1. Background

A childhood cancer diagnosis constitutes a profound trauma that affects the entire family, exposing caregivers to both acute and chronic stress over extended periods (1). Each year, approximately 400,000 new pediatric cancer cases are identified worldwide; in Iran, the age-standardized incidence rate stands at 119.56 per million children aged 0 - 19 years, with leukemia being the most prevalent diagnosis (2). Mothers, as primary caregivers, shoulder the greatest emotional and logistical burden, providing consistent support, coordination, and stability for both the child and the broader family unit (3). This relentless caregiving role — amid invasive treatments and persistent fears of recurrence — substantially increases the risk of severe mental health problems (4). Research consistently demonstrates high rates of depression, anxiety, post-traumatic stress symptoms, and elevated perceived stress among these mothers, which can persist for years after the end of treatment (5). Meta-analyses report pooled prevalence rates of 21% for anxiety, 28% for depression, and 26% for post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) among parents of pediatric cancer patients (6). Addressing this psychological distress is critical, as caregiver well-being profoundly influences the child’s adaptation to illness and overall family functioning.

Within such chronic adversity, resilience emerges as an indispensable psychological resource. Resilience is conceptualized as the capacity to adapt effectively to significant stressors, trauma, or hardship; it is not merely the absence of symptoms, but rather a dynamic process of recovery and restoration of psychological equilibrium (7, 8). For mothers navigating the unpredictable and emotionally charged journey of pediatric oncology, resilience enables them to confront uncertainty, regulate overwhelming emotions, and persist in caregiving roles without succumbing to exhaustion or hopelessness (9). The Connor-Davidson Resilience Scale (CD-RISC) and similar instruments capture this multidimensional construct, encompassing domains such as personal competence, trust in one’s instincts and tolerance of negative affect, positive acceptance of change and secure relationships, a sense of control, and spiritual influences (10). Therefore, interventions designed to strengthen these domains hold significant promise for enhancing long-term psychosocial well-being in this resilient yet heavily burdened population.

One promising intervention is compassion-focused therapy (CFT), developed by Paul Gilbert and grounded in evolutionary psychology (11). The CFT cultivates self-compassion by fostering a compassionate, understanding, and nurturing internal dialogue, thereby activating the brain’s soothing system to counteract threat-driven and achievement-focused responses (12). For caregivers struggling with self-reproach, guilt, and persistent pressure, self-compassion — extending to oneself the empathy typically reserved for loved ones — offers a powerful remedy for self-criticism and shame, both of which erode resilience (13). Previous studies have demonstrated that self-compassion interventions can significantly reduce despair, decrease emotional avoidance, and promote proactive coping, thus supporting resilience among parents of children with chronic illnesses, including cancer (14, 15). In essence, CFT directly addresses self-inflicted psychological suffering, providing a compassionate pathway to renewal and recovery (16).

In parallel, mindfulness-based cognitive therapy (MBCT) combines elements of mindfulness-based stress reduction (MBSR) and cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) to offer an alternative therapeutic approach (17). Central to MBCT is the cultivation of present-focused, nonjudgmental awareness — mindfulness — which empowers individuals to observe and disengage from ruminative or negative thought patterns (18). For mothers preoccupied with concerns about prognosis and uncertainty, MBCT’s emphasis on nonreactivity can be transformative: By perceiving thoughts as transient events rather than literal truths, participants can moderate worry, ease affective distress, and prevent recurrence of depressive symptoms (19). A growing body of evidence supports the efficacy of MBCT in clinical settings, demonstrating reductions in anxiety and depression, as well as improvements in self-regulation and emotional stability among mothers of children with chronic illnesses (20, 21).

Although both CFT and MBCT have well-documented benefits for mental health, few studies have directly compared their effects on the nuanced dimensions of resilience within this highly stressed cohort of mothers. The existing literature presents mixed findings regarding their relative effectiveness; for example, some studies report greater improvements in resilience from CFT, particularly in areas related to self-compassion and reduction of shame among caregivers (13, 14), whereas others highlight the advantages of MBCT in decreasing rumination and enhancing cognitive flexibility in parents under significant stress (20, 21). Determining whether compassion-driven self-soothing or mindfulness-facilitated cognitive distancing leads to greater gains in resilience is therefore crucial for informing the delivery of tailored, evidence-based support for this vulnerable group.

2. Objectives

This study aimed to evaluate and compare the effectiveness of CFT and MBCT in enhancing overall resilience and its five subscales among mothers of children with cancer.

3. Methods

3.1. Study Design

The present study utilized a quantitative research design, employing a randomized controlled clinical trial with a pre-test, post-test, and three-month follow-up structure.

3.2. Participants

The study population comprised mothers aged 25 - 45 years who served as primary caregivers for children undergoing active cancer treatment at Mofid Hospital, Tehran, between 2024 and 2025. Sample size was determined a priori using G*Power, assuming a medium effect size (f = 0.25) for repeated-measures ANOVA, α = 0.05, statistical power = 0.80, three groups, and two time points (pre- and post-test), resulting in a minimum requirement of 42 participants; 45 were recruited to allow for a potential 10% attrition rate. Eligible mothers were selected through convenience purposive sampling, met the inclusion and exclusion criteria, and were randomly assigned (n = 15 per group) to the CFT, MBCT, or control arms using Excel’s RAND function by an independent assistant. Inclusion criteria included appropriate age, caregiver role, confirmed pediatric cancer diagnosis, literacy, and provision of informed consent. Exclusion criteria comprised severe psychiatric disorders, concurrent psychological therapy, or more than two absences from intervention sessions. No attrition was observed; all participants completed assessments, enabling a complete-case analysis. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants. Blinding was not feasible due to the nature of group interventions; however, anonymous online self-reports were used to reduce bias. Assessor non-blinding was acknowledged as a limitation, arising from ethical and practical considerations.

3.3. Scales

Resilience was the primary outcome, assessed using the CD-RISC, introduced by Connor and Davidson in 2003 (10). This 25-item self-report instrument utilizes a 5-point Likert scale (0 = Not true at all; 4 = True nearly all the time), yielding total scores ranging from 0 to 100, with higher scores indicating greater resilience. The CD-RISC comprises five subscales: Personal competence, high standards, and tenacity; trust in one's instincts, tolerance of negative affect, and strengthening effects of stress; positive acceptance of change and secure relationships; sense of control and purpose; and spiritual influences. The original instrument demonstrated strong internal consistency (α = 0.89). The Persian version has also shown reliability in high-stress Iranian populations, such as in Nooripour et al.'s study (α = 0.90) (22). In the present study, Cronbach’s alphas were excellent: Pre-test (α = 0.93), post-test (α = 0.94), and follow-up (α = 0.92).

3.4. Data Collection

Following ethical approvals and recruitment, all 45 mothers completed the pre-test resilience assessment. To prevent cross-group contamination, intervention sessions for the experimental arms were scheduled on separate days in distinct conference rooms at Mofid Hospital, with explicit instructions prohibiting discussion of session content outside assigned groups. The CFT and MBCT groups, each consisting of 15 participants, received eight weekly 90-minute sessions over two months. Interventions were delivered onsite by a PhD-level clinical psychologist with over ten years of experience and specialized training in both approaches. The control group received standard medical care without psychological intervention, although MBCT was offered to this group after study completion. The CFT protocol followed Gilbert’s model (11), while MBCT was conducted in accordance with Segal et al.’s framework (23). Post-test assessments were administered immediately after the intervention, with a follow-up at three months. Details of the intervention protocols are summarized in Table 1.

| Sessions | CFT | MBCT |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Introduction: Psychoeducation on the three emotion regulation systems (threat, drive, soothing) | Automatic pilot: Introduction to mindfulness, moving from "doing" to "being", and the raisin exercise |

| 2 | Understanding the mind: The 'Tricky Brain' model; separating the self from the self-critic | Dealing with barriers: Working with difficulty; body scan meditation to cultivate present-moment awareness |

| 3 | Cultivating compassionate attributes: Safe place imagery and the development of the ideal compassionate self | Gathering the scattered mind: Becoming aware of the breath and cultivating focused attention |

| 4 | Compassionate rhythms: Practicing compassionate breathing and posture; using kind vocal tone | Recognizing aversion: Introduction to the concept of "allowing and letting be" with difficult experiences |

| 5 | Working with self-criticism: Compassionate letter writing; developing compassionate reasoning to manage harsh thoughts | Thoughts are not facts: Cognitive awareness and de-centering from depressive/anxious thought patterns |

| 6 | Overcoming blocks to compassion: Identifying fears, resistances, and common blocks to self-kindness | Working with difficulty: The 3-minute breathing space; applying mindfulness to challenging emotional states |

| 7 | Application: Using the compassionate self to manage daily challenges and caregiving stress | Self-care and relapse prevention: Identifying personal triggers and integrating mindful self-compassion practices |

| 8 | Consolidation: Integrating compassionate living; planning for future challenges and maintaining practice | Maintaining and extending practice: Reviewing progress and establishing a committed, mindful life plan |

Abbreviations: CFT, compassion-focused therapy; MBCT, mindfulness-based cognitive therapy.

3.5. Data Analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS version 26. Descriptive statistics were used to summarize the data. The primary hypotheses were evaluated using mixed repeated-measures ANOVA, with Bonferroni post-hoc tests employed to identify significant pairwise differences among the three groups across the pre-test, post-test, and follow-up phases.

3.6. Ethical Consideration

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Islamic Azad University, Sari Branch, Iran (IR.IAU.SARI.REC.1403.382), and conducted in strict accordance with ethical principles, including confidentiality, anonymity, and the participants’ right to withdraw at any time. The trial was registered with the Iranian Registry of Clinical Trials (IRCT20250506065619N1).

4. Results

The sample consisted of 45 mothers aged 25 - 45 years (34.2 ± 4.8), all serving as primary caregivers for children receiving treatment for various pediatric cancers at Mofid Hospital, Tehran. Demographically, 91.1% of participants were married, with a mean ± SD family size of 2.4 ± 0.9 children; 68.9% had attained at least a high school education. Baseline analyses revealed no significant differences among the groups in terms of age (F = 0.45, P = 0.644), education (χ2 = 1.23, P = 0.540), or income (F = 0.78, P = 0.462), thereby ensuring group comparability.

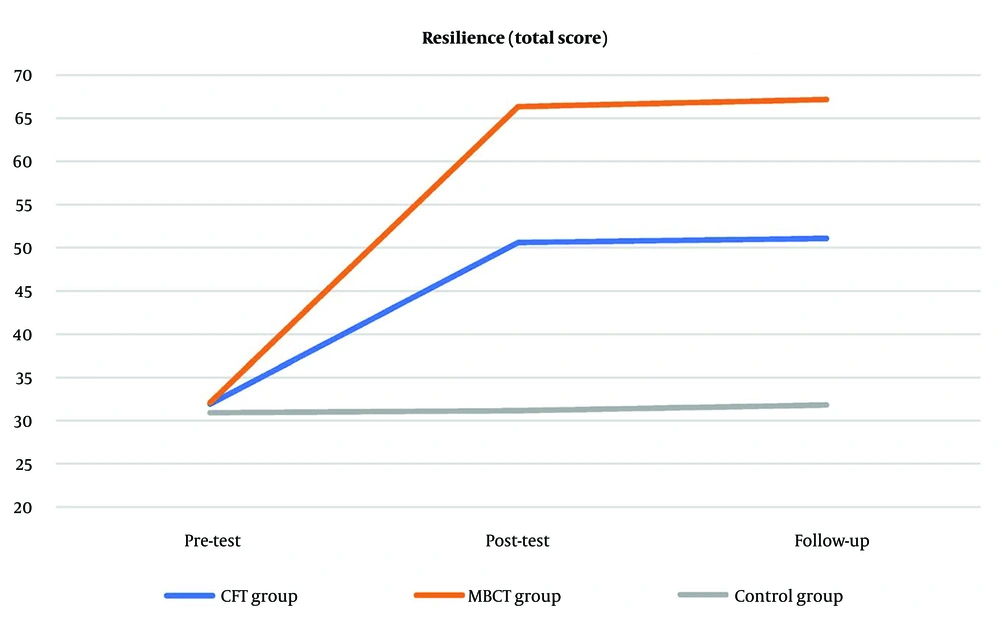

As shown in Table 2, pre-intervention resilience scores were equivalent across all groups, reflecting similar caregiving burdens at baseline. Following the interventions, both experimental groups exhibited marked improvements, with the MBCT group achieving the highest mean total resilience score (66.37 ± 8.36) as well as the greatest gains on subscales such as personal competence, compared to the control group, which remained stable. The follow-up assessment confirmed that these benefits were sustained over time.

| Variables | Pre-test | Post-test | Follow-up |

|---|---|---|---|

| Personal competence | |||

| CFT | 12.46 ± 2.66 | 17.78 ± 3.99 | 17.85 ± 3.97 |

| MBCT | 12.89 ± 2.61 | 21.68 ± 1.41 | 21.87 ± 1.92 |

| Control | 12.30 ± 1.83 | 12.44 ± 2.37 | 12.52 ± 2.36 |

| Trust in instincts, tolerance of negative affect | |||

| CFT | 9.27 ± 2.68 | 13.38 ± 5.83 | 13.51 ± 5.93 |

| MBCT | 9.13 ± 0.93 | 17.33 ± 5.82 | 17.41 ± 6.11 |

| Control | 9.11 ± 1.09 | 8.93 ± 1.36 | 9.33 ± 1.48 |

| Positive acceptance of change, and secure relationships | |||

| CFT | 5.76 ± 1.60 | 9.23 ± 1.06 | 9.40 ± 1.25 |

| MBCT | 5.60 ± 1.20 | 13.47 ± 5.39 | 13.60 ± 5.16 |

| Control | 5.21 ± 1.91 | 5.34 ± 1.05 | 5.38 ± 1.13 |

| Control | |||

| CFT | 3.10 ± 0.39 | 6.28 ± 1.93 | 6.35 ± 1.88 |

| MBCT | 3.20 ± 0.42 | 8.63 ± 1.54 | 8.96 ± 1.13 |

| Control | 3.10 ± 0.33 | 3.13 ± 0.65 | 3.23 ± 0.67 |

| Spiritual influences | |||

| CFT | 1.34 ± 0.23 | 3.92 ± 0.52 | 3.97 ± 0.49 |

| MBCT | 1.29 ± 0.25 | 5.27 ± 0.90 | 5.34 ± 0.91 |

| Control | 1.21 ± 0.37 | 1.32 ± 0.28 | 1.36 ± 0.27 |

| Resilience (total) | |||

| CFT | 31.93 ± 4.86 | 50.59 ± 8.90 | 51.08 ± 9.01 |

| MBCT | 32.10 ± 6.13 | 66.37 ± 8.36 | 67.18 ± 7.77 |

| Control | 30.93 ± 2.08 | 31.17 ± 2.97 | 31.82 ± 4.43 |

Abbreviations: CFT, compassion-focused therapy; MBCT, mindfulness-based cognitive therapy.

a Values are expressed as mean ± SD.

Figure 1 depicts the mean total resilience trajectories for the CFT, MBCT, and control groups across the pre-test, post-test, and follow-up phases.

Before conducting the repeated-measures ANOVA, all necessary assumptions were verified. Normality was confirmed using Shapiro-Wilk tests (all P > 0.05 across subscales and time points), homogeneity of variances was established with Levene's test (all P > 0.10), and sphericity was assessed via Mauchly's test. The analyses revealed significant main effects for group and time, as well as significant group × time interactions, indicating that the interventions differentially influenced resilience over the study period.

Notably, total resilience demonstrated a robust interaction effect (F = 36.75, P < 0.001, η2 = 0.54), highlighting the superior efficacy of MBCT in fostering adaptive recalibration in response to the ongoing demands of maternal caregiving. Bonferroni-adjusted analyses showed significant improvements from baseline to post-intervention (e.g., total resilience: ΔM ± SE = 17.73 ± 1.20, P < 0.001), with minimal changes observed between post-test and follow-up (ΔM ± SE = 0.65 ± 0.80, P = 0.999). These findings underscore the durability of the intervention's impact in strengthening resilience and maintaining mothers’ composure in the face of caregiving challenges.

Group-wise comparisons, detailed in Table 3, further underscore the superiority of MBCT, with significant differences favoring MBCT over both CFT and the control group (e.g., total resilience: The MBCT-control: Mean difference ± SE = 35.25 ± 1.58, P < 0.001; CFT-MBCT: Mean difference ± SE = -16.83 ± 1.45, P < 0.001). Subscale analyses mirrored these findings, particularly for the control subscale (MBCT-CFT: Mean difference ± SE = 1.69 ± 0.89, P < 0.001) and spiritual influences (MBCT-CFT: Mean difference ± SE = 1.35 ± 0.32, P < 0.001), while differences between the control group and both intervention groups remained consistently pronounced.

| Variables | Mean Difference ± SE | P |

|---|---|---|

| Personal competence | ||

| MBCT | ||

| Control | 6.39 ± 0.70 | 0.001 |

| CFT | ||

| Control | 3.61 ± 0.70 | 0.001 |

| MBCT | -2.78 ± 0.66 | 0.001 |

| Trust in instincts, tolerance of negative affect | ||

| MBCT | ||

| Control | 5.35 ± 1.00 | 0.001 |

| CFT | ||

| Control | 2.78 ± 1.00 | 0.001 |

| MBCT | -2.57 ± 1.18 | 0.001 |

| Positive acceptance of change, and secure relationships | ||

| MBCT | ||

| Control | 5.65 ± 0.95 | 0.001 |

| CFT | ||

| Control | 2.79 ± 0.95 | 0.001 |

| MBCT | -2.86 ± 1.03 | 0.001 |

| Control | ||

| MBCT | ||

| Control | 3.47 ± 0.80 | 0.001 |

| CFT | ||

| Control | 1.78 ± 0.80 | 0.001 |

| MBCT | -1.69 ± 0.89 | 0.001 |

| Spiritual influences | ||

| MBCT | ||

| Control | 2.67 ± 0.25 | 0.001 |

| CFT | ||

| Control | 1.78 ± 0.25 | 0.001 |

| MBCT | -0.89 ± 0.20 | 0.001 |

| Resilience (total) | ||

| MBCT | ||

| Control | 23.91 ± 1.50 | 0.001 |

| CFT | ||

| Control | 13.22 ± 1.50 | 0.001 |

| MBCT | -10.68 ± 1.82 | 0.001 |

Abbreviations: CFT, compassion-focused therapy; MBCT, mindfulness-based cognitive therapy.

5. Discussion

The present study conclusively demonstrates that both CFT and MBCT significantly enhanced overall resilience among mothers of children with cancer compared to the control group. This finding supports the primary hypothesis and is consistent with the broader literature on third-wave cognitive-behavioral therapies, which highlight the cultivation of internal resources and emotional self-regulation as critical buffers against chronic stress (24, 25). The persistent and unpredictable demands of pediatric oncology caregiving perpetually activate maternal threat systems, underscoring the necessity for interventions that foster adaptive coping strategies.

These results corroborate prior research, such as Khosrobeigi et al.’s evidence that self-compassion training improves parental resilience in pediatric cancer contexts (13), as well as Mehranfar et al.’s findings that MBCT enhances emotional regulation in highly stressful environments (26). Comparative studies further reinforce this pattern; for example, Frostadottir and Dorjee reported the superiority of MBCT over CFT in reducing rumination among individuals with depression and anxiety (17), which is consistent with our findings regarding cognitive flexibility subscales. Similarly, Millard et al.’s meta-analysis affirmed the efficacy of CFT in shame-prone populations while emphasizing MBCT’s advantage in sustaining emotional regulation (24), mirroring the enduring effects observed in the present study’s follow-up assessment. This investigation advances the field by directly comparing these two therapies within the specific context of pediatric oncology caregiving — an area where previous studies have typically evaluated them in isolation or across broader chronic illness populations (14, 20). The findings underscore the need for tailored, context-specific applications to optimize precision psychotherapy.

Although both therapies demonstrated notable efficacy, the key discovery lies in MBCT’s superiority in producing more pronounced enhancements in resilience within this demographic. This disparity likely results from the distinct operative mechanisms inherent to each intervention. The CFT primarily activates the affiliative soothing system to counter self-criticism and cultivate self-kindness (27). While this approach effectively alleviates internalized maternal guilt and self-reproach, MBCT additionally integrates cognitive reframing via de-centering practices (26). Mothers facing pediatric cancer frequently contend with acute, anticipatory anxieties — such as fears of relapse, treatment failure, and prolonged suffering — that foster entrenched rumination and catastrophizing (28). The MBCT’s core technique of viewing “thoughts as not facts” provides participants with a potent cognitive tool to disengage from maladaptive cycles and redirect focus toward present, constructive engagement (21, 26). This paradigm shift appears to yield more comprehensive improvements in resilience compared to compassion-based strategies alone.

Subscale analyses of the CD-RISC further demonstrate MBCT’s broader impact, showing significantly greater gains in most domains, particularly trust in instincts/tolerance of negative affect and control. Mindfulness cultivates nonjudgmental acceptance, enhancing tolerance for distressing emotions (25) — an essential skill for mothers enduring persistent adversity, as it facilitates adaptive emotional processing without avoidance or suppression. The elevated Control subscale scores in the MBCT group suggest diminished automatic negative cognition, restoring a sense of agency and efficacy amid complex caregiving challenges. While CFT substantially strengthened resilience through increased self-compassion, its focus may not fully engage the cognitive-behavioral mechanisms necessary for managing unchangeable stressors, which MBCT addresses through de-centering techniques.

Furthermore, the absence of significant differences between post-intervention and three-month follow-up assessments in both treatment arms robustly attests to the durability and consistency of these interventions' effects. This temporal invariance indicates that participants internalized compassion and mindfulness skills as enduring adaptive resources within their coping repertoire — an especially crucial achievement given the ongoing demands of caregiving stress.

5.1. Conclusions

In conclusion, while both CFT and MBCT are valuable psychotherapeutic interventions for mothers of children with cancer, the evidence from this study suggests that MBCT offers a comparative advantage by more comprehensively and robustly enhancing resilience — particularly through its capacity to reduce cognitive rumination and improve tolerance of difficult emotions. Clinical practitioners are therefore encouraged to prioritize MBCT as a frontline intervention, potentially supplemented by CFT to reinforce self-soothing capacities, thereby maximizing the therapeutic benefit for this vulnerable population.

5.2. Limitations

This study has notable limitations. The small sample size and convenience sampling from a single urban hospital in Tehran may limit generalizability to wider socioeconomic or rural populations. The lack of participant and facilitator blinding introduces potential performance and expectancy biases, as acknowledged in the methods section. The absence of stratification by cancer type (e.g., leukemia versus solid tumors) overlooks possible moderating variables such as prognosis and treatment demands; future studies should address these factors. Sole reliance on the self-report CD-RISC raises the possibility of social desirability and recall biases, highlighting the need for multi-method assessment approaches in future research.