1. Background

Congenital anomalies (CAs) are a global health priority due to their significant impact on infant survival and long-term health (1). Defined as structural or functional abnormalities present at birth, CAs can be detected prenatally, at delivery, or postnatally (2). Globally, they affect 2 - 3% of live births, equating to approximately 1 in 33 infants (3). The CAs contribute to 21% of neonatal deaths and rank as the fifth leading cause of reduced life expectancy before age 65, in addition to being a major source of disability (4). The prevalence of CAs varies widely across regions. Studies indicate that the Middle East and North Africa have the highest rates, ranging from 82 per 1,000 live births in Sudan to 39.7 per 1,000 in France (5). In Iran, recent data suggest a prevalence of 24.9 per 1,000 live births (6). Disparities also exist between low-income (64.2 per 1,000), developing (55.7 per 1,000), and developed nations (47.2 per 1,000) (5). Multiple factors contribute to CAs, including genetic disorders, nutritional deficiencies, TORCHES infections, alcohol consumption, environmental pollutants (e.g., pesticides), tobacco use, sexually transmitted infections, and advanced maternal age (≥ 35 years) (7). Genetic factors, such as single-gene defects (6% - 7%) and chromosomal abnormalities (6% - 7%), along with gene-environment interactions (20% - 25%) and teratogen exposure (6% - 7%), play significant roles. However, nearly 50% of CAs have no identifiable cause (7). The CAs are categorized as major or minor — major anomalies are life-threatening or impair function, whereas minor anomalies are primarily cosmetic with minimal health impact (8). Managing CAs involves substantial financial and social burdens, with treatment and rehabilitation often yielding suboptimal outcomes (9). Some severe anomalies lead to miscarriage or stillbirth, underscoring the importance of prevention over costly interventions (10). Identifying and mitigating risk factors can reduce the personal, economic, and societal consequences of CAs (10). Despite the high costs associated with CAs (11), reliable local prevalence data are scarce, particularly in Birjand. Regional variations mean that findings from other countries — or even other Iranian cities — cannot be generalized.

2. Objectives

Therefore, the present study aimed to assess the prevalence of major CAs among live births in Birjand to inform public health strategies.

3. Methods

3.1. Design Study

This cross-sectional descriptive study examined all live births in Birjand’s maternity hospitals (Vali-Asr, Shahid Rahimi, Milad, and Army hospitals) from January 2018 to December 2022. The inclusion criteria comprised live-born infants, while stillbirths and neonates who died immediately after birth (due to the need for autopsy for CAs diagnosis) were excluded.

3.2. Participants

Neonatologists and pediatricians conducted thorough physical examinations on the first day of birth.

3.3. Scales

Suspected cases underwent further diagnostic tests, including echocardiography, ultrasonography, and CT scans, leading to the identification of 65 infants with CAs. Census sampling was employed for data collection.

3.4. Data Collection

Data on live births were extracted from the Iman portal (www.iman.health.gov.ir), while hospital medical records provided details on infants with major anomalies. A researcher-designed checklist captured maternal age, infant sex, gestational age, birth season/year, residence, and nationality for both healthy and affected infants. In total, 45,281 live births were analyzed.

3.5. Data Analysis

Anomalies were classified according to the European Surveillance of Congenital Anomalies (EUROCAT) guidelines. Descriptive statistics (frequency, percentage, mean, standard deviation) and analytical tests (chi-square) were used to assess associations between major anomalies and maternal/infant characteristics (age, sex, gestation, birth season, residence, nationality). Data analysis was performed using SPSS version 22, with a significance level set at P < 0.05.

3.6. Ethical Consideration

All patient information remained confidential and the results were presented in general terms. It should be noted that this study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Birjand University of Medical Sciences with the ethics code IR.BUMS.REC.1400.397.

4. Results

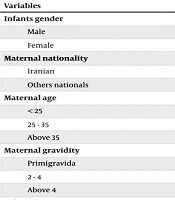

During the five-year study period, there were a total of 45,281 live births in Birjand city, with 65 cases afflicted by major CAs. Of these births, 23,452 (51.79%) were male and 21,829 (48.21%) were female. The majority of mothers (54.86%) were aged between 25 and 35 years. Approximately 85.8% of the mothers resided in urban areas, and the vast majority (98.38%) were of Iranian nationality. Additional information related to live births is provided in Table 1.

| Systems and CAs | No. (%) |

|---|---|

| Nervous system | |

| Hydrocephalus | 3 (4.1) |

| Microcephaly | 5 (6.8) |

| Spina bifida/meningocele | 7 (9.5) |

| Cardiovascular system | |

| TOF | 5 (6.8) |

| TGA | 3 (4.1) |

| Truncus arteriosus | 2 (2.7) |

| AVSD | 3 (4.1) |

| TAPVC | 1 (1.4) |

| HLHS | 1 (1.4) |

| DILV | 1 (1.4) |

| Pulmonary atresia | 2 (2.7) |

| Digestive system | |

| Esophageal atresia | 5 (6.8) |

| Anorectal malformation | 4 (5.4) |

| Agenesis, atresia or congenital stenosis of the small intestine | 3 (4.1) |

| TEF | 2 (2.7) |

| Duodenal atresia | 2 (2.7) |

| Eye | |

| Congenital glaucoma | 2 (2.7) |

| Urinary/genital | |

| Ureteropelvic junction obstruction | 1 (1.4) |

| Hydronephrosis | 1 (1.4) |

| PKD | 1 (1.4) |

| VUR | 1 (1.4) |

| Abdominal wall | |

| Omphalocele | 3 (4.1) |

| Limb/skeletal | |

| Achondroplasia | 5 (6.8) |

| Diaphragmatic hernia | 7 (9.5) |

| Pulmonary | |

| Hypoplasia and dysplasia | 2 (2.7) |

| Situs inversus | 2 (2.7) |

Abbreviations: CAs, congenital anomalies; TOF, tetralogy of fallot; TGA, transposition of great arteries; TAPVC, total anomalous pulmonary venous connection; AVSD, atrioventricular septal defect; HLHS, hypoplastic left heart syndrome; TEF, tracheoesophageal fistula; PKD, polycystic kidney disease; VUR, vesicoureteral reflux; DILV, double inlet left ventricle.

Among the 65 infants with major anomalies, 38 (58.5%) were male and 27 (41.5%) were female. Most mothers of children with major anomalies (63%) were aged between 25 and 35 years, and 61.5% lived in urban areas. Additionally, 96.9% of these mothers were of Iranian nationality. Further demographic information related to major anomalies is detailed in Table 1.

According to the Iman system, the total number of live births was approximately 45,281, with 65 infants having major anomalies, resulting in a prevalence of 14.3 per 10,000 live births. The most frequent anomalies were related to the cardiovascular system (18 cases), digestive system (16 cases), and central nervous system (15 cases).

The chi-square test was used to examine the relationship between demographic variables and major abnormalities. The results indicated no statistically significant relationship between the occurrence of major abnormalities and the infants’ gender (P = 0.28), maternal nationality (P = 0.35), maternal age (P = 0.39), maternal gestation (P = 0.08), or infants’ birth season (P = 0.09). However, there was a statistically significant relationship between the maternal place of residence and the occurrence of major abnormalities (P < 0.001), with a higher prevalence of major abnormalities in mothers living in rural areas (0.38%) compared to those in urban areas (0.10%) (Table 2).

| Variables | Newborn Without CAs (N = 45216) | Newborn with CAs (N = 65) | Total (N = 45281) | P-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Infants gender | 0.282 | |||

| Male | 23414 (51.7) | 38 (58.5) | 23452 (51.8) | |

| Female | 21802 (48.3) | 27 (41.5) | 21829 (48.2) | |

| Maternal nationality | 0.351 | |||

| Iranian | 44485 (98.3) | 63 (96.9) | 44548 (98.3) | |

| Others nationals | 731 (1.7) | 2 (3.1) | 733 (1.7) | |

| Maternal age | 0.399 | |||

| < 25 | 9919 (21.9) | 11 (16.9) | 9930 (21.9) | |

| 25 - 35 | 24799 (54.8) | 41 (63) | 24841 (54.8) | |

| Above 35 | 10498 (23.3) | 13 (20.1) | 10510 (23.3) | |

| Maternal gravidity | 0.087 | |||

| Primigravida | 10992 (24.3) | 13 (20) | 11005 (24.3) | |

| 2 - 4 | 30664 (67.8) | 51 (78.5) | 30715 (67.8) | |

| Above 4 | 3560 (7.9) | 1 (1.5) | 3561 (7.9) | |

| Infants birth season | 0.092 | |||

| Spring | 11518 (25.4) | 13 (20) | 11531 (25.4) | |

| Summer | 11886 (26.2) | 26 (40) | 11912 (26.4) | |

| Autumn | 10880 (24) | 12 (18.5) | 10892 (23.9) | |

| Winter | 10932 (24.4) | 14 (21.5) | 10946 (24.3) | |

| Maternal place of residence | < 0.001 | |||

| Urban | 38814 (85.8) | 40 (61.5) | 38854 (85.8) | |

| Rural | 6402 (14.2) | 25 (38.5) | 6427 (14.2) |

Abbreviation: CAs, congenital anomalies.

a Values are expressed as No. (%).

5. Discussion

This study identified 65 cases of major CAs among 45,281 live births (14.3 per 10,000) in Birjand from 2018 to 2022, revealing a significantly lower prevalence than regional and global reports. Sedighi et al. (12) documented a prevalence of 85 per 10,000 in Hamadan, while Vatankhah et al.’s (4) systematic review reported Iran’s national rate at 23 per 10,000. Notably, Birjand’s CAs prevalence decreased from Faal et al.’s (10) 2015 - 2016 estimate of 18.3 per 10,000, suggesting potential improvements in prenatal care or methodological differences. Globally, CAs rates vary substantially, from 170 per 10,000 in Nigeria (13) to 132 per 10,000 in Qatar (8) and 63.8 per 10,000 in Guatemala (14), reflecting disparities in genetics, environment, and healthcare access.

Cardiovascular (18 cases), gastrointestinal (16 cases), and nervous system anomalies (15 cases) predominated, with spina bifida/meningocele and diaphragmatic hernia (7 cases each) being the most frequent. This aligns with Vietnamese data highlighting cardiac and digestive anomalies (15) but contrasts with Ethiopian studies emphasizing neural tube defects (16). The persistent prevalence of neural tube anomalies — despite known benefits of folic acid prophylaxis (17, 18) — suggests gaps in prenatal education or supplementation adherence. The high frequency of cardiovascular anomalies corroborates Toobaie et al.’s (19) findings in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs), with risk factors including maternal diabetes, consanguinity, and teratogen exposure (20-22).

No significant associations emerged between CAs and infant sex, maternal age, gestational age, birth season, or nationality. While consistent with Ajao and Adeoye’s (23) Nigerian study, this contrasts with gender-discrepant reports: Narapureddy et al. (11) found higher female CAs rates, whereas Sokal et al. (24) noted male predominance. Maternal age showed no correlation, contradicting established links to advanced maternal age (25-27); this may reflect our study’s uneven age distribution. Parity and gestational age similarly lacked significance, aligning with Nigerian and Qatari studies (8, 23, 28, 29) but opposing Sarkar et al.’s (30) Indian multiparity association. Limited evidence on birth season effects (31, 32) warrants contemporary research.

Rural residence significantly predicted higher CAs prevalence (0.38% vs. 0.10% urban), echoing Riyahifar et al.’s (33) Iranian findings but conflicting with null-association studies (7, 12) and an African meta-analysis showing lower rural risk (34). This disparity may reflect rural healthcare access barriers or environmental exposures, emphasizing the need for targeted interventions.

5.1. Conclusions

This study showed that the prevalence of CAs among live births in Birjand was 14.3 cases per 10,000 live births, which is lower than the rates reported in other regions of Iran. The high prevalence of cardiovascular, gastrointestinal, and central nervous system anomalies highlights the need to focus on identifying and managing risk factors for CAs, as well as providing more comprehensive prenatal care services.

5.2. Study Limitations

A limitation of this study stems from its reliance on the National Iman System, which only captures CAs diagnosed at birth. This approach likely underestimates the true prevalence, as it misses: (1) Anomalies detected later in infancy; and (2) cases terminated before 18 weeks and 5 days under Iran’s pregnancy termination policies. Additional constraints include the short study duration and limited geographical coverage, which may affect generalizability. Future research should incorporate longer follow-up periods, wider regional representation, and prenatal diagnosis data to provide more accurate epidemiological estimates.