1. Background

Enhancing the permeability and absorption of drugs is a critical challenge in pharmaceutical sciences. Among the factors influencing permeability, particle size plays a key role, particularly for antibiotics whose therapeutic effectiveness depends on efficient tissue penetration (1). Smaller particles tend to exhibit higher surface area, increased solubility, and better mucosal interaction, leading to improved absorption across the intestinal barrier (2, 3). In addition to physicochemical factors, biological mechanisms such as efflux transporters also limit drug absorption. One of the most well-studied is P-glycoprotein (P-gp), a glycosylated membrane transporter encoded by multidrug resistance genes. This protein actively exports drugs from the enterocytes back into the intestinal lumen, reducing their net absorption and oral bioavailability. Well-known drugs such as carbamazepine and propranolol are affected by P-gp-mediated efflux (4). Understanding and overcoming this barrier, for example, through formulation strategies or selective inhibitors, is essential to improve oral drug delivery (4).

The oral route of administration remains the most preferred method for drug delivery due to patient convenience and compliance. However, many drugs fail to achieve adequate systemic exposure when given orally, mainly because of poor permeability, low solubility, or extensive first-pass metabolism (2, 5).

The small intestine is the main site of drug absorption and includes two primary transport pathways: Paracellular and transcellular. While lipophilic compounds typically cross via transcellular diffusion, hydrophilic molecules may depend on paracellular pathways or specific transporters (4). An example includes metformin, which is absorbed via specific transporters or paracellular pathways in nonlinear kinetics in the rat intestine (6).

The gastrointestinal mucosa poorly absorbs vancomycin (VCM) hydrochloride due to its large hydrophilic molecule. For this reason, VCM is poorly absorbed in the large intestine to treat intense Clostridium difficile when administered orally (7, 8). In systemic infections, this antibiotic should be administered intravenously due to its disability to pass through the intestinal barrier (2). Beyond its absorption limitations, the clinical landscape is further complicated by the emergence of vancomycin-resistant Enterococcus spp. (VRE). Recent epidemiological studies in Zahedan have reported a high prevalence of VRE, underscoring the urgent need for new and more effective VCM delivery strategies (9).

Nanoparticle-based drug delivery systems offer a promising approach to address poor oral absorption. Nanoparticles can increase mucosal contact time, bypass first-pass metabolism, and protect drugs from degradation in the gastrointestinal tract (10, 11). By facilitating transcytosis via M cells, nanoparticles can also enhance lymphatic uptake and systemic exposure without passing through the portal vein (10). These mechanisms can lead to improved bioavailability and more consistent plasma concentrations. Similar nano-formulation strategies have successfully improved the intestinal permeability and therapeutic effect of other poorly absorbed compounds, such as rutin, in rat models of ulcerative colitis (12). In parallel, recent reviews have highlighted the potential of nanoparticle platforms to overcome VCM’s oral bioavailability challenges (13). These mechanisms illustrate why improving intestinal permeability is a critical step in developing effective oral formulations.

To assess intestinal permeability under physiologically relevant conditions, various in vitro and ex vivo models have been developed (14). Among these, the single-pass intestinal perfusion (SPIP) technique is one of the most widely used and reliable experimental methods (15-17). The SPIP preserves intestinal membrane integrity and mimics physiological conditions while allowing measurement of the effective permeability (Peff) of orally administered drugs (18). A non-absorbable marker, such as phenol red, is often co-perfused to correct for water flux (19). Because direct measurement of human intestinal permeability is complex and ethically challenging (20), rat SPIP models have been validated as predictive tools for human intestinal absorption (21-23).

2. Objectives

Based on this knowledge, the primary objective of this research was to enhance the intestinal permeability and oral bioavailability of VCM by converting it into a nanoparticle formulation suitable for oral administration. Using the rat intestinal permeability model, this study aimed to establish a more accurate correlation for predicting human Peff, fraction absorbed (Fa), and absorption number (An). The research specifically focused on permeability and oral bioavailability (Fa), since it is not feasible to reliably predict a drug molecule’s ability to cross the intestinal barrier solely from physicochemical parameters such as pKa, molecular size, or partition coefficient (24).

3. Methods

Vancomycin was provided by Jabir ibn Hayyan Company (Tehran, Iran), and the VCM nanoparticle was synthesized based on our previous work (7). Dichloromethane, KH2PO4, NaH2PO4, and triethanolamine were received from Merck Company (Germany). Acetonitrile [high performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) grade], methanol (HPLC grade), Na2HPO4, orthophosphoric acid, NaOH, NaCl, and glacial acetic acid were all purchased from Merck (Germany). Eudragit RS-100 was obtained from Rohm Company (Germany), phenol red was purchased from Sigma Chemical Company (Germany), and double-distilled water was used throughout the entire HPLC procedure.

The SPIP approach maintains an intact blood supply, a functional intestinal barrier, and circumstances that are remarkably similar to those found in the normal physiological state. The rat and human jejunal Peff amounts are substantially associated with the passively absorbed medication; therefore, rat Peff amounts can be accurately utilized to estimate in vivo oral absorption in humans. Nanoparticles of VCM indicate a promising approach to tackle the common limits relating to the oral formulation that cannot be prescribed for systemic infection.

3.1. Single-Pass Perfusion of the Rat Jejunum

The SPIP investigations in rats were carried out utilizing the methods established in the literature (25) and approved by the ethics committee (IR.AJUMS.ABHC.REC.1402.085). Briefly, 10 male Wistar rats (220 – 280 g, 6 - 8 weeks old) were housed under a 12-hour light/dark cycle and fasted for 10 - 16 hours prior to the experiment, with free access to water. Anesthesia was induced via intraperitoneal injection of ketamine (70 mg/kg) and xylazine (4 mg/kg), and the animals were placed on a heated pad to maintain normal body temperature. A segment of the small intestine was surgically exposed, and a 10 - 12 cm portion of the jejunum was cannulated using plastic tubing. The intestinal segment was flushed with warm saline (37°C) and connected to a perfusion reservoir equipped with a 50 mL syringe driven by a syringe pump. To preserve an intact blood supply and minimize surgical trauma, the small intestine was carefully handled throughout the procedure. A blank perfusion buffer was administered for 10 minutes using a syringe pump, followed by perfusion with VCM solutions at concentrations of 200, 300, and 400 µg/ml, delivered at a flow rate of 0.2 mL/min for 80 minutes. Vancomycin nanoparticles were perfused at dosages of 200, 300, and 400 µg/mL at the same flow rate as the VCM solution. The perfusate was collected in microtubules every 10 minutes, and the segment’s length was measured. Samples were immediately frozen at -20°C until analysis. All animal research adhered to the Canadian Council on Animal Care’s "Guide to the care and use of experimental animals" (22).

3.2. The Compound of the Perfusion Solution

The perfusion buffer compound was 1.44 g of Na2HPO4, 0.24 g of KH2PO4, 0.2 g of KCl, and 8 g of NaCl per liter of solution. The pH of the obtained buffer was adjusted to 7.2. In each examination, 0.7 mM of phenol red was added to the solution as a non-absorbable indicator (23). In SPIP investigations, intake perfused nanoparticle concentrations (Cin) were 200, 300, and 400 µg/mL. Preliminary testing revealed that there was no appreciable adsorption of the medication on the tubing and syringe.

3.3. Stability Tests

The stability of the nanoparticles was assessed by incubating them in both the perfusion solution and the intestinal perfusate for two hours at 37°C. Samples were collected at 0-, 1-, and 2-hours post-perfusion and analyzed using HPLC. The blank perfusate was prepared by passing the blank perfusion buffer through an isolated segment of the intestine in situ at a flow rate of 0.2 mL/min. No signs of drug degradation in the nanoparticle formulation were observed during the incubation period.

3.4. High Performance Liquid Chromatography Analytical Method

All samples were analyzed using reverse-phase HPLC on a Shimpak VP-ODS, C18 mm 250, 4.6 column. To make 200 mL of mobile phase, combine 1 mL of glacial acetic acid with 139 mL of distilled water, then add 60 mL of pure methanol to it. The pH of the solution is typically around 3, which is raised to 5.5 by adding triethanolamine. The mobile phase was filtered through a sintered glass filter and degassed in a sonicator under a vacuum before being pumped in an isocratic mode in all cases (23). The retention period was 4.98 minutes at a flow rate of 1 mL/min and an injection volume of 20 µL. The wavelength of 254 nm was used to determine medication concentration.

4. Results

4.1. Assessment of Effective Permeability of Drugs by the Single-Pass Intestinal Perfusion Method

Any in situ intestinal perfusion method must characterize the amount of solution volume changes in the gut lumen during the investigation. For this purpose, phenol red (0.7 mM) was added to the drug solution in each experiment. Phenol red was employed as a non-absorbable indicator to determine if the lumen gained or lost water. This factor did not have an effect on medication absorption in this research. The consistent water flux and permeability coefficient in each perfusion for the drug carried passively and via a carrier-mediated mechanism revealed that the intestinal barrier function was maintained throughout the procedure. Tables 1 and 2 show the determined Peff, Fa, and An values for nanoparticles and drug solution at various doses using the SPIP method.

Abbreviation: Peff, effective permeability.

a Receiving vancomycin solution.

b Receiving vancomycin nanoparticles.

| Groups | 200 (µg/mL) | 300 (µg/mL) | 400 (µg/mL) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Control rats (n = 5) | 0.297 | 0.431 | 0.300 |

| 0.605 | 0.500 | 0.426 | |

| 0.202 | 0.652 | 0.146 | |

| 0.359 | 0.535 | 0.328 | |

| 0.315 | 0.504 | 0.206 | |

| Test rats (n = 5) | 0.600 | 0.863 | 0.187 |

| 0.437 | 0.918 | 0.690 | |

| 0.578 | 0.609 | 0.521 | |

| 0.515 | 0.682 | 0.629 | |

| 0.798 | 0.636 | 0.240 |

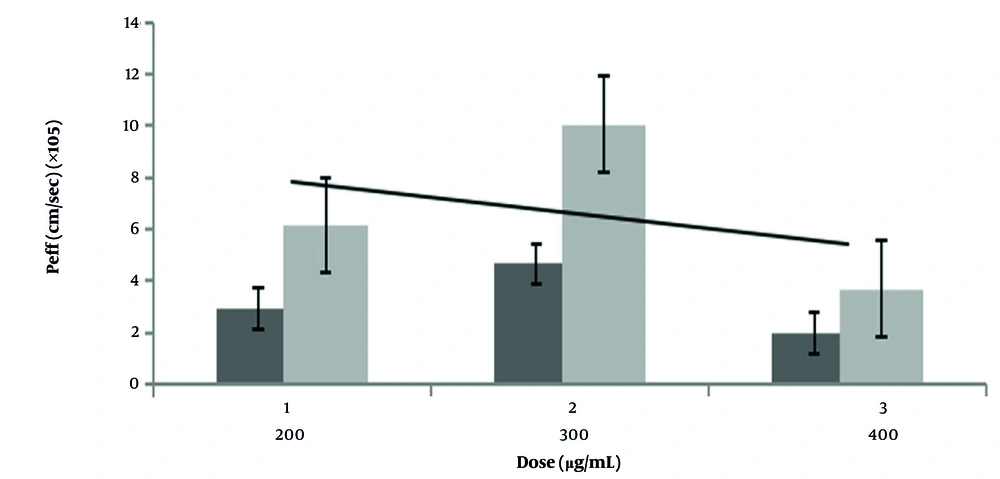

Results indicate that the mean Peff of VCM in nanoparticle form with a 1 cm per sec rate of flow had significant differences from VCM solution in inter solution concentration of 300 µg/mL, while it did not show significant differences in concentration of 400 µg/mL. Also, data on the mean Peff of VCM at a concentration of 200 µg/mL represented that although the P-value of this group was higher than 0.05 (0.0516), while it is close to the P-value of 0.05, which means approximately a significant Peff value between VCM in nanoparticle form and VCM solution.

A strong correlation was observed between rat permeability data and the fraction of the oral dose absorbed in humans, following a Chapman-type equation model (Equation 1):

The Fa is calculated from the equation. The Fa (prep) is an orally absorbable fraction, and Peff is the effective permeability of the rat intestine. The tres value is the average speed of a drug through the small intestine, which is considered to be 3 hours. The R is the radius of the human small intestine, which is 1.75 cm, and f is the correction factor that is equal to 2.8 (26). Statistical tests represented an increase in Fa of VCM nanoparticles (P < 0.05). The relationship between the oral Fa, the drug absorption rate constant (Ka), and the drug transfer rate constant (reflecting residence time in the small intestine) suggests that increases in Fa for nanoparticle formulations result from enhanced absorption or prolonged intestinal residence. For drugs like VCM — and more broadly, those classified under Biopharmaceutics Classification System (BCS) classes I and III — Fa is influenced by both the absorption rate constant and the rate at which the drug transits through the small intestine (27).

The An is the exposure time of the drug to the absorption time of the drug in the small intestine. The An can be calculated using the Fa; An can be calculated using the Equation 2 (28):

The amount of an is shown in Table 3. Statistical tests demonstrated a significant difference between the test and control groups (P < 0.05).

| Groups | 200 (µg/mL) | 300 (µg/mL) | 400 (µg/mL) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Five control rats | 0.212 | 0.379 | 0.214 |

| 0.766 | 0.501 | 0.370 | |

| 0.141 | 0.935 | 0.085 | |

| 0.280 | 0.575 | 0.244 | |

| 0.230 | 0.507 | 0.130 | |

| Five test rats | 0.750 | 3.142 | 0.115 |

| 0.389 | 5.610 | 1.111 | |

| 0.686 | 0.778 | 0.543 | |

| 0.531 | 1.072 | 0.848 | |

| 1.977 | 0.875 | 0.158 |

4.2. Data Analysis Method

The Peff was calculated based on the steady-state concentrations of drug-containing nanoparticles in the collected perfusate. Steady state was considered to be achieved when the concentration of phenol red stabilized, which occurred approximately 40 minutes after the start of perfusion. This was confirmed by plotting the ratio of outlet to inlet concentrations over time to monitor water transport. Correctional testing showed a significant difference between the test and control groups. The intestinal net water flux (NWF, μL/h/cm) was calculated according to the Equation 3:

In which [Ph.red(in)] and [Ph.red(out)] are the inlet and outlet concentrations of phenol red, that is, a non-absorbable material. Also, l is the length of the intestine segment. A negative net water flux represents the loss of fluid from the lumen to the serosal side, and a positive net water flux demonstrates the transudation of fluid into the segment. The Q is the flow rate (0.2 mL/min) (29). After measuring drug concentrations in the outlet solution, the concentration was corrected in proportion to the phenol red concentration changes by the following formula (Equation 4):

CPRout and CPRin represent the concentrations of phenol red solution at the outlet and inlet, respectively. Cout denotes the drug concentration at the outlet, while Ccor refers to the corrected drug concentration in the outlet solution. Because phenol red is not absorbed in the intestine, variations in its concentration indicate the relative rate of water movement between the inlet and outlet. The corrected concentration, Ccor, reflects the drug concentration in the outlet solution after adjusting for water transfer. The effective permeability was determined using the parallel-tube model, as shown in Equation 5 (21, 25):

In this model, Cin and Cout represent the inlet and outlet concentrations of the drug or nanoparticles, respectively, corrected using the phenol red concentrations in the corresponding inlet and outlet samples. The Q denotes the flow rate (0.2 mL/min), r is the intestinal radius in rats (0.18 cm) (26), and l is the length of the perfused intestinal segment. It has been demonstrated that in humans, at an inlet flow rate (Qin) of 2 mL/min, Peff is primarily membrane-controlled. In the rat model, however, a Qin of 0.2 mL/min is used, given that the intestinal radius in rats is approximately ten times smaller than that in humans (26). In this study, the rats were divided into six groups, five rats each: Three test groups receiving VCM nanoparticles at concentrations of 200, 300, and 400 µg/mL, and three control groups receiving VCM conventional particles at concentrations of 200, 300, and 400 µg/mL. The relationship between Peff in the human and rat intestines is as follows. Human Peff can be calculated from Equation 6 (Figure 1) (23).

5. Discussion

According to Yuasa et al. (as cited by Saphier et al.), anesthesia impairs intestinal absorption in rats. In fact, both surgical procedures and anesthesia can reduce blood circulation and intestinal motility, thereby diminishing the efficiency of both passive and active transport mechanisms. Anesthetic drugs may also directly influence the cell membranes (30). Furthermore, rat intestinal permeability varies with age. Although age-related differences in intestinal permeability may exist in very young or old rats, no significant effect of age on jejunal permeability has been reported in rats between 5 and 30 weeks of age (31).

The physicochemical properties of VCM nanoparticles are key determinants of the improved intestinal permeability. The VCM nanoparticles, which were prepared from our previous work, had a mean particle size of approximately 430 nm, zeta potential +25.7 mV, loading efficiency around 89%, and smooth, spherical morphology with uniform distribution and minimal aggregation (7). Particles within the sub-micron range possess a high specific surface area, which enhances drug dissolution at the epithelial interface and promotes diffusion through the unstirred water layer. Their positive surface charge facilitates electrostatic interactions with the negatively charged intestinal mucosa, improving adhesion and residence time, which increases the likelihood of transcellular or paracellular uptake. The smooth, non-aggregated morphology further enhances mucus penetration compared with rough or irregular particles, which are more readily trapped in the mucin network. Previous works showed that nanoparticles with such properties could effectively pass through the intestine (32-34).

In the present study, the calculated Peff values for the nanoparticles ranged from 3.68 × 10-5 to 10.06 × 10-5 cm/s and showed a great correlation with human Peff data for passively absorbed drugs, supporting the reliability of our approach. This data is compatible with the previous finding that there is a high correlation between rat Peff values and humans by using the SPIP method to precisely predict human intestinal permeability (18, 23). The Peff assessment of the nanoparticle form compared to the conventional VCM form revealed greater permeability of nanoparticles 2.16, 1.43, and 2.66 times than the conventional form at 200, 300, and 400 µg/mL, respectively. This is a non-linear relation in permeability among different VCM concentrations. This data is compatible with previous work that found the intestinal permeability of VCM is not concentration-dependent (35). Additionally, as VCM has hydrophobic properties, this could lead to the aggregation of nanoparticles at higher doses and influence their absorption (36).

According to the study of Salphati et al. in the ileum (37) and Fagerholm et al. (26) in the jejunal segment, the equation was calculated. They found that the slopes for the same correlation between the two segments were 6.2 and 3.6, respectively. The differences in category and effective absorptive area may indicate lower permeability values in the rat model. Additionally, variations in intestinal barrier activity during surgery could be the primary reason for conflicting conclusions regarding nanoparticle intestinal permeability in written reports. The comparison of rat and human Peff values for nanoparticles showed that in rats, it is 3.68 × 10-5 cm/sec, whereas human Peff values are at least 1.29 × 10-4 cm/sec. Furthermore, the anticipated and actual human Fa% have a linear correlation with Peff. Based on our findings, we propose that the in situ intestinal perfusion method in rats can serve as a reliable model for predicting the extent of human gastrointestinal absorption following oral drug administration.

Although the stability of VCM nanoparticles was evaluated for a duration of 2 hours, which corresponds to the typical contact period of the perfusate with the intestinal segment during SPIP experiments (23), this perfusion duration time does not fully represent the longer gastrointestinal transit time that happens for orally administered drugs. Therefore, assessing the VCM nanoparticles with gastrointestinal transit time around 4 - 6 hours for the small intestine with varying pH conditions, bile salts, digestive enzymes, and mucus interactions over these longer durations could provide a more comprehensive understanding of nanoparticle behaviour during oral transit and absorption of this formulation (38, 39). Also, to enhance the reliability of our findings, it is necessary to include a broader range of drugs from all four BCS classes, encompassing a variety of solubility and permeability profiles (40), particularly drugs with low permeability, which should be studied. The recommended dose is 300 µg/mL, as greater doses may promote carrier transport saturation and decreased permeability.

5.1. Conclusions

Considering the results, using the SPIP method in rats to measure intestinal permeability had a high correlation with human data. Also, using VCM in its nanoparticle form showed better intestinal permeability and oral absorbable fraction than the routine form of it. While these findings provide valuable insights into the mechanisms underlying improved absorption, they should be interpreted within the limitations of an animal model. The present data suggest that such nanoparticles hold promise as a potential oral delivery system for VCM; however, further pharmacokinetic studies, long-term stability evaluations, and clinical trials are required to confirm their efficacy and safety in humans.