1. Background

The genus Dracocephalum comprises approximately 60 species (1). Various species in this genus are annual plants belonging to the Lamiaceae family, originating from Central Asia and also found in regions of Central and Eastern Europe. Many plants in this family are of significant economic value and are regarded as medicinal due to the presence of bioactive constituents (2). Dracocephalum lindbergii, a lesser-studied member of this genus, also belongs to the Lamiaceae family (2, 3). It is a perennial herb that primarily grows in the mountainous, cold, and arid climates of the Khorasan region in Iran and parts of Afghanistan. Its leaves are arranged oppositely and typically have finely toothed margins. The flowers form in clusters at the ends of central and lateral stems, often exhibiting purple or pale blue hues. The calyx bears distinct teeth, and the bilabiate corolla structure is a notable morphological feature of the Dracocephalum genus (4).

Few studies have investigated the phytochemistry and biological properties of D. lindbergii essential oil. A recent in vitro investigation by Khamsipour et al. demonstrated its effects on inhibition, induction of apoptosis, and modulation of cytokines in Leishmania major (5). Gas chromatography-mass spectrometry (GC-MS) analysis of the essential oil from D.kotschyi in other species identified α-pinene, limonene, and β-caryophyllene. Furthermore, its cytotoxic effects on U87 cell lines were shown to be dose- and time-dependent, primarily through the production of elevated reactive oxygen species (ROS) (6).

2. Objectives

Given the diverse bioactive compounds present in various Dracocephalum species, which are known for their antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, and anticancer properties, and considering the limited research on D. lindbergii, this study aims to investigate the genotoxic potential of its essential oil using an in vitro human umbilical vein endothelial cell (HUVEC) model. It is acknowledged that further in vivo validation will be necessary to assess the clinical relevance of these findings.

3. Methods

3.1. Plant Material

The above-ground parts of the plant were collected in late June from the Khorasan Razavi area in Iran. Dr. Mohammad Reza Joharchi authenticated and identified the plant material, which was subsequently deposited in the herbarium at the School of Pharmacy, Isfahan University of Medical Sciences, under the voucher number 4050-SAM.

3.2. Essential Oil Preparation

The dried plant material was ground using an electric mill to facilitate essential oil extraction. A total of 120 grams of the powdered plant was placed into a 2-liter distillation flask, and 1,200 mL of deionized water was added. The mixture underwent hydro-distillation with a Clevenger-type apparatus for 3 hours. This procedure was repeated five times, each time using a fresh batch of plant material, to collect a sufficient quantity of essential oil. The collected oil fractions were pooled, dried over anhydrous sodium sulfate to remove residual moisture, and stored in a tightly sealed dark glass container under refrigerated conditions until further analysis (7, 8).

3.3. Essential Oil Gas Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry Screening

The identification and analysis of essential oils were conducted using a GC-MS system from Agilent Technologies (USA). A 1 µL sample of the essential oil was injected into the GC-MS, and compound identification was achieved by calculating Kovats retention indices and comparing the mass spectra with reference data from spectral libraries. The analysis utilized an HP-5 capillary column (30 m in length, 0.25 mm in inner diameter, and 0.25 µm in film thickness) with high-purity helium (99.9999%) as the carrier gas. The flow rate was set at 17.7 mL/min, and the ionization energy of the mass spectrometer was 70 eV. The oven temperature program was as follows: It started at 70°C, was held for 2 minutes, and then increased gradually at a rate of 3°C/min until reaching a final temperature of 240°C (9).

3.4. MTT Assay for Evaluating Cytotoxicity of Essential Oil on Human Umbilical Vein Endothelial Cells

A culture flask containing HUVEC, originally obtained from the Pasteur Institute in Tehran, was removed from the incubator and transferred under a laminar flow hood under aseptic conditions. After washing the cells with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS, pH 7.4), 1 mL of trypsin was added to the flask, which was then returned to the incubator for 4 minutes. Subsequently, 2 mL of medium was added to neutralize the trypsin, and the cells were gently pipetted to detach them. The resulting cell suspension was centrifuged at 1800 rpm for 5 minutes. After discarding the supernatant, 5 mL of fresh culture medium was slowly pipetted to resuspend the cells. From this suspension, 3 mL was diluted to a final volume of 20 mL in a 50 mL Falcon tube, according to the required cell density. A concentration of 5,000 cells per mL was prepared for seeding into a 96-well plate. Each well received 180 µL of the prepared cell suspension. The plate was incubated for 24 hours at 37°C to allow for cell attachment. On the second day, 20 µL of various concentrations of essential oil and the respective vehicles for each concentration as controls were added to the corresponding wells. The plate was then incubated for an additional 24 hours. After treatment, 20 µL of MTT solution (0.5 mg/mL) was added to each well, and the plate was incubated for 3 hours at 37°C. Following incubation, the medium in each well was carefully removed, and 150 µL of dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) was added to dissolve the formazan crystals. Absorbance was measured at 570 nm using an ELISA reader (BioTek Instruments, PowerWave XS, Winooski, USA) (10). It should be noted, however, that while the MTT assay is widely used for assessing cell viability via mitochondrial reductase activity, it is known that certain phytochemicals — particularly those with reducing or antioxidant properties — may directly reduce MTT to formazan independent of cellular metabolism.

3.5. Comet Assay

The HUVEC line was used in this study and was sourced from the National Center for Genetic and Biological Resources of Iran. The cells were received in a frozen state and stored at -80°C until required (9). The comet assay, also known as single-cell gel electrophoresis, is a highly sensitive technique for detecting DNA damage at the cellular level. This method can detect both single- and double-strand DNA breaks, as well as DNA damage induced by physical or chemical agents. In this procedure, cells are embedded in agarose gel on microscope slides, lysed under either alkaline or neutral conditions, and then subjected to electrophoresis. Damaged DNA fragments, due to their lower molecular weight (MW), migrate further through the gel, forming a “comet-like” tail structure. The DNA is then stained with fluorescent dyes and visualized under a fluorescence microscope. The comet assay is a widely used standard technique in genetic, oncological, and genotoxicity studies for evaluating DNA damage and repair (11).

3.6. Preparation of Essential Oil Concentrations

To prepare the essential oil stock solution, 95 µg of the oil was dissolved in a mixture of 500 µL DMSO and 500 µL ethanol to achieve a final volume of 1 mL. This solution was then diluted with 8.5 mL of culture medium to obtain a working concentration of approximately 10,000 µg/mL. From this stock, 2 mL was mixed with 8 mL of medium to prepare a 2,000 µg/mL solution. Next, 2 mL of the 2,000 µg/mL dilution was combined with 8 mL of medium to yield a 400 µg/mL solution. For lower concentrations (e.g., 2 µg/mL and 10 µg/mL), serial dilutions were prepared from the 20 µg/mL intermediate solution for greater convenience and precision.

3.7. Hydrogen Peroxide Exposure and Determination of Genotoxic Concentration

To determine the genotoxic concentration of hydrogen peroxide (H2O2), a 200 µM stock solution was prepared. Serial dilutions were then made from this stock to obtain final concentrations of 1, 2, 5, 10, 50, and 100 µM. Since the volume of each well in the 12-well plate was 2 mL, double-strength concentrations were prepared, and 1 mL of each was added to each well to achieve the desired final concentration. For cell exposure, HUVEC were first detached from culture flasks and used to prepare a single-cell suspension. Under aseptic conditions, a sterile 12-well plate was placed in a laminar flow hood. Each well was seeded with 1 mL of cell suspension and 1 mL of complete culture medium, then incubated for 24 hours. After incubation, the wells were inspected under a microscope to confirm cell viability and density. The culture medium was then removed, and 1 mL of each prepared H2O2 concentration was added to the corresponding wells. To ensure homogeneity of the treatment environment, gentle pipetting was performed after adding the test solutions. The plate was then returned to the incubator for an additional 24 hours of exposure (11).

3.8. Cell Exposure to Different Essential Oil Concentrations for Safety Evaluation

To assess the safety range of essential oil concentrations, HUVEC were first detached from culture flasks to prepare a single-cell suspension. Under aseptic conditions, a sterile 12-well plate was transferred into a laminar flow hood. Each well was seeded with 1 mL of the cell suspension and incubated for 24 hours to allow for cell attachment and growth. After incubation, the plate was removed and examined under a microscope to assess cell viability and confluency. In the laminar flow hood, each well was labeled according to the designated essential oil concentration. The spent culture medium was discarded, and 1 mL of fresh complete medium, together with 1 mL of each prepared essential oil dilution, was added to the corresponding wells. For each plate, one well served as the untreated control and received only 2 mL of complete culture medium. To ensure even distribution and exposure of cells, gentle pipetting (by pipetting up and down) was performed after the addition of the essential oil and medium. Finally, the plate was returned to the incubator for an additional 24 hours of exposure (11).

3.9. Assessment of Intracellular Glutathione Levels

Intracellular glutathione (GSH) levels were measured using a KiaZist GSH assay kit. Prepared HUVEC were trypsinized, collected, and the supernatant was removed. Each well was lysed individually with 200 µL of KiaZist lysis buffer. Lysates were then centrifuged at 4°C for 5 minutes at 1200 rpm. A 10 µL aliquot of each supernatant was transferred to a 96-well plate, with the lysis buffer serving as the blank control. Subsequently, 2 µL of thiol reagent and 198 µL of KiaZist thiol buffer were added to each well. After 15 minutes of incubation at room temperature, absorbance was measured at 405 nm using an ELISA plate reader (12).

3.10. Assessment of Intracellular Reactive Oxygen Species Levels

To prepare the working solution of 2',7'-dichlorofluorescin diacetate (DCFDA) reagent, 10 µL of DCFDA reagent was mixed with 10 mL of ROS buffer. Additionally, the control solution of oxidized DCFDA was prepared by combining 1 µL of oxidized DCFDA with 1 mL of ROS buffer. After cell preparation, 20 µL of each essential oil concentration was added to the wells, followed by gentle pipetting to ensure proper mixing. The plates were then incubated for 24 hours. After incubation, the culture medium was removed. Except for the negative control wells, 20 µL of freshly prepared 5 µM H2O2 was added to each well. Four wells were designated as positive controls, containing cells treated with 200 µM H2O2. On the fourth day, cells were removed from the incubator, rinsed with ROS buffer, and 100 µL of the DCFDA working solution was applied to each well. The plate was incubated in the dark at 37°C for 45 minutes. To confirm assay performance, 100 µL of oxidized DCFDA solution was added to two separate wells as a technical control. After incubation, the staining solutions were removed, and 200 µL of ROS buffer was added to each well. The fluorescence intensity was then measured at an excitation/emission wavelength of 485/535 nm (13).

3.11. Absorption, Distribution, Metabolism, Excretion, and Toxicity Properties Predictions

In the early stages of the drug discovery process, evaluating absorption, distribution, metabolism, excretion, and toxicity (ADMET) is crucial for the development of safe and efficacious drugs (14). In this study, the physicochemical properties of the essential oil compounds from D. lindbergii — including MW, number of hydrogen bond donors (HBDs), number of hydrogen bond acceptors (HBAs), lipophilicity (logP), and drug-likeness according to Lipinski’s rule of five — were assessed using the SwissADME web tool (15). Additionally, the admetSAR database was employed to predict pharmacokinetic characteristics such as human intestinal absorption (HIA), blood-brain barrier (BBB) permeation, P-glycoprotein (P-gp) substrate status, distribution (subcellular localization), metabolism (cytochrome P enzyme inhibition), and toxicity, including human ether-a-go-go-related gene (hERG) potassium channel inhibition (cardiotoxicity), AMES mutagenicity, and carcinogenicity (16).

3.12. Statistical Analysis

All graphical representations and statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism version 8.0.2. Data are presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD). Statistical comparisons between experimental groups were conducted using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA), followed by Dunnett's post-hoc multiple comparison test to evaluate differences from the control group. A P-value of < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

4. Results

4.1. Gas Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry Analysis of Dracocephalum lindbergii Essential Oil

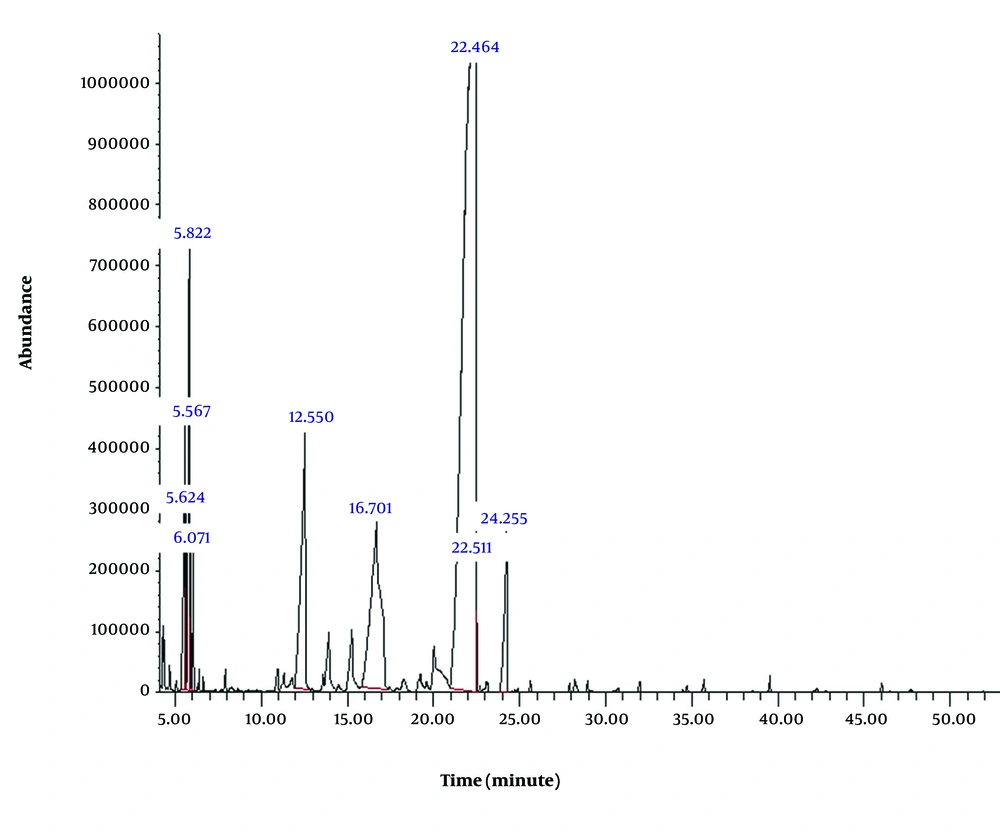

Table 1 presents the total ion chromatogram (TIC) for the essential oil, which was obtained through GC-MS analysis. In addition, Figure 1 provides a graphical representation of the essential oil sample analyzed by GC-MS.

| Compounds | Molecular Formula | Rt (min) | Calculated KI | TIC (%) | Identification Method | Ref. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | l-limonene | C10H16 | 5.560 | 1018 | 3.104 | Mass/KI | (17) |

| 2 | Delta-3-carene | C10H16 | 5.882 | 1032 | 4.294 | Mass/KI | (18) |

| 3 | Unknown | - | 12.550 | 1207 | 8.084 | - | - |

| 4 | Unknown | - | 16.701 | 1256 | 12.350 | - | - |

| 5 | Limonen-10yl-acetat | C12H20O2 | 22.464 | 1384 | 66.362 | Mass/KI | (19) |

| 6 | Germacrene-D | C15H24 | 24.251 | 1515 | 3.131 | Mass/KI | (20) |

| Monoterpenoids: Non-oxygenated | 7.398 | ||||||

| Monoterpenoids: Oxygenated | 66.362 | ||||||

| Sesquiterpenoids | 3.131 | ||||||

| Unknown | 20.434 | ||||||

| Phenylpropanoids | - | ||||||

| Minor compounds | 2.675 | ||||||

Abbreviations: Rt, retention time; TIC, total ion count.

According to the GC-MS analysis, the primary components of the essential oil were identified and classified based on their retention times in the chromatogram. Six principal compounds were detected, including two simple monoterpenes (4.7%), one oxygenated acetylated monoterpene — limonene-10yl-acetate — which serves as the primary active component (66.4%), one simple sesquiterpene (13.3%), and two unidentified compounds accounting for 20.14% of the total composition (Table 1).

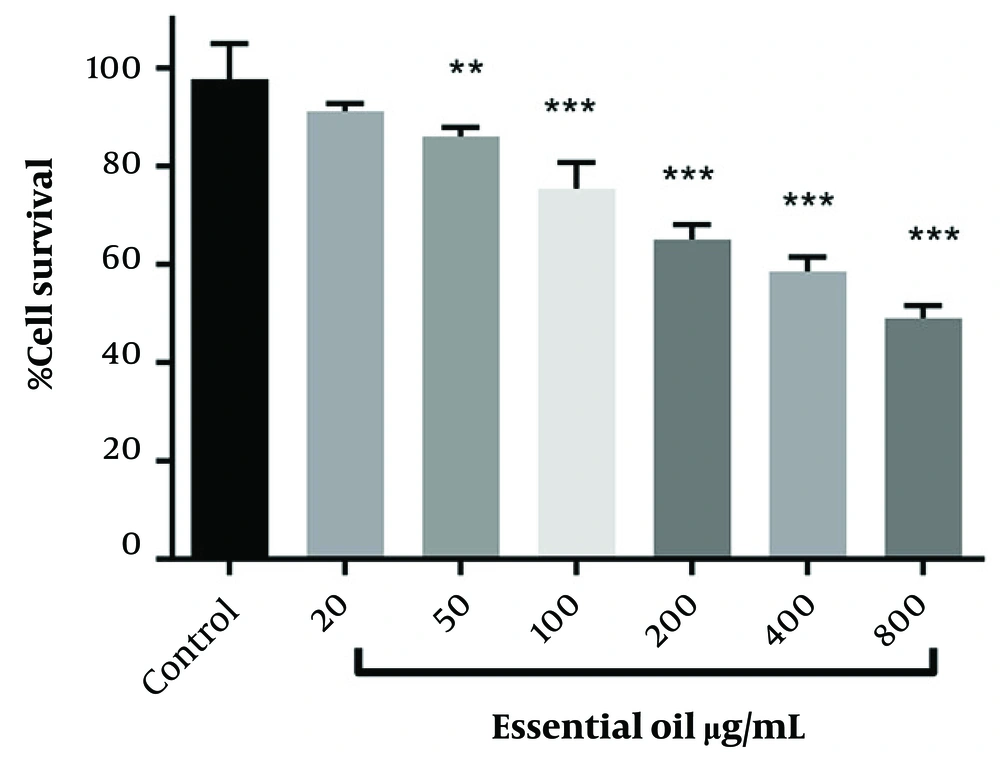

4.2. MTT Survival Assessment

The toxicity of the essential oil of D. lindbergii was evaluated using the standard MTT assay on HUVEC (Figure 2). Cells were incubated with concentrations of 20, 30, 50, 100, 200, 400, and 800 µg/mL of the essential oil for 24 hours. The lowest concentration tested, 20 µg/mL, did not cause significant cytotoxicity. Overall, the essential oil exhibited weak toxicity, with an IC50 value of 707.3 µg/mL.

4.3. Genotoxicity Assessment

Cells were incubated for 24 hours with concentrations of 1, 5, 10, 50, 100, and 200 µg/mL. The results of the comet assay, which evaluated tail length, indicated that the essential oil significantly increased tail length in cells compared to the control group (cells incubated solely in complete culture medium) at all tested concentrations (1, 5, 10, 50, 100, and 200 µg/mL; P < 0.0001). As shown in Figure 3, this effect was concentration-dependent, with a pronounced increase in tail length observed as the essential oil concentration increased. Data are presented as mean ± SEM from four independent replicates. The symbol (****) denotes a statistically significant difference from the control group (P < 0.0001).

4.4. Comparison of DNA in Tail

The comparison of DNA in tails across different concentrations of D. lindbergii essential oil was performed. The HUVECs were incubated with the essential oil for 24 hours. The results of the comet assay demonstrated that the essential oil significantly increased the percentage of DNA in the tail in a concentration-dependent manner at concentrations of 1, 5, 10, 50, 100, and 200 µg/mL when compared to the control group (P < 0.0001). As shown in Figure 4, the maximum percentage of DNA in the tail was observed at a concentration of 200 µg/mL. Results are presented as mean ± SEM, derived from three replicates. The notation (****) indicates a statistically significant difference compared to the control group (P < 0.0001).

Percentage of DNA in comet tails of human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVECs) treated with varying concentrations of Dracocephalum lindbergii essential oil, indicating genotoxicity [The notation (****) indicates a statistically significant difference compared to the control group (P < 0.0001)].

4.5. Comparison of Tail Moment

The comparison of tail moment across various concentrations of D. lindbergii essential oil was conducted. The HUVECs were incubated for 24 hours with concentrations of 1, 5, 10, 50, 100, and 200 µg/mL. The results of the comet assay demonstrated that the essential oil significantly increased the tail moment at all tested concentrations (1, 5, 10, 50, 100, and 200 µg/mL) compared to the control group (P < 0.0001). As illustrated in the chart, this increase was concentration-dependent, with the highest tail moment observed at 200 µg/mL, indicating the greatest extent of DNA damage at this concentration (Figure 5). The results are presented as mean ± SEM, based on three replicates. The notation (****) denotes a statistically significant difference compared to the control group (P < 0.0001).

Comparison of tail moment values in human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVECs) exposed to different concentrations of Dracocephalum lindbergii essential oil, reflecting the extent of DNA damage [The notation (****) denotes a statistically significant difference compared to the control group (P < 0.0001)].

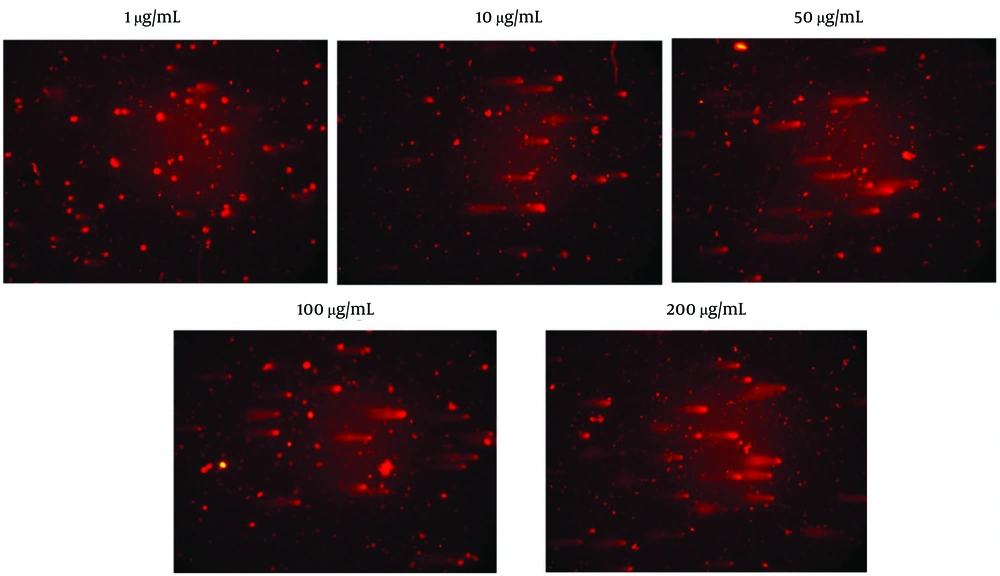

Figure 6 displays comet assay micrographs of HUVEC cells treated with D. lindbergii essential oil following 24 hours of exposure. Cells exposed to the lowest concentration (1 µg/mL) exhibited intact nuclei with minimal comet tail formation, indicating negligible DNA damage. In contrast, cells treated with the highest concentration (200 µg/mL) showed distinct comet tails with extensive DNA migration, reflecting significant genotoxicity.

Representative comet assay micrographs of human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVECs) treated with Dracocephalum lindbergii essential oil for 24 hours. Cells exposed to 1 µg/mL show intact nuclei with minimal comet tail formation, indicating negligible DNA damage. Cells treated with 200 µg/mL exhibit pronounced comet tails with extensive DNA migration, reflecting significant genotoxicity.

4.6. Glutathione Levels in Human Umbilical Vein Endothelial Cells Following with D. lindbergii Essential Oil

The results of GSH measurements following treatment of HUVECs with varying concentrations of D. lindbergii essential oil revealed significant alterations in intracellular GSH levels. The cells were incubated with the essential oil for 24 hours. Subsequently, the culture medium was replaced, and the cells were exposed to 5 µM H2O2 for an additional 24 hours. Exposure to H2O2 resulted in a marked reduction in intracellular GSH. The essential oil, in the presence of H2O2 (5 µM), significantly decreased GSH levels. As shown in Figure 7, GSH levels in the positive control group (H2O2 without essential oil) were significantly lower. In the experimental groups treated with essential oil concentrations of 1, 5, 10, 50, and 100 µg/mL, a statistically significant reduction in GSH levels was observed compared to the negative control group (P < 0.0001). Results are presented as mean ± SEM from three replicates. The notation (****) indicates a statistically significant difference compared to the control group (P < 0.0001).

Intracellular glutathione (GSH) levels in human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVECs) treated with Dracocephalum lindbergii essential oil and hydrogen peroxide (H2O2, 5 µM), demonstrating antioxidant depletion [The notation (****) indicates a statistically significant difference compared to the control group (P < 0.0001)].

4.7. Intracellular Reactive Oxygen Species Levels in Human Umbilical Vein Endothelial Cells Following Treatment with D. lindbergii Essential Oil

The HUVECs were incubated for 24 hours with various concentrations of D. lindbergii essential oil. After replacing the culture medium, the cells were exposed to 5 µM H2O2 for an additional 24 hours. Exposure to H2O2 resulted in a marked increase in intracellular ROS. Assessment of intracellular ROS levels demonstrated that the essential oil significantly elevated ROS in the presence of H2O2 (5 µM). As shown in Figure 8, fluorescence intensity indicative of ROS production was substantially increased in the positive control group (H2O2 without essential oil). Furthermore, treatment with different concentrations of essential oil (1, 5, 10, 50, and 100 µg/mL) led to a notable increase in ROS levels compared to the negative control group (P < 0.0001, Figure 8). Results are presented as mean ± SEM from three replicates. The notation (****) indicates a statistically significant difference compared to the control group (P < 0.0001).

Intracellular reactive oxygen species (ROS) levels in human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVECs) co-treated with Dracocephalum lindbergii essential oil and hydrogen peroxide (H2O2, 5 µM), indicating oxidative stress induction [The notation (****) indicates a statistically significant difference compared to the control group (P < 0.0001)]

4.8. Absorption, Distribution, Metabolism, Excretion, and Toxicity Prediction of the D. lindbergii Essential Oil Main Compounds

Lipinski’s rule of five states that a compound with a MW > 500, number of HBAs > 10, number of HBDs > 5, and MlogP > 4.15 is likely to exhibit poor absorption or permeability (21). As shown in Table 2, according to Lipinski’s rule, all essential oil compounds of D. lindbergii, including l-limonene, limonene-10yl-acetate, germacrene, and d-3-carene, are considered drug-like. Furthermore, admetSAR predictions (Table 3) indicate that these compounds have HIA and are able to cross the BBB. Among them, only d-3-carene is predicted to be a likely substrate of P-gp. Most of these compounds are predicted to be localized in the lysosome, except for limonene-10yl-acetate, which is predicted to be localized in the mitochondria. None of these compounds are predicted to inhibit cytochrome P450 (CYP450) isoforms (1A2, 2C9, 2D6, 2C19, 3A4), although d-3-carene may be a substrate of CYP450 3A4, the most abundant CYP450 isoform responsible for metabolizing the majority of pharmaceutical compounds (22). With respect to toxicity, all compounds are considered weak inhibitors of the hERG potassium channel, which plays a critical role in the regulation of cardiac rhythm (23). They are predicted to be non-carcinogenic and non-AMES toxic.

| Compounds | MW (g/mol) | HBA | HBD | MlogP | Drug Likeness (Lipinski) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| l-Limonene | 136.23 | 0 | 0 | 3.27 | Yes; 0 violation |

| Limonene-10yl-acetate | 194.27 | 2 | 0 | 2.56 | Yes; 0 violation |

| Germacrene | 204.35 | 0 | 0 | 4.53 | Yes; 1 violation: MLOGP>4.15 |

| d-3-Carene | 136.23 | 0 | 0 | 4.29 | Yes; 1 violation: MLOGP>4.15 |

Abbreviations: MW, molecular weight; HBA, hydrogen bond acceptor; HBD, hydrogen bond donor.

| Models | l-Limonene | Limonene-10yl-acetate | Germacrene | d-3-Carene |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Absorption | ||||

| Blood–brain barrier | BBB+ | BBB+ | BBB+ | BBB+ |

| Human intestinal absorption | HIA+ | HIA+ | HIA+ | HIA+ |

| P-gp substrate | Non-substrate | Non-substrate | Non-substrate | Substrate |

| Distribution | ||||

| Subcellular localization | Lysosome | Mitochondria | Lysosome | Lysosome |

| Metabolism | ||||

| CYP450 2C9 substrate | Non-substrate | Non-substrate | Non-substrate | Non-substrate |

| CYP450 2D6 substrate | Non-substrate | Non-substrate | Non-substrate | Non-substrate |

| CYP450 3A4 substrate | Non-substrate | Non-substrate | Non-substrate | Substrate |

| CYP450 1A2 inhibitor | Non-inhibitor | Non-inhibitor | Non-inhibitor | Non-inhibitor |

| CYP450 2C9 inhibitor | Non-inhibitor | Non-inhibitor | Non-inhibitor | Non-inhibitor |

| CYP450 2D6 inhibitor | Non-inhibitor | Non-inhibitor | Non-inhibitor | Non-inhibitor |

| CYP450 2C19 inhibitor | Non-inhibitor | Non-inhibitor | Non-inhibitor | Non-inhibitor |

| CYP450 3A4 inhibitor | Non-inhibitor | Non-inhibitor | Non-inhibitor | Non-inhibitor |

| Toxicity | ||||

| hERG inhibition | Weak inhibitor | Weak inhibitor | Weak inhibitor | Weak inhibitor |

| AMES toxicity | Non-AMES toxic | Non-AMES toxic | Non-AMES toxic | Non-AMES toxic |

| Carcinogens | Non-carcinogens | Non-carcinogens | Non-carcinogens | Non-carcinogens |

Abbreviations: BBB, blood-brain barrier; HIA, human intestinal absorption; P-gp, P-glycoprotein; CYP450, cytochrome P450; hERG, human ether-a-go-go-related gene.

On the other hand, according to the comet assay performed in our study, treatment of HUVEC cells with the essential oil did not induce DNA damage at low concentrations, whereas genotoxicity was observed at doses exceeding 10 µg/mL (Figures 3 and 4). In addition, the essential oil in the presence of H2O2 caused a significant decrease in GSH and an increase in intracellular ROS levels, indicating its oxidative potential (Figures 7 and 8). While these compounds exhibit desirable pharmacokinetic properties, they must be administered at limited doses due to toxicity concerns; therefore, in vivo toxicity studies are strongly recommended for further safety assessment.

5. Discussion

The phytochemical profile of the sample reveals a widespread presence of terpenoid compounds in D. lindbergii. The most dominant component is limonene-10yl-acetate, comprising 66.362% of the TIC, indicating that this compound is the primary and most significant constituent of the essential oil. Additionally, two unidentified compounds, with TIC percentages of 8.084% and 12.350%, suggest the existence of other active constituents that have yet to be characterized and may potentially contribute to the biological activities of the extract. Common terpenoids identified include limonene and delta-3-carene, both monoterpenes with the molecular formula C10H16. These compounds were observed at retention times of approximately 5.56 and 5.88 minutes, respectively, with TIC values of 3.104% and 4.294%, indicating their presence in moderate amounts but not as dominant components. Germacrene, a sesquiterpene, was detected at 24.25 minutes with a TIC of 3.131%, confirming its minor but noteworthy contribution to the overall composition. Other minor compounds, totaling around 2.675% TIC, further reflect the complex and multifaceted nature of the extract. Overall, the phytochemical makeup demonstrates that monoterpenoid compounds, particularly limonene-10yl-acetate, constitute the core of this essential oil and may play a key role in its biological properties.

As detailed in the results section (Figures 3 - 5), genotoxic effects were concentration-dependent, becoming significant at doses ≥ 10 µg/mL. While limonene-10yl-acetate was identified as the predominant compound (66.362% TIC), and ADMET predictions suggest mitochondrial localization and drug-like behavior, the contribution of individual compounds such as limonene, d-3-carene, and germacrene could not be independently quantified in this assay format. Moreover, the presence of two unidentified compounds (20.434% TIC) further complicates attribution to specific constituents.

A review of the safety and genotoxicity profiles of the essential oil’s major constituents provides additional context for interpreting the observed biological effects. Limonene-10-yl-acetate, the dominant compound (66.4% TIC), is a monoterpenoid ester commonly found in citrus oils and fragrance formulations. Although direct genotoxicity data on this compound are limited, regulatory assessments by the European Food Safety Authority (EFSA) and the Research Institute for Fragrance Materials (RIFM) indicate no genotoxic concerns for structurally similar acetate esters, based on in vitro assays such as the Ames test and micronucleus assay (24, 25). L-Limonene (3.1% TIC), a well-characterized monoterpene, has demonstrated antigenotoxic and antioxidant properties in human lymphocytes and fibroblasts, with studies showing its protective effects against oxidative DNA damage (26, 27). Germacrene-D (3.13% TIC), a sesquiterpene frequently found in aromatic plants, has not been classified as mutagenic or carcinogenic and is widely used in flavoring and fragrance applications (28). Delta-3-carene, a bicyclic monoterpene, has been shown to irritate skin and mucous membranes (29).

According to the study by Kevic Desic et al., delta-3-carene — identified as one of the major allergens in turpentine — may contribute to the genotoxic effects observed in painters occupationally exposed to turpentine vapors. Although the study does not isolate delta-3-carene specifically, the significant increase in micronuclei, nuclear buds, and nucleoplasmic bridges in exposed individuals suggests that components like delta-3-carene may play a role in genome instability through prolonged inhalation exposure (30). Collectively, these data suggest that while l-limonene, delta-3-carene, and germacrene-D each present some toxicity risk, limonene-10-yl-acetate warrants further targeted toxicological evaluation, particularly given its abundance and the mitochondrial localization predicted by ADMET analysis. The high percentage of this ester suggests it may be highly relevant to the plant's medicinal or aromatic properties. The presence of unidentified compounds further underscores the need for comprehensive characterization, as these may also possess unique bioactivities.

This phytochemical profile is consistent with the typical features of essential oils rich in monoterpenes and sesquiterpenes, which are known for their antimicrobial, anti-inflammatory, and antioxidant properties. A comparable study investigated the essential oils obtained from D.integrifolium Bunge grown in three different regions of northwest China. The chemical composition revealed prominent terpenoid constituents, primarily sabinene and eucalyptol. These major components exhibited notable phytotoxic, antimicrobial, and insecticidal activities (31).

Although the comet assay is a sensitive and widely accepted method for detecting DNA strand breaks, it captures damage at a single time point and does not distinguish between direct genotoxicity and secondary effects such as apoptosis or necrosis. To better elucidate the underlying mechanism, we complemented the comet assay with assessments of intracellular oxidative stress. Treatment with D. lindbergii essential oil led to a significant increase in ROS and a marked depletion of GSH, indicating that oxidative stress is a key mediator of DNA damage. These findings align with previous studies demonstrating that elevated ROS levels can induce oxidative DNA lesions, including the formation of 8-oxoguanine and single-strand breaks, both of which are detectable by the comet assay (32).

Importantly, genotoxic effects were observed at concentrations ≥ 10 µg/mL, which are well below the IC50 value of 707.3 µg/mL determined by the MTT assay. This suggests that DNA damage occurs prior to overt cytotoxicity and is not merely a consequence of cell death. While apoptosis markers were not evaluated in this study, the absence of significant cytotoxicity at genotoxic doses argues against apoptosis as the primary cause. Furthermore, ADMET predictions indicated mitochondrial localization for limonene-10-yl-acetate, the major constituent of the oil, suggesting that mitochondrial ROS generation may serve as a plausible upstream event. Mitochondrial dysfunction and ROS overproduction have been implicated in DNA damage and cellular stress responses in various model systems (33, 34). Collectively, these results support an indirect, oxidative stress-mediated mechanism of genotoxicity and underscore the need for future studies involving apoptosis markers, mitochondrial membrane potential assays, and DNA repair profiling to fully elucidate the biological pathways involved.

A gas chromatography liquid analysis of D.moldavica essential oil revealed a composition of up to 36 distinct constituents, with citral identified as the primary compound. Significant quantities of non-cyclic monoterpenoids — including terpineol, linalyl acetate, geranyl acetate, limonene, linalool, nerol, and geraniol — were also detected, collectively accounting for approximately 35% of the oil content. These compounds contribute to the oil's aromatic profile and may play important roles in its biological activity (35). In a separate investigation, GC-MS analysis of the essential oil of D.kotschyi identified 11 key compounds that accounted for 91.5% of the total composition. The most abundant compounds were copaene (22.15%), methyl geranate (16.31%), geranial (13.78%), and carvone (11.34%).

Retention times ranged from 3.76 to 16.80 minutes. Oxygenated monoterpenoids dominated the profile, comprising 53.77%, followed by sesquiterpenoids at 22.15%, phenylpropanoids at 6.80%, and non-oxygenated monoterpenoids at 8.19%. The presence of minor compounds below 1% was also noted, reflecting the complex nature of the oil (9).

Based on the findings, the study confirms that D. lindbergii essential oil exhibits notable genotoxic effects in HUVECs across a range of concentrations. Significant observations include a substantial increase in tail length, tail DNA percentage, and tail moment, all indicative of DNA damage. Tail length showed a significant increase at concentrations between 1 and 200 µg/mL, demonstrating a clear dose-dependent relationship in which higher concentrations resulted in more extensive DNA damage. Similarly, the proportion of DNA present in the tail was markedly higher throughout the same concentration range, with the peak value observed at 200 µg/mL, indicating the highest level of genotoxic effect. The Tail Moment Index, a quantitative measure of DNA damage, also increased markedly with rising essential oil concentrations, peaking at 200 µg/mL. These patterns collectively suggest that the essential oil induces DNA strand breaks in a concentration-dependent manner, underscoring its potential for genotoxicity.

The effect of D. lindbergii essential oil on oxidative stress indicators was assessed by quantifying intracellular GSH and ROS in HUVEC cells. The H2O2 (5 µM) alone caused a notable decrease in GSH concentrations, indicating oxidative stress. When various concentrations of the essential oil were administered to the treated cells, a comparable and statistically significant decrease in GSH was observed, further indicating disruption of the cellular antioxidant defense system. In parallel, the production of intracellular ROS was markedly elevated upon exposure to H2O2. The addition of the essential oil at different concentrations led to an even greater increase in ROS levels, not only surpassing the negative control group but also exceeding the ROS level in the H2O2-only positive control. These findings suggest that the essential oil, when combined with H2O2, amplifies ROS generation and may contribute to increased oxidative stress and cellular damage.

While HUVECs provide a relevant endothelial model for assessing oxidative and genotoxic responses, they represent an in vitro system with inherent limitations. The observed DNA damage and oxidative stress responses may not fully translate to in vivo conditions due to differences in metabolism, tissue interactions, and systemic clearance. Therefore, these findings should be interpreted as preliminary, and further studies using animal models and clinical data are essential to confirm the safety and genotoxic potential of D. lindbergii essential oil in humans.

The findings of this study underscore the concentration-dependent genotoxic and oxidative effects of D. lindbergii essential oil, particularly at doses exceeding 10 µg/mL. This highlights the dual nature of plant-derived compounds, which may exhibit therapeutic or toxic effects depending on dose and composition. In contrast, recent studies — such as the investigation of Arbutus andrachne essential oil — have demonstrated antioxidant and antiproliferative properties with minimal cytotoxicity, reinforcing the importance of species-specific and dose-dependent toxicity (36). Similarly, the essential oil of pomelo peel, which is also rich in limonene, has shown antioxidant and antibacterial activities and has been evaluated for cosmetic applications with established quality standards (37). Another investigation of essential oils from commonly used Iranian spices, such as Trachyspermum copticum and Cuminum cyminum, demonstrated significant antioxidant and antibacterial activities, suggesting their potential utility in maternal health support (38).

5.1. Conclusions

The phytochemical analysis of D. lindbergii essential oil reveals that monoterpenoid compounds, particularly limonene-10yl-acetate, are predominant and likely responsible for its biological properties. This compound stands out as the primary contributor to the oil's bioactivity. Although the MTT assay of the essential oil showed weak toxicity on HUVEC cells with an IC50 of 707.3 µg/mL, experimental observations confirm that increasing concentrations of the essential oil led to notable DNA damage, depletion of intracellular antioxidants such as GSH, and a marked rise in ROS in HUVEC cells. These effects were dose-dependent, with higher concentrations producing more severe genotoxic and oxidative stress responses in the tested cell lines. This dose-related increase in DNA damage, ROS generation, and antioxidant depletion underscores the potential cytotoxic impact of the essential oil under in vitro conditions. However, these in vitro findings should not be extrapolated to humans without further in vivo and clinical validation. Additionally, ADMET predictions indicated that the main constituents of the essential oil are drug-like and have favorable pharmacokinetic properties without predicted toxicity. These results can be useful for designing in vivo studies and developing pre-formulations for clinical trial studies of the essential oil of this plant. As such, further research is warranted to assess in vivo toxicity, characterize unidentified constituents, and elucidate the molecular pathways involved. This will help ensure the safe and informed use of D. lindbergii essential oil.

![Comet tail length in human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVECs) treated with varying concentrations of <i>Dracocephalum lindbergii</i> essential oil [The symbol (****) denotes a statistically significant difference from the control group (P < 0.0001)]. Comet tail length in human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVECs) treated with varying concentrations of <i>Dracocephalum lindbergii</i> essential oil [The symbol (****) denotes a statistically significant difference from the control group (P < 0.0001)].](https://services.brieflands.com/cdn/serve/31710/7ed1f71ba9684fccfa6f607094e37012bd696d10/jrps-13-1-165509-i003-preview.webp)

![Percentage of DNA in comet tails of human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVECs) treated with varying concentrations of <i>Dracocephalum lindbergii</i> essential oil, indicating genotoxicity [The notation (****) indicates a statistically significant difference compared to the control group (P < 0.0001)]. Percentage of DNA in comet tails of human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVECs) treated with varying concentrations of <i>Dracocephalum lindbergii</i> essential oil, indicating genotoxicity [The notation (****) indicates a statistically significant difference compared to the control group (P < 0.0001)].](https://services.brieflands.com/cdn/serve/31710/72dba133cfbda737d480102bd0a1f2c6e47ddae5/jrps-13-1-165509-i004-preview.webp)

![Comparison of tail moment values in human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVECs) exposed to different concentrations of <i>Dracocephalum lindbergii</i> essential oil, reflecting the extent of DNA damage [The notation (****) denotes a statistically significant difference compared to the control group (P < 0.0001)]. Comparison of tail moment values in human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVECs) exposed to different concentrations of <i>Dracocephalum lindbergii</i> essential oil, reflecting the extent of DNA damage [The notation (****) denotes a statistically significant difference compared to the control group (P < 0.0001)].](https://services.brieflands.com/cdn/serve/31710/0b63857e9713b60ad86383668aa17f1b6f43b551/jrps-13-1-165509-i005-preview.webp)

![Intracellular glutathione (GSH) levels in human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVECs) treated with <i>Dracocephalum lindbergii</i> essential oil and hydrogen peroxide (H<sub>2</sub>O<sub>2</sub>, 5 µM), demonstrating antioxidant depletion [The notation (****) indicates a statistically significant difference compared to the control group (P < 0.0001)]. Intracellular glutathione (GSH) levels in human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVECs) treated with <i>Dracocephalum lindbergii</i> essential oil and hydrogen peroxide (H<sub>2</sub>O<sub>2</sub>, 5 µM), demonstrating antioxidant depletion [The notation (****) indicates a statistically significant difference compared to the control group (P < 0.0001)].](https://services.brieflands.com/cdn/serve/31710/bdd3658a1f76f3db269f0159aa4229fb6f6792c2/jrps-13-1-165509-i007-preview.webp)

![Intracellular reactive oxygen species (ROS) levels in human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVECs) co-treated with <i>Dracocephalum lindbergii</i> essential oil and hydrogen peroxide (H<sub>2</sub>O<sub>2</sub>, 5 µM), indicating oxidative stress induction [The notation (****) indicates a statistically significant difference compared to the control group (P < 0.0001)] Intracellular reactive oxygen species (ROS) levels in human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVECs) co-treated with <i>Dracocephalum lindbergii</i> essential oil and hydrogen peroxide (H<sub>2</sub>O<sub>2</sub>, 5 µM), indicating oxidative stress induction [The notation (****) indicates a statistically significant difference compared to the control group (P < 0.0001)]](https://services.brieflands.com/cdn/serve/31710/c62fd58429cea71f5cbb7934071155d815e03e7c/jrps-13-1-165509-i008-preview.webp)