1. Background

The pharmacological landscape of calcineurin inhibitors (CNIs), encompassing FDA-approved drugs such as cyclosporine A (CsA), tacrolimus (TAC) (1), and voclosporin (2), has been extensively documented in numerous reviews, highlighting their pivotal role in managing organ transplantation and autoimmune disorders. However, despite their therapeutic efficacy, CNIs are plagued by a spectrum of adverse drug reactions and pharmacokinetic (PK) constraints (3-5). Certain phytochemicals, renowned for their antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, and diverse biological effects, have shown promise in modulating calcineurin activity; however, the precise structure-based mechanism of action remains incompletely understood. While several studies have demonstrated their potential in this regard, further research is needed to elucidate their mechanisms fully (6, 7). Molecular docking (MD) emerges as a pivotal virtual screening tool for drug discovery (8). Notably, research has demonstrated that flavonoids, such as quercetin, bind to calcineurin in a manner similar to CsA and TAC (9). Kaempferol (KF), a flavonol renowned for its diverse biological activities, including hypoglycemic and nephroprotective effects (10), holds promise as an inhibitor of calcineurin.

2. Objectives

This study aims to elucidate the pathophysiological mechanisms of oxidative stress and calcineurin B1 (CnB1) in TAC-induced hyperglycemia while probing the protective potential of KF.

3. Methods

3.1. Molecular Docking Screening

3.1.1. Protein Structures and Preparation

The crystallographic structures of calcineurin [calcineurin A (CnA), CnB1] and its related immunophilin chains [cyclophilin A, FKBP12; Protein Data Bank (PDB) IDs: 4OR9; 1MF8, 4IPZ, 1FKJ] were retrieved from the PDB in 3D PDB format. These targets were prepared using the CHARMM-GUI PDB Reader and Manipulator and the Maestro software suite. The preparation process included selecting the appropriate model at pH 7.4, modeling missing residues, optimizing hydrogen bonds, and generating the final version of the PDB files. Energy minimization of the protein structures was performed using the preparation wizard from Maestro-GUI and the YASARA Server with default parameters and force field protocol to relieve local steric clashes and optimize geometry.

3.1.2. Ligand Preparation

Flavonoid ligands — KF, quercetin, and isoquercetin — along with the reference compounds FK506 (TAC) and CsA were obtained from PubChem in SDF format. Ligand preparation was carried out at pH 7.4 with energy minimization using the OPLS and MMFF94 force fields and the Steepest Descent algorithm with a total of 200 steps. This process was executed by the Maestro LigPrep wizard.

3.1.3. Docking Setup

Structure-based blind docking, which defines the entire protein surface as the search space, was performed using the AutoDock-based SeamDock web server. This was followed by active (cognate) binding site docking using the Glide XP tool from Maestro-GUI to ensure the reliability of the results and to provide more detailed insights into ligand-target interaction profiles. The docking parameters were set as follows: Grid spacing: 1.0 Å; Exhaustiveness: 8; Energy range: 3 kcal/mol; Number of binding modes saved: 8. Binding poses were ranked according to predicted binding affinity (ΔG, kcal/mol).

3.2. Absorption, Distribution, Metabolism, Excretion, and Toxicity Profile

In silico prediction of molecules' physicochemical and PK properties, including absorption, distribution, metabolism, excretion, and toxicity (ADMET) parameters, was performed using the ADMETlab 3.0 platform (11).

3.3. In vivo Study Design

This experiment was conducted as a 30-day in vivo model using twenty-four rats, which were randomly and equally allocated into three groups (n = 8 per group), housed four per cage. Group 1 received intraperitoneal injections of TAC (0.6 mg/kg); group 2 was administered both KF (10 mg/kg, peroral) and TAC (0.6 mg/kg, intraperitoneal); and group 3 (control) received only the vehicles [0.5 mL of 0.5% carboxymethyl cellulose (CMC) aqueous suspension, peroral] and (0.1 mL of propylene glycol, intraperitoneal). The concept of dose extrapolation between species was applied, with the TAC animal equivalent dose formulated based on a human maintenance dose (0.1 mg/kg/day) (12).

3.4. Animals

Twenty-four male albino Wistar rats, aged eight weeks and weighing approximately 180 - 230 g, were utilized for this study after obtaining ethical approval (No. 349-18) from the Biomedical Ethics Unit, Faculty of Medicine, King Abdulaziz University (KAU). The welfare of laboratory animals was maintained in accordance with national and World Small Animal Veterinary Association (WSAVA) guidelines throughout the experimental period, under optimal laboratory conditions (a 12-hour light/dark cycle, 45 - 55% relative humidity, and a temperature range of 22 - 25°C). All groups were provided ad libitum access to a standard rodent chow diet and water.

3.5. Chemicals and Equipment

The KF powder (CAS No. 520-18-3, Natural Field); propylene glycol liquid; sodium CMC powder (Sigma Aldrich); TAC powder (CAS No. 109581-93-3, HuiChem); distilled water; absorbance microplate reader (BioTek, ELx808); microplate washer (BioTek, ELx50); tissue homogenizer (Kinematica, Polytron PT10/35); laboratory incubator (SANYO, MIR-162); single/multi-channel pipettes (Globe Scientific, Diamond Pipettors); refrigerated centrifuge (SIGMA, 2-16KL).

3.6. Drugs Preparation

The KF powder was suspended in 0.5% w/v aqueous CMC, while TAC powder was dissolved in propylene glycol solvent to prepare five-day stock solutions, which were stored at 2 - 8°C in light-protected bottles. Daily doses were quantified based on the rats' weight.

3.7. Preparation of Serum and Pancreas Tissue Homogenate

Anesthesia was induced via intraperitoneal injection of a ketamine (90 mg/kg) and xylazine (10 mg/kg) combination. Blood samples were collected under anesthesia: Four milliliter from the retro-orbital sinus on day 15, and 10 mL from the aorta on day 30. At the end of the experiment, animals were humanely euthanized under deep anesthesia by exsanguination via the aorta, in accordance with ethical guidelines for animal research. The blood tubes were allowed to clot at room temperature for 15 minutes, followed by centrifugation at 4,000 × g for 10 minutes to obtain separated serum, which was stored at -80°C. Additionally, upon euthanasia of the rats by aortic exsanguination on day 30, approximately 0.1 g samples of pancreatic tissue were isolated and promptly frozen in dry ice, then stored at -80°C. A cold solution of phosphate-buffered saline (1%, 10× mL/g) was added to each sample collection tube before mechanical homogenization for five seconds. On the day of analysis, pancreas homogenates were centrifuged for 30 minutes at 4,000 × g (4°C) to separate the supernatant.

3.8. Serum Tacrolimus, Glucose, and Insulin Levels

On days 15 and 30, serum levels of TAC (trough) and glucose (random) were measured using competitive enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) techniques (MBS288390/MBS7233226, MyBioSource), while insulin was measured using a sandwich ELISA kit (ERINS, ThermoFisher) following the manufacturer's instructions. Optical density (OD) readings were obtained at a wavelength of 450 nm using a spectrophotometer, and appropriate calibration curves were utilized for data interpretation.

3.9. Pancreas P-glycoprotein, Glutathione, Superoxide Dismutase, Malondialdehyde, and Calcineurin B1 Levels

At day 30, the concentrations of selected biomarkers: P-glycoprotein (P-gp), superoxide dismutase (SOD), glutathione (GSH), malondialdehyde (MDA), and CnB1 were measured in pancreatic tissue homogenate using sandwich/competitive ELISA kits (SL1411Ra/SL1410Ra/SL0664Ra, SunLong Biotech; MBS738685/MBS761746, MyBioSource), according to the manufacturer's instructions. Sample OD readings were obtained at 450 nm, and biomarker concentrations were determined by interpolation from the calibration curves.

3.10. Total Protein Quantitation

The total protein content in each pancreas sample was quantified using a colorimetric bicinchoninic acid assay (23227, ThermoFisher) to ensure data standardization. The OD (absorbance) readings were obtained at 562 nm, with a detection limit of 5 µg/mL, as per the assay manual.

3.11. Assay Validation

All ELISA and colorimetric assays were performed in duplicate, and intra-assay as well as inter-assay variability were maintained within acceptable limits (< 10%). Calibration curves for each analyte demonstrated linearity across the tested concentration ranges (R2 > 0.99), and quality control samples were included to verify accuracy and reproducibility. Negative and blank controls were run with each assay batch to exclude nonspecific binding or background interference, ensuring the reliability of the reported measurements.

3.12. Statistical Analysis

A significance level of P ≤ 0.05 was considered to reject the null hypothesis. Data were presented as means ± standard deviation (SD) using GraphPad Prism 8.0. Two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) statistical test was performed, followed by appropriate post-hoc analyses (Games-Howell or Tukey-HSD) to identify differences among the compared groups.

4. Results

4.1. Molecular Docking Findings

The binding affinities of TAC (FK506), CsA, and selected flavonoids to calcineurin and related subunits are summarized in Table 1. The TAC exhibited the strongest binding affinity toward the calcineurin complex with docking energies of -10.1 and -8.4 kcal/mol, confirming its potent inhibitory activity. The KF and other flavonoids demonstrated moderate affinity toward calcineurin, and among them, Isoquercetin showed marked subtype selectivity toward cyclophilin A. According to detailed analyses from SeamDock docking, KF, as well as other flavonoids, exhibited diverse interaction patterns with calcineurin target proteins, including π-π interactions, hydrophobic contacts, and hydrogen bonds.

| Ligand Poses | Target Binding Site (kcal/mol) | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Calcineurin Complex a | CnA | CnB1 | Cyclophilin A | FKBP12 | |||||

| 4OR9 | 1MF8 | 4OR9 | 1MF8 | 4OR9 | 1MF8 | 1MF8 | 4IPZ | 1FKJ | |

| TAC (FK506) | -10.1/-4.11 | -8.4 |/-7.58 | -1.44 | -2.08 | -1.96 | -2.09 | -6.15 | -6.31 | -11.09 |

| Cyclosporin A | -2.9/-3.80 | -2.33/-4.89 | -1.98 | -1.58 | -0.62 | 0.54 b | -3.63 | -3.81 | -0.82 |

| KF | -6.8/-4.95 | -7.2/-7.05 | -3.16 | -4.30 | -1.97 | -0.61 | -5.52 | -5.61 | -5.73 |

| Quercetin | -8.2 |/-5.83 | -7.0 |/-8.39 | -3.44 | -4.78 | -3.97 | -2.28 | -6.17 | -7.89 | -5.91 |

| Iso quercetin | -6.3 |/-6.46 | -6.2 |/-10.96 | -4.14 | -6.62 | -4.56 | -2.49 | -7.98 | -7.84 | -7.42 |

| Docking tool | SeamDock/Glide | Glide | |||||||

Abbreviations: CnA, calcineurin A; CnB1, calcineurin B1; TAC, tacrolimus; KF, kaempferol.

a Complex: CnAβ-CnB1 heterodimer (4OR9); CnAα-CnB1-Cyclophilin A (1MF8).

b In valid results due to high molecular weight, and a large number of rotatable bonds.

4.2. Absorption, Distribution, Metabolism, Excretion, and Toxicity Endpoints

The KF has shown moderate lipophilicity but poor intestinal permeability, which limits its oral absorption despite acceptable drug-likeness scores (Table 2). It is highly bound to plasma proteins (~98%), has a small volume of distribution (Vd), poor ability to cross the blood-brain barrier, and strongly inhibits CYP3A4, suggesting a risk for drug–drug interactions. While nephrotoxicity and neurotoxicity are minimal, there is a moderate risk of hepatotoxicity, genotoxicity, and transporter/endocrine interactions, requiring careful pharmacologic dosing. Quercetin has broadly comparable predicted ADMET profiles to KF, including intestinal absorption, CYP interactions, protein binding, transporter effects, and toxicity risks, but is slightly more polar and water-soluble. On the other hand, Isoquercetin, a glycosylated flavonoid, is larger, more polar, and more flexible. The glycosylation (sugar moiety) significantly alters its PK behavior compared to aglycone flavonoids: It reduces lipophilicity, decreases intestinal absorption, lowers plasma protein binding, and increases tissue distribution and half-life. It exhibits moderate CYP3A4 inhibition, minimal effects on other CYPs, and slightly higher risks for liver injury and skin sensitization.

| Parameters | CsA | TAC | KF | Quercetin | Isoquercetin |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Molecular weight (Da) | 1201.8 | 803.5 | 286 | 302 | 464.1 |

| Log P (octanol/water) | 4.73 | 3.73 | 1.97 | 1.45 | 0.697 |

| Caco-2 prem. (log cm/s) | -5.08 | -5.30 | -5.97 | -6.18 | -6.27 |

| Plasma protein binding (%) | 66.2 | 92.1 | 98 | 98.7 | 84.4 |

| Vdss (L/kg) | 4 b | 8.5 b | 0.15 | 1.36 | 0.82 |

| P-gp | |||||

| Substrate | +++ | + | -- | -- | --- |

| Inhibition | +++ | +++ | -- | -- | --- |

| CYP3A4 | |||||

| Substrate | +++ | +++ | -- | -- | --- |

| Inhibition | +++ | --- | +++ | +++ | ++ |

| CYP2D6 | |||||

| Substrate | --- | --- | +++ | +++ | -- |

| Inhibition | --- | --- | - | - | -- |

| CYP2C19 | |||||

| Substrate | +++ | --- | --- | --- | --- |

| Inhibition | --- | --- | --- | --- | --- |

| CYP1A2 | |||||

| Substrate | --- | --- | -- | -- | --- |

| Inhibition | ---- | --- | +++ | +++ | -- |

Abbreviations: CsA, cyclosporine A; TAC, tacrolimus; KF, kaempferol; Vd, volume of distribution; P-gp, P-glycoprotein.

a For the classification endpoints, the prediction probability values are transformed into six symbols: (---), 0 - 0.1; (--), 0.1 - 0.3 ; (-), 0.3 - 0.5 ; (+), 0.5 - 0.7 ; (++), 0.7 - 0.9 ; and (+++), 0.9 - 1.0 .

b Prediction values are underestimated for CsA and TAC. These values provided are the average of reported values.

Most CsA predictions align with its known ADMET characteristics: It is highly lipophilic, has poor oral absorption due to P-gp efflux, moderate distribution, CYP3A4-mediated metabolism, and marked organ-specific toxicity (hepatic, renal, hematologic). The TAC, compared to CsA, is slightly smaller, less lipophilic, and more polar, with comparable intestinal permeability, higher plasma protein binding, and larger Vd. It does not inhibit CYP3A4 and is a weak P-gp substrate, unlike CsA. Both share similar organ-specific toxicity risks, but TAC may have slightly more favorable oral absorption and tissue distribution.

4.3. Kaempferol Impact on Tacrolimus Level

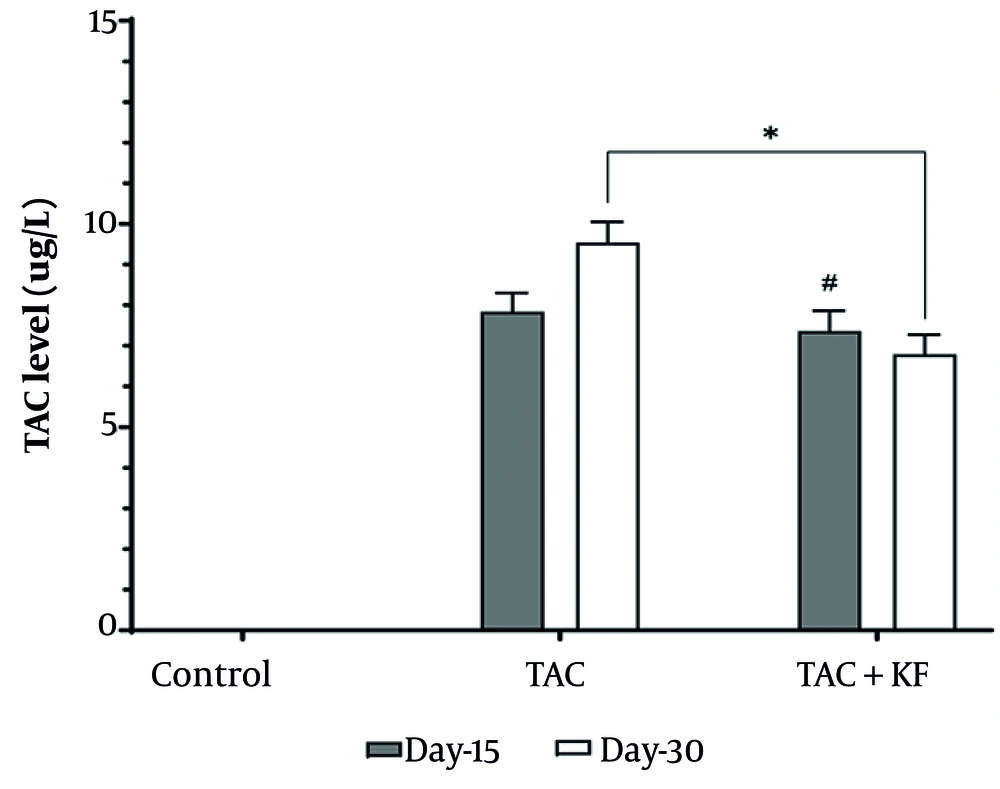

Continuous co-administration of KF for 15 days affected TAC levels in serum, as shown in Figure 1, but after 30 days, it led to a significant reduction in TAC levels.

4.4. Serum Glucose and Insulin Levels

The influence of TAC and KF on hyperglycemia biomarkers in serum, presented in Tables 3, and 4, reveals notable impacts of TAC and TAC combined with KF on serum biomarkers associated with hyperglycemia. Administration of TAC alone led to a significant (P < 0.005) increase in glucose levels by 128% and 150% at days 15 and 30, respectively, accompanied by a decrease in insulin levels by 81% and 85% at the corresponding time points. The addition of KF for 30 days resulted in a significant reduction in TAC trough levels (P < 0.005; 29%). Moreover, compared to TAC alone, the combination of KF with TAC significantly (P < 0.005) increased insulin levels by 143% and 350% at days 15 and 30, respectively, and elevated glucose levels by 35% and 50% at the same time points.

Abbreviations: TAC, tacrolimus; KF, kaempferol; NA, not applicable.

a Values are expressed as mean ± standard deviation (SD).

b Significant difference compared to the TAC group (P < 0.05).

c Significant difference compared to the control group (P < 0.05).

Abbreviations: TAC, tacrolimus; KF, kaempferol; NA, not applicable.

a Values are expressed as percentage.

b Decrease compared to the reference group.

c Significant difference compared to TAC group (P < 0.05).

d Significant difference compared to control group (P < 0.05).

e Increase compared to the reference group.

4.5. Impact of Tacrolimus and Kaempferol on Pancreas Tissue Homogenate Biomarkers

The impact of TAC and KF on pancreas tissue homogenate biomarkers is shown in Tables 5. and 6. These data demonstrate that 30 days of TAC injection resulted in a non-statistically significant decrease in P-gp, GSH, and SOD concentrations in the pancreatic tissue homogenate. Additionally, TAC administration resulted in a significant increase in MDA levels (P < 0.001, 1113%), accompanied by a decline in CnB1 concentration (P < 0.005, 98.4%). Co-administration of KF raised the pancreatic levels of P-gp (P < 0.05; 93.2%) and CnB1 (P < 0.01; 4008%), with a notable improvement in GSH levels (P > 0.05; 128%). Furthermore, the MDA level decreased significantly (P < 0.001, 62%).

Abbreviations: TAC, tacrolimus; KF, kaempferol; P-gp, P-glycoprotein; GSH, glutathione; SOD, superoxide dismutase; MDA, malondialdehyde; CnB1, calcineurin B1.

a Values are expressed as mean ± standard deviation (SD).

b Significant difference compared to the TAC group (P < 0.05).

c Significant difference compared to the control group (P < 0.05).

Abbreviations: TAC, tacrolimus; KF, kaempferol; P-gp, P-glycoprotein; GSH, glutathione; SOD, superoxide dismutase; MDA, malondialdehyde; CnB1, calcineurin B1.

a Values are expressed as percentage.

b Decrease compared to the reference group.

c Increase compared to the reference group.

d Significant difference compared to TAC group (P < 0.05).

e Significant difference compared to control group (P < 0.05).

5. Discussion

The MD results provide compelling insights into the potential of flavonoids, particularly KF, as modulators of calcineurin activity. The TAC, with its high binding affinity to the calcineurin complex, aligns with its well-established role as a potent CNI and its clinical efficacy as an immunosuppressant. In comparison, KF does not exhibit the same level of binding affinity as TAC; however, the moderate interaction with calcineurin protein and cyclophilin A suggests its potential as an immunomodulator therapeutic agent. These findings corroborate previous studies highlighting the immunomodulatory properties of KF and other flavonoids (13).

It is important to differentiate between the effect on calcineurin as a complex and its related chains. Flavonoids showed moderate affinity towards the complex and were weak against the CnA and CnB1 heterodimers, except Isoquercetin, which showed marked affinity with the cyclophilin A chain. Notably, Quercetin, a structurally related flavonoid, has been shown to inhibit calcineurin by binding to three critical sites at the junction of CnA, CnB1, and cyclophilin A. These binding sites overlap with those targeted by CsA and TAC, underscoring the importance of this region in calcineurin’s substrate recognition and enzymatic activity (14). This discovery reinforces the potential of flavonoids as effective CNIs with therapeutic implications (9, 14, 15).

In this context, KF has shown selectivity in inhibiting the phosphatase activity of calcineurin. It can bind directly to the catalytic domain of CnA, independent of the matchmaker dimer, and suppresses interleukin-2 (IL-2) gene expression in Jurkat T-cells. Additionally, KF unexpectedly blocks tumour necrosis factor-alpha (TNFα)-induced nuclear factor-kappa B (NF-κB) activation in HEK293 cells (16). These findings highlight KF's dual role as both an immunomodulatory agent targeting calcineurin-dependent pathways and a broader anti-inflammatory compound.

The TAC, a potent CNI used post-transplantation, is known for its adverse effects, notably hyperglycemia. Its PKs are influenced by genetic factors and drug interactions, impacting its therapeutic window. It is metabolized by CYP3A and transported by P-gp, exhibiting variability in its clearance. The present study indicates that 30 days of KF use induces P-gp/CYP3A4 activity, potentially enhancing TAC clearance (17, 18).

Understanding the mechanisms behind TAC-induced hyperglycemia is crucial for effective management. Healthcare professionals can then implement strategies to mitigate hyperglycemia, improving patient outcomes and quality of life (19, 20). The study assessed TAC-induced hyperglycemia using biomarkers in serum and pancreatic tissues. Monitoring glucose biomarkers alongside therapeutic drug monitoring is crucial. This integrated approach can optimize patient outcomes and reduce TAC-related hyperglycemia risks (21).

Diabetes mellitus (DM) development and its complications are intricately tied to oxidative stress, marked by an imbalance between reactive oxygen species (ROS) production and antioxidant defenses (22). Hyperglycemia triggers the generation of ROS through multiple pathways. These ROS inflict damage on cellular components, including DNA, proteins, and lipids, thereby contributing to tissue injury and dysfunction (23, 24). Therefore, targeting oxidative stress pathways may offer therapeutic potential for preventing or mitigating DM-related complications (25, 26).

The MDA, SOD, and reduced GSH are established indicators of drug-induced oxidative stress. The TAC was found to exacerbate these parameters, indicating heightened oxidative stress. However, concurrent administration of KF prevented these changes, demonstrating its protective effect against TAC-induced hyperglycemia through antioxidant mechanisms (24).

Furthermore, TAC may contribute to insulin resistance by affecting glucose uptake in peripheral tissues, which is mediated through the endocytosis of glucose transporter type 4 (GLUT4) (27). Regardless of the mechanism, KF attenuated TAC-induced low insulin levels. As a heterodimeric protein composed of noncovalently attached catalytic (CnA) and regulatory (CnB1) subunits, each subunit and isoform of calcineurin contributes uniquely to both normal immune function and adverse effects (28). Gooch et al. demonstrated that transgenic mice lacking the CnAα isoform could reproduce the histological features of nephrotoxicity, while the loss of the β isoform did not (29). Recently, in an in vivo model of nephrotoxicity, Ali et al. found that CnB1 expression levels were low in kidney tissue following TAC use (30). The pathophysiological roles of CnB1 in the pancreas and its association with hyperglycemia have not been extensively investigated. Most studies have focused on measuring the influence of TAC on calcineurin phosphatase activity rather than its expression level in vital tissues. It has been reported that oxidants and oxidative actions could induce conformational changes within calcineurin, leading to the inactivation of the phosphatase enzyme (31).

In our TAC-treated rats, the pancreatic concentration of CnB1 has markedly decreased. This finding may offer valuable insight into a novel pathway rationalized by drug-induced oxidative stress. In the present study, KF has been selected as a natural antioxidant flavonol intended to protect the pancreas from toxicity associated with CNI treatment (32, 33). The concomitant administration of KF and TAC effectively mitigates TAC-induced hyperglycemia and oxidative stress, accompanied by a significant enhancement in CnB1 expression in pancreatic tissues. These findings align with previous in vitro studies conducted on purified calcineurin, which suggested that specific antioxidants like ascorbate and GSH could enhance calcineurin's phosphatase activity (34). In contrast, findings from a study conducted on Jurkat T-cells and purified enzyme suggest that both KF and its quercetin metabolite demonstrate direct non-competitive inhibition of calcineurin phosphatase activity, alongside a reduction in IL-2 gene expression (35, 36). Regardless of this debate, our findings suggest the possibility that KF and other flavonoids may act as weak CNIrs with potential antioxidant benefits; however, these observations are preliminary and require further verification.

5.1. Conclusions

In relation to TAC-associated hyperglycemia, our MD results suggest that KF and possibly similar flavonoids have the potential to interact with both CnA, CnB1, and cyclophilin A, providing a plausible mechanistic basis for their influence on calcineurin-related pathways. Notably, despite maintained TAC serum levels, co-administration of KF appeared to attenuate multiple markers of TAC-induced hyperglycemia and oxidative stress, while also preventing TAC-related suppression of CnB1 expression in pancreatic tissues. These observations are preliminary and require further validation, but they raise the possibility that KF and other similar flavonoids could have therapeutic potential as an adjuvant alongside CNIs or as an immunomodulator. Flavonoids generally exhibit a better safety profile, but suffer from poor lipophilicity, low Vd, and limited access to intracellular targets. Glycosylated flavonoids are even less likely to reach intracellular compartments due to increased polarity and reduced lipophilicity, and need an advanced delivery system.

5.2. Limitations and Future Work

This preliminary study has several limitations. Only a limited number of flavonoids were evaluated through MD, which restricts the generalizability of the findings. Expanding the compound database is therefore recommended to enable broader screening and structure-activity relationship analysis. Additionally, molecular dynamics simulations were not performed, which could have provided more profound insights into the stability and conformational flexibility of the ligand-protein complexes. Future studies should also include in vitro assays to confirm calcineurin inhibition, supported by histological and immunohistochemical analyses to assess tissue-level effects. Integrating these experimental approaches will strengthen the mechanistic understanding and translational relevance of the computational results.