1. Background

Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) remains one of the most serious global health threats, infecting over 38 million people worldwide and causing nearly one million deaths annually (1, 2). Its high mutation rate and rapid emergence of drug-resistant strains continue to challenge long-term therapeutic success (3). Among viral targets, HIV-1 protease (HIV-1 PR) is an essential aspartyl homodimer that mediates viral maturation through proteolytic processing of Gag and Gag-Pol polyproteins, making it a validated and indispensable target in combination antiretroviral therapy (4). Consequently, protease inhibitors constitute a central component of combination antiretroviral therapy.

Darunavir (DRV) is among the most clinically successful protease inhibitors, characterized by high affinity for the PR active site, broad activity against resistant variants, and favorable pharmacokinetic properties (5). Nonetheless, the continual emergence of resistance-conferring substitutions and the demand for improved pharmacological profiles motivate continued efforts to dissect the molecular determinants of DRV’s potency and to rationally optimize DRV-like scaffolds.

The catalytic mechanism of HIV-1 PR is inherently dynamic, driven by flexible flap regions that regulate access to the active site and govern both substrate processing and inhibitor binding. These conformational transitions, coupled with solvent rearrangements and backbone fluctuations, critically shape the energetic landscape of ligand recognition (6). Consequently, understanding how structural and stereochemical modifications influence these dynamic processes is key to improving inhibitor design beyond what static crystallographic data can reveal. Medicinal chemistry efforts have repeatedly demonstrated that minimal stereochemical or substituent modifications may leave the static binding pose largely unaltered while producing substantial changes in antiviral potency and resistance profiles. This observation underscores the limitations of single-structure or docking-based analyses and highlights the necessity for dynamical investigations that capture the time-dependent behavior of the protease-inhibitor complex (7-9).

Molecular dynamics (MD) simulations provide atomistic, time-resolved insights into the conformational flexibility, hydration dynamics, and stability of biomolecular complexes under near-physiological conditions (10-13). Unlike static models, MD captures continuous protein and ligand motions, revealing transient interactions and structural fluctuations that govern binding affinity and specificity. In HIV-1 protease systems, MD enables detailed exploration of flap dynamics, elucidating how subtle stereochemical or substituent variations in DRV-like analogs influence conformational behavior and binding energetics, thereby guiding the rational design of more potent and resistance-resilient inhibitors (14, 15).

In this study, four DRV-like compounds were selected from an experimental dataset based on their reported inhibitory constants (Ki), spanning a range of potencies from high to low (16). These molecules, which share a conserved core scaffold but differ in stereochemical configuration and substituent orientation, offer a well-defined system for elucidating how subtle structural modifications modulate protease dynamics and binding energetics. To achieve this, we developed an integrated computational framework combining molecular docking, all-atom MD simulations, and ensemble-based analyses to identify dynamic descriptors that discriminate between high- and low-potency analogs.

2. Objectives

This approach examines how stereochemical variations influence flap mobility, pocket flexibility, and hydrogen-bond persistence, thereby revealing the mechanistic origins of differential binding behavior.

3. Methods

3.1. Receptor and Ligands Preparation

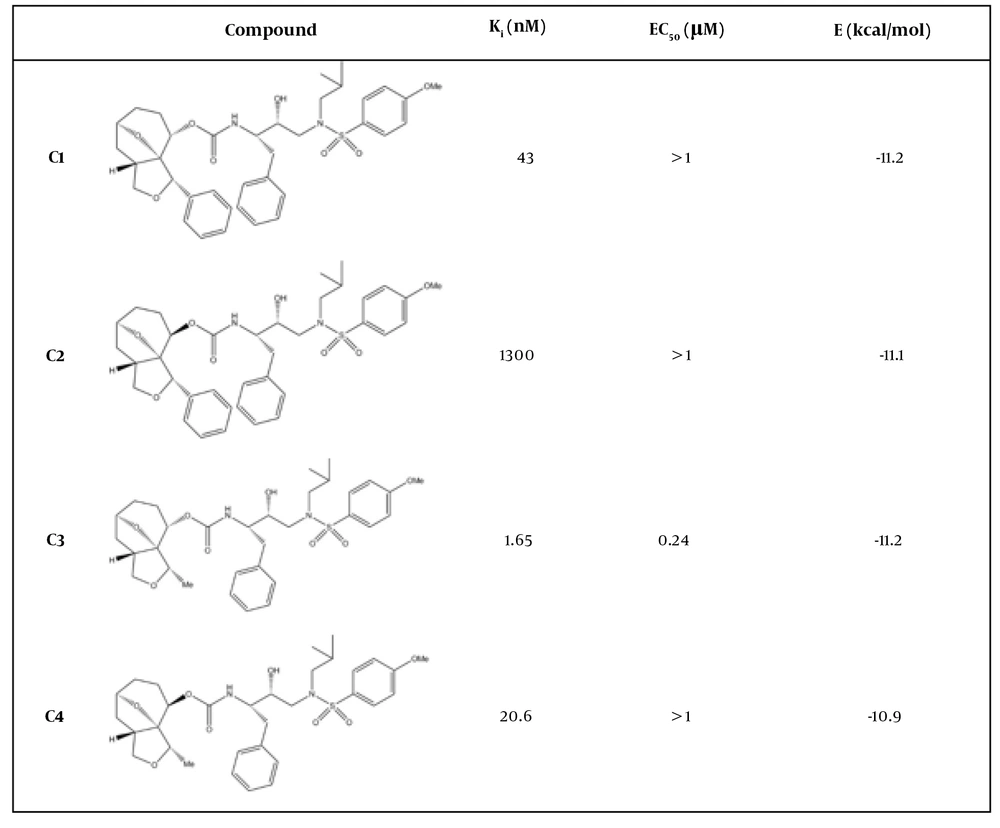

The three-dimensional crystal structure of HIV-1 PR was obtained from the Protein Data Bank (PDB ID: 4HLA), representing the dimeric enzyme in complex with a bound inhibitor. Four ligand systems corresponding to DRV analogs were selected based on previously reported experimental data (Figure 1) (16). The molecular structures of the analogs were reconstructed using ACD/Labs ChemSketch, converted to three-dimensional conformations, and subsequently energy-minimized in Avogadro employing the MMFF94 force field to obtain low-energy geometries suitable for docking. All water molecules and co-crystallized ligands were removed from the receptor structure prior to docking, and missing hydrogen atoms were added to satisfy standard protonation states at physiological pH (17).

3.2. Molecular Docking

Molecular docking was performed to predict the binding orientations and affinities of DRV analogs within HIV-1 PR (18). AutoDock Vina 1.2.5 was used, with receptor preparation carried out in MGLTools, including the addition of Gasteiger charges and merging of nonpolar hydrogens. The search space was defined as a 3 × 3 × 3 nm grid box, centered on the catalytic active site. This grid size was selected to fully capture the binding pocket and to accommodate the conformational flexibility of the DRV analogs. Ligands were treated as fully flexible, allowing rotation of all rotatable bonds, and the exhaustiveness parameter was set to 50. The top-ranked pose for each ligand — based on the lowest predicted binding energy and consistency with known DRV binding — was selected for subsequent MD simulations.

3.3. Molecular Dynamics Simulations

All-atom MD simulations were performed using GROMACS 2023 (19) to assess the conformational stability and dynamic behavior of the apo and ligand-bound HIV-1 PR systems. Protein and ligand topologies were generated using the AMBER99SB-ILDN force field (20) and Antechamber with GAFF parameters (21), respectively. Each system was solvated in a TIP3P water box with counterions added for charge neutrality (22). After energy minimization, equilibration was performed under NVT and NPT ensembles at 310 K and 1 bar using the V-rescale thermostat (23) and Parrinello and Rahman barostat (24), respectively. Production MD simulations were performed for 200 ns using the leap-frog integrator (25). Long-range electrostatic interactions were treated with the Particle Mesh Ewald (PME) method (26), and all bonds involving hydrogen atoms were constrained using the LINCS algorithm (27). Each simulation was repeated three times for reproducibility. Trajectories were analyzed with GROMACS tools, visualized in VMD (28), and LigPlot+ (29) was used to generate 2D ligand–residue interaction maps.

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. Molecular Docking Studies

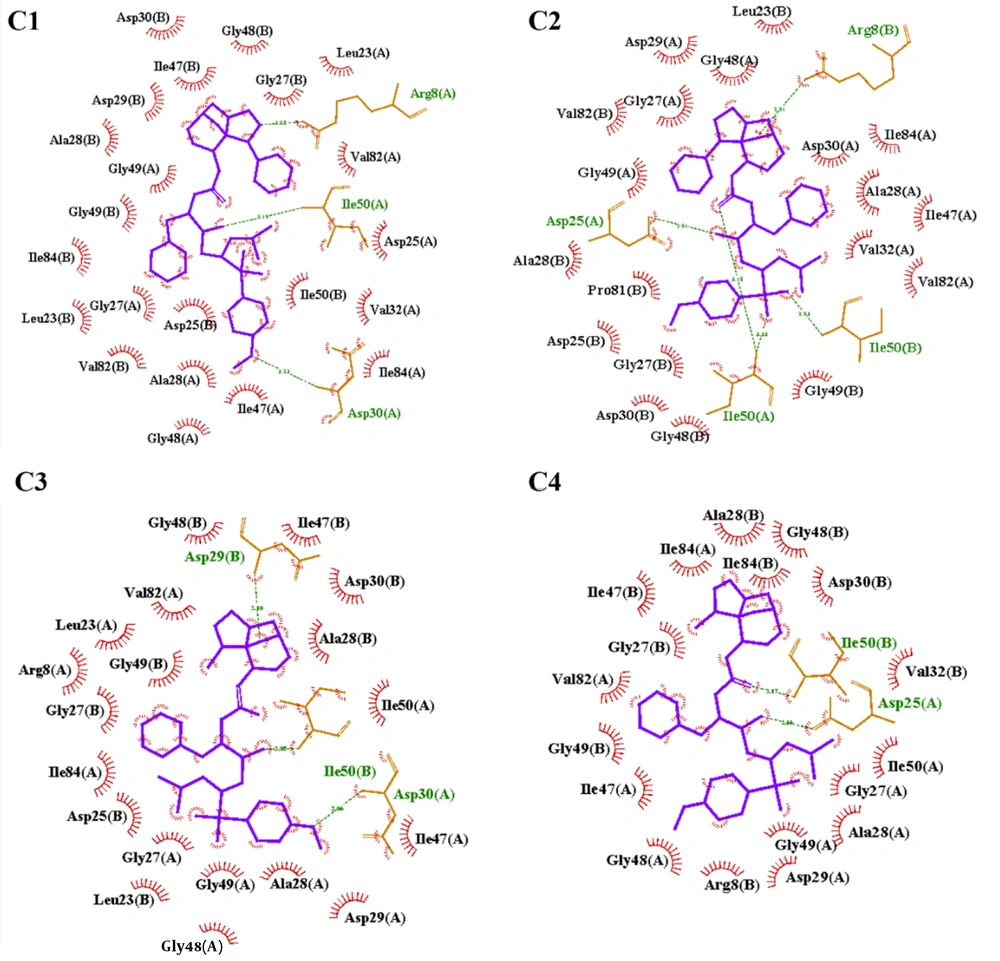

Molecular docking was performed to evaluate the binding orientations and relative affinities of four DRV-like inhibitors within the active site of HIV-1 PR. The results showed that all compounds were accommodated within the active site, forming stabilizing hydrogen bonds and hydrophobic interactions that maintained complex integrity (Figure 2).

The docking results provide an initial structural rationale for inhibitory potency as all of the ligands performed stable, high energetic binding energies with the active site of the enzyme. However, while they capture a general trend, which is not so consistent with the experimental results, static docking cannot account for protein flexibility or solvent effects, highlighting the necessity for subsequent MD simulations to investigate dynamic interactions and conformational adaptations that influence inhibition efficiency.

4.2. Molecular Dynamics Simulations

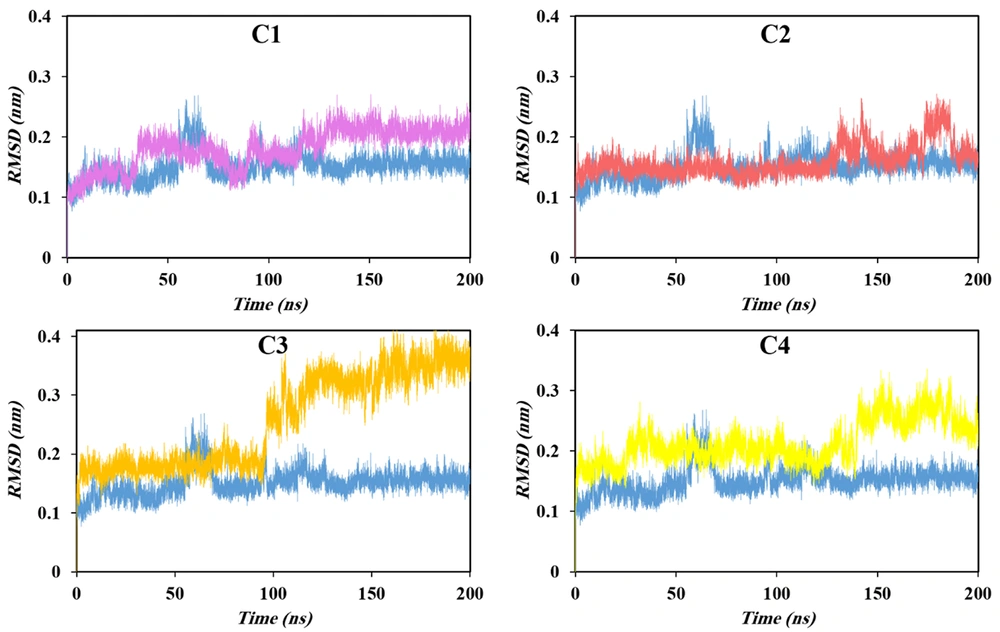

Root mean square deviation (RMSD) serves as a primary quantitative descriptor of structural stability and conformational transitions during MD simulations. By measuring the average displacement of atomic positions relative to an initial reference structure, RMSD provides a robust metric for assessing the equilibration behavior of protein systems and the reliability of subsequent trajectory-based analyses. In well-equilibrated proteins, a plateau in the RMSD trajectory characterized by limited fluctuations indicates that the system has reached a stable dynamic situation (30).

As shown in Figure 3, the apo form of HIV-1 PR exhibited an initial rise in RMSD during the early stages of simulation, corresponding to structural relaxation and optimization of intramolecular interactions. A transient deviation observed near 60 ns likely reflects a minor conformational adjustment associated with local rearrangement of flexible regions, such as the flap domains. Following this phase, the RMSD stabilized at an average value of approximately 0.17 nm, with only marginal fluctuations over the remaining simulation time. This stabilization confirms that the apo system attained dynamic equilibrium beyond 60 ns, validating the use of a 200 ns production trajectory as a representative timescale for further analyses.

Ligand binding introduced distinct perturbations to the protease dynamics, as reflected in the altered RMSD patterns of all complexed systems. Compared with the apo enzyme, ligand-bound complexes required a longer equilibration period and exhibited higher equilibrium RMSD values, suggesting enhanced conformational adaptability upon inhibitor association. These increases in RMSD are indicative of induced fit processes and localized flexibility in response to ligand interactions, consistent with the dynamic nature of HIV-1 PR’s active-site flaps. Notably, a clear positive correlation emerged between the magnitude of RMSD fluctuations and overall mean value with the experimentally reported inhibitory potency of the studied compounds. Complexes formed with more potent inhibitors displayed larger RMSD amplitudes, implying that stronger inhibitors promote greater structural rearrangements within the protease dimer. This observation suggests that induced structural perturbations and transient local instabilities may facilitate conformational trapping of catalytically essential regions, thereby contributing to effective enzyme inhibition. Among all systems, C3, identified as the most potent inhibitor, exhibited the highest RMSD values, underscoring the close interplay between conformational dynamics and inhibitory efficacy.

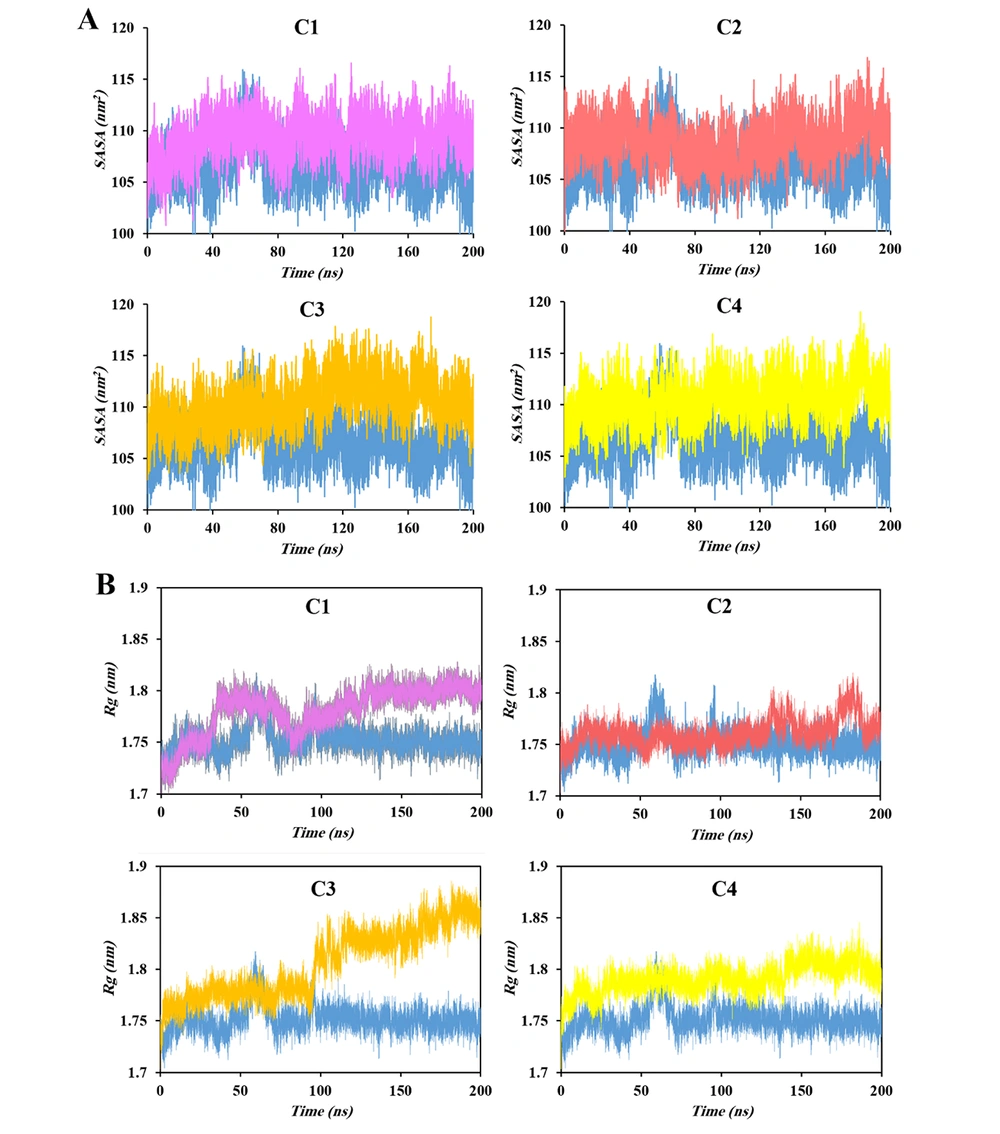

The solvent-accessible surface area (SASA) provides a quantitative measure of protein-solvent interactions and conformational adaptability, reflecting how ligand binding influences surface exposure and hydration dynamics (31). Figure 4A presents the SASA profiles of the HIV-1 PR-inhibitor complexes. Consistent with the observed variations in radius of gyration (Rg), SASA values increased upon ligand binding, reflecting moderate expansion of the protease surface. Among the studied systems, however, C3 exhibited the highest SASA values; no distinct relation between experimental efficacy and the SASA results was observed, indicating less ability of this indicator to be considered as a dynamical descriptor for HIV-1 protease inhibition.

The Rg reflects the overall compactness of a protein, representing the mean distance of atoms from the center of mass of the protein. Increases in Rg indicate structural expansion, whereas decreases correspond to compaction (32). As shown in Figure 4B, all ligand-bound proteases exhibited slightly higher Rg values than the apo form, suggesting partial expansion of the protein structure upon inhibitor binding. This trend correlates with the RMSD results, implying that the observed structural fluctuations arise from ligand-induced relaxation and subtle opening of the protease framework. Such expansion likely results from internal steric pressure exerted by the bound ligands, which may stabilize the active-site region while hindering substrate access and promoting inhibitory efficacy.

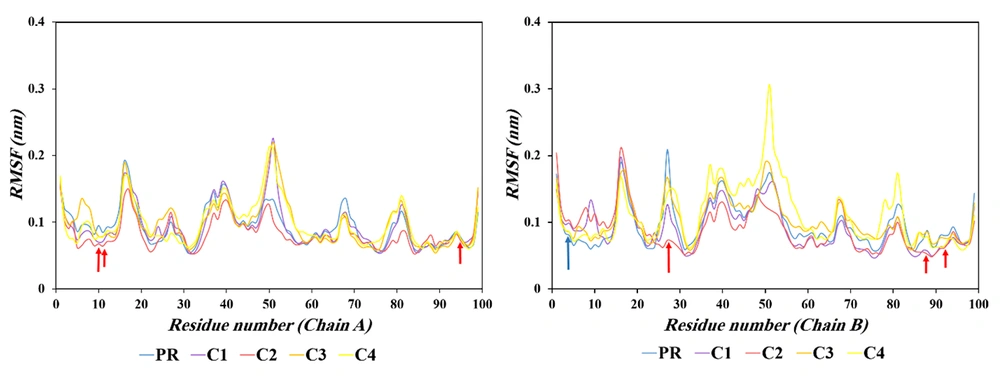

Root mean square fluctuation (RMSF) is a key metric for assessing residue-level flexibility and local dynamic behavior within a protein during MD simulations. This parameter measures the average positional deviation of each atom or residue relative to its mean position over the simulation time. Typically, residues located in flexible regions such as random coils display higher RMSF values, while those within α-helices and β-sheets exhibit lower fluctuations, reflecting their structural rigidity (33, 34).

In this study, variations in RMSF values were analyzed to identify the residues exhibiting enhanced or reduced mobility in the ligand-bound systems compared with the apo protease (Figure 5 and Table 1). The comparative RMSF profiles revealed that, in Chain A, residues Leu10, Val11, and Cys95 showed a gradual decrease in atomic fluctuations ordered from highest to lowest active ligands upon binding, indicating reduced local flexibility caused a reduction in the inhibitory activity. No residues in Chain A exhibited an increasing trend. In contrast, in Chain B, residue Thr4 displayed a consistent enhancement in mobility, with RMSF values rising from 0.0805 Å in the apo form to 0.1031 Å in the C2 inhibitor complex, whereas residues Gly27, Asn88, and Gln92 demonstrated a pronounced and progressive reduction in flexibility across the inhibitor-bound systems.

| Residue | Trend | PR | C1 | C2 | C3 | C4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Leu10 (A) | Decreasing | 0.0949 | 0.0704 | 0.0678 | 0.0794 | 0.0782 |

| Val11 (A) | Decreasing | 0.0845 | 0.0714 | 0.0643 | 0.0789 | 0.0779 |

| Cys95 (A) | Decreasing | 0.0765 | 0.0733 | 0.0717 | 0.0749 | 0.0743 |

| Thr4 (B) | Increasing | 0.0805 | 0.0984 | 0.1031 | 0.0854 | 0.0856 |

| Gly27 (B) | Decreasing | 0.2091 | 0.1266 | 0.0728 | 0.1676 | 0.1429 |

| Asn88 (B) | Decreasing | 0.0876 | 0.0569 | 0.0520 | 0.0856 | 0.0782 |

| Gln92 (B) | Decreasing | 0.0801 | 0.0642 | 0.0616 | 0.0761 | 0.0645 |

The most potent inhibitors, C3 and C4, exhibit an optimal dynamic signature where enhanced flexibility in the β-hairpin (residues Leu10-Val11) and flap domains (residues Gly27, Asn88, Gln92) facilitates an induced-fit mechanism. This conformational adaptability enables optimal hydrophobic packing between the inhibitor and active site, maximizing van der Waals contacts and binding affinity. Concurrently, reduced flexibility at residue Thr4 stabilizes the N-terminal β-sheet critical for dimer integrity. This dual dynamic modulation — promoting functional flexibility in substrate-recognition regions while enforcing structural rigidity at the dimer interface — creates an ideal environment for high-affinity inhibition. The most effective inhibitors thus achieve superior potency not merely through static binding, but by optimally tuning the protein's dynamic landscape to enhance both complementary binding and structural stability.

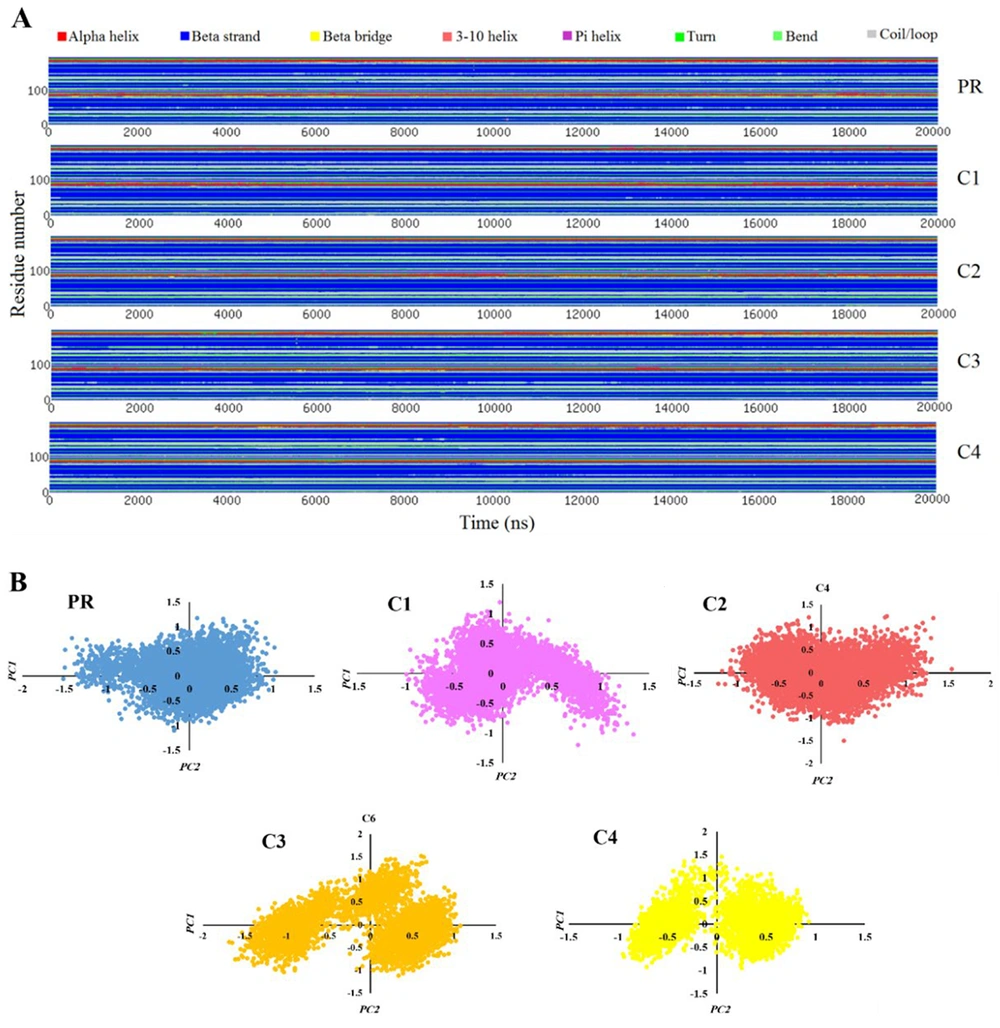

Ligand binding often induces subtle yet functionally significant alterations in a protein’s secondary structure, influencing its conformational stability, flexibility, and catalytic efficiency. The distribution and persistence of α-helices, β-sheets, and loop regions are inherently determined by the amino acid sequence but are dynamically modulated by the physicochemical environment and intermolecular interactions. Structural perturbations resulting from ligand association may therefore reflect the intrinsic adaptability of the protein and provide mechanistic insights into the relationship between flexibility and inhibitory efficacy (35).

In this study, temporal changes in the secondary structural elements of HIV-1 PR were quantified using the define secondary structure of proteins (DSSP) algorithm (Figure 6A). The analysis monitored residue-specific transitions among different structural conformations, enabling correlation of these rearrangements with the experimentally reported inhibitory potencies of the bound ligands. The residues Thr4 and Leu5 are located at the N-terminal interface connecting the two protease monomers. Their presence in well-organized secondary structures such as β-sheets promotes favorable inter-chain interactions that contribute to maintaining the structural integrity of the enzyme. This can further help to stabilize the ligand in the active site as discussed in the previous section. Similarly, Glu34 exhibits a transition from a β-sheet to a loop structure, which disrupts the local β-sheet arrangement and thereby decreases structural stability, leading to the lower stability of the ligands in lower activity compounds.

The hydrophobic loop composed of Ile50, Gly51, Gly52, and Phe53 plays a crucial role in mediating inter-monomer interactions through hydrophobic contacts. The incorporation of Gly49 into the adjacent β-sheet decreases the flexibility of this loop, thereby weakening hydrophobic interactions and ultimately contributing to complex destabilization, which is again seen in the C2 compound as the lowest inhibitory constant. Furthermore, Thr91 and Glu92 are located at the C-terminal α-helix region connecting to the terminal β-sheet that links the two monomers. Their transition into turn conformations reduces local flexibility and weakens hydrogen bonding interactions, leading to partial destabilization of the dimeric structure. This can ultimately lead to destabilizing the ligand in the binding pocket and decreasing its inhibitory efficacy, which is fully in agreement with the results in RMSF analysis. These findings underscore the structural plasticity of HIV-1 PR and highlight the role of secondary structure remodeling as a dynamic determinant of inhibitor recognition. The observed correlations between ligand-induced conformational rearrangements and experimental inhibitory trends suggest that secondary structure dynamics can serve as an informative molecular descriptor for predicting the inhibitory potential of structurally related analogs.

Principal component analysis (PCA) is a computational technique used to identify the most significant components underlying a complex phenomenon from a large dataset. In the context of MD simulations, where proteins consist of a vast number of atoms each moving in multiple directions, PCA provides an efficient approach to analyze the principal modes of protein motion. By projecting the conformational states of the protein onto the pair of principal components corresponding to the highest eigenvalues, each conformation is represented as a point in a two-dimensional space (35). Collectively, all simulation frames form clusters of points that reflect predominant motion patterns. Changes in the primary dynamic directions of the protein are manifested as shifts in the location, distribution, and density of these clusters, indicating alterations in protein dynamics.

Figure 6B reveals distinct differences between the apo protein and the protein complexed with various ligands. For apo protein, the motion is confined to a limited range, resulting in a single, compact cluster. Upon ligand binding, particularly with more potent inhibitors (C3 and C4), both the spatial range and density of points within the clusters increased, reflecting a significant modulation of the protein’s dynamics relative to its free state. Notably, given the observed correlation between cluster dispersion and inhibitory efficacy, these molecular motion clusters can serve as robust dynamic descriptors for predicting the activity of novel compounds.

Given the critical role of protein residues in maintaining structural integrity and functional activity, the temporal pattern of ligand-residue interactions can serve as an informative parameter for assessing the inhibitory potential of compounds. To investigate these interactions, LigPlot+ software was employed to analyze intermolecular contacts between each ligand and the protein over the course of the simulation. The results of this analysis related to 10 various simulation frames are presented in Table 2, illustrating the shared interacting residues across all the frames.

| Ligand | Conserved Core Residues | Core Size |

|---|---|---|

| C1 | Arg8(B), Gly49(A), Thr80(B), Val82(B), Ile54(B) | 5 |

| C2 | Ala28(B), Asp29(A), Asp30(B), Ile47(A), Ile50(B) | 5 |

| C3 | Ile47(A), Asp29(A), Ile50(B) | 3 |

| C4 | Ile47(A), Gly48(A), Ile50(A), Arg8(B), Ile47(B), Gly48(B), Gly49(B), Phe53(B), Ile54(B) | 9 |

Experimental evaluation of four DRV-like HIV-1 protease inhibitors revealed a potency order of C3 > C4 > C1 > C2. Analysis of conserved interaction cores from MD simulations elucidated the structural basis for this hierarchy. The most potent inhibitor, C3, formed a minimal yet optimal core with Ile47(A), Asp29(A), and Ile50(B), creating an efficient hydrophobic clamp and a critical hydrogen bond with a catalytic aspartate. C4, while highly effective, engaged a broader, nine-residue core involving flexible glycines, suggesting a slightly less efficient binding entropy. C1 inhibited via a distinct, secondary site (Arg8, Thr80), which was less critical for function. The weakest inhibitor, C2, bound the primary site but its core contained both Asp29 and Asp30, potentially introducing electrostatic strain and reducing binding affinity. This demonstrates that superior inhibitory power is derived not from the number of interactions, but from the optimized, strain-free engagement of key hydrophobic and catalytic residues, a principle masterfully executed by C3.

5. Conclusions

This study has integrated molecular docking with extensive MD simulations to establish a comprehensive dynamic profile of DRV-like HIV-1 protease inhibitors, revealing that inhibitory potency emerges from the complex interplay between specific ligand-residue interactions and ligand-induced modulation of protein dynamics. Analysis of global parameters revealed that potent inhibitors induced subtle increases in RMSD, Rg, and SASA values, reflecting enhanced conformational sampling rather than destabilization. Crucially, residue fluctuation analysis demonstrated that effective inhibitors enhance flexibility in flap and β-hairpin regions (residues 10 - 11, 27, 88, 99) to facilitate optimal hydrophobic packing through induced-fit mechanisms, while enforcing rigidity at the dimer interface (residue 4) to stabilize the ligand-bonded protease homodimer. Define secondary structure of proteins analysis further documented ligand-dependent secondary structure transitions in regions critical for monomer communication and flap dynamics, while PCA revealed that potent ligands broaden the conformational landscape by stabilizing inhibitory sub-states. Most importantly, interaction analysis confirmed that superior potency stems from a minimalist, high-efficiency interaction core exemplified by the optimal engagement of Ile47(A), Asp29(A), and Ile50(B), which combines a robust hydrophobic clamp with a critical hydrogen bond to the catalytic apparatus. These multi-faceted findings provide a refined framework for rational inhibitor design, advocating for compounds that precisely optimize the dynamic landscape by promoting functional flexibility in substrate-recognition regions while securing quaternary structural stability.