1. Background

Prostate cancer (PCa) is the most prevalent non-skin cancer affecting men worldwide (1). Despite advances in the diagnosis and treatment of PCa, there are still 1,600,000 cases and 366,000 deaths reported annually in the United States alone (2). The prevalence varies among countries with diverse cultures and climates; for example, it is 5.13% in Turkey, 7.23% in Egypt, and 8.23% in the Arab Gulf states collectively (3).

This disease is characterized by high occurrence, with approximately 80 - 85% of PCa originating from the peripheral zone of the prostate gland. In addition, metastatic PCa ranks as the third-leading cause of cancer-related deaths (1, 4). Over 80% of men diagnosed with PCa also exhibit histological evidence of benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH), either with or without clinical symptoms (4). The BPH is the most common urological condition in elderly males globally. The BPH leads to an increase in prostate size and is associated with bladder outlet obstruction and various lower urinary tract symptoms (5). The BPH can also result in the decline of urinary function and quality of life, as well as a higher risk of urinary tract infection (UTI) and acute urine retention, often requiring surgical intervention. Furthermore, the costs associated with BPH management are substantial, even though many men go undiagnosed and receive inadequate treatment (6).

Prostate-specific antigen (PSA) is a serine protease produced by prostate epithelial cells under androgen regulation, belonging to the tissue kallikrein family. Elevated serum PSA levels are common in PCa and other conditions, making it a key marker for prostate diseases. The PSA expression is primarily regulated by androgens via the androgen receptor (7). In BPH, prostate volume and serum PSA levels are critical progression factors, with volumes greater than 30 mL and PSA greater than 1.5 ng/mL posing the highest risks (8). The PSA levels are relevant to BPH diagnosis as they reflect prostate epithelial activity and hyperplasia, while hematological parameters [e.g., those from complete blood count (CBC)] may indicate underlying inflammation or systemic responses often associated with BPH progression. Focusing on hematological traits is rational because they are routinely measured, cost-effective, and may serve as accessible biomarkers in resource-limited settings, potentially correlating with PSA and prostate volume through shared inflammatory pathways (9).

Various diagnostic methods for BPH rely on PSA measurement and ultrasound-based prostate volume assessment, supplemented by digital rectal examination. However, there is a need for simpler and more affordable alternatives, particularly in under-equipped facilities. Routine CBC-differential tests, part of initial assessments, could provide phenotypic correlations with PSA and prostate volume, aiding evaluation when ultrasound or PSA testing is unavailable. Predictive models based on these parameters might reduce the frequency of repeated tests.

2. Objectives

This study hypothesizes that hematological parameters correlate with serum PSA concentration and prostate volume in BPH patients, potentially enabling predictive models to improve PSA estimation and elucidate the hematological impacts on BPH. We aimed to explore these correlations in patients admitted to the urology department of Ashayer Hospital in 2021 - 2022, focusing on both prediction enhancement and mechanistic insights.

3. Methods

3.1. Study Design and Participants

An analytical retrospective study was conducted using a census method, including all patients diagnosed with BPH admitted to the Urology Department of Ashayer Hospital between January 1, 2021, and January 1, 2022.

3.2. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

Patients diagnosed with BPH at Ashayer Hospital with complete medical records, including hematological parameters, serum PSA levels, and prostate volume assessed by transabdominal ultrasound, were included. Exclusion criteria comprised patients with hematological diseases, chronic conditions (e.g., chronic kidney disease), incomplete records, recent use of prostate-reducing drugs (e.g., 5-alpha reductase inhibitors), smokers, vegetarians, hereditary disorders (e.g., thalassemia minor), or those expressing dissatisfaction with laboratory or ultrasound results.

3.3. Data Collection Instruments

Data were collected from laboratory tests and transabdominal ultrasound reports. Hematological parameters were measured uniformly using standard laboratory protocols upon hospital admission, employing automated analyzers following institutional guidelines to ensure consistency. Prostate volume was calculated using the ellipsoid formula from ultrasound dimensions.

3.4. Procedure

After obtaining ethical approval from Lorestan University of Medical Sciences (IR.LUMS.REC.1401.310), patient files were retrieved from hospital archives. Data, including hematological parameters, serum PSA levels, prostate volume, and demographics (e.g., age), were extracted using a standardized checklist and entered into Excel for initial organization, then transferred to SAS software. Missing data were supplemented via telephone or in-person document review; unsuccessful cases were excluded. Hematological data and PSA measurements were validated through cross-checking with original laboratory reports for accuracy. Informed consent was waived due to the retrospective nature of the study, as approved by the ethics committee.

3.5. Data Analysis

Analyses were performed using SAS software (SAS Institute, 2003). The steps included:

- UNIVARIATE procedure to check normality (using skewness and kurtosis); non-normal data (e.g., neutrophil and lymphocyte percentages) were log-transformed.

- PROC MEANS for descriptive statistics (mean, variance, standard deviation, standard error).

- PROC REG for linear regression coefficients between prostate volume/PSA (dependent variables) and 12 hematological parameters (independent variables), with plots and statistics.

- PROC CORR for Pearson correlation coefficients.

- PROC REG for tolerance testing and variance inflation factor (VIF) to assess multicollinearity; variables with tolerance less than 0.1 or VIF greater than 10 were considered collinear.

- PROC REG with stepwise, forward, and backward selection methods to build multiple linear regression models, selecting based on maximum R2 and P < 0.05 for variable entry/retention; model validity prioritized higher R2 and lower multicollinearity.

4. Results

4.1. General Examination of Traits in the Target Population

In this study, 15 quantitative variables were evaluated in patients with BPH. The basic statistics related to these variables are presented in Table 1. All variables exhibited considerable variance (standard deviation squared), indicating potential influences by various physiological or environmental factors. Notably, the average prostate volume and PSA concentration were 82.66 mL and 3.76 units, respectively, in the study population with an average age of 71.75 years (861 months). It was anticipated that the average PSA concentration in this cohort would be higher. The results of the normality test using the UNIVARIATE procedure demonstrated that all data, except for the percentage of neutrophils and lymphocytes, deviated from a normal distribution. For these variables, the data were log-transformed to approximate a normal distribution.

| Variables | Number | Mean ± SD | SE | Variance | Skewness | Kurtosis |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Prostate volume | 133 | 82.66 ± 38.08 | 3.30 | 1449.89 | 1.24 | 2.19 |

| PSA | 164 | 3.76 ± 3.26 | 0.25 | 10.60 | 1.60 | 3.18 |

| Age | 164 | 860.82 ± 133.04 | 10.39 | 17695.75 | -0.05 | -0.81 |

| WBC | 164 | 7.14 ± 2.47 | 0.19 | 6.10 | 1.27 | 3.41 |

| RBC | 165 | 4.77 ± 0.70 | 0.05 | 0.50 | 0.18 | 0.55 |

| Hb | 165 | 14.14 ± 2.08 | 0.16 | 4.31 | -0.12 | 0.01 |

| HCT | 165 | 42.02 ± 5.53 | 0.43 | 30.60 | -0.04 | 0.14 |

| MCV | 165 | 88.63 ± 6.75 | 0.53 | 45.54 | -1.14 | 2.54 |

| MCH | 165 | 29.87 ± 2.68 | 0.21 | 7.17 | -1.21 | 4.85 |

| MCHC | 165 | 33.61 ± 1.94 | 0.51 | 3.77 | 0.77 | 4.12 |

| PLT | 165 | 231.15 ± 78.71 | 6.13 | 6196.02 | 1.18 | 2.04 |

| Nutr | 153 | 64.17 ± 12.26 | 0.99 | 150.42 | 0.30 | -0.41 |

| Lymph | 157 | 27.60 ± 10.76 | 0.86 | 115.81 | -0.20 | -0.63 |

| MXD | 146 | 8.81 ± 3.75 | 0.31 | 14.05 | 0.52 | 0.66 |

| RDW | 155 | 12.77 ± 2.20 | 0.18 | 4.85 | -0.45 | 2.97 |

Abbreviations: PSA, prostate-specific antigen; WBC, white blood cell; RBC, red blood cell; MCV, mean corpuscular volume; MCHC, mean corpuscular hemoglobin concentration; RDW, red cell distribution width.

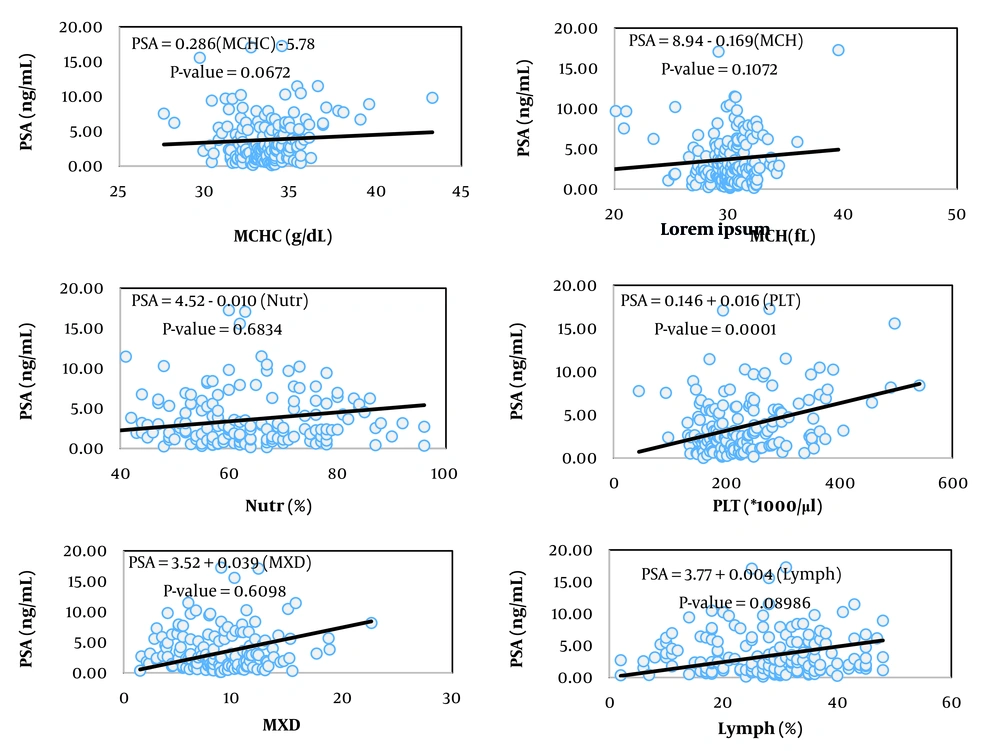

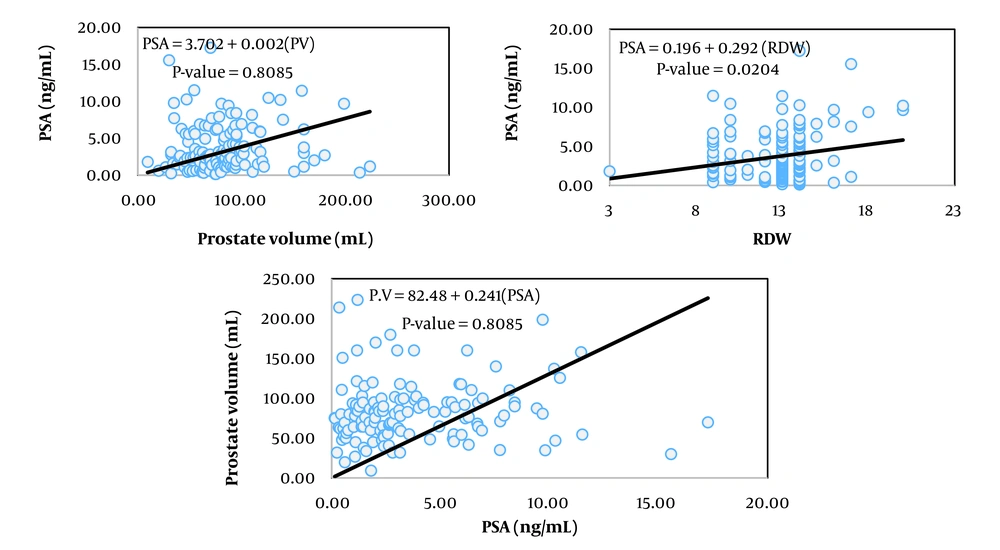

4.2. Investigating Linear Dependence of Prostate Volume and Prostate-Specific Antigen Level on the Evaluated Hematological Traits

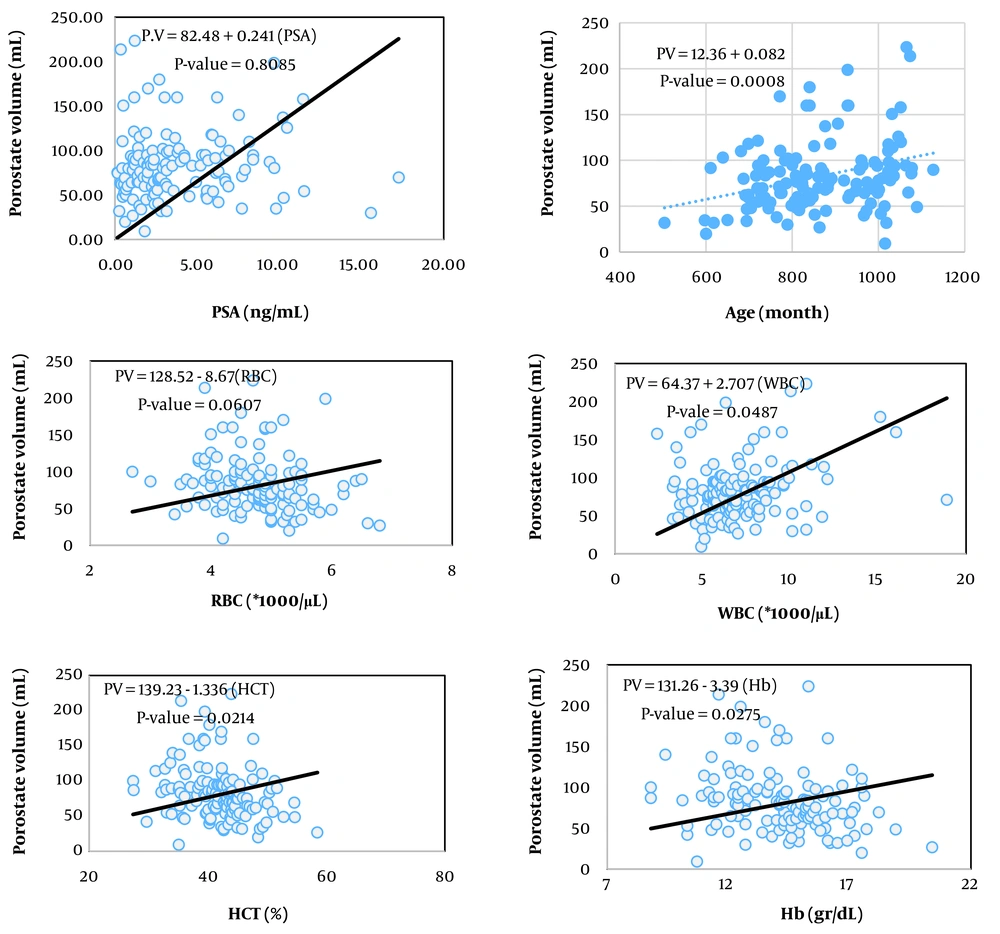

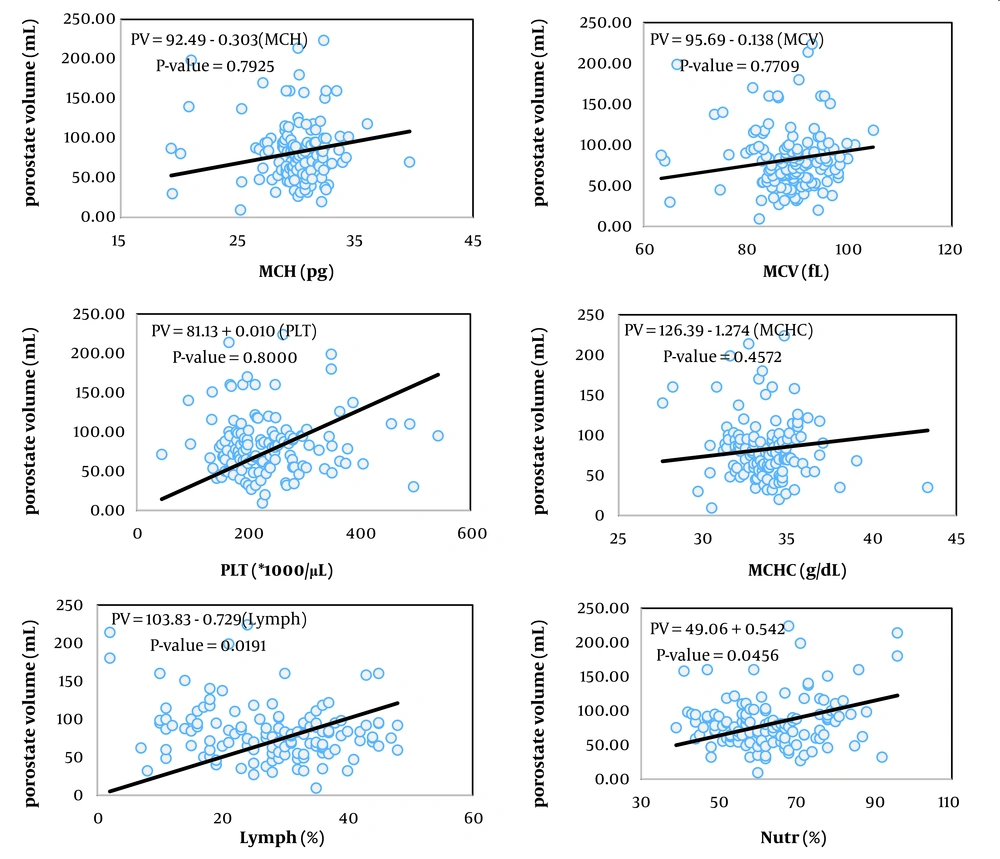

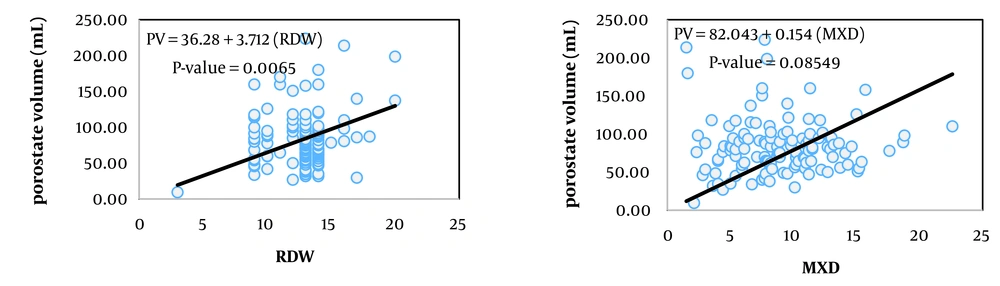

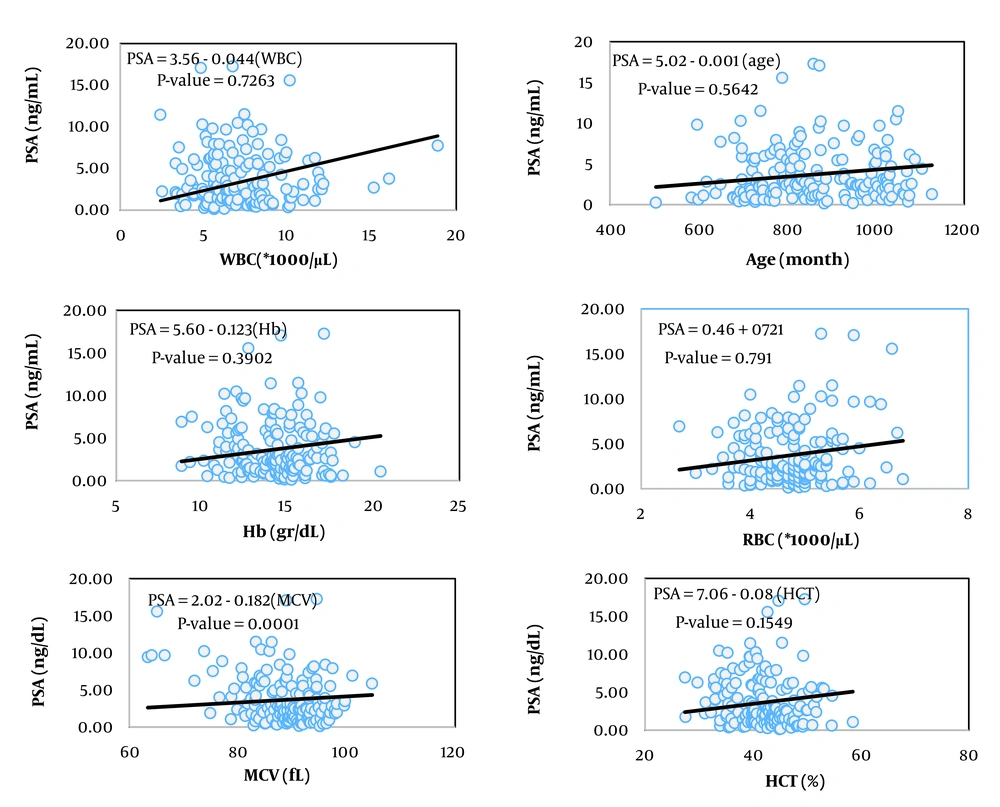

The simplest measure to assess the relationship between two variables is their covariance. Biologically, covariance represents the part of the variance of two traits created by common factors. However, the unit of covariance is the product of the units of the two variables, which complicates interpretation. To address this, the covariance of two traits is divided by the variance of the independent trait, resulting in the coefficient of correlation, which essentially expresses the covariance between two traits as a relative proportion of the variance of the independent trait. The unit of this coefficient is the unit of the dependent variable divided by the unit of the independent variable. In Tables 2, the coefficients of correlation for the variables of prostate volume and PSA (as dependent variables) from 13 hematologic traits (as independent variables) are presented, showing statistically significant relationships in the respective models.

| Variables | Prostate Volume | PSA | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Citizenship Coefficient | P-Value | Citizenship Coefficient | P-Value | |

| Prostate volume | - | - | 0.242 | 0.8085 |

| PSA | 0.242 | 0.8085 | - | - |

| Age | 0.082 | 0.0008 | -0.001 | 0.5642 |

| WBC | 2.707 | 0.487 | 0.044 | 0.7263 |

| RBC | -8.674 | 0.0602 | 0.721 | 0.0891 |

| Hb | -3.396 | 0.0275 | -0.123 | 0.3902 |

| HCT | -1.337 | 0.0214 | -0.076 | 0.1549 |

| MCV | -0.139 | 0.7709 | -0.182 | 0.0001 |

| MCH | -0.303 | 0.7925 | -0.169 | 0.1072 |

| MCHC | -1.274 | 0.4572 | 0.286 | 0.0672 |

| PLT | 0.0096 | 0.8100 | 0.016 | 0.0001 |

| Nutr | 0.542 | 0.0456 | -0.010 | 0.6834 |

| Lymph | -0.730 | 0.0191 | 0.004 | 0.8986 |

| MXD | 0.154 | 0.8546 | 0.039 | 0.6098 |

| RDW | 3.713 | 0.0065 | 0.292 | 0.0204 |

Abbreviations: PSA, prostate-specific antigen; WBC, white blood cell; RBC, red blood cell; MCV, mean corpuscular volume; MCHC, mean corpuscular hemoglobin concentration; RDW, red cell distribution width.

Among the studied traits, the linear correlation of prostate volume was significant with patient age, red blood cell (RBC) count, hemoglobin concentration, hematocrit percentage, neutrophil percentage, and red cell distribution width (RDW, P < 0.05). In contrast, the linear correlation of PSA blood level was significant with mean corpuscular volume (MCV), platelet count, and RDW.

Figures 1 to 6 illustrate linear relationships between all studied traits and the two variables, prostate volume and PSA blood level. Although, in clinical settings, an increase in PSA secretion is indicative of benign or malignant hyperplasia of the prostate, the results showed that the linear correlation between both variables was very weak. The coefficient of correlation for a dependent variable from an independent variable indicates the number of units of change in the dependent variable per unit change in the independent variable. In this study, the highest coefficient of correlation for prostate volume was observed, in descending order, for RBC count, RDW, hemoglobin concentration, and white blood cell (WBC) count. Meanwhile, the highest coefficient of correlation for PSA concentration was observed, in descending order, for RBC count, RDW, mean corpuscular hemoglobin concentration (MCHC), and MCV.

4.3. Investigating Pearson Correlation Between Prostate Volume, Prostate-Specific Antigen Level, and Evaluated Hematological Traits

Because the unit of the coefficient of correlation is expressed as the ratio of the dependent variable unit to the independent variable unit, physiological interpretation is not straightforward. Therefore, another measure, the correlation coefficient, is used. It is obtained by dividing the covariance between the two variables by the product of their standard deviations. This measure is dimensionless and provides a simple representation of the relationship between two variables (Table 3).

| Variables | Prostate Volume | PSA | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| R | P-Value | R | P-Value | |

| Prostate volume | 1.000 | - | 0.063 | 0.475 |

| PSA | 0.063 | 0.475 | 1/000 | - |

| Age | 0.278 | 0.001 | 0.026 | 0.741 |

| WBC | 0.218 | 0.012 | 0.007 | 0.930 |

| RBC | -0.201 | 0.021 | 0.145 | 0.061 |

| Hb | -0.251 | 0.003 | -0.070 | 0.031 |

| HCT | -0.250 | 0.772 | -0.111 | 0.155 |

| MCV | -0.037 | 0.673 | -0.316 | 0.0001 |

| MCH | -0.025 | 0.772 | -0.111 | 0.155 |

| MCHC | -0.139 | 0.112 | -0.139 | 0.081 |

| PLT | -0.034 | 0.670 | 0.305 | 0.0001 |

| Nutr | 0.184 | 0.040 | 0.038 | 0.647 |

| Lymph | -0.240 | 0.006 | -0.240 | 0.006 |

| MXD | 0.024 | 0.789 | 0.077 | 0.357 |

| RDW | 0.198 | 0.026 | 0.198 | 0.026 |

Abbreviations: PSA, prostate-specific antigen; WBC, white blood cell; RBC, red blood cell; MCV, mean corpuscular volume; MCHC, mean corpuscular hemoglobin concentration; RDW, red cell distribution width.

Prostate volume showed a significant correlation with patient age, RBC count, WBC count, hemoglobin concentration, hematocrit percentage, neutrophil count, and RDW (P < 0.05). The highest correlations were, in descending order, with patient age, hemoglobin concentration, and hematocrit percentage. The correlation coefficient of prostate volume with most traits related to RBCs and hemoglobin was negative.

The Pearson correlation coefficients between RBC count, hemoglobin concentration, MCV, platelet count, neutrophil percentage, and RDW were significant. Although all correlation coefficients were statistically described as low, the correlation coefficient between PSA and MCV and platelet count was higher than for other traits. Similar to prostate volume, the correlation coefficient between PSA and most traits related to hemoglobin concentration was negative. Among the set of traits studied, the correlation coefficients between RBC count, hemoglobin concentration, lymphocyte percentage, and RDW with both prostate volume and PSA level were significant and mostly had the same sign and numerically consistent, suggesting the possibility of shared physiological pathways for changes in both traits.

4.4. Investigating Linear Alignment Among the Evaluated Hematological Trait Variables

Tolerance test results are presented in Table 4. The lowest tolerance and highest VIF were observed for neutrophil percentage, lymphocyte percentage, RBC count, hemoglobin concentration, and hematocrit percentage, indicating high collinearity. Values near 1 for age, WBC count, platelet count, and RDW indicated low collinearity and thus suitability for inclusion in models.

| Variables | Parameter Estimation | SE | t-Value | Significant Probability | Tolerance | Variance Inflation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 0.073 | 0.025 | 2.88 | 0.0048 | 0.824 | 1.212 |

| WBC | 1.192 | 1.453 | 1.51 | 0.1344 | 0.760 | 1.316 |

| RBC | -6.407 | 35.903 | -0.18 | 0.8587 | 0.014 | 71.208 |

| Hb | -5.154 | 11.930 | -0.43 | 0.6666 | 0.014 | 70.133 |

| HCT | 0.909 | 4.292 | 0.21 | 0.8328 | 0.016 | 63.750 |

| MCV | -1.861 | 1.991 | -0.93 | 0.3520 | 0.048 | 20.911 |

| MCH | 4.868 | 4.723 | 1.03 | 0.3050 | 0.050 | 20.084 |

| MCHC | 1.091 | 3.469 | 0.31 | 0.7538 | 0.205 | 4.885 |

| PLT | 0.011 | 0.043 | 0.26 | 0.7917 | 0.713 | 1.403 |

| Nutr | 2.390 | 2.570 | 0.93 | 0.3544 | 0.009 | 105.535 |

| Lymph | 2.119 | 2.550 | 0.83 | 0.4078 | 0.013 | 78.290 |

| MXD | 3.123 | 2.648 | 1.18 | 0.2409 | 0.085 | 11.834 |

| RDW | 4.810 | 1.457 | 3.30 | 0.0013 | 0.757 | 1.321 |

Abbreviations: WBC, white blood cell; RBC, red blood cell; MCV, mean corpuscular volume; MCHC, mean corpuscular hemoglobin concentration; RDW, red cell distribution width.

4.5. Linear Multivariate Regression Models to Estimate Prostate Volume and Prostate-Specific Antigen Level Using Evaluated Hematological Traits

Table 5 presents the best multivariable linear models (based on the coefficient of determination, R2) for estimating prostate volume and PSA concentration using various modeling methods in the software employed. For prostate volume, the maximum R2 was 0.22 (forward method); stepwise and backward methods yielded similar results with four variables. For PSA, R2 ranged from 0.51 to 0.54 across methods (indicating higher validity than prostate volume models, likely due to stronger correlations); common variables included RBC count, MCH, MCHC, platelet count, hemoglobin, and RDW. Patient age was not included in PSA models. Orthogonal modeling did not improve R2.

| Estimation Methods | The Dependent Variable | Estimation Model | R2 (P > 0.05) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Stepwise | Prostate volume | (Age × 0.083) + (WBC × 2.466) + (RDW × 3.684) - 52.099 | 0.22 (< 0.0001) |

| Forward | Prostate volume | (Age × 0.086) + (WBC × 2.641) + (MCH × 0.879) + (MXD × 0.567) + (RDW × 3.665) – (-89.96) | 0.24 (0.0004) |

| Backward | Prostate volume | (Age × 0.083) + (WBC × 2.466) + (RDW × 3.684) - 52.10 | 0.22 (< 0.0001) |

| Stepwise | PSA | (MCH × 0.673) - (MCV × 0.358) + (PLT × 0.014) + (RDW × 0.208) - 9.467 | 0.349 (< 0.0001) |

| Forward | PSA | (Age × 0.002) + (MCH × 0.710) - (WBC × 0.093) + (PLT × 0.015) + (RDW × 0.217) - (MCV × 0.366) + 7.667 | 0.54 (< 0.0001) |

| Backward | PSA | (MCH × 10.673) - (MCV × 0.358) + (PLT × 0.014) + (RDW × 0.208) - 9.467 | 0.51 (< 0.0001) |

| Orthoreg a | Prostate volume | (Age × 0.0743) + (WBC × 2.234) + (HCT × 1.456) + (MCH × 2.768) + (MCHC × 0.936) + (Nutr × 2.635) + (Lymph × 2.366) + (MXD × 3.312) + (RDW × 4.683) - (PLT × 0.003) - (MCV × 1.934) - (RBC × 22.564) - 183.935 | 0.25 (0.0025) |

| Orthoreg | PSA | (Age × 0.001) + (WBC × 00.5) + (RBC × 10.622) + (MCH × 1.579) + (MCHC × 0.533) + (PLT × 0.011) + (RDW × 0.169) - (MXD × 0.195) - (Lymph × 0.246) - (Nutr × 0.262) - (MCV × 0.212) - (Hb × 3.268) - 35.411 | 0.54 (< 0.0001) |

Abbreviations: WBC, white blood cell; RDW, red cell distribution width; PSA, prostate-specific antigen; MCV, mean corpuscular volume; MCHC, mean corpuscular hemoglobin concentration; RBC, red blood cell.

a This option of linear modeling is used for situations where the independent variables used have linear alignment.

The orthoreg modeling method is used to construct linear statistical models when the predictor variables exhibit high linear collinearity. This approach generates a model for estimating the target dependent variable by incorporatng all available predictor variables. The results presented in Table 5 indicate that the models developed using this method do not demonstrate a higher coefficient of determination for predicting prostate volume and PSA concentration.

5. Discussion

5.1. Correlation Between Prostate Volume and Prostate-Specific Antigen with Hematological Traits

This study examined relationships between prostate volume, serum PSA, and 12 hematological variables in BPH to develop predictive models for resource-limited settings. Mean prostate volume (82.66 mL) and PSA (3.76 ng/mL) at mean age 71.75 years were lower than expected, supporting the limited reliability of PSA in BPH diagnosis (10-12). Variance in variables suggests multifactorial influences (13). Covariance and regression analyses showed that prostate volume was correlated with age, RBC count, hemoglobin, hematocrit, neutrophil percentage, and RDW (P < 0.05). This is consistent with inflammatory processes involving neutrophils and blood changes (14). Unexpected RBC-related correlations align with studies showing lower hemoglobin and hematocrit in high-PSA groups (15) or treated PCa (16).

The PSA showed weaker correlations, significant only with MCV, platelet count, and RDW. Shared RDW correlations indicate links to anisocytosis. Biologically, MCV (reflecting RBC size) may correlate with PSA via chronic inflammation altering erythropoiesis and prostate epithelium; platelet count could relate to thrombocytosis in BPH inflammation, promoting PSA release through cytokine pathways. Pearson correlations were weak (absolute value less than 0.3), with the highest values for prostate volume-age (0.285) and PSA-MCV/platelet count (0.316/0.305), consistent with prior age-corrected correlations (17). Our negative RBC/hemoglobin correlations match Nigerian findings (15) and hormonal therapy studies (16), but discrepancies (e.g., lack of strong WBC-PSA link) may stem from population differences.

5.2. Linear Alignment Among Hematological Traits

Weak relationships may reflect collinearity (18-20). The lowest tolerance and highest VIF for neutrophil and lymphocyte percentages, RBC count, hemoglobin, and hematocrit indicate redundancy; age, WBC, platelet count, and RDW exhibited low collinearity, enhancing model utility.

5.3. Applied Linear Statistical Models

No viable prostate volume models were found (R2 less than 0.22); PSA models had higher R2 values (0.51 - 0.54), excluding age, with shared variables (RBC count, MCH, MCHC, platelet count, hemoglobin, RDW). Higher PSA model validity likely results from stronger correlations. Similar modeling approaches are used to estimate glomerular filtration rate or cancer outcomes (17, 21, 22).

5.4. Comparison with Emerging Biomarkers

While this study focuses on conventional biomarkers (PSA, hematological parameters) in BPH, prostate diseases, including cancer, also involve advanced biomarkers such as noncoding RNAs (ncRNAs). In cancers (e.g., lung, hepatocellular carcinoma, glioma), circular RNAs (circRNAs) regulate Wnt/β-catenin and PI3K/Akt pathways, influencing progression, apoptosis, and inflammation (23-34). Long ncRNAs in acute myeloid leukemia and bladder cancer modulate STAT3, apoptosis, and drug resistance (25, 27). MicroRNAs such as miR-489 suppress tumors via apoptosis induction and Wnt inhibition (24). These findings contrast with our routine CBC-based approach for BPH but highlight the potential for ncRNA integration in prognostic models assessing malignant transformation risk.

5.5. Clinical Applications and Limitations

The findings suggest that hematological parameters may be useful for PSA estimation in early diagnosis, patient stratification, or resource optimization in low-access settings. However, limitations include the retrospective design (potential bias), single-center data (limited generalizability), unmeasured confounders (e.g., comorbidities), and excluded cases due to incomplete records. Future research should validate these findings prospectively, explore additional parameters, or integrate ncRNAs for comprehensive models.

5.6. Conclusions

Linear regressions showed that prostate volume was associated with age, RBC count, hemoglobin, hematocrit, neutrophil percentage, and RDW; PSA was associated with MCV, platelet count, and RDW. Correlations were weak, with no strong phenotypic links. Hematological parameters failed to predict prostate volume (R2 less than 0.22) but showed promise for PSA (R2 = 0.52). These insights may aid diagnostic models, but claims are tempered by limitations such as retrospective bias and single-center scope, warranting cautious application.

5.7. Limitations

Main limitations include incomplete clinical/laboratory data leading to exclusions, retrospective design introducing selection bias, single-center scope limiting generalizability, and potential unmeasured confounders (e.g., diet, medications).