1. Background

Drug allergies represent a growing concern in pediatric healthcare, accounting for 5 - 10% of all adverse drug reactions and affecting morbidity, treatment complexity, and overall patient safety (1). Cutaneous adverse drug reactions (CADRs) are the most frequent manifestations of drug allergy and may include urticaria, maculopapular eruptions, angioedema, and purpura, among others (2). The severity of these reactions varies widely, ranging from mild rashes to life-threatening conditions such as Stevens-Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis (3). The underlying immunopathogenesis involves both immunoglobulin E (IgE)-mediated mechanisms (e.g., for urticaria) and T-cell-mediated mechanisms (e.g., for maculopapular exanthema) (4).

Antibiotics, especially beta-lactams, anticonvulsants such as carbamazepine and phenytoin, and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) are among the most frequently implicated agents in pediatric drug reactions (5). The use of herbal medicines, which is common in many communities, is an under-recognized cause of CADRs, often complicating diagnosis due to variable composition and lack of regulation (6).

Epidemiological patterns of drug allergies differ among populations due to variations in prescribing practices, genetic predisposition, and environmental exposures (7). A family history of drug allergy is a well-established risk factor, reflecting underlying genetic susceptibilities (8), and is particularly relevant in populations with unique genetic backgrounds, such as Iran.

Incorrect labeling of drug allergies in children may lead to avoidance of first-line therapies and has been linked to increased antimicrobial resistance, poorer health outcomes, and escalated healthcare costs (9). Despite these challenges, there remains a paucity of epidemiological data regarding drug allergy manifestations and drug use history in pediatric patients from Middle Eastern countries, including Iran (10). To our knowledge, this is one of the first hospital-based investigations of pediatric drug allergy patterns in southeastern Iran. Conducting such studies is essential to better understand regional variations and improve diagnostic accuracy and management strategies.

2. Objectives

This study aimed to investigate the prevalence, clinical characteristics, and associated risk factors of drug-induced cutaneous allergic reactions among pediatric patients in Zahedan, Iran, to inform local pharmacovigilance and pediatric prescribing practices.

3. Methods

This prospective, cross-sectional study was conducted at the Pediatric Department of Imam Ali ibn Abi Talib Hospital, Zahedan, Iran, from January 1 to December 31, 2023. The study population included children presenting with skin rash manifestations suspected to be related to drug allergies. Children of all ages who visited the pediatric department with skin rashes potentially linked to drug hypersensitivity were consecutively recruited.

A total of 245 children were screened, and 210 who met the inclusion criteria were enrolled. This was an observational study without a separate control group; comparisons were made within the cohort. Patients with rashes of confirmed non-drug causes were excluded. These exclusions comprised patients with signs and symptoms indicative of classic viral exanthems (e.g., measles, rubella, varicella, or hand-foot-mouth disease), bacterial infections (e.g., scarlet fever), or systemic inflammatory illnesses (e.g., Kawasaki disease). Exclusion was based on a combination of clinical presentation, laboratory findings (such as leukocyte count, C-reactive protein, and specific serological or polymerase chain reaction (PCR) tests where clinically indicated), and, when available, response to specific non-drug therapies.

A detailed history was obtained from patients and/or their parents or guardians using a structured questionnaire. This included demographic information (age, gender), history of drug exposure preceding rash onset within 4 weeks, types of medications taken (including specific inquiries about herbal and complementary products), timing and characteristics of rash onset, associated symptoms such as fever, and any prior personal or family history of drug allergies. Physical examinations were conducted by a trained pediatrician to document the type and distribution of skin lesions, including urticaria, maculopapular rash, angioedema, purpura, and other cutaneous signs.

The diagnosis of a drug-induced rash was primarily based on a detailed clinical history and a thorough physical examination to establish a temporal association between drug intake and rash onset. To address the critical issue of excluding mimicking conditions, particularly viral exanthems, we implemented a rigorous clinical protocol. Patients with signs and symptoms highly suggestive of a common childhood infection (e.g., high fever preceding the rash, prodromal symptoms, classic presentations of measles, varicella, or hand-foot-mouth disease, or presence of Koplik's spots) were excluded. Furthermore, for cases where the clinical picture was ambiguous, necessary laboratory investigations (such as complete blood count and C-reactive protein) and/or specific serological or PCR tests for suspected pathogens were performed to rule out an infectious cause.

Causality was assessed using the Naranjo Adverse Drug Reaction Probability Scale (11). Regarding confirmatory allergy tests, gold-standard methods such as drug provocation tests were not performed in this study due to ethical considerations. Similarly, skin tests and in vitro tests were not routinely available or validated for all drugs. Reactions were categorized as immediate (onset within 1 hour to 6 hours after drug intake) or non-immediate (onset more than 6 hours after drug intake). In cases of polypharmacy, the culprit drug was identified based on the detailed clinical history and the temporal association between drug intake and rash onset.

The study protocol was reviewed and approved by the Ethics Committee of Zahedan University of Medical Sciences (approval code: IR.ZAUMS.REC.1402.472). Written informed consent was obtained from parents or legal guardians before inclusion.

Data were entered and analyzed using IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 26.0. Descriptive statistics, including frequencies and percentages for categorical variables and means with standard deviations for continuous variables, were computed. Inferential analyses were performed using the chi-square test (or Fisher's exact test where appropriate) to compare the distribution of drug types and rash manifestations across demographic groups. A P-value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant. No imputation was performed for missing data, as all analyzed cases had complete datasets.

4. Results

A total of 210 children were enrolled in this study. The demographic and clinical history characteristics of the participants are summarized in Table 1. The mean age was 7.1 ± 4.3 years, with 51% males (n = 107) and 49% females (n = 103). The majority of participants (82.2%; n = 173) reported a history of drug exposure preceding rash onset.

| Variables | No. (%) |

|---|---|

| Gender | |

| Female | 103 (49) |

| Male | 107 (51) |

| Age (y) | |

| Under 5 | 84 (40) |

| 5 to 10 | 67 (32) |

| Over 10 | 59 (28) |

| Family history of drug allergy | |

| Yes | 90 (43) |

| No | 120 (57) |

| History of drug allergy in child | |

| Yes | 78 (37) |

| No | 132 (63) |

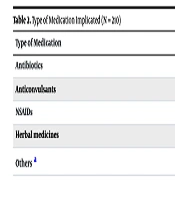

Table 2 presents the types of medications implicated in the allergic reactions. The most frequently implicated medications were antibiotics (32.2%; n = 68), followed by anticonvulsants (27.8%; n = 58), NSAIDs (10.0%; n = 21), and herbal medicines (12.2%; n = 26).

| Type of Medication | No. (%) |

|---|---|

| Antibiotics | 68 (32.2) |

| Anticonvulsants | 58 (27.8) |

| NSAIDs | 21 (10.0) |

| Herbal medicines | 26 (12.2) |

| Others a | 37 (17.6) |

Abbreviation: NSAIDs, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug.

a The "Others" category includes antipyretics (e.g., acetaminophen), cough suppressants, and vitamins.

Table 3 outlines the types of skin manifestations observed. Urticaria and angioedema were the most frequent skin manifestations, occurring in 45.5% (n = 96) of cases, followed by maculopapular rashes in 30.0% (n = 63), and purpura in 5.5% (n = 12).

| Reaction Type | No. (%) |

|---|---|

| Urticaria/angioedema | 96 (45.5) |

| Maculopapular rash | 63 (30.0) |

| Purpura | 12 (5.5) |

| Erythema | 2 (1.1) |

| Other a | 37 (17.6) |

a The "Other" manifestations included fixed drug eruptions, erythema multiforme, and non-specific exanthems.

Urticaria/angioedema was significantly more frequent among boys (68.6% of these cases, P = 0.01), while maculopapular rashes were more commonly seen in girls (46%, P = 0.03). A family history of drug allergy was reported in 43% (n = 90) of participants.

Gender-specific analysis of culprit drugs revealed that antibiotics were the most common culprit in both groups. However, anticonvulsant-induced reactions were significantly more common in females (40.8%, n = 44) than in males (12.2%, n = 13; P < 0.001). All analyzed cases had complete datasets for the reported variables.

5. Discussion

This hospital-based cross-sectional study provides a detailed overview of the clinical patterns and drug allergens responsible for CADRs in a pediatric population from Zahedan, Iran. Our findings underscore the significant burden of drug hypersensitivity in children, identifying antibiotics and anticonvulsants as the predominant triggers, with urticaria and angioedema being the most common clinical presentations. Notable findings include a high rate of reactions to herbal medicines, a strong familial predisposition, and significant gender-based differences in reaction patterns.

Our results are consistent with global and regional data. The predominance of antibiotics and anticonvulsants aligns with longstanding evidence (5, 12). Recent multicenter pediatric pharmacovigilance studies (2023 - 2025) have reported similar gender- and drug-specific patterns of CADRs, reinforcing the need for regionally tailored surveillance systems (13-19).

The significant proportion of reactions attributed to herbal medicines (12.2%) is a critical finding, increasingly recognized in regions with high rates of complementary and alternative medicine use (6). Based on parental reports, the most commonly implicated herbal products were those frequently used in our region for fever, respiratory symptoms, and digestive issues, including preparations containing thyme, chamomile, saffron, and herbal mixtures for 'cold relief'. The allergenic potential of these products can be attributed to several factors. First, the complex biochemical composition of plants includes numerous natural compounds (e.g., sesquiterpene lactones, quinones, and pollens) that can act as haptens and provoke immune responses. Second, and of particular concern, is the risk of product adulteration with undisclosed synthetic drugs (e.g., corticosteroids or NASIDs) or contamination with pesticides, heavy metals, or microbes (18). This underscores a pressing public health concern and highlights the necessity for clinicians to routinely and specifically inquire about herbal product use during medical history-taking.

The strong familial predisposition observed (43%) supports the growing evidence for a genetic component in drug hypersensitivity, linked to specific human leukocyte antigen (HLA) alleles and polymorphisms in drug metabolism enzymes (16, 17). This genetic susceptibility, potentially influenced by the unique allele frequencies in the Iranian population, could partly explain the high prevalence of anticonvulsant reactions we observed. This finding, combined with the high rate of personal allergy history (37%), highlights a subgroup at markedly high risk. For these patients, implementing structured allergy documentation systems and considering pre-prescription screening for high-risk drugs could reduce unnecessary avoidance of first-line therapies and mitigate antimicrobial resistance (17).

Our gender-specific analysis revealed that urticaria/angioedema was more frequent in boys, while maculopapular rashes and reactions to anticonvulsants were significantly more prevalent in girls. Recent immunopharmacology studies suggest that sex-based differences in immune response, influenced by hormonal factors and X-chromosome-related immune genes, may underlie these patterns (15, 16). These findings have direct implications for clinical pharmacy and pharmacovigilance.

This study has several limitations. Its single-center design may limit the generalizability of our findings to other populations with different genetic backgrounds and prescribing practices. Furthermore, the diagnosis of a drug allergy was based on clinical assessment and the Naranjo algorithm, as gold-standard confirmatory tests such as drug provocation tests were not performed for ethical and safety reasons in this clinical setting. This methodological approach, while standard for pharmacovigilance studies, may lead to an overestimation of the true allergy prevalence (9, 18). We also acknowledge the potential for recall bias due to reliance on parent-reported drug histories. Finally, the absence of detailed data on drug dosage, duration of therapy, and indication, which could influence reaction patterns and severity, is another limitation.

Despite these limitations, the findings provide valuable baseline data that can inform multicentric, prospective studies incorporating standardized diagnostic algorithms and genetic testing to establish definitive causal attributions and explore pharmacogenomic risk factors.

5.1. Conclusions

This study supports the predominant role of antibiotics and anticonvulsants in pediatric CADRs, with urticaria and angioedema being the most common manifestations. The high prevalence of reactions to herbal medicines and the strong association with a positive family history are critical findings that underscore the multifactorial nature of drug hypersensitivity. These results emphasize the urgent need for structured pediatric pharmacovigilance systems, clinician training on systematic allergy assessment, and public health initiatives focused on herbal product safety to improve early recognition, accurate reporting, and effective management of drug hypersensitivity in children.