1. Introduction

Cerebral palsy (CP) is a neuromotor disorder that affects growth, movement, muscle tone, and posture (1). Children with this condition experience a wide range of secondary disorders throughout their lives, including sensory, perceptual, cognitive, communication, and behavioral disorders, which differentially affect their functional abilities (2). The prevalence of CP varies from 1.5 to 3 per 1,000 live births (3). Although factors such as prematurity and low birth weight are major risk factors for CP (4), numerous epidemiological studies have reported that half of the children with CP are born without any identifiable risk factors (5). The most common causes of post-neonatal CP are reported to be traumatic brain injuries, drowning, and meningitis (2). These children face significant limitations in daily living activities such as eating, dressing, bathing, and mobility. These limitations create a continuous need for special and long-term care (6).

Caring for a child is the responsibility of parents, but this role creates a great deal of pressure for the primary caregiver, mainly mothers, when the child has functional limitations and long-term dependency (7). Thus, the child's disability not only affects the child's life but also has a profound impact on the quality of life of caregivers (8). In this regard, one of the important duties of nurses is to identify the needs of the child and family and to provide interventions to meet them in a timely, quality, and appropriate manner (9).

Patient comfort is a basic need that can significantly affect function, quality of life, and outcomes of care. Providing patient comfort is considered an integral part of nursing and the art of nursing (7). Katherine Kolcaba, a well-known nurse and theorist, was born in Cleveland, Ohio, in 1965 and developed the comfort theory after her studies. Kolcaba's comfort theory was introduced in the 1990s and is still used in healthcare today. The theory is constantly evolving, with the latest update in 2007 (7, 9).

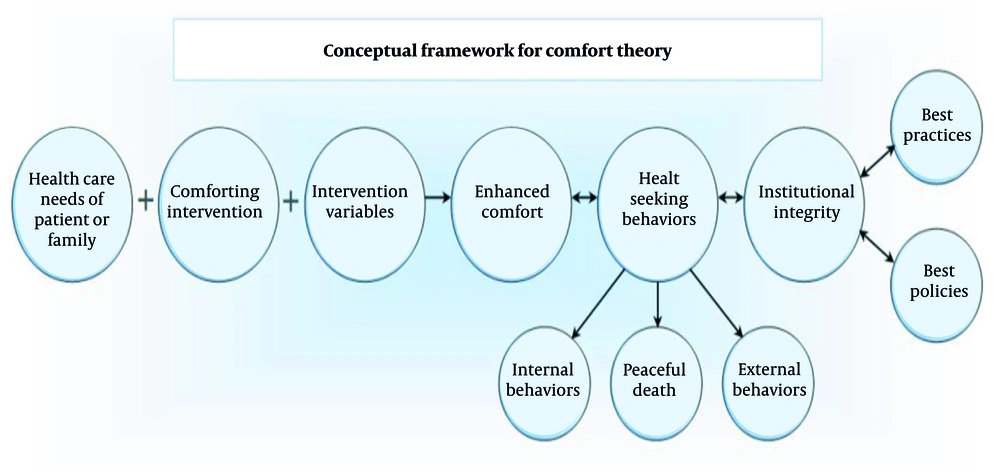

Kolcaba defines nursing as the process of assessing the patient's comfort needs, developing and implementing appropriate nursing interventions, and evaluating the patient's comfort status throughout the nursing interventions. She believes that the ultimate goal of this process is to increase patient comfort. Enhanced comfort is a positive, affirmative, and desired health outcome (10). Kolcaba describes three forms of comfort: Relief, ease, and transcendence. Kolcaba examines these three states of comfort in four contexts: Physical, psychological, social-cultural, and environmental (Figure 1) (8).

An important duty of nurses is to identify the needs of children and their parents and meet them in a desirable, high-quality, and timely manner. Using nursing theories can help nurses in this direction (11). The application of this theory to children with CP has rarely been reported in Iran. Therefore, this study aimed to apply Kolcaba's comfort theory in the care of a child with CP admitted to Ali Ibn Abi Talib Hospital in Rafsanjan.

2. Case Presentation

The patient was a 26-month-old boy, admitted with a diagnosis of CP and seizures. In assessing his growth and development, the child's weight was 7200 g, and his height was 69 cm. He lives with his parents and one older brother, aged 9 years. The father has a high school diploma and runs a private business; the mother holds a bachelor's degree and is a housekeeper. According to the mother's statements, the family's economic status is good. The mother is the child's primary caregiver, and the father is present during visiting hours. The child does not receive support from health institutions such as welfare organizations but is dependent on his family for physical and psychological needs due to his disabilities.

Initial data was obtained through a complete medical history from the child's mother and father, his medical records, and his physical examination. The child was admitted due to fever, cough, shortness of breath, and decreased level of consciousness. The child's vital signs upon admission were: T = 39°C (normal: 36.5 - 37.5°C), PR = 150 bpm (normal for age: 80 - 130 bpm), RR = 55 breaths/min (normal: 20 - 40), SpO2 = 92% (normal: > 95%). During the first day of hospitalization, the child experienced three seizures, for which he received diazepam. He also received oxygen therapy for two days. A summary of key diagnoses, treatments, and comfort interventions from birth to current admission was provided (Table 1).

| Age | Event/Diagnosis | Treatment/Intervention | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Birth | Full-term birth | - | No complications reported |

| 2 wk | Megacolon diagnosed | Colostomy | Temporary, due to inability to pass stool |

| 3 mo | - | Colostomy closed | After weight gain |

| 1 mo | High blood ammonia | Diagnosed with CP | Based on lab tests |

| 6 mo | Developmental dysplasia of the hip | Surgery performed | Failure to treat foot deformity |

| 12 - 24 mo | Developmental regression | - | Previously able to say “mommy”, “daddy” |

| 26 mo (current) | Hospital admission: Fever, cough, and ↓ consciousness | Seizure management (diazepam), O2 therapy, feeding via NGT, and medications for seizure and ammonia control | Multiple seizures, on 1st day of admission |

| 26 mo (current) | Comfort assessment via Kolcaba’s tools | Nursing care based on comfort theory | Pre-intervention comfort score = 2 |

Abbreviation: CP, cerebral palsy.

The child's physical examination on the eighth day is as follows:

- Neurological: Opens eyes; cries and moans; makes unintelligible vocalizations; limbs have spasms. The head is normocephalic and symmetrical; there are no visible bumps or lesions.

- Chest: No cyanosis was observed in the limbs or lips. Respiratory status: SpO2 = 95% without oxygen therapy. Due to low BMI, the ribs were clearly visible in the chest area. There were no chest retractions or respiratory distress. Lung sounds were normal. Peripheral pulses were symmetrical in all four limbs, and the child's heart rate was 102 bpm.

- Skin color and body temperature: The limbs were pale, and capillary refill time was less than 2 seconds. The abdomen was soft and non-tender. The skin was warm to the touch, and no lesions, discoloration, or cyanosis were present on any part of the skin (T: 37.1°C). No bedsores were observed in the skin integrity assessment.

- Eyes: Eyes were normal and symmetrical in shape and anatomical position. Pupils were symmetrical and reacted briskly to light. No tearing or inflammation was present in the conjunctiva.

- Neck: The trachea was midline, and no deviation, asymmetry, masses, or palpable or visible growths were present in any part of the neck. The thyroid gland was palpated, and no enlargement or nodules were felt. Limitation in neck movements was observed due to the presence of a central venous catheter.

- Lymph nodes: Lymph nodes in areas such as the neck, back of the head, front of the ear, collarbone, and groin were examined, and no lymphadenopathy was present.

- Initial laboratory tests: WBC = 11,100; RBC = 4.86; HB = 11.8; Plt = 534,000; ESR = 6; BUN = 49; Cr = 0.9; NA = 142; CRP = +.

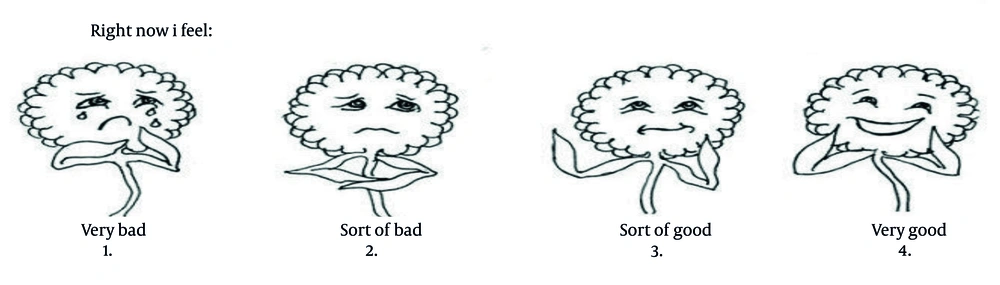

To collect data, informed consent was first obtained from the child's parents. In addition to taking a medical history and performing a physical examination, the comfort daisies tool and Kolcaba's taxonomy were used for qualitative and quantitative data collection. The Comfort Daisies tool ranges from 1 (very poor comfort), 2 (sort of bad), 3 (sort of good), and 4 (very good). This scale has good validity and reliability and can be used as a suitable tool for managing hospitalized children with low levels of consciousness and lack of verbal communication (14, 15). Based on comfort needs (Table 2), nursing diagnoses were made, goals were determined, and interventions were planned, implemented, and evaluated (Table 3).

| Experiential Context | Relief | Ease | Transcendence |

|---|---|---|---|

| Physical | Fever; cough; shortness of breath; immobility; muscle spasms | Administration of antipyretic and anticonvulsant medication; tepid sponging; steam inhalation and oxygen therapy as needed; respiratory and limb physiotherapy | Absence of fever and seizures; SpO2: 95 - 100%; muscle relaxation |

| Psychological | Maternal denial of the child's illness; maternal anxiety and fear of child's gavage feeding | Education of mother on gavage and lavage; education on proper positioning during feeding; modification of attitudes and beliefs | Increased family understanding of the illness for acceptance; parental self-efficacy in child feeding; improved maternal quality of life; reduced parental stress and improved coping |

| Social-cultural | Social isolation; role limitations due to emotional problems | Assistance from other family members in caregiving; referral for social support | Assistance from other family members in child care; peer and parent communication network |

| Environmental | Ambient noise | Reduction of ambient noise; transfer the child to a quiet room | Adequate sleep |

| Variables | Assessment | Goal | Intervention | Evaluation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Relief | ||||

| Physical | Cough; fever; shortness of breath; seizures; skin rash due to immobility | Absence of cough, fever, seizures, shortness of breath; absence of skin breakdown | Antipyretic administration; limb and chest physiotherapy, change position; tepid sponging for fever reduction; adequate fluid intake via iv and oral routes; oxygen therapy | T = 37.2°C; absence of seizures; absence of cough; absence of observed bedsores; SpO2: 95 - 100% |

| Psychological | Maternal denial of child's illness; maternal anxiety and fear | Reduction of maternal anxiety; family acceptance of the illness | Providing information to the family about the nature of the illness | Acceptance of the seizure diagnosis; maternal self-efficacy in caring for her child |

| Social-cultural | Social isolation | Ability to seek help from others | Educating other family members in care and supporting the mother; guidance on utilizing support systems | Presence of other family members and assistance to the mother in care |

| Environmental | Ambient noise | Reduction of ambient noise | Reducing noise in the pediatric ward and transfer to a quiet room | Quiet environment |

| Ease | ||||

| Social-cultural | Social isolation | Ability to manage the child and family's condition; ability to request support from others | Education on meeting own and family's needs; guidance on support systems | Increased maternal empowerment |

| Transcendence | ||||

| Psychological | Maternal denial of child's illness; maternal anxiety and fear | Increased family understanding and acceptance of the illness; reduction of maternal anxiety and fear in caregiving | Explaining about the illness and how to control symptoms with medication to the family | Maternal self-efficacy in care (maintaining child's skin integrity, gavage feeding, physiotherapy and occupational therapy); acceptance of the illness and change in negative attitude |

Actual nursing diagnoses based on the framework included:

- Ineffective airway clearance: Related to neuromuscular impairment and ineffective cough, as evidenced by cough, shortness of breath, and abnormal vital signs upon admission.

- Impaired physical mobility: Related to neuromuscular impairment and muscle spasticity, as evidenced by leg deformities and limited movement.

- Impaired skin integrity: Related to prolonged immobility, as evidenced by the need for frequent repositioning and daily skin checks.

- Imbalanced nutrition (less than body requirements): Related to difficulty swallowing and poor appetite, as evidenced by low weight and height for age.

- Interrupted family processes: Related to a chronically ill child and lack of support from health institutions, as evidenced by the mother's significant stress and the brother's jealousy.

Potential nursing diagnoses based on the framework included:

- Risk for aspiration: Related to decreased gag and cough reflexes and impaired swallowing.

- Risk for injury: Related to seizure activity and muscular spasms.

- Risk for infection: Related to colostomy history, compromised physical mobility, and decreased level of consciousness upon admission.

There are three types of comfort interventions:

1. Standard and technical comfort interventions: These are related to maintaining homeostasis, including monitoring vital signs and administering medication.

2. Coaching interventions: This type of intervention helps to relieve anxiety, provide reassurance and information, instill hope, and involves listening and suggesting a desired program for improvement through cultural sensitivity.

3. Interventions for the soul: These are interventions that patients usually do not expect, but if performed, they are very satisfying, such as a massage (12).

Interventions were as follows:

1. Ineffective airway clearance: Chest physiotherapy, changing position every two hours, warm steam inhalation, oxygen therapy as needed, and monitoring respiratory status.

2. Aspiration: Elevating the head of the bed, education on gavage and lavage, using a pacifier to strengthen swallowing and jaw muscles, and gavage feeding as tolerated.

3. Impaired skin integrity: Changing position every two hours, checking for bedsores and other skin areas daily, and ensuring sheets and clothing are smooth and wrinkle-free.

4. Risk of injury and trauma: Keeping the bed rails up, using soft padding for bed rails, and placing the child on their side during seizures.

5. Imbalanced nutrition: Providing small, frequent feedings, high-protein and nutritious foods, assessing and calculating caloric intake, and increasing it as needed.

6. Interrupted family processes: Allowing parents to express feelings and ask questions, providing emotional and psychological support to the family, guiding them for referral to appropriate services, and encouraging other family members to participate in care.

According to the comfort daisies tool, the comfort score before interventions was 2 (poor condition). After the interventions, the comfort level score reached 4 (very good condition) (Figure 2). Changes in comfort dimensions (pre- and post-intervention) were observed (Table 4).

| Context | Relief | Ease | Transcendence |

|---|---|---|---|

| Physical | Pre: Fever, cough, seizures, low SpO₂ (92%), and skin rash; post: No seizures, SpO2: 95 - 100%, no skin lesions | Pre: Discomfort due to environment and spasticity; post: Improved relaxation, better sleep, and muscle relaxation | Pre: Passive during care, low response to therapy; post: Increased responsiveness during care, calmer status |

| Psychological | Pre: Maternal anxiety, denial of diagnosis; post: Acceptance, reduced anxiety | Pre: Mother fearful of feeding and care; post: More confident, improved maternal role perception | Pre: Overwhelmed mother; post: Greater emotional strength, coping with chronic illness |

| Social-cultural | Pre: Social isolation, minimal family involvement; post: Brother and father more engaged | Pre: Mother alone in care; post: Others assisting in caregiving | Pre: No peer/parental communication; post: Mother open to seeking support networks |

| Environmental | Pre: High noise levels, shared room; post: Private room, improved rest | - | - |

3. Discussion

The results of the study showed that one of the most important needs regarding children with CP is the need for parental acceptance of the illness and increased awareness, which leads to reduced anxiety and fear in caring for the child (5). In this regard, the results of the study by Ghashghaee et al. are consistent with the results of this study, showing that education for parents of children with CP about care issues is very important and is considered a key component in the child's treatment (13). The results of the study by Nobakht et al. also showed that education for caregivers of children with CP has a positive effect on the caregiver's mental health, as well as on the child's participation in daily activities and their gross and fine motor function (14). The results of the study by Derya and Pasinlioglu also showed that nursing care based on comfort theory meets the comfort needs of women after cesarean section and increases their postpartum comfort level (15). This study was conducted on postpartum women, but in our study, comfort theory was applied to a child with CP.

Sharma et al. used this theory as a framework for patient assessment, identifying needs, and providing comfort interventions (8). Notably, Kolcaba and DiMarco (16) discussed the framework’s applicability to pediatric nursing. A case study of a 5-year-old child recovering from laparotomy in the PICU also demonstrated improved comfort after interventions based on Kolcaba’s framework (7). Similarly, a case report involving a child with cancer highlighted the theory’s practical utility for pediatric oncology nursing (17). Our findings align with the mentioned studies, showing that interventions across the physical, psychological, socio-cultural, and environmental domains contributed to significant gains in relief (absence of symptoms), ease (improved rest and caregiver confidence), and transcendence (greater coping and emotional adaptation). The use of Kolcaba's comfort theory increased the level of comfort and was effective in providing comprehensive care for the child and family.

This study has several limitations, such as its case report design, the absence of validated Persian comfort measurement tools specific to children with CP, lack of long-term follow-up, and reliance on descriptive rather than objective clinical outcomes, which is recommended to be considered in future studies. Further studies should be conducted in other medical centers and with other populations using an experimental design to evaluate comfort theory’s efficacy, employing longer follow-up periods, and objective clinical measures such as functional motor scores.