1. Background

In recent years, psychology has emphasized positive emotions and their recognition and regulation. In preventive psychology, primary prevention is considered the most cost-effective strategy for promoting community mental health (1). Among positive emotions, happiness is a core component of psychological well-being and has attracted growing attention (2). It is viewed as a fundamental human need and a determinant of family and societal health, supporting hope, motivation, and progress (3).

Happiness is a subjective sense of well-being that includes positive emotions and life satisfaction, with low negative affect (4). It has two dimensions: Affective (pleasure/positive emotions) and cognitive (life satisfaction judgments) (5).

Many occupations involve chronic stress, which can negatively affect mental health, performance, and attendance (6). Employee happiness has become a strategic concern for institutions (7). In hospitals, nurses are a critical workforce due to sustained patient contact (8). Research in China has shown moderate happiness among nurses (9, 10), and studies in Iran have reported similar levels (11, 12).

Given nursing’s high stress, improving nurses’ happiness is important for well-being and care quality (13). Happiness is associated with better health, self-esteem, self-confidence, and quality of life (14).

Responsibility may be related to happiness (15). Higher happiness may strengthen informal networks, communication, and responsibility, potentially improving organizational commitment and attractiveness (16). Social responsibility is an ethical obligation across individuals, organizations, and governments and may support organizational performance and employee well-being (17). It reflects readiness to engage with society, uphold trust, and act with integrity. Beal defines social responsibility as commitment to policies and actions that promote societal, environmental, and human development interests alongside economic goals (18). Responsible behavior is linked to cognitive development, ethical awareness, social consciousness, and interpersonal competence (19).

With increasing national and global relevance, social responsibility is considered a driving force for societal advancement (20). Its presence supports ethical and lawful behavior, while its absence may lead to adverse societal consequences (21). In healthcare institutions, social responsibility can enhance organizational credibility and public trust (22). Nurses, as frontline providers, must uphold social responsibility through patient safety, ethical conduct, and equitable, high-quality care (23, 24).

Despite its importance, social responsibility remains underexplored in nursing, particularly in Iran. Few studies have examined its relationship with nurses’ happiness. Given its implications for healthcare delivery and staff well-being, further investigation is warranted.

2. Objectives

To investigate the relationship between social responsibility and happiness among nurses working in hospitals affiliated with Tehran University of Medical Sciences (TUMS).

3. Methods

3.1. Study Design

This analytical cross-sectional study was conducted in 2023 in 14 hospitals affiliated with TUMS, Iran, to examine the relationship between social responsibility and happiness among nurses.

3.2. Participants

The study population included all nurses employed in the selected hospitals (n = 5,162). Stratified random sampling was used (each hospital as a stratum) with proportional allocation, followed by simple random selection (lottery method) within strata.

Sample size calculation: The sample size was calculated using the standard formula for estimating the mean of a quantitative variable in a finite population:

In this formula, N denotes the population size (5,162 nurses), z represents the z-score for a 99% confidence level (z = 2.575), σ is the estimated standard deviation from prior studies (25), and d is the margin of error. Based on reported standard deviations for social responsibility (0.4) and happiness (11.5) in previous Iranian studies (26) and allowable errors of 0.1 and 2 respectively, the initial sample size was calculated as 210.33. Considering a 10% potential non-response rate, the final sample size was increased to 240 nurses.

3.3. Scales

3.3.1. Demographic Characteristics Questionnaire

Age, gender, education level, marital status, workplace department, job position, employment status, shift type, years of professional nursing experience, income level, satisfaction with income, and experience in caring for patients with COVID-19.

3.3.2. Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) Questionnaire Based on Carroll’s Model

The Carroll-based CSR Questionnaire contains 35 items across four dimensions: Legal (7), economic (7), ethical (9), and collegial (12) (25). Items are rated on a 5-point Likert scale (strongly disagree to strongly agree), yielding total scores from 35 to 175; higher scores indicate greater social responsibility. Total scores are categorized into four levels (very low, low, moderate, high), and selected items are reverse-scored. Previous Iranian research reported reliability of 0.81 (26). In this study, test-retest reliability over two weeks in 15 nurses was acceptable (r = 0.76); these participants were excluded from the main sample.

3.3.3. Oxford Happiness Questionnaire (OHQ)

The OHQ comprises 29 items rated on a 4-point scale (0 - 3) (27), with total scores ranging from 0 to 87 (higher scores indicate greater happiness). Scores are classified into four levels (low, moderate, high, very high). Test-retest reliability over two weeks in 15 nurses was r = 0.80.

3.4. Data Collection

After approvals and an official letter, selected nurses were invited through hospital nursing administrations. Study aims, confidentiality, and voluntary participation were explained; verbal consent was obtained. Questionnaires were self-administered and collected by the researcher.

3.5. Data Analysis

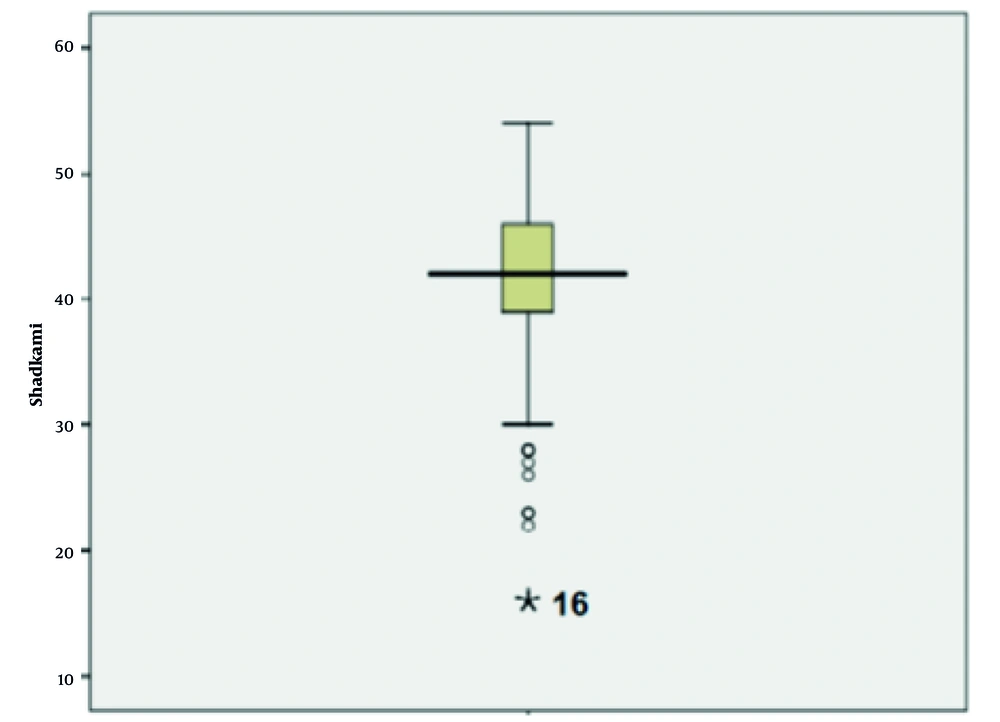

Analyses were performed using SPSS version 16. Descriptive statistics were calculated, and Pearson’s correlation coefficient was used to assess the relationship between social responsibility and happiness (P < 0.05). Data were screened for extreme outliers using SPSS boxplots; one extreme outlier in happiness was excluded, yielding a final sample of 239.

3.6. Ethical Consideration

The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of TUMS (IR.TUMS.FNM.REC.1401.054). Participants were informed about confidentiality and the right to withdraw without consequences; completion/return of questionnaires was considered consent.

4. Results

Initial screening identified one extreme outlier in happiness (score = 16) on SPSS boxplot (Figure 1). This case was excluded from further analyses, resulting in a final sample size of 239. Table 1 summarizes participants’ sociodemographic and occupational characteristics.

| Variables, Categories and Ranges | No. (%) |

|---|---|

| Gender | |

| Woman | 165 (69.0) |

| Man | 74 (31.0) |

| Marital status | |

| Single | 118 (49.4) |

| Married | 102 (42.7) |

| Divorced | 12 (5.0) |

| Widow | 7 (2.9) |

| Education | |

| Bachelor's degree | 216 (90.4) |

| Master’s degree | 23 (9.6) |

| Organizational post | |

| Head nurse | 6 (2.5) |

| Nurse | 233 (97.5) |

| Work shift | |

| Morning | 79 (33.1) |

| Evening | 6 (2.5) |

| Night | 23 (9.6) |

| Rotating | 131 (54.8) |

| Employment status | |

| Contractual | 19 (7.9) |

| Design-based | 62 (25.9) |

| Official | 30 (12.6) |

| Commissioned | 128 (53.6) |

| Income | |

| Less than expenses | 115 (48.1) |

| Equal to expenses | 119 (49.8) |

| Greater than expenses | 5 (2.1) |

| Income satisfaction | |

| Low | 128 (53.6) |

| Medium | 111 (46.4) |

| Care for COVID-19 patients | |

| Yes | 161 (67.4) |

| No | 78 (32.6) |

| Age (y) | |

| 21 - 24 | 2 (0.8) |

| 25 - 29 | 78 (32.7) |

| 30 - 34 | 67 (28.0) |

| 35 - 39 | 53 (22.2) |

| 40 - 44 | 31 (13.0) |

| 45 - 49 | 6 (2.5) |

| 50 - 53 | 2 (0.8) |

| Work experience (y) | |

| 1 - 4 | 86 (36.0) |

| 5 - 9 | 83 (34.7) |

| 10 - 14 | 55 (23.0) |

| 15 - 19 | 14 (5.9) |

| 20 - 23 | 1 (0.4) |

| Workplace department | |

| Internal | 58 (24.3) |

| Surgical | 52 (21.7) |

| Special | 43 (18.0) |

| Emergency | 29 (12.1) |

| Pediatrics | 21 (8.8) |

| Ophthalmology | 15 (6.3) |

| Obstetrics and gynecology | 10 (4.2) |

| Psychiatry | 9 (3.8) |

| Pediatric special | 2 (0.8) |

Table 2 indicates that happiness was predominantly moderate in this sample, with self-efficacy and hopefulness showing the highest subscale means and the remaining dimensions exhibiting similar mean values.

| Level/Statistics | Low a | Moderate a | High a | Very High a | Min-Max Score a | Mean ± SD |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Self-concept (0 - 24) | 1 (0.4) | 135 (56.5) | 103 (43.1) | 0 (0) | 5 - 15 | 10.7 ± 1.96 |

| Life satisfaction (0 - 12) | 4 (1.7) | 97 (40.6) | 137 (57.3) | 1 (0.4) | 2 - 9 | 5.5 ± 1.18 |

| Psychological readiness (0 - 12) | 1 (0.4) | 151 (63.2) | 85 (35.6) | 2 (0.8) | 1 - 10 | 5.2 ± 1.13 |

| Enthusiasm (0 - 6) | 10 (4.2) | 55 (23.0) | 170 (71.1) | 4 (1.7) | 1 - 5 | 2.8 ± 0.72 |

| Aesthetic feeling (0 - 15) | 1 (0.4) | 156 (65.3) | 82 (34.3) | 0 (0) | 2 - 10 | 7.0 ± 1.08 |

| Self-efficacy (0 - 12) | 1 (0.4) | 28 (11.7) | 133 (55.7) | 77 (32.2) | 2 - 11 | 7.5 ± 1.68 |

| Hopefulness (0 - 6) | 4 (1.7) | 49 (20.5) | 186 (78.0) | 0 (0) | 1 - 4 | 3.0 ± 0.72 |

| Total happiness (0 - 87) | 0 (0.0) | 137 (57.3) | 102 (42.7) | 0 (0.0) | 22 - 54 | 42.3 ± 5.85 |

a Values are expressed as No. (%).

Overall social responsibility was predominantly low: 68.2% of participants were classified as low and 28.5% as very low, with none classified as high or very high in the overall score (Table 3). The mean total social responsibility score was 68.1 ± 9.85, and the maximum observed score was 112 (moderate category), indicating generally low social responsibility in the sample.

| Responsibility Level | Overall Score | Legal | Economic | Ethical | Collegial |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Very low (35 - 62) | 68 (28.5) | 46 (19.2) | 63 (26.4) | 171 (71.6) | 86 (36.0) |

| Low (63 - 90) | 163 (68.2) | 173 (72.4) | 159 (66.5) | 61 (25.5) | 147 (61.5) |

| Moderate (91 - 118) | 8 (3.3) | 20 (8.4) | 17 (7.1) | 6 (2.5) | 6 (2.5) |

| High (119 - 146) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (0.4) | 0 (0) |

| Mean ± SD | 68.1 ± 9.85 | 14.6 ± 2.67 | 14.4 ± 2.66 | 15.7 ± 3.20 | 23.3 ± 3.84 |

a Values are expressed as No. (%) or unless otherwise indicated.

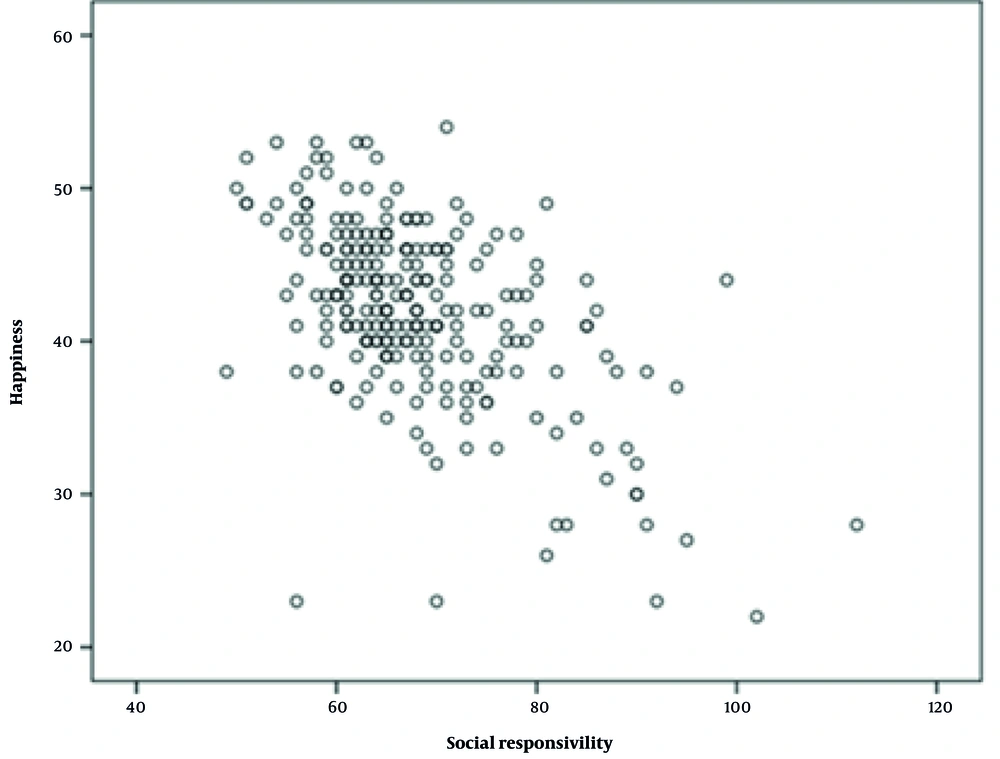

Pearson’s correlation showed a significant negative association between happiness and social responsibility (r = -0.56, P < 0.001) (Figure 2), indicating that higher social responsibility scores were associated with lower happiness scores in this sample.

5. Discussion

More than half of nurses reported moderate happiness, with no participants classified as very low or very high. This pattern is consistent with findings from Turkey and Iran reporting average-to-moderate happiness among nurses (28, 29). Given nursing’s high physical and psychological demands, sustained stress may limit happiness; nevertheless, happiness has been linked to reduced workplace tension and fatigue and to higher job satisfaction, organizational commitment, and emotional engagement (30). Differences from studies reporting lower happiness among healthcare workers may reflect contextual factors such as the COVID-19 period and related work pressures (31).

Self-efficacy and hopefulness showed the highest mean scores among happiness dimensions, suggesting that perceived capability and optimism about the future may contribute to overall happiness. Prior studies similarly report positive associations between self-efficacy and nurses’ general health and well-being (32, 33). The remaining dimensions showed relatively comparable means, indicating broadly balanced contributions to happiness.

Overall social responsibility was predominantly low or very low. This may reflect challenges in meeting professional obligations under high workload or feeling that responsibility exceeds clinical competence, particularly in complex care situations (34). High job demands and stress may also weaken perceived social responsibility (30). However, other Iranian studies have reported moderate-to-high social responsibility among nurses, suggesting that setting, organizational context, or measurement differences may influence observed levels (35, 36).

Component scores of social responsibility generally ranged from very low to moderate, indicating a need to strengthen professional responsibilities, particularly ethical practice within hospital settings. Workload, limited resources, administrative constraints, and psychological pressure may reduce attention to ethical considerations. Consistent with this explanation, Keikha et al. reported lower ethical/humanitarian components and found that adherence to professional ethics predicts nurses’ social responsibility (22).

The present study found an inverse relationship between nurses’ happiness and social responsibility, such that higher social responsibility was associated with lower happiness. Consistent with this finding, Khani et al. reported that social responsibility significantly contributes to explaining nurses’ happiness (37). Likewise, Beikzad et al. reported a significant association between social responsibility and nurses’ job satisfaction (38). A plausible explanation is that greater responsibility increases decision burden, exposure to high-stakes situations, and emotional labor, which may heighten fatigue and work–life conflict and reduce opportunities for recovery, thereby lowering happiness.

However, evidence is not uniform. Ahmad et al. found that organizational social responsibility was negatively associated with nurse burnout (39). These findings suggest that in supportive organizational contexts, responsibility may be accompanied by better mental well-being and compassion, potentially buffering burnout and sustaining happiness.

5.1. Conclusions

In this study, nurses generally showed moderate happiness and low social responsibility. Happiness was negatively associated with social responsibility. Managers should promote social responsibility alongside measures that reduce workload-related strain and support nurses’ well-being, integrating social responsibility into organizational policies and training.

5.2. Limitations

This study has limitations. First, the sample was drawn from TUMS-affiliated hospitals, which may limit generalizability to other regions and institutions. Second, data were collected using self-report measures, which are subject to response and social desirability biases. Third, despite assurances of confidentiality and anonymity, participation may have been influenced by concerns about privacy. Finally, due to the cross-sectional design, the observed inverse association between happiness and social responsibility cannot be interpreted causally. Unmeasured factors (e.g., workload, staffing levels, moral distress, and organizational support) may confound this relationship. Future longitudinal and interventional studies are needed to clarify directionality.