1. Background

A growing body of evidence indicates that epidermal growth factor (EGF) and its receptor play a critical role in wound healing. Activation of the epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) signaling pathway in response to EGF leads to increased production of growth factors, cytokines, and extracellular matrix components, which facilitate tissue repair and regeneration (1, 2). Given its central roles in cell growth, proliferation, and inflammation, EGFR is regarded as a promising target for promoting wound healing.

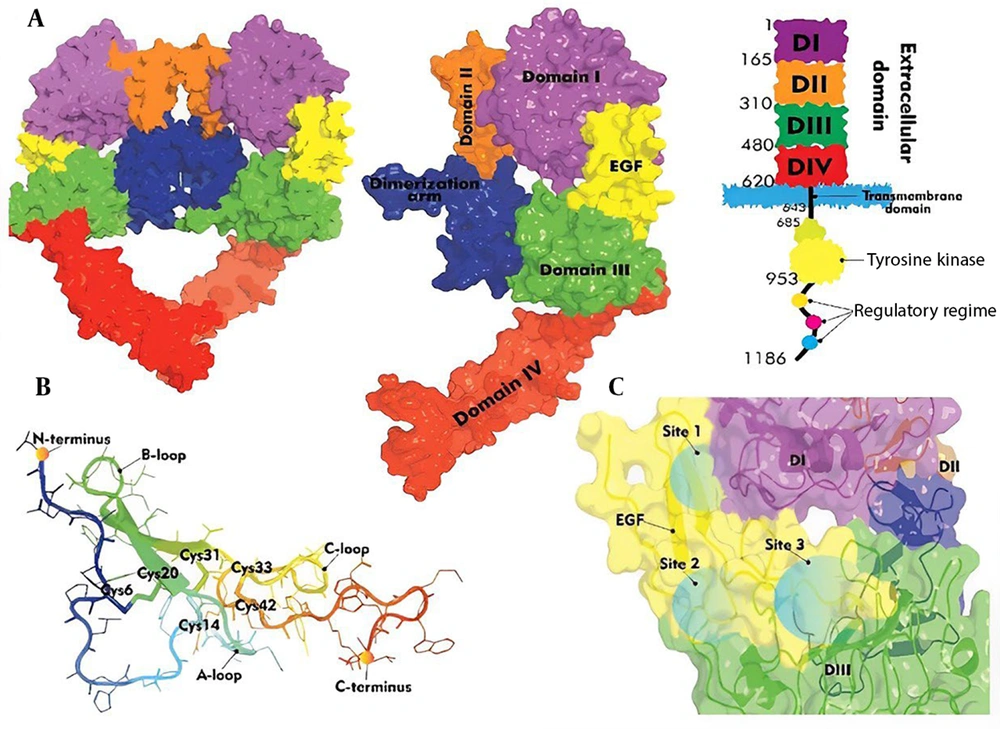

The EGFR consists of an extracellular ligand-binding domain (domains I-IV), a transmembrane domain, and a kinase domain (Figure 1A) (3). Epidermal growth factor, a 53-amino acid peptide with three disulfide bonds, binds to EGFR via three interaction sites (Figure 1B) (4-6). Specifically, the B loop of EGF binds to domain I of EGFR at site I, the A loop of EGF interacts with domain III of EGFR at site II, and the C-terminal tail of EGF interacts with domain III of EGFR at site III (Figure 1C). Site-directed mutagenesis studies have identified critical and conserved residues essential for the binding of EGF to EGFR (7-13). Researchers have extensively investigated this structure-function relationship to enable the design and development of EGF analogues.

2. Objectives

The objective of this study was to use molecular dynamics simulations (MDS) to investigate the interactions between wild-type EGF (WT-EGF) and two engineered EGF mutants (m28-EGF and m123-EGF) (Table 1), which exhibited increased binding affinity to the extracellular domain of EGFR (14). The study explored atomic-level interactions to reveal key structural features underlying enhanced binding affinity, thereby guiding the design of new therapeutics and biomaterials for wound healing.

| Name | Sequence |

|---|---|

| WT-EGF | NSDSECPLSHDGYCLHDGVCMYIEALDKYACNCVVGYIGERCQYRDLKWWELR |

| m28-EGF | NSDSECPLSHDGYCLHGGVCMYIKAVDRYACNCVVGYIGERCQYRDLTWWGPR |

| m123-EGF | NSYSECPPSYDGYCLHDGVCRYIEALDSYACNCVVGYAGERCQYRDLRWWGRR |

a Mutations are in underlined bold type.

3. Methods

In this study, molecular dynamics (MD) simulations were performed on 2EGF/2EGFR complexes containing wild-type and mutant EGFs to theoretically compare their structural dynamics and binding affinities (14-16).

3.1. Preparation of Structures

Mutant EGF structures were generated using MODELLER, based on the WT-EGF crystal structure (PDB: 1JL9) (6, 17), with the best model selected according to energy and Dope score. Model quality was validated using the ERRAT server (18) and PROCHECK program (19). Mutant ligands were docked into the EGFR extracellular domain dimer structure (PDB: 3NJP), and all complexes underwent molecular dynamics simulation.

3.2. Molecular Dynamics Simulation

Simulations of wild-type (WT) and mutant EGF/EGFR complexes were performed using GROMACS 2020 with the AMBER99SB-ILDN force field (20) and the SPC (simple point charge) water model. Systems were solvated in a cubic box with 200 mM NaCl, energy-minimized, and equilibrated under NVT and NPT ensembles at 310 K and 1 bar for 1000 ps. For pressure coupling and temperature, the Parrinello-Rahman algorithms (21) and Berendsen (22) were applied, respectively. Long-range electrostatics were treated using the Particle Mesh Ewald algorithm (18, 23) with a 10 Å cutoff. The linear constraint solver procedure was employed to constrain all bonds connecting hydrogen atoms. Each simulation was run for 100 ns, with trajectories visualized using VMD (24).

Interaction energy analysis was performed with Discovery Studio to assess molecular interactions between EGF ligands and EGFR. The CHARMM force field was used with an implicit dielectric model to determine interaction energy and analyze the stability of ligand-receptor complexes.

4. Results and Discussion

Computational methods were used to examine how wild-type and mutant EGF bind EGFR, evaluating the effects of mutations on binding affinity and EGFR dimer structure.

4.1. Structural Comparison of Epidermal Growth Factor Analogues

The secondary structure of EGF peptides was monitored during simulations to assess folding stability, which is important for EGFR binding. Ramachandran plot analysis showed that 100% of residues in WT EGF, m28-EGF, and m123-EGF models were in favored or allowed regions, confirming high structural quality (Appendices 1 and 3 in Supplementary File).

After MD simulations, secondary structures of WT EGF and mutant were visualized using VMD and analyzed with the STRIDE web server (25). The WT EGF and m28-EGF showed identical secondary structures, while m123-EGF exhibited a slight difference with the formation of a beta-bridge between Ala38 and Tyr44 (Appendix 2 in Supplementary File). This indicates minor conformational changes in the m123-EGF mutant.

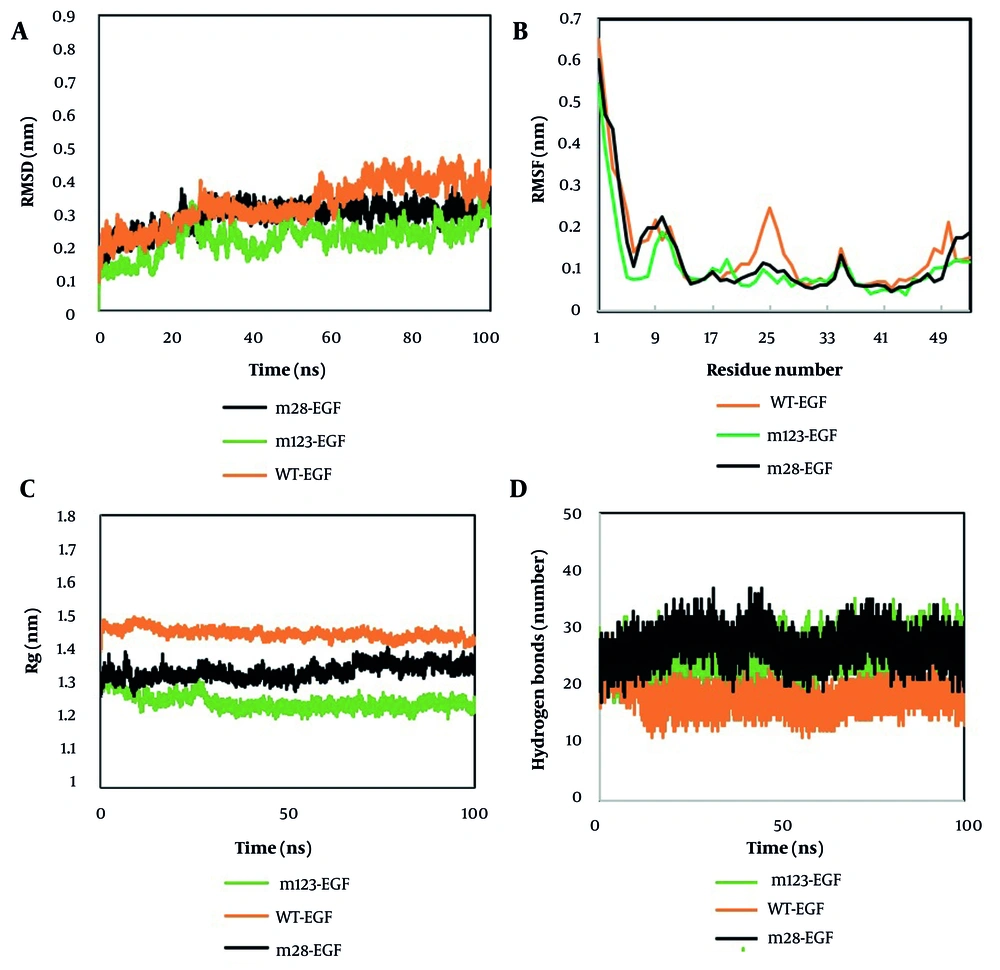

Backbone RMSD analysis during simulations revealed that m28-EGF and m123-EGF mutants had lower average RMSD values (~2.87 Å and ~2.18 Å) compared to wild-type (~3.25 Å), indicating greater structural stability in the mutants (Figure 2A). These mutations significantly influenced the dynamic behavior of the EGF structures.

The RMSF analysis from MD simulations revealed differences in flexibility between wild-type and mutant EGF structures. Both WT and mutant EGFs displayed similar overall fluctuation patterns, with low RMSF values (valleys) at β-sheet regions (residues 19 - 23, 28 - 32, 37 - 38, and 44 - 45) due to stable hydrogen bonding (Figure 2B). Peaks between β-sheets represented flexible loop regions. Wild-type EGF showed higher fluctuations, particularly at residues 21 - 28, compared to mutants. Mutations in m123-EGF (M21R, K28S) and m28-EGF (E24K, L26V, K28R) reduced flexibility and increased structural stability. The average RMSF values were 1.42 Å (wild-type), 1.27 Å (m28-EGF), and 1.06 Å (m123-EGF), confirming that the mutants are more stable than the wild type.

The radius of gyration (Rg) plots showed a consistent decrease in values across simulations, suggesting that the mutations increased structural compactness and stability (Figure 2C). The average Rg values for WT EGF, m28-EGF, and m123-EGF were 1.45 nm, 1.34 nm, and 1.24 nm, respectively. These findings align with the RMSF results, indicating that the mutations reduce flexibility and promote more compact, stable EGF conformations.

Hydrogen bond analysis showed that mutant EGFs formed more hydrogen bonds than the WT. The m28-EGF and m123-EGF exhibited 17 - 37 hydrogen bonds, while WT showed 11 - 29 (Figure 2D). This increase indicates improved structural stability in the mutants. The results are consistent with RMSF and Rg analyses, confirming greater compactness of mutant structures.

4.2. Binding Characterizations of Epidermal Growth Factor Peptides (m123-EGF, m28-EGF, and Wild-Type) to Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor

The study analyzed EGF-EGFR interaction energies to compare binding affinities and identify key interacting residues.

4.2.1. Analysis of Interaction Energy

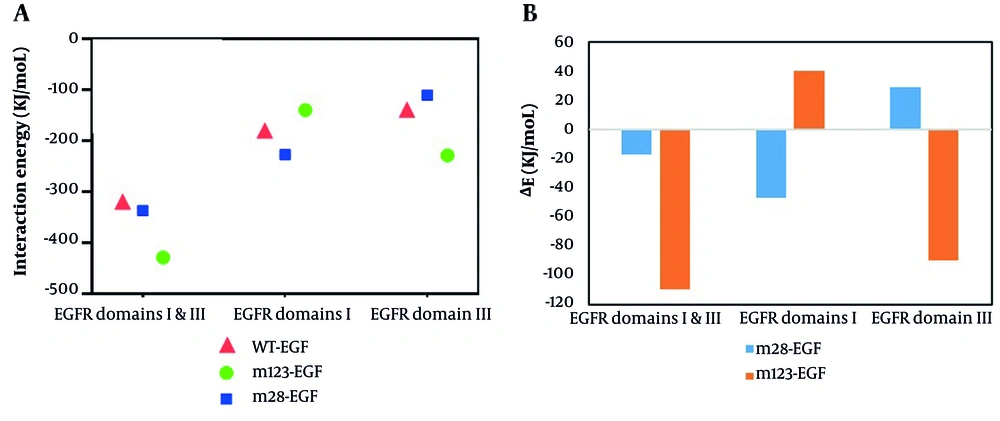

Interaction energy analysis revealed the energetic contributions of individual residues to EGF-EGFR binding (15). Binding occurred at three sites on EGFR domains I and III, with all complexes showing negative binding free energies, indicating favorable interactions (Table 2 and Figure 3). Mutant complexes (m28-EGF/EGFR and m123-EGF/EGFR) exhibited higher interaction energies than the wild type, suggesting enhanced binding affinity. The m28-EGF showed stronger affinity for domain I, while m123-EGF preferred domain III, confirming that the mutations improved ligand–receptor binding stability.

Interaction energy analysis of epidermal growth factor (EGF)-EGFR complexes. A, interaction energies between wild-type and mutant EGFs with EGFR domains I and III calculated using Discovery Studio; B, differences in interaction energies between mutants (m28-EGF, m123-EGF) and wild-type were compared for domains I, III, and combined regions.

| Variables | Van der Waals Energy a | Electrostatic Energy | Interaction Energy |

|---|---|---|---|

| Interaction energy of EGF with domains I & III EGFR | |||

| WT-EGF | -127.98 | -191.36 | -319.35 |

| m28-EGF | -117.60 | -219.21 | -336.81 |

| m123-EGF | -208.30 | -220.45 | -428.75 |

| Interaction energy of EGF with domain I EGFR | |||

| WT-EGF | -62.30 | -117.43 | -179.74 |

| m28-EGF | -61.35 | -165.36 | -226.71 |

| m123-EGF | -58.49 | -80.76 | -139.25 |

| Interaction energy of EGF with domain III EGFR | |||

| WT-EGF | -65.30 | -73.83 | -139.14 |

| m28-EGF | -56.26 | -53.84 | -110.10 |

| m123-EGF | -149.27 | -139.29 | -288.57 |

Abbreviations: EGF, epidermal growth factor receptor; WT-EGF, wild-type EGF; EGFR, Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor

a All of the energies are presented in kJ/mol.

Appendix 4 in Supplementary File summarizes the contribution of mutated residues in m123-EGF and m28-EGF to EGFR binding affinity compared to WT. In m123-EGF, residues R48, G51, and R52 showed stronger interactions with EGFR domain III, particularly due to K48R and L52R mutations, which enhanced overall binding and activity. These results highlight the importance of site III in mediating EGF–EGFR affinity and downstream signaling (26). In m28-EGF, residues K24, V26, and R28 showed increased interaction with EGFR domain I, with T48 also contributing to domain III binding — consistent with reports linking K48T mutation to enhanced EGFR activation (27).

4.2.2. Analysis of Hydrogen Bond, Salt Bridge, and Hydrophobic Interaction

During MDS, stable non-covalent interactions between EGFR and EGF peptides were analyzed by assessing salt bridges and hydrogen bonds. Results (Appendices 5 and 6 in Supplementary File) showed that conserved residues formed salt bridges and hydrogen bonds, including a common short parallel β-sheet formed by EGFR residues 15 - 18 and ligand residues 31 - 33. The total hydrogen bonds at the EGF/EGFR interface were 39 for WT EGF/EGFR, 38 for m28-EGF/EGFR, and 78 for m123-EGF/EGFR complexes, with the highest number in the m123-EGF/EGFR complex involving three mutations (Arg48, Gly51, Arg52) that formed multiple hydrogen bonds at interaction site III. A conserved salt bridge between EGF-Arg41 and EGFR Asp355 was observed in all complexes. A salt bridge between EGFR Glu90 and ligand Lys28 was present in wild-type and m28-EGF but lost in m123-EGF due to the Lys28Ser mutation. Hydrophobic interactions were the main contributors to ligand-receptor binding, with mutant complexes showing increased hydrophobic interactions relative to WT.

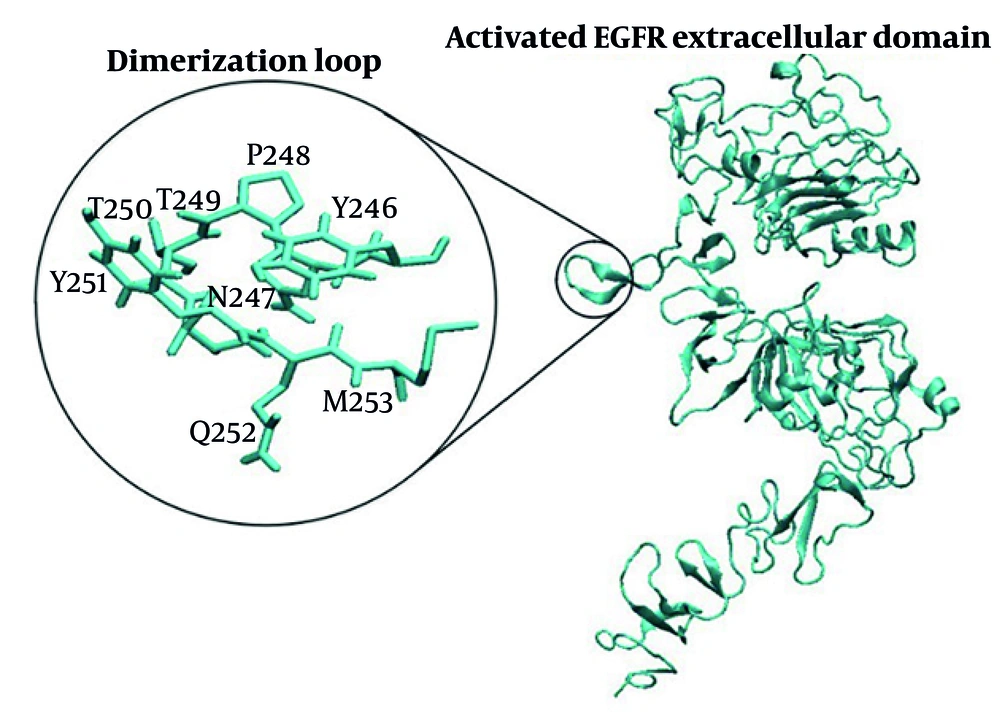

4.3. Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor Dimer Interface

The EGFR ligand binding involves domains I and III, while domains II and IV mediate receptor dimerization. Dimerization mainly occurs through domain II, particularly the dimerization arm (residues 240 - 260) (28). The β-hairpin tip (residues 246 - 253) acts as a “hand” that interacts with the other receptor’s domain II (26, 29) (Figure 4). Mutations in key residues such as Tyr246 or Tyr251 disrupt homodimer formation, highlighting the arm’s critical role.

Molecular dynamics simulation analysis of 2EGF/2EGFR complexes examined how different EGF ligands (WT, m123, m28) affect the EGFR dimerization region, especially domain II. Hydrogen bonds at the EGFR/EGFR interface increased in mutant complexes: Thirty-six (WT), 47 (m123), and 70 (m28). Key residues at the dimerization arm tip (246 - 253) formed 12, 17, and 24 hydrogen bonds with partner chain residues in WT, m123, and m28, respectively. m28-EGF also exhibited the highest number of hydrophobic interactions, further stabilizing the dimer interface.

Table 3 shows that EGFR/EGFR interaction energies are stronger in mutant complexes (-270.23 kcal/mol for m28-EGF and -301.03 kcal/mol for m123-EGF) compared to WT (-245.78 kcal/mol). Interaction energies between domain II of one EGFR and domains I-III of the other also increased in mutants (Table 3). Domain II contributes approximately 90% of the total EGFR dimerization energy. These results highlight the enhanced stability of mutant dimers and provide insights for therapeutic targeting of EGFR dimerization.

| Variables | Van der Waals Energy a | Electrostatic Energy | Interaction Energy |

|---|---|---|---|

| Interaction between domains I-IV of chain A and domains I-IV of chain B of EGFR | |||

| WT-EGF | -152.97 | -92.81 | -245.78 |

| m28-EGF | 134.13 | 136.10 | -270.23 |

| m123-EGF | -151.73 | -149.29 | -301.03 |

| Interaction between domains I-III of chain A and domains I –III of chain B of EGFR | |||

| WT-EGF | -132.54 | -93.64 | -226.18 |

| m28-EGF | -119.94 | -130.12 | -250.06 |

| m123-EGF | -133.01 | -149.26 | -282.27 |

| Interaction between domain II of chain A and domains I-III of chain B of EGFR | |||

| WT-EGF | -127.34 | -95.47 | -222.81 |

| m28-EGF | -109.40 | -128.65 | -238.05 |

| m123-EGF | -130.58 | -146.22 | -276.80 |

| Interaction between residues 570 –614 of domain IV chain A with residues 570 –614 of domain IV chain B of EGFR | |||

| WT-EGF | -20.23 | -0.08 | -20.31 |

| m28-EGF | -16.18 | -3.54 | -19.72 |

| m123-EGF | -16.23 | -2.10 | -18.33 |

Abbreviations: EGF, epidermal growth factor receptor; WT-EGF, wild-type EGF; EGFR, Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor

a All of the energies are presented in kJ/mol.

This study demonstrates that engineered EGF mutants with specific amino acid substitutions can enhance binding affinity, structural stability, and thermodynamic favorability toward EGFR. Mutations such as K28R in m28-EGF and K48R/L52R in m123-EGF increase favorable interactions with EGFR domains I and III, respectively, by promoting salt bridges, hydrophobic contacts, and entropy-driven stabilization. These changes reduce flexibility and generate more compact, stable EGF conformations, highlighting the importance of positively charged and bulky residues at key positions. While these results support the potential of EGF super-agonists for regenerative applications and offer insights for designing EGFR-modulating therapeutics, they also underscore that even minimal structural changes in EGF can produce significant biological effects. Given the strong association between elevated EGFR activity and oncogenic risk, the development and use of hyperactive or tethered EGF variants must be approached with great caution, with thorough evaluation of their long-term safety and signaling outcomes.