 0.22 ± 0.03 |

| D | 6.08 ± 0.04 | 0.19 ± 0.03 |

a Values are expressed as kcal/mol and mean ± SD.

Among various samples, the highest binding energy was detected for the adiponectin sample compared to other structures, which is physically characterized by a strong and specific interaction typically involving extensive hydrogen bonding and hydrophobic contacts. This high binding affinity represents the stability and strength of the drug-target complex. Such drug-cell binding is also marked by a reduced dissociation rate constant, indicating that once the drug binds to its specific target, it remains bound for a prolonged time, enhancing selectivity and therapeutic efficacy. This result predicts that the t-anethole drug-adiponectin hormone system has maximum stability in clinical applications, which should be considered in drug designing procedures.

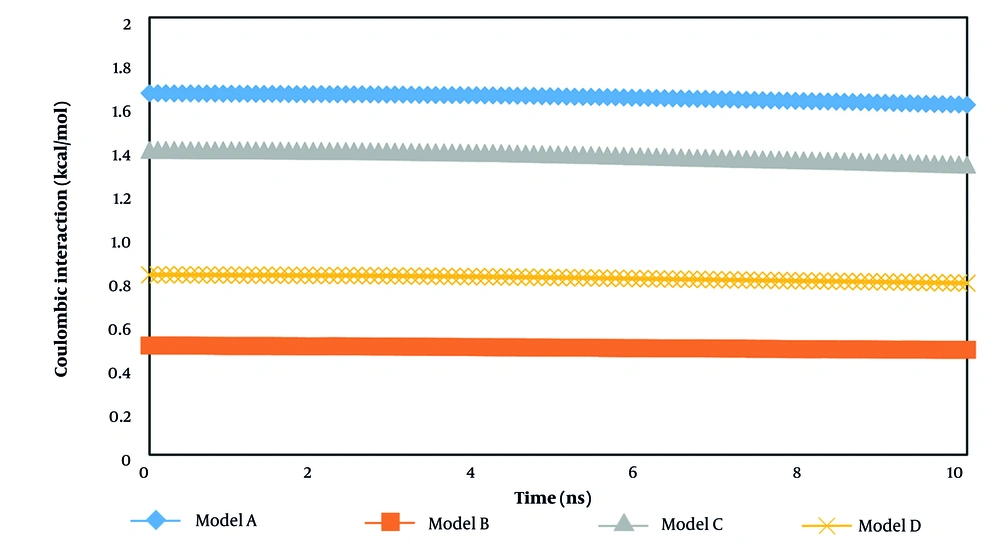

The atomic interaction and physical stability of systems can be described by calculating coulombic and van der Waals forces. Figure 6 presents the coulombic force between the drug and target receptor. The coulombic interaction refers to the electrostatic attraction or repulsion between charged particles in atomic samples. Among various samples, system A exhibits the maximum value of electrostatic interaction, causing the drug and receptor mean positions to converge in proximity to each other. This parameter value among various samples in MD changes from 4.06 to 5.40 kcal/mol. These converged ratios illustrate the effective interaction between the drug and hormones in an aqueous environment. Thus, the t-anethole drug can be regarded as an appropriate chemical sample for treatment procedures for defined hormones.

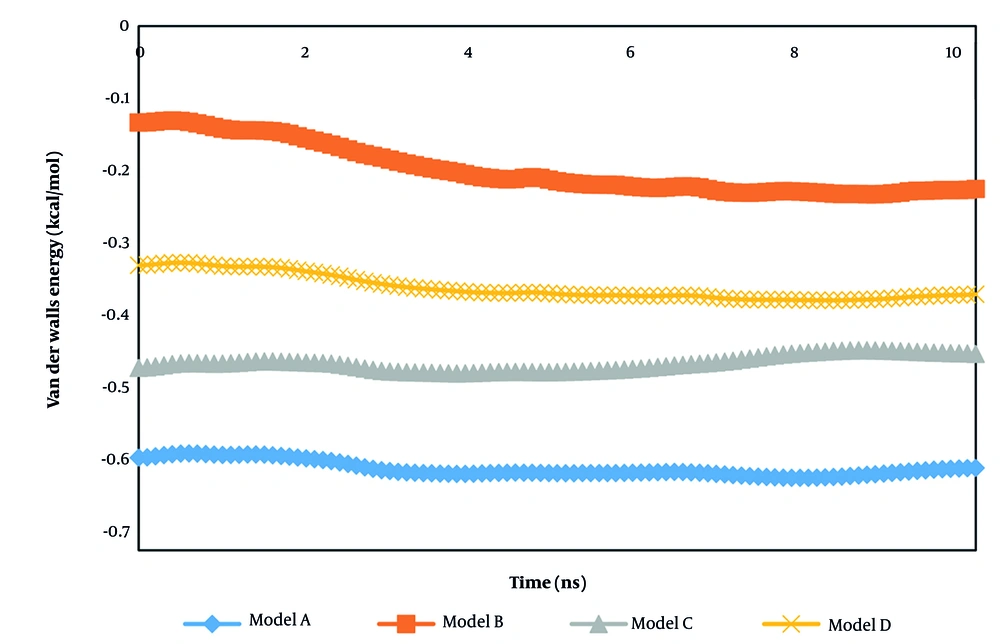

The van der Waals interaction predicted similar results to the coulombic interaction outputs. This type of interatomic force converged to a constant value after 10 ns (Table 3). Technically, these MD results predict that 10 ns is sufficient time to detect the final phase of the current biostructures, as shown in Figure 7.

| System ID | Coulombic Energy | Van der Waals Energy | Potential Energy |

|---|---|---|---|

| A | 5.40 ± 0.02 | -0.59 ± 0.02 | 1.60 ± 0.01 |

| B | 4.06 ± 0.01 | -0.22 ± 0.02 | 0.48 ± 0.01 |

| C | 5.13 ± 0.05 | -0.44 ± 0.01 | 1.32 ± 0.02 |

| D | 4.60 ± 0.03 | -0.36 ± 0.03 | 0.78 ± 0.01 |

a Values are expressed as kcal/mol and mean ± SD.

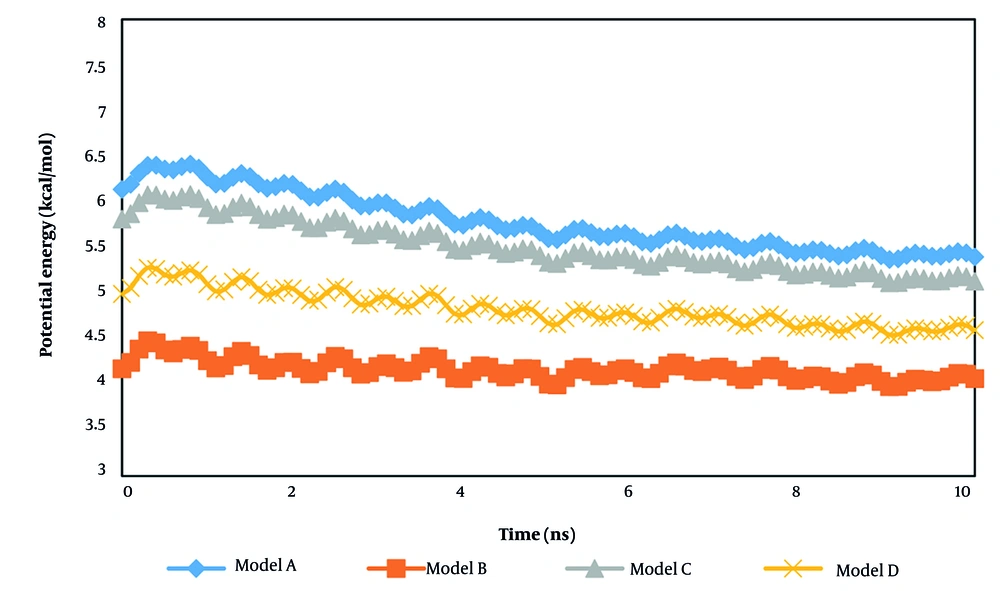

In the next step of the current research, the potential energy of the total systems equilibrated in this research is reported. In biostructures, potential energy refers to the energy stored in molecules due to their relative positions and interactions with other molecules. Understanding the potential energy landscape of biostructures is important for predicting their behavior and designing drugs that target specific molecular interactions.

As shown in Figure 8, the potential energy reached 1.60, 0.48, 1.32, and 0.78 kcal/mol in the presence of adiponectin, ghrelin, 8DHA leptin, and 7X9C neuropeptide Y receptors, respectively. This energy convergence predicts the atomic stability of the system after structure adsorption (Figure 9). This evolution arises from the attractive force between the t-anethole drug and various receptors. Furthermore, the maximum value of potential energy in system A predicts greater chemical resistance, which should be considered in actual clinical cases.

By comparing the coulombic and van der Waals interaction outputs reported in Table 3, we concluded that electrostatic interactions dominate inside the computational box due to their crucial role in determining the structure, stability, and function of bio-systems. Unlike van der Waals forces, which are short-range and significant only at close proximity, electrostatic forces act over longer distances and arise from interactions between partially charged groups, as well as correlated dipoles in hydrophobic environments where solvent screening is minimal.

Finally, the interaction energy and root mean square deviation (RMSD) parameter were calculated in the designed systems for more structural analysis. The RMSD in biostructures and the drug designing process is a quantitative measure of the average distance between corresponding atoms, usually backbone atoms, of two superimposed molecular structures after optimal alignment. This parameter value is calculated as the square root of the average of the squared distances between pairs of equivalent atoms, helping to summarize structural deviation in a single value.

This structural parameter reaches its maximum value in SAMPLE B (4.18 Å) after 10 ns, as listed in Table 4. This behavior indicates that structural evolution can occur in less time in actual clinical cases. Physically, this performance can be concluded from the interaction energy analysis of the system. The interaction inside the bio-system and this sample, as well as the aqueous environment, reached a minimum magnitude (with a negative value) in this sample (-1.07 and -0.18 kcal/mol, respectively). This behavior caused the atomic evolution intensity to increase inside this sample compared to other structures.

| System ID | Interaction Energy in Bio-system (kcal/mol) | Interaction Energy Between Aqueous Environment and Bio-system (kcal/mol) | RMSD (Å) |

|---|---|---|---|

| A | -1.58 ± 0.05 | -0.33 ± 0.02 | 3.69 ± 0.02 |

| B | -1.07 ± 0.01 | -0.18 ± 0.02 | 4.18 ± 0.04 |

| C | -1.34 ± 0.02 | -0.25 ± 0.01 | 3.92 ± 0.02 |

| D | -1.22 ± 0.03 | -0.21 ± 0.01 | 4.11 ± 0.02 |

Abbreviation: RMSD, root mean square deviation.

a Values are expressed as mean ± SD.

3. Conclusions

The MDS is a computational technique used to study the behavior and interactions of atoms and molecules over time. In the context of biomaterials, MD simulation is employed to investigate the structural, mechanical, and dynamic properties of biomolecules and materials at the atomic level. In the current research, we implemented an equilibrium MD approach to describe the atomic interaction between the t-anethole drug and various target hormone receptors (such as 6KS0 adiponectin, 6H3E ghrelin, 8DHA leptin, and 7X9C neuropeptide Y samples).

The MDS outputs show that the total energy of modeled samples converged to a constant value (from 5.06 to 6.90 kcal/mol) at 300 K. This performance predicts the physical stability of modeled structures under clinical conditions. Next, the atomic interactions between the drug and various receptors were estimated with calculations of enthalpy, binding, coulombic, van der Waals, and potential energies. Numerical outputs show that the enthalpy of the t-anethole drug-adiponectin system converged to an optimum value (7.17 kcal/mol). Physically, higher enthalpy corresponds to more stabilized interactions that resist thermal fluctuations and molecular perturbations, effectively increasing the energy required to disrupt the structure. Thus, we concluded that this atomic system can be used effectively for treatment procedures on a nanoscale.

Furthermore, the physical stability analysis of this sample shows appropriate stability for actual applications. We expect that our MD results in the current research can improve the efficiency of various treatment processes based on the t-anethole drug.